1970 Bhola cyclone

The 1970 Bhola cyclone (Also known as the Great Cyclone of 1970[1]) was a devastating tropical cyclone that struck East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) and India's West Bengal on November 11, 1970. It remains the deadliest tropical cyclone ever recorded and one of the world's deadliest natural disasters. At least 300,000 people lost their lives in the storm,[2] possibly as many as 500,000,[3][4] primarily as a result of the storm surge that flooded much of the low-lying islands of the Ganges Delta.[5] Bhola was the sixth and strongest cyclonic storm of the 1970 North Indian Ocean cyclone season.[6]

| Extremely severe cyclonic storm (IMD scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

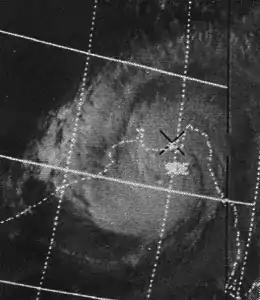

The ITOS 1 weather satellite image of the cyclone shortly after peak intensity making landfall in East Pakistan on November 12 | |

| Formed | November 8, 1970 |

| Dissipated | November 13, 1970 |

| Highest winds | 3-minute sustained: 185 km/h (115 mph) 1-minute sustained: 240 km/h (150 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 960 hPa (mbar); 28.35 inHg |

| Fatalities | 300,000–500,000 (Deadliest tropical cyclone on record) |

| Damage | $86.4 million (1970 USD) |

| Areas affected | East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) and India |

| Part of the 1970 North Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

The cyclone formed over the central Bay of Bengal on November 8 and traveled northward, intensifying as it did so. It reached its peak with winds of 185 km/h (115 mph) on November 10, and made landfall on the coast of East Pakistan on the following afternoon. The storm surge devastated many of the offshore islands, wiping out villages and destroying crops throughout the region. In the most severely affected Upazila, Tazumuddin, over 45% of the population of 167,000 was killed by the storm.

The Pakistani government, led by junta leader General Yahya Khan, was criticized for its delayed handling of relief operations following the storm, both by local political leaders in East Pakistan and by the international media. During the election that took place a month later, the opposition Awami League gained a landslide victory in the province, and continuing unrest between East Pakistan and the central government triggered the Bangladesh Liberation War, which led to 1971 Bangladesh genocide and eventually concluded with the creation of the independent country of Bangladesh.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On November 1, Tropical Storm Nora developed over the South China Sea, in the West Pacific Ocean. The system lasted for four days, before degenerating into a remnant low over the Gulf of Thailand on November 4, and subsequently moved west over the Malay Peninsula on November 5, 1970.[7][8] The remnants of this system contributed to the development of a new depression in the central Bay of Bengal on the morning of November 8. The depression intensified as it moved slowly northward, and the India Meteorological Department upgraded it to a cyclonic storm the next day. No country in the region had ever named tropical cyclones during this time, so no new identity was given.[9] The storm became nearly stationary that evening near 14.5° N, 87° E, but began to accelerate toward the north on November 10.[9]

The storm further intensified into a severe cyclonic storm on November 11 and began to turn towards the northeast, as it approached the head of the bay. It developed a clear eye and reached its peak intensity later that day, with three-minute sustained winds of 185 km/h (115 mph), one-minute sustained winds of 240 km/h (150 mph),[10] and a central pressure of 960 hPa. The cyclone made landfall on the East Pakistan coastline during the evening of November 12, around the same time as the local high tide. Once over land, the system began to weaken; the storm degraded to a cyclonic storm on November 13, when it was about 100 km (62 mi) south-southeast of Agartala. The storm then rapidly weakened into a remnant low over southern Assam that evening.[9]

Preparations

There is question as to how much of the information about the cyclone said to have been received by Indian weather authorities was transmitted to East Pakistan authorities. This is because the Indian and East Pakistani weather services may not have shared information given the Indo-Pakistani friction at the time.[11] A large part of the population was reportedly taken by surprise by the storm.[12] There were indications that East Pakistan's storm warning system was not used properly, which probably cost tens of thousands of lives.[13] The Pakistan Meteorological Department issued a report calling for "danger preparedness" in the vulnerable coastal regions during the day on November 12. As the storm neared the coast, a "great danger signal" was broadcast on Radio Pakistan. Survivors later said that this meant little to them, but that they had recognised a No. 1 warning signal as representing the greatest possible threat.[14]

Following two previously destructive cyclones in October 1960 which killed at least 16,000 people in East Pakistan,[15] the Pakistani central government contacted the American government for assistance in developing a system to avert future disasters. Gordon Dunn, the director of the National Hurricane Center at the time, carried out a detailed study and submitted his report in 1961. However, the central government did not carry out all of the recommendations Dunn had listed.[11]

Impact

Although the North Indian Ocean is the least active of the tropical cyclone basins, the coast of the Bay of Bengal is particularly vulnerable to the effects of tropical cyclones. The exact death toll from the Bhola cyclone will never be known, but at least 300,000 fatalities were associated with the storm,[2][8] possibly as many as 500,000.[3] The cyclone was not the most powerful of these, however; the 1991 Bangladesh cyclone was significantly stronger when it made landfall in the same general area, as a Category 5-equivalent cyclone with 260 km/h (160 mph) winds.

The Bhola cyclone is the deadliest tropical cyclone on record and also one of the deadliest natural disasters in modern history. A comparable number of people died as a result of the 1976 Tangshan earthquake, 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and the 2010 Haiti earthquake, but because of uncertainty in the number of deaths in all four disasters it may never be known which one was the deadliest.[16]

Bangladesh

| Rank | Name/Year | Region | Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bhola 1970 | Bangladesh | 300,000 |

| 2 | Bangladesh 1991 | Bangladesh | 138,866 |

| 3 | Nargis 2008 | Myanmar | 138,373 |

| 4 | Unnamed 1911 | Bangladesh | 120,000 |

| 5 | Unnamed 1917 | Bangladesh | 70,000 |

| 6 | Harriet 1962 | Thailand, Bangladesh | 50,935 |

| 7 | Unnamed 1919 | Bangladesh | 40,000 |

| 8 | Unnamed 1917 | Bangladesh | 70,000 |

| 9 | Nina 1975 | China | 26,000 |

| 10 | Unnamed 1958 | Bangladesh | 12,000 |

| Unnamed 1965 | Bangladesh | ||

The meteorological station in Chittagong, 95 km (59 mi) to the east of where the storm made landfall, recorded winds of 144 km/h (89 mph) before its anemometer was blown off at about 2200 UTC on November 12. A ship anchored in the port in the same area recorded a peak gust of 222 km/h (138 mph) about 45 minutes later.[8] As the storm made landfall, it caused a 10-metre (33 ft) high storm surge at the Ganges Delta.[19] In the port at Chittagong, the storm tide peaked at about 4 m (13 ft) above the average sea level, 1.2 m (3.9 ft) of which was the storm surge.[8]

Radio Pakistan reported that there were no survivors on the thirteen islands near Chittagong. A flight over the area showed the devastation was complete throughout the southern half of Bhola Island, and the rice crops of Bhola Island, Hatia Island and the nearby mainland coastline were destroyed.[20] Several seagoing vessels in the ports of Chittagong and Mongla were reported damaged, and the airports at Chittagong and Cox's Bazar were under 1 m (3.3 ft) of water for several hours.[21]

Over 3.6 million people were directly affected by the cyclone, and the total damage from the storm was estimated at US$86.4 million (US$450 million in 2006 dollars).[22] The survivors claimed that approximately 85% of homes in the area were destroyed or severely damaged, with the greatest destruction occurring along the coast.[23] Ninety percent of marine fishermen in the region suffered heavy losses, including the destruction of 9,000 offshore fishing boats. Of the 77,000 onshore fishermen, 46,000 were killed by the cyclone, and 40% of the survivors were affected severely. In total, approximately 65% of the fishing capacity of the coastal region was destroyed by the storm, in a region where about 80% of the protein consumed comes from fish. Agricultural damage was similarly severe with the loss of US$63 million worth of crops and 280,000 cattle.[8] Three months after the storm, 75% of the population was receiving food from relief workers, and over 150,000 relied upon aid for half of their food.[24]

India

The cyclone brought widespread rain to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, with very heavy rain falling in places on November 8–9. Port Blair recorded 130 mm (5.1 in) of rain on November 8, and there were a number of floods on the islands. MV Mahajagmitra, a 5,500-ton freighter en route from Calcutta to Kuwait, was sunk by the storm on November 12 with the loss of all fifty people on board. The ship sent out a distress signal and reported experiencing hurricane-force winds before it sank.[9][25] There was also widespread rain in West Bengal and southern Assam. The rain caused damage to housing and crops in both Indian states, with the worst damage occurring in the southernmost districts.[9]

Death toll

Two medical relief surveys were carried out by the Pakistan-SEATO Cholera Research Laboratory: the first in November and the second in February and March. The purpose of the first survey was to establish the immediate medical needs in the affected regions, and the second, more detailed, survey was designed as the basis for long-term relief and recovery planning. In the second survey, approximately 1.4% of the area's population was studied.[26]

The first survey concluded that the surface water in most of the affected regions had a comparable salt content to that drawn from wells, except in Sudharam, where the water was almost undrinkable with a salt content of up to 0.5%. The mortality was estimated at 14.2%—equivalent to a death toll of 240,000.[27] Cyclone-related morbidity was generally restricted to minor injuries, but a phenomenon dubbed "cyclone syndrome" was observed. This consisted of severe abrasions on the limbs and chest caused by survivors clinging to trees to withstand the storm surge.[27] Initially, there were fears of an outbreak of cholera and typhoid fever in the weeks following the storm,[28] but the survey found no evidence of an epidemic of cholera, smallpox or any other disease in the region affected by the storm.[27]

The totals from the second survey were likely a considerable underestimate as several groups were not included. The 100,000 migrant workers who were collecting the rice harvest, families who were completely wiped out by the storm and those who had migrated out of the region in the three months were not included. Excluding these groups reduced the risk of hearsay and exaggeration.[26] The survey concluded that the overall death toll was, at minimum, 224,000. The worst effects were felt in Tazumuddin, where the mortality was 46.3%, corresponding to approximately 77,000 deaths in Thana alone. The mean mortality throughout the affected region was 16.5%.[29]

The results showed that the highest survival rate was for adult males aged 15–49, while more than half the deaths were children under age 10, who only formed a third of the pre-cyclone population. This suggests that the young, old, and sick were at the highest risk of perishing in the cyclone and its storm surge. In the months after the storm, the mortality of the middle-aged was lower in the cyclone area than in the control region, near Dhaka. This reflected the storm's toll on the less healthy individuals.[30]

Aftermath

Government response

There have been mistakes, there have been delays, but by and large I'm very satisfied that everything is being done and will be done.

Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan[31]

The day after the storm struck the coast, three Pakistani gunboats and a hospital ship carrying medical personnel and supplies left Chittagong for the islands of Hatia, Sandwip and Kutubdia.[21] Teams from the Pakistani Army reached many of the stricken areas in the two days following the landfall of the cyclone.[32] Yahya visited East Pakistan on the way back from a trip to China. In a press conference in Dhaka, Yahya accepted the government had made “slips” and “mistakes” in their relief effort for the cyclone victims of then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh,) but he insisted that “everything was done within the limits of the Government.” He then returned to Rawalpindi[33]. No West Pakistani political leaders visited the East. [34]

In the ten days following the cyclone, one military transport aircraft and three crop-dusting aircraft were assigned to relief work by the Pakistani central government.[35] The central government said it was unable to transfer military helicopters from West Pakistan as the Indian government did not grant clearance to cross the intervening Indian territory, a charge the Indian government denied.[28] By November 24, the central government had allocated a further US$116 million to finance relief operations in the disaster area.[36] President Khan arrived in Dhaka to take charge of the relief operations on November 24. The governor of East Pakistan, Vice Admiral S. M. Ahsan, denied charges that the armed forces had not acted quickly enough and said supplies were reaching all parts of the disaster area except for some small pockets.[37]

A week after the cyclone's landfall, President Khan conceded that his government had made "slips" and "mistakes" in its handling of the relief efforts. He said there was a lack of understanding of the magnitude of the disaster. He also said that the 1970 general election slated for December 7 would take place on time, although eight or nine of the worst affected districts might experience delays, denying rumours that the election would be postponed.[31]

As the conflict between East and West Pakistan developed in March 1971, the Dhaka offices of the two government organisations directly involved in relief efforts were closed for at least two weeks, first by a general strike and then by a ban on government work in East Pakistan by the Awami League. Relief work continued in the field, but the long-term planning was curtailed.[38]

Criticism of government response

We have a large army, but it is left to the British Marines to bury our dead.

Political leaders in East Pakistan were deeply critical of the central government's initial response to the disaster. A statement released by eleven East Pakistan politicians ten days after the storm charged the government with 'gross neglect, callous indifference and utter indifference'. They also accused President Khan of playing down the news coverage.[36] On November 19, students held a march in Dhaka in protest of the speed of the government response,[40] and Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani addressed a rally of 50,000 people on November 24, when he accused the president of inefficiency and demanded his resignation. President Khan's political opponents in West Pakistan accused him of bungling the efforts and some demanded his resignation.[37] Awami League leader Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman described the destruction caused by the cyclone akin to a "Holocaust" and condemned the military junta's response as "criminal negligence".[41]

The Pakistan Red Crescent began to operate independently of the central government as the result of a dispute that arose after the Red Crescent took possession of twenty rafts donated by the British Red Cross.[42] A pesticide company had to wait two days before it received permission for two of its crop dusters, which were already in the country, to carry out supply drops in the affected regions. The central government only deployed a single helicopter to relief operations, with President Khan later stating that there was no point deploying any helicopters from West Pakistan as they were unable to carry supplies.[14]

A reporter for the Pakistan Observer spent a week in the worst hit areas in early January 1971 and saw none of the tents supplied by relief agencies being used to house survivors and commented that the grants for building new houses were insufficient. The Observer regularly carried front-page stories with headlines like, "No Relief Coordination", while publishing government statements saying, "Relief operations are going smoothly." In January, the coldest period of the year in East Pakistan, the National Relief and Rehabilitation Committee, headed by the editor of Ittefaq, said thousands of survivors from the storm were "passing their days under [the] open sky". A spokesman said families who were made homeless by the cyclone were receiving up to 250 rupees (US$55 dollars in 1971; equivalent to $341 in 2018) to rebuild, but that resources were scarce and he feared the survivors would "eat the cash".[43]

Political consequences

.svg.png.webp)

The Awami League, headed by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, swept to a landslide victory in the 1970 Pakistani general election, in part because of dissatisfaction over failure of the relief efforts by the central government. The elections for nine national assembly and eighteen provincial assembly seats had to be postponed until January 18 as a result of the storm.[44]

The central government's handling of the relief efforts helped exacerbate the bitterness felt in East Pakistan, swelling the resistance movement there. Funds only slowly got through, and transport was slow in bringing supplies to the devastated regions. As tensions increased in March 1971, foreign personnel evacuated because of fears of violence.[38] The situation deteriorated further and evolved into civil war and genocide. The conflict widened into the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 in December and concluded with the founding of Bangladesh. This would be one of the first times that a natural event helped to trigger a civil war.[45]

International response

India became one of the first nations to offer aid to Pakistan, despite the generally poor relations between the two countries, and by the end of November had pledged US$1.3 million (US$8.7 million in 2020 dollars) of assistance for the relief efforts.[46] The Pakistani central government refused to allow the Indians to send supplies into East Pakistan by air, forcing them to be transported slowly by road instead.[47] The Indian government also said that the Pakistanis refused an offer of military aircraft, helicopters and boats from West Bengal to assist in the relief operation.[48]

U.S. President Richard Nixon allocated a $10 million ($70 million in 2021) grant to provide food and other essential relief to the survivors of the storm, and the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan pledged that he would "assist the East Pakistan government in every way feasible."[49] The U.S. sent a number of blankets, tents and other supplies to East Pakistan. Six helicopters – two helicopters at an aid mission in Nepal and four from the U.S. – were also sent.[50] Some 200,000 tons of wheat were shipped from the U.S. to the stricken region.[43] By the end of November, there were 38 helicopters operating in the disaster area, ten of which were British and ten American. The Americans had provided about fifty small boats and the British seventy for supply distribution.[46]

CARE halted aid shipments to East Pakistan the week after the cyclone hit because of unwillingness to let the Pakistani central government handle distribution.[42] However, by January 1971, they had reached an agreement to construct 24,000 cement brick houses at a cost of about $1.2 million ($8 million in 2021).[43] American concerns about delays by the central government in determining how the relief should be used meant that US$7.5 million ($52 million in 2021) of relief granted by the United States Congress had not been handed over in March. Much of the money was earmarked to be spent on constructing cyclone shelters and rebuilding housing.[38] The American Peace Corps offered to send volunteers but were rebuffed by the central government.[46]

A Royal Navy task force, centred on HMS Intrepid and HMS Triumph, left Singapore for the Bay of Bengal to assist with the relief efforts. They carried eight helicopters and eight landing craft, as well as rescue teams and supplies.[49] Fifty soldiers and two helicopters were flown in ahead of the ships to survey the disaster area and bring relief work.[51] The task force arrived off the East Pakistan coast on November 24, and the 650 troops aboard the ships immediately began using landing craft to deliver supplies to offshore islands.[37] An appeal by the British Disasters Emergency Committee raised about £1.5 million (£25 million in 2021) for disaster relief in East Pakistan.[46][52]

The Canadian government pledged C$2 million of assistance. France and West Germany both sent helicopters and various supplies worth US$1.3 million.[46][51] Pope Paul VI announced that he would visit Dhaka during a visit to the Far East and urged people to pray for the victims of the disaster.[53] The Vatican later contributed US$100,000 to the relief efforts.[46] By the start of 1971, four Soviet helicopters were still operating in the region transporting essential supplies to hard-hit areas. The Soviet aircraft, which had drawn criticism from Bengalis, replaced the British and American helicopters that had operated immediately after the cyclone.[43]

The government of Singapore sent a military medical mission to East Pakistan which arrived at Chittagong on December 1, 1971. They were then deployed to Sandwip where they treated nearly 27,000 people and carried out a smallpox vaccination effort. The mission returned to Singapore on December 22, after bringing about $50,000 worth of medical supplies and fifteen tons of food for the victims of the storm.[54] The Japanese cabinet approved a total of US$1.65 million of relief funds in December. The Japanese government had previously drawn criticism for only donating a small amount to relief work.[55] The first shipment of Chinese supplies was a planeload of 500,000 doses of cholera vaccine, which was not necessary as the country had adequate stocks.[47] The Chinese government sent US$1.2 million in cash to Pakistan.[46] Mohammad Reza Pahlavi declared that the disaster was also an Iranian one and responded by sending two planeloads of supplies within a few days of the cyclone striking.[40] Many smaller, poorer Asian nations sent nominal amounts of aid.[46]

The United Nations donated US$2.1 million in food and cash, while UNICEF began a drive to raise a further million.[46] UNICEF helped to re-establish water supplies in the wake of the storm, repairing over 11,000 wells in the months following the storm.[56] UN Secretary-General U Thant made appeals for aid for the victims of the cyclone and the civil war in August, in two separate relief programs. He said only about $4 million had been contributed towards immediate needs, well short of the target of US$29.2 million.[57] By the end of November, the League of Red Cross Societies had collected US$3.5 million to supply aid to the victims of the disaster.[46]

The World Bank estimated that it would cost US$185 million to reconstruct the area devastated by the storm. The bank drew up a comprehensive recovery plan for the Pakistani government. The plan included restoring housing, water supplies and infrastructure to their pre-storm state. It was designed to combine with a much larger ongoing flood-control and development program.[58] The Bank provided US$25 million of credit to help rebuild the East Pakistan economy and to construct protective shelters in the region. This was the first time that the IDA had provided credit for reconstruction.[59] By the start of December, nearly US$40 million had been raised for the relief efforts by the governments of 41 countries, organizations and private groups.[58]

The Concert for Bangladesh

In 1971, ex-Beatle George Harrison and Bengali musician Ravi Shankar were inspired to organize The Concert for Bangladesh, in part from the Bhola cyclone, and from the civil war and genocide.[60] Although it was the first benefit concert of its type, it was extremely successful in raising money, aid and awareness for the region's plight.

Post-disaster

In December, the League of Red Cross Societies drafted a plan for immediate use should a comparable event to the cyclone hit other "disaster prone countries". A Red Cross official stated some of the relief workers sent to East Pakistan were poorly trained, and the organisation would compile a list of specialists. The UN General Assembly adopted a proposal to improve its ability to provide aid to disaster-stricken countries.

In 1966, the Red Crescent had begun to support the development of a cyclone warning system, which developed into a Cyclone Preparedness Programme in 1972, today run by the government of Bangladesh and the Bangladesh Red Crescent Society. The programme's objectives are to raise public awareness of the risks of cyclones and to provide training to emergency personnel in the coastal regions of Bangladesh.[61]

In the thirty years after the 1970 cyclone, over 200 cyclone shelters were constructed in the coastal regions of Bangladesh. When the next destructive cyclone approached the country in 1991, volunteers from the Cyclone Preparedness Programme warned people of the cyclone two to three days before it struck land. Over 350,000 people fled their homes to shelters and other brick structures, while others sought high ground. While the 1991 cyclone killed over 138,000 people, this was significantly less than the 1970 storm, partly because of the warnings sent out by the Cyclone Preparedness Programme. However, the 1991 storm was significantly more destructive, causing US$1.5 billion in damage (US$2 billion inflation-adjusted) compared to the 1970 storm's US$86.4 million in damage.[62][63]

Footage of the incident appeared in the film Days of Fury (1979), directed by Fred Warshofsky and hosted by Vincent Price.[64]

See also

- List of tropical cyclones

- List of Bangladesh tropical cyclones

- 1999 Odisha cyclone

- 1991 Bangladesh cyclone

- Cyclone Sidr (2007) – The next deadliest cyclone affecting Bangladesh in November with wind speed up to 260 km/h that killed at highest estimate 15,000 people in 2007.[65][66]

- 1973 Flores cyclone – The deadliest tropical cyclone recorded in the Southern Hemisphere

- Great Hurricane of 1780 – The deadliest hurricane in the Atlantic basin

- 1959 Mexico hurricane – The deadliest Pacific hurricane

- Typhoon Nina (1975) – The deadliest Pacific typhoon and the third deadliest tropical cyclone overall

References

- Longshore, David (2007). Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Cyclones (2 ed.). Facts On File Inc. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-8160-6295-9.

- "World: Highest Mortality, Tropical Cyclone". World Meteorological Organization's World Weather & Climate Extremes Archive. Arizona State University. November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- "The 16 deadliest storms of the last century". Business Insider India. September 13, 2017. Archived from the original on January 7, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- Julian Francis (November 9, 2019). "Remembering the great Bhola cyclone". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- Paula Ouderm (December 6, 2007). "NOAA Researcher's Warning Helps Save Lives in Bangladesh". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- "Cyclone". en.banglapedia.org. Banglapedia. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (1969). "Western North Pacific Tropical Storms 1969" (PDF). Annual Typhoon Report 1969. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- Frank, Neil; Husain, S. A. (June 1971). "The deadliest tropical cyclone in history?". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. American Meteorological Society. 52 (6): 438. Bibcode:1971BAMS...52..438F. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1971)052<0438:TDTCIH>2.0.CO;2.

- India Meteorological Department (1970). "Annual Summary — Storms & Depressions" (PDF). India Weather Review 1970. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Schwerdt, Richard (January 1971). "Worst Cyclone of the Century Batters East Pakistan". Mariners Weather Log. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 15 (1): 19.

- "Many Pakistan flood victims died needlessly". Lowell Sun. January 31, 1971. p. E3. Retrieved April 15, 2007 – via Newspapers.com.

- Sullivan, Walter (November 22, 1970). "Cyclone May Be Worst Catastrophe Of The Century". The New York Times.

- "East Pakistan Failed To Use Storm-Warning System". The New York Times. December 1, 1970.

- Zeitlin, Arnold (December 11, 1970). "The Day The Cyclone Came To East Pakistan". Stars and Stripes (European ed.). Darmstadt, Hesse. Associated Press. pp. 14–15. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Dunn, Gordon (November 28, 1961). "The tropical cyclone problem in East Pakistan" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- López-Carresi, Alejandro; Fordham, Maureen; Wisner, Ben; Kelman, Ilan; Gaillard, Jc (November 12, 2013). Disaster Management: International Lessons in Risk Reduction, Response and Recovery. Routledge. p. 250. ISBN 9781136179778.

- Climatological Center, Meteorological Development Bureau, Thai Meteorological Department, Thai Meteorological Department (2011). Tropical cyclones in Thailand: Historical data 1951–2010 (PDF) (Report). Thai Meteorological Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - https://www.academia.edu/14280191/CYCLONE_HAZARD_IN_BANGLADESH

- Kabir, M. M.; Saha, B. C.; Hye, J. M. A. "Cyclonic Storm Surge Modelling for Design of Coastal Polder" (PDF). Institute of Water Modelling. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- "Pakistan Death Toll 55,000; May Rise to 300,000". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 16, 1970.

- "Thousands of Pakistanis Are Killed by Tidal Wave". The New York Times. November 14, 1970.

- "Country Profile". EM-DAT: The International Disaster Database. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Sommer, Alfred; Mosley, Wiley (May 13, 1972). "East Bengal cyclone of November, 1970: Epidemiological approach to disaster assessment" (PDF). The Lancet. 1 (7759): 1029–1036. PMID 4112181. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Sommer, Alfred; Mosley, Wiley (May 13, 1972). "East Bengal cyclone of November, 1970: Epidemiological approach to disaster assessment" (PDF). The Lancet. 1 (7759): 1029–1036. PMID 4112181. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- "Cyclone Toll Still Rising". Florence Morning News. Associated Press. November 15, 1970. p. 1. Retrieved April 15, 2007 – via Newspapers.com.

- Sommer, Alfred; Mosley, Wiley (May 13, 1972). "East Bengal cyclone of November, 1970: Epidemiological approach to disaster assessment" (PDF). The Lancet. 1 (7759): 1029–1036. PMID 4112181. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Sommer, Alfred; Mosley, Wiley (May 13, 1972). "East Bengal cyclone of November, 1970: Epidemiological approach to disaster assessment" (PDF). The Lancet. 1 (7759): 1029–1036. PMID 4112181. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Schanberg, Sydney (November 22, 1970). "Pakistanis Fear Cholera's Spread". The New York Times.

- Sommer, Alfred; Mosley, Wiley (May 13, 1972). "East Bengal cyclone of November, 1970: Epidemiological approach to disaster assessment" (PDF). The Lancet. 1 (7759): 1029–1036. PMID 4112181. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Sommer, Alfred; Mosley, Wiley (May 13, 1972). "East Bengal cyclone of November, 1970: Epidemiological approach to disaster assessment" (PDF). The Lancet. 1 (7759): 7–8. PMID 4112181. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Schanberg, Sydney (November 22, 1970). "Yahya Condedes 'Slips' In Relief". The New York Times.

- "Toll In Pakistan Is Put At 16,000, Expected To Rise". The New York Times. November 15, 1970.

- Times, Sydney H. Schanberg; Special to The New York (November 28, 1970). "YAHYA CONCEDES 'SLIPS' IN RELIEF". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- Raghavan, Srinath (2013). 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-674-72864-6.

- Schanberg, Sydney (November 22, 1970). "Foreign Relief Spurred". The New York Times.

- "East Pakistani Leaders Assail Yahya on Cyclone Relief". The New York Times. Reuters. November 23, 1970.

- "Yahya Directing Disaster Relief". The New York Times. United Press International. November 24, 1970. p. 9.

- Durdin, Tillman (March 11, 1971). "Pakistanis Crisis Virtually Halts Rehabilitation Work in Cyclone Region". The New York Times. p. 2.

- Heitzman, James; Worden, Robert, eds. (1989). "Emerging Discontent, 1966–70". Bangladesh: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 29. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- "Copter Shortage Balks Cyclone Aid". The New York Times. November 18, 1970.

- Raghavan, Srinath (2013). 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-674-72864-6.

- "Pakistan relief program flounder as toll mounts". The Daily Tribune. Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin. Associated Press. November 23, 1970. p. 3. Retrieved August 5, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Zeitlin, Arnold (January 13, 1971). "Pakistan Cyclone Relief Still Jumbled and Inadequate". Long Beach Press-Telegram. Associated Press. p. P-11. Retrieved April 15, 2007 – via Newspapers.com.

- Jin Technologies (June 1, 2003). "General Elections 1970". Story of Pakistan. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Olson, Richard (February 21, 2005). "A Critical Juncture Analysis, 1964–2003" (PDF). USAID. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Halloran, Richard (November 29, 1970). "Pakistan Storm Relief a Vast Problem". The New York Times.

- Schanberg, Sydney (November 29, 1970). "People Still Dying Because Of Inadequate Relief Job". The New York Times.

- Schanberg, Sydney (November 25, 1970). "Pakistan Leader Visits Survivors". The New York Times.

- Zeitlin, Arnold (November 20, 1970). "Official Death Toll 148,116". The Daily Republic. Mitchell, South Dakota. Associated Press. p. 1. Retrieved April 15, 2007 – via Newspapers.com.

- Naughton, James (November 17, 1970). "Nixon Pledges $10-Million Aid For Storm Victims in Pakistan". The New York Times.

- "U.S. and British Helicopters Arrive to Aid Cyclone Area". The New York Times. Reuters. November 20, 1970.

- "DEC Appeals and Evaluations". Disasters Emergency Committee. Archived from the original on April 7, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- "Pope to Visit Pakistan". The New York Times. November 22, 1970.

- Choy Choi Kee (November 7, 1999). "Medical Mission to East Pakistan". Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- "Tokyo Increases Aid". The New York Times. December 2, 1970.

- UNICEF. "Sixty Years For Children" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 13, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- Brewer, Sam Pope (August 13, 1971). "Thant Again Asks Aid To Pakistanis". The New York Times.

- "World Bank Offers Plan to Reconstruct East Pakistan". The New York Times. December 2, 1970.

- "Cyclone Protection and Coastal Area Rehabilitation Project". World Bank. 2005. Archived from the original on March 4, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- "The Beatles Bible – Live: The Concert For Bangla Desh". August 1971. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- "Cyclone Preparedness Programme (CPP) Bangladesh Red Crescent Society" (PDF). iawe.org.

- "WHO | Reduced death rates from cyclones in Bangladesh: what more needs to be done?". www.who.int. Archived from the original on November 21, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- "Cyclone shelters save lives, but more needed". IRIN. January 30, 2008. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- "Watch Days of Fury (1979) on the Internet Archive". 1979.

- "BBC Weather Centre - World Weather - News - 15/11/2007 - Severe Cyclone Sidr hurtles towards Bangladesh". Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Bangladesh cyclone death toll hits 15,000". The Telegraph.

Further reading

- Scott Carney; Jason Miklian (2022). The Vortex: A True Story of History's Deadliest Storm, an Unspeakable War, and Liberation. Ecco. ISBN 978-0062985415.