1999 Bridge Creek–Moore tornado

On the evening of Monday, May 3, 1999, a large and exceptionally powerful F5 tornado registered the highest wind speeds ever measured globally; winds were recorded at 301 ± 20 miles per hour (484 ± 32 km/h) by a Doppler on Wheels (DOW) radar. Considered the strongest tornado ever recorded to have affected the metropolitan area, the tornado devastated southern portions of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, along with surrounding suburbs and towns to the south and southwest. The tornado covered 38 miles (61 km) during its 85-minute existence, destroying thousands of homes, killing 36 people (plus an additional five indirectly), and leaving US$1 billion (1999 USD) in damage,[5] ranking it as the fifth-costliest on record not accounting for inflation.[6] It was the first use of the tornado emergency statement by the National Weather Service.

| F5 tornado | |

|---|---|

The tornado near peak intensity | |

| Formed | May 3, 1999, 6:23 p.m. CDT (UTC−05:00) |

| Duration | 1 hour, 25 minutes |

| Dissipated | May 3, 1999, 7:48 pm. CDT (UTC−05:00) |

| Highest winds |

|

| Max. rating1 | F5 tornado |

| Fatalities | 36 fatalities (+5 indirect), 583 injuries[5] |

| Damage | $1 billion (1999 USD) $1.6 billion (2022 USD) |

| Areas affected | Grady, McClain, Cleveland and Oklahoma counties in Oklahoma; with the worst impacts occurring in the towns/cities of Bridge Creek, Moore, Oklahoma City, Del City, and Midwest City |

Part of the 1999 Oklahoma tornado outbreak 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale | |

The tornado first touched down at 6:23 p.m. Central Daylight Time (CDT) in Grady County, roughly two miles (3.2 km) south-southwest of the town of Amber. It quickly intensified into a violent F4, and gradually reached F5 status after traveling 6.5 miles (10.5 km), at which time it struck the town of Bridge Creek. It fluctuated in strength, ranging from F2 to F5 status before it crossed into Cleveland County where it reached F5 intensity for a third time shortly before entering the city of Moore. By 7:30 pm, the tornado crossed into Oklahoma County and battered southeastern Oklahoma City, Del City, and Midwest City before dissipating around 7:48 p.m. just outside Midwest City. A total of 8,132 homes, 1,041 apartments, 260 businesses, eleven public buildings, and seven churches were damaged or destroyed.

Large-scale search and rescue operations immediately took place in the affected areas. A major disaster declaration was signed by President Bill Clinton the following day (May 4) allowing the state to receive federal aid. In the following months, disaster aid amounted to $67.8 million. Reconstruction projects in subsequent years led to a safer, tornado-ready community. However, on May 20, 2013, nearby areas adjacent to the 1999 storm's track along with some of the same areas in the path of the tornado were again devastated by another large and violent EF5 tornado, resulting in 24 fatalities and extreme damage in the South Oklahoma City/Moore area.

Meteorological synopsis

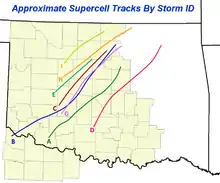

The Bridge Creek–Moore tornado was part of a much larger outbreak which produced 71 tornadoes across five states throughout the Central Plains on May 3 alone, along with an additional 25 that touched down a day later in some of the areas affected by the previous day's activity (some of which were spawned by supercells that developed on the evening of May 3), stretching eastward to the Mississippi River Valley. The most prolific tornadic activity associated with the May 3 outbreak – and the multi-day outbreak as a whole – occurred in Oklahoma; 14 of the 66 tornadoes that occurred within the state that afternoon and evening produced damage consistent with the Fujita scale's "strong" (F2–F3) and "violent" (F4–F5) categories, which, in addition to the areas struck by the Bridge Creek–Moore tornado family, affected towns such as Mulhall, Cimarron City, Dover, Choctaw and Stroud.[7]

On the morning of May 3, in its Day 1 Convective Outlook for the United States, the Storm Prediction Center (SPC) – based in Norman, approximately 10 miles (16 km) south of the tornado's eventual damage path – issued a slight risk of severe thunderstorms from southern Nebraska to central Texas. SPC analysis had detected the presence of a dry line that stretched from western Kansas into western Texas that was approaching a warm, humid air-mass over the Central Plains; the condition ahead of the dry line and a connecting trough positioned over northeastern Colorado appeared to favor the development of thunderstorms later that day that would contain large hail, damaging straight-line winds, and isolated tornadoes.[8][9]

SPC forecasters initially underestimated the atmospheric conditions that would support tornadic development that afternoon and evening. Around 4:00 a.m. CDT that morning, Doppler radar and wind profile data indicated a 90-knot (100 mph; 170 km/h) streak of elevated jet stream winds along the California−Nevada border, though weather balloon soundings sent up the previous evening by National Weather Service (NWS) offices in the western U.S. and numerical computer model data failed to detect the fast-moving air current as it moved ashore from the Pacific Ocean. In addition, the dry line was diffused, with surface winds behind and ahead of the boundary moving into the region from a southerly direction. SPC meteorologists began to recalculate model data during the morning to account for the stronger wind profiles caused by the jet streak; the data acknowledged that thunderstorms would occur within the Central Plains, but disagreed on the exact area of greatest severe weather risk.[9]

By 7:00 a.m. CDT, CAPE (convective available potential energy) values began exceeding 4,000 J/kg, an extreme value well above the climatological threshold favoring the development of severe thunderstorms.[10] Despite conflicting model data on the specified area where thunderstorms would develop, the newly available information that denoted a more favorable severe thunderstorm setup in that part of the state prompted the SPC to upgrade the forecasted threat of severe weather to a moderate risk for south-central Kansas, much of the western two-thirds of Oklahoma, and the northwestern and north-central portions of Texas at 11:15 a.m. CDT that morning, which now indicated that the atmospheric conditions present would "provide sufficient shear for a few strong or violent tornadic supercells given the abundant low level moisture and the high instability." The increasing threat of a severe weather/tornado outbreak for late that afternoon into the evening was reemphasized by NWS Norman forecasters in a Thunderstorm Outlook issued by the office at 12:30 p.m. CDT.[9][11]

By the early afternoon hours, forecasters at both the SPC and NWS Norman (both of which shared an office complex near Max Westheimer Airport at the time), realized that a major event was likely to take place based solely on observational data from radar and weather satellite imagery and balloon soundings, as the computer models remained uncooperative in helping meteorologists determine where the greatest threat of severe storms would occur.[9][12]

Conditions became highly conducive for tornadic development by 1:00 p.m. CDT as wind shear intensified over the region (as confirmed by an unscheduled balloon sounding flight conducted by the NWS Norman office), creating a highly unstable atmosphere. The sounding balloon recorded winds blowing southwesterly at 20 mph (32 km/h) and 50 mph (80 km/h) respectively at the surface and at the 12,000-foot (3,700 m) level, southerly winds of 40 mph (64 km/h) and westerly winds of 20 mph (32 km/h) at 20,000 feet (6,100 m); it also indicated that a capping inversion over the region was weakening in southwestern Oklahoma and north Texas. With the warm air above the surface cooling down, this allowed warm air at the surface the chance to rise and potentially create thunderstorms.[9][10] Although cirrus clouds − a bank of which had developed in west Texas and overspread portions of Oklahoma later in the morning − were present through much of the day, an area of clearing skies over western north Texas and southwestern Oklahoma early that afternoon allowed for the sun to heat up the moisture-laden region, creating significant atmospheric instability.[8]

At 3:49 p.m. CDT, the SPC − having gathered enough data to surmise that there was a credible threat of a significant severe weather outbreak occurring within the next few hours − amended its Day 1 Convective Outlook to place the western nine-tenths of the main body of Oklahoma, central and south-central Kansas and the northern two-thirds of Texas under a high severe weather risk, denoting a higher than normal probability of strong (F2+) tornadoes within the risk area.[13] About 40 minutes after the revised outlook's issuance, at 4:30 p.m. CDT, the SPC issued a tornado watch for western and central Oklahoma, effective from 4:45 p.m. until 10:00 p.m. CDT that evening, for the threat of tornadoes, hail up to three inches (7.6 cm) in diameter, wind gusts to 80 mph (130 km/h) and intense lightning. As that happened, the first thunderstorm cell of the unfolding event had already formed over southwestern Oklahoma.[10][14]

Storm development and track

The thunderstorm that eventually produced the F5 tornado began developing around 3:20 p.m. CDT that afternoon over northeastern Tillman County (southwest of Faxon). Despite the lack of overall lift prevalent in the region, the storm formed out of a contrail-like horizontal area of convective clouds that developed during peak surface heating over southwestern Oklahoma, located well ahead of the dry line that was still positioned farther to the west, which provided enhanced lift and speed shear necessary to develop the supercell.[15] Tracking northeast, the storm strengthened and entered Comanche County shortly after 4:00 p.m. CDT.[16] By 4:15 p.m. CDT, the NWS Norman office issued a severe thunderstorm warning for Comanche County, as the initial storm continued to rapidly intensify over the southern half of the county; there, hail up to 1.75 inches (4.4 cm) in diameter fell.[7][17]

As the supercell's mesocyclonic rotation began to rapidly strengthen at the cloud base, a tornado warning was issued for the counties of Comanche, Caddo, and Grady at 4:50 p.m. CDT;[18] one minute later, a small tornado roughly 25 yards (75 ft) in diameter − the first of fourteen associated with supercell "A" (NWS Norman designated lettered names for the three tornado-producing supercells in the outbreak in storm surveys) − touched down seven miles (11 km) east-northeast of Medicine Park along U.S. Route 62. Five more tornadoes developed as the storm continued northeast; a sixth one, which would be given an F3 rating, touched down a short time later and caused substantial damage in central Grady County, including some to the Chickasha Municipal Airport, where roofs were torn off of two hangars.[16]

At 6:23 p.m. CDT, a ninth tornado associated with supercell "A" touched down about two miles (3.2 km) south-southwest of Amber.[16] The tornado quickly intensified in both strength and size as it crossed Oklahoma State Highway 92, attaining F4 strength about 4 miles (6.4 km) east-northeast of Amber. It quickly became a wedge tornado, varying between one-quarter and one mile (0.40 and 1.61 km) in width at various points throughout the track. Damage consistent with this rating was sustained over the following 6.5 miles (10.5 km) of the path before striking Bridge Creek. There, it attained the highest-possible rating on the Fujita Scale, F5. A mobile Doppler weather radar recorded winds of 301 mph (484 km/h) within the tornado at Bridge Creek, the highest wind speed ever recorded on Earth.[19] Since the record for maximum winds are reported from only non-tornadic events, however, the 253 mph (407 km/h) wind gust from Cyclone Olivia in 1996 retained the title.[20][21]

Damage in Bridge Creek was extreme, as many homes were swept away completely, leaving only concrete slabs where the structures once stood. Damage surveyors noted that the remaining structural debris from some of the homes in this area was finely granulated into small fragments, and that trees and shrubs were completely debarked.[22] A few of these homes were bolted to their foundations. Approximately 200 houses and mobile homes were destroyed, and hundreds of other structures were damaged. The Ridgecrest Baptist Church in Bridge Creek was also destroyed in the process. Extensive ground scouring occurred, and vehicles were thrown hundreds of yards from where they originated, including a mangled pickup truck that was found wrapped around a telephone pole. About one inch (25 mm) of asphalt was scoured off one road.

About twelve people died in Bridge Creek, nine of whom were in mobile homes; all fatalities and the majority of injuries were concentrated in the Willow Lake and Southern Hills Additions and Bridge Creek Estates, consisting mostly of mobile homes. Over 39 people were injured in the area as well.[21][23] Continuing northeastward, the tornado briefly weakened to F4 status before re-strengthening to F5 intensity as it neared the Grady-McClain County line, where a car was thrown roughly 0.25 mi (0.40 km) in the air, and a well-built home with anchor bolts was reduced to a bare slab.[21] At this time, it had attained a width of one mile (1.6 km), having grown to its largest width after crossing the South Canadian River into the southern Oklahoma City limits. The tornado then became quickly rain-wrapped; Jim Gardner, then-helicopter pilot for KFOR-TV, reported during the station's live coverage of the storm that the tornado was at least one mile wide, and was embedded (or "rain-wrapped") in the precipitation core associated with the main circulation, making it difficult to see.[16]

As it was becoming clear that a particularly violent tornado was moving into some of the most densely populated areas of central Oklahoma, around 6:57 p.m. CDT, NWS Norman issued the first-ever tornado emergency for southern portions of the Oklahoma City metropolitan area. David Andra, a meteorologist at the NWS Norman office, said that, in drafting the enhanced warning, he wanted to "paint the picture [to residents in the areas that were to be affected by the storm] that a rare and deadly tornado was imminent in the metro area." For its initial usage, the enhanced wording was released as part of a standalone Severe Weather Statement (NWS code: SVS), which were (and still are) normally meant to update the public on an existing tornado warning or severe thunderstorm warning. For tornado warnings, the SVS provides updated information on the approximate location of the storm's base-level rotation or, if it occurred after the initial warning was issued, a tornado reported by the public, civil defense personnel or storm spotters, or with the later advent of dual-polarization radar in the early 2010s, verified by radar-detected debris signatures. (In future issuances, tornado emergencies were issued within either the initial tornado warning issuance or an SVS providing updated information on a tornado warning already in effect.)[24][25] Two minutes later, at 6:59 p.m. CDT, the SPC issued a Particularly Dangerous Situation tornado watch for much of the central third of Oklahoma, effective from 7:15 p.m. until midnight CDT on the early morning of May 4; the SPC watch product discussion noted that the extreme instability compensated for "somewhat marginal" wind shear to enhance the threat of strong to violent tornadoes.[14]

Paralleling Interstate 44, the tornado moved into McClain County, where it crossed the highway twice at F4 intensity, killing a woman who was blown out from an underpass where she was attempting to seek shelter after being dragged down the embankment by the intense channeling winds; her 11-year-old son − with whom the woman vacated their stalled car nearby − survived, staying held tight onto the steel girders of the overpass. A man who helped the mother and son up the overpass suffered severe injuries to his leg, which was partially sliced by a highway sign thrown by the winds.[21][26] At 7:10 p.m. CDT, a satellite tornado touched down over an open field north of Newcastle; it was rated as an F0 due to lack of damage. In McClain County, 38 homes and two businesses were destroyed and 40 homes, some of which were leveled at F4 intensity, were flattened; seventeen people were injured.[21]

After crossing the Canadian River, the tornado entered Cleveland County and weakened to F2 intensity. By this time, it had entered the south side of Oklahoma City. Several minutes after entering the county, it re-attained F4 status, and then moved directly into the city of Moore, reaching F5 intensity for a third time. Some of the most severe damage took place in Cleveland County, mainly in Moore, where eleven people were killed and 293 others were injured. The tornado caused an estimated $450 million in damage across the county. The first area impacted in Moore was the Country Place Estates subdivision, where 50 homes were destroyed and one was swept cleanly from its foundation at F5 intensity. Several vehicles were picked up and tossed nearly 0.25 mi (0.40 km) away from their previous location. According to local police, an airplane wing, believed to have been from an airport in Grady County (possibly lofted into the storm's updraft when the supercell's sixth tornado hit Chickasha Municipal Airport), was found near Country Place Estates. Then, the powerful tornado struck the densely populated Greenbriar Eastlake Estates at F5 intensity, killing three people and reducing entire rows of homes to rubble. In one instance, four adjacent homes were completely destroyed, with only concrete slabs remaining, warranting an F5 rating at that location. Three other homes in this housing division also received F5 damage, with the remaining destruction rated high-end F4. Severe debarking of trees was noted in this area. At the Emerald Springs Apartments, three more people were killed and a two-story apartment building was mostly flattened.[7]

As the tornado entered Cleveland County, NWS Norman activated emergency procedures, preparing to evacuate staff and others present at the facility in the event that the supercell should turn right, placing areas surrounding the Norman campus in the tornado's path (under NOAA protocol in situations posing a danger to personnel at local Weather Forecast Offices and related guidance centers, responsibility over the issuance of warnings and statements on the unfolding outbreak would have been transferred to the nearest NWS Forecast Office, based in Tulsa, while the SPC's forecasting responsibilities would be turned over to the 557th Weather Wing at Offutt Air Force Base). The supercell, however, continued on a northeastward track, sparing the Norman area.[26]

Safety precautions were also enacted elsewhere in and near the storm's path; council members and citizens at Moore City Hall − where a council meeting was scheduled to be held that evening − sheltered in place in the building's first-floor restrooms, away from the multiple large-pane windows at its facade. In downtown Oklahoma City, spectators attending sporting events held that evening involving two of the city's minor league teams – a regular season Pacific Coast League baseball game between the Oklahoma RedHawks and the Memphis Redbirds (which was suspended during the second inning) and Game 2 of the Ray Miron President's Cup series between the Central Hockey League's Oklahoma City Blazers and Huntsville Channel Cats – were also evacuated to shelter in an underground storage area connected to the Southwestern Bell Bricktown Ballpark and Myriad Convention Center amid concerns that the storm would jog northward and place Oklahoma City itself in the tornado's path. Flights were grounded at Will Rogers World Airport as the northern edge of the supercell (containing hail up to 1.25 inches (3.2 cm), straight-line wind gusts up to 70 mph (110 km/h), and moderate to heavy rain) approached the area; the tornado turned right, away from southwestern parts of the city proper located within Oklahoma County, shortly before airport officials began evacuating employees and visitors at the terminals. Traffic on Interstate 35 in south Oklahoma City and north Moore became backed up for several miles, as drivers evacuated from their vehicles to seek shelter under an overpass overlooking South Shields Boulevard.[26]

Just outside the Eastlake Estates, an honors ceremony was being held at Westmoore High School at the time of the tornado. Adequate warning time allowed those at the school to seek shelter, however, and more than 400 adults and students attending the awards ceremony at the school's auditorium were moved to the main building, sheltering in reinforced hallways and bathrooms. Ultimately, Westmoore High sustained heavy damage and dozens of cars that were in the school's parking lot were tossed around, some of which were completely destroyed or thrown into nearby homes. No injuries took place at the school, though a horse was found dead between a couple of destroyed cars in this area. The tornado proceeded through additional densely populated areas of Moore shortly thereafter, where several large groups of homes were flattened in residential areas, with a mixture of high-end F4 and low-end F5 damage noted in the survey. Near Janeway Avenue, four people were killed in an area where multiple homes were completely destroyed. A woman, who took shelter with her husband and two children, was also killed when she was blown out from under the Shields overpass on Interstate 35. The tornado weakened somewhat as it moved through the Highland Park neighborhood of Moore, but still caused widespread F3 and F4 damage.[7][26][27]

The tornado entered Oklahoma County and struck the southeast fringes of Oklahoma City, where it re-intensified to high-end F4 strength; two people were killed in this area as a building housing a trucking company was completely destroyed. Shortly before it tracked into the county, patrons and employees at Crossroads Mall were evacuated to storage areas in the basement of the building.[26] Numerous industrial buildings were leveled in this area of the city. A freight railroad car, weighing 36,000 lb (16,000 kg) was thrown 0.75 mi (1.21 km). The car bounced as it traveled, remaining airborne for 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) at a time. Multiple homes were also completely destroyed in southeast Oklahoma City, and one woman was killed in that area. Crossing Southeast 44th Street into Del City, the tornado moved through the highly populated Del Aire housing addition, killing six people and damaging or destroying hundreds of homes, with many sustaining F3 to F4 damage.[7] Seven people were killed as a direct result of the tornado in Del City, and hundreds of homes were damaged or destroyed.[28]

The tornado then crossed Sooner Road, and subsequently damaged an entry gate and several buildings at Tinker Air Force Base; it then crossed 29th Street into Midwest City, destroying one building at the Boeing Complex and damaging two others. Widespread F3/F4 damage continued as the tornado moved across Interstate 40, affecting a large business district. Approximately 800 vehicles at Hudiburg Auto Group were damaged, located just south of Interstate 40. Hundreds of vehicles at the dealership were moved from their original location on the lot, and dozens of vehicles (including 30 awaiting tune-ups or repairs at Morris' Auto Machine and Supply, and an unoccupied Mid-Del School District bus) were picked up and tossed northward across the interstate into several motels, being carried a distance of approximately two-tenths of a mile. Numerous motels and other businesses, including Hampton Inn, Comfort Inn, Inn Suites, Clarion Inn, Cracker Barrel, and portions of Rose State College, were destroyed. While some of the damage through this area was rated high-end F4, low-end F5 was considered. The tornado then continued into another residential area located between Southeast 15th and Reno Avenue, where three fatalities occurred. Damage consistent with high-end F4 wind speeds was inflicted to four homes in this area. Two of these homes were located between Southeast 11th and 12th Streets, near Buena Vista, and the other two homes were located on Will Rogers Road, just south of Southeast 15th. Damage then diminished rapidly to F0/F1 strength as the tornado crossed Reno Avenue, before dissipating three blocks north of Reno, between Sooner Road and Air Depot Boulevard (south of the Midwest City–Oklahoma City line). Throughout Oklahoma County, twelve people were killed and 234 others were injured while losses amounted to $450 million.[7][26][27]

Impact and casualties

Thirty-six people were killed as a direct result of the storm and five more died of indirect causes in the hours following it; most of the indirect deaths were due to heart attacks or injuries suffered while trying to seek shelter. One survivor was uninjured but died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in an apparent reaction to losing his home in the tornado. According to the Oklahoma Department of Health, an estimated 583 people were injured by the tornado, accounting for those who did not go to the hospital or were unaccounted for.[16] A total of 8,132 homes, 1,041 apartments, 260 businesses, eleven public buildings, and seven churches were damaged or destroyed. Estimated damage costs totaled $1.2 billion, making it the first recorded tornado to exceed $1 billion in total estimated damages. The Bridge Creek−Moore tornado produced an estimated 220 cubic yards (170 m3) of debris from the buildings that were destroyed.[29][30]

This was the deadliest tornado recorded in Oklahoma since a long-track F5 tornado killed 107 people in Woodward on April 9, 1947. It was also the deadliest tornado ever recorded in the Oklahoma City metropolitan area; the previous record was held by an F4 tornado that affected southwestern portions of the city on June 12, 1942, which killed 31 people and caused $500,000 in damage ($12.1 million in (2022 USD) when adjusted for inflation).[31] It was the costliest tornado in U.S. history until it was surpassed by an EF4 tornado that hit Tuscaloosa and northern portions of Birmingham, Alabama, on April 27, 2011, causing an estimated $2.45 billion in damage (as of 2015, the Bridge Creek–Moore tornado is the fourth-costliest tornado, having also been surpassed by the EF5 tornadoes that hit Joplin on May 22, 2011, and areas of Moore near the 1999 storm track on May 20, 2013).[30] In addition, this was the 50th and final tornado in the United States to be rated F5 on the original Fujita-Scale before the current Enhanced Fujita-Scale was implemented on February 1, 2007.

NWS researchers estimated that the death toll from the storm would likely have exceeded 600 had it not been for the advanced warning through local television and radio stations and proper safety precautions being exercised by area residents. Because Oklahoma has historically been climatologically prone to tornadic activity, Oklahoma City-area television stations KFOR-TV (channel 4), KOCO-TV (channel 5) and KWTV (channel 9) – each of which provided continuous coverage of the outbreak that spawned the Bridge Creek–Moore tornado and its ensuing aftermath from the event's start on the afternoon of May 3 through the evening of May 4 – have long relied on state-of-the-art radar technology and visual confirmation from news helicopters and in-house storm chasing fleets to cover severe weather events. The three network-affiliated stations, other local media outlets and the NWS also routinely conduct various tornado preparedness symposiums to ensure residents undertake precautions in the event a tornado or other severe weather affects their area.[30]

Aftermath

Following the destructive and widespread tornado outbreak, President Bill Clinton signed a major disaster declaration for eleven Oklahoma counties (including the four that were affected by the Bridge Creek–Moore tornado, Cleveland, McClain, Grady and Oklahoma) on May 4. In a press statement by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), then-director James Lee Witt stated that, "The President is deeply concerned about the tragic loss of life and destruction caused by these devastating storms."[32] The American Red Cross opened ten shelters overnight across central Oklahoma, housing 1,600 people immediately following the disaster. By May 5, this number had lowered to 500. Throughout May 5, several post-disaster teams from FEMA were deployed to the region, including emergency response and preliminary damage assessment units. The U.S. Department of Defense deployed the 249th Engineering Battalion and placed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on standby for assistance. Medical and mortuary teams were also sent by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.[33] By May 6, donation centers and phone banks were being established to create funds for victims of the tornadoes.[34]

Continuing search and rescue efforts for thirteen people who were listed as missing through May 7 were assisted by urban search and rescue dogs from across the country.[35] Nearly 1,000 members of the Oklahoma National Guard were deployed throughout the affected region. The American Red Cross had set up ten mobile feeding stations by this time and stated that 30 more were en route.[36] On May 8, a disaster recovery center was opened in Moore for individuals recovering from the tornadoes.[37] According to the Army Corps of Engineers, roughly 500,000 cubic yards (382,277 cubic meters) of debris was left behind and would likely take weeks to clear.[38] Within the first few days of the disaster declaration, relief funds began being sent to families who requested aid. By May 9, roughly $180,000 had been approved by FEMA for disaster housing assistance.[39]

Debris removal finally began on May 12 as seven cleanup teams were sent to the region, more were expected to join over the following days.[40] That day, FEMA also declared that seven counties − Canadian, Craig, Grady, Lincoln, Logan, Noble and Oklahoma − were eligible for federal financial assistance.[41] By May 13, roughly $1.6 million in disaster funds had been approved for housing and businesses loans.[42] This quickly rose to more than $5.9 million over the following five days.[43] By May 21, more than 3,000 volunteers from across the country traveled to Oklahoma to help residents recover; 1,000 of these volunteers were sent to Bridge Creek to clean up debris, cut trees, sort donations and cook meals.[44] With a $452,199 grant from FEMA, a 60-day outreach program for victims suffering tornado-related stress was set up to help them cope with trauma.[45]

Applications for federal aid continued through June, with state approvals reaching $54 million on June 3. By this date, the Army Corps of Engineers reported that 964,170 cubic yards (737,160 cubic meters), roughly 58%, of the 1.65 million cubic yards (1.26 million cubic meters) of debris had been removed.[46] Assistance for farmers and ranchers who suffered severe losses from the tornadoes was also available by June 3.[47] After more than a month of being open, emergency shelters were set to be closed on June 18.[48] On June 21, an educational road show made by FEMA visited the hardest hit areas in Oklahoma to urge residents to build storm cellars.[49] According to FEMA, more than 9,500 residents applied for federal aid during the allocated period in the wake of the tornadoes. Most of the applicants lived in Oklahoma and Cleveland counties, 3,800 and 3,757 persons respectively. In all, disaster recovery aid for the tornadoes amounted to roughly $67.8 million by the end of July 2.[50]

Over the following four years, a $12 million project to construct storm shelters for residents across the Oklahoma City metropolitan area was enacted. The goal was to create a safer community in a tornado-prone region. By May 2003, a total of 6,016 safe rooms were constructed. On May 9, 2003, the new initiative was put to the test as a tornado outbreak in the region spawned an F4 tornado, which took a path similar to that of the Bridge Creek–Moore tornado. Due to the higher standards for public safety, no one was killed by the 2003 tornado, a substantial improvement in just four years.[51] On May 20, 2013, an EF5 tornado impacted some of the same areas affected by the 1999 storm, tracking through the heart of Moore. Throughout the city, 24 people were killed (along with one additional person who died as an indirect result of the tornado) and more than 230 were injured.[52][53]

Highway overpass misconception

From a meteorological and safety standpoint, the tornado also brought into question the use of highway overpasses as shelters. Prior to the events on May 3, 1999, videos of people taking shelter in overpasses during tornadoes in the past – most notably one filmed near Wichita, Kansas, during the April 26, 1991 tornado outbreak involving a television news crew from Wichita NBC affiliate KSNW (channel 3), who decided to shelter under an overpass on the Kansas Turnpike alongside other bystanders who found themselves in the path of the tornado – gave the public misunderstanding that overpasses provided shelter from tornadoes. For nearly twenty years, meteorologists had questioned the safety of these structures; however, they lacked incidents involving loss of life. In the aforementioned 1991 footage, the subjects were able to safely ride out the tornado due to an unlikely combination of events: the storm in question was a weak tornado, the tornado did not directly strike the overpass, and the overpass itself was of a unique design.[54]

Indeed, the May 1999 tornado outbreak proved concerns that highway overpasses were dangerous places to seek shelter during a tornado, as three overpasses were directly struck by tornadoes, with a fatality taking place at each one. Two of these were from the F5 Bridge Creek–Moore tornado while the third was from a comparatively less intense F2, which struck a rural area in Payne County, north-northeast of Oklahoma City; many other serious to life-threatening injuries also occurred at these locations.[55] The casualties at the three overpasses are attributed to the Venturi effect, as tornadic winds were accelerated in the confined space of each of the overpasses that the tornadoes passed through, increasing the chances that those riding out the tornado would be blown out at high speeds even if they tried to anchor themselves to the girders. According to a study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), seeking shelter in an overpass "is to become a stationary target for flying debris."[56]

Engineering flaws

Preliminary damage surveys conducted by a group of structural engineers from Texas Tech University determined that many of the frame homes that were destroyed by the Bridge Creek−Moore tornado were constructed below minimal residential building code standards, discovering some structural deficiencies that violated codes, which were considered to be inadequate for regions prone to tornadic activity (under federal building code standards, frame homes that were properly strapped and bolted would have withstood winds between 152 and 157 miles per hour (245 and 253 km/h), equivalent to an F2 tornado). The team, led by meteorological researcher Charles Doswell and storm damage engineer/meteorologist Tim Marshall, determined that nails attached to a plywood roof deck in one damaged home were not properly anchored to the rafters; several homes in rural areas that were swept nearly 300 feet (91 m) from their original location did not have anchor bolts that secured the frame to their foundations, as was the case at Country Place Estates, where the homes − which left a trail of debris strewn 3,000 feet (910 m) away from their location − were attached to the concrete foundations by tapered cut nails that extended only a half-inch to the bases; many homes that were left at least partially standing also had their garage doors (mainly those made from aluminum material) collapse inward, allowing the tornado's destructive winds to enter the houses.[30]

Marshall discovered other building and vehicle remains that became debris missiles, including a twisted 36-inch (0.91 m) steel beam, a steel leg broken off of a lawn chair that was impaled into a 5-by-5-inch (13 cm × 13 cm) post by the violent winds and a six-foot (180 cm) section of a sewer pipe that was blown into the interior hallway of one house through the front door. The team's findings also revealed that several homes were obliterated before they experienced the full impact of the vortex's peak wind velocities, with some disintegrating as the external winds surrounding the parent tornado reached speeds of F2 intensity. Three months later, as homes were being built in the damage path, Marshall found their construction to be scarcely superior to that of the homes destroyed in the May 3 storm.[30]

The FEMA corroborated with Doswell and Marshall's findings in its Building Performance Assessment Team Report on the May 3 outbreak, noting that much of the structural damage resulted from strong winds generated by the tornado and associated windborne debris that often "produced forces on buildings not designed to withstand such forces" and in some cases, were due to improper construction techniques and "poor selection" of materials used in their construction. The report acknowledged that federal construction code requirements needed to be revised above the then-current minimum standards to allow newer buildings to better withstand higher wind speeds consistent with tornadoes of lesser intensity than the one that devastated Bridge Creek and Moore, thereby lessening the degree of damage, fatalities and injuries that are probable in buildings of typically less reinforced construction.[57][58]

In popular culture

The events and survivor accounts of the tornado were profiled in an episode of Discovery Channel's Critical Rescue (produced by New Dominion Pictures), aired in 2003 and NHNZ's Ultimate Disaster (Mega Disaster) on National Geographic Channel in 2006.[59][60]

See also

- List of North American tornadoes and tornado outbreaks

- List of tornadoes with confirmed satellite tornadoes

- List of tornadoes in the 1999 Oklahoma tornado outbreak − a chronological list of the tornadoes (as compiled in National Weather Service damage surveys and local storm reports) that occurred over the seven-day period of the outbreak from May 2 to 8, 1999

- 2003 Moore–Choctaw tornado − a weaker tornado of peak F4 intensity that followed a similar path four years later

- 2013 Moore tornado − a similarly destructive, but less deadly EF5 tornado that affected nearby areas fourteen years later

- 2013 El Reno tornado – the widest tornado on record that impacted nearby areas fourteen years later

- List of Cleveland County, Oklahoma tornadoes

Notes

- It is officially accepted that the rating for this tornado is F5; however, the ±20 mph (32 km/h) wind speed ambiguity has occasionally led some people to suggest that this tornado may have briefly been an F6 tornado. On the original Fujita Scale, F6 was a theoretical classification for an "inconceivable tornado", with a wind speed in excess of 318 mph (512 km/h), but no tornado ever produced winds officially at or above 319 mph (513 km/h). The United States National Weather Service has officially maintained that the Bridge Creek–Moore tornado is an F5 tornado, and will not be reclassified F6.[2]

References

- "Doppler on Wheels". Center for Severe Weather Research. May 3, 1999. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- "Frequently Asked Questions About The May 3, 1999 Bridge Creek/OKC Area Tornado". National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office, Norman, Oklahoma. April 28, 2014. Archived from the original on January 27, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- "DOW Measurements in Tornadoes". Extreme Planet. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- Wurman, Joshua; Alexander, Curtis; Robinson, Paul; Richardson, Yvette (2007). "Low-Level Winds in Tornadoes and Potential Catastrophic Tornado Impacts in Urban Areas". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 88 (1): 31–46. Bibcode:2007BAMS...88...31W. doi:10.1175/BAMS-88-1-31.

- "The Great Plains Tornado Outbreak of May 3–4, 1999: Storm A Information". National Weather Service Forecast Office, Norman, Oklahoma. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 22, 2013. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- "The 10 Costliest U.S. Tornadoes since 1950". Storm Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena with Late Reports and Corrections" (PDF). Storm Data. National Climatic Data Center. 41 (5). May 1999. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 11, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- "Severe Weather Outlook at 6:30 a.m. CDT on May 3, 1999". Storm Prediction Center. May 3, 1999. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- Nancy Mathis (2007). "Searching for Clues". Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. pp. 61–64, 67–68. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- "Meteorological Summary of the Great Plains Tornado Outbreak of May 3–6, 1999". National Weather Service Forecast Office, Norman, Oklahoma. May 3, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "Severe Weather Outlook for 11:15 a.m. CDT". Storm Prediction Center. May 3, 1999. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- James Murnan (April 20, 2009). "Remembering May 3, 1999". National Weather Service Forecast Office, Norman, Oklahoma. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 12, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "Severe Weather Outlook for 3:49 p.m. CDT". Storm Prediction Center. May 3, 1999. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "SPC Watch Archive: Tornado Watches – May 3, 1999". Storm Prediction Center. May 3, 1999. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- Nancy Mathis (2007). "The Twister's Aftermath". Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- "The Great Plains Tornado Outbreak of May 3–4, 1999: Storm A Information". National Weather Service Forecast Office, Norman, Oklahoma. May 3, 2010. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "1999 OUN Severe Thunderstorm Warning #184". National Weather Service Norman, Oklahoma. May 3, 1999. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via Iowa Environmental Mesonet.

- "1999 OUN Tornado Warning #37". National Weather Service Norman, Oklahoma. May 3, 1999. Retrieved October 20, 2015 – via Iowa Environmental Mesonet.

- "Doppler on Wheels". Center for Severe Weather Research. 2010. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "Highest surface wind speed – Tropical Cyclone Olivia sets world record". World Records Academy. January 26, 2010. Archived from the original on October 17, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "Storm Events Database – Event Details". National Climatic Data Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 3, 1999.

- Jim LaDue; Tim Marshall; Kevin Scharfenberg (2012). "Discriminating EF4 and EF5 Tornado Damage" (PDF). National Weather Service Forecast Office, Norman, Oklahoma. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- "The Indefinitive List of the Strongest Tornadoes Ever Recorded (Part I) |". Extreme Planet. Archived from the original on September 3, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- "South Oklahoma Metro Tornado Emergency". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. May 3, 1999. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "May 3rd, 1999 from the NWS's Perspective". The Southern Plains Cyclone. National Weather Service. 2 (2). Spring 2004. Archived from the original on November 8, 2004. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- Nancy Mathis (2007). "Inside the Bear's Cage". Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. pp. 125–126, 133–142. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- Nancy Mathis (2007). "A Twister's Journey". Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. pp. 154–157. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- "Del City to dedicate tornado victim memorial". KWTV. Griffin Communications. May 6, 2008. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- "The 1999 Oklahoma Tornado Outbreak: 10-Year Retrospective" (PDF). Risk Management Solutions. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 1, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- Nancy Mathis (2007). "The Twister's Aftermath". Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. pp. 180–188. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- "Top Ten Deadliest Oklahoma Tornadoes (1875–present)". National Weather Service Forecast Office, Norman, Oklahoma. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- "President Declares Major Disaster for Oklahoma" (Press release). Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 4, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Oklahoma/Kansas Tornado Disaster Update" (Press release). Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 5, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Plains States Tornado Update" (Press release). Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 6, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "FEMA Sends Urban Search & Rescue Dogs to Oklahoma". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 7, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Plains States Tornado Disaster Update" (Press release). Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 7, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "FEMA and State Open Disaster Recovery Center in Moore". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 7, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Debris Removal Begins; Army Corps of Engineers Targets Public Access and Property". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 7, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "First Checks Approved for Oklahoma Storm Victims". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 9, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Debris Removal Underway in Oklahoma City, Mulhall, and Choctaw; Stroud Set for Thursday". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 12, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Seven Oklahoma Counties Get Expanded Disaster Assistance". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 12, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Oklahoma Tornado Disaster Update" (Press release). Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 13, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Oklahoma Disaster Recovery News Summary" (Press release). Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 18, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Flood of Volunteers Aids Tornado Victims". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 21, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Help Available To Those Coping With Tornado-Related Stress". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 21, 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Oklahoma Disaster Aid Tops $54 Million". Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 3, 1999. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- "Disaster Assistance is Available to Oklahoma Farmers and Ranchers". Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 3, 1999. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- "Disaster Recovery Centers To Close in Bridge Creek And Dover". Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 14, 1999. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- "Safe Room Show Visits Oklahoma". Federal Emergency Management Agency. June 21, 1999. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- "Almost 9,500 Oklahomans Register For Disaster Recovery Aid More Than $67.8 Million in Grants And Loans Approved". Federal Emergency Management Agency. July 7, 1999. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- "Residents Survive May 2003 Tornado". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 9, 2003. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- Chelsea J. Carter; Brian Todd; Michael Pearson (May 21, 2013). "Crews shift from rescue to recovery a day after Oklahoma tornado, official says". CNN. Moore, Oklahoma: Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- Malcolm Ritter (May 21, 2013). "Oklahoma twister tracked path of 1999 tornado". MSN.com. MSN. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- Daniel J. Miller; Charles A. Doswell III; Harold E. Brooks; Gregory J. Stumpf; Erik Rasmussen (1999). "Highway Overpasses as Tornado Shelters". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 13, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- Daniel J. Miller; Charles A. Doswell III; Harold E. Brooks; Gregory J. Stumpf; Erik Rasmussen (1999). "Highway Overpasses as Tornado Shelters: Events on May 3, 1999". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. p. 5. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- Daniel J. Miller; Charles A. Doswell III; Harold E. Brooks; Gregory J. Stumpf; Erik Rasmussen (1999). "Highway Overpasses as Tornado Shelters: Highway Overpasses Are Inadequate Tornado Sheltering Areas". National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma. p. 6. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- "FEMA 342, Building Performance Assessment Team Report – Midwest Tornadoes of May 3, 1999" (PDF). Federal Emergency Management Agency. July 7, 1999. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- Nancy Mathis (2007). "A Tornado's Grip". Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado. Touchstone. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-7432-8053-2.

- Deadly Tornado Sends City Into Extreme Chaos | Critical Rescue S1 EP8 | Wonder on YouTube

- The World's Deadliest Tornadoes | Mega Disaster | Spark on YouTube

External links

- Doppler radar animation of the tornado (via YouTube)

- The Great Plains Tornado Outbreak of May 3–4, 1999 − a meteorological outline of the outbreak by the National Weather Service forecast office in Norman, Oklahoma

- FEMA: Oklahoma Tornadoes, Severe Storms, and Flooding