Vacutainer

A vacutainer blood collection tube is a sterile glass or plastic test tube with a colored rubber stopper creating a vacuum seal inside of the tube, facilitating the drawing of a predetermined volume of liquid. Vacutainer tubes may contain additives designed to stabilize and preserve the specimen prior to analytical testing. Tubes are available with a safety-engineered stopper, with a variety of labeling options and draw volumes. The color of the top indicates the additives in the vial.[1]

Vacutainer tubes were invented by Joseph Kleiner in 1949.[2] Vacutainer is a registered trademark of Becton Dickinson, which manufactures and sells the tubes today.[3][4]

Principles

The Vacutainer needle is double-ended: the inner end is encased in a thin rubber coating that prevents blood from leaking out if the Vacutainer tubes are changed during a multi-draw, and the outer end which is inserted into the vein. When the needle is screwed into the translucent plastic needle holder, the coated end is inside the holder.

When a tube is inserted into the holder, its rubber cap is punctured by this inner needle and the vacuum in the tube pulls blood through the needle and into the tube. The filled tube is then removed and another can be inserted and filled the same way. The amount of air evacuated from the tube predetermines how much blood will fill the tube before blood stops flowing.

Each tube is topped with a color-coded plastic or rubber cap. Tubes often include additives that mix with the blood when collected, and the color of each tube's plastic cap indicates which additives it contains.

Blood collection tubes expire because over time the vacuum is lost and blood will not be drawn into the tube when the needle punctures the cap.

Types of tubes

Vacutainer tubes may contain additional substances that preserve blood for processing in a medical laboratory. Using the wrong tube may make the blood sample unusable for the intended purpose. These additives are typically thin film coatings applied using an ultrasonic nozzle.

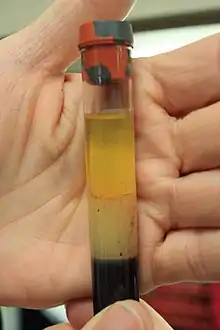

The additives may include anticoagulants (EDTA, sodium citrate, heparin) or a gel with density between those of blood cells and blood plasma. Additionally, some tubes contain additives that preserve certain components of or substances within the blood, such as glucose. When a tube is centrifuged, the materials within are separated by density, with the blood cells sinking to the bottom and the plasma or serum accumulating at the top. Tubes containing gel can be easily handled and transported after centrifugation without the blood cells and serum mixing.

The meanings of the various colors are standardized across manufacturers.[5][6][7]

The term order of draw refers to the sequence in which tubes should be filled. The needle which pierces the tubes can carry additives from one tube into the next, so the sequence is standardized so that any cross-contamination of additives will not affect laboratory results.[7]

| Tube cap color or type in order of draw | Additive | Usage and comments |

|---|---|---|

| Blood culture bottle | Sodium polyanethol sulfonate (anticoagulant) and growth media for microorganisms | Usually drawn first for minimal risk of contamination.[8] Two bottles are typically collected in one blood draw; one for aerobic organisms and one for anaerobic organisms.[9] |

| Light blue | Sodium citrate (anticoagulant) | Coagulation tests such as prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) and thrombin time (TT). Tube must be filled 100%. |

| Plain red | No additive | Serum: Total complement activity, cryoglobulins |

| Gold (sometimes red and grey "tiger top"[10]) | Clot activator and serum separating gel[11] | Serum-separating tube: Tube inversions promote clotting. Most chemistry, endocrine and serology tests, including hepatitis and HIV. |

| Dark green | Sodium heparin (anticoagulant) | Chromosome testing, HLA typing, ammonia, lactate |

| Light green | Lithium heparin (anticoagulant) | Plasma. Tube inversions prevent clotting |

| Lavender ("purple") | EDTA (chelator / anticoagulant) | Whole blood: CBC, ESR, Coombs test, platelet antibodies, flow cytometry, blood levels of tacrolimus and cyclosporin |

| Pink | EDTA (chelator / anticoagulant) | Blood typing and cross-matching, direct Coombs test, HIV viral load |

| Royal blue | EDTA (chelator / anticoagulant) | Trace elements, heavy metals, most drug levels, toxicology |

| Tan | EDTA (chelator / anticoagulant) | Lead |

| Gray |

|

Glucose, lactate[13] |

| Yellow | Acid-citrate-dextrose A (anticoagulant) | Tissue typing, DNA studies, HIV cultures |

| Pearl ("white") | Separating gel and (K2)EDTA | PCR for adenovirus, toxoplasma and HHV-6 |

History

.jpg.webp)

Vacutainer technology was developed in 1947 by Joseph Kleiner,[2] and is currently marketed by Becton Dickinson (B-D).[14] The Vacutainer was preceded by other vacuum-based phlebotomy technology such as the Keidel vacuum.

The plastic tube version, known as Vacutainer PLUS, was developed at B-D in the early 1990s by E. Vogler, D. Montgomery and G. Harper amongst others of the Surface Science Group as US patents 5344611, 5326535, 5320812, 5257633 and 5246666.[15]

Vacutainers are widely used in phlebotomy in developed countries due to safety and ease of use. Vacutainers have the advantage of being prepared with additives, allowing easy multi-tube draws, and having a lower chance of hemolysis.[16] In developing countries, it is still common to draw blood using a syringe or syringes.

References

- "Vacutainer and Their Use in Blood Sampling". medcaretips.com. 5 February 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Rosenfeld L (2000). "A golden age of clinical chemistry: 1948–1960". Clin Chem. 46 (10): 1705–14. doi:10.1093/clinchem/46.10.1705. PMID 11017957.

- "VACUTAINER - Trademark Details". Justia. Justia Corporate Center. 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- "BD Vacutainer®". BD. Becton Dickinson. 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- "Specimen Collection Tubes & Containers". Archived from the original on 2006-02-12. Retrieved 2006-02-01.

- "Quick Collection List". Archived from the original on 2005-12-16. Retrieved 2006-02-01.

- "Blood collection: routine venipuncture and specimen handling". Retrieved 2006-02-01.

- Pagana, KD; Pagana, TJ; Pagana, TN (19 September 2014). Mosby's Diagnostic and Laboratory Test Reference - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-323-22592-2.

- "Chapter 3.4.1: Blood cultures; general detection and interpretation". Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. Wiley. 6 August 2020. ISBN 978-1-55581-881-4.

- "Test Tube Guide and Order of Draw" (PDF). Guthrie Laboratory Services. June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Specimen requirements/containers". Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, UCI School of Medicine. Retrieved 2020-09-10.

- Castellini MA, Castellini JM, Kirby VL (1992). "Effects of standard anticoagulants and storage procedures on plasma glucose values in seals". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 201 (1): 145–8. PMID 1644639.

- Amitava Dasgupta; Jorge L. Sepulveda (20 July 2019). Accurate Results in the Clinical Laboratory: A Guide to Error Detection and Correction. Elsevier Science. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-12-813777-2.

- "BD Vacutainer Venous Blood Collection – Tube Guide" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- "US Patent Office Patent number search".

- Ames, A.C.; Bamford, E. (1975). "An Appraisal of the "Vacutainer" System for Blood Collection". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 12 (1–6): 151–55. doi:10.1177/000456327501200136. PMID 15637911.