1846–1860 cholera pandemic

The third cholera pandemic (1846–1860) was the third major outbreak of cholera originating in India in the nineteenth century that reached far beyond its borders, which researchers at UCLA believe may have started as early as 1837 and lasted until 1863.[1] In the Russian Empire, more than one million people died of cholera. In 1853–54, the epidemic in London claimed over 10,000 lives, and there were 23,000 deaths for all of Great Britain. This pandemic was considered to have the highest fatalities of the 19th-century epidemics.[2]

It had high fatalities among populations in Asia, Europe, Africa and North America. In 1854, which was considered the worst year, 23,000 people died in Great Britain.

That year, the British physician John Snow, who was working in a poor area of London, identified contaminated water as the means of transmission of the disease. After the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak he had mapped the cases of cholera in the Soho area in London, and noted a cluster of cases near a water pump in one neighborhood. To test his theory, he convinced officials to remove the pump handle, and the number of cholera cases in the area immediately declined. His breakthrough helped eventually bring the epidemic under control. Snow was a founding member of the Epidemiological Society of London, formed in response to a cholera outbreak in 1849, and he is considered one of the fathers of epidemiology.[3][4][5]

Second pandemic

The second cholera pandemic spread from India, surging outward to all of Europe and northern Africa, then crossing the Atlantic to Canada and the United States, spreading to Mexico and the Caribbean. Many sources differ regarding when the second pandemic ended, and the third pandemic began. There are sources that maintain that the third cholera pandemic started with a surge from Bengal in 1839.[6]

1840s

Over 15,000 people died of cholera in Mecca in 1846.[7] In Russia, between 1847 and 1851, more than one million people died in the country's epidemic.[8]

A two-year outbreak began in England and Wales in 1848, and claimed 52,000 lives.[9] In London, it was the worst outbreak in the city's history, claiming 14,137 lives, over twice as many as the 1832 outbreak. Cholera hit Ireland in 1849 and killed many of the Irish Famine survivors, already weakened by starvation and fever.[10] In 1849, cholera claimed 5,308 lives in the major port city of Liverpool, England, an embarkation point for immigrants to North America, and 1,834 in Hull, England.[11] In 1849, a second major outbreak occurred in Paris.

Cholera, believed spread from Irish immigrant ship(s) from England to the United States, spread throughout the Mississippi river system, killing over 4,500 in St. Louis[11] and over 3,000 in New Orleans.[11] Thousands died in New York, a major destination for Irish immigrants.[11] The outbreak that struck Nashville in 1849–1850 took the life of former U.S. President James K. Polk. During the California Gold Rush, cholera was transmitted along the California, Mormon and Oregon Trails as 6,000 to 12,000[12] are believed to have died on their way to Utah and Oregon in the cholera years of 1849–1855.[11] It is believed cholera claimed more than 150,000 victims in the United States during the two pandemics between 1832 and 1849,[13][14] and also claimed 200,000 victims in Mexico.[15] In Vietnam, cholera outbreak in 1849 killed estimatedly from 800,000 to one million people (8–10% of the kingdom's 1847 population).[16]

1850s

The cholera epidemic in Russia that started in 1847 would last until 1851, killing over one million people. In 1851, a ship coming from Cuba carried the disease to Gran Canaria.[17] It is considered that more than 6,000 people died in the island during summer,[18] out of a population of 58,000.

In 1852, cholera spread east to Indonesia, and later was carried to China and Japan in 1854. The Philippines were infected in 1858 and Korea in 1859. In 1859, an outbreak in Bengal contributed to transmission of the disease by travelers and troops to Iran, Iraq, Arabia and Russia.[7] Japan suffered at least seven major outbreaks of cholera between 1858 and 1902. Between 100,000 and 200,000 people died of cholera in Tokyo in an outbreak in 1858–60.[19]

In 1854, an outbreak of cholera in Chicago took the lives of 5.5 percent of the population (about 3,500 people).[20][21] Providence, Rhode Island suffered an outbreak so widespread that for the next thirty years, 1854 was known there as "The Year of Cholera."[22] In 1853–54, London's epidemic claimed 10,739 lives. In Spain, over 236,000 died of cholera in the epidemic of 1854–55.[23] The disease reached South America in 1854 and 1855, with victims in Venezuela and Brazil.[15] During the third pandemic, Tunisia, which had not been affected by the two previous pandemics, thought Europeans had brought the disease. They blamed their sanitation practices. Some United States scientists began to believe that cholera was somehow associated with African Americans, as the disease was prevalent in the South in areas of black populations. Current researchers note their populations were underserved in terms of sanitation infrastructure, and health care, and they lived near the waterways by which travelers and ships carried the disease.[24]

1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak

The 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak was a severe outbreak of cholera that occurred in 1854 near Broad Street (now Broadwick Street) in the Soho district of London, England, and occurred during the third cholera pandemic. This outbreak, which killed 616 people, is best known for the physician John Snow's study of its causes and his hypothesis that germ-contaminated water was the source of cholera, rather than particles in the air (referred to as "miasma").[25][26]

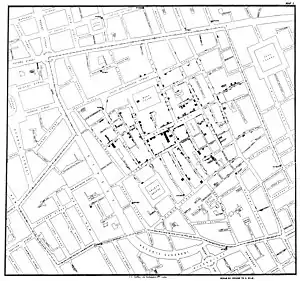

Snow identified the source of an 1854 cholera outbreak as the public water pump on Broad Street (now Broadwick Street). Although his studies were not entirely conclusive, his advocacy convinced the local council to disable the Broad Street pump by removing its handle. Snow later used a dot map to illustrate the cluster of cholera cases around the pump. He also used statistics to illustrate the connection between the quality of the water source and cholera cases, showing that water was being delivered to the outbreak area from sewage-polluted sections of the Thames, leading to an increased incidence of cholera. Snow's study was a major event in the history of public health and geography. It is regarded as one of the founding events of the science of epidemiology.

This discovery came to influence public health and the construction of improved sanitation facilities beginning in the mid-19th century. Later, the term "focus of infection" would be used to describe sites, such as the Broad Street pump, in which conditions are good for transmission of an infection. John Snow's endeavor to find the cause of the transmission of cholera caused him to unknowingly create a double-blind experiment.

See also

References

- Frerichs, Ralph R. "Asiatic Cholera Pandemics During the Life of John Snow : Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1846-63". John Snow - a historical giant in epidemiology. UCLA Department of Epidemiology - Fielding School of Public Health. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "Cholera's seven pandemics". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008.

- "London Epidemiology Society". UCLA. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Dunnigan, M. (2003). "Commentary: John Snow and alum-induced rickets from adulterated London bread: an overlooked contribution to metabolic bone disease". International Journal of Epidemiology. 32 (3): 340–1. doi:10.1093/ije/dyg160. PMID 12777415.

- Snow, J. (1857). "On the Adulteration of Bread As a Cause of Rickets". The Lancet. 70 (1766): 4–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)21130-7.

Reedited in Snow, J. (2003). "On the adulteration of bread as a cause of rickets" (PDF). International Journal of Epidemiology. 32 (3): 336–7. doi:10.1093/ije/dyg153. PMID 12777413. - Hays, J. N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851096589.

- Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1846-63. UCLA School of Public Health.

- Geoffrey A. Hosking (2001). "Russia and the Russians: a history". Harvard University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-674-00473-6

- Cholera's seven pandemics, cbc.ca, 2 December 2008.

- "The Irish Famine". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. (1987). The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-72677-9.

- Unruh, John David (1993). The plains across: the overland emigrants and the trans-Mississippi West, 1840–60. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 408–10. ISBN 978-0-252-06360-2.

- Beardsley GW (2000). "The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State: 19th Century Responses to Cholerae Vibrio (part 2)". The Early America Review. 3 (2). Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- Vibrio cholerae in recreational beach waters and tributaries of Southern California.

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1.

- Goscha, Christopher (2016). Vietnam: A New History. Basic Books. p. 60.

- HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHICAL APPROACH IN THE BEHAVIOR OF THE EPIDEMIC OF THE CHOLERA MORBUS OF 1851 IN THE PALMS OF GREAT CANARY p.626

- Historia de la medicina en Gran Canaria pp. 545–546

- Kaoru Sugihara, Peter Robb, Haruka Yanagisawa, Local Agrarian Societies in Colonial India: Japanese Perspectives, (1996), p. 313.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. (1987). The cholera years: the United States in 1832, 1849 and 1866. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-72677-9.

- Chicago Daily Tribune Archived 31 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 12 July 1854

- McKenna, Ray (19 April 2020). "My Turn: Ray McKenna: R.I. residents of 1854 would relate". The Providence Journal. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Kohn, George C. (2008). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: from Ancient Times to the Present. Infobase Publishing. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-8160-6935-4.

- Hayes, J. N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 233.

- Eyeler, William (July 2001). "The changing assessments of John Snow's and William Farr's Cholera Studies". Sozial- und Präventivmedizin. 46 (4): 225–32. doi:10.1007/BF01593177. PMID 11582849. S2CID 9549345.

- Paneth, N; Vinten-Johansen, P; Brody, H; Rip, M (1 October 1998). "A rivalry of foulness: official and unofficial investigations of the London cholera epidemic of 1854". American Journal of Public Health. 88 (10): 1545–1553. doi:10.2105/ajph.88.10.1545. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 1508470. PMID 9772861.