AirTrain JFK

AirTrain JFK is an 8.1-mile-long (13 km) elevated people mover system and airport rail link serving John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK Airport) in New York City. The driverless system operates 24/7 and consists of three lines and nine stations within the New York City borough of Queens. It connects the airport's terminals with the New York City Subway in Howard Beach, Queens, and with the Long Island Rail Road and the subway in Jamaica, Queens. Bombardier Transportation operates AirTrain JFK under contract to the airport's operator, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

| AirTrain JFK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Connects John F. Kennedy International Airport to various points within Queens, New York City | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | People mover/airport rail link | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Bombardier Transportation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | 32 × Bombardier Innovia ART 200[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ridership | 3,439,400 (2021)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | December 17, 2003 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 8.1 miles (13 km)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Elevated railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Third rail, 750 V DC[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 60 mph (97 km/h)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A railroad link to JFK Airport was first recommended in 1968. Various plans surfaced to build a JFK Airport rail connection until the 1990s, though these were not carried out because of a lack of funding. The JFK Express subway service and shuttle buses provided an unpopular transport system to and around JFK. In-depth planning for a dedicated transport system at JFK began in 1990, but was ultimately cut back from a direct rail link to an intra-borough people mover. Construction of the current people-mover system began in 1998. During construction, AirTrain JFK was the subject of several lawsuits, and an operator died during one of the system's test runs. The system opened on December 17, 2003, after many delays. Since then, several improvements have been proposed, including an extension to Manhattan. AirTrain JFK originally had ten stations, but one stop was closed in 2022.

All passengers entering or exiting at either Jamaica or Howard Beach must pay a $8.00 fare, while passengers traveling within the airport can ride for free. The system was originally projected to carry 4 million annual paying passengers and 8.4 million annual inter-terminal passengers every year. The AirTrain has consistently exceeded these projections since opening. In 2019, the system had over 8.7 million paying passengers and 12.2 million inter-terminal passengers.

History

Plan for direct rail connection

The first proposal for a direct rail link to JFK Airport was made in the mid-1940s, when a rail line was proposed for the median of the Van Wyck Expressway, connecting Midtown Manhattan with the airport. New York City parks commissioner Robert Moses, at the time an influential urban planner in the New York City area, refused to consider the idea.[6][7] In 1968, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) suggested extending the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) to the airport as part of the Program for Action, an ambitious transportation expansion program for the New York City area.[7][8][9] Ultimately, the rail link was canceled altogether due to the New York City fiscal crisis of 1975.[10] Another proposal, made by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in 1987, called for a rail line to connect all of JFK Airport's terminals with a new $500 million transportation center.[11] The Port Authority withdrew its plans in 1990 after airlines objected that they could not fund the proposal.[12][13]

In 1978, the MTA started operating the JFK Express, a premium-fare New York City Subway service that connected Midtown Manhattan to the Howard Beach–JFK Airport station.[7][14][15] The route carried subway passengers to the Howard Beach station,[7][16] where passengers would ride shuttle buses to the airport.[15][17] The shuttle buses transported passengers between the different airport terminals within JFK's Central Terminal Area, as well as between Howard Beach and the terminals.[18] The JFK Express service was unpopular with passengers because of its high cost, and because the buses often got stuck in traffic.[19][20] The service was ultimately canceled in 1990.[7][19]

By the 1990s, there was demand for a direct link between Midtown Manhattan and JFK Airport, which are 15 miles (24 km) apart by road. During rush hour, the travel time from JFK to Manhattan could average up to 80 minutes by bus; during off-peak hours, a New York City taxi could make that journey in 45 minutes, while a bus could cover the same distance in an hour.[9] The Port Authority, foreseeing economic growth for the New York City area and increased air traffic at JFK, began planning for a direct rail link from the airport to Manhattan. In 1991, the Port Authority introduced a Passenger Facility Charge (PFC),[9] a $3 tax on every passenger departing from JFK,[9][13][21] which would provide $120 million annually.[22]

In 1990, the MTA proposed a $1.6 billion rail link to LaGuardia and JFK airports, which would be funded jointly by federal, state, and city government agencies.[20] The rail line was to begin in Midtown Manhattan, crossing the East River into Queens via the Queensboro Bridge.[23] It would travel to LaGuardia Airport, then make two additional stops at Shea Stadium and Jamaica before proceeding to JFK.[20][24][25] After the Port Authority found that the ridership demand might not justify the cost of the rail link, the MTA downgraded the project's priority.[26] The proposal was supported by governor Mario Cuomo[13] and Queens borough president Claire Shulman.[19][23] The transport advocacy group Regional Plan Association (RPA) called the plan "misguided", and the East Side Coalition on Airport Access's executive director said, "We are going to end up with another [...] uncompleted project in this city."[23]

The Port Authority started reviewing blueprints for the JFK rail link in 1992.[25][22] At the time, it was thought that the link could be partially open within six years.[22] In 1994, the Port Authority set aside $40 million for engineering and marketing of the new line, and created an environmental impact statement (EIS).[27] The project's budget had grown to $2.6 billion by that year.[27] The EIS, conducted by the New York State Department of Transportation and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), found the plan to be feasible, though the project attracted opposition from area residents and advocacy groups.[28]

The project was to start in 1996, but there were disputes over where the Manhattan terminal should be located. The Port Authority had suggested the heavily trafficked corner of Lexington Avenue and 59th Street,[23][25][27] though many nearby residents opposed the Manhattan terminal outright.[29] The Port Authority did not consider a connection to the more-highly used Grand Central Terminal or Penn Station because such a connection would have been too expensive and complicated.[23] To pay for the project, the Port Authority would charge a one-way ticket price of between $9 and $12.[23] By February 1995, the cost of the planned link had increased to over $3 billion in the previous year alone. As a result, the Port Authority considered abridging the rail link plan, seeking federal and state funding, partnering with private investors, or terminating the line at a Queens subway station.[23]

Curtailment of plan

The direct rail connection between Manhattan, LaGuardia Airport, and JFK Airport was canceled outright in mid-1995.[30][31][32] The plan had failed to become popular politically, as it would have involved increasing road tolls and PATH train fares to pay for the new link.[31] In addition, the 1990s economic recession meant that there was little chance that the Port Authority could fund the project's rising price.[31][33] Following the cancellation, the planned connection to JFK Airport was downsized to a 7.5-mile (12.1 km) monorail or people mover, which would travel between Howard Beach and the JFK terminals.[19] The Port Authority initially proposed building a $827 million monorail, similar to AirTrain Newark at Newark Airport, which would open the following year.[34] In August 1995, the FAA approved the Port Authority's request to use the PFC funds for the monorail plan[33] (the agency had already collected $114 million, and was planning to collect another $325 million).[32] After the monorail was approved, the Port Authority hoped to begin construction in 1997 and open the line by 2002.[32][33]

The Port Authority voted to proceed with the scaled-down system in 1996.[30][35] Its final environmental impact statement (FEIS) for the JFK people mover, released in 1997, examined eight possibilities.[36] Ultimately, the Port Authority opted for a light rail system with the qualities of a people mover, tentatively called the "JFK Light Rail System".[37] It would replace the shuttle buses, running from the airport terminals to either Jamaica or Howard Beach.[30][3] The FEIS determined that an automated system with frequent headways was the best design.[38][39][40] Although there would not be a direct connection to Manhattan, the Port Authority estimated it would halve travel time between JFK and Midtown, with the journey between JFK and Penn Station taking one hour.[30] According to The New York Times, in the 30 years between the first proposal and the approval of the light rail system, 21 recommendations for direct rail links to New York-area airports had been canceled.[30][39]

While Governor Pataki supported the revised people-mover plan, Mayor Rudy Giuliani voiced his opposition on the grounds that the city would have to contribute $300 million, and that it was not a direct rail link from Manhattan, and thus would not be profitable because of the need to transfer from Jamaica.[39][41][42] The Port Authority was originally planning to pay for only $1.2 billion of the project, and use the other $300 million to pay the rent at the airport instead.[39][41] In order to give his agreement, Giuliani wanted the Port Authority to study extending the Astoria elevated to LaGuardia Airport, as well as making the light-rail system compatible with the subway or LIRR to allow possible future interoperability.[43] He agreed to the plan in 1997 when the state agreed to reimburse the city for its share of the system's cost.[39][44] As part of the agreement, the state would also conduct a study on a similar train link to LaGuardia Airport.[44] By that time, the Port Authority had collected $441 million in PFC funds.[41]

In 1999, the RPA published a report in which it recommended the construction of new lines and stations for the New York City Subway. The plan included one service that would travel from Grand Central Terminal to JFK Airport via the JFK Light Rail.[45] Ultimately, the MTA rejected the RPA's proposal.[46]

Construction

The Port Authority could only use the funds from the Passenger Facility Charge to make improvements that exclusively benefited airport passengers. As a result, only the sections linking Jamaica and Howard Beach to JFK Airport were approved and built, since it was expected that airport travelers would be the sole users of the system.[38] The federal government approved the use of PFC funds for the new light rail system in February 1998. Some $200 million of the project's cost was not eligible to be funded from the PFC tax because, according to the FAA, the tax funds could not be used to pay for "any costs resulting from an over-designed system", such as fare collection systems.[47]

Construction of the system began in May 1998.[48][49] Most of the system was built one span at a time, using cranes mounted on temporary structures that erected new spans as they progressed linearly along the structures. Several sections were built using a balanced cantilever design, where two separate spans were connected to each other using the span-by-span method.[50] The Jamaica branch's location above the median of the busy Van Wyck Expressway, combined with the varying length and curves of the track spans, caused complications during construction. One lane of the Van Wyck had to be closed in each direction during off-peak hours, causing congestion.[49] By the end of 1999, the columns in the Van Wyck's median were being erected.[51] The project also included $80 million of tunnels within the airport, which was built using a cut-and-cover method. Two shifts of workers excavated a trench measuring 25 feet (7.6 m) deep, 100 feet (30 m) wide, and 1,000 feet (300 m) long. The water table was as shallow as 5 feet (1.5 m) beneath the surface, so contractors pumped water out of the trench during construction. For waterproofing, subcontractor Trevi-Icos Inc. poured a "U"-shaped layer of grout, measuring 80 feet (24 m) wide and between 50 and 90 feet (15 and 27 m) deep.[52]

The route ran mostly along existing rights-of-way, but three commercial properties were expropriated and demolished to make way for new infrastructure.[53] Members of the New York City Planning Commission approved the condemnation of several buildings along the route in May 1999 but voiced concerns about the logistics of the project. These concerns included the projected high price of the tickets, ridership demand, and unwieldy transfers at Jamaica.[54]

Though community leaders supported the project because of its connections to the Jamaica and Howard Beach stations, almost all the civic groups along the Jamaica branch's route opposed it due to concerns about nuisance, noise, and traffic.[54] There were multiple protests against the project; during one such protest in 2000, a crane caught fire in a suspected arson.[55] Homeowners in the vicinity believed the concrete supports would lower the value of their houses.[49] Residents were also concerned about the noise that an elevated structure would create;[19] according to a 2012 study, the majority of residents' complaints were due to "nuisance violations".[49] The Port Authority responded to residents' concerns by imposing strict rules regarding disruptive or loud construction activity, as well as implementing a streamlined damage claim process to compensate homeowners.[56] Through 2002, there were 550 nuisance complaints over the AirTrain's construction, of which 98 percent had been resolved by April of that year.[57] Not all community boards saw a high level of complaints; Queens Community Board 12, which includes the neighborhood of South Jamaica along the AirTrain's route, recorded few complaints about the construction process.[58]

The Air Transportation Association of America (ATA) filed a federal lawsuit in January 1999 alleging misuse of PFC funds. In March, a federal judge vacated the project's approval because the FAA had incorrectly continued to collect and make use of comments posted after the deadline for public comment, but found that the PFC funds had not been misused.[59][60] The FAA opened a second request for public comment and received a second approval.[60][61] In 2000, two local advocacy groups filed a second federal lawsuit, claiming that the FEIS had published misleading statements about the effects of the elevated structure on southern Queens neighborhoods.[62] The ATA and the two advocacy groups appealed the funding decision.[63] The ATA later withdrew from the lawsuit, but one of the advocacy groups proceeded with the appeal and lost.[63][64]

By the time the appeal was decided in October 2000, two-thirds of the system's viaduct structures had been erected.[63] Construction progressed quickly, and the system was ready for its first test trains by that December.[62] In May 2001, a $75 million renovation of the Howard Beach station was completed;[65] the rebuilt station contained an ADA-compliant transfer to and from the AirTrain.[66] The same month, work started on a $387 million renovation of the Jamaica LIRR station, which entailed building a transfer passageway to the AirTrain.[65][66] Though the Jamaica station's rehabilitation was originally supposed to be finished by 2005,[57] it was not completed until September 2006.[67] Two AirTrain cars were delivered and tested after the system's guideway rails were complete by March 2001.[58] The guideways themselves, between the rails, were completed in August 2001.[68]

Opening and effects

The Port Authority predicted that the AirTrain's opening would create 118 jobs at JFK Airport.[69] Service was originally planned to begin on the Howard Beach branch in October 2002,[48][57] followed by the Jamaica branch in 2003,[57][70] but was delayed because of several incidents during testing.[71] In July 2002, three workers were injured during an AirTrain derailment,[71] and in September 2002, a train operator died in another derailment.[51][72] The National Transportation Safety Board's investigation of the second crash found that the train had sped excessively on a curve.[73][74] As a result, the opening was postponed until June 2003,[75] and then to December 17, 2003, its eventual opening date.[51][76]

Southeast Queens residents feared the project could become a boondoggle,[56] as the construction cost of the system had increased to $1.9 billion.[21][77] Like other Port Authority properties, the AirTrain did not receive subsidies from the state or city for its operating costs. This was one of the reasons cited for the system's relatively high initial $5 fare, which was more than twice the subway's fare at the time of the AirTrain's opening.[78]

Several projects were developed in anticipation of the AirTrain. By June 2003, a 50,000-square-foot (4,600 m2), 16-story building was being planned for Sutphin Boulevard across from the Jamaica station. Other nearby projects built in the preceding five years included the Jamaica Center Mall, Joseph P. Addabbo Federal Building, the Civil Court, and a Food and Drug Administration laboratory and offices.[79] After AirTrain JFK began operations, Jamaica saw a boom in commerce. A 15-screen movie theater opened in the area in early 2004, and developers were also planning a 13-floor building in the area.[80] A proposed hotel above the AirTrain terminal was canceled after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.[80]

In 2004, the city proposed rezoning 40 blocks of Jamaica, centered around the AirTrain station, as a commercial area. The mixed-use "airport village" was to consist of 5 million square feet (460,000 m2) of space. According to the RPA, the rezoning was part of a proposal to re-envision Jamaica as a "regional center" because of the area's high usage as a transit hub. During the average weekday, 100,000 LIRR riders and 53,000 subway riders traveled to or from Jamaica. In addition, the Port Authority had estimated that the AirTrain JFK would carry 12.4 million passengers a year.[80]

Plans to extend the AirTrain to Manhattan were examined even before the system's opening.[81] Between September 2003 and April 2004, several agencies, including the MTA and the Port Authority, conducted a feasibility study of the Lower Manhattan–Jamaica/JFK Transportation Project, which would allow subway or LIRR trains to travel directly from JFK Airport to Manhattan.[82] The study examined 40 alternatives,[83] but the project was halted in 2008 before an environmental impact statement could be created.[84]

Renovation of JFK Airport

On January 4, 2017, the office of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a $7–10 billion plan to renovate JFK Airport.[85][86] As part of the project, the AirTrain JFK would either see lengthened trainsets or a direct track connection to the rest of New York City's transportation system, and a direct connection between the AirTrain, LIRR, and subway would be built at Jamaica station.[87] Shortly after Cuomo's announcement, the Regional Plan Association published an unrelated study for a possible direct rail link between Manhattan and JFK Airport.[88][89] Yet another study in September 2018, published by the MTA, examined alternatives for an LIRR rail link to JFK as part of a possible restoration of the abandoned Rockaway Beach Branch.[90]

In July 2017, Cuomo's office began accepting submissions for master plans to renovate the airport.[91][92] A year later, in October 2018, Cuomo released details of the project, whose cost had grown to $13 billion. The improvements included lengthening AirTrains as well as adding lanes to the Van Wyck Expressway.[93][94] The Terminal 2 station was closed on July 11, 2022, due to construction at JFK Airport and demolished shortly thereafter;[95] the Terminal 1 station was renamed Terminals 1 & 2.[96]

System

Routes

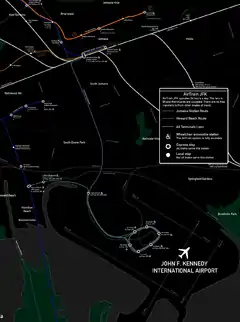

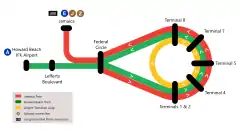

AirTrain JFK connects the airport's terminals and parking areas with the Howard Beach and Jamaica stations. It runs entirely within the New York City borough of Queens. The system consists of three routes: two connecting the terminals with either the Howard Beach or Jamaica stations, and one route looping continuously around the central terminal area.[97][98] It is operated by Bombardier under contract to the Port Authority.[69]

The Howard Beach Train route (colored green on the official map) begins and ends at the Howard Beach–JFK Airport station, where there is a direct transfer to the New York City Subway's A train.[1] It makes an additional stop at Lefferts Boulevard, where passengers can transfer to parking lot shuttle buses; the Q3 bus to Jamaica; the B15 bus to Brooklyn; and the limited-stop Q10 bus.[97][99] The segment from Howard Beach to Federal Circle, which is about 1.8 miles (2.9 km) long, passes over the long-term and employee parking lots.[100]

The Jamaica Train route (colored red on the official map) begins and ends at the Jamaica station, adjacent to the Long Island Rail Road platforms there. The Jamaica station contains a connection to the Sutphin Boulevard–Archer Avenue–JFK Airport station on the New York City Subway's E, J, and Z trains.[1][101] The AirTrain and LIRR stations contain transfers to the subway, as well as to ground-level bus routes.[97][98] West of Jamaica, the line travels above the north side of 94th Avenue before curving southward onto the Van Wyck Expressway. The segment from Jamaica to Federal Circle is about 3.1 miles (5.0 km) long.[100]

The Howard Beach Train and Jamaica Train routes merge at Federal Circle for car rental companies and shuttle buses to hotels and the airport's cargo areas. South of Federal Circle, the routes share track for 1.5 miles (2.4 km) and enter a tunnel before the tracks separate in two directions for the 2-mile (3.2 km) terminal loop.[102] Both routes continue counterclockwise around the loop, stopping at Terminals 1 & 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8 in that order.[98] A connection to the Q3 local bus is available at Terminal 8.[97][99] The travel time from either Jamaica or Howard Beach to the JFK terminals is about eight minutes.[103]

The Airport Terminals Loop (colored gold on the official map), an airport terminal circulator, serves the terminals. It makes a continuous clockwise loop around the terminals, operating in the opposite direction to the Howard Beach Train and Jamaica Train routes.[97][98] The terminal area loop is 1.8 miles (2.9 km) long.[3]

Trains to and from Jamaica and Howard Beach were originally planned to run every two minutes during peak hours, with alternate trains traveling to each branch.[104] The final environmental impact statement projected that trains in the central terminal area would run every ninety seconds.[105] By 2014 actual frequencies were much lower: each branch was served by one train every seven to 12 minutes during peak hours. Trains arrived every 10 to 15 minutes on each branch during weekdays; every 15 to 20 minutes during late nights; and every 16 minutes during weekends.[106]

Stations

All AirTrain JFK stations contain elevators and are compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA).[107] Each platform is 240 feet (73 m) long and can fit up to four cars.[4] The stations include air conditioning, as well as platform screen doors to protect passengers and to allow the unmanned trains to operate safely.[1][38] Each station also contains safety systems such as CCTV cameras, alarms, and emergency contact points, and is staffed by attendants.[38]

All the stations have island platforms except for Federal Circle, which has a bi-level split platform layout.[98] The Jamaica and Howard Beach stations are designed as "gateway stations" to give passengers the impression of entering the airport.[108] There are also stations at Lefferts Boulevard, as well as Terminals 1 & 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8. Three former terminals, numbered 3, 6, and 9, were respectively served by the stations that were later renamed Terminals 2, 5, and 8.[98][109] The four stations outside the Central Terminal Area were originally designated with the letters A–D alongside their names;[109] the letters were later dropped.[107] The Terminal 1 station was also renamed Terminals 1 & 2 in 2022.[96]

The Jamaica station was designed by Voorsanger Architects, and Robert Davidson of the Port Authority's in-house architecture department designed the Howard Beach station.[51] Most stations in the airport are freestanding structures connected to their respective terminal buildings by an aerial walkway. Access to Terminal 2 requires passengers to exit the Terminals 1 & 2 station and use crosswalks at street level,[96] while the Terminal 4 station is inside the terminal building itself.[110]

| Station[107] | Lines[107] | Connections[99][106] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Howard Beach 40.661043°N 73.829455°W |

Howard Beach Train |

|

Originally designated as Station A[109] |

| Lefferts Boulevard 40.661374°N 73.822660°W |

|

Originally designated as Station B[109] | |

| Federal Circle 40.659898°N 73.803602°W |

|

|

Originally designated as Station C[109] |

| Jamaica 40.69904°N 73.80807°W |

Jamaica Train |

|

Originally designated as Station D[109] |

| Terminals 1 & 2 40.643577°N 73.789348°W |

|

|

Originally named Terminal 1;[109] renamed after the closure of Terminal 2 station in July 2022[96] |

| Terminal 4 40.643974°N 73.782273°W |

|

||

| Terminal 5 40.646878°N 73.780067°W |

|

Originally named Terminals 5/6[109] | |

| Terminal 7 40.648266°N 73.783422°W |

|

||

| Terminal 8 40.646781°N 73.788709°W |

|

Originally named Terminals 8/9[109] |

Tracks and infrastructure

The AirTrain has a total route length of 8.1 miles (13.0 km).[3] The system consists of 6.3 miles (10.1 km) of single-track guideway viaducts and 3.2 miles (5.1 km) of double-track guideway viaducts.[111] AirTrain JFK is mostly elevated, though there are short segments that run underground or at ground level. The elevated sections were built with precast single and dual guideway spans, the underground sections used cut-and-cover, and the ground-level sections used concrete ties and ballast trackbeds. The single guideway viaducts carry one track each and are 19 feet 3 inches (5.87 m) wide, while the double guideway viaducts carry two tracks each and are 31 feet 0 inches (9.45 m) wide. Columns support the precast concrete elevated sections at intervals of up to 40 feet (12 m).[4] The elevated structures use seismic isolation bearings and soundproof barriers to protect from small earthquakes as well as prevent noise pollution.[50] AirTrain JFK's tunnels, all within the airport, pass beneath two taxiways and several highway ramps.[52]

The AirTrain runs on steel tracks[105] that are continuously welded across all joints except at the terminals; the guideway viaducts are also continuously joined.[112] Trains use double crossovers at the Jamaica and Howard Beach terminals in order to switch to the track going in the opposite direction. There are also crossover switches north and south of Federal Circle, counterclockwise from Terminal 8, and clockwise from Terminal 1.[5]

The tracks are set at a gauge of 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm).[4] This enables possible future conversion to LIRR or subway use, or a possible connection to LIRR or subway tracks for a one-trip ride into Manhattan, since these systems use the same track gauge.[48][103][113][114] AirTrain's current rolling stock, or train cars, are not able to use either LIRR or subway tracks due to the cars' inadequate structural strength and the different methods of propulsion used on each system. In particular, the linear induction motor system that propels the AirTrain vehicles is incompatible with the traction motor manual-propulsion system used by LIRR and subway rolling stock.[114] If a one-seat ride is ever implemented, a hybrid-use vehicle would be needed to operate on both subway/LIRR and AirTrain tracks.[103][114]

There are seven electrical substations. The redundancy allows trains to operate even if there are power outages at one substation.[1] Since there are no emergency exits between stations, a control tower can automatically guide the train to its next stop in case of an emergency.[57]

Fares

AirTrain JFK is free to use for travel within the terminal area, as well as at the Lefferts Boulevard station, which is next to the long-term parking, and at the Federal Circle station, where there are car-rental shuttle buses and transfers to and from the airport hotels.[115] Passengers entering or leaving the system only via the Jamaica or Howard Beach stations must pay using MetroCard.[115][116] AirTrain JFK does not accept the OMNY fare-payment system,[117] nor does it accept any other forms of payment, such as cash.[116] In 2022, JFK Airport indicated in a Twitter post that OMNY would not be implemented on AirTrain JFK until 2024.[118]

AirTrain accepts pay-per-ride MetroCards for $8.00 for transiting through either the Jamaica or Howard Beach gates. The MetroCards are preloaded with monetary value and $8.00 is deducted for each use.[116] A $1 fee is charged for any new MetroCards.[115] Two types of AirTrain MetroCards can be purchased from vending machines at Jamaica and Howard Beach. The 30-Day AirTrain JFK MetroCard costs $40 and can be used for unlimited rides on the AirTrain for 30 days after first use.[116] The AirTrain JFK 10-Trip MetroCard costs $25 and can be used for ten trips on the AirTrain within 31 days from first use.[116] Both cards are only accepted on the AirTrain, and one trip is deducted for each use of the 10-Trip MetroCard.[115] Other types of unlimited MetroCards are not accepted on the AirTrain.[116]

An additional $2.75 fare is required for passengers transferring to local buses or the subway, since the MTA does not offer free transfers from the AirTrain. Passengers pay a total of $10.75 if they transfer between the AirTrain and MTA subways or buses at either Howard Beach or Jamaica. Patrons transferring from the AirTrain to a Penn Station-bound LIRR train at Jamaica pay $18.75 during peak hours, or $13.00 during off-peak hours and weekends, using the railroad's CityTicket program.[119]

The fare to enter or exit at Howard Beach and Jamaica was originally $5,[77] though preliminary plans included a discounted fare of $2 for airport and airline employees.[105] The original proposal also called for fare-free travel between airport terminals,[105] a recommendation that was ultimately implemented.[115] In June 2019, the Port Authority proposed raising AirTrain JFK's fare to $7.75,[120][121] and the fare increase was approved that September.[122] The new fares took effect on November 1, 2019,[123][124] representing the first fare raise in the system's history.[122] In November 2021, the Port Authority discussed plans to raise the fare again to $8;[125][126] the second fare increase took effect on March 1, 2022.[127]

Rolling stock

AirTrain JFK uses Bombardier Transportation's Innovia ART 200 rolling stock and technology. Similar systems are used on the SkyTrain in Vancouver, the Everline in Yongin, and the Kelana Jaya Line in Kuala Lumpur.[1] The computerized trains are fully automated and use a communications-based train control system with moving block signals to dynamically determine the locations of the trains.[1] AirTrain JFK is a wholly driverless system,[1] and it uses SelTrac train-signaling technology manufactured by Thales Group.[128] Trains are operated from and maintained at a 10-acre (4 ha) train yard between Lefferts Boulevard and Federal Circle, atop a former employee parking lot.[129] The system originally used pre-recorded announcements by New York City traffic reporter Bernie Wagenblast, a longtime employee of the Port Authority.[130][131]

The 32 individual, non-articulated Mark II vehicles operating on the line draw power from a 750 V DC top-running third rail. A linear induction motor pushes magnetically against an aluminum strip in the center of the track. The vehicles also have steerable trucks that can navigate sharp curves and steep grades, as well as align precisely with the platform doors at the stations.[1][132] The cars can run at up to 60 miles per hour (97 km/h),[5] and they can operate on trackage with a minimum railway curve radius of 230 feet (70 m).[4][5]

Each car is 57 feet 9 inches (17.60 m) long and 10 feet 2 inches (3.10 m) wide,[4] which is similar to the dimensions of rolling stock used on the New York City Subway's B Division. Trains can run in either direction and can consist of between one and four cars.[1] The cars contain two pairs of doors on each side, with each door opening being 10 feet 5 inches (3.18 m) wide.[4] An individual car has 26 seats and can carry up to 97 passengers with luggage, or 205 without luggage.[4] Because most passengers carry luggage, the actual operating capacity is between 75 and 78 passengers per car.[132]

Ridership

When AirTrain JFK was being planned, it was expected that 11,000 passengers per day would pay to ride the system between the airport and either Howard Beach or Jamaica, and that 23,000 more daily passengers would use the AirTrain to travel between terminals. This would amount to about 4 million paying passengers and 8.4 million in-airport passengers per year.[53] According to the FEIS, the system could accommodate over 3,000 daily riders from Manhattan, and its opening would result in approximately 75,000 fewer vehicle miles (121,000 kilometers) being driven each day.[133]

During the first month of service, an average of 15,000 passengers rode the system each day.[134] Though this figure was less than the expected daily ridership of 34,000,[134] the AirTrain JFK had become the second-busiest airport transportation system in the United States.[1] Within its first six months, AirTrain JFK had transported one million riders.[135]

In the decade after the AirTrain opened, it consistently experienced year-over-year ridership growth.[136][137] A New York Times article in 2009 observed that one possible factor in the AirTrain's increasing ridership was the $7.75 fare for AirTrain and subway, which was cheaper than the $52 taxi ride between Manhattan and JFK.[138] In 2019, there were 8.7 million passengers who paid to travel between JFK Airport and either Howard Beach or Jamaica. This represented an increase of more than 300 percent from the 2.6 million riders who paid during the first full year of operation, 2004.[136] An additional 12.2 million people were estimated to have ridden the AirTrain for free in 2019, placing total annual ridership at 20.9 million.[137] Amid a decline in air travel caused by the COVID-19 pandemic,[139] the AirTrain had 3.4 million total riders in 2021.[140]

See also

- AirTrain LaGuardia, a similar system planned at LaGuardia Airport

- AirTrain Newark, a similar system at Newark Liberty International Airport

- List of airport circulators

- Lists of rapid transit systems § North America

References

Citations

- "AirTrain JFK opens for service". Railway Gazette International. March 1, 2004. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2021" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. March 10, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 2.

- Bombardier Transportation 2004, p. 2.

- Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 3.

- Caro, Robert (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf. pp. 904–908. ISBN 978-0-394-48076-3. OCLC 834874.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 67.

- Metropolitan transportation, a program for action. Report to Nelson A. Rockefeller, Governor of New York. Metropolitan Commuter Transit Authority. February 29, 1968. pp. 23–24. Retrieved October 1, 2015 – via Internet Archive.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES2.

- "JFK rail link "not feasible," Ronan says" (PDF). The Daily News. Tarrytown, NY. Associated Press. April 28, 1976. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved September 11, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- Schmitt, Eric (February 2, 1987). "New York Airports: $3 Billion Program". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Goldberger, Paul (June 17, 1990). "Architecture View: Blueprint an Airport that Might Have Been". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Steinberg, Jacques (December 28, 1991). "Port Authority Plans Changes At Kennedy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Grynbaum, Michael M. (November 25, 2009). "If You Took the Train to the Plane, Sing the Jingle". City Room. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- "New "JFK Express" Service Begun in Howard Beach" (PDF). New York Leader Observer. September 28, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved July 22, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- UCL Bartlett 2011, p. 32.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 1.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, pp. 1–2.

- Herszenhorn, David M. (August 20, 1995). "Neighborhood Report: Howard Beach; Rethinking Plans For Those Trains To the Planes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Sims, Calvin (March 18, 1990). "M.T.A. Proposes Rail Line to Link Major Airports". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Topousis, Tom (November 26, 2000). "JFK Revamp Takes Off Facelift Will See Airport Flying into the Future". New York Post. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Dao, James (December 21, 1992). "Dream Train to Airports Takes Step Nearer Reality". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Levy, Clifford J. (February 1, 1995). "Port Authority May Scale Back Airport Rail Line". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Firestone 1994, p. 1.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 67–68.

- Strom, Stephanie (April 27, 1991). "Proposal to Link Airports by Rail Is Dealt Setback". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Lambert, Bruce (June 19, 1994). "Neighborhood Report: East Side; Site for Airport Link Is Disputed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Firestone 1994, pp. 1, 2.

- Firestone 1994, p. 2.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 68.

- Purnick, Joyce (June 5, 1995). "Metro Matters: The Train to the Plane Turns to Pie in the Sky". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Donohue, Pete (August 2, 1995). "JFK Light Rail Moves Forward". Daily News. New York. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Levy, Clifford J. (August 2, 1995). "A Monorail For Kennedy Is Granted Key Approval". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Levy, Clifford J. (July 23, 1995). "A Worry in Queens: Newark Airport's Monorail Might Work". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Sullivan, John (May 10, 1996). "Port Authority Approves a Rail Link to Kennedy Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES3.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES4.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES9.

- Newman, Andy (October 2, 1997). "Officials Agree On Modest Plan For a Rail Link To One Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, pp. ES11, 1.4.

- Macfarquhar, Neil (June 14, 1997). "Disagreement Over Rent Stalls Airport Rail Project". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Levy, Clifford J. (May 3, 1996). "Pataki Supports Two-Train Link to Kennedy Airport That GiulianiOpposes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Macfarquhar, Neil (March 13, 1997). "Agency Says J.F.K. Rail Plan Is Ready, but Mayor Balks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Feiden, Douglas (October 1, 1997). "JFK Rail Plan to Get Rudy's OK". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Regional Plan Association 1999, pp. 2, 12.

- Regional Plan Association 1999, pp. 17–19.

- Wald, Matthew L. (February 10, 1998). "Plan Approved for a Kennedy Rail Link". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Chan, Sewell (January 12, 2005). "Train to JFK Scores With Fliers, but Not With Airport Workers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- UCL Bartlett 2011, p. 22.

- Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 10.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 69.

- Oser, Alan S. (January 31, 1999). "How to Build With a Firm Foundation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, p. ES10.

- Herszenhorn, David M. (May 4, 1999). "Still Opposed, Planners Let Airport Link Go Ahead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Schwartzman, Bryan (June 8, 2000). "JFK Airtrain Project Fire Suspicious: Police". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, pp. 4–5.

- Dentch, Courtney (April 18, 2002). "AirTrain System Shoots for October Start Date". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Scheinbart, Betsy (March 29, 2001). "No Hitches in AirTrain Construction". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Text of Air Transport Association of America, Petitioner, v. Federal Aviation Administration, United States Department Oftransportation, and United States of America, Respondents. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Intervenor, 169 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir. 1999) is available from: Justia

- "FAA Statement on JFK Airport Light Rail System" (Press release). Federal Aviation Administration. August 16, 1999. Archived from the original on August 21, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 5.

- "POSTINGS: Work Continues on Rail Route to JFK; First Test Nears for AirTrain". The New York Times. September 17, 2000. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Bertrand, Donald (October 18, 2000). "Court Spurns AirTrain Lawsuit Upholds Use Of Airport Taxes". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Text of Southeast Queens Concerned Neighbors, Inc. and the Committee for Better Transit, Inc. Petitioners, v. Federal Aviation Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, and United States of America Respondents, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Intervenors. 229 F.3d 387 (2nd Cir. 2000) is available from: CourtListener FindLaw

- Scheinbart, Betsy (May 10, 2001). "AirTrain construction starts on Jamaica station". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 4.

- Ain, Stewart (September 9, 2006). "Jamaica Station, $300 Million Later". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Scheinbart, Betsy (August 23, 2001). "AirTrain's guideway above Van Wyck is complete". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Menchaca, Paul (July 18, 2002). "AirTrain Expected To Create 118 New Jobs At JFK Airport". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- Newman, Philip (July 18, 2002). "AirTrain on track to begin runs to Jamaica next year". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Boniello, Kathianne; Dentch, Courtney (October 3, 2002). "Feds investigate fatal AirTrain accident". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Tarek, Shams (October 4, 2002). "Following AirTrain Accident, A Community Mourns". Southeast Queens Press. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- Kennedy, Randy (October 18, 2002). "Inquiry Shows Speed of Test Run Caused Derailment of AirTrain". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Dentch, Courtney (October 10, 2002). "AirTrain Was Near Top Speed at Time of Crash: Feds". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Dentch, Courtney (February 27, 2003). "AirTrain May Start Service by June Despite Sept. Crash". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Luo, Michael (December 18, 2003). "Century After Wright Brothers, a Train to J.F.K." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Stellin, Susan (December 14, 2003). "Travel Advisory: A Train to the Plane, At Long Last". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 9.

- Dunlap, David W. (July 6, 2003). "Change at Jamaica". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- Holusha, John (February 29, 2004). "Commercial Property; Jamaica Seeks to Build on AirTrain". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Dentch, Courtney (February 12, 2004). "Agencies Seek Extension of AirTrain Service". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 7.

- Parsons/SYSTRA Engineering, Inc. (2004). "Feasibility Study: Final Report" (PDF). Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. pp. 6–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- Parsons/SYSTRA Engineering, Inc. (December 2008). "Lower Manhattan-Jamaica/JFK Transportation Project, Summary Report, Prepared for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and PANYNJ". Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2017 – via Scribd.

- Barone, Vincent (January 4, 2017). "JFK airport renovation proposal unveiled by Cuomo". am New York. Archived from the original on January 5, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- Kirby, Jen (January 5, 2017). "New York City's Second-Worst Airport Might Also Get an Upgrade". Daily Intelligencer. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- Airport Advisory Panel (January 4, 2017). "A Vision Plan for John F. Kennedy International Airport" (PDF). Government of New York. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 5, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017 – via Office of Governor Andrew Cuomo.

- "Creating a One-Seat Ride to JFK" (PDF). Regional Plan Association. January 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Plitt, Amy (January 6, 2017). "One-Seat Rides to JFK Airport Are a Reality in This Public Transit Proposal". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- SYSTRA (September 21, 2018). "Reactivating the Rockaway Beach Branch: LIRR RBB JFK Study - Phase Two JFK OSR Rail Study". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- SYSTRA (September 21, 2018). "Reactivating the Rockaway Beach Branch: LIRR RBB JFK Study - Phase Two JFK OSR Rail Study: Diagrams". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- "New York launches next stage in JFK Airport overhaul". Deutsche Welle. Reuters and Bloomberg. July 19, 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "Governor Cuomo Announces RFP for Planning and Engineering Firm to Implement JFK Airport Vision Plan". Government of New York. July 18, 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017 – via Office of Governor Andrew Cuomo.

- McGeehan, Patrick (October 4, 2018). "Cuomo's $13 Billion Solution to the Mess That Is J.F.K. Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- Barone, Vincent (October 4, 2018). "Cuomo: JFK Airport renovation includes central hub, 2 new terminals". Newsday. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- @JFKairport (July 11, 2022). "We're building a better JFK and the following are now CLOSED for construction activities:" (Tweet). Retrieved July 11, 2022 – via Twitter.

- "Bridges, Tunnels and Rail Advisory for July 5 to 7" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. July 2022. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- "AirTrain JFK". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, pp. 2–3.

- "Queens Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. August 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, p. 1.12.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, p. 3.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, p. 1.13.

- Arema 1999, p. 1.

- Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 2.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, p. 1.5.

- Port Authority 2015, pp. 1, 2.

- Port Authority 2015, p. 2.

- Arema 1999, pp. 2–3.

- Bombardier Transportation 2004, p. 1.

- Rafter, Domenick (May 30, 2013). "Delta Opens New JFK Terminal 4 Hub". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 25, 2017. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 1.

- Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 5.

- Gosling & Freeman 2012, pp. 3–4.

- Englot & Bakas 2002, pp. 12–13.

- "Cost and Tickets – AirTrain – Ground Transportation – John F. Kennedy International Airport". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on May 24, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- "MTA/New York City Transit: Fares and MetroCard". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- "How to get to JFK Airport on public transit". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- Garber, Nick (June 24, 2022). "OMNY's Delayed Rollout To JFK AirTrain Must Be Sped Up, Lawmakers Say". Queens, NY Patch. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- "AirTrain JFK". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- "Port Authority plans toll, fare hikes, $4 airport tax for taxis, app-based for-hire cars". ABC7 New York. June 25, 2019. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- Guse, Clayton (June 25, 2019). "Port Authority plans to jack up bridge, tunnel, AirTrain prices, add $4 airport tax for taxis and app-based rides". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- "Port Authority approves fare and toll hikes, including new fee for airport rides". Pix11 New York. September 26, 2019. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- Higgs, Larry (October 31, 2019). "Fare hikes from the Port Authority start Friday". nj. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- "1st phase of Port Authority toll and fare hikes start Friday". ABC7 New York. October 31, 2019. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- Duggan, Kevin (November 18, 2021). "Port Authority plans fare hike to $8 for AirTrains in 2022". amNewYork. Archived from the original on November 19, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- Guse, Clayton (November 18, 2021). "Port Authority seeks $8 AirTrain fare come 2022, a 25-cent hike". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 19, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- "Bridges, Tunnels and Rail Advisory for February 18 to 24" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- "SelTrac™ CBTC Signalling Projects" (PDF). Thales Group. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 1, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, pp. ES9, 1.18.

- Hamlett, Roz (January 12, 2017). "Bernie Wagenblast: The Voice of Public Transportation in the Region". PANYNJ PORTfolio. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "The Airport Voice Speaks to Metropolitan Airport News". Metropolitan Airport News. February 13, 2017. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- Englot & Bakas 2002, p. 4.

- EIS Volume 1 1997, pp. ES10–ES11.

- Dentch, Courtney (January 22, 2004). "AirTrain Ridership On Track to Meet Year-End Goal: PA". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Simon, Mallory (June 17, 2004). "AirTrain Awaits Millionth Rider Six Months Later". Times Ledger. Queens, NY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "Governor Cuomo Announces AirTrain JFK Reaches Record High Ridership in 2014". LongIsland.com. February 12, 2015. Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- "2019 Airport Traffic Report" (PDF). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. May 19, 2020. pp. 4, 61. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- Levere, Jane L. (August 10, 2009). "Trains and Vans May Beat Taxis to the Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- "JFK getting $9.5B for new international terminal". Crain's New York Business. December 13, 2021. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2021" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. March 10, 2022. p. 25. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

Bibliography

- "Advanced Rapid Transit System AirTrain JFK International Airport, New York, USA" (PDF). Bombardier Transportation. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- "AirTrain JFK: The Fast, Affordable Connection" (PDF). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. March 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- Englot, Joseph M.; Bakas, Paul T. (September 2002). "Performance/Design Criteria for the Airtrain JFK Guideway" (PDF). AREMA 2002 Annual Conference & Exposition. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2018.

- Firestone, David (July 31, 1994). "The Push Is On for Link to Airports: Port Authority Confident of Rail Plan Despite Opposition". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Gosling, Geoffrey D.; Freeman, Dennis (May 2012). "Case Study Report: John F. Kennedy International Airport AirTrain" (PDF). Mineta Transportation Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- JFK International Airport Light Rail System: Environmental Impact Statement. Vol. 1. Federal Aviation Administration; New York State Department of Transportation. 1997. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- JFK International Airport Light Rail System: Environmental Impact Statement. Vol. 2. Federal Aviation Administration; New York State Department of Transportation. 1997. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- JFK International Airport Light Rail System: Environmental Impact Statement. Vol. 3. Federal Aviation Administration; New York State Department of Transportation. 1997. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- "MetroLink" (PDF). Regional Plan Association. January 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- "Project Profile; USA; New York Airtrain" (PDF). University College London Bartlett School of Planning. September 6, 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2006). New York 2000: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Bicentennial and the Millennium. New York: Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1-58093-177-9. OCLC 70267065. OL 22741487M.

- "The Airtrain Airport Access System John F. Kennedy International Airport" (PDF). American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association. 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

External links

| Google Maps Street View | |

|---|---|

![]() Media related to AirTrain JFK (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to AirTrain JFK (category) at Wikimedia Commons