1968 Illinois earthquake

The 1968 Illinois earthquake (a New Madrid event)[4] was the largest recorded earthquake in the U.S. Midwestern state of Illinois. Striking at 11:02 am on November 9, it measured 5.4 on the Richter scale.[5] Although no fatalities occurred, the event caused considerable structural damage to buildings, including the toppling of chimneys and shaking in Chicago, the region's largest city. The earthquake was one of the most widely felt in U.S. history, largely affecting 23 states over an area of 580,000 sq mi (1,500,000 km2). In studying its cause, scientists discovered the Cottage Grove Fault in the Southern Illinois Basin.

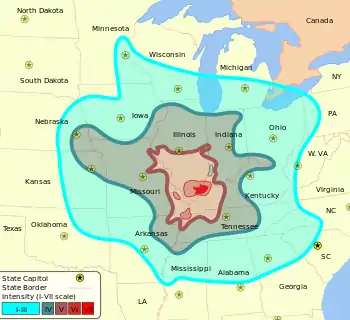

Isoseismal map for the event (I–III are Not felt to Weak, IV is Light, V is Moderate, VI is Strong, VII is Very strong) | |

| UTC time | 1968-11-09 17:01:38 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 814965 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | November 9, 1968 |

| Local time | 11:01:40 CST |

| Magnitude | 5.3 mb[1] |

| Depth | 19 km (12 mi)[2] |

| Epicenter | 37.95°N 88.48°W[3] |

| Type | Dip-slip |

| Max. intensity | VII (Very strong) |

| Casualties | None |

Within the region, millions felt the rupture. Reactions to the earthquake varied; some people near the epicenter did not react to the shaking, while others panicked. A future earthquake in the region is extremely likely; in 2005, seismologists and geologists estimated a 90% chance of a magnitude 6–7 tremor before 2055, likely originating in the Wabash Valley seismic zone on the Illinois–Indiana border or the New Madrid fault zone.

Background

The first recorded earthquake in Illinois is from 1795 when a small earthquake shook the frontier settlement of Kaskaskia, although the epicenter could not be located and may have been outside Illinois.[6] Data from large earthquakes—in May and July 1909, and November 1968—suggest that earthquakes in the area are of moderate magnitude but can be felt over a large geographical area, largely because of the lack of fault lines. The May 1909 Aurora earthquake affected people in an area of 500,000 sq mi (1,300,000 km2);[6] the 1968 Illinois earthquake was felt by those living in an area of about 580,000 sq mi (1,500,000 km2).[6] Contradicting the idea that the region's earthquakes are felt over a wide area, a 1965 shock was only noticed near Tamms, though it had the same intensity level (VII) as those of 1909 and 1968.[6] Before 1968, earthquakes had been recorded in 1838, 1857, 1876,[a] 1881, 1882, 1883, 1887, 1891, 1903, 1905, 1912, 1917, 1922,[b] 1934, 1939, 1947, 1953, 1955, and 1958.[6] Since 1968, other earthquakes have occurred in the same region in 1972, 1974, 1984, and 2008.[6][7]

Geology

The quake struck on Saturday, November 9, 1968, at 11:02 am.[8] The quake's epicenter was slightly northwest of Broughton in Hamilton County,[9] and close to the Illinois–Indiana border, about 120 miles (190 km) east of St. Louis, Missouri.[10] Surrounding the epicenter were several small towns built on flat glacial lake plains and low hills.[11] Scientists described the rupture as "strong".[10] During the quake, surface wave and body wave magnitudes were measured at 5.2 and 5.54, respectively.[3] The magnitude of the quake reached 5.4 on the Richter scale.[5] The earthquake occurred at a depth of 25 km (16 mi).[12][c]

A fault plane solution for the earthquake confirmed two nodal planes (one is always a fault plane, the other an auxiliary plane) striking north–south and dipping about 45° to the east and to the west. This faulting suggests dip slip reverse motion and a horizontal east–west axis of confining stress.[3] At the time of the earthquake, no faults were known in the immediate epicentral region (see below), but the motion corresponded to movement along the Wabash Valley Fault System roughly 10 mi (16 km) east of the region.[3] The rupture also partly occurred on the New Madrid Fault, responsible for the great New Madrid earthquakes in 1812. The New Madrid tremors were the most powerful earthquakes to hit the contiguous United States.[13]

Various theories were put forward for the cause of the rupture. Donald Roll, director of seismology at Loyola University Chicago, proposed that the quake was caused by massive amounts of silt being deposited by rivers, generating a "seesaw" effect on the plates beneath. "The weight of the silt depressed one end of the block and tipped up the other," he said.[14] Scientists eventually realized, though, that the cause was a then-unknown fault, the Cottage Grove Fault, a small tear in the Earth's rock in the Southern Illinois Basin near the city of Harrisburg, Illinois.

The fault, which is aligned east–west, is connected to the north–south-trending Wabash Valley Fault System at its eastern end.[15] Seismographic mapping completed by geologists revealed monoclines, anticlines, and synclines, all of which suggest deformation during the Paleozoic era, when strike-slip faulting took place nearby.[16] The fault runs along an ancient Precambrian terrane boundary. It was active mainly in the Late Pennsylvanian and Early Permian epochs around 300 million years ago.[17]

Damage

The earthquake was felt in 23 states and affected a zone of 580,000 sq mi (1,500,000 km2). The shaking extended east to Pennsylvania and West Virginia, south to Mississippi and Alabama, north to Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and west to Oklahoma.[13] Isolated reports were received from Boston, Mobile, Alabama, Pensacola, Florida, southern Ontario,[18] Arkansas, Minnesota, Tennessee, Georgia, Kansas, Ohio, Mississippi, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Missouri, West Virginia, Alabama, Nebraska, Iowa, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, presumably because of shaking.[14] The worst-affected areas were in the general area of Evansville, Indiana, St. Louis, and Chicago, but with no major damage.[11] No deaths happened; the worst injury was a child knocked unconscious by falling debris outside his home.[13]

Damage was confined to Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and south-central Iowa,[18] and largely consisted of fallen chimneys, foundation cracks, collapsed parapets, and overturned tombstones. In one home in Dale, Illinois, near Tuckers Corners and southwest of McLeansboro, the quake cracked interior walls, plaster, and chimneys.[9] Using a type of victim study, the local post office surveyed residents and implemented a field inspection, which indicated the strongest shaking (MM VII) took place in the Wabash Valley, Ohio Valley, and other nearby south-central Illinois lowlands.[11] Outside this four-state zone, oscillating objects, including cars, chimneys, and the Gateway Arch, were reported to authorities.[11][13]

McLeansboro in particular experienced minor damage over an extensive area. Its local high school reported 19 broken windows in the girls' gymnasium, along with cracked plaster walls. Most of the high school's classrooms sustained fractured walls. The façade of the town's First United Methodist Church was damaged, and a brick and concrete block fell off the top. The Hamilton County Courthouse withstood several structural cracks, including one on the ceiling above the judge's seat. The town's residents also reported collapsing chimneys; three chimneys toppled at one home, leading to further damage.[19]

Most of the buildings that experienced chimney damage were 30 to 50 years old. The City Building in Henderson, Kentucky, 50 miles (80 km) east-southeast of the epicenter, sustained considerable structural damage. Moderate damage—including broken chimneys and fractured walls—occurred in towns in south-central Illinois, southwest Indiana, and northwest Kentucky. For instance, a concrete-brick cistern caved in 6.2 miles (10.0 km) west of Dale.[20]

In Lineville, Iowa, about 80 mi (130 km) south of Des Moines on the Missouri border, the quake was felt as a long shaking. The quake damaged the town's water tower, which began to leak 300 US gal (1,100 L) of water an hour.[21]

Donald Roll correctly predicted the earthquake would have no aftershocks. He later said, "That was kind of a safety valve. The pressure [that] has been built up has been released." He also described the earthquake as "a very rare occurrence".[14]

Response

Millions in the area experienced the earthquake, the first major seismic event in decades. Following the tremor, businesses in the area emptied. Many residents did not believe that the earthquake was over magnitude 5. Others did not realize an earthquake was taking place, for example, some residents thought their furnaces had exploded,[19] and one man thought that the shaking was caused by his son "jumping up and down".[22] At the Suntone Factory in McLeansboro, 30 mi (48 km) from the epicenter, workers rushed out of the building, thinking a 1,100 US gal (4,200 L) water tank inside had fallen.[22]

People's reactions varied; some described themselves as "shocked"; others admitted to being "shaky" or nervous for the rest of the day. Harold Kittinger, a worker at the Suntone Factory, said, "I do not care to tell anyone I was frightened. But I was not shaking in my shoes. My shoes were moving."[22] One woman hypothesized that the shaking was a "bomb".[22] Grace Standerfer suggested the earthquake was sudden, saying, "I was just scared to death. My husband and I were in the house. The Venetian shades began to shake one way, then another. When that awful blast came, he grabbed me and we ran outside. Things were falling and breaking in the house. I said to him, 'This is it.' I thought the world had come to an end. Outside, wires were moving. There was no wind. The ground was quivering under our feet. I was so scared. I did not know I was scared."[22] People in the community of Mount Vernon, Illinois, were frightened by the shaking. However, some did not notice the earthquake; Jane Bessen said her party was "in a car ... to Evansville and didn't know about it until we got there".[22]

Future threats

In 2005, scientists determined that a 90% probability existed of a magnitude 6–7 earthquake occurring in the New Madrid area during the next 50 years.[23] This could cause potentially high damage in the Chicago metropolitan area, which has a population near 10 million people. Pressure on the fault where the 1811–1812 Madrid earthquakes occurred was believed to be increasing,[23] but a later study by Eric Calais of Purdue University and other experts concluded the land adjacent to the New Madrid fault was moving less than 0.2 mm (0.0079 in) a year, increasing the span between expected earthquakes on the fault to 500–1,000 years.[24] Scientists anticipating a future earthquake suggest the Wabash Valley Fault as a possible source, calling it "dangerous".[25]

Douglas Wiens, a professor of earth and planetary sciences, reported: "The strongest earthquakes in the last few years have come from the Wabash Valley Fault",[25] and said the fault needs more scientific observation. Steven Obermeir of the United States Geological Survey is one of several scientists who have found sediments suggesting Wabash Valley Fault earthquakes around magnitude 7 on the Richter scale.[25] Michael Wyssession, an associate professor of earth and planetary sciences, denigrated the Madrid fault zone and said, "in 20 years there have been three magnitude 5 or better earthquakes on the Wabash Valley Fault. There is evidence that sometime in the past, the Wabash Valley Fault has produced as strong as magnitude 7 earthquakes. On the other hand, the New Madrid Fault has been very quiet for a long time now. Clearly, the Wabash Valley Fault has gotten our deserved attention."[25]

See also

- List of earthquakes in 1968

- List of earthquakes in Illinois

Notes

References

- International Seismological Centre. Event Bibliography. Thatcham, United Kingdom. [Event 814965].

- ISC-EB Event 814965 [IRIS]

- Stauder, William; Nuttli, Otto W. (1 June 1970). "Seismic studies: South central Illinois earthquake of November 9, 1968". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 60 (3): 973–981. Bibcode:1970BuSSA..60..973S. doi:10.1785/BSSA0600030973. S2CID 130306348.

- Hough 2002, p. 209.

- "Illinois Earthquake Information". United States Geological Survey. July 16, 2008. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- "Illinois: Earthquake History". United States Geological Survey. January 30, 2009. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- "Wisconsin: Earthquake History". United States Geological Survey. January 30, 2009. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- Blanchard, Robert (November 11, 1968). "Quake-Shy St. Louisans Compose Jangled Nerves". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- "It's Official-County was Center of Earthquake". McLeansboro Times-Leader. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- "22 States Struck By Strong Quake; Wide Area From Minnesota to Carolina Hit by Tremor" (PDF). New York Times. Associated Press. October 10, 1968. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- Gordon, David W.; Bennett, Theron J.; Herrmann, Robert B.; Rogers, Albert M. (1 June 1970). "The south-central Illinois earthquake of November 9, 1968: Macroseismic studies". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 60 (3): 953–971. Bibcode:1970BuSSA..60..953G. doi:10.1785/BSSA0600030953. S2CID 129609627. Retrieved November 14, 2008. (See this bulletin on the webpage of Earthquake Center of Saint Louis University)

- Kim, Won-Young (2003). "The 18 June 2002 Caborn, Indiana, Earthquake: Reactivation of Ancient Rift in the Wabash Valley Seismic Zone?". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 93 (5): 2201–2211. Bibcode:2003BuSSA..93.2201K. doi:10.1785/0120020223. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- Staff (November 10, 1968). "Quake Damage Minor; Felt Over Wide Area in Midwest and East". St. Louis Post Dispatch. p. 1A. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- "No Further Tremors Foreseen Following Quakes in 22 States" (PDF). New York Times. November 11, 1968. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- Bristol, Hubert M.; Treworgy, Janis D. (1979). The Wabash Valley fault System in Southeastern Illinois (PDF) (Report). Circular 509. Urbana, Illinois: Illinois Institute of Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- "Seismic Reflection Investigation of the Cottage Grove Fault System, Southern Illinois Basin". Geological Society of America. April 4, 2002. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- Duchek, Amanda B.; McBride, John H.; Nelson, W. John; Leetaru, Hannes E. (2004). "The Cottage Grove fault system (Illinois Basin): Late Paleozoic transpression along a Precambrian crustal boundary". GSA Bulletin. 116 (11–12): 1465–1484. Bibcode:2004GSAB..116.1465D. doi:10.1130/B25413.1.

- "Today in Earthquake History: November 9". United States Geological Survey. July 16, 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-04-22. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- "Earthquake Damage Probable at 90% of county Buildings". McLeansboro Times Leader. November 14, 1968. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- "Historic Earthquakes:Southern Illinois". United States Geological Survey. November 14, 1968. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- Times-Republican Newspaper; Corydon, Iowa; November 14, 1968

- "Some Took Quake Calmly, Others Shook For Hours". McLeansboro Times-Leader. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- Robert Roy Britt (June 22, 2005). "New Data Confirms Strong Earthquake Risk to Central U.S." LiveScience. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- "New Madrid Fault System, U.S., May Be Shutting Down". ScienceDaily. March 20, 2009. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- "Earthquake In Illinois Could Portend An Emerging Threat". ScienceDaily. April 25, 2008. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

Further reading

- Hough, Susan Elizabeth (2002). Earthshaking Science: What We Know (and Don't Know) About Earthquakes. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05010-2. OCLC 47831440.