Vaginal yeast infection

Vaginal yeast infection, also known as candidal vulvovaginitis and vaginal thrush, is excessive growth of yeast in the vagina that results in irritation.[5][1] The most common symptom is vaginal itching, which may be severe.[1] Other symptoms include burning with urination, a thick, white vaginal discharge that typically does not smell bad, pain during sex, and redness around the vagina.[1] Symptoms often worsen just before a woman's period.[2]

| Vaginal yeast infection | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Candidal vulvovaginitis, vaginal thrush |

| |

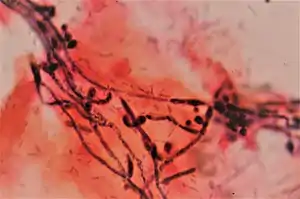

| Gram stain showing the spores and pseudohyphae of Candida albicans surrounded by round vaginal skin cells, in a case of candidal vulvovaginitis. | |

| Specialty | Gynaecology |

| Symptoms | Vaginal itching, burning with urination, white and thick vaginal discharge, pain with sex, redness around the vagina[1] |

| Causes | Excessive growth of Candida[1] |

| Risk factors | Antibiotics, pregnancy, diabetes, HIV/AIDS[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Testing the vaginal discharge[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Chlamydia, gonorrhea, bacterial vaginosis[3][1] |

| Treatment | Antifungal medication[4] |

| Frequency | 90% of women at some point[1] |

Vaginal yeast infections are due to excessive growth of Candida.[1] These yeast are normally present in the vagina in small numbers.[1] Vaginal yeast infections are typically caused by the yeast species Candida albicans. Candida albicans is a common fungus often harbored in the mouth, digestive tract, or vagina without causing adverse symptoms.[6] The causes of excessive Candida growth are not well understood,[7] but some predisposing factors have been identified.

It is not classified as a sexually transmitted infection; however, it may occur more often in those who are frequently sexually active.[1][2] Risk factors include taking antibiotics, pregnancy, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS.[2] Tight clothing, type of underwear, and personal hygiene do not appear to be factors.[2] Diagnosis is by testing a sample of vaginal discharge.[1] As symptoms are similar to that of the sexually transmitted infections, chlamydia and gonorrhea, testing may be recommended.[1]

Treatment is with an antifungal medication.[4] This may be either as a cream such as clotrimazole or with oral medications such as fluconazole.[4] Despite the lack of evidence, wearing cotton underwear and loose fitting clothing is often recommended as a preventive measure.[1][2] Avoiding douching and scented hygiene products is also recommended.[1] Probiotics have not been found to be useful for active infections.[8]

Around 75% of women have at least one vaginal yeast infection at some point in their lives, while nearly half have at least two.[1][9] Around 5% have more than three infections in a single year.[9] It is the second most common cause of vaginal inflammation after bacterial vaginosis.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of vaginal thrush include vulval itching, vulval soreness and irritation, pain or discomfort during sexual intercourse (superficial dyspareunia), pain or discomfort during urination (dysuria) and vaginal discharge, which is usually odourless.[10] Although the vaginal discharge associated with yeast infection is often described as thick and lumpy, like paper paste or cottage cheese, it can also be thin and watery, or thick and of uniform texture.[2] In one study, women with vaginal yeast infection were no more likely to describe their discharge as cottage-cheese like than women without.[11]

As well as the above symptoms of thrush, vulvovaginal inflammation can also be present. The signs of vulvovaginal inflammation include erythema (redness) of the vagina and vulva, vaginal fissuring (cracked skin), edema (swelling from a build-up of fluid), also in severe cases, satellite lesions (sores in the surrounding area). This is rare, but may indicate the presence of another fungal condition, or the herpes simplex virus (the virus that causes genital herpes).[12]

Vaginal candidiasis can very rarely cause congenital candidiasis in newborns.[13]

Causes

Medications

Infection occurs in about 30% of women who are taking a course of antibiotics by mouth.[2] Broad-spectrum antibiotics kill healthy bacteria in the vagina, such as Lactobacillus. These bacteria normally help to limit yeast colonization.[14][15]

Oral contraceptive use is also associated with increased risk of vaginal thrush.[16][2]

Pregnancy

In pregnancy, higher levels of estrogen make a woman more likely to develop a yeast infection. During pregnancy, the Candida fungus is more common, and recurrent infection is also more likely.[2] There is tentative evidence that treatment of asymptomatic candidal vulvovaginitis in pregnancy reduces the risk of preterm birth.[17]

Lifestyle

While infections may occur without sex, a high frequency of intercourse increases the risk.[2] Personal hygiene methods or tight-fitting clothing, such as tights and thong underwear, do not appear to increase the risk.[2]

Diseases

Those with poorly controlled diabetes have increased rates of infection while those with well controlled diabetes do not.[2] The risk of developing thrush is also increased when there is poor immune function,[12] as with HIV/AIDS, or in those receiving chemotherapy.

Species of yeast responsible

While Candida albicans is the most common yeast species associated with vaginal thrush, infection by other types of yeast can produce similar symptoms. A Hungarian study of 370 patients with confirmed vaginal yeast infections identified the following types of infection:[18]

- Candida albicans: 85.7%

- Non-albicans Candida (8 species): 13.2%

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae: 0.8%

- Candida albicans and Candida glabrata: 0.3%

Non-albicans Candida are often found in complicated cases of vaginal thrush in which the first line of treatment is ineffective. These cases are more likely in those who are immunocompromised.[19]

Diagnosis

Vulvovaginal candidosis is the presence of Candida in addition to vaginal inflammation.[3] The presence of yeast is typically diagnosed in one of three ways: vaginal wet mount microscopy, microbial culture, and antigen tests.[3] The results may be described as being either uncomplicated or complicated.

Uncomplicated

Uncomplicated thrush is when there are less than four episodes in a year, the symptoms are mild or moderate, it is likely caused by Candida albicans, and there are no significant host factors such as poor immune function.[20]

Complicated

Complicated thrush is four or more episodes of thrush in a year or when severe symptoms of vulvovaginal inflammation are experienced. It is also complicated if coupled with pregnancy, poorly controlled diabetes, poor immune function, or the thrush is not caused by Candida albicans.[20]

Recurrent

About 5-8% of the reproductive age female population will have four or more episodes of symptomatic Candida infection per year; this condition is called recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC).[21][22] Because vaginal and gut colonization with Candida is commonly seen in people with no recurrent symptoms, recurrent symptomatic infections are not simply due to the presence of Candida organisms. There is some support for the theory that RVVC results from an especially intense inflammatory reaction to colonization. Candida antigens can be presented to antigen-presenting cells, which may trigger cytokine production and activate lymphocytes and neutrophils that then cause inflammation and edema.[23][24]

Treatment

The following treatments are typically recommended:

- Intravaginal (vaginal suppository): butoconazole, clotrimazole, miconazole, nystatin, tioconazole, terconazole.[4] Candidal vulvovaginitis in pregnancy should be treated with intravaginal clotrimazole or nystatin for at least 7 days.[25] All are more or less equally effective.[26]

- By mouth: ibrexafungerp, fluconazole as a single dose.[4] For severe disease another dose after 3 days may be used.[26]

Short-course topical formulations (i.e., single dose and regimens of 1–3 days) effectively treat uncomplicated candidal vulvovaginitis. The topically applied azole drugs are more effective than nystatin. Treatment with azoles results in relief of symptoms and negative cultures in 80–90% of patients who complete therapy.[4]

The creams and suppositories in this regimen are oil-based and might weaken latex condoms and diaphragms. Treatment for vagina thrush using antifungal medication is ineffective in up to 20% of cases. Treatment for thrush is considered to have failed if the symptoms do not clear within 7–14 days. There are a number of reasons for treatment failure. For example, if the infection is a different kind, such as bacterial vaginosis (the most common cause of abnormal vaginal discharge), rather than thrush.[12]

Recurrent

For infrequent recurrences, the simplest and most cost-effective management is self-diagnosis and early initiation of topical therapy.[27] However, women whose condition has previously been diagnosed with candidal vulvovaginitis are not necessarily more likely to be able to diagnose themselves; therefore, any woman whose symptoms persist after using an over the counter preparation, or who has a recurrence of symptoms within two months, should be evaluated with office-based testing.[4] Unnecessary or inappropriate use of topical preparations is common and can lead to a delay in the treatment of other causes of vulvovaginitis, which can result in worse outcomes.[4]

When there are more than four recurrent episodes of candidal vulvovaginitis per year, a longer initial treatment course is recommended, such as orally administered fluconazole followed by a second and third dose 3 and 6 days later, respectively.[28]

Other treatments after more than four episodes per year, may include ten days of either oral or topical treatment followed by fluconazole orally once per week for six months.[26] About 10-15% of recurrent candidal vulvovaginitis cases are due to non-Candida albicans species.[29] Non-albicans species tend to have higher levels of resistance to fluconazole.[30] Therefore, recurrence or persistence of symptoms while on treatment indicates speciation and antifungal resistance tests to tailor antifungal treatment.[28]

Alternative medicine

Up to 40% of women seek alternatives to treat vaginal yeast infection.[31] Example products are herbal preparations, probiotics and vaginal acidifying agents.[31] Other alternative treatment approaches include switching contraceptive, treatment of the sexual partner and gentian violet.[31] However, the effectiveness of such treatments has not received much study.[31]

Probiotics (either as pills or as yogurt) do not appear to decrease the rate of occurrence of vaginal yeast infections.[32] No benefit has been found for active infections.[8] Example probiotics purported to treat and prevent candida infections are Lactobacillus fermentum RC-14, Lactobacillus fermentum B-54, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus acidophilus.[33]

There is no evidence to support the use of special cleansing diets and colonic hydrotherapy for prevention.

Epidemiology

The number of cases of vaginal yeast infection is not entirely clear because it is not a reportable disease and it is commonly diagnosed clinically without laboratory confirmation.[33]

Candidiasis is one of the three most common vaginal infections along with bacterial vaginosis and trichomonas.[3] About 75% of women have at least one infection in their lifetime,[2] 40%–45% will have two or more episodes,[20] and approximately 20% of women get an infection yearly.[3]

Research

Vaccines that target C. albicans are under active development since several years. Phase 2 results published in June 2018 showed a safe and high immunogenicity of the NDV-3A vaccine candidate.[34]

References

- "Vaginal yeast infections fact sheet". womenshealth.gov. December 23, 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Sobel, JD (9 June 2007). "Vulvovaginal candidosis". Lancet. 369 (9577): 1961–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60917-9. PMID 17560449. S2CID 33894309.

- Ilkit, M; Guzel, AB (August 2011). "The epidemiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidosis: a mycological perspective". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 37 (3): 250–61. doi:10.3109/1040841X.2011.576332. PMID 21599498. S2CID 19328371.

- Workowski KA, Berman SM (August 2006). "Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006". MMWR Recomm Rep. 55 (RR-11): 1–94. PMID 16888612. Archived from the original on 2014-10-20.

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 309. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- "Vaginal yeast infection". MedlinePlus. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Watson, C. J.; Grando, D.; Garland, S. M.; Myers, S.; Fairley, C. K.; Pirotta, M. (26 July 2012). "Premenstrual vaginal colonization of Candida and symptoms of vaginitis". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 61 (Pt 11): 1580–1583. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.044578-0. PMID 22837219.

- Abad, CL; Safdar, N (June 2009). "The role of lactobacillus probiotics in the treatment or prevention of urogenital infections – a systematic review". Journal of Chemotherapy (Florence, Italy). 21 (3): 243–52. doi:10.1179/joc.2009.21.3.243. PMID 19567343. S2CID 32398416.

- Egan ME, Lipsky MS (September 2000). "Diagnosis of vaginitis". Am Fam Physician. 62 (5): 1095–104. PMID 10997533. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

- Mendling W, Brasch J (2012). "Guideline vulvovaginal candidosis (2010) of the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics, the Working Group for Infections and Infectimmunology in Gynecology and Obstetrics, the German Society of Dermatology, the Board of German Dermatologists and the German Speaking Mycological Society". Mycoses. 55 Suppl 3: 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02185.x. PMID 22519657. S2CID 35082539.

- Gunter, Jen (27 August 2019). The vagina bible : the vulva and the vagina-- separating the myth from the medicine. London. ISBN 978-0-349-42175-9. OCLC 1119529898.

- "Thrush in men and women". nhs.uk. 2018-01-09. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- Skoczylas, MM; Walat, A; Kordek, A; Loniewska, B; Rudnicki, J; Maleszka, R; Torbé, A (2014). "Congenital candidiasis as a subject of research in medicine and human ecology". Annals of Parasitology. 60 (3): 179–89. PMID 25281815.

- "Yeast infection (vaginal)". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Sobel JD (March 1992). "Pathogenesis and treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". Clin. Infect. Dis. 14 Suppl 1: S148–53. doi:10.1093/clinids/14.Supplement_1.S148. PMID 1562688.

- "Vaginal Candidiasis | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2020-11-10. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- Roberts, CL; Algert, CS; Rickard, KL; Morris, JM (21 March 2015). "Treatment of vaginal candidiasis for the prevention of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Systematic Reviews. 4: 31. doi:10.1186/s13643-015-0018-2. PMC 4373465. PMID 25874659.

- Nemes-Nikodém, Éva; Tamási, Béla; Mihalik, Noémi; Ostorházi, Eszter (1 January 2015). "Vulvovaginitis candidosában előforduló sarjadzógomba-speciesek" [Yeast species in vulvovaginitis candidosa]. Orvosi Hetilap (in Hungarian). 156 (1): 28–31. doi:10.1556/OH.2015.30081. PMID 25544052.

- Sobel, Jack. "Vulvovaginal Candidiasis". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- "Vulvovaginal Candidiasis - 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines". www.cdc.gov. 2019-01-11. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- Obel JD (1985). "Epidemiology and pathogen- esis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 152 (7 (Pt 2)): 924–35. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(85)80003-X. PMID 3895958.

- Spinillo A, Pizzoli G, Colonna L, Nicola S, De Seta F, Guaschino S (1993). "Epidemiologic characteristics of women with idiopathic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". Obstet Gynecol. 81 (5 (Pt 1)): 721–7. PMID 8469460.

- Fidel PL Jr; Sobel JD (1996). "Immunopathogen- esis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". Clin Microbiol Rev. 9 (3): 335–48. doi:10.1128/CMR.9.3.335. PMC 172897. PMID 8809464.

- Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, Danna P, Hooton TM, Rompalo A, Sperling M, Livengood C, Horowitz B, Von Thron J, Edwards L, Panzer H, Chu TC (August 2004). "Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (9): 876–83. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa033114. PMID 15329425.

- Ratcliffe, Stephen D.; Baxley, Elizabeth G.; Cline, Matthew K. (2008). Family Medicine Obstetrics. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 273. ISBN 978-0323043069. Archived from the original on 2016-08-21.

- Pappas, PG; Kauffman, CA; Andes, DR; Clancy, CJ; Marr, KA; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L; Reboli, AC; Schuster, MG; Vazquez, JA; Walsh, TJ; Zaoutis, TE; Sobel, JD (16 December 2015). "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 62 (4): e1-50. doi:10.1093/cid/civ933. PMC 4725385. PMID 26679628.

- Ringdahl, EN (Jun 1, 2000). "Treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". American Family Physician. 61 (11): 3306–12, 3317. PMID 10865926.

- Ramsay, Sarah; Astill, Natasha; Shankland, Gillian; Winter, Andrew (November 2009). "Practical management of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". Trends in Urology, Gynaecology & Sexual Health. 14 (6): 18–22. doi:10.1002/tre.127.

- Sobel, JD (2003). "Management of patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". Drugs. 63 (11): 1059–66. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363110-00002. PMID 12749733. S2CID 28796898.

- Sobel, JD (1988). "Pathogenesis and epidemiology of vulvovaginal candidiasis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 544 (1): 547–57. Bibcode:1988NYASA.544..547S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb40450.x. PMID 3063184. S2CID 33857719.

- Cooke G, Watson C, Smith J, Pirotta M, van Driel ML (2011). "Treatment for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (thrush) (Protocol)" (PDF). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD009151. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009151. S2CID 58058861.

- Jurden, L; Buchanan, M; Kelsberg, G; Safranek, S (June 2012). "Clinical inquiries. Can probiotics safely prevent recurrent vaginitis?". The Journal of Family Practice. 61 (6): 357, 368. PMID 22670239.

- Xie HY, Feng D, Wei DM, Mei L, Chen H, Wang X, Fang F (November 2017). "Probiotics for vulvovaginal candidiasis in non-pregnant women". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 (11): CD010496. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010496.pub2. PMC 6486023. PMID 29168557.

- Edwards Jr, J. E.; Schwartz, M. M.; Schmidt, C. S.; Sobel, J. D.; Nyirjesy, P.; Schodel, F.; Marchus, E.; Lizakowski, M.; Demontigny, E. A.; Hoeg, J.; Holmberg, T.; Cooke, M. T.; Hoover, K.; Edwards, L.; Jacobs, M.; Sussman, S.; Augenbraun, M.; Drusano, M.; Yeaman, M. R.; Ibrahim, A. S.; Filler, S. G.; Hennessey Jr, J. P. (2018-06-01). "A Fungal Immunotherapeutic Vaccine (NDV-3A) for Treatment of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis-A Phase 2 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial". Clinical Infectious Diseases. PubMed.gov. 66 (12): 1928–1936. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy185. PMC 5982716. PMID 29697768.