Sustainable Development Goal 6

Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6 or Global Goal 6) is about "clean water and sanitation for all". It is one of 17 Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, the official wording is: "Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all."[1] The goal has eight targets to be achieved by 2030. Progress toward the targets will be measured by using eleven indicators.[2]

| Sustainable Development Goal 6 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mission statement | "Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all" |

| Commercial? | No |

| Type of project | Non-Profit |

| Location | international |

| Owner | Supported by United Nations & Owned by the community |

| Founder | United Nations |

| Established | 2015 |

| Website | sdgs |

The six "outcome-oriented targets" include: Safe and affordable drinking water; end open defecation and provide access to sanitation, and hygiene, improve water quality, wastewater treatment and safe reuse, increase water-use efficiency and ensure freshwater supplies, implement IWRM, protect and restore water-related ecosystems. The two "means of achieving" targets are to expand water and sanitation support to developing countries, and to support local engagement in water and sanitation management.[3]

In 2017, 2.2 billion people lacked safely managed drinking water and 4.2 billion people lacked safely managed sanitation.[4] Three billion people worldwide lack basic hand-washing facilities at home.[4] Two in five healthcare facilities world-wide have no soap and water, or alcohol-based hand rub (2016).[4] The COVID-19 pandemic has made this goal increasingly important.[5] However this pandemic could affect the ability of water utilities to meet this goal by increasing losses on revenues that would otherwise be used to make investments.[6]

SDG 6 is closely linked with other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For example, progress in SDG 6 will improve health SDG3 and improve school attendance, both of which contribute to alleviating poverty. In April 2020, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said: “Today, Sustainable Development Goal 6 is badly off track" and it “is hindering progress on the 2030 Agenda, the realization of human rights and the achievement of peace and security around the world".[7]

Background

%252C_water_well_with_tree.jpg.webp)

The United Nations (UN) has determined that access to clean water and sanitation facilities is a basic human right.[8] However few countries have included a human right to water in enforceable legislation. Over 2 billion people in the world lack access to water that is free of health risks.[9] By 2017, eighty countries provided access to clean water for more than 99% of their population.[10] From 2000 to 2017, the global population that lacked access to clean water decreased from nearly 20% to roughly 10%.[9]

Ending open defecation will require the provision of toilets and sanitation for 2.6 billion people as well as behavior change of the population.[11] To meet SDG targets for sanitation by 2030, nearly one-third of countries will need to accelerate progress to end open defecation, including Brazil, China, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Pakistan.[12] This will require cooperation between governments, civil society and the private sector.[13]

Safe drinking water and hygienic toilets protect people from disease and enable societies to be more productive economically. Attending school and work without disruption supports education and employment. Therefore, toilets at school and the workplace are included in the second target ("achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all"). Equitable sanitation and hygiene solutions address the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations, such as the elderly or people with disabilities.

In June 2019, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization released their 138-page report "Progress on household drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene 2000-2017: special focus on inequalities."[9] The report said that in 2017, 5.3 billion people—representing 71% of the population of the world—used a "safely managed drinking-water service—one that is "located on premises, available when needed, and free from contamination".[9] By 2017, 6.8 billion people—representing 90% of the world's population—used "at least a basic service", which included "an improved drinking-water source within a round trip of 30 minutes to collect water".[9] However, in 2017, there were still 785 million people who lacked "even a basic drinking-water service, including 144 million people who [were] dependent on surface water."[9] The report said that approximately 2 billion people used a "drinking water source contaminated with feces".[9] The report warned that diseases, including "diarrhoea, cholera, dysentery, typhoid, and polio" are transmitted by contaminated water, which cause about 485, 000 diarrhoeal deaths each year.[9] It cautioned that 50% of the global population will be "living in water-stressed areas" by 2025.[9] As of 2017, 22% of health care facilities in the least developed countries had no water service, with similar numbers lacking sanitation and waste management services.[9]

A review of SDG progress by the UN in 2020 found that "increasing donor commitments to the water sector will remain crucial to make progress towards Goal 6".[5] This is why the UN has put in place a unifying initiative that improves support to countries known as SDG 6 Global Acceleration Framework.[14]

Targets, indicators and progress

SDG 6 has eight targets. Six of them are to be achieved by the year 2030, one by the year 2020, and one has no target year.[16] Each of the targets also has one or two indicators which will be used to measure progress. In total there are 11 indicators to monitor progress for SDG6.[17] The main data sources for the SDG 6 targets and indicators come from the Integrated Monitoring Initiative for SDG 6 coordinated by UN-Water.[18] Each government must decide how to incorporate them into national planning processes, policies and strategies based on national realities, capacities, levels of development and priorities.[18]

The six "outcome-oriented targets" include: Safe and affordable drinking water; end open defecation and provide access to sanitation, and hygiene, improve water quality, wastewater treatment and safe reuse, increase water-use efficiency and ensure freshwater supplies, implement IWRM, protect and restore water-related ecosystems. The two "means of achieving" targets are to expand water and sanitation support to developing countries, and to support local engagement in water and sanitation management.[3]

The first three targets relate to drinking water supply, sanitation services, and wastewater treatment and reuse.[16]

An SDG 6 Baseline Report in 2018 found that less than 50 percent of countries have comparable baseline estimates for most SDG 6 global indicators.[18]: 31 One reason is that many SDG 6 global indicators are new, and most have only limited time series, making it difficult to determine rates of progress.[18]: 31

Target 6.1: Safe and affordable drinking water

The full title of Target 6.1 is: "By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all".[2]

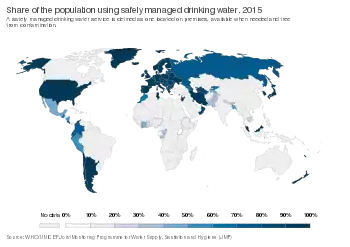

This target has one indicator: Indicator 6.1.1 is the "Proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services".[15]

The definition of "safely managed drinking water service" is: "Drinking water from an improved water source that is located on premises, available when needed and free from fecal and priority chemical contamination."[11]: 8 Between 2000 and 2015, the percentage of the global population using safely managed drinking water services has increased from 61 to 71 percent. But this remained unchanged in 2017. In total, 785 million people around the world still lacked basic drinking water services.[19]

In 2017, only 71 percent of the global population used safely managed drinking water. This means that 2.2 billion persons were still without safely managed drinking water in 2017.[5]

Compared to 2017, 74% of the world's population will have access to safely managed drinking water in 2020. This is an improvement over the past, but 2 billion people still do not have access to safely managed drinking water, especially in rural areas and the least developed countries. In 2020, 771 million people still lack access to even basic drinking water services. 8 out of 10 of these people live in rural areas, and nearly half live in the least developed countries; none of the SDG regions are currently expected to have universal coverage by 2030, and in sub-Saharan Africa, the number of people lacking access to safe managed drinking water has increased by more than 40% since 2000. At the current rate of progress, the global target of universal access to safely managed drinking water by 2030 would need to be quadrupled.[20]

Target 6.2: End open defecation and provide access to sanitation and hygiene

The full title of Target 6.2 is: "By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations."[2]

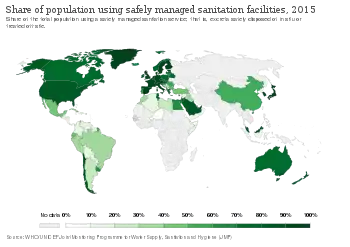

This target has one indicator: Indicator 6.2.1 is the "Proportion of population using (a) safely managed sanitation services and (b) a hand-washing facility with soap and water".[21]

The definition of "safely managed sanitation" service is: "Use of improved facilities that are not shared with other households and where excreta are safely disposed of in situ or transported and treated offsite."[11]: 8 Improved sanitation facilities are those designed to hygienically separate excreta from human contact.[11]: 6

Targets 6.1 and 6.2 are usually reported on together because they are both part of the WASH sector and have the same custodian agency, the Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP).[11]

The statistic in the 2017 baseline estimate by the Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP) is that 4.5 billion people currently do not have safely managed sanitation.[11]

.jpg.webp)

Globally, the proportion of the population using safely managed sanitation services increased from 28 percent in 2000 to 45 percent in 2017. Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, and East and Southeast Asia recorded the largest increase. In total, there are still 701 million people around the world who still had to practice open defecation in 2017.[19] This number had reduced in 2020 to 673 million persons who practised open defecation.[5]

As of 2017, two-thirds of countries lacked baseline estimates for SDG indicators on hand washing, safely managed drinking water, and sanitation services.[22]

In 2017, about 60 percent of people worldwide have basic hand-washing facilities with soap and water at home. However, within the least developed countries, only 38 percent had such facilities, translating to about 3 billion people still without basic handwashing facilities at home.[19]

In 2020, a report by the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development found that "Billions of people throughout the world still lack access to safely managed water and sanitation services and basic handwashing facilities at home, which are critical to preventing the spread of COVID-19".[5] However, this same pandemic has most likely caused a reduction in access to safely managed sanitation.[23]

Target 6.3: Improve water quality, wastewater treatment, and safe reuse

Target 6.3 is formulated as "By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally".[2] This is also a sanitation-related target, as wastewater treatment is part of sanitation.

The target has two indicators:[21]

- Indicator 6.3.1: Proportion of domestic and industrial wastewater flows safely treated

- Indicator 6.3.2: Proportion of bodies of water with good ambient water quality

The current status for Indicator 6.3.2 is that: "Preliminary estimates from 79 mostly high- and higher-middle income countries in 2019 suggest that, in about one quarter of the countries, less than half of all household wastewater flows were treated safely."[5]

Preserving natural sources of water is very important to achieve universal access to safe and affordable drinking water.

Target 6.4: Increase water-use efficiency and ensure freshwater supplies

Target 6.4 is formulated as "By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity."[2]

This target has two indicators:[21]

- Indicator 6.4.1: Change in water-use efficiency over time

- Indicator 6.4.2: Level of water stress: freshwater withdrawal as a proportion of available freshwater resources

The current situation regarding water stress was summarized as follows: "In 2017, Central and Southern Asia and Northern Africa registered very high water stress – defined as the ratio of freshwater withdrawn to total renewable freshwater resources – of more than 70 percent". This is followed by Western Asia and Eastern Asia, with high water stress of 54 percent and 46 percent, respectively.[5]

Target 6.5: Implement IWRM

Target 6.5 is formulated as: "By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate."[2]

The two indicators include:[21]

- Indicator 6.5.1 Degree of integrated water resources management

- Indicator 6.5.2 Proportion of transboundary basin area with an operational arrangement for water cooperation

A review in 2020 stated that: "In 2018, 60 percent of 172 countries reported very low, low and medium-low levels of implementation of integrated water resources management and were unlikely to meet the implementation target by 2030."[5]

The same review stated that: "According to data from 67 countries, the average percentage of national transboundary basins covered by an operational arrangement was 59 percent in the period 2017–2018. Only 17 countries reported that all of their transboundary basins were covered by such arrangements."[5]

Target 6.6: Protect and restore water-related ecosystems

Target 6.6 is: "By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes."[2]

It has one indicator: Indicator 6.6.1 is the "Change in the extent of water-related ecosystems over time".[21]

It is expected that the adverse effects of climate change can decrease the extent of freshwater bodies, thereby worsening ecosystems and livelihoods.[5]

Target 6.a: Expand water and sanitation support to developing countries

Target 6.a is: "By 2030, expand international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries in water- and sanitation-related activities and programmes, including water harvesting, desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling, and reuse technologies."[2]

It has one indicator: Indicator 6.a.1 is the "Amount of water- and sanitation-related official development assistance that is part of a government-coordinated spending plan".[21]

In 2015, global ODA allocations to the water sector totalled us $8.6 billion, including ensuring basic water supply and sanitation, and improving agricultural water resources and hydropower. However,80% of countries fail to meet water and sanitation targets because of insufficient funding [6].

SDG 6 is not going well because of poor policy implementation, staff shortages, inadequate funding, and the limited impact of aid money when consistent long-term investments are not put into place.[24] Technological innovation and more effective management are the foundations for advancing SDG 6 in the context of aid funding shortfalls.Therefore, reducing capital expenditure can save a lot of costs. For rural areas in developing countries, it is necessary to use appropriate materials, optimize procurement and eliminate middlemen[7].

In 2019, a document by the UN found that: "Following several years of steady increases and after reaching $9 billion in 2016, official development assistance (ODA) disbursements to the water sector declined by 2 percent from 2016 to 2017. However, ODA commitments to the water sector jumped by 36 percent between 2016 and 2017, indicating a renewed focus by donors on the sector."[25]

One year later in April 2020 it was stated that "ODA disbursements to the water sector increased to $9 billion, or 6 per cent, in 2018, following a decrease in such disbursements in 2017".[5]

Over 2 billion people lack properly managed drinking water. An additional 1.6 billion are subjects of poor sanitation. If the status quo persists, the world will not have enough water to meet demand by 2030 hence making it impossible to meet SDG 6- safe drinking water and sanitation for all. Climate change is also making the situation of water availability worse as it negatively impacts on world water systems through increased incidents of drought, floods, and rainfall unreliability. To overcome the problem of water crisis, the Global Water Security & Sanitation Partnership (GWSP) collaborates with several countries to make water available to its citizen. In 2020, GWSP collaborated with the Dominican Republic in the province of Espaillat to renovate and adopt innovative ways of water collection and treatment where the water treatment system has been dysfunctional since 2004. This has improved sanitation, hygiene, and availability of clean drinking water.

Target 6.b: Support local engagement in water and sanitation management

Target 6.b is: "Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management."[2]

It has one indicator: Indicator 6.b.1 is the "Proportion of local administrative units with established and operational policies and procedures for participation of local communities in water and sanitation management".[21]

Custodian agencies

Custodian agencies are in charge of reporting on the following indicators:[11][18]

- Indicator 6.1.1 and 6.2.1: Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP). The JMP is a joint program of UNICEF and WHO and compiles data to monitor the progress of Target 6.1 and Target 6.2.

- Indicator 6.3.1: UN-Habitat and WHO

- Indicator 6.3.2: Global Environment Monitoring System for Freshwater (GEMS/Water), International Centre for Water Resources and Global Change (UNESCO-IHP); Federal Institute of Hydrology, Germany; University College Cork, Ireland

- Indicators 6.4.1 and 6.4.2: FAOSTAT - AQUASTAT

- Indicator 6.5.1: United Nations Environment Programme-DHI Centre

- Indicator 6.5.2: UNECE and UNESCO-IHP

- Indicator 6.6.1: United Nations Environment Programme, World Conservation Monitoring Centre, International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

- Indicators 6.a.1 and 6.b.1: UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS)

Challenges

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly affected the urban poor living in the slums with little or no access to clean water.[26] [27]The pandemic has shown the importance of sanitation, hygiene and adequate access to clean water to prevent diseases. According to the World Health Organization, handwashing is one of the most effective actions one can take to reduce the spread of pathogens and prevent infections, including the COVID-19 virus.[28]

The world is being asked to wash hands multiple times in a day, wash and sanitize every object brought from outside, and sanitize all public transport at a certain interval in a day.[29] The water consumption, as well as the wastewater generation all across the globe, has now increased manifold. The UN-Habitat is working with partners to facilitate access to running water and hand washing in informal settlements.[28] With the increased exploitation of water resources in 2020 its reported that by 2030 700 million people might be displaced by water scarcity.[30]

Supply and demand-sided challenges

Clean water and sanitation are not only affected by macro-environmental trends but they are also affected by large-scale industrial targets and water consumption habits.[31] As developing nations in Sub-Saharan Africa and South-South-East Asia become more affluent, these countries have unique challenges to recycle and protect water ecosystems. At the establishment of Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, the previous MDGs had left 663 million needing improved water access.[32]

In 2019, GLAAS report (UN-Water Global Analysis And Assessment Of Sanitation And Drinking-Water) found that only 6 of 101 countries were fully equipped with financial and human resources to tackle cleaning and sanitizing water supplies within their own countries.[33] Less than 15% of countries are adequately meeting the goal of properly funding clean water and sanitation efforts within their own countries. This funding shortfall affects other areas relating to SDG 6 and its progress indicators. For example, while clean drinking water efforts have been funded relatively well, sanitation, waste-water management, and hygiene areas have stalled in their progress towards 2030.[34]

Much of the focus in the next decade is on Sub-Saharan African countries that will likely not meet their targets if growing funding is not secure within the next decade. For example in two countries in North-Eastern Africa where utilities taxes are higher than their surrounding regions, public utilities are still not able to keep up with the regular demand for water.[35] In further complicating the issue, multi-level governance remains an important factor in efficiently directing funds to where they are needed. Sustainable water management practices are only possible if there is a local solution for Sub-Saharan Africa that integrates existing water management techniques and practices.[36]

Monitoring

High-level progress reports for all the SDGs are published in the form of reports by the United Nations Secretary General. The most recent one is from April 2020.[5] The report before that was from May 2019.[25]

Additionally, updates and progress can also be found on the SDG website which is managed by the United Nations.[4]

Monitoring national-level progress of SDG 6 through internationally agreed indicators has been the focus of intense scrutiny and considerable resourcing by international organizations and national governments. Indicators for SDG 6 are monitored and reported on at an international level by United Nations (UN) custodian agencies under the UN-Water managed Integrated Monitoring Initiative for SDG 6 (IMI), although national data and results will form the basis of all monitoring and reporting.[37]

In many cases, surrogate indicators will have to be used to measure progress (or the lack of it). Thus, implementation of the SDGs implies continuous monitoring and periodic evaluation to check whether the direction and pace of development are right.[38] Robust indicators will do two things: enable the SDG targets to act as a management tool to help countries and the global community create evidence-based implementation strategies and allocate resources accordingly; and act as a report card to measure SDG progress.[37]

Links with other SDGs

The SDGs are highly interdependent. Therefore, the provision of clean water and sanitation for all is a precursor to achieving many of the other SDGs.[39] WASH experts have stated that without progress on Goal 6, the other goals and targets cannot be achieved.[40][41]

For example, sanitation improvements can lead to more jobs (SDG 8) which would also lead to economic growth.[42] SDG 6 progress improves health (SDG 3) and social justice (SDG 16).[43] Recovering the resources embedded in excreta and wastewater (like nutrients, water, and energy) contributes to achieving SDG 12 (sustainable consumption and production) and SDG 2 (end hunger). Ensuring adequate sanitation and wastewater management along the entire value chain in cities contributes to SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) and SDG 1 (no poverty).[42]

Sanitation systems with a resource recovery and reuse focus are getting increased attention.[44] They can contribute to achieving at least fourteen of the SDGs, especially in an urban context.[42]

Organizations

The Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA) has made it its mission to help achieve Targets 6.2 and 6.3.[45][46] Global organizations such as Oxfam, UNICEF, WaterAid and many small NGOs as well as universities, research centers, private enterprises, government-owned entities etc. are all part of SuSanA and are dedicated to achieving SDG 6.[47]

US Based Organizations

In the US there are over three thousand tax-exempt organizations working on issues related to UN SDG 6, according to data filed with the Internal Revenue Service –IRS and aggregated by X4Impact.[48] X4Impact, with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, Ford Foundation,[49] Hewlett Foundation,[50] and Giving Tech Labs, created a free online interactive tool Clean Water and Sanitation in the US.[51]

SDG 6 in a Canadian Context

The United Nations has listed Sustainable Development (SDG) Goal 6 as the aim to “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all people (United Nations, 2022). I am specifically going to discuss this goal in a Canadian context as this information has not been acknowledged in Wikipedia’s literature on this topic. The the aim of the Canadian goal has been described as “Canadians have access to drinking water and use it in a sustainable manner” (Statistics Canada, 2021), below are the current indicators of what needs to be achieved to reach this goal:

“Indicator 6.1.1 states:

Target

All of the long-term drinking water advisories on public systems on reserve are to be resolved

Indicator

Number of long-term drinking water advisories on public systems on reserves

6.2.1

Target

No specific target

Indicator

Percentage of municipalities across Canada with sustained drinking water advisories

6.3.1

Target

No specific target

Indicator

Water use growth rate

6.4.1

Target

No specific target

Indicator

Water quality in Canadian rivers” (Statistics Canada, 2021).

I will be explicitly writing about Indicator 6.1.1, given the lack of meaningful action that has been taken towards the ongoing issues of water quality and adequate sanitation measures on Indigenous reserves in Canada. This part of the Canadian SDG has yet to be achieved, and the progress towards meeting this goal has been minimal thus far. It has been reported that in 2021 almost half of the drinking water advisories on Indigenous reservations were lifted, yet 7 more were added during the same time span (Statistics Canada, 2022 ). In 2022, Indigenous Services Canada stated that there are at least 29 communities in Canada with boil water advisories in effect (Richardson, 2022). This is significant to the discussion around SDGs in Canada, because ultimately the overall goal of clean water and sanitation access for all Canadians as long as there are disparities in Indigenous communities around water quality and sanitation measures.

The definition of water security has expanded in recent literature to encompass:

water quality, human health, water-related hazards, sustainable development, water supply, and ecological concerns…, involves a balance between the protection of resources and the enhancement of livelihoods, Determinants of water security include water availability for ecosystem services as well as acceptable quality and quantity for human uses. Water security is presented in the literature as meeting short and long-term needs to enable access to sufficient water quality, at a fair price, for human health, safety, welfare, and productive capacity…linked to the political, social, and economic power of people in society… (Indigenous perspectives on water security, pg. 1).

Although Canada, like many high-income countries, have made advancements in providing accessible safe water and sanitation measures, significant gaps in terms of access and quality of these necessities persist in “...historically marginalized, rural, informal, and Indigenous communities” (Mattos et. al, 2021, pg. 1). Such disparities are prevalent in Indigenous communities in Canada, even though the country’s government has signed on to the UN’s sustainable development goals (Mattos et. al, 2021, pg. 2). Notably, a “… lack of community water distribution systems, inadequate technology, lack of federal funding, and land use activities that affect source water quality” all contribute to one in five Indigenous communities on reservations being under a boil water advisory at a time (Awume et. al, 2020,, pg. 1-2). These social inequities have resulted in disproportionate rankings of quality of life between Indigenous communities and the rest of Canada, whereby Canada has been one of the “...top placement in the UN Human Development Index, yet Canadian Indigenous peoples rank 78th on the same scale” (Asiniwasis, 2021, pg 188).

Disparities in Indigenous Communities Resulting in Minimal Progress

It is crucial to understand the historical and ongoing water crisis among Indigenous communities in Canada, along with how and why SDG Goal 6 has had minimal progress in these communities since Canada has signed onto the goal of achieving clean water and sanitation for all Canadians.

Numerous barriers and challenges from multiple levels of government have contributed to the existing disparities between Indigenous communities and the rest of Canada. Some specific issues cited in recent literature “...include lack of local capacity, inadequate funding, justice and discrimination issues, cultural obstacles, and specific technical challenges…[and] environmental injustice and racial discrimination” (Mattos et. al, 2021, pg. 4, 6), along with “ … inequitable resource distribution, sociopolitical and governance challenges…” (Arsenault et. al, 2018, pg. 2). Ultimately, these obstacles can all be linked to the historical and ongoing impacts from colonialism in Canada, which have expropriated land ownership and decision making abilities towards issues of water, sanitation, and health from the Indigenous communities who are directly impacted from these inequities (Mattos et. al, 2021, pg. 6). A significant issue in government jurisdiction lies within the fact that the Canadian government is “highly fragmented”, meaning that “… federal or provincial governance bodies have delegated water management responsibility to communities…” (Arsenault et. al, 2018, pg. 2); Specifically, the responsibility around water governance in Indigenous communities has been divided among “...Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, Health Canada, Environment Canada and First Nations community leadership…” and has caused severe difficulties around accountability measures (Arsenault et. al, 2018, pg. 5). Given that the Canadian 2030 Agenda states that “All federal departments and agencies are responsible for integrating the 2030 Agenda into their work. They are also responsible for contributing to advancing the SDGs within their areas of responsibility” (Government of Canada, 2021, pg. 3). Evidently, such issues of accountability for action will hinder the level of progress and development that can be made towards achieving water quality and sanitation measures on Indigenous reservations.

Recommendations to Achieving SDG 6 in Canada

In the emerging literature on Indigenous water quality, sanitation, and overall health, several recommendations to current measures toward improving the quality and access to these needs have been discussed, and should be taken into account and applied in all future action towards achieving SDG 6 in Canada. First and foremost, it is absolutely necessary that treaties made between all Indigenous communities in Canada and the Canadian government are recognized and fulfilled in their entirety (Mattos et. al, 2021, pg. 7). This will ensure that all discriminatory actions that have prevented social change from occurring in regards to water security and sanitation are abolished and transformative change to these conditions can be pursued (Mattos et. al, 2021, pg. 6). This means that “racist, nationalist, and colonial policies must be terminated and replaced with equitable legislation and regulations to protect and improve access for historically marginalized communities” (Mattos et. al, 2021, pg. 6). It is essential that the definition of water security is expanded in Western science and education to include Indigenous knowledge in water management and planning as Indigenous understanding of “...water security encapsulates a meaning that transcends the material definition offered by conventional, western science” (Awume et. al, 2021, pg. 10); “An “Indigenous perspective” introduces human values and relationships to water that includes respect for water and ethical decisions about water” (Awume et. al, 2021, pg. 7).

In order to do so, stakeholders concerned with water access and sanitation must work towards building reciprocal relationships between government bodies and Indigenous communities that respects traditional land ownership and Indigenous governance over their own environmental practices and health (Duignan et. al, 2022, pg. 7-8). Practical means of reciprocity in future research and development around water security includes developing “…exposure models and risk management strategies that are more reflective of the population’s social and cultural practices” (Daley et. al, 2022, pg. 2). Given that women hold a vital role in the leadership of Indigenous communities, women need to be at the forefront of all decision making and research processes for achieving water security (Duignan et. al, 2022, pg. 8). This goal will be best fulfilled by supporting Indigenous communities to achieve self determination, which can be achieved by assisting in the development of community based leadership programs and focusing on opportunities that give Indigenous communities control over their land, health, communities, and the environment (Mattos et. al, 2021 pg. 7).

References:

Arsenault, R., Diver, S., McGregor, D., Witham, A., & Bourassa, C. (2018). Shifting the framework of Canadian water governance through Indigenous research methods: Acknowledging the past with an eye on the future. Water, 10(1), 1-18. doi:10.3390/w10010049

Asiniwasis, R. N., Heck, E., Amir Ali, A., Ogunyemi, B., & Hardin, J. (2021). Atopic dermatitis and skin infections are a poorly documented crisis in Canada's Indigenous pediatric population: It's time to start the conversation. Pediatric Dermatology, 38(S2), 188-189. doi:10.1111/pde.14759

Awume, O., Patrick, R., & Baijius, W. (2020). Indigenous perspectives on water security in Saskatchewan, Canada. Water, 12(3), 1-14. doi:10.3390/w12030810

Daley, K., Jamieson, R., Rainham, D., Hansen, L. T., & Harper, S. L. (2022). Microbial risk assessment and mitigation options for wastewater treatment in Arctic Canada. Microbial Risk Analysis, 20, 1-14. doi:10.1016/j.mran.2021.100186

Duignan, S., Moffat, T., & Martin-Hill, D. (2022). Be like the running water: Assessing gendered and age-based water insecurity experiences with Six Nations First Nation. Social Science & Medicine, 298, 1-9. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114864

Government of Canada. (2021). Canada’s Federal Implementation Plan for the 2030 Agenda. Retrieved from Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada website: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/esdc-edsc/documents/programs/agenda-2030/Implementation-Plan_layout_EN_Web.pdf

Mattos, K. J., Mulhern, R., Naughton, C. C., Anthonj, C., Brown, J., Brocklehurst, C., … Smith, A. (2021). Reaching those left behind: Knowledge gaps, challenges, and approaches to achieving SDG 6 in high-income countries. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 11(5), 849-858. doi:10.2166/washdev.2021.057

Richardson, L. (2022, March 7). Process to apply for First Nations drinking water compensation now open. Retrieved from https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/process-to-apply-for-first-nations-drinking-water-compensation-now-open/

Statistics Canada. (2021, June 22). The Canadian indicator framework for the sustainable development goals. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-26-0004/112600042021001-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2022, September 28). Sustainable development goals: Goal 6, clean water and sanitation. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-637-x/2022001/article/00006-eng.htm

United Nations. (2022). Goal 6 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved from https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal6

References

- "Goal 6: Clean water and sanitation". UNDP. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- United Nations (2018). Sustainable Development Goal. 6, Synthesis report 2018 on water and sanitation. United Nations, New York. ISBN 9789211013702. OCLC 1107804829.

- "Goal 6 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". sdgs.un.org. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council (2020) Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals Report of the Secretary-General, High-level political forum on sustainable development, convened under the auspices of the Economic and Social Council (E/2020/57), 28 April 2020

- "The impact of covid 19 on water and sanitation".

- Blazhevska, Vesna (11 July 2020). "United Nations launches framework to speed up progress on water and sanitation goal". United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- "World Water Development Report 2019 - Leaving No One Behind". UNESCO. 2019-02-11. Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2017: Special focus on inequalities (PDF). United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization (Report). New York. June 2019. p. 138. ISBN 978-92-415-1623-5. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- Progress on sanitation and drinking-water: 2014 update. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization. 28 July 2014. ISBN 9789240692817. OCLC 889699199.

- WHO and UNICEF (2017) Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2017

- "Progress for Every Child in the SDG Era" (PDF). UNICEF. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Kellogg, Diane M. (2017). "The Global Sanitation Crisis: A Role for Business". Beyond the bottom line: integrating sustainability into business and management practice. Gudić, Milenko,, Tan, Tay Keong,, Flynn, Patricia M. Saltaire, UK: Greenleaf Publishing. ISBN 9781783533275. OCLC 982187046.

- "SDG6 action space".

- Ritchie, Roser, Mispy, Ortiz-Ospina (2018) "Measuring progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals." (SDG 6) SDG-Tracker.org, website

- "Goal 6 Targets". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "SDGs". Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- United Nations (2018). Sustainable Development Goal. 6, Synthesis report 2018 on water and sanitation. United Nations, New York. ISBN 9789211013702. OCLC 1107804829.

- "Special edition: progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Report of the Secretary-General". undocs.org. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- "Summary Progress Update 2021: SDG 6 — water and sanitation for all". UN-Water. Retrieved 2021-12-18.

- United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- "Progress for Every Child in the SDG Era" (PDF). UNICEF. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- BMGF (2020) Covid-19 A Global Perspective - 2020 Goalkeepers Report, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, USA

- Abellán, Javier; Alonso, José Antonio (2022). "Promoting global access to water and sanitation: A supply and demand perspective". Water Resources and Economics. 38: 100194. doi:10.1016/j.wre.2022.100194. S2CID 246261266.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council (2019) Special edition: progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, Report of the Secretary-General (E/2019/68), High-level political forum on sustainable development, convened under the auspices of the Economic and Social Council (8 May 2019)

- Heidari, Hadi; Grigg, Neil (2021). "Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Urban Water Cycle". Advances in Environmental and Engineering Research. 2 (3): 1. doi:10.21926/aeer.2103021.

- Staddon, C.; Everard, M.; Mytton, J.; Octavianti, T.; Powell, W.; Quinn, N.; Uddin, S. M. N.; Young, S. L.; Miller, J. D.; Budds, J.; Geere, J.; Meehan, K.; Charles, K.; Stevenson, E. G. J.; Vonk, J.; Mizniak, J. (3 July 2020). "Water insecurity compounds the global coronavirus crisis". Water International. 45 (5): 416–422. doi:10.1080/02508060.2020.1769345. S2CID 221106003.

- Martin. "Water and Sanitation". United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- "Impact of Covid-19 on SDG Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation". Times of India Blog. 2020-06-08. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- "The sustainable development goals report 2020" (PDF).

- Bo, Yan; Zhou, Feng; Zhao, Jianshi; Liu, Junguo; Liu, Jiahong; Cais, Phillipe; Chang, Jinfeng; Chen, Lei (2021). "Additional surface-water deficit to meet global universal water accessibility by 2030". Journal of Cleaner Production. 320 (3): 128829. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128829.

- Labat, Ashley (2018). "Measuring Progressive Realization of Sustainable Development Goal 6 A Review of Implementation Outcomes for Improvement". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 1 (1): 29. doi:10.17615/tmpr-5f64.

- World Health Organization (2019). "UN-Water GLAAS 2019: National systems to support drinking-water, sanitation and hygiene – Global status report 2019". UN Water. 1 (1): 144.

- Cai, Jialiang; Zhao, Dandan; Varis, Olli (2021). "Match words with deeds: Curbing water risk with the Sustainable Development Goal 6 index". Journal of Cleaner Production. 318 (4): 14. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128509.

- Libey, Anna; Adank, Marieke; Thomas, Evan (2020). "Who pays for water? Comparing life cycle costs of water services among several low, medium, and high-income utilities". World Development. 136: 13. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105155.

- Nkiaka, Elias; Bryant, Robert; Okumah, Murat; Gomo, Fortune Faith (2021). "Water security in sub-Saharan Africa: Understanding the status of sustainable development goal 6". WIREs Water. 8 (6): 13. doi:10.1002/wat2.1552.

- Guppy, Lisa; Mehta, Praem; Qadir, Manzoor (2019). "Sustainable development goal 6: two gaps in the race for indicators". Sustainability Science. 14 (2): 501–513. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0649-z. ISSN 1862-4057. S2CID 159237191.

- Bhaduri, Anik; Bogardi, Janos; Siddiqi, Afreen; Voigt, Holm; Vörösmarty, Charles; Pahl-Wostl, Claudia; Bunn, Stuart E.; Shrivastava, Paul; Lawford, Richard; Foster, Stephen; Kremer, Hartwig (2016). "Achieving Sustainable Development Goals from a Water Perspective". Frontiers in Environmental Science. 4: 64. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2016.00064. ISSN 2296-665X.

- "Sustainable sanitation and the SDGs: interlinkages and opportunities". Sustainable Sanitation Alliance Knowledge Hub. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Rao Gupta, Geeta (October 2015). "Opinion: "Sanitation, Water & Hygiene For All" Cannot Wait for 2030". Inter Press. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Batty, Margaret (25 September 2015). "Beyond the SDGs: How to deliver water and sanitation to everyone, everywhere". Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Andersson, Kim; Dickin, Sarah; Rosemarin, Arno (2016-12-08). "Towards "Sustainable" Sanitation: Challenges and Opportunities in Urban Areas". Sustainability. 8 (12): 1289. doi:10.3390/su8121289.

- "Press release – UN General Assembly's Open Working Group proposes sustainable development goals" (PDF). Sustainabledevelopment.un.org. 19 July 2014. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- Paranipe, Nitin (14 November 2017). "The rise of the sanitation economy: how business can help solve a global crisis". Thomson Reuters Foundation News. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- "Vision". Sustainable Sanitation Alliance. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Contribution of sustainable sanitation to the Agenda 2030 for sustainable development - SuSanA Vision Document 2017". SuSanA, Eschborn, Germany. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-11-16.

- "Contribution of sustainable sanitation to the Agenda 2030 for sustainable development - SuSanA Vision Document 2017". SuSanA, Eschborn, Germany. 2017.

- "Press Release: X4Impact, a Market Intelligence Platform for Social Innovation, Announced U.S. Launch During the 2020 Un General Assembly - NextBillion". nextbillion.net. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- X4Impact. "Ford Foundation Fuels Tech for the Public Interest with X4Impact". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- "Press Release: Hewlett Foundation Becomes X4Impact Founding Partner to Advance Technology for the Public Interest With Focus on Entrepreneurs Creating Tech for Good Solutions - NextBillion". nextbillion.net. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- "X4Impact - X4i.org - Clean Water and Sanitation in the US - Report". X4impact. Retrieved 2022-05-09.