2018 Atlantic hurricane season

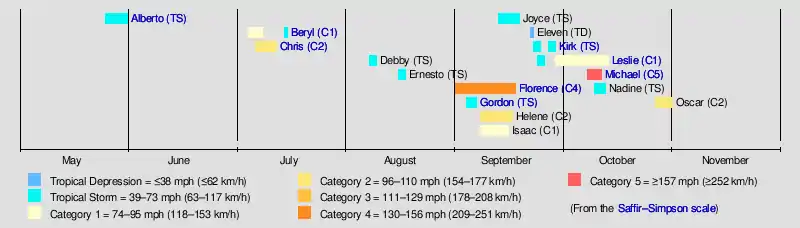

The 2018 Atlantic hurricane season was the third in a consecutive series of above-average and damaging Atlantic hurricane seasons, featuring 15 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes,[nb 1] which caused a total of over $50 billion (2018 USD) in damages and at least 172 deaths.[nb 2] More than 98% of the total damage was caused by two hurricanes (Florence and Michael). The season officially began on June 1, 2018, and ended on November 30, 2018. These dates historically describe the period in each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin and are adopted by convention.[2] However, subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the formation of Tropical Storm Alberto on May 25, making this the fourth consecutive year in which a storm developed before the official start of the season.[3] The season concluded with Oscar transitioning into an extratropical cyclone on October 31, almost a month before the official end.

| 2018 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 25, 2018 |

| Last system dissipated | October 31, 2018 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Michael |

| • Maximum winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 919 mbar (hPa; 27.14 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 16 |

| Total storms | 15 |

| Hurricanes | 8 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 172 total |

| Total damage | > $50.526 billion (2018 USD) |

| Related articles | |

| |

Although several tropical cyclones impacted land, only a few left extensive damage. In mid-September, Hurricane Florence produced disastrous flooding in North Carolina and South Carolina, with damage totaling about $24 billion. The storm also caused 54 deaths. About a month later, Hurricane Michael, the first tropical cyclone to strike the United States as a Category 5 hurricane since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, left extensive damage in Florida, Georgia, and Alabama. Michael caused approximately $25 billion in damage and at least 64 deaths. Since Michael reached Category 5 status, 2018 became the third consecutive season to feature at least one Category 5 hurricane. Hurricane Leslie resulted in the first tropical storm warning being issued for the Madeira region of Portugal. Leslie and its remnants left hundreds of thousands of power outages and downed at least 1,000 trees in the Portuguese mainland, while heavy rains generated by the remains of the cyclone caused 15 deaths in France. The storm left approximately $500 million in damage and 16 fatalities.

Most forecasting groups called for a below-average season due to cooler than normal sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic and the anticipated development of an El Niño. However, the anticipated El Niño failed to develop in time to suppress activity, and activity exceeded most predictions.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| Average (1981–2010) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | [4] | |

| Record high activity | 30 | 15 | 7† | [5] | |

| Record low activity | 4 | 2† | 0† | [5] | |

| TSR | December 7, 2017 | 15 | 7 | 3 | [6] |

| CSU | April 5, 2018 | 14 | 7 | 3 | [7] |

| TSR | April 5, 2018 | 12 | 6 | 2 | [8] |

| NCSU | April 16, 2018 | 14–18 | 7–11 | 3–5 | [9] |

| TWC | April 19, 2018 | 13 | 7 | 2 | [10] |

| TWC | May 17, 2018 | 12 | 5 | 2 | [10] |

| NOAA | May 24, 2018 | 10–16 | 5–9 | 1–4 | [11] |

| UKMO | May 25, 2018 | 11* | 6* | N/A | [12] |

| TSR | May 30, 2018 | 9 | 4 | 1 | [13] |

| CSU | May 31, 2018 | 14 | 6 | 2 | [14] |

| CSU | July 2, 2018 | 11 | 4 | 1 | [15] |

| TSR | July 5, 2018 | 9 | 4 | 1 | [16] |

| CSU | August 2, 2018 | 12 | 5 | 1 | [17] |

| TSR | August 6, 2018 | 11 | 5 | 1 | [18] |

| NOAA | August 9, 2018 | 9–13 | 4–7 | 0–2 | [19] |

| Actual activity | 15 | 8 | 2 | ||

| * June–November only † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

Ahead of and during the season, several national meteorological services and scientific agencies forecast how many named storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes will form during a season or how many tropical cyclones will affect a particular country. These agencies include the Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) Consortium of University College London, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Colorado State University (CSU). The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year. Some of these forecasts also take into consideration what happened in previous seasons and an ongoing La Niña event that had recently formed in November 2017.[20] On average, an Atlantic hurricane season between 1981 and 2010 contained twelve tropical storms, six hurricanes, and three major hurricanes, with an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index of between 66 and 103 units.[4] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of a hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed; therefore, long-lived storms and particularly strong systems result in high levels of ACE. The measure is calculated at full advisories for cyclones at tropical storm strength—storms with winds in excess of 39 mph (63 km/h).[21]

Pre-season outlooks

The first forecast for the year was released by TSR on December 7, 2017, which predicted a slightly above-average season for 2018, with a total of 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[6] On April 5, 2018, CSU released its forecast, predicting a slightly above-average season with 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[7] TSR released its second forecast on the same day, predicting a slightly-below average hurricane season, with 12 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes, the reduction in both the number and size of storms compared to its first forecast being due to recent anomalous cooling in the far northern and tropical Atlantic.[8] Several days later, on April 16, North Carolina State University released its predictions, forecasting an above-average season, with 14–18 named storms, 7–11 hurricanes, and 3–5 major hurricanes.[9] On April 19, The Weather Company (TWC) released its first forecasts, predicting 2018 to be a near-average season, with a total of 13 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes.[10]

TWC revised their forecast slightly on May 17, instead projecting 12 named storms, 5 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes in their May 17 outlook.[10] On May 24, NOAA released their first forecasts, calling for a near to above average season in 2018.[11] On May 25, the UK Met Office released their prediction, predicting 11 tropical storms, 6 hurricanes, and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) value of approximately 105 units.[12] In contrast, on May 30, TSR released their updated prediction, significantly reducing their numbers to 9 named storms, 4 hurricanes and 1 major hurricane, citing a sea surface temperature setup analogous of those observed during the cool phase of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation.[13] On May 31, one day before the season officially began, CSU updated their forecast to include Tropical Storm Alberto, also decreasing their numbers due to anomalous cooling in the tropical and far northern Atlantic.[14]

Mid-season outlooks

On July 2, CSU updated their forecast once more, lowering their numbers again to 11 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 1 major hurricane, citing the continued cooling in the Atlantic and an increasing chance of El Niño forming later in the year.[15] TSR released their fourth forecast on July 5, retaining the same numbers as their previous forecast.[16] On August 2, CSU updated their forecast again, increasing their numbers to 12 named storms, 5 hurricanes, and 1 major hurricane, citing the increasing chance of a weak El Niño forming later in the year.[17] Four days later, TSR issued their final forecast for the season, slightly increasing their numbers to 11 named storms, 5 hurricanes and only one major hurricane, with the reason of having two unexpected hurricanes forming by the beginning of July.[18] On August 9, 2018, NOAA revised its predictions, forecasting a below-average season with 9–13 named storms, 4–7 hurricanes, and 0–2 major hurricanes for all of the 2018 season.[19]

Seasonal summary

The 2018 Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1.[22] The season produced sixteen tropical depressions, all but one of which further intensified into tropical storms. Eight of those strengthened into hurricanes, while two of the six hurricanes further strengthened into major hurricanes. A record seven storms received the designation of subtropical cyclone at some point in their duration.[23] Above normal activity occurred due to anomalously warm sea surface temperatures, a stronger west-African monsoon, and the inability for the El Nino to develop during the season.[22] The Atlantic tropical cyclones of 2018 collectively caused 172 fatalities and just over $50.2 billion in damage.[24] The Atlantic hurricane season officially ended on November 30, 2018.[22]

Tropical cyclogenesis began with the formation of Tropical Storm Alberto on May 25, marking the fourth consecutive year that activity began early.[22] However, no storms developed in the month of June. July saw the formation of Beryl and Chris, both of which intensified into hurricanes. August also featured two named storms, Debby and Ernesto, though neither strengthened further than tropical storm status. On August 31, the depression that would later become Hurricane Florence developed. September featured the most activity, with Florence, Gordon, Helene, Isaac, Joyce, Tropical Depression Eleven, Kirk, and Leslie also forming or existing in the month.[23] Florence, Helene, Isaac, and Joyce existed simultaneously for a few days in September, becoming the first time since 2008 that four named storms were active at the same time.[22] The season also became the second consecutive year with three hurricanes simultaneously active.[25]

| Rank | Cost | Season |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥ $294.703 billion | 2017 |

| 2 | $172.297 billion | 2005 |

| 3 | ≥ $80.727 billion | 2021 |

| 4 | $72.341 billion | 2012 |

| 5 | $70.19 billion | 2022 |

| 6 | $61.148 billion | 2004 |

| 7 | ≥ $51.146 billion | 2020 |

| 8 | ≥ $50.126 billion | 2018 |

| 9 | ≥ $48.855 billion | 2008 |

| 10 | $27.302 billion | 1992 |

Activity continued in October, with Michael forming on October 7 and strengthening into a major hurricane over the Gulf of Mexico, before making landfall in the Florida Panhandle at peak intensity. Michael, which peaked as a Category 5 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 919 mbar (27.1 inHg), was the most intense tropical cyclone of the season and one of only four storms to make landfall in the United States mainland as a Category 5,[23][26] the others being the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, Hurricane Camille in 1969, and Hurricane Andrew in 1992.[27] After 15 consecutive days as a tropical cyclone, Leslie transitioned into a powerful extratropical cyclone on October 13 while situated approximately 120 mi (195 km) west of the Iberian Peninsula, before making landfall soon afterward. A two-week period of inactivity ensued as the season began to wind down. Oscar, forming as a subtropical storm on October 26, intensified into a hurricane the next day, making it the eighth hurricane of the season. Oscar's extratropical transition ended the season's activity on October 31.[23] No systems formed in the month of November for the first time since 2014.[22] The seasonal activity was reflected with an Accumulated Cyclone Energy index value of 133 units.[28]

Systems

Tropical Storm Alberto

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 25 – May 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 990 mbar (hPa) |

A broad area of low pressure formed over the northwestern Caribbean Sea on May 20 due to the diffluence of a trough. Dry air and wind shear initially prevented development as the low moved over the Yucatán Peninsula. However, after the low re-emerged into the Caribbean on May 25, a well-defined circulation developed and the system became a subtropical depression about 80 mi (130 km) east-southeast of Chetumal, Quintana Roo, around 12:00 UTC. After remaining nearly stationary for the next day, the subtropical depression moved northward and continued strengthening, becoming Subtropical Storm Alberto as it crossed into the Gulf of Mexico late on May 26. After convection migrated closer to the circulation and the Alberto's wind field decreased in size, it transitioned into a tropical storm around 00:00 UTC on May 28. Around that time, Alberto peaked with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 990 mbar (29 inHg). Around 21:00 UTC, Alberto made landfall near Laguna Beach, Florida, with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). The cyclone weakened to a tropical depression shortly after landfall. Possibly due to the brown ocean effect, Alberto persisted as a tropical cyclone over land until transitioning into a remnant low over northern Michigan on May 31. A frontal system subsequently absorbed the remnant low over Ontario on June 1.[29]

Alberto and its precursor caused flooding in the Yucatán Peninsula, particularly in Mérida.[30] Flooding also occurred in Cuba, where the cyclone dropped 14.41 in (366 mm) of rainfall in Heriberto Duquezne, Villa Clara.[29] The storm damaged 5,218 homes and 23,680 acres (9,580 ha) of crops throughout the country.[31][32] Alberto caused 10 deaths in Cuba, all due to drowning. In Florida, sustained winds reached 51 mph (82 km/h) and gusts topped out at 59 mph (95 km/h), both recorded at the St. George Island Bridge. The winds knocked down dozens of trees, some of which fell onto roads, power lines,[29] and a few homes. Storm surge entered five buildings and a restaurant in the Florida Panhandle.[33] Farther inland, Alberto caused flooding in several states. Particularly hard hit was western North Carolina, where flooding and mudslides led to the closure of more than 40 roads, including parts of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Approximately 2,000 people fled their homes in McDowell County due to the threat of failure of the dam at Lake Tahoma. Alberto caused eight deaths and about $125 million in damage in the United States.[29]

Hurricane Beryl

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 4 – July 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 991 mbar (hPa) |

On July 1, a tropical wave and accompanying low-pressure area exited the west coast of Africa. While moving west-southwestward over the next few days, the system organized into a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on July 4 about 1,495 mi (2,405 km) west-southwest of the Cape Verde Islands. About 12 hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Beryl. Despite relatively cool sea surface temperatures, Beryl continued to strengthen, becoming a Category 1 hurricane by 06:00 UTC on July 6 as a pinhole eye became evident.[34] Beryl became the second earliest hurricane on record in the Main Development Region (south of 20°N and between 60° and 20°W), behind only a storm in 1933.[35] Simultaneously, the cyclone peaked with 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 991 mbar (29.3 inHg). Thereafter, increasing wind shear caused it to weaken back to a tropical storm by 12:00 UTC on July 7. A reconnaissance aircraft flight found that Beryl had degenerated into an open trough about 24 hours later. The remnants were monitored for several days. After conditions became more favorable, Beryl regenerated into a subtropical storm near Bermuda at 12:00 UTC on July 14. The rejuvenated storm soon began to lose convection due to dry air intrusion and degenerated into a remnant low once again by 00:00 UTC on July 16. An extratropical storm over Newfoundland absorbed the low on the following day.[34]

In Guadeloupe, four observation sites recorded tropical storm-force winds, downing trees and power lines. Rainfall on the island peaked at 7.8 in (200 mm) in Saint-Claude,[34] causing minor localized flooding due to runoff.[36] Gusty winds in Puerto Rico left approximately 47,000 people without power.[34] Flash flooding closed several road closures and downed several trees. In the Dominican Republic, heavy rainfall led to flooding that displaced more than 8,000 people and isolated 19 communities. Overall, the flooding damaged 1,586 homes and destroyed 2 others. Roughly 59,000 electrical customers lost power.[37] Total damage was estimated to be in the millions.[38]

Hurricane Chris

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 6 – July 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 969 mbar (hPa) |

A frontal system moved offshore the coast of the northeastern United States on July 2. The frontal system dissipated a few days later, but the remaining shower and thunderstorm activity developed into a non-tropical low by July 3. After further organization, a tropical depression formed around 12:00 UTC on July 6 about 345 mi (555 km) south-southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.[39] The depression's elongated circulation and the presence of dry air initially prevented intensification.[39][40] Nevertheless, at 06:00 UTC on July 8, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Chris. Pulled slowly southeastward by a passing cold front, Chris intensified little throughout the rest of the day due to upwelling. However, on July 10, a developing trough over the northeastern United States accelerated Chris eastward into warmer waters, allowing for the formation of an inner core. With a well-defined eye and impressive appearance on satellite imagery, Chris strengthened into a hurricane at 12:00 UTC that day. Chris proceeded to rapidly intensify and peaked as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) early on July 11,[39] with the convective ring in its core transforming into a full eyewall.[41] However, movement into cooler waters and the effects of a nearby mid-latitude trough caused Chris to begin to undergo extratropical transition. At 12:00 UTC on July 12, Chris became an extratropical cyclone well southeast of Newfoundland. The low continued northeastward over the Atlantic for the next few days, before weakening and finally dissipating south of Iceland on July 17.[39]

While offshore, Chris brought large swells to the East Coast of the United States, sparking hundreds of water rescues, especially along the coasts of North Carolina, New Jersey, and Maryland. On July 7, a man drowned in rough seas attributed to the storm at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina.[39] A vacation home in Rodanthe was declared uninhabitable after swells generated by Chris eroded away the base of the building.[42][39] As an extratropical cyclone, the system brought locally heavy rain and gusty winds to Newfoundland and Labrador. Rainfall accumulations peaked at 3.0 in (76 mm) in Gander, while gusts reached 60 mph (96 km/h) in Ferryland.[43] Rainfall accumulations were highest on Sable Island, at 4.39 in (111.6 mm).[44]

Tropical Storm Debby

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 7 – August 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 998 mbar (hPa) |

On August 4, the NHC began monitoring a non-tropical low over the northern Atlantic Ocean for tropical or subtropical development.[45] Initially, convection remained very limited, with the system consisting mostly of a convection-less swirl interacting with an upper-level low. However, as the system moved southwestward into a more favorable environment, it gradually began to acquire subtropical characteristics. A large band of convection with tropical storm-force winds developed far from the center of the strengthening circulation, leading to the formation of Subtropical Storm Debby at 06:00 UTC on August 7. Moving northward along the western side of a mid-level ridge, deep convection increased near the center of the cyclone, and Debby transitioned to a tropical storm at 00:00 UTC on August 8. Throughout the day, despite moving over marginal sea surface temperatures, Debby strengthened while turning north-northeastward to northeastward. The storm reached its peak intensity at 00:00 UTC on August 9 with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h). Although Debby's passage over a warm Gulf Stream eddy allowed it to maintain its intensity for a short time, the entrainment of dry air into its circulation and passage over cooler waters caused its deep convection to dissipate. Debby degenerated into a remnant low at 18:00 UTC on August 9 about 540 mi (870 km) east-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The system then transitioned to an extratropical cyclone early on August 10 before being absorbed by a larger extratropical cyclone later that day.[46]

Tropical Storm Ernesto

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 15 – August 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) |

A complex non-tropical low pressure system formed over the northern Atlantic on August 12. As the low drifted southeastward and slowly weakened, a new low formed to the east of the system on August 14. The new low quickly acquired subtropical characteristics, and by 06:00 UTC on August 15, the low had organized sufficiently to be classified as a subtropical depression while situated about 740 mi (1,190 km) southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. Turning northeastward along the southern periphery of the mid-latitude westerlies, the subtropical depression intensified into Subtropical Storm Ernesto about six hours later. After Ernesto became a warm core system, with sufficient convective organization and anticyclonic outflow, the cyclone transitioned into a fully tropical storm late on August 16.[47] By the following day, Ernesto began accelerating northeastward due to the influence of the mid-latitude westerlies.[48] Around 18:00 UTC, the cyclone peaked with maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,003 mbar (29.6 inHg). By six hours later, Ernesto transitioned into an extratropical low about 805 mi (1,295 km) north-northeast of the Azores. The low merged with a frontal system and continued east-northeastward until dissipating over the British Isles on August 19.[47] Heavy rains fell in portions of the United Kingdom on that day.[49]

Hurricane Florence

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 31 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min) 937 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave and a broad low-pressure area exited the west coast of Africa on August 30. The southern portion of the wave moved westward for a few weeks and developed into Tropical Depression Nineteen-E in the Eastern Pacific Ocean on September 19, while the remaining portions of the wave and the low formed into a tropical depression about 105 mi (170 km) southeast of the island of Santiago in the Cabo Verde Islands late on August 31. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Florence early the next day. Florence moved west-northwestward at an average speed of 17 mph (27 km/h) due to a large ridge associated with the Bermuda-Azores High. Marginally favorable conditions allowed for only gradual intensification, with the cyclone becoming a hurricane on September 4. However, Florence then underwent rapid intensification, reaching Category 4 status by late on the next day,[50] farther northeast than any previous Category 4 hurricane in the Atlantic during the satellite era.[51] A sharp increase in wind shear then led to rapid weakening, with Florence falling to tropical storm intensity by early on September 7. A building mid-level ridge halted Florence's northward movement, leading to a westward turn.[50]

Wind shear decreased again and the storm crossed into warmer ocean temperatures, allowing Florence to re-strengthen into a hurricane on September 9. On the next day, Florence underwent a second bout of rapid intensification, reaching Category 4 intensity again late on September 10. After additional strengthening, the cyclone reached its peak intensity around 18:00 UTC on September 11, with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 937 mbar (27.7 inHg). The system steadily weakened thereafter due to upwelling and eyewall replacement cycles, with the storm falling below major hurricane intensity on September 13 as it neared the Carolinas. Florence then slowed significantly due to collapsed steering currents and made landfall near Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina, as a Category 1 with winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) around 11:15 UTC on September 14. Jogging to the west-southwest, the cyclone remained near the coast and weakened to a tropical storm over eastern South Carolina early on September 15. Florence weakened to a tropical depression over the western part of the state late on the next day before turning northward. The system then became extratropical over West Virginia. The extratropical system tracked northeastward due to an approaching frontal system prior to dissipating over Massachusetts on September 18.[50]

Florence brought catastrophic flooding to North Carolina and South Carolina. In the former, the storm dropped a maximum total of 35.93 in (913 mm) of precipitation near Elizabethtown, making Florence the rainiest tropical cyclone on record in North Carolina. Floodwaters entered 74,563 structures and inundated nearly every major highway in eastern North Carolina for several days. Several cities became completely isolated, including Wilmington. A total of 5,214 people required rescue during the flood. Significant losses to crops and livestock also occurred, with the deaths of 5,500 hogs and 3.5 million poultry. Approximately one million people lost electricity at the height of the storm. Damage in North Carolina alone totaled approximately $22 billion. In South Carolina, Florence produced a maximum total of 23.63 in (600 mm) of precipitation in Loris, also becoming the wettest tropical cyclone in the history of that state. Though flooding was not as severe as in North Carolina, the storm still inflicted a multi-billion dollar disaster in South Carolina, with damage totaling about $2 billion. Approximately 11,386 homes throughout the state experienced moderate or major damage. Interstate 95 remained closed for about a week due to inundation. In Virginia, the storm caused generally minor flooding and spawned 11 tornadoes. A tornado in Chesterfield County overturned cars, downed a number of power lines, deroofed several buildings, and destroyed a warehouse, killing a man inside.[50] Overall, Florence killed 54 people and caused just over $24 billion in damages.[50][52][53]

Tropical Storm Gordon

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 3 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 996 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave departed the west coast of Africa on August 26 and moved quickly across the tropical Atlantic with little convective activity. On August 30, an increase in convection occurred as the wave approached the Caribbean Sea. Gradual organization occurred as the system moved northwestward toward the Bahamas. At 06:00 UTC on September 3, a tropical depression formed about 90 mi (140 km) southeast of Key Largo, Florida, and strengthened into Tropical Storm Gordon just three hours later. Moving west-northwestward to northwestward around a strong subtropical ridge, Gordon continued to strengthen and reached winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) as it made landfall near Tavernier, Florida, at 11:15 UTC. After making a second landfall near Flamingo at 13:15 UTC, Gordon emerged into the Gulf of Mexico. An eye-like feature briefly appeared late on September 3 as the small tropical cyclone continued to strengthen. At 18:00 UTC on September 4, Gordon peaked with maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h), making landfall at that intensity at 03:15 UTC the following day near the Alabama-Mississippi border. The tropical storm quickly weakened to a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC, degenerating into a remnant low at 18:00 UTC on September 6 over Arkansas. The remnant low degenerated into a trough early on September 8 before merging with a developing extratropical low later that day.[54]

Several locations in South Florida observed tropical-storm-force wind gusts. Over 8,000 people lost power in Broward and Miami-Dade counties.[54] One death occurred in Miami on Interstate 95 when a truck driver lost control of his vehicle, crashed into a wall, and was ejected from the truck.[55] Rainfall reaching 6.98 in (177 mm) in Homestead caused some street flooding in the Miami area.[54][56] Along the Gulf Coast, especially the Florida Panhandle, Alabama, and Mississippi, winds and storm surge caused damage to some piers, homes, and buildings. About 27,000 people lost electricity, with most in Alabama and the Florida Panhandle. A young girl died in Pensacola after a tree fell on her mobile home. Tornadoes and flash floods from the remnants of Gordon caused some damage farther inland, especially in Kentucky and Missouri. The storm caused two deaths in the former and one in the latter. Gordon resulted in approximately $200 million in damage throughout the United States.[54]

Hurricane Helene

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 967 mbar (hPa) |

In early September, a vigorous tropical wave moving across west Africa produced a large mass of convection. While still inland, a surface low pressure area formed in association with the wave on September 6.[57] Heavy rainfall from the precursor tropical wave in Guinea triggered flooding, which claimed three lives in Doko.[58] The system moved offshore early on September 7 and developed into a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC near Banjul, The Gambia. Steered westward due to a subtropical ridge to the north, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Helene early on September 8.[57] In the Cabo Verde Islands, winds downed trees and a telecommunications antenna in the city of São Filipe. The storm also caused minor damage to buildings, vehicles, and roads.[59] Improvement of banding features and the development of an inner core indicated further strengthening; Helene became a hurricane around 18:00 UTC the following day.[57] Helene was the second easternmost hurricane to form in the main development region (MDR) during the satellite era, behind only Fred in 2015.[60] Helene then curved west-northwestward around the edge of the subtropical ridge and intensified further, becoming a Category 2 hurricane around 12:00 UTC on September 10. Approximately 24 hours later, the cyclone peaked with winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 967 mbar (28.6 inHg).[57]

Colder water temperatures and drier air caused Helene to weaken to a tropical storm on September 13. The flow between a trough over the central Atlantic and the subtropical ridge then drew Helene in a northward motion.[57] On September 13 and September 14, the cyclone underwent a Fujiwhara interaction with the smaller Tropical Storm Joyce to the west.[61] Afterward, Helene accelerated northeastward and passed over the Azores late on September 15. The storm likely produced tropical storm-force winds over the western Azores. The next day, Helene transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while speeding toward the British Isles,[57] becoming the first named storm of the European windstorm season.[62] On September 18, the extratropical low associated with Helene merged with another extratropical system.[57] The remnants continued onwards to impact Ireland and the United Kingdom, prompting warnings for wind gusts up 65 mph (105 km/h) for southern and western areas of the United Kingdom.[63] However, Helene weakened considerably while approaching the British Isles, resulting in the cancellation of all weather warnings on September 18. The extratropical storm produced rainfall across the British Isles and wind gusts reaching 50 mph (80 km/h) in Wales.[64]

Hurricane Isaac

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) |

On September 2, a tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa. The system gradually organized over the next several days. After a burst of deep convection on September 6 and then the development of a well-defined center shortly after, a tropical depression formed about 690 mi (1,110 km) west of the Cabo Verde Islands around 12:00 UTC on September 7. Weak steering currents caused the depression to initially move slowly, while moderate wind shear temporarily prevented the system from strengthening. At 12:00 UTC on September 8, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Isaac. Thereafter, the cyclone began moving westward between 12 and 17 mph (19 and 27 km/h) after a subtropical ridge situated north of the storm strengthened. With warm ocean temperatures, abundant moisture, and low wind shear, Isaac intensified into a hurricane at 00:00 UTC on September 10. Simultaneously, the cyclone peaked with sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 995 mbar (29.4 inHg).[65]

Later on September 10, dry air entered the storm's small circulation, suppressing convection and preventing any further intensification. Increasing wind shear generated by an upper-level trough to the north caused Isaac to weaken, with the cyclone falling to tropical storm intensity early on September 11. Between September 12 and September 13, the system's surface circulation became exposed from the convection. Around 12:00 UTC on September 13, Isaac passed between Martinique and Dominica, with the high terrain on Martinique nearly causing the storm to dissipate. On Dominica, the cyclone caused minor flooding and mudslides.[65] Wind gusts peaked at 53 mph (86 km/h) on Guadeloupe, causing hundreds of power outages.[66] Locally heavy rainfall on Saint Lucia caused flooding in Anse La Raye and Castries, while winds downed trees in Barre de L'isle. Although convection briefly re-developed, persistent wind shear caused Isaac to weaken to a tropical depression early on September 15 and then degenerate into a tropical wave about halfway between the Dominican Republic and Venezuela shortly thereafter.[65]

Tropical Storm Joyce

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 12 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) |

A cold front moved offshore New England and Atlantic Canada around September 7. A non-tropical low pressure area developed along the front three days later and reached gale-force intensity by early on September 12. After a curved band of convection formed later that day, the low became Subtropical Storm Joyce by 12:00 UTC while centered roughly 615 mi (990 km) west-southwest of Flores Island in the Azores.[67] From September 13-September 14, Joyce interacted with the larger Hurricane Helene, due to the Fujiwhara effect, with Joyce being steered counter-clockwise around Helene.[61] At 00:00 UTC on September 14, Joyce transitioned into a tropical storm. Later that day, Joyce began turning eastward and reached its peak intensity with sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h). Afterward, Joyce began to weaken due to the increasing wind shear. At 12:00 UTC on September 16, Joyce weakened into a tropical depression. At 00:00 UTC on September 19, Joyce degenerated into a remnant low, which continued an eastward motion for another couple of days, before dissipating late on September 21.[67]

Tropical Depression Eleven

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 21 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa on September 14, with signs of rotation. As the wave traversed the tropical Atlantic, rotation slightly weakened. After a few days moving westward, convection and organization gradually improved.[68] On September 18, a large area of disturbed weather in association with a tropical wave developed far to the east-southeast of the Lesser Antilles.[69] The system initially lacked a surface circulation, and though a weak low formed on September 20,[68] strong upper-level winds and dry air were expected to limit further development.[70] Deep convection, despite being displaced east of the center, became persistent throughout the day, leading to the formation of a tropical depression by 18:00 UTC on September 21. However, the depression failed to strengthen further within an increasingly hostile environment, eventually degenerating into an elongated trough on the following day approximately 345 mi (555 km) east of the Lesser Antilles.[68]

Tropical Storm Kirk

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 22 – September 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 998 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on September 22. The wave moved swiftly westward and organized into a tropical depression about 520 mi (835 km) south-southeast of the Cabo Verde Islands early on September 22. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Kirk about six hours later, becoming a named storm at 8.1°N, the lowest latitude for a system of tropical storm strength or higher in the north Atlantic since an a hurricane in 1902. Little change in strength occurred as Kirk accelerated across the tropical Atlantic, possibly owing to its high forward speed, and the cyclone degenerated into an open tropical wave at 12:00 UTC on September 23. The remnant trough continued westward and reorganized, becoming a tropical storm once again early on September 26. Kirk peaked with sustained winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) later that day. Strong wind shear weakened the storm slightly over the next day as it approached the Lesser Antilles, and around 00:30 UTC on September 28, the storm made landfall on St. Lucia. Kirk continued to weaken while moving westward through the Caribbean, and the surface circulation became exposed to the west of the main convection. Early on September 29, Kirk degenerated into an open tropical wave over the eastern Caribbean.[71] Kirk's remnants drifted westward for the next couple of days, before being absorbed by a developing area of low pressure over the southwest Caribbean, which would later become Hurricane Michael.[26]

Tropical storm watches and warnings were issued for the Windward Islands at 09:00 UTC on September 26.[71] The storm caused the loss of roughly 80% of banana and plantain crops and also damaged school buildings,[72] while two buildings suffered complete destruction.[73] Approximately 2,000 chickens died at a poultry farm after their pens collapsed during the storm.[74] Damage in St. Lucia totaled approximately $444,000.[72] Rainfall amounts exceeding 10 in (250 mm) on Barbados caused extensive street flooding and power outages.[71] Two deaths occurred in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines after two fishermen ignored storm warnings and presumably drowned.[75]

Hurricane Leslie

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 23 – October 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 968 mbar (hPa) |

A non-tropical area of low pressure formed over the central Atlantic on September 22, quickly transitioning into Subtropical Storm Leslie by 12:00 UTC on the next day about 945 mi (1,520 km) southwest of Flores Islands in the Azores. After little change in strength over the two days, Leslie weakened to a subtropical depression early on September 25, before becoming post-tropical later that day. After merging with a frontal system, Leslie began a cyclonic loop to the west, intensifying during this time, and becoming a powerful extratropical cyclone with hurricane-force winds early on September 27. The remnants of Leslie then gradually weakened, as the storm began to lose its frontal structure. However, Leslie became a subtropical storm once again around 12:00 UTC on September 28. A day after regenerating, Leslie became fully tropical.[76]

Over the next several days, Leslie drifted south-southwestward between a high pressure area to the west and another to the northeast while gradually intensifying. At 06:00 UTC on October 3, Leslie strengthened into a hurricane and turned northward, but weakened back to a tropical storm later on the next day. Leslie then drifted northeastward on October 5 and October 6 without much change in intensity, before turning east-southeastward along the western periphery of a broad mid-tropospheric trough on October 7. After a period of weakening, Leslie began restrengthening late on October 8, reaching hurricane intensity for the second time on October 10 while executing a sharp turn to the east-northeast. The cyclone then accelerated due to the influence of the mid-latitude westerlies. Late on October 13, Leslie became extratropical roughly 120 mi (195 km) west-northwest of Lisbon, Portugal, before making landfall soon afterward. The extratropical low became ill-defined after emerging into the Bay of Biscay on the next day.[76]

On October 12, a tropical storm warning was issued for Madeira for the first time in the island's history, and Leslie became the first tropical cyclone to pass within 100 mi (160 km) of the archipelago since reliable record-keeping began in 1851. Prior to Leslie, Hurricane Vince in 2005 passed closer to the islands than any other tropical cyclone.[77] Madeira officials closed beaches and parks.[78] The threat of the storm caused eight airlines to cancel flights into Madeira. Leslie resulted in the cancellation of over 180 sports matches, more than half of them affecting the Madeira Football Association.[79] On the mainland of Portugal, the remnants of Leslie produced wind gusts of 109 mph (175 km/h),[76] leaving 324,000 homes without power and downing at least 1,000 trees in coastal areas.[80] One death occurred due to a falling tree.[76] Moisture from the remnants of Leslie and a semi-stationary cold front caused heavy rainfall and flash flooding over southern France.[81] The flooding left 15 deaths, all in the Aude department.[82] Overall, Leslie and its remnants inflicted more than $500 million in damage.[83]

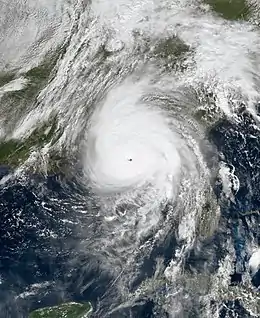

Hurricane Michael

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 7 – October 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min) 919 mbar (hPa) |

On October 1, a broad area of low pressure formed over the southwestern Caribbean Sea, absorbing the remnants of Tropical Storm Kirk by the next day. The low gradually organized, becoming a tropical depression early on October 7 about 150 mi (240 km) south of Cozumel. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Michael shortly thereafter. Michael quickly became a hurricane around midday on October 8 as a result of rapid intensification. The storm reached the Gulf of Mexico several hours later and continued to quickly strengthen over the next two days, becoming a major hurricane late on October 9. At 17:30 UTC on October 10, Michael made landfall near Panama City, Florida, at its peak intensity as a Category 5 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 919 mbar (27.1 inHg). Michael became the most intense storm of the season and also the third-strongest landfalling hurricane in the U.S. on record in terms of central pressure. The cyclone initially weakened quickly over land, falling to tropical storm intensity over Georgia early on October 11. By 00:00 UTC on October 12, Michael became extratropical over Virginia. After crossing through the Southeastern United States, Michael started restrengthening early on October 12 as a result of baroclinic forcing while transitioning into an extratropical cyclone. The extratropical low moved northeastward across the Atlantic, before curving southeastward and then southward while nearing the European mainland. The low dissipated just offshore Portugal on October 15.[26]

The combined effects of the precursor low to Michael and a disturbance over the Pacific Ocean caused significant flooding across Central America. Nearly 2,000 homes in Nicaragua suffered damage and 1,115 people evacuated. A total of 253 and 180 homes were damaged in El Salvador and Honduras, respectively.[84] More than 22,700 people were directly affected throughout the three countries.[85] The precursor of Michael caused roughly $10 million in damages in Central America and killed at least 15 people across the region: 8 in Honduras, 4 in Nicaragua, and 3 in El Salvador.[26][83] In Cuba, high winds from Michael resulted in more than 200,000 power outages and caused sporadic structural damage in Pinar del Río Province.[86][87] Heavy rains overflowed creeks and rivers, while floodwaters entered homes in La Coloma.[87] Catastrophic damage occurred in portions of the Florida Panhandle, particularly in and around Mexico Beach, Panama City, and Panama City Beach. Michael damaged more than 45,000 structures and destroyed over 1,500 others in Bay County alone. Major wind damage continued well inland, including about 1,000 structures experiencing substantial damage or destruction in Jackson County. In Georgia, 99% of homes in Seminole County suffered some degree of damage, while thousands of other homes as far north as Dougherty County reported damage. Extensive wind damage also occurred in southeastern Alabama. The remnants of Michael caused flooding in western North Carolina and Virginia, with a maximum precipitation total of 13.01 in (330 mm) near Black Mountain, North Carolina. In the United States, at least 59 people were killed across Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia, with most in the state of Florida. Michael caused at least $25 billion in property damage in the United States.[26]

Tropical Storm Nadine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 9 – October 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) |

Early on October 6, a tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa. The wave soon fractured as it moved into the tropical Atlantic, with the northern portion moving over cool waters and the southern portion continuing westward over warm waters. Convection associated with the southern portion increased and became more organized, and a well-defined circulation developed on October 7. The disturbance continued to organize over the next day as a well-defined surface low developed. At 06:00 UTC on October 9, while located southwest of Cape Verde, the disturbance organized into a tropical depression, and six hours later strengthened into Tropical Storm Nadine.[88] Upon its designation as a tropical storm at the longitude of 30°W, Nadine became the easternmost named storm to develop in the tropical Atlantic so late in the calendar year.[89] Located within a very favorable environment with low wind shear, warm sea surface temperatures, and abundant atmospheric moisture, the small tropical cyclone quickly intensified, reaching its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) around 06:00 UTC on October 10. At that time, a well-defined eye feature was evident in microwave imagery. However, an abrupt increase in westerly wind shear brought an end to the strengthening trend, and Nadine began to weaken later that day. Turning sharply west-northwestward, Nadine encountered hostile environmental conditions which resulted in the cyclone weakening to a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on October 12. The weakening cyclone degenerated into an open wave six hours later. The wave continued to move westward for the next several days, finally dissipating just east of the Lesser Antilles early on October 16.[88]

Hurricane Oscar

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 26 – October 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 966 mbar (hPa) |

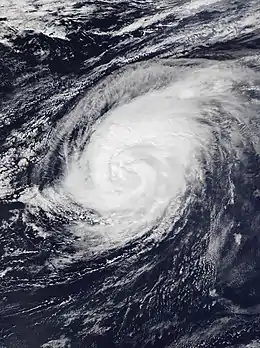

The interaction of a tropical wave and a mid- to upper-level trough resulted in the formation of a surface trough and a broad low-pressure area well northeast of the Leeward Islands on October 24. Gradual organization ensued as the low drifted northward, with the shower and thunderstorm activity becoming better defined. By 18:00 UTC on October 26, the circulation of the broad low had become sufficiently defined for it to be classified as Subtropical Storm Oscar while situated roughly 1,180 mi (1,900 km) east-northeast of the Leeward Islands. Oscar continued to strengthen as it accelerated westward around the northern side of a mid to upper-level low, transitioning into a tropical storm at 18:00 UTC on October 27. A small eye became evident on satellite imagery by late on October 28, and Oscar strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane at 18:00 UTC that day. Continued intensification followed, with Oscar peaking as a strong Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) early on October 30. Soon afterward, the cyclone accelerated northeastward over increasingly colder waters, while a cold front approached the system from the northwest. On October 31, Oscar underwent an extratropical transition, a process it completed by 18:00 UTC that day about 605 mi (975 km) south-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The remnant extratropical storm continued north-northeastward and then northeastward before being absorbed by another extratropical low and frontal system near the Faroe Islands late on November 4.[90]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2018.[22] This was the same list used in the 2012 season, with the exception of the name Sara, which replaced Sandy.[91]

|

|

Retirement

On March 20, 2019, at the 41st session of the RA IV hurricane committee, the World Meteorological Organization retired the names Florence and Michael from its rotating naming lists due to the number of deaths and amount of damage they caused, and they will not be used again for an Atlantic hurricane. They will be replaced with Francine and Milton, respectively, for the 2024 season.[92]

Season effects

This is a table of the tropical cyclones that formed in the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a tropical wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in USD. Potential tropical cyclones are not included in this table.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberto | May 25–31 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 990 | Yucatán Peninsula, Greater Antilles, Gulf Coast of the United States, Southeastern United States, Midwestern United States, Ontario | $125 million | 18 | [29] | ||

| Beryl | July 4–15 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 991 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, The Bahamas, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada | >$1 million | None | [38] | ||

| Chris | July 6–12 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 969 | Bermuda, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada, Iceland | Minimal | 1 | [39] | ||

| Debby | August 7–9 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 998 | None | None | None | |||

| Ernesto | August 15–17 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1003 | Western Europe | None | None | |||

| Florence | August 31 – September 17 | Category 4 hurricane | 150 (240) | 937 | West Africa, Cape Verde, Bermuda, Southeastern United States, Mid-Atlantic States, Atlantic Canada | $24.2 billion | 24 (30) | [50][52][53] | ||

| Gordon | September 3–6 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 996 | Greater Antilles, The Bahamas, Gulf Coast of the United States, Eastern United States, Ontario | $200 million | 3 (1) | [54] | ||

| Helene | September 7–16 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 967 | West Africa, Cape Verde, Azores, Western Europe | Unknown | 3 | [58] | ||

| Isaac | September 7–15 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 995 | West Africa, Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles | Minimal | None | |||

| Joyce | September 12–18 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 995 | None | None | None | |||

| Eleven | September 21–22 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1007 | None | None | None | |||

| Kirk | September 22–28 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 998 | Lesser Antilles | $444,000 | 2 | [72][75] | ||

| Leslie | September 23 – October 13 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 968 | Azores, Bermuda, East Coast of the United States, Madeira, Iberian Peninsula, France | >$500 million | 2 (14) | [76][82][83] | ||

| Michael | October 7–11 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 919 | Central America, Yucatán Peninsula, Greater Antilles, Southeastern United States, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada, Iberian Peninsula | $25.5 billion | 31 (43) | [26][83] | ||

| Nadine | October 9–12 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 995 | None | None | None | |||

| Oscar | October 26–31 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 966 | Faroe Islands | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 16 systems | May 25 – October 31 | 160 (260) | 919 | >50.526 billion | 84 (88) | |||||

See also

- Weather of 2018

- Tropical cyclones in 2018

- Atlantic hurricane season

- 2018 Pacific hurricane season

- 2018 Pacific typhoon season

- 2018 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2017–18, 2018–19

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2017–18, 2018–19

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2017–18, 2018–19

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

Notes

- A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[1]

- All damage figures are in 2018 USD, unless otherwise noted

References

- Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 23, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- "Hurricane Season Information". Frequently Asked Questions About Hurricanes. Miami, Florida: NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. June 1, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- Forbes, Alex (June 1, 2022). "No Atlantic storms develop before hurricane season for first time in seven years". Macon, Georgia: WMAZ-TV. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. September 19, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 7, 2017). "Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2018" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "Slightly above-average 2018 Atlantic hurricane season predicted by CSU team". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. April 5, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 5, 2018). "Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2018" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Matthew Burns (April 16, 2018). "NCSU researchers predict active hurricane season". WRAL-TV. Raleigh, North Carolina. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Jonathan Belles (May 18, 2018). "Hurricane Outlook Calls for Another Active Hurricane Season". Atlanta, Georgia: The Weather Channel. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "NOAA predicts near or above-normal 2018 Atlantic hurricane season". KCBD. May 24, 2018. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "North Atlantic tropical storm seasonal forecast 2018". Met Office. May 25, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (May 30, 2018). "Pre-Season Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2018" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; Michael M. Bell (May 31, 2018). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2018" (PDF). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; Michael M. Bell (July 2, 2018). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2018" (PDF). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (July 5, 2018). "July Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2018" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; Michael M. Bell (August 2, 2018). "Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike probability for 2018" (PDF). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (August 6, 2018). "August Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2018" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Cecelia Hanley (August 9, 2018). "NOAA revises hurricane predictions, says Atlantic will have below average season". KCBD. Archived from the original on August 10, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "Here comes La Nina, El Nino's flip side, but it will be weak". ABC News. November 9, 2017. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- Christopher W. Landsea (2019). "Subject: E11) How many tropical cyclones have there been each year in the Atlantic basin? What years were the greatest and fewest seen?". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- "Destructive 2018 Atlantic hurricane season draws to an end". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. November 28, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "Monthly Tropical Weather Summary". National Hurricane Center. December 1, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

-

- Robbie Berg (October 17, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Alberto (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- Eric S. Blake (December 14, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Chris (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- Stacy R. Stewart; Robbie J. Berg (May 30, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Florence (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Kelly Healey (September 10, 2018). "Man drowns while swimming in New Smyrna Beach amid rip current warning, officials say". WFTV. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- Kevin Williams; Melonie Holt (September 12, 2018). "Hurricane Florence updates: Gas stations run dry in parts of South Carolina". WFTV. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Daniel P. Brown; Andrew S. Latto; Robbie J. Berg (February 19, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Gordon (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- Mohamed Moro Sacko (September 6, 2018). "Siguiri : Trois morts suite à des pluies duliviennnes à Doko". Guinea News (in French). Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- RA IV Hurricane Committee Members (February 12, 2019). Country Report: Saint Lucia (PDF) (Report). Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- British Caribbean Territories (February 14, 2019). Country Report: British Caribbean Territories (PDF) (Report). Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- Richard J. Pasch; David P. Roberts (March 29, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Leslie (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Inondations dans l'Aude : deux semaines après le drame, le bilan s'alourdit à 15 morts". Actu.fr (in French). October 30, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Global Catastrophe Recap October 2018 (PDF) (Report). AON. November 7, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- John L. Beven II; Robbie Berg; Andrew Hagan (May 17, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Michael (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (September 9, 2018). "The Atlantic now has 3 hurricanes at the same time: #Florence, #Helene and #Isaac" (Tweet). Retrieved February 14, 2020 – via Twitter.

- John L. Beven II; Robbie Berg; Andrew Hagan (May 17, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Michael (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Hurricane Camille – August 17, 1969 (Report). National Weather Service Mobile, Alabama. August 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Robbie Berg (October 17, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Alberto (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- "Tormenta subtropical "Alberto" solo dejó inundaciones leves en Yucatán" (in Spanish). May 26, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "Ha sido rápida la respuesta a los daños ocasionados por la tormenta subtropical Alberto". Government of Cuba (in Spanish). ReliefWeb. June 26, 2018. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- Cuba se recupera de las intensas lluvias. Government of Cuba (Report) (in Spanish). ReliefWeb. June 12, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "Tropical Storm Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- Lixion A. Avila and Cody L. Fritz (September 20, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Beryl (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Marshall Shepherd (July 6, 2018). "Beryl Is The First Atlantic Hurricane Of 2018 – But Keep An Eye On The Carolinas Too". Forbes. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- "L'onde tropicale Beryl balaie la Guadeloupe le 9 juillet avec de fortes pluies orageuses". Keraunos (in French). July 9, 2018. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- "Más de 8,000 dominicanos, desplazados por las lluvias causadas por Beryl". Panamá América (in Spanish). EFE. July 10, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Global Catastrophe Recap July 2018 (PDF) (Report). Aon Benfield. August 9, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- Eric S. Blake (December 14, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Chris (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- Lixion A. Avila (July 7, 2018). "Tropical Depression Three Discussion Number 5". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- John L. Beven (July 10, 2018). "Hurricane Chris Discussion Number 18". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- Kacey Cunningham (July 10, 2018). "Beachfront homes take pounding from Hurricane Chris". WRAL-TV. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- "Post-tropical storm Chris veers west, drenching Gander". CBC. July 13, 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- "Daily Data Report for July 2018". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Stacy R. Stewart (August 4, 2018). "NHC Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook Archive". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Richard J. Pasch (March 28, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Debby (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- John L. Beven II (April 2, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Ernesto (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Daniel P. Brown (August 17, 2018). "Tropical Storm Ernesto Discussion Number 11". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Stephen White (August 19, 2018). "UK Weather forecast: August Bank Holiday weekend conditions 'uncertain' with Brits either facing rain or shine". Daily Mirror. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Stacy R. Stewart; Robbie J. Berg (May 30, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Florence (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- Sam Lillo [@splillo] (September 5, 2018). "Intensity at 18z has been increased to 115kt – Florence is officially a category 4 hurricane. At 22.4N / 46.2W, this also makes Florence the furthest north category 4 hurricane east of 50W ever recorded in the Atlantic" (Tweet). Retrieved January 30, 2020 – via Twitter.

- Kelly Healey (September 10, 2018). "Man drowns while swimming in New Smyrna Beach amid rip current warning, officials say". WFTV. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- Kevin Williams; Melonie Holt (September 12, 2018). "Hurricane Florence updates: Gas stations run dry in parts of South Carolina". WFTV. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Daniel P. Brown; Andrew S. Latto; Robbie J. Berg (February 19, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Gordon (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- David J. Neal (September 3, 2018). "One dead as car crashes jam highways connecting Miami and Miami Beach". Miami Herald. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- Event Details: Flood (Report). National Climatic Data Center. 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- John P. Cangialosi (July 20, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Helene (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Mohamed Moro Sacko (September 6, 2018). "Siguiri : Trois morts suite à des pluies duliviennnes à Doko". Guinea News (in French). Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- "Passagem de tempestade tropical Helene provoca queda de árvores, postes e antenas de telecomunicações". ASemana (in Portuguese). September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (September 9, 2018). "Helene now has max winds of 85 mph at 27.2°W. In the satellite era (since 1966), the only Atlantic hurricane further east to be this strong in the tropics (south of 23.5°N) is Fred (2015)" (Tweet). Retrieved January 12, 2020 – via Twitter.

- Daniel Brown (September 14, 2018). "Tropical Storm Joyce Discussion Number 7". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- "Met Éireann briefing on Ex Tropical Storm Helene 4pm Monday 17th September – Met Éireann – The Irish Meteorological Service". Met Éireann. September 17, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- "Will tropical storm affect the UK?". Met Office. September 14, 2018. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- "UK weather: Storm Ali brings danger-to-life warning with 80mph winds". The Telegraph. September 18, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- David A. Zelinsky (January 30, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Isaac (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- "Tempête Isaac : en Martinique et en Guadeloupe, plus de peur que de mal". France 24 (in French). Agence France-Presse. September 14, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- Robbie Berg (January 30, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Joyce (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- Lixion A. Avila (November 9, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Eleven (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- Stacy R. Stewart (September 18, 2018). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Amy Campbell; Eric S. Blake (September 21, 2018). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". College Park, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Eric S. Blake (January 29, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Kirk (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- RA IV Hurricane Committee Members (February 12, 2019). Country Report: Saint Lucia (PDF) (Report). Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- Tropical Storm Kirk Situation Report #1 (PDF) (Report). Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency. September 28, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Poultry farmer loses 2000 chickens during storm". St. Lucia Times. September 30, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- British Caribbean Territories (February 14, 2019). Country Report: British Caribbean Territories (PDF) (Report). Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- Richard J. Pasch; David P. Roberts (March 29, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Leslie (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Eric S. Blake (October 12, 2018). "Hurricane Leslie Discussion Number 63". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Arquipélago da Madeira em "alerta máximo" devido ao furacão Leslie". Diário de Notícias (in Portuguese). October 12, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Marco Freitas (October 12, 2018). "Furacão Leslie: mais de 180 jogos cancelados na Madeira e duas exceções nas modalidades". O Jogo (in Portuguese). Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "'Zombie' storm Leslie smashes into Portugal". Agence France-Presse. October 14, 2018. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "Épisode pluvio-orageux exceptionnel dans l'Aude le 15 octobre". Keraunos (in French). October 15, 2018. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Inondations dans l'Aude : deux semaines après le drame, le bilan s'alourdit à 15 morts". Actu.fr (in French). October 30, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Global Catastrophe Recap October 2018 (PDF) (Report). AON. November 7, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Tres muertos y más de 1900 viviendas afectadas por lluvias". Confidencial (in Spanish). October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- "Al menos 9 muertos y miles de afectados por un temporal en Centroamérica". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). EFE. October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- "Huracán Michael deja daños significativos en Cuba". Conexión Capital (in Spanish). October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Hatzel Vela (October 9, 2018). "Hurricane Michael causes some destruction in western Cuba". WPLG. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- Stacy R. Stewart (March 22, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Nadine (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (October 9, 2018). "#Nadine has formed in the eastern tropical Atlantic" (Tweet). Retrieved February 14, 2020 – via Twitter.

- Daniel P. Brown (February 19, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Oscar (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "Tropical Cyclone Names#Atlantic". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Florence and Michael retired by the World Meteorological Organization (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 20, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

External links

- National Hurricane Center's website

- National Hurricane Center's Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook

- Tropical Cyclone Formation Probability Guidance Product

- Weather Underground tropical cyclone tracker

- Weather Underground Weather Map & Models