Iguala mass kidnapping

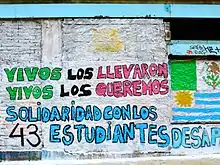

On September 26, 2014, forty-three male students disappeared from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers' College after being forcibly abducted in Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico. They were allegedly taken into custody by local police officers from Iguala and Cocula in collusion with organized crime. The mass kidnapping has caused continued international protests and social unrest, leading to the resignation of Guerrero Governor Ángel Aguirre Rivero in the face of statewide protests on October 23, 2014.

| 2014 Ayotzinapa (Iguala) mass kidnapping | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Mexican drug war | |

Poster issued by the government of Guerrero | |

| Location | Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico |

| Coordinates | 17°33′13″N 99°24′37″W |

| Date | September 26, 2014 21:30 – 00:00 (Central Standard Time) |

Attack type |

|

| Deaths |

|

| Injured | 25 |

| Victims | 43 (disappeared) |

| Perpetrators | Guerreros Unidos, Iguala and Cocula policemen, Mexican Federal Police (alleged), Mexican Army (alleged) |

| Motive | Unknown |

The students had annually commandeered several buses to travel to Mexico City to commemorate the anniversary of the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre; police attempted to intercept several of the buses by using roadblocks and firing weapons. Details remain unclear on what happened during and after the roadblock, but the government investigation concluded that 43 of the students were taken into custody and were handed over to the local Guerreros Unidos ("United Warriors") drug cartel and probably killed. This official version from the Mexican government is disputed. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) assembled a panel of experts who conducted a six-month investigation in 2015. They stated that the government's claim that the students were killed in a garbage dump because they were mistaken for members of a drug gang was "scientifically impossible".

Mexican authorities also claimed that José Luis Abarca Velázquez, the mayor of Iguala and a member of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), masterminded the abduction with his wife, María de los Ángeles Pineda Villa, as they wanted to prevent them from disrupting campaign events held in the city, although neither of them were put on trial for the students' disappearance. Both fled after the incident, were arrested about a month later in Mexico City for the murder of activist Arturo Hernández Cardona. Iguala's police chief, Felipe Flores Velásquez, was also arrested in Iguala on October 21, 2016.[1]

On November 7, 2014, Mexican Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam gave a press conference in which he announced that several plastic bags had been found by a river in Cocula containing human remains, possibly those of the missing students. At least 80 suspects have been arrested in the case, 44 of whom were police officers. Two students have been confirmed dead after their remains were identified by the Austria-based University of Innsbruck. Other sources have alleged a cover-up, stating that the 27th Infantry Battalion of the Mexican Army was directly involved in the kidnapping and murder. This is the case made by investigative journalist Anabel Hernández, claiming that two of the buses were secretly transporting heroin, without the students' knowledge. She stated that a drug lord ordered the battalion's colonel to intercept the drugs; the students, witnesses of the attack, were killed as collateral damage.[2][3][4] There are also reports linking federal forces to the case, some stating that military personnel in the area deliberately refrained from helping the students in distress.[5][4]

On December 3, 2018, newly elected President Andrés Manuel López Obrador announced the creation of a truth commission, to lead new investigations into the events.[6] In June 2020, José Ángel Casarrubias Salgado, known as "El Mochomo", leader of the United Warriors cartel, was arrested on suspicion of being responsible for the abductions and murders.[7][8] In September 2020, the government announced it was seeking the arrest in Israel and extradition of former official Tomas Zeron, one of the authors of the official "historical truth", which has been widely rejected by families of the students.[9] In August 2022, Jesús Murillo Karam was arrested over multiple charges (torture, forced disappearances, and offenses against the administration of justice) during his tenure as attorney general.[10][11] Later that month, the Truth Commission alleged that six of the students were held alive before being turned over to a local army commander, who ordered them to be killed.

Background

The Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers' College in Tixtla, Guerrero, Mexico, founded in 1926, is an all-male school that has historically been associated with student activism.[12] Guerrero teachers, including the students from Ayotzinapa, are known for their "militant and radical protests that often involve hijacking buses and delivery trucks."[13] The appropriation of vehicles was, according to the students, routine and temporary. Most of the buses are usually returned after the protests conclude. This tactic had largely been tolerated by law enforcement despite frequent complaints from owners and transport users.[14][15] Although federal agents have tended not to actively confront students for the appropriation of buses, the practice puts students and teachers at odds with local officials. Other protest tactics used by the students include throwing rocks at police officers, property theft and road blockings.[14][16]

Local authorities in Guerrero tend to be wary of student protests because of suspected ties with leftist guerrillas or rival political groups.[14] In 1995, the Guerrero state police killed seventeen farmers and injured twenty-one others during a protest in an event known as the Aguas Blancas massacre. The massacre led to the creation of the Popular Revolutionary Army (Spanish: Ejército Popular Revolucionario), which is believed by some state officials to retain some political influence in Guerrero.[17] Students claim to have no ties with such groups, and that the only thing they have in common with them is socialist ideology.[14] In addition, in Guerrero, where the bus companies are assumed to pay protection money, student campaigns are seen as threatening to organized crime.[15]

In December 2011, two students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa were gunned down and killed by the Guerrero state police during a rally on the Cuernavaca to Acapulco federal highway.[18]

In February 2013, President Enrique Peña Nieto published an education bill in the Official Journal of the Federation in agreement with the pact signed by the three main political parties, Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), National Action Party (PAN) and Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), named Pact for Mexico. The bill aimed to reform Mexican public education, introducing a competitive process for the hiring, promotion, recognition, and tenure of teachers, principals, and administrators and declared that all previous appointments that did not conform to the procedures were null.[19] Some teachers opposed the bill, claiming standardized tests that do not take in account the socio-economic differences between urban and under-equipped rural schools would affect students and teachers from economically depressed regions such as Guerrero.[20][21][22][23]

In May 2013, teachers belonging to the Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación (CNTE) union began rallies and strikes across Mexico, protesting in the Zócalo of Mexico City in a sit-in against the Reform and the bill of secondary laws.[24] Students of the Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa joined the protest against the reform.[25] In September 2013, the police retook the Zócalo square using water cannons and tear gas.[26]

Business organizations of Baja California,[27] Estado de Mexico,[28] and Chiapas[29] demanded decisive action against teachers on strike, as well as politicians from the PRD[30] and PAN,[31] and academics.[32] In October 2013, three teachers protesting against the Education Reform suffered head injuries and a broken arm after being pelted with stones. The attack was blamed on the inhabitants of the Tepito neighborhood, although teachers blamed the Federal Government.[33]

In January 2014, the governor of the State of Mexico, Eruviel Ávila Villegas, sent a bill to the local Congress proposing to sanction those teachers who were actively protesting and not attending their jobs with fines and jail time.[34] In August 2014, journalist Carlos Loret de Mola claimed to have heard a person in a meeting with President Peña Nieto saying "we're going to beat the hell out of the CNTE guys" ("Les vamos a partir la madre a los de la CNTE").[35]

Clash with authorities

On September 26, 2014, at approximately 6:00 p.m. (CST),[36] more than 100 students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers' College in Tixtla, Guerrero, traveled to Iguala, Guerrero, to commandeer buses for an upcoming march in Mexico City.[37][38][39]

The students had previously attempted to make their way to Chilpancingo, but state and federal authorities blocked the routes that led to the capital.[40] In Iguala, their plan was to interrupt the annual DIF conference of María de los Ángeles Pineda Villa, local President of the organization and the wife of the Iguala mayor.[41] The purpose of the conference and after-party was to celebrate her public works,[42] and to promote her campaign as the next mayor of Iguala.[43] The student-teachers also had plans to solicit transportation costs to Mexico City for the anniversary march of the 1968 student massacre in Tlatelolco.[44] However, on their way there, the students were intercepted by the Iguala municipal police force at around 9:30 pm, reportedly on orders of the mayor.[45][46]

The details of what followed during the students' clash with the police vary. According to police reports, the police chased the students because they had hijacked three buses and attempted to drive them off to carry out the protests and then return to their college. Members of the student union, however, stated that they had been protesting and were hitchhiking when they clashed with the police.[47] As the buses sped away and the chase ensued, the police opened fire on the vehicles. Two students were killed in one of the buses, while some fled into the surrounding hills. Roughly three hours later, escaped students returned to the scene to speak with reporters. In a related incident, unidentified gunmen fired at a bus carrying players from a local soccer team, which they may have mistaken for one of the buses that picked up the student protestors.[47][48] Bullets struck the bus and hit two taxis. The bus driver, a football player, and a woman inside one of the taxis were killed.[49][50] The next morning, the authorities discovered the corpse of a student, Julio César Mondragón, who had attempted to run away during the gunfire.[51] He was tortured before dying of brain injuries.[52] In total, 6 people were killed and 25 wounded.[53]

Kidnapping

After the shootings, eyewitnesses said that students were rounded up and forced into police vehicles.[54] Once in custody, the students were taken to the police station in Iguala and then handed over to the police in Cocula.[55] Cocula deputy police chief César Nava González then ordered his subordinates to transport the students to a rural community known as Pueblo Viejo.[56] At some point, while still alive, the students were handed over by the police to members of the Guerreros Unidos ("United Warriors"), a criminal organization in Guerrero (splintered from the Beltran Leyva cartel).[57] One of the trucks used to transport the students was owned by Gildardo López Astudillo (alias "El Cabo Gil"), a high-ranking leader of the gang.[56][58] "El Gil" then called Sidronio Casarrubias Salgado, the top leader of Guerreros Unidos, and told him that the people he had in custody posed a threat to the gang's control of the area.[59] Guerreros Unidos likely believed that some of the students were members of a rival gang known as Los Rojos.[60][61] With that information, Casarrubias allowed his subordinates to kill the students.[62] Investigators believe that a gang member known by his alias "El Chucky" or "El Choky" took part in the killings.[63] He was suspected of collaborating with Francisco Salgado Valladares, one of Iguala's security chiefs, in kidnapping the students.[64]

According to investigators, the students were taken to a dumpster in the outskirts of Cocula.[54] After reaching the site it is likely that 15 students had died of suffocation and the other students were then killed by Patricio Reyes Landa, Jonathan Osorio Gómez and Agustín García Reyes.[65][66] These three suspects then dumped the bodies in a pit, and some other suspects known only by their aliases burned the corpses with diesel, gasoline, tires, wood and plastic.[67] They also destroyed the students' clothing in order to erase all possible evidence. The fire most likely lasted from midnight until 2:00 or 3:00 pm. The gang assigned guards throughout the day to make sure that the fire was kept alive. When the fire had gone down, the suspects threw dirt in to cool the pit. They then placed the remains in eight plastic bags and dumped them in the San Juan river in Cocula, reportedly on orders from a man known only as "El Terco".[67][68] "El Gil" then sent a text message to Casarrubias Salgado confirming the completion of the task. "We turned them into dust and threw their remains in the water. They [authorities] will never find them", the text read.[69] Initially, 57 students were reported missing;[70] fourteen of them, however, were located after it was found that they had returned to their families or had made it back safely to their college.[71] The remaining 43 were still unaccounted for. Student activists accused authorities of illegally holding the missing students, but Guerrero authorities said that none of the students were in custody. Believing that the missing students had fled through the hills during the shootings, authorities deployed a helicopter to search for them. The 43 students, however, were never found.[72]

The mass disappearance of the 43 students marked arguably the biggest political and public security crisis Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto had yet faced in his administration (2012–2018).[73][74] The incident drew worldwide attention and led to protests across Mexico, and international condemnation.[75][76] The resulting outrage triggered near-constant protests, particularly in Guerrero and Mexico City. Many of them were peaceful marches headed by the missing students' parents, who come from poor rural families. Other demonstrations turned violent, with protesters attacking government buildings.[77] Unlike other high-profile cases that have occurred during the Mexican Drug War (2006–present), the Iguala mass kidnapping resonated particularly strongly because it highlighted the extent of collusion between organized crime and local governments and police agencies.[78][79]

Initial arrests and investigations

On September 28, 2014, members of the Office of the General Prosecutor in Guerrero arrested 22 police officers for their involvement in the shooting and disappearance of the students.[80] Police chief and Iguala's Director of Public Security, Felipe Flores Velásquez, turned in firearms, police vehicles, time shifts information, and policemen involved in the incident to the Ministry of Public Security.[81] The state government said that the 280 municipal police officers in Iguala had been called in for questioning about the incidents. All but 22 of them were released without charge. State prosecutor Iñaky Blanco Cabrera stated that the 22 officers detained had used excessive or deadly force against the students.[82] The investigations concluded that 16 of the 22 police officers had used firearms against the students.[83] They were imprisoned at the state penitentiary Social Reintegration Center of Las Cruces in Acapulco, Guerrero.[84] A few days later they were transferred to the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 4 (also known as "El Rincón"), a maximum-security prison in Tepic, Nayarit, under aggravated murder charges.[85]

The Mayor of Iguala, Abarca, claimed in an interview on September 29, 2014, that he had no previous knowledge of the incident, and that he could not have been responsible because he was attending a conference and after-party when the clashes took place.[86] Following this he claimed to have left to dine with his family at a restaurant. He said he heard about the attack when his personal secretary called him and gave him the details. "After that, I was in constant communication [with the police], giving them orders to not fall for provocations", Abarca said.[87] He said he was not aware of the students that were missing or of the investigation.[88] He also pledged that he would not resign and agreed to cooperate if he was investigated.[89] That day, Abarca met with the former Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) President Jesús Zambrano Grijalva, who requested him to formally petition a resignation.[90] Moreover, one account stated that Abarca's wife María de los Ángeles Pineda Villa was last seen at Guerrero's Tourist Promotion Body (Protur) in Acapulco that day in a private meeting with State Governor Ángel Aguirre Rivero. Eyewitnesses reportedly saw Pineda "worried" and "in a hurry".[91]

On September 30, 2014, Abarca asked for a 30-day leave of absence which was granted by the Iguala city council. His absence came amid pressures from other members of his political party, the PRD, who asked him to resign in order to facilitate investigations.[92] Before the official session was over at the city council, federal agents arrived asking for Abarca, but he had already left.[93] Federal agents then raided the mayor's house because he had an order of appearance. Abarca was believed to have left Iguala with his wife and children.[94] Investigations concluded that he had left Guerrero but was still in hiding somewhere in Mexico. "We are looking for him in an ongoing investigation. We have people on him," said Tomás Zerón de Lucio, head of the Criminal Investigation Agency.

Rumors suggested that he had fled the country.[95] Felipe Flores Velásquez was also issued an order of appearance. However, Flores was not located.[96] At that time, Abarca still benefited from immunity under Mexican law,[97] which protects elected officials from prosecution unless they commit a serious crime.[98][99] In Abarca's case, he was protected from prosecution of common crimes, but not from federal charges.[100]

On October 18, 2014, it was revealed that Guerreros Unidos (United Warriors) gang leader Sidronio Casarrubias Salgado was arrested by Mexican authorities.[101] United Warriors members were suspected of being involved in the abduction and murder of the 43 students.[101] On June 24, 2020, Salgado's brother and replacement as United Warriors leader José Ángel Casarrubias Salgado was arrested.[7][8] By this point in time, it was believed that El Mochomo was in fact responsible for the disappearance of the students and also the one who also ordered their murders.[7][8] On September 26, 2020, arrest warrants were issued for more police and it was the first time arrest warrants were issued for soldiers as part of this investigation.[102]

Eight other cartel members were also arrested. The mayor of Iguala, José Luis Abarca, has been accused of direct participation in the earlier torture and murder of an activist; the mayor's wife, María de los Ángeles Pineda Villa, is the sister of known members of the Beltrán-Leyva Cartel.[103] The mayor and his wife, and the police chief, fled the area and were declared fugitives.[104] Protesters demanding justice for the victims marched in several cities.[105][106]

Aftermath

A number of theories have been proposed to explain the killing of the students. The students all attended a local teacher training college with a history of left-wing activism and radicalism, but it is not clear that they were targeted for their political beliefs. Some think that they angered Guerreros Unidos by refusing to pay extortion money. Others believe that there was a link between the students' disappearance and a speech given by the wife of Iguala's mayor on the day of the clashes. She was speaking to local dignitaries when the students were protesting in Iguala and some believe they were targeted because it was feared they could disrupt the event.[106]

A mass grave, initially believed to contain the charred bodies of 28 of the students, was discovered near Iguala on October 5, 2014.[107] They had been tortured and, according to reports, burned alive.[108] Subsequent reports increased the estimate of the number of bodies found to 34.[109]

On October 10, 2014, the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances; Christof Heyns, Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; and Juan E. Méndez, Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, released a joint statement calling the Iguala attacks a "crucial test" for Mexico's government. "What happened in Guerrero is absolutely reprehensible and unacceptable," the statement says. "It is not tolerable that these kind of events happen, and even less so in a state that respects the rule of law."[110]

On October 13, 2014, protesters ransacked and burned government offices in Chilpancingo, the capital of Guerrero, although the fire was controlled, it destroyed part of the history records of birth, marriages and deaths of Chilpancingo.[111][112][113]

On October 14, 2014, police announced that forensic tests had shown that none of the 28 bodies from the first mass grave corresponded to the missing students, but on the same day four additional graves, with an unknown number of bodies, were discovered.[114]

On October 20, 2014, masked protesters set fire to an office of a state social assistance program, Guerrero Cumple, in Chilpancingo, burning computers and filing cabinets. On the next day some 200 protestors set fire to the regional office of the Party of the Democratic Revolution in Chilpancingo which controls the state government.[115]

On October 22, 2014, the federal government stated that Abarca had ordered the arrest of the students in order to prevent them from obstructing a municipal event.[116] The PGR described him and his wife as the probable masterminds of the mass kidnapping. The director of the Iguala police force, Felipe Flores, was also mentioned as one of the main perpetrators.[117] The Mexican government discovered that a local cartel paid the police force US$45,000 monthly to keep them on the cartel payroll.[118]

In Mexico City over 50,000 protesters demonstrated in support of the missing students. Joining the protests in Morelia, Michoacán, were members of Mexico's movie industry – actors, directors, writers and producers- who lit 43 candles on the steps of a Morelia theater. In Venezuela, students also demonstrated in support at the Central University of Venezuela. In the U.S. state of Texas, students and professors rallied at the campus of the University of Texas at El Paso. The name of each disappeared student was read out and signatures were gathered for an open letter of protest to the Mexican consulate. Protests also took place in London, Paris, Vienna and Buenos Aires.[119]

On the same day in Iguala, dozens of protesters, many wearing masks, broke away from a peaceful march of thousands of people demanding that the missing students be returned alive, and broke into the city hall, shattered windows, smashed computers and set fire to the building.[115][120]

On October 23, 2014, the governor of Guerrero, Ángel Aguirre Rivero, asked Congress for a leave of absence in order to step down from office.[121] According to Mexican law, state governors cannot resign but may ask for a leave of absence;[122] though an uncommon decision in Mexico at the time, Aguirre decided to leave his post, pressured by his party and public opinion.[123] State lawmakers voted to replace Rivero with Rogelio Ortega Martínez, who served until October 2015.[124]

On October 27, 2014, the authorities arrested four members of Guerreros Unidos; according to officials, two of them received a large group of people from other gang members in Iguala on the night the mass abduction took place. Their testimonies helped the authorities locate new mass graves in Cocula, Guerrero, about 17 km (10 mi) from Iguala.[125] The area was cordoned off by the Mexican Army and Navy before the forensic teams arrived to carry out their investigations.[126]

On October 29, 2014, a few hours after being appointed as the interim mayor of Iguala, Luis Mazón Alonso asked for a leave of absence.[127] He said in an interview that he had decided to resign because some members of the Iguala city council were self-serving and had no interest in improving the situation.[128] He is the brother of Lázaro Mazón Alonso, the former Secretary of Health in Guerrero, who resigned on October 16, 2014, after the former Governor Aguirre accused him of being linked to Abarca.[129][130] Silviano Mendiola Pérez became the interim mayor of Iguala on November 11.[131]

On November 9, 2014, there was a demonstration in Mexico City during which the protesters carried handmade banners with the words "Ya me cansé" ("I've Had Enough" or "I'm Tired"), in reference to a comment made by Mexico's attorney general, Jesús Murillo Karam, at a press conference on the Iguala kidnapping.[132] Protesters also chanted: "Fue el Estado" ("It was the State"). Some masked protesters broke away from the otherwise peaceful demonstration as it drew to a close, tore down the protective metal fences set up around the National Palace in Mexico City's main Zócalo plaza and set fire to its imposing wooden door. Clashes with riot police followed.[133]

On November 20, 2014, relatives of 43 missing Mexican students arrived in Mexico City after touring the country and led mass protests demanding action from the government to find them. Thousands of people took part in three protest marches in the capital. Demonstrators called for a nationwide strike. Several hundred protesters gathered near the National Palace, small groups of protesters were throwing bottles and fireworks at the palace and the police tried to push them back using water cannons. Near Mexico City International Airport before the marches began some 200 hooded protesters threw rocks and petrol bombs at police officers who had been trying to disperse them. Protests also took place in other parts of Mexico and abroad. Mexican President Peña Nieto accused some of the protesters of trying to "destabilize" the state.[134]

The Union of Towns and Organizations of Guerrero (UPOEG), along with activists, parents of the missing students, and other drug war victims from different parts of Mexico, organized and led a search in Iguala on November 23 to uncover more bodies buried in the municipality's clandestine mass graves. They uncovered seven bodies in mass graves at a rural community known as La Laguna. The purpose of the search was to locate mass graves for federal authorities to investigate. "We are doing the job authorities are refusing to do", one of the activists said.[135] Locals stated that members of organized crime frequented the area to bury people around there.[136] The following day, the PGR arrived at Iguala to recover the bodies and investigate them. They planned to further their investigations on the mass graves found by the UPOEG. Those present told federal authorities to not allow local officials to intervene in the case.[137] The UPOEG announced that they would be leading a committee to uncover more mass graves in Guerrero.[138] Bruno Plácido Valerio, the leader of the group, stated that from January 2013 to November 2014, at least 500 bodies were located between Ayutla and Iguala. He believes that there are more bodies buried in mass graves all across the state.[139]

On December 3, 2014, Javier Hernández Valencia, the Representative in Mexico of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights[140] visited the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College in Ayotzinapa, and met with the parents of the missing students, other student survivors and activists accompanying their struggle.[141] The resultant public report "Double injustice"[142] is an independent inquiry focused on key aspects of the official investigation under the light of applicable international human rights standards, including the blatant evidence of arbitrary detentions and torture on 51 people indicted in connection to the crime. Although the report explicitly states it does not intend to offer an alternate version of facts nor to identify the perpetrators and their sponsors, it sheds light on the deliberate actions attributable to the PGR to produce "quick results" and solve the crime, which ultimately tainted the investigation itself.

On January 12, 2015, relatives and supporters of the missing students tried to gain access to an army base in Iguala. The protesters demanded to be let in to search for the missing students. They accused the security forces of colluding in their disappearance. They said soldiers had witnessed a clash between the students and local police which immediately preceded their disappearance, and reportedly failed to intervene.[143]

On January 26, 2015, after the confession of one of the men who plotted against the students had been finalized, Mexican officials took it to the media to inform the country that the 43 students had been killed and their remains were burned.[144]

On February 13, 2015, a delegation of parents who traveled to Geneva, Switzerland, with support from a coalition of human rights NGOs, attended the public hearing of the United Nations Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED), a body of independent experts which monitors the implementation of the Convention for the Protection of all Persons against Enforced Disappearance by the States parties, and submitted the case of the killing and disappearances of their loved ones to the specialized international watchdog panel,[145] further raising international media attention to their plight.[146][147]

On February 27, Attorney General Murillo Karam left his post at the PGR. He was replaced by Arely Gómez González.[148]

On May 7, Francisco Salgado Valladares, the deputy police chief of Iguala, was arrested by the Federal Police in Cuernavaca, Morelos. He was wanted for his alleged involvement in intercepting the students on their way to Iguala.[149] According to law enforcement reports, Salgado Valladares had connections with the Guerreros Unidos gang and reportedly received bribes from them to hand out to other members of the police corporation.[150] At the time of his arrest, he was one of the most-wanted suspects in the case.[151]

Arrest of Abarca and Pineda

At around 2:30 a.m. (CST) on November 4, 2014,[152] an elite squadron of the Federal Police arrested former Iguala mayor Abarca and his wife Pineda at a house in the Tenorios neighborhood in Iztapalapa, Mexico City.[153][A 1] Neither of them resisted arrest.[155] Abarca confessed that he was tired of hiding and that the pressure was too much for him. His wife, on the other hand, showed her disdain for law enforcement.[156][157] The arrest was confirmed through Twitter by the Federal Police spokesperson José Ramón Salinas early that morning.[158] Once in custody, they were taken by law enforcement to the federal installations of SEIDO, Mexico's anti-organized crime investigation agency, for their legal declaration.[159] At the time of their arrest, Abarca and Pineda were among Mexico's most-wanted.[160][161]

In addition to Abarca and Pineda, another person was arrested by the authorities that day in Santa María Aztahuacán, Iztapalapa. Federal agents stated that the individual was Noemí Berumen Rodríguez, who was believed to have aided the couple in their hiding by lending them her house.[162][163] She is a friend of the couple's 25-year-old daughter Yazareth Liz Abarca Pineda, who was taken into custody along with her parents. However, Yazareth was only considered an eyewitness and does not face criminal charges. Authorities were able to link Berumen with the Abarcas due to her friendship with Yazareth and her presence on social media. They discovered that Yazareth had a picture with a friend that lived in Iztapalapa, who followed Berumen online.[164][165]

When the Abarcas left Iguala after the mass kidnapping in September 2014, law enforcement began an investigation to locate all the properties owned by the couple and their families.[166] Abarca had several properties in Guerrero and in other states, but authorities believed that he was hiding in Mexico City or Monterrey, Nuevo León.[A 2] After ruling out Monterrey as a possible hideout, authorities concentrated on three properties in Iztapalapa where they believed the couple was hiding.[169][170] Through the couple's real estate businesses, authorities were also able to link Berumen to the family once more and locate her properties in Iztapalapa.[171] In one of the properties, investigators noticed something unusual: they regularly saw a woman (now known to be Berumen) going in and out of a property that was thought to be abandoned. Authorities then mounted an investigation and surveillance operation on Berumen before finally entering the property and arresting Abarca and Pineda.[170]

At 5:10 p.m. on November 5, 2014, Abarca was transferred to the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1 (commonly referred to as "Altiplano"), a maximum-security prison in Almoloya de Juárez, State of Mexico.[172] He was imprisoned for his pending homicide charge, organized crime, and forced disappearance charges.[173] A judge ordered for Pineda to remain under federal custody for 40 days in order to gather more evidences against her.[174] On December 15, her federal custody detention was extended to 20 more days.[175] She was sent to the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 4 in Nayarit state on January 4, 2015.[176] Berumen was bailed from prison a few days after her arrest.[177]

Iguala police chief at the time of the kidnapping, Luis Antonio Dorantes Macías, was sentenced to prison on January 24, 2021, for his involvement in the incident.[178]

Attorney General's conference with family

On November 7, 2014, the family members of the missing students had a conference in the military hangar in Chilpancingo National Airport with the Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam.[179] In the meeting, authorities confirmed to the families that they had found several bags containing unidentified human remains. According to investigators, three alleged members of the Guerreros Unidos gang, Patricio Reyes Landa (alias "El Pato",) Jonathan Osorio Gómez (alias "El Jona",) and Agustín García Reyes (alias "El Chereje",) directed authorities to the location of the bags alongside the San Juan river in Cocula.[65][180] Murillo Karam stated that the three suspects admitted to having killed a group of around 40 people in Cocula on September 26, 2014. The suspects stated that once the police handed over the students to them, they transported them in trucks to a dumping ground just outside town. By the time they got there, 15 students had died from asphyxiation. The remaining students were interrogated and then killed.[181][182] The suspects dumped the bodies in a huge pit before fueling the corpses with diesel, gasoline, tires, wood and plastic. To destroy all evidence, the suspects also burned the clothing the students had on them. The fire lasted from midnight to around 2:00 and 3:00 p.m. the next day. Once the fire had subsided, the suspects returned to the site and threw dirt and ashes to cool down the remains. They then filled up eight plastic bags, smashed the bones, and threw them in the river on orders from a Guerreros Unidos member known as "El Terco".[183]

At the press conference, Murillo Karam showed a video re-enactment of how the bodies were transported,[184] and several video interrogations of the suspects, and also video of teeth and bones recovered at the site.[185] He said that the remains were badly burned, making DNA identification difficult. In order to properly identify the remains, the federal government turned to a team of internationally renowned forensic specialists from the University of Innsbruck in Austria for help, though he said there was no definite timeframe for the results.[186] The families of the students, however, did not accept the statements of the Attorney General and continue to believe that their sons are still alive. They said that they will not accept that their children are dead until it is proven scientifically by independent investigators, since they fear that the government is attempting to close the case in order to counter public outrage.[187] Murillo Karam stated that 74 people had been arrested since the case started and another 10 had arrest warrants.[188] He said that until the situation of the students is confirmed, the case remains open and the government formally considers the students "disappeared".[189]

Murillo Karam was arrested on August 19, 2022, in Mexico City and charged with "forced disappearance, torture and obstruction of justice".[190]

Resignation of the PRD founder

After meeting with the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) president Carlos Navarrete Ruiz and secretary-general Héctor Miguel Bautista López on November 25, 2014, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, the party's founder and senior leader, resigned and issued a letter explaining his departure.[191] A three-time presidential candidate, Cárdenas stated that he had old differences with other party leaders in how to tackle the internal problems of the PRD and on how to help it restore credibility.[192] Days earlier, he had called for all of the national executive committee of the PRD, Navarete and Batista included, to resign for failing to reform the party.[193] According to Cárdenas, the PRD, which governs Guerrero state and the city of Iguala, was on the verge of dissolution following the political crisis caused by the mass disappearance of the 43 students. The alleged mastermind of the abductions, Jose Luis Abarca Velásquez, was a member of the PRD.[194][195] The incidents in Iguala caused arguably one of the biggest political crisis the PRD and Mexico's political left had faced since the party's formation in 1989.[196][197] When Abarca was linked to the disappearances, many top politicians who had supported his campaign as mayor distanced themselves from him.[198] But many of them also pointed fingers at each other, arguing that some members of the PRD were allied to Abarca.[199]

Identification of the students

On December 6, 2014, the first of the 43 missing students, Alexander Mora Venancio (aged 19), was confirmed dead by forensic specialists at the University of Innsbruck. Specialists were able to confirm the status of Mora Venancio by comparing his bone fragments with the DNA samples the laboratory had of his father Ezequiel Mora Chavez and his brothers Omar and Hugo Mora Venancio.[200] The news was first made public by the student committee of the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers' College of Ayotzinapa on the school's Facebook page, and the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF) notified the parents of the student on the status of their son.[201][202] The committee claimed that the human remains of Mora Venancio were among those located in Cocula, Guerrero.[203] Mexican authorities confirmed the reports the following day at a press conference and released a 10-page report from Dr. Richard Scheithauer, head of the Institute for Legal Medicine at University of Innsbruck, confirming Mora Venancio's status. Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam stated that at least 80 people had been arrested in the case, and that 44 of them were policemen of Cocula and Iguala. He said that 16 police officers from these two municipalities were still being sought, along with 11 other probable suspects.[204] After the announcement, classmates, family members, and people close to Mora Venancio paid their respects at his home in Tecoanapa, Costa Chica, Guerrero.[205] The state of Guerrero declared a three-day mourning for his death.[206] In Mexico City, marches led by the students' family members intensified with the confirmation of Mora Venancio's death.[207][208] "This day of action will continue until we find the remaining 42 alive", the group's spokesperson said in front of thousands of protestors gathered at the Monumento a la Revolución landmark.[209]

On September 16, 2015, the remains of Jhosivani Guerrero de la Cruz were identified.[210] The remains of Mora Venancio were also reconfirmed in the tests.[211]

In July 2020, it was announced that bone fragments found near the location from where the students had disappeared had been tested at the University of Innsbruck and identified as the remains of Christian Alfonso Rodríguez Telumbre (aged 19). An anonymous call led investigators to a specific spot in Cocula, a town near Iguala, where the remains were found — about half a mile from the garbage dump.[212]

Global Action for Ayotzinapa

The massacre sparked protests worldwide. The protests began to take place after the formal arrest of former Iguala mayor Jose Luis Abarca and his wife Maria de Los Angeles on November 4, 2014.[213] Global action has not only been manifested through protests, but also via online support. #YaMeCansé, #FueElestado, #TodosSomosAyotzinapa, and #AccionGlobalPorAyotzinapa are amongst the most popular hashtags which allow users to express their thoughts via Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.[214]

Relatives of the missing 43 students toured the United States in April 2015 to raise awareness of the events that took place in Iguala. Known as the Caravana 43, the tour was organized in conjunction with a national coalition of social activist groups seeking justice for Ayotzinapa.[215] The tour of 14 parents, students, and advocates was split into three groups that covered eastern, middle, and western regions of the United States, stopping in a total of 43 cities over 19 states before convening for a march to the United Nations Headquarters in New York City.[215] Caravana 43 claimed no connection to any official political party or national organization. Instead, its organization was completely voluntary with transportation and accommodations for the relatives covered entirely by donations from individuals in host cities. Local groups "committed themselves to support the fundamental goal of providing a platform for the parents in the United States and assumed the organizational and financial responsibility for the Caravan."[215] By creating the opportunity for the relatives to travel throughout the United States, organizers hoped to better inform the American public and new media about the attacks and disappearances. In each of the host cities, relatives spoke not only of their loss, but also of the systematic violence and impunity committed by the Mexican government and its police. Official statements from the tour affirm "The problem is Mexico has a long history documented by Mexican and foreign human rights organizations, other governments, and international organizations of using torture to extract confessions which are then used to construct narratives to protect criminals, the police, military officers, government officials, and politicians ... Consequently, many people have no faith in the government's account and have demanded that the investigations continue."[215] Relatives met with students, teachers, and laborers, pleading for the United States to intervene in the crisis. Moreover, the relatives asked elected officials to rethink U.S. foreign policy as it pertains to Mexico, specifically in regards to the Mérida Initiative.[216] Many believe that these funds are being used to suppress the people, rather than fight the drug cartels. Caravana 43 achieved relative success in the United States. After meeting with the groups, several legislators voiced public support for their effort. Cristina Garcia, a California Assembly member stated, "It's a human rights violation that's been going on and it affects a lot more than just these students... [The state] has the responsibility to affect change with our border country."[216] Crowds were gathered at each stop and thousands of people joined in social media platforms to promote the tour. The project served as a unifying mechanism not only across international borders, but also for Latino communities within the United States.[215] Following the end of Caravana 43 in the U.S., the parents, students, and advocates hope to continue in their search for truth by organizing similar tours across South America and Europe.

Nobel Prize Awards protest

A young Mexican man interrupted Malala Yousafzai's Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony in a protest over the Iguala kidnapping, but was quickly taken away by the awards security personnel. Yousafzai later sympathised, and acknowledged that problems are faced by young people all over the world, saying "there are problems in Mexico, there are problems even in America, even here in Norway, and it is really important that children raise their voices."[217]

Allegations of federal police and army involvement

Proceso magazine has implicated the involvement of the Mexican Federal Police and Mexican Army in the case in a December 2014 report.[218][219]

Although President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has promised complete transparency in the investigation, El País reported on December 17 that since the November 2020 arrest of an army captain, the Mexican army has not cooperated in the investigation.[220]

On August 26, 2022, Mexican Interior Undersecretary Alejandro Encinas, leader of the Truth Commission, announced that six of the 43 students were allegedly kept alive in a warehouse for days, and then turned over to a local army commander, Colonel José Rodríguez Pérez, who ordered them to be killed.[221][222]

2015 investigation

In September 2015, the results of a six-month investigation by a panel of experts assembled by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights became known to the public. The investigation concluded that the government's claim that the students were killed in a garbage dump because they were mistaken for members of a drug gang was "scientifically impossible" given the setting's conditions.[223] But other experts, however, criticized this investigation for its shortcomings and stated that it was possible for the missing students to have been killed at the dump.[224][225] The government responded to the report by stating that they would carry out a new investigation and a second opinion from other renowned experts to determine what happened the night the students were probably killed.[226]

In July 2017, the international team assembled to investigate the Iguala mass kidnapping publicly complained they thought they were being watched by the Mexican government.[227] They claim that the Mexican government utilized Pegasus, software developed by NSO Group, to send them messages about funeral homes that contained links which, when clicked, granted the government the ability to surreptitiously listen to the investigators.[227] The Mexican government has repeatedly denied any unauthorized hacking.[227]

Witnesses

An eyewitness who was provided with witness protection by the Mexican Human Rights Commission testified in April 2016 about the involvement of the army and a drug leader known as "El Patrón".[228]

A report from Sputnik news agency says that Roman Catholic priest and human rights activist Alejandro Solalinde said in May 2016 that he had interviewed seven witnesses, one of which insisted that the army was involved.[229]

Jan Jařab of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Mexico condemned the torture of Carlos Canto and 33 other witnesses after a video was released on June 21, 2019.[230]

Bernabé García, a key witness in the case, was given asylum in the United States by an Arizona judge in February 2020.[231]

Ezequiel Peña Cerda, area director of the Criminal Investigation Agency (AIC), was charged for torturing suspects in the Ayotzinapa case on March 17, 2020.[232]

Pablo Morrugares, a journalist for PM Noticias who specialized in drug-related crime, was working the evening of September 26–27 and reported that he had clear evidence of military involvement in the attack on the students. Morrugares was murdered on August 2, 2020.[233]

On September 28, 2020, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) said that he wanted to place all the people who were recently arrested into a witness protection program.[234] "It is also being sought that the detainees can be considered as protected witnesses because there was a pact of silence so that they did not speak and that pact of silence must be broken," he said.[235]

General Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, former Secretary of National Defense (SEDENA) (2012–2018) was exonerated on charges of ties to drug traffickers on January 14, 2021. Cienfuegos defended the refusal of the armed forces to participate in investigations into human rights violations in this case or in the Tlatlaya massacre in Michoacan in July 2014 wherein 22 civilians were killed by soldiers.[236] Cienfuegos was arrested on drug trafficking charges in Los Angeles, California, on October 16, 2020,[237] The government of Mexico was widely criticized for releasing Cienfuegos.[238][239][240]

Tomás Zerón, exdirector of the former AIC, seeks asylum in Israel after being accused of hiding evidence and torture in the Ayotzinapa case.[241][242]

Juan Carlos Flores Ascencio, "La Beba", alleged leader of Guerreros Unidos a drug gang implicated in the case, was murdered on January 17, 2021.[243] Two members of Guerreros Unidos in Chicago were identified in September 2019 as witnesses in the Ayotzinapa case.[244]

Reforma reported on January 21, 2021, that "Juan", a presumed drug gang member, alleged soldiers held and interrogated some of the students before turning them over to a drug gang. The witness said that an army captain, who is now facing organized crime charges in the case, held some of the students at a local army base and interrogated them, before turning them over to the Guerreros Unidos drug gang. The Interior Department confirmed that the testimony was part of the case file and said it would file charges against whoever leaked it.[245] Family members of the victims say they believe leaks about the identities of witnesses are carried out with the intention of protecting the army.[246]

See also

- 2021 Pantelhó mass kidnapping

Notes

- Preliminary reports mistakenly reported that the arrest of the couple was made in a different neighborhood, Santa María Aztahuacán.[154]

- On October 23, 2014, rumors circulated that Abarca was arrested in Boca del Río, Veracruz. The government later confirmed that the rumors were false.[167] Another version stated that the couple had stayed in Puebla with some friends, and that they were eventually arrested in Xalapa, Veracruz. That version turned out to be false too.[168]

References

- "Mexico missing students: Ex-police chief in Iguala arrested". BBC News. October 21, 2016. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- "Iguala: la historia no oficial – Proceso". Proceso.com.mx. December 14, 2014. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- What Happened To Mexico's Missing 43 Students In 'A Massacre In Mexico' Archived November 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine on NPR

- "Testimonio: sobreviviente de la masacre a estudiantes de Ayotzinapa". Vanguardia.com.mx. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- "Militares del 27 Batallón interceptan y amenazan a normalistas de Teloloapan – Proceso". Proceso.com.mx. November 19, 2014. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- "Mexico's new president forms truth commission on missing students". Archived from the original on April 25, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- "el-mochomo-falls-allegedly-involved-in-the-disappearance-of-the-43-from-ayotzinapa/". explica.co. Archived from the original on July 2, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Detienen a 'El Mochomo', operador de los Guerreros Unidos". El Universal. June 29, 2020. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Mexico asks Israel to detain ex-investigator in student case". Yahoo! News. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- Verza, Maria. "Mexico arrests ex-attorney general in case of 43 missing students, who disappeared in 2014". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 22, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- "Mexico arrests ex-attorney general in 2014 case of 43 missing students". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on August 22, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- Lewis, Ted (October 22, 2014). "Mexican Government – Tell Us the Truth – Where are the Ayotzinapa 43?". HuffPost. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Rivera, José Antonio (October 5, 2014). "Mexican officials fear mass grave holds remains of 43 student protesters allegedly 'slaughtered' by local police". National Post. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Villegas, Paulina (November 2, 2014). "Keeping Mexico's Revolutionary Fires Alive". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Miroff, Nick (October 11, 2014). "Mass kidnapping of students in Iguala, Mexico, brings outrage and protests". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 18, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Fearing for the rule of law in Mexico". San Antonio Express-News. November 1, 2014. Archived from the original on November 16, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- (subscription required) de Córdoba, José (October 2, 2014). "Mexico Searches for 43 Missing Students in Violent Guerrero State". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 2, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Matan policías a dos estudiantes al desalojar un bloqueo carretero". La Jornada (in Spanish). December 12, 2011. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- Improving education in Mexico: A state-level perspective from Puebla. OECD. 2013. p. 58. ISBN 978-92-64-20019-7. Archived from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- "Reforma educativa pega a maestras rurales". Cimac Noticias. September 17, 2013. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- C.V, DEMOS, Desarrollo de Medios, S. A. de (August 29, 2015). "La Jornada: No es capricho el rechazo a la reforma educativa, afirman docentes y directores". jornada.com.mx. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- "En fotos: la pobreza de las escuelas rurales en México – BBC Mundo". BBC. November 27, 2013. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- "Calidad educativa en las comunidades rurales de México". Sinembargo.mx. July 17, 2015. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- IFE. "Reforma Educativa 2012––2013" (PDF) (in Spanish). IFE. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Rolando Aguilar (October 14, 2014). "Normalistas y comunitarios marchan en Ayotzinapa" (in Spanish). Excelsior. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Jo Tuckman (September 14, 2013). "Mexican riot police end striking teachers' occupation of city square". The Guardian.

- AFN (October 24, 2013). "Empresarios: "Mano dura" contra maestros". AFN Tijuana. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Juan Manuel Barrera (August 29, 2013). "Empresarios piden Mano Dura contra Maestros de las CNTE". El Universal. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- El orbe (March 6, 2013). "Mano Dura contra Maestros Faltistas". El Orbe. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Andrea Becerril; Victor Ballinas (April 26, 2013). "Aplicar 'mano dura' contra maestros de Guerrero, estima Graco Ramirez". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Tania Sanchez Hernandez (January 7, 2014). "Mano dura, pide Federico Döring (PAN)". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Abraham Espinoza (October 10, 2013). "Gobierno federal debe aplicar 'mano dura' a profesores de la CNTE" (in Spanish). Oro Noticias. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- "Comerciantes de Tepito atacan a maestros; la CNTE culpa al gobierno de la agresión". La Jornada (in Spanish). October 18, 2013. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- Ma Teresa Montaño (January 15, 2014). "Eruviel Planteará carcel para Maestros Faltistas". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Carlos Loret de Mola (August 12, 2014). "Les vamos a partir la madre". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- "Policías atacaron a normalistas sin motivo y un comandante amenazó: 'los voy a venir a levantar'" (in Spanish). El Sol de Acapulco. October 13, 2014. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- "Mexico: How 43 Students Disappeared In The Night". Theintercept.com. May 4, 2015. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- "Testimonio sobre ataque a normalistas de Ayotzinapa (03/18/2015)". Lacartita.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- "Ayotzinapa Report" (PDF). Media.wix.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- Cano, Arturo (October 25, 2014). "'La justicia no va a llegar, aunque la busquemos,' lamentan en Ayotzinapa". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "Abarca y Pineda, la 'narcopareja' que gobernó Iguala". El Universal (in Spanish). Red Política. October 22, 2014. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- Cepeda, César (October 10, 2014). "La reina de Iguala" (in Spanish). Reporte Índigo. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "El alcalde de Iguala y su esposa, vinculados a los Beltrán Leyva" (in Spanish). Aristegui Noticias. October 7, 2014. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- McGahan, Jason (October 8, 2014). "Anatomy of a Mexican Student Massacre". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "Lo que ocurrió el 26 de septiembre en Iguala, según PGR". El Universal (in Spanish). Red Política. October 23, 2014. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- "Policía de Iguala disparó a normalistas; reporta PGJ seis muertos por ataques". Proceso (in Spanish). September 27, 2014. Archived from the original on September 29, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "Mexican students missing after protest in Iguala". BBC News. September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- Sullivan, Gali (October 6, 2014). "Charred bodies found in 'the land of the wicked' may be missing Mexican students". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "Dos balaceras dejan 6 muertos y 17 heridos en Iguala, Guerrero" (in Spanish). El Sol de Acapulco. Organización Editorial Mexicana. September 28, 2014. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "Student protests in central Mexico leave 43 missing, 6 dead and 22 cops arrested". Fox News. September 30, 2014. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "La esposa de uno de los estudiantes muertos en Iguala cuenta su historia" (in Spanish). Univision. October 6, 2014. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "Classmate of 43 missing Mexican students was tortured, report says". The Guardian. July 12, 2016. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- Pineda, Leticia (October 6, 2014). "Mexico leader vows justice over 43 missing students". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- Laccino, Ludovica (October 22, 2014). "Mexico's 43 Missing Students: Theories Behind Mysterious Disappearance". International Business Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Mexico: Mayor linked to deadly attack on students". USA Today. Associated Press. October 23, 2014. Archived from the original on November 19, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- Ross, Oakland (October 30, 2014). "A Mexican massacre and the Queen of Iguala". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Mexico catches chief of gang in missing students case". The Daily Telegraph. October 18, 2014. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Macabras declaraciones" (in Spanish). Reporte Índigo. November 7, 2014. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- Castillo, Gustavo (October 22, 2014). "Señala PGR a Abarca y su esposa como autores intelectuales del ataque en Iguala". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Indagan nexo cártel-normalistas". El Mañana (in Spanish). October 29, 2014. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Vicenteño, David (October 26, 2014). "Un mes, 52 detenidos y todavía no aparecen" (in Spanish). Excélsior. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Tuckerman, Jo (October 23, 2014). "Mexican mayor and wife wanted over disappearance of 43 students". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "28 cuerpos, los encontrados en fosas clandestinas de Iguala" (in Spanish). CNNMéxico. Turner Broadcasting System. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on October 8, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Mosendz, Polly (October 6, 2014). "A Mass Grave Points to a Student Massacre in Mexico". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Garcia, Jacobo G. (November 7, 2014). "Families of missing students told of new remains". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "Yo participé matando a dos de los ayotzinapos, dándoles un balazo en la cabeza..." (in Spanish). Zócalo Saltillo. October 24, 2014. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Palabras del procurador Jesús Murillo Karam, durante conferencia sobre desaparecidos de Ayotzinapa". La Jornada (in Spanish). November 7, 2014. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- "Mataron y quemaron a '43 o 44' en Cocula" (in Spanish). Milenio. November 8, 2014. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- "Nunca los van a encontrar: 'El Gil'" (in Spanish). Milenio. November 11, 2014. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- "Autoridades de México buscan a 57 estudiantes desaparecidos" (in Spanish). CNN en Español. Turner Broadcasting System. September 27, 2014. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Temores y sospechas por misteriosa desaparición de normalistas en Iguala" (in Spanish). CNN México. Turner Broadcasting System. October 2, 2014. Archived from the original on October 2, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Mexican students missing after protest in Iguala". BBC News. September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- (subscription required) Dudley, Althaus (October 29, 2014). "Men Detained Over Missing Mexican Students". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- Rajo, Carlos (October 2014). "Iguala y los 43 estudiantes desaparecidos: la más grave crisis del gobierno mexicano" (in Spanish). Telemundo. NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Mosendz, Polly (October 17, 2014). "Protests Spread Across Mexico as More Mysterious Graves Are Found". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- Johnson, Tim (October 30, 2014). "In missing students case, Mexico draws world attention it doesn't want". Washington, D.C.: McClatchy DC Bureau. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- Tuckman, Jo (October 30, 2014). "Hunt for Mexico's missing students moves to rubbish dump". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- "Mexico officials search grave, arrest suspect in missing students case – LA Times". Los Angeles Times. October 28, 2014. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- Villegas, Paulina (October 28, 2014). "In Mexico, a New Lead on Missing Students". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- "Detienen a 22 policías municipales por balacera contra normalistas en Iguala". La Jornada (in Spanish). September 28, 2014. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- Badillo, Jesús (November 14, 2014). "Secretario de Seguridad de Iguala entregó a sus policías y se 'esfumó'" (in Spanish). Milenio. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- "22 Mexican police officers held in killings – LA Times". Los Angeles Times. September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- "Consignan a 22 policías de Iguala por presunto homicidio de 6 personas" (in Spanish). Animal Político. Elephant Publishing, LLC. September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Los 22 policías detenidos en Iguala son trasladados a Cereso de Acapulco" (in Spanish). Sin Embargo. September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Trasladan a Nayarit a policías involucrados en matanza de normalistas en Iguala" (in Spanish). Nayarit en Línea. October 12, 2014. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Alcalde de Iguala no supo de los ataques porque estaba en un baile". Proceso (in Spanish). September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "No supe de enfrentamientos, estaba en un baile: alcalde". El Universal (in Spanish). September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "Ordené a policías no caer en provocación: alcalde de Iguala" (in Spanish). Milenio. September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "No me enteré, estaba en un baile: alcalde" (in Spanish). El Debate (Mexico). September 30, 2014. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- "No ayudé a escapar a Abarca; es culpa de Iñaky Blanco: Zambrano" (in Spanish). Excélsior. October 29, 2010. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- García Soto, Salvador (October 27, 2014). "Serpientes y Escaleras". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- "Alcalde de Iguala pide licencia después de asesinatos cometidos por la policía" (in Spanish). Animal Político. September 30, 2014. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- Esteban, Rogelio Agustín (September 30, 2014). "Alcalde de Iguala pide licencia" (in Spanish). Milenio. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- Ambrosio, Natividad (October 1, 2014). "Huye el alcalde de Iguala luego de pedir licencia" (in Spanish). La Prensa. Organización Editorial Mexicana. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- Johnson, Tim (November 4, 2014). "New hope for break in case of missing students as ex-mayor captured". The Tribune. The McClatchy Company. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- Flores Contreras, Ezequiel (October 1, 2014). "Alcalde de Iguala está prófugo; emiten orden de presentación en su contra". Proseco (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- Christiansen, Ana (October 10, 2014). "More bodies found in case of 43 missing Mexican students". PBS NewsHour. Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- Mosso, Rubén (October 9, 2014). "Juez otorga suspensión que impide captura de Abarca" (in Spanish). Milenio. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- Daly, Michael (October 29, 2014). "Mexico's First Lady of Murder Is on the Lam". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "5 preguntas básicas sobre las licencias de los funcionarios" (in Spanish). CNNMéxico. Turner Broadcasting System. October 31, 2014. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- "Mexico students: Guerreros Unidos gang leader 'arrested'". BBC News. October 18, 2014. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Mexico issues arrest warrants on sixth anniversary of disappearance of 43 college students". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- "El negro historial de Abarca Velázquez". SinEmbargo OPINIÓN. October 6, 2014. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- "Borderland Beat: Guerreros Unidos: Narco Banners appear demanding release of 22 municipal police..." Borderlandbeat.com. October 2014. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- "Governor says human remains found in Mexico mass grave had been burned". The Guardian. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- "Mexico missing students: Nationwide protests held". BBC News. October 8, 2014. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- "La vigilancia en Iguala, a manos de la Gendarmería". La Jornada. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- JACOBO G. GARCÍA (October 5, 2014). "Matanza en México: 'Los quemaron vivos en la fosa' – EL MUNDO". ELMUNDO. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- "Anatomy of a Mexican Student Massacre". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- "Mexico faces crucial test in the investigation of the deaths and enforced disappearances of students in Guerrero". OHCHR. October 10, 2014. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- "Protesters burn Mexican city's government offices over suspected murder of students". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- "Normalistas y maestros queman el Palacio de Gobierno en Chilpancingo". La Prensa. October 13, 2014. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- "Desahogaron su frustración por la desaparición de los 43 normalistas". Diario de Guerrero. October 14, 2014. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- "Hallan Otras 4 Fosas en Iguala; Cuerpas de las Primeras No Son de Normalistas: PGR". Proceso. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- Tim Johnson (October 22, 2014). "Protesters burn city hall in Mexico town where 43 students vanished". News Observer. Mexico. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- "Abarca ordenó atacar a normalistas: PGR" (in Spanish). Milenio. October 21, 2014. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- "Abarca y esposa, autores intelectuales de la desaparición de normalistas: PGR". Proceso (in Spanish). October 22, 2014. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- Kleinfeld, Rachel; Barham, Elena (2018). "Complicit States and the Governing Strategy of Privilege Violence: When Weakness is Not the Problem". Annual Review of Political Science. 21: 215–238. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-015628.

- "Mass protests in Mexico over Iguala Massacre". World Socialist Web Site. October 24, 2014. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- Kahn, Carrie (October 31, 2014). "With Mexican Students Missing, A Festive Holiday Turns Somber : Parallels". NPR. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Ángel Aguirre se va" (in Spanish). Milenio. October 23, 2014. Archived from the original on November 1, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- Romo, Rafael (October 24, 2014). "Mexican governor steps aside after student kidnappings". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- Archibold, Randal C. (October 23, 2014). "In Mexico, an Embattled Governor Resigns". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- "Rogelio Ortega Martinez Named as New Governor of Guerrero, Mexico – HispanicallySpeakingNews.com". HS-News.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014.

- "New mass grave found in hunt for missing Mexican students". Al Jazeera. October 28, 2014. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- Morales, Alberto (October 28, 2014). "Buscan a desaparecidos en un paraje de Cocula". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- "A unas horas de asumir el cargo, Mazón pide licencia a alcaldía de Iguala" (in Spanish). Animal Político. Elephant Publishing, LLC. October 29, 2014. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- "Con Cabildo de Iguala no puedo trabajar: Luis Mazón" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Milenio. October 30, 2014. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- Morelos, Rubicela (October 16, 2014). "Aguirre cesa a su titular de Salud; lo liga al edil Abarca". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- Reyes, Laura (October 30, 2014). "Luis Mazón rinde protesta como alcalde de Iguala... y luego pide licencia" (in Spanish). CNNMéxico. Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- "El Congreso de Guerrero elige a Silviano Mendiola como alcalde de Iguala" (in Spanish). CNNMéxico. Turner Broadcasting System. November 11, 2014. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- "Mexicans Protest Over Attorney General Remarks on Ayotzinapa Case (11/8/2014)". La Cartita. December 17, 2017. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- "Mexico: protests at admission that 43 missing students were massacred". The Guardian. November 9, 2014. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- "Mexico missing students: Capital sees mass protests". BBC News. November 21, 2014. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- Flores Contreras, Ezequiel (November 24, 2014). "Dejan el miedo y salen a buscar a sus desaparecidos en Iguala; hallan 7 fosas y restos óseos". Proceso (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 24, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- Navarro, Israel (November 23, 2014). "Padres de otros desaparecidos hallan 10 fosas más en Iguala" (in Spanish). Milenio. Archived from the original on November 27, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- Michel, Víctor Hugo (November 25, 2014). "Llegan peritos de PGR a Iguala para analizar restos de fosas" (in Spanish). Milenio. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- "UPOEG integrará comités de búsqueda" (in Spanish). Periódico AM. November 25, 2014. Archived from the original on November 27, 2014. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- Ocampo Arista, Sergio (November 25, 2014). "Asegura la Upoeg que halló en 2 años 500 cuerpos de ejecutados" (in Spanish). La Jornada. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- "La ONU-DH México anuncia el nombramiento de Javier Hernández Valencia como Representante de la Alta Comisionada en México". ONU-DH Mexico. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- "México: ONU-DH visita a familiares de normalistas desaparecidos en Ayotzinapa". Noticias ONU (in Spanish). December 3, 2014. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- "Doble injusticia – Informe sobre violaciones de derechos humanos en la investigación del caso Ayotzinapa | ONU-DH". hchr.org.mx. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Mexico missing: Protesters try to enter army base". BBC News. January 13, 2015. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2015.