Visual impairment due to intracranial pressure

Spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS),[1] previously known as Spaceflight-induced visual impairment,[2] is hypothesized to be a result of increased intracranial pressure. The study of visual changes and intracranial pressure (ICP) in astronauts on long-duration flights is a relatively recent topic of interest to Space Medicine professionals. Although reported signs and symptoms have not appeared to be severe enough to cause blindness in the near term, long term consequences of chronically elevated intracranial pressure is unknown.[3]

NASA has reported that fifteen long-duration male astronauts (45–55 years of age) have experienced confirmed visual and anatomical changes during or after long-duration flights.[4] Optic disc edema, globe flattening, choroidal folds, hyperopic shifts and an increased intracranial pressure have been documented in these astronauts. Some individuals experienced transient changes post-flight while others have reported persistent changes with varying degrees of severity.[5]

Although the exact cause is not known, it is suspected that microgravity-induced cephalad fluid shift and comparable physiological changes play a significant role in these changes.[5] Other contributing factors may include pockets of increased CO2 and an increase in sodium intake. It seems unlikely that resistive or aerobic exercise are contributing factors, but they may be potential countermeasures to reduce intraocular pressure (IOP) or intracranial pressure (ICP) in-flight.[4]

Causes and current studies

Although a definitive cause (or set of causes) for the symptoms outlined in the Existing Long-Duration Flight Occurrences section is unknown, it is thought that venous congestion in the brain brought about by cephalad-fluid shifts may be a unifying pathologic mechanism.[6] Additionally, a recent study reports changes in CSF hydrodynamics and increased diffusivity around the optic nerve under simulated microgravity conditions which may contribute to ocular changes in spaceflight.[7] As part of the effort to elucidate the cause(s), NASA has initiated an enhanced occupational monitoring program for all mission astronauts with special attention to signs and symptoms related to ICP.

Similar findings have been reported among Russian Cosmonauts who flew long-duration missions on MIR. The findings were published by Mayasnikov and Stepanova in 2008.[8]

Animal research from the Russian Bion-M1 mission indicates duress of the cerebral arteries may induce reduced blood flow, thereby contributing to impaired vision.[9]

On 2 November 2017, scientists reported that significant changes in the position and structure of the brain have been found in astronauts who have taken trips in space, based on MRI studies. Astronauts who took longer space trips were associated with greater brain changes.[10][11]

CO2

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a natural product of metabolism. People typically exhale around 200mL of CO2 per minute at rest and over 4.0 L at peak exercise levels.[12] In a closed environment, CO2 levels can quickly rise and can be expected to a certain degree in an environment such as the ISS. Nominal CO2 concentrations on Earth are approximately 0.23 mmHg [13] while nominal CO2 levels aboard the ISS are up to 20 times that at 2.3 to 5.3 mmHg. Those astronauts who experienced VIIP symptoms were not exposed to CO2 levels in excess of 5 mmHg.[14][15]

Ventilation and heart rate increase as CO2 rise. Hypercapnia also stimulates vasodilation of cerebral blood vessels, increased cerebral blood flow and elevated ICP presumably leading to headache, visual disturbance and other central nervous system (CNS) symptoms. CO2 is a known potent vasodilator and an increase in cerebral perfusion pressure will increase the CSF fluid production by about 4%.[16]

Since air movement is reduced in microgravity, local pockets of increased CO2 concentrations may form. Without proper ventilation, CO2 concentrations ppCO2 could rise above 9mmHg within 10 minutes around a sleeping astronaut's mouth and chin.[17] More data is needed to fully understand the individual and environmental factors that contribute to CO2-related symptoms in microgravity.

Sodium intake

A link between increased ICP and altered sodium and water retention was suggested by a report in which 77% of IIH patients had evidence of peripheral edema and 80% with orthostatic retention of sodium and water.[18] Impaired saline and water load excretions were noted in the upright position in IIH patients with orthostatic edema compared to lean and obese controls without IIH. However, the precise mechanisms linking orthostatic changes to IIH were not defined, and many IH patients do not have these sodium and water abnormalities. Astronauts are well known to have orthostatic intolerance upon reentry to gravity after long-duration spaceflight, and the dietary sodium on orbit is also known to be in excess of 5 grams per day in some cases. The Majority of the NASA cases did have high dietary sodium during their increment. The ISS program is working to decrease in-flight dietary sodium intake to less than 3 grams per day.[18] Prepackaged foods for the International Space Station were originally high in sodium at 5300 mg/d. This amount has now been substantially reduced to 3000 mg/d as a result of NASA reformulation of over ninety foods as a conscious effort to reduce astronaut sodium intake.[19]

Exercise

While exercise is used to maintain muscle, bone and cardiac health during spaceflight, its effects on ICP and IOP have yet to be determined. The effects of resistive exercise on the development of ICP remains controversial. An early investigation showed that the brief intrathoracic pressure increase during a Valsalva maneuver resulted in an associated rise in ICP.[20] Two other investigations using transcranial Doppler ultrasound techniques showed that resistive exercise without a Valsalva maneuver resulted in no change in peak systolic pressure or ICP.[21][22][23] The effects of resistive exercise in IOP are less controversial. Several different studies have shown a significant increase in IOP during or immediately after resistive exercise.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30]

There is much more information available regarding aerobic exercise and ICP. The only known study to examine ICP during aerobic exercise by invasive means showed that ICP decreased in patients with intracranial hypertension and those with normal ICP.[31] They suggested that because aerobic exercise is generally done without Valsalva maneuvers, it is unlikely that ICP will increase during exercise. Other studies show global brain blood flow increases 20–30% during the transition from rest to moderate exercise.[32][33]

More recent work has shown that an increase in exercise intensity up to 60% VO2max results in an increase in CBF, after which CBF decreases towards (and sometimes below) baseline values with increasing exercise intensity.[34][35][36][37]

Biomarkers

Several biomarkers may be used for early VIIP Syndrome detection. The following biomarkers were suggested as potential candidates by the 2010 Visual Impairment Summit:[38]

- albumin

- aquaporin

- atrial naturetic peptide

- CRP/inflammation markers

- immunoglobin G index

- insulin-like growth factors

- myelin basic protein

- oligoclonal bands

- platelet count

- S-100

- somatostatin

- tet-transactivator (TTA)

- vasopressin

Also, gene expression profiling, epigenetic modifications, CO2 retaining variants, single-nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants should be expanded in order to better characterize the individual susceptibility to develop the VIIP syndrome. As the etiology of the symptoms is more clearly defined, the appropriate biomarkers will be evaluated.

One-carbon metabolism (homocysteine)

While the common theories regarding vision issues during flight focus on cardiovascular factors (fluid shift, intracranial hypertension, CO2 exposure, etc.), the difficulty comes in trying to explain how on any given mission, breathing the same air and exposed to the same microgravity, why some crewmembers have vision issues while others do not. Data identified as part of an ongoing nutrition experiment found biochemical evidence that the folate-dependent one-carbon metabolic pathway may be altered in those individuals who have vision issues. These data have been published[39] and summarized by the ISS Program,[40] and described in a journal sponsored pubcast.[41]

In brief: serum concentrations of metabolites of the folate, vitamin B-12 dependent one carbon metabolism pathway, specifically, homocysteine, cystathionine, 2-methylcitric acid, and methylmalonic acid were all significantly (P<0.001) higher (25–45%) in astronauts with ophthalmic changes than in those without such changes. These differences existed before, during, and after flight. Serum folate tended to be lower (P=0.06) in individuals with ophthalmic changes. Preflight serum concentrations of cystathionine and 2-methylcitric acid, and mean in-flight serum folate, were significantly (P<0.05) correlated with changes in refraction (postflight relative to preflight).

Thus, data from the Nutrition SMO 016E provide evidence for an alternative hypothesis: that individuals with alterations in this metabolic pathway may be predisposed to anatomic and/or physiologic changes that render them susceptible to ophthalmologic damage during space flight. A follow-up project has been initiated (the "One Carbon" study) to follow up and clarify these preliminary findings.

Space obstructive syndrome

An anatomic cause of the microgravity related intracranial hypertension and visual disturbances has been proposed and is termed Space Obstructive Syndrome or SOS. This hypothesis has the possibility of linking the various symptoms and signs together through a common mechanism in a cascade phenomenon, and explaining the findings in one individual and not another due to specific anatomic variations in the structural placement of the internal jugular vein. This hypothesis was presented in May 2011 at the annual meeting of the Aerospace Medicine Association in Anchorage, Alaska, and was published in January, 2012.[42]

In 1G on earth, the main outflow of blood from the head is due to gravity, rather than a pumping or vacuum mechanism. In a standing position, the main outflow from the head is through the vertebral venous system because the internal jugular veins, located primarily between the carotid artery and the sternocleidomastoid muscle are partially or completely occluded due to the pressure from these structures, and in a supine position, the main outflow is through the internal jugular veins as they have fallen laterally due to the weight of the contained blood, are no longer compressed and have greatly expanded in diameter, but the smaller vertebral system has lost the gravitational force for blood outflow. In microgravity, there is no gravity to pull the internal jugular veins out from the zone of compression (Wiener classification Zone I), and there is also no gravitational force to pull blood through the vertebral venous system. In microgravity, the cranial venous system has been put into minimal outflow and maximal obstruction. This then causes a cascade of cranial venous hypertension, which decreases CSF resorption from the arachnoid granulations, leading to intracranial hypertension and papilledema. The venous hypertension also contributes to the head swelling seen in photos of astronauts and the nasal and sinus congestion along with headache noted by many. There is also subsequent venous hypertension in the venous system of the eye which may contribute to the findings noted on ophthalmic exam and contributing to the visual disturbances noted.

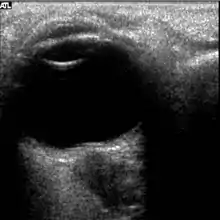

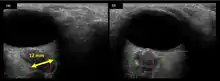

The astronauts affected by long term visual changes and prolonged intracranial hypertension have all been male, and SOS may explain this because in men, the sternocleidomastoid muscle is typically thicker than in women and may contribute to more compression. The reason that SOS does not occur in all individuals may be related to anatomic variations in the internal jugular vein. Ultrasound study has shown that in some individuals, the internal jugular vein is located in a more lateral position to Zone I compression, and therefore not as much compression will occur, allowing continued blood flow.

Current ICP and IOP measurement

ICP measurement

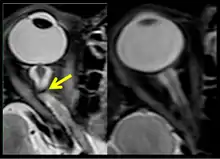

Intracranial pressure (ICP) needs to be directly measured before and after long duration flights to determine if microgravity causes the increased ICP. On the ground, lumbar puncture is the standard method of measuring cerebral spinal fluid pressure and ICP,[5][43] but this carries additional risk in-flight.[3] NASA is determining how to correlate ground-based MRI with inflight ultrasound[3] and other methods of measuring ICP in space is currently being investigated.[43]

To date, NASA has measured intraocular pressure (IOP), visual acuity, cycloplegic refraction, Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and A-scan axial length changes in the eye before and after spaceflight.[44]

Non-invasive ICP measurement

There are different approaches to non-invasive intracranial pressure measurement, which include ultrasound "time-of-flight" techniques, transcranial Doppler, methods based on acoustic properties of the cranial bones, EEG, MRI, tympanic membrane displacement, oto-acoustic emission, ophthalmodynamometry, ultrasound measurements of optic nerve sheath diameter, and Two-Depth Transorbital Doppler. Most of the approaches are "correlation based". Such approaches can not measure an absolute ICP value in mmHg or other pressure units because of the need for individual patient specific calibration. Calibration needs non-invasive "gold standard" ICP meter which does not exists. Non-invasive absolute intracranial pressure value meter, based on ultrasonic Two-Depth Transorbital Doppler technology, has been shown to be accurate and precise in clinical settings and prospective clinical studies. Analysis of the 171 simultaneous paired recordings of non-invasive ICP and the "gold standard" invasive CSF pressure on 110 neurological patients and TBI patients showed good accuracy for the non-invasive method as indicated by the low mean systematic error (0.12 mmHg; confidence level (CL) = 0.98). The method also showed high precision as indicated by the low standard deviation (SD) of the random errors (SD = 2.19 mmHg; CL = 0.98).[45] This measurement method and technique (the only non-invasive ICP measurement technique which already received EU CE Mark approval) eliminates the main limiting problem of all other non-successful "correlation based" approaches to non-invasive ICP absolute value measurement – the need of calibration to the individual patient.[46]

IOP measurement

Intraocular pressure (IOP) is determined by the production, circulation and drainage of ocular aqueous humor and is described by the equation:

Where:

- F = aqueous fluid formation rate

- C = aqueous outflow rate

- PV = episcleral venous pressure

In general populations IOP ranges between and 20 mmHg with an average of 15.5 mmHg, aqueous flow averages 2.9 μL/min in young healthy adults and 2.2 μL/min in octogenarians, and episcleral venous pressure ranges from 7 to 14 mmHg with 9 to 10 mmHg being typical.

Existing long-duration flight occurrences

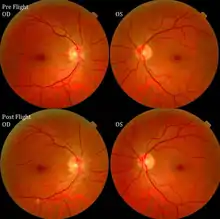

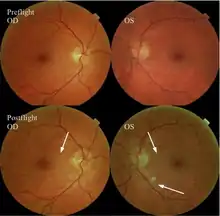

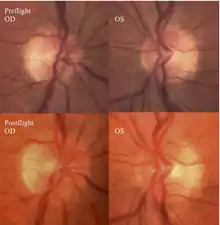

The first U.S. case of visual changes observed on orbit was reported by a long-duration astronaut that noticed a marked decrease in near-visual acuity throughout his mission on board the ISS, but at no time reported headaches, transient visual obscurations, pulsatile tinnitus or diplopia (double vision). His postflight fundus examination (Figure 1) revealed choroidal folds below the optic disc and a single cotton-wool spot in the inferior arcade of the right eye. The acquired choroidal folds gradually improved, but were still present 3 year postflight. The left eye examination was normal. There was no documented evidence of optic-disc edema in either eye. Brain MRI, lumbar puncture, and OCT were not performed preflight or postflight on this astronaut.[4]

The second case of visual changes during long-duration spaceflight on board the ISS was reported approximately 3 months after launch when the astronaut noticed that he could now only see Earth clearly while looking through his reading glasses. The change continued for the remainder of the mission without noticeable improvement or progression. He did not complain of transient visual obscurations, headaches, diplopia, pulsatile tinnitus or visual changes during eye movement. In the months since landing, he has noticed a gradual, but incomplete, improvement in vision.[4]

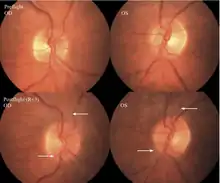

The third case of visual changes while on board the ISS had no changes in visual acuity and no complaints of headaches, transient visual obscurations, diplopia or pulsatile tinnitus during the mission. Upon return to Earth, no eye issues were reported by the astronaut at landing. Fundus examination revealed bilateral, asymmetrical disc edema. There was no evidence of choroidal folds or cotton-wool spots, but a small hemorrhage was observed below the optic dics in the right eye. This astronaut had the most pronounced optic-disc edema of all astronauts reported to date, but had no choroidal folds, globe flattening or hyperopic shift. At 10 days post landing, an MRI of the brain and eyes was normal, but there appeared to be a mild increase in CSF signal around the right optic nerve.[4]

The fourth case of visual changes on orbit was significant for a history of transsphenoidal hypophysectomy for macroadenoma where postoperative imaging showed no residual or recurrent disease. Approximately 2 months into the ISS mission, the astronaut noticed a progressive decrease in near-visual acuity in his right eye and a scotoma in his right temporal field of vision.[4]

During the same mission, another ISS long-duration astronaut reported the fifth case of decreased near-visual acuity after 3 weeks of spaceflight. In both cases, CO2, cabin pressure and oxygen levels were reported to be within acceptable limits and the astronauts were not exposed to any toxic fumes.[4]

The fifth case of visual changes observed on the ISS was noticed only 3 weeks into his mission. This change continued for the remainder of the mission without noticeable improvement or progression. He never complained of headaches, transient visual obscurations, diplopia, pulsatile tinnitus or other visual changes. Upon return to Earth, he noted persistence of the vision changes he observed in space. He never experienced losses in subjective best-corrected acuity, color vision or stereopsis. This case is interesting because the astronaut did not have disc edema or choroidal folds, but was documented to have nerve fiber layer (NFL) thickening, globe flattening, a hyperopic shift and subjective complaints of loss of near vision.[4]

The sixth case of visual changes of an ISS astronaut was reported after return to Earth from a 6-month mission. When he noticed that his far vision was clearer through his reading glasses. A fundus examination performed 3 weeks postflight documented a grade 1 nasal optic-disc edema in the right eye only. There was no evidence of disc edema in the left eye or choroidal folds in either eye (Figure 13). MRI of the brain and eyes days postflight revealed bilateral flattening of the posterior globe, right greater than left, and a mildly distended right optic nerve sheath. There was also evidence of optic-disc edema in the right eye. A fundus examination postflight revealed a "new onset" cotton-wool spot in the left eye. This was not observed in the fundus photographs taken 3 weeks postflight.[4]

The seventh case of visual changes associated with spaceflight is significant in that it was eventually treated postflight. Approximately 2 months into the ISS mission, the astronaut reported a progressive decrease in his near and far acuity in both eyes. The ISS cabin pressure, CO2 and O2 levels were reported to be within normal operating limits and the astronaut was not exposed to any toxic substances. He never experienced losses in subjective best-corrected acuity, color vision or stereopsis. A fundus examination revealed a grade 1 bilateral optic-disc edema and choroidal folds (Figure 15).[4]

Case definition and clinical practice guidelines

According to guidelines set forth by the Space Medicine Division, all long-duration astronauts with postflight vision changes should be considered a suspected case of VIIP syndrome. Each case could then be further differentiated by definitive imaging studies establishing the postflight presence of optic-disc edema, increased ONSD and altered OCT findings. The results from these imaging studies are then divided into five classes that determine what follow-up testing and monitoring is required.

Classes

The definition of the classes and Frisén scale used for optic disc edema diagnosis are listed below:

Class 0

- < 0.50 diopter cycloplegic refractive change

- No evidence of optic-disc edema, nerve sheath distention, choroidal folds, globe flattening, scotoma or cotton-wool spots compared to baseline

Class 1

Repeat OCT and visual acuity in 6 weeks

- Refractive changes ≥ 0.50 diopter cycloplegic refractive change and/or cotton-wool spot

- No evidence of optic-disc edema, nerve sheath distention, choroidal folds, globe flattening or scotoma compared to baseline

- CSF opening pressure ≤ 25 cm H2O (if measured)

Class 2

Repeat OCT, cycloplegic refraction, fundus examination and threshold visual field every 4 to 6 weeks × 6 months, repeat MRI in 6 months

- ≥ 0.50 diopter cycloplegic refractive changes or cotton-wool spot

- Choroidal folds and/or ONS distention and/or globe flattening and/or scotoma

- No evidence of optic-disc edema

- CSF opening pressure ≤ 25 cm H2O (if measured)

Class 3

Repeat OCT, cycloplegic refraction, fundus examination and threshold visual field every 4 to 6 weeks × 6 months, repeat MRI in 6 months

- ≥ 0.50 diopter cycloplegic refractive changes and/or cotton-wool spot

- Optic nerve sheath distention, and/or globe flattening and/or choroidal folds and/or scotoma

- Optic-disc edema of Grade 0-2

- CSF opening pressure ≤ 25 cm H2O

Class 4

Institute treatment protocol as per Clinical Practice Guideline

- ≥ 0.50 diopter cycloplegic refractive changes and/or cotton-wool spot

- Optic nerve sheath distention, and/or globe flattening and/or choroidal folds and/or scotoma

- Optic-disc edema Grade 2 or above

- Presenting symptoms of new headache, pulsatile tinnitus and/or transient visual obscurations

- CSF opening pressure > 25 cm H2O

Stages

Optic-disc edema will be graded based on the Frisén Scale[47] as below:

Stage 0 – Normal Optic-disc

Blurring of nasal, superior and inferior poles in inverse proportion to disc diameter. Radial nerve fiber layer (NFL) without NFL tortuosity. Rare obscuration of a major blood vessel, usually on the upper pole.

Stage 1 – Very early optic-disc edema

Obscuration of the nasal border of the disc. No elevation of the disc borders. Disruption of the normal radial NFL arrangement with grayish opacity accentuating nerve fiber layer bundles. Normal temporal disc margin. Subtle grayish halo with temporal gap (best seen with indirect ophthalmoscopy). Concentric or radial retrochoroidal folds.

Stage 2 – Early optic-disc edema

Obscuration of all borders. Elevation of the nasal border. Complete peripapillary halo.

Stage 3 – Moderate optic-disc edema

Obscurations of all borders. Increased diameter of ONH. Obscuration of one or more segments of major blood vessels leaving the disc. Peripapillary halo – irregular outer fringe with finger-like extensions.

Stage 4 – Marked optic-disc edema

Elevation of the entire nerve head. Obscuration of all borders. Peripapillary halo. Total obscuration on the disc of a segment of a major vessel.

Stage 5 – Severe optic-disc edema

Dome-shaped protrusions representing anterior expansion of the ONG. Peripapillary halo is narrow and smoothly demarcated. Total obscuration of a segment of a major blood vessel may or may not be present. Obliteration of the optic cup.

Risk factors and recommendations

Risk factors and underlying mechanisms based on anatomy, physiology, genetics and epigenetics need to be researched further.[48]

The following actions have been recommended to assist in the research of vision impairment and increased intracranial pressure associated with long-duration space flight:[49]

Immediate actions

- Correlate pre-flight and post-flight MRIs with in-flight Ultrasound

- Directly measure intracranial pressure through lumbar puncture pre-flight and post-flight on all long duration astronauts

- Due to the normal variability in this measurement, obtain more than one pre-flight intracranial pressure measurement through lumbar puncture

- Enhanced analysis of OCT findings such as RPE angle

- Blinded readings of previous and future diagnostic imaging to minimize potential bias

- Measurement of in-flight IOP on all astronauts

- Improved in-flight fundoscopic imaging capability

- Measurement of pre-flight and post-flight compliance (cranial, spinal, vascular)

Near and long-term actions

- Establish case definition based on current Medical Requirements Integration Documents (MRID) and clinical findings

- Develop clinical practice guidelines

- Establish a reliable and accurate non-invasive in-flight capability to measure and monitor ICP, compliance and cerebral blood flow

- Develop more sophisticated in-flight neurocognitive testing

- Establish risk stratification and underlying mechanisms based on anatomy and physiology

- Characterization of Human Spaceflight Physiology and Anatomy (human and animal tissue studies)

- Develop or utilize advance imaging modalities (Near Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS), Transcranial Doppler (TCD), Ophthalmodynanometry, Venous Doppler Ultrasound)

- Genetic testing and the use of biomarkers in blood and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF)

Benefits to Earth

The development of accurate and reliable non-invasive ICP measurement methods for VIIP has the potential to benefit many patients on earth who need screening and/or diagnostic ICP measurements, including those with hydrocephalus, intracranial hypertension, intracranial hypotension, and patients with cerebrospinal fluid shunts. Current ICP measurement techniques are invasive and require either a lumbar puncture, insertion of a temporary spinal catheter,[50] insertion of a cranial ICP monitor, or insertion of a needle into a shunt reservoir.[51]

See also

References

Citations

- Martin Paez Y, Mudie LI, Subramanian PS (2020). "Spaceflight Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome (SANS): A Systematic Review and Future Directions". Eye and Brain. 12: 105–117. doi:10.2147/EB.S234076. PMC 7585261. PMID 33117025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chang, Kenneth (27 January 2014). "Beings Not Made for Space". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "The Visual Impairment Intracranial Pressure Summit Report" (PDF). NASA. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Otto, C.; Alexander, DJ; Gibson, CR; Hamilton, DR; Lee, SMC; Mader, TH; Oubre, CM; Pass, AF; Platts, SH; Scott, JM; Smith, SM; Stenger, MB; Westby, CM; Zanello, SB (12 July 2012). "Evidence Report: Risk of spaceflight-induced intracranial hypertension and vision alterations" (PDF). Human Research Program: Human Health Countermeasures Element.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The Visual Impairment Intracranial Pressure Summit Report" (PDF). NASA. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Howell, Elizabeth (3 November 2017). "Brain Changes in Space Could Be Linked to Vision Problems in Astronauts". Seeker. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Gerlach, D; Marshall-Goebel, K; Hasan, K; Kramer, L; Alpern, N; Rittweger, J, SI (2017). "MRI-derived diffusion parameters in the human optic nerve and its surrounding sheath during head-down tilt". NPJ Microgravity. 3: 18. doi:10.1038/s41526-017-0023-y. PMC 5479856. PMID 28649640.

- Mayasnikov, VI; Stepanova, SI (2008). "Features of cerebral hemodynamics in cosmonauts before and after flight on the MIR Orbital Station". Orbital Station MIR. 2: 300–305.

- Marwaha, Nikita (2013). "In Focus: Why Spaceflight is Becoming Blurrier over Time". Space Safety Magazine. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- Roberts, Donna R.; et al. (2 November 2017). "Effects of Spaceflight on Astronaut Brain Structure as Indicated on MRI". New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (18): 1746–1753. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1705129. PMID 29091569. S2CID 205102116.

- Foley, Katherine Ellen (3 November 2017). "Astronauts who take long trips to space return with brains that have floated to the top of their skulls". Quartz. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Williams, WJ (2009). "Physiological responses to oxygen and carbon dioxide in the breathing environment" (PDF). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Public Meeting slides. Pittsburgh, PA.

- James, JT (2007). "The headache of carbon dioxide exposures". Society of Automotive Engineers: 071CES–42.

- Bacal, K; Beck, G; Barratt, MR (2008). S.L. Pool, M.R. Barratt (ed.). "Hypoxia, hypercarbia and atmospheric control". Principles of Clinical Medicine for Space Flight: 459.

- Wong, KL (1996). "Carbon Dioxide". In N.R. Council (ed.). Spacecraft maximum allowable concentrations for selected airborne contaminants. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press. pp. 105–188.

- Ainslie, P. N.; Duffin, J. (2009). "Integration of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and chemoreflex control of breathing: Mechanisms of regulation, measurement, and interpretation". AJP: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 296 (5): R1473–95. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.91008.2008. PMID 19211719. S2CID 32243137.

- Son, Chang H.; Zapata, Jorge L.; Lin, Chao-Hsin (2002). "Investigation of Airflow and Accumulation of Carbon Dioxide in the Service Module Crew Quarters". SAE Technical Paper Series. SAE Technical Paper Series. Vol. 1. doi:10.4271/2002-01-2341.

- Smith, Scott M.; Zwart, Sara R. (2008). Chapter 3 Nutritional Biochemistry of Spaceflight. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. Vol. 46. pp. 87–130. doi:10.1016/S0065-2423(08)00403-4. ISBN 9780123742094. PMID 19004188.

- Lane, Helen W.; Bourland, Charles; Barrett, Ann; Heer, Martina; Smith, Scott M. (2013). "The Role of Nutritional Research in the Success of Human Space Flight". Advances in Nutrition. 4 (5): 521–523. doi:10.3945/an.113.004101. PMC 3771136. PMID 24038244.

- Junqueira, L. F. (2008). "Teaching cardiac autonomic function dynamics employing the Valsalva (Valsalva-Weber) maneuver". Advances in Physiology Education. 32 (1): 100–6. doi:10.1152/advan.00057.2007. PMID 18334576. S2CID 1333570.

- Edwards, Michael R.; Martin, Donny H.; Hughson, Richard L. (2002). "Cerebral hemodynamics and resistance exercise". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 34 (7): 1207–1211. doi:10.1097/00005768-200207000-00024. PMID 12131264. S2CID 7953424.

- Pott, Frank; Van Lieshout, Johannes J.; Ide, Kojiro; Madsen, Per; Secher, Niels H. (2003). "Middle cerebral artery blood velocity during intense static exercise is dominated by a Valsalva maneuver". Journal of Applied Physiology. 94 (4): 1335–44. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00457.2002. PMID 12626468. S2CID 26487209.

- Haykowsky, Mark J.; Eves, Neil D.; r. Warburton, Darren E.; Findlay, Max J. (2003). "Resistance Exercise, the Valsalva Maneuver, and Cerebrovascular Transmural Pressure". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 35 (1): 65–8. doi:10.1097/00005768-200301000-00011. PMID 12544637. S2CID 28656724.

- Lempert, P; Cooper, KH; Culver, JF; Tredici, TJ (June 1967). "The effect of exercise on intraocular pressure". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 63 (6): 1673–6. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(67)93645-8. PMID 6027342.

- Movaffaghy, A.; Chamot, S.R.; Petrig, B.L.; Riva, C.E. (1998). "Blood Flow in the Human Optic Nerve Head during Isometric Exercise". Experimental Eye Research. 67 (5): 561–8. doi:10.1006/exer.1998.0556. PMID 9878218.

- Vieira, Geraldo Magela; Oliveira, Hildeamo Bonifácio; De Andrade, Daniel Tavares; Bottaro, Martim; Ritch, Robert (2006). "Intraocular Pressure Variation During Weight Lifting". Archives of Ophthalmology. 124 (9): 1251–4. doi:10.1001/archopht.124.9.1251. PMID 16966619.

- Dickerman, RD; Smith, GH; Langham-Roof, L; McConathy, WJ; East, JW; Smith, AB (April 1999). "Intra-ocular pressure changes during maximal isometric contraction: does this reflect intra-cranial pressure or retinal venous pressure?". Neurological Research. 21 (3): 243–6. doi:10.1080/01616412.1999.11740925. PMID 10319330.

- Marcus, DF; Edelhauser, HF; Maksud, MG; Wiley, RL (September 1974). "Effects of a sustained muscular contraction on human intraocular pressure". Clinical Science and Molecular Medicine. 47 (3): 249–57. doi:10.1042/cs0470249. PMID 4418651.

- Avunduk, Avni Murat; Yilmaz, Berna; Sahin, Nermin; Kapicioglu, Zerrin; Dayanir, Volkan (1999). "The Comparison of Intraocular Pressure Reductions after Isometric and Isokinetic Exercises in Normal Individuals". Ophthalmologica. 213 (5): 290–4. doi:10.1159/000027441. PMID 10516516. S2CID 2118146.

- Chromiak, JA; Abadie, BR; Braswell, RA; Koh, YS; Chilek, DR (November 2003). "Resistance training exercises acutely reduce intraocular pressure in physically active men and women". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 17 (4): 715–20. doi:10.1519/00124278-200311000-00015. PMID 14636115.

- Brimioulle, Serge; Moraine, Jean-Jacques; Norrenberg, Danielle; Kahn, Robert J (December 1997). "Effects of Positioning and Exercise on Intracranial Pressure in a Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit". Physical Therapy. 77 (12): 1682–9. doi:10.1093/ptj/77.12.1682. PMID 9413447.

- Kashimada, A; Machida, K; Honda, N; Mamiya, T; Takahashi, T; Kamano, T; Osada, H (March 1995). "Measurement of cerebral blood flow with two-dimensional cine phase-contrast mR imaging: evaluation of normal subjects and patients with vertigo". Radiation Medicine. 13 (2): 95–102. PMID 7667516.

- Delp, Michael D.; Armstrong, R. B.; Godfrey, Donald A.; Laughlin, M. Harold; Ross, C. David; Wilkerson, M. Keith (2001). "Exercise increases blood flow to locomotor, vestibular, cardiorespiratory and visual regions of the brain in miniature swine". The Journal of Physiology. 533 (3): 849–59. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00849.x. PMC 2278667. PMID 11410640.

- Jørgensen, LG; Perko, G; Secher, NH (November 1992). "Regional cerebral artery mean flow velocity and blood flow during dynamic exercise in humans". Journal of Applied Physiology. 73 (5): 1825–30. doi:10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.1825. PMID 1474058.

- Jørgensen, LG; Perko, M; Hanel, B; Schroeder, TV; Secher, NH (March 1992). "Middle cerebral artery flow velocity and blood flow during exercise and muscle ischemia in humans". Journal of Applied Physiology. 72 (3): 1123–32. doi:10.1152/jappl.1992.72.3.1123. PMID 1568967.

- Hellström, G; Fischer-Colbrie, W; Wahlgren, NG; Jogestrand, T (July 1996). "Carotid artery blood flow and middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity during physical exercise". Journal of Applied Physiology. 81 (1): 413–8. doi:10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.413. PMID 8828693.

- Moraine, J. J.; Lamotte, M.; Berré, J.; Niset, G.; Leduc, A.; Naeije, R. (1993). "Relationship of middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity to intensity during dynamic exercise in normal subjects". European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 67 (1): 35–8. doi:10.1007/BF00377701. PMID 8375362. S2CID 24245272.

- "The Visual Impairment Intracranial Pressure Summit Report" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-11.

- Zwart, S. R.; Gibson, C. R.; Mader, T. H.; Ericson, K.; Ploutz-Snyder, R.; Heer, M.; Smith, S. M. (2012). "Vision Changes after Spaceflight Are Related to Alterations in Folate- and Vitamin B-12-Dependent One-Carbon Metabolism". Journal of Nutrition. 142 (3): 427–31. doi:10.3945/jn.111.154245. PMID 22298570.

- Keith, L. "New Findings on Astronaut Vision Loss". International Space Station. NASA.

- Zwart, S; Gibson, CR; Mader, TH; Ericson, K; Ploutz-Snyder, R; Heer, M; Smith, SM (2012). "Vision Changes after Spaceflight Are Related to Alterations in Folate– and Vitamin B-12–Dependent One-Carbon Metabolism". SciVee. 142 (3): 427–31. doi:10.3945/jn.111.154245. PMID 22298570.

- Wiener, TC (January 2012). "Space obstructive syndrome: intracranial hypertension, intraocular pressure, and papilledema in space". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 83 (1): 64–66. doi:10.3357/ASEM.3083.2012. PMID 22272520.

- "The Visual Impairment Intracranial Pressure Summit Report" (PDF). NASA. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- "The Visual Impairment Intracranial Pressure Summit Report" (PDF). NASA. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Ragauskas A, Matijosaitis V, Zakelis R, Petrikonis K, Rastenyte D, Piper I, Daubaris G; Matijosaitis; Zakelis; Petrikonis; Rastenyte; Piper; Daubaris (May 2012). "Clinical assessment of noninvasive intracranial pressure absolute value measurement method". Neurology. 78 (21): 1684–91. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182574f50. PMID 22573638. S2CID 45033245.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - News-Medical.net. http://www.news-medical.net/news/20120705/Non-invasive-absolute-intracranial-pressure-value-meter-shown-to-be-accurate-in-clinical-settings.aspx%5B%5D

- Frisén, L (January 1982). "Swelling of the optic nerve head: a staging scheme". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 45 (1): 13–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.45.1.13. PMC 491259. PMID 7062066.

- "The Visual Impairment Intracranial Pressure Summit Report" (PDF). NASA. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- "The Visual Impairment Intracranial Pressure Summit Report" (PDF). NASA. pp. 9–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Torbey, MT; Geocadin RG; Razumovsky AY; Rigamonti D; Williams MA (2004). "Utility of CSF pressure monitoring to identify idiopathic intracranial hypertension without papilledema in patients with chronic daily headache". Cephalalgia. 24 (6): 495–502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00688.x. PMID 15154860. S2CID 25829389.

- Geocadin, RG; Varelas PN; Rigamonti D; Williams MA (April 2007). "Continuous intracranial pressure monitoring via the shunt reservoir to assess suspected shunt malfunction in adults with hydrocephalus". Neurosurg Focus. 22 (4): E10. doi:10.3171/foc.2007.22.4.12. PMID 17613188.

Sources

This article incorporates public domain material from The Visual Impairment Intracranial Pressure Summit Report (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from The Visual Impairment Intracranial Pressure Summit Report (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. This article incorporates public domain material from Evidence Report: Risk of Spaceflight-Induced Intracranial Hypertension and Vision Alterations (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from Evidence Report: Risk of Spaceflight-Induced Intracranial Hypertension and Vision Alterations (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Further reading

- Brandon R Macias, John HK Liu, Christian Otto, Alan R Hargens (2017). "Intracranial Pressure & its Effect on Vision in Space and on Earth".

- Mader TH, Gibson CR, Pass AF, et al. (October 2011). "Optic disc edema, globe flattening, choroidal folds, and hyperopic shifts observed in astronauts after long-duration space flight". Ophthalmology. 118 (10): 2058–69. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.021. PMID 21849212.

- "What's New in Space Medicine – Can you say "VIIP"?" (PDF). The Lifetime Surveillance of Astronaut Health. 18 (1). Spring 2012.

- Geeraerts T, Merceron S, Benhamou D, Vigué B, Duranteau J; Merceron; Benhamou; Vigué; Duranteau (November 2008). "Non-invasive assessment of intracranial pressure using ocular sonography in neurocritical care patients". Intensive Care Med. 34 (11): 2062–7. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1149-x. PMC 4088488. PMID 18509619.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dallas, Mary Elizabeth. "Space Travel Might Lead to Eye Trouble: Study". philly.com. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- "Space missions may damage eyes". American Medical Network. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- "Eye Problems Common in Astronauts". Discovery.com. March 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- "Space flight linked to eye, brain problems". CBC News. March 2012.

- Matthews, Mark K. (September 2011). "Blurred vision plagues astronauts who spend months in space". Orlando Sentinel.

- Love, Shayla (9 July 2016). "The mysterious syndrome impairing astronauts' sight". Washington Post.

- Kinyoun, JL; Chittum, ME; Wells, CG (15 May 1988). "Photocoagulation treatment of radiation retinopathy". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 105 (5): 470–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(88)90237-1. PMID 3369516.

- Zhang, LF; Hargens, AR (January 2014). "Intraocular/Intracranial pressure mismatch hypothesis for visual impairment syndrome in space". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 85 (1): 78–80. doi:10.3357/asem.3789.2014. PMID 24479265.