Syncytium

A syncytium or symplasm (/sɪnˈsɪʃiəm/; plural syncytia; from Greek: σύν syn "together" and κύτος kytos "box, i.e. cell") is a multinucleate cell which can result from multiple cell fusions of uninuclear cells (i.e., cells with a single nucleus), in contrast to a coenocyte, which can result from multiple nuclear divisions without accompanying cytokinesis.[1] The muscle cell that makes up animal skeletal muscle is a classic example of a syncytium cell. The term may also refer to cells interconnected by specialized membranes with gap junctions, as seen in the heart muscle cells and certain smooth muscle cells, which are synchronized electrically in an action potential.

The field of embryogenesis uses the word syncytium to refer to the coenocytic blastoderm embryos of invertebrates, such as Drosophila melanogaster.[2]

Physiological examples

Protists

In protists, syncytia can be found in some rhizarians (e.g., chlorarachniophytes, plasmodiophorids, haplosporidians) and acellular slime moulds, dictyostelids (amoebozoans), acrasids (Excavata) and Haplozoon.

Plants

Some examples of plant syncytia, which result during plant development, include:

Fungi

A syncytium is the normal cell structure for many fungi. Most fungi of Basidiomycota exist as a dikaryon in which thread-like cells of the mycelium are partially partitioned into segments each containing two differing nuclei, called a heterokaryon.

Skeletal muscle

A classic example of a syncytium is the formation of skeletal muscle. Large skeletal muscle fibers form by the fusion of thousands of individual muscle cells. The multinucleated arrangement is important in pathologic states such as myopathy, where focal necrosis (death) of a portion of a skeletal muscle fiber does not result in necrosis of the adjacent sections of that same skeletal muscle fiber, because those adjacent sections have their own nuclear material. Thus, myopathy is usually associated with such "segmental necrosis", with some of the surviving segments being functionally cut off from their nerve supply via loss of continuity with the neuromuscular junction.

Cardiac muscle

The syncytium of cardiac muscle is important because it allows rapid coordinated contraction of muscles along their entire length. Cardiac action potentials propagate along the surface of the muscle fiber from the point of synaptic contact through intercalated discs. Although a syncytium, cardiac muscle differs because the cells are not long and multinucleated. Cardiac tissue is therefore described as a functional syncytium, as opposed to the true syncytium of skeletal muscle.

Smooth muscle

Smooth muscle in the gastrointestinal tract is activated by a composite of three types of cells – smooth muscle cells (SMCs), interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs), and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα) that are electrically coupled and work together as an SIP functional syncytium.[6][7]

Osteoclasts

Certain animal immune-derived cells may form aggregate cells, such as the osteoclast cells responsible for bone resorption.

Placenta

Another important vertebrate syncytium is in the placenta of placental mammals. Embryo-derived cells that form the interface with the maternal blood stream fuse together to form a multinucleated barrier – the syncytiotrophoblast. This is probably important to limit the exchange of migratory cells between the developing embryo and the body of the mother, as some blood cells are specialized to be able to insert themselves between adjacent epithelial cells. The syncytial epithelium of the placenta does not provide such an access path from the maternal circulation into the embryo.

Glass sponges

Much of the body of Hexactinellid sponges is composed of syncitial tissue. This allows them to form their large siliceous spicules exclusively inside their cells.[8]

Tegument

The fine structure of the tegument in helminths is essentially the same in both the cestodes and trematodes. A typical tegument is 7–16 μm thick, with distinct layers. It is a syncytium consisting of multinucleated tissues with no distinct cell boundaries. The outer zone of the syncytium, called the "distal cytoplasm," is lined with a plasma membrane. This plasma membrane is in turn associated with a layer of carbohydrate-containing macromolecules known as the glycocalyx, that varies in thickness from one species to another. The distal cytoplasm is connected to the inner layer called the "proximal cytoplasm", which is the "cellular region or cyton or perikarya" through cytoplasmic tubes that are composed of microtubules. The proximal cytoplasm contains nuclei, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi complex, mitochondria, ribosomes, glycogen deposits, and numerous vesicles.[9] The innermost layer is bounded by a layer of connective tissue known as the "basal lamina". The basal lamina is followed by a thick layer of muscle.[10]

Pathological examples

Viral infection

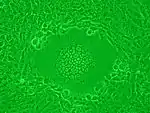

Syncytia can also form when cells are infected with certain types of viruses, notably HSV-1, HIV, MeV, SARS-CoV-2, and pneumoviruses, e.g. respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). These syncytial formations create distinctive cytopathic effects when seen in permissive cells. Because many cells fuse together, syncytia are also known as multinucleated cells, giant cells, or polykaryocytes.[11] During infection, viral fusion proteins used by the virus to enter the cell are transported to the cell surface, where they can cause the host cell membrane to fuse with neighboring cells.

Reoviridae

Typically, the viral families that can cause syncytia are enveloped, because viral envelope proteins on the surface of the host cell are needed to fuse with other cells.[12] Certain members of the Reoviridae family are notable exceptions due to a unique set of proteins known as fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) proteins.[13] Reovirus induced syncytium formation is not found in humans, but is found in a number of other species and is caused by fusogenic orthoreoviruses. These fusogenic orthoreoviruses include reptilian orthoreovirus, avian orthoreovirus, Nelson Bay orthoreovirus, and baboon orthoreovirus.[14]

HIV

HIV infects Helper CD4+ T cells and makes them produce viral proteins, including fusion proteins. Then, the cells begin to display surface HIV glycoproteins, which are antigenic. Normally, a cytotoxic T cell will immediately come to "inject" lymphotoxins, such as perforin or granzyme, that will kill the infected T helper cell. However, if T helper cells are nearby, the gp41 HIV receptors displayed on the surface of the T helper cell will bind to other similar lymphocytes.[15] This makes dozens of T helper cells fuse cell membranes into a giant, nonfunctional syncytium, which allows the HIV virion to kill many T helper cells by infecting only one. It is associated with a faster progression of the disease[16]

Mumps

The mumps virus uses HN protein to stick to a potential host cell, then, the fusion protein allows it to bind with the host cell. The HN and fusion proteins are then left on the host cell walls, causing it to bind with neighbour epithelial cells.[17]

COVID-19

Mutations within SARS-CoV-2 variants contain spike protein variants that can enhance syncytia formation.[18] The protease TMPRSS2 is essential for syncytia formation.[19] Syncytia can allow the virus to spread directly to other cells, shielded from neutralizing antibodies and other immune system components.[18] Syncytia formation in cells can be pathological to tissues.[18]

"Severe cases of COVID-19 are associated with extensive lung damage and the presence of infected multinucleated syncytial pneumocytes. The viral and cellular mechanisms regulating the formation of these syncytia are not well understood,"[20] but membrane cholesterol seems necessary.[21][22]

The syncytia appear to be long-lasting; the "complete regeneration" of the lungs after severe flu "does not happen" with COVID-19.[23]

See also

- Atrial syncytium

- Coenocyte

- Giant cell

- Heterokaryon

- Heterokaryosis

- Plasmodium (life cycle)

- Enteridium lycoperdon, a plasmodial slime mould

- Syncytiotrophoblast

- Xenophyophorea

References

- Daubenmire, R. F. (1936). "The Use of the Terms Coenocyte and Syncytium in Biology". Science. 84 (2189): 533–534. Bibcode:1936Sci....84..533D. doi:10.1126/science.84.2189.533. PMID 17806555.

- Willmer, P. G. (1990). Invertebrate Relationships: Patterns in Animal Evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Płachno, B. J.; Swiątek, P. (2010). "Syncytia in plants: Cell fusion in endosperm—placental syncytium formation in Utricularia (Lentibulariaceae)". Protoplasma. 248 (2): 425–435. doi:10.1007/s00709-010-0173-1. PMID 20567861. S2CID 55445.

- Tiwari, S. C.; Gunning, B. E. S. (1986). "Colchicine inhibits plasmodium formation and disrupts pathways of sporopollenin secretion in the anther tapetum ofTradescantia virginiana L". Protoplasma. 133 (2–3): 115. doi:10.1007/BF01304627. S2CID 24345281.

- Murguía-Sánchez, G. (2002). "Embryo sac development in Vanroyenella plumosa, Podostemaceae". Aquatic Botany. 73 (3): 201–210. doi:10.1016/S0304-3770(02)00025-6.

- Song, NN; Xu, WX (2016-10-25). "[Physiological and pathophysiological meanings of gastrointestinal smooth muscle motor unit SIP syncytium]". Sheng li xue bao: [Acta Physiologica Sinica]. 68 (5): 621–627. PMID 27778026.

- Sanders, KM; Ward, SM; Koh, SD (July 2014). "Interstitial cells: regulators of smooth muscle function". Physiological Reviews. 94 (3): 859–907. doi:10.1152/physrev.00037.2013. PMC 4152167. PMID 24987007.

- "Palaeos Metazoa: Porifera:Hexactinellida".

- Gobert, Geoffrey N.; Stenzel, Deborah J.; McManus, Donald P.; Jones, Malcolm K. (December 2003). "The ultrastructural architecture of the adult Schistosoma japonicum tegument". International Journal for Parasitology. 33 (14): 1561–1575. doi:10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00255-8. ISSN 0020-7519. PMID 14636672.

- Jerome), Bogitsh, Burton J. (Burton (2005). Human parasitology. Carter, Clint E. (Clint Earl), Oeltmann, Thomas N. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 0120884682. OCLC 769187741.

- Albrecht, Thomas; Fons, Michael; Boldogh, Istvan; Rabson, Alan S. (1996-01-01). Baron, Samuel (ed.). Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 0963117211. PMID 21413282.

- "ViralZone: Syncytium formation is induced by viral infection". viralzone.expasy.org. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- Salsman, Jayme; Top, Deniz; Boutilier, Julie; Duncan, Roy (2005-07-01). "Extensive Syncytium Formation Mediated by the Reovirus FAST Proteins Triggers Apoptosis-Induced Membrane Instability". Journal of Virology. 79 (13): 8090–8100. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.13.8090-8100.2005. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 1143762. PMID 15956554.

- Duncan, Roy; Corcoran, Jennifer; Shou, Jingyun; Stoltz, Don (2004-02-05). "Reptilian reovirus: a new fusogenic orthoreovirus species". Virology. 319 (1): 131–140. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2003.10.025. PMID 14967494.

- Huerta, L.; López-Balderas, N.; Rivera-Toledo, E.; Sandoval, G.; Gȑmez-Icazbalceta, G.; Villarreal, C.; Lamoyi, E.; Larralde, C. (2009). "HIV-Envelope–Dependent Cell-Cell Fusion: Quantitative Studies". The Scientific World Journal. 9: 746–763. doi:10.1100/tsw.2009.90. PMC 5823155. PMID 19705036.

- National Institutes of Health (2019-12-27). "Syncytium | Definition | AIDSinfo". Retrieved 2019-12-27.

- "MUMPS, Mumps Virus, Mumps Infection". virology-online.com. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

- MaRajah MM, Bernier A, Buchrieser J, Schwartz O (2021). "The Mechanism and Consequences of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Mediated Fusion and Syncytia Formation". Journal of Molecular Biology: 167280. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167280. PMC 8485708. PMID 34606831.

- Chaves-Medina MJ, Gómez-Ospina JC, García-Perdomo HA (2021). "Molecular mechanisms for understanding the association between TMPRSS2 and beta coronaviruses SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infection: scoping review". Archives of Microbiology. 204 (1): 77. doi:10.1007/s00203-021-02727-3. PMC 8709906. PMID 34953136.

- Buchrieser, Julian; Dufloo, Jérémy; Hubert, Mathieu; Monel, Blandine; Planas, Delphine; Michael Rajah, Maaran; Planchais, Cyril; Porrot, Françoise; Guivel‐Benhassine, Florence; Van der Werf, Sylvie; Casartelli, Nicoletta; Mouquet, Hugo; Bruel, Timothée; Schwartz, Olivier (13 October 2020). "Syncytia formation by SARS‐CoV‐2 infected cells". The EMBO Journal. 39 (23): e106267. bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.07.14.202028. doi:10.15252/embj.2020106267. ISSN 0261-4189. PMC 7646020. PMID 33051876. As of 13 October 2020: accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but not copyedited, typeset, paginated, or proofread.

- Sanders, David W.; Jumper, Chanelle C.; Ackerman, Paul J.; Bracha, Dan; Donlic, Anita; Kim, Hahn; Kenney, Devin; Castello-Serrano, Ivan; Suzuki, Saori; Tamura, Tomokazu; Tavares, Alexander H. (2020-12-14). "SARS-CoV-2 Requires Cholesterol for Viral Entry and Pathological Syncytia Formation". eLife. 10: 10:e65962. doi:10.7554/eLife.65962. PMC 8104966. PMID 33890572.

- "SARS-CoV-2 needs cholesterol to invade cells and form mega cells". phys.org. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- Gallagher, James (23 October 2020). "Covid: Why is coronavirus so deadly?". BBC News.