Woolly hair

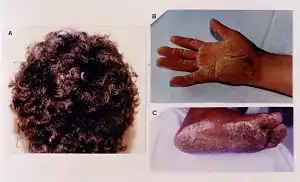

Woolly hair is a difficult to brush hair, usually present since birth and typically most severe in childhood.[1] It has extreme curls and kinks and occurs in non-black people.[3] The hairs come together to form tight locks, unlike in afro-textured hair, where the hairs remain individual.[1] Woolly hair can be generalised over the whole scalp, when it tends to run in families, or it may involve just part of the scalp as in woolly hair nevus.[2]

| Woolly hair | |

|---|---|

| |

| Woolly hair and other symptoms of Naxos syndrome | |

| Symptoms | Hair: difficult to brush, tight locks, short, lighter colour[1] |

| Usual onset | Birth, infancy[1] |

| Types | Familial, hereditary, woolly hair nevus[2] |

| Risk factors | May run in families[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Microscopy, trichoscopy, dermoscopy, electron microscopy[2] |

| Prognosis | May improve with age[1] |

| Frequency | Rare[1] |

The presence of woolly hair may indicate other problems such as with the heart in Naxos–Carvajal syndrome.[4] Diagnosis is suspected by its general appearance and confirmed by scanning electron microscopy.[5]

The condition is rare.[1] Alfred Milne Gossage coined the term woolly hair in 1908.[6][7] Edgar Anderson distinguished woolly hair from afro-textured hair in 1936.[8]

Discovery

Alfred Milne Gossage coined the term woolly hair to describe the sign in 18 members in three or four generations of a European family in Lowestoft, England, in 1908.[6][7] He thought it resembled afro-textured hair, possibly from a Mexican ancestor in that family.[7] He described a dominant inheritance in several members with thick skin of palms and soles, curly hair, and two different coloured eyes, and sent them to William Bateson.[9] Edgar Anderson distinguished woolly hair from Afro-hair in 1936.[8] In 1974 Hutchinson's team classified woolly hair as hereditary woolly hair (autosomal dominant), familial woolly hair (autosomal recessive), and woolly hair nevus.[2] Woolly hair was found in Naxos syndrome, first described in 1986 in Naxos, Greece, and was noted in Carvajal syndrome, first described in 1998, in Ecuador.[4]

Cause

Woolly hair may run in families and either occur on its own, or as part of a syndrome.[4]

Hereditary woolly hair

Hereditary woolly hair is autosomal dominant.[2]

Familial woolly hair

Familial woolly hair is autosomal recessive.[2] It may be part of a syndrome such as Naxos syndrome, due to passing on of mutations in the JUP gene.[4] When part of Carvajal syndrome, it is due the passing of mutations of the Desmoplakin gene.[4] The two syndromes caused by two different genes, are considered as one entity; Naxos–Carvajal syndrome.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Woolly hair is typically very curly, kinky and characteristically impossible to brush.[1][3] It can be generalised over the whole scalp, or involve just part of the scalp, and occurs in non-black people.[1][3] The hairs come together to form tight locks, whereas in afro-textured hair the hairs remain individual.[1] The hairs typically remain shorter than 12 centimetres (4.7 in) and may be slightly lighter in colour.[1][2]

Woolly hair nevus is a localised area of woolly hair, which may occur on its own, or appear as dark twisted and kinking hair in an adult.[2] Half of people with woolly hair nevus have a warty skin lesion on the same side of the body.[2] It may be associated with eye problems such as two different coloured eyes or strands of tissue across the pupil of the eye.[2] Other associations include ear problems, kidney disease, tooth decay, impairment of bone growth, and skin lesions.[2]

Generalised woolly hair is typically seen in Naxos–Carvajal syndrome (with heart involvement),[4] Noonan syndrome, and cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome.[2][4]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is suspected by its general appearance and confirmed by scanning electron microscopy.[5] Microscopy, trichoscopy and dermoscopy also play a role.[2] The hair strand typically has a smaller diameter, is ovoid on cross-section and exhibits abnormal twisting.[1][2] The hair shaft also has weak points and alternating dark and light bands.[1] The hair shaft is characteristically of a "snake crawl appearance".[2] Dermoscopy may be required to recognise skin signs.[2]

Outcome

The condition may improve in adulthood.[1]

Epidemiology

The condition is rare.[1]

See also

References

- James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "33. Diseases of the skin appendages". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. p. 767. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6.

- Gomes, Tiago Fernandes; Guiote, Victoria; Henrique, Martinha (15 January 2020). "Woolly hair nevus: case report and review of literature". Dermatology Online Journal. 26 (1): Article 7. doi:10.5070/D3261047188. ISSN 1087-2108. PMID 32155026.

- Pavone, Piero; Falsaperla, Raffaele; Barbagallo, Massimo; Polizzi, Agata; Praticò, Andrea D.; Ruggieri, Martino (2 November 2017). "Clinical spectrum of woolly hair: indications for cerebral involvement". Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 43 (1): 99. doi:10.1186/s13052-017-0417-1. ISSN 1824-7288. PMC 5667512. PMID 29096685.

- Hernandez-Martin, Angela; Tamariz-Martel, Amalia (2021). "8. Cardiocutaneous desmosomal disorders". In Salavastru, Carmen; Murrell, Dedee F.; Otton, James (eds.). Skin and the Heart. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 114–116. ISBN 978-3-030-54778-3.

- Swamy, SuchethaSubba; Ravikumar, Bc; Vinay, Kn; Yashovardhana, Dp; Aggarwal, Archit (2017). "Uncombable hair syndrome with a woolly hair nevus". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 83 (1): 87–88. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.191133. PMID 27679409. S2CID 3204525.

- Orfanos, Constantin E.; Happle, Rudolf (2012). Hair and Hair Diseases. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-74614-7.

- Gates, Reginald Ruggles (1948). Human Genetics. Macmillan. p. 1355.

- McKusick, Victor Almon (1971). Mendelian Inheritance in Man: Catalogs of Autosomal Dominant, Autosomal Recessive, and X-linked Phenotypes. Johns Hopkins Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-8018-1296-5.

- Rushton, Alan R. (2017). "Bateson and the doctors: the introduction of Mendelian genetics to the British medical community 1900–1910". In Petermann, Heike I.; Harper, Peter S.; Doetz, Susanne (eds.). History of Human Genetics: Aspects of Its Development and Global Perspectives. Springer. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-319-51782-7.

Further reading

- Gossage, A. M. (April 1908). "The inheritance of certain human abnormalities". QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. Old Series. 1 (3): 331–347. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.qjmed.a069191.

- Anderson, Edgar (1 November 1936). "An American pedigree for woolly hair". Journal of Heredity. 27 (11): 444. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a104158. ISSN 0022-1503.

- Davenport, Charles Benedict (1912). Heredity in relation to eugenics. London: London : Williams & Norgate. p. 138.