Aloe vera

Aloe vera (/ˈæloʊ(i) vɛrə, vɪər-/)[3] is a succulent plant species of the genus Aloe.[4] It is widely distributed, and is considered an invasive species in many world regions.[4][5]

| Aloe vera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Plant with flower detail inset | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Asphodelaceae |

| Subfamily: | Asphodeloideae |

| Genus: | Aloe |

| Species: | A. vera |

| Binomial name | |

| Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

An evergreen perennial, it originates from the Arabian Peninsula, but grows wild in tropical, semi-tropical, and arid climates around the world.[4] It is cultivated for commercial products, mainly as a topical treatment used over centuries.[4][5] The species is attractive for decorative purposes, and succeeds indoors as a potted plant.[6]

It is used in many consumer products, including beverages, skin lotion, cosmetics, ointments or in the form of gel for minor burns and sunburns. There is little clinical evidence for the effectiveness or safety of Aloe vera extract as a cosmetic or topical drug.[5][7] The name derives from Latin as aloe and vera ("true").

Etymology and common names

The botanical name derives from Latin, aloe (also from Greek), having uncertain origin, and vera ("true") from Latin.[8] Common names use aloe with a region of its distribution, such as Chinese aloe, Cape aloe or Barbados aloe.[2][5][9][10]

Description

Aloe vera is a stemless or very short-stemmed plant growing to 60–100 centimetres (24–39 inches) tall, spreading by offsets.[4] The leaves are thick and fleshy, green to grey-green, with some varieties showing white flecks on their upper and lower stem surfaces.[11] The margin of the leaf is serrated and has small white teeth. The flowers are produced in summer on a spike up to 90 cm (35 in) tall, each flower being pendulous, with a yellow tubular corolla 2–3 cm (3⁄4–1+1⁄4 in) long.[11][12] Like other Aloe species, Aloe vera forms arbuscular mycorrhiza, a symbiosis that allows the plant better access to mineral nutrients in soil.[13]

Aloe vera leaves contain phytochemicals under study for possible bioactivity, such as acetylated mannans, polymannans, anthraquinone C-glycosides, anthrones, and other anthraquinones, such as emodin and various lectins.[14][15]

Taxonomy

The species has several synonyms: A. barbadensis Mill., Aloe indica Royle, Aloe perfoliata L. var. vera and A. vulgaris Lam.[16][17] Some literature identifies the white-spotted form of Aloe vera as Aloe vera var. chinensis;[18][19] and the spotted form of Aloe vera may be conspecific with A. massawana.[20] The species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753 as Aloe perfoliata var. vera,[21] and was described again in 1768 by Nicolaas Laurens Burman as Aloe vera in Flora Indica on 6 April and by Philip Miller as Aloe barbadensis some ten days after Burman in the Gardener's Dictionary.[22]

Techniques based on DNA comparison suggest Aloe vera is relatively closely related to Aloe perryi, a species endemic to Yemen.[23] Similar techniques, using chloroplast DNA sequence comparison and ISSR profiling have also suggested it is closely related to Aloe forbesii, Aloe inermis, Aloe scobinifolia, Aloe sinkatana, and Aloe striata.[24] With the exception of the South African species A. striata, these Aloe species are native to Socotra (Yemen), Somalia, and Sudan.[24] The lack of obvious natural populations of the species has led some authors to suggest Aloe vera may be of hybrid origin.[25]

Distribution

A. vera is considered to be native only to the south-east[26] Arabian Peninsula in the Al Hajar Mountains in north-eastern Oman.[27] However, it has been widely cultivated around the world, and has become naturalized in North Africa, as well as Sudan and neighboring countries, along with the Canary Islands, Cape Verde, and Madeira Islands.[16] It has also naturalized in the Algarve region of Portugal,[28][29] and in wild areas across southern Spain, especially in the region of Murcia.[30]

The species was introduced to China and various parts of southern Europe in the 17th century.[31] It is widely naturalized elsewhere, occurring in arid, temperate, and tropical regions of temperate continents.[4][27][32] The current distribution may be the result of cultivation.[20][33]

Cultivation

Aloe vera has been widely grown as an ornamental plant. The species is popular with modern gardeners as a topical medicinal plant[34] and for its interesting flowers, form, and succulence. This succulence enables the species to survive in areas of low natural rainfall, making it ideal for rockeries and other low water-use gardens.[11] The species is hardy in zones 8–11, and is intolerant of heavy frost and snow.[12][35] The species is relatively resistant to most insect pests, though spider mites, mealy bugs, scale insects, and aphid species may cause a decline in plant health.[36][37] This plant has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[38]

In pots, the species requires well-drained, sandy potting soil, and bright, sunny conditions. Aloe plants can turn red from sunburn under too much direct sun, though gradual acclimation may help.[39] The use of a good-quality commercial propagation mix or packaged "cacti and succulent mix" is recommended, as they allow good drainage.[40] Terra cotta pots are preferable as they are porous.[40] Potted plants should be allowed to completely dry before rewatering. When potted, aloes can become crowded with "pups" growing from the sides of the "mother plant". Plants that have become crowded can be divided and repotted to allow room for further growth, or the pups can be left with the mother plant.[39] During winter, Aloe vera may become dormant, during which little moisture is required.[39] In areas that receive frost or snow, the species is best kept indoors or in heated glasshouses.[12] Houseplants requiring similar care include haworthia and agave.[39]

There is large-scale agricultural production of Aloe vera in Australia,[41] Cuba, the Dominican Republic, China, Mexico,[42] India,[43] Jamaica,[44] Spain, where it grows well, even inland,[45] Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa,[46] along with the USA[47] to supply the cosmetics industry.[4]

Uses

Two substances from Aloe vera – a clear gel and its yellow latex – are used to manufacture commercial products.[7][34] Aloe gel typically is used to make topical medications for skin conditions, such as burns, wounds, frostbite, rashes, psoriasis, cold sores, or dry skin.[7][34] Aloe latex is used individually or manufactured as a product with other ingredients to be ingested for relief of constipation.[7][34] Aloe latex may be obtained in a dried form called resin or as "aloe dried juice".[48]

There is conflicting evidence regarding whether Aloe vera is effective as a treatment for wounds or burns.[5][34] There is some evidence that topical use of aloe products might relieve symptoms of certain skin disorders, such as psoriasis, acne, or rashes.[7][34]

Aloe vera gel is used commercially as an ingredient in yogurts, beverages, and some desserts,[49] but at high or prolonged doses, ingesting aloe latex or whole leaf extract can be toxic.[7][5][10] Use of topical aloe vera in small amounts is likely to be safe.[7][34]

Topical medication and potential side effects

Aloe vera may be prepared as a lotion, gel, soap or cosmetics product for use on skin as a topical medication.[5] For people with allergies to Aloe vera, skin reactions may include contact dermatitis with mild redness and itching, difficulty with breathing, or swelling of the face, lips, tongue, or throat.[5][10]

Dietary supplement

Aloin, a compound found in the semi-liquid latex of some Aloe species, was the common ingredient in over-the-counter (OTC) laxative products in the United States until 2002 when the Food and Drug Administration banned it because manufacturers failed to provide the necessary safety data.[7][5][50] Aloe vera has potential toxicity, with side effects occurring at some dose levels both when ingested and when applied topically.[5][10] Although toxicity may be less when aloin is removed by processing, Aloe vera ingested in high amounts may induce side effects, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea or hepatitis.[5][51] Chronic ingestion of aloe (dose of 1 gram per day) may cause adverse effects, including hematuria, weight loss, and cardiac or kidney disorders.[5]

Aloe vera juice is marketed to support the health of the digestive system, but there is neither scientific evidence nor regulatory approval for this claim.[7][5][34] The extracts and quantities typically used for such purposes are associated with toxicity in a dose-dependent way.[5][10]

Traditional medicine

Aloe vera is used in traditional medicine as a skin treatment. Early records of its use appear from the fourth millennium BCE.[5] It is also written of in the Juliana Anicia Codex of 512 CE.[49]: 9

Commodities

Aloe vera is used on facial tissues where it is promoted as a moisturizer and anti-irritant to reduce chafing of the nose. Cosmetic companies commonly add sap or other derivatives from Aloe vera to products such as makeup, tissues, moisturizers, soaps, sunscreens, incense, shaving cream, or shampoos.[49] A review of academic literature notes that its inclusion in many hygiene products is due to its "moisturizing emollient effect".[15]

Toxicity

Orally ingested non-decolorized aloe vera leaf extract was listed by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment among "chemicals known to the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity".[52]

Use of topical aloe vera is not associated with significant side effects.[7] Oral ingestion of aloe vera is potentially toxic,[5] and may cause abdominal cramps and diarrhea which in turn can decrease the absorption of drugs.[7]

Interactions with prescribed drugs

Ingested aloe products may have adverse interactions with prescription drugs, such as those used to treat blood clots, diabetes, heart disease and potassium-lowering agents (such as Digoxin), and diuretics, among others.[34]

Gallery

.JPG.webp) Leaf and inner gel

Leaf and inner gel Gel used for desserts

Gel used for desserts Es lidah buaya, an Indonesian Aloe vera iced drink

Es lidah buaya, an Indonesian Aloe vera iced drink Juice

Juice Cut leaf

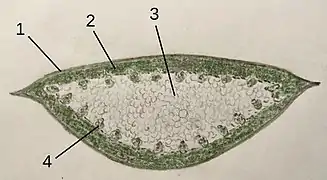

Cut leaf Diagram of leaf: 1 Cuticle, 2 Chloroplast parenchym, 3 Inner tissue, 4 Vascular bundles

Diagram of leaf: 1 Cuticle, 2 Chloroplast parenchym, 3 Inner tissue, 4 Vascular bundles Buds

Buds Flower buds

Flower buds Flowers

Flowers Plants of different sizes

Plants of different sizes A potted plant

A potted plant Sucker

Sucker

See also

- Medicinal plants

- Succulent plants

References

- Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. Tropicos.org

- "Aloe vera (L.)". The Plant List. 26 March 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- "aloe vera". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- "Aloe vera (true aloe)". Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. 13 February 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Aloe". Drugs.com. 30 December 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- Perkins, Cyndi. "Is Aloe a tropical plant?". SFGate. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "Aloe vera". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health. 1 October 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- "Aloe". Online Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper. 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- Liao Z, Chen M, Tan F, Sun X, Tang K (2004). "Microprogagation of endangered Chinese aloe". Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture. 76 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1023/a:1025868515705. S2CID 41623664.

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel (2007). "Final Report on the Safety Assessment of Aloe Andongensis Extract, Aloe Andongensis Leaf Juice, Aloe Arborescens Leaf Extract, Aloe Arborescens Leaf Juice, Aloe Arborescens Leaf Protoplasts, Aloe Barbadensis Flower Extract, Aloe Barbadensis Leaf, Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Extract, Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Juice, Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Polysaccharides, Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Water, Aloe Ferox Leaf Extract, Aloe Ferox Leaf Juice, and Aloe Ferox Leaf Juice Extract" (PDF). Int. J. Toxicol. 26 (Suppl 2): 1–50. doi:10.1080/10915810701351186. PMID 17613130. S2CID 86018076. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- Yates A. (2002) Yates Garden Guide. Harper Collins Australia

- Random House Australia Botanica's Pocket Gardening Encyclopedia for Australian Gardeners Random House Publishers, Australia

- Gong M, Wang F, Chen Y (2002). "[Study on application of arbuscular-mycorrhizas in growing seedings of Aloe vera]". Zhong Yao Cai (in Chinese). 25 (1): 1–3. PMID 12583231.

- King GK, Yates KM, Greenlee PG, Pierce KR, Ford CR, McAnalley BH, Tizard IR (1995). "The effect of Acemannan Immunostimulant in combination with surgery and radiation therapy on spontaneous canine and feline fibrosarcomas". J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 31 (5): 439–447. doi:10.5326/15473317-31-5-439. PMID 8542364.

- Eshun K, He Q (2004). "Aloe vera: a valuable ingredient for the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries—a review". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 44 (2): 91–96. doi:10.1080/10408690490424694. PMID 15116756. S2CID 21241302.

- "Aloe vera, African flowering plants database". Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de la Ville de Genève. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "Taxon: Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f." Germplasm Resources Information Network, United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- Wang H, Li F, Wang T, Li J, Li J, Yang X, Li J (2004). "[Determination of aloin content in callus of Aloe vera var. chinensis]". Zhong Yao Cai (in Chinese). 27 (9): 627–8. PMID 15704580.

- Gao W, Xiao P (1997). "[Peroxidase and soluble protein in the leaves of Aloe vera L. var. chinensis (Haw.)Berger]". Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi (in Chinese). 22 (11): 653–4, 702. PMID 11243179.

- Lyons G. "The Definitive Aloe vera, vera?". Huntington Botanic Gardens. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- Linnaeus, C. (1753). Species plantarum, exhibentes plantas rite cognitas, ad genera relatas, cum differentiis specificis, nominibus trivialibus, synonymis selectis, locis natalibus, secundum systema sexuale digestas. Vol. 2 pp. [i], 561–1200, [1–30, index], [i, err.]. Holmiae [Stockholm]: Impensis Laurentii Salvii.

- Newton LE (1979). "In defense of the name Aloe vera". The Cactus and Succulent Journal of Great Britain. 41: 29–30.

- Darokar MP, Rai R, Gupta AK, Shasany AK, Rajkumar S, Sunderasan V, Khanuja SP (2003). "Molecular assessment of germplasm diversity in Aloe spp. using RAPD and AFLP analysis". J Med. Arom. Plant Sci. 25 (2): 354–361.

- Treutlein J, Smith GF, van Wyk BE, Wink W (2003). "Phylogenetic relationships in Asphodelaceae (Alooideae) inferred from chloroplast DNA sequences (rbcl, matK) and from genomic finger-printing (ISSR)". Taxon. 52 (2): 193–207. doi:10.2307/3647389. JSTOR 3647389.

- Jones WD, Sacamano C. (2000) Landscape Plants for Dry Regions: More Than 600 Species from Around the World. California Bill's Automotive Publishers. USA.

- "World Checklist of Selected Plant Families: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew". wcsp.science.kew.org. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "Aloe vera". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Domingues de Almeida, J & Freitas (2006). "Exotic naturalized flora of continental Portugal – A reassessment" (PDF). core.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Gideon F Smith, Estrela Figueiredo (2009). "Aloe arborescens Mill. and Aloe Vera spreading in Portugal". Bradleya. bioone. doi:10.25223/brad.n27.2009.a4. hdl:2263/14380. S2CID 82872880.

- "Aloe Vera Cultivation in Murcia". 9 April 2015.

- Farooqi, A. A. and Sreeramu, B. S. (2001) Cultivation of Medicinal and Aromatic Crops. Orient Longman, India. ISBN 8173712514. p. 25.

- "Aloe vera". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- "Aloe vera (Linnaeus) Burman f., Fl. Indica. 83. 1768." in Flora of North America Vol. 26, p. 411

- "Aloe (Aloe vera)". Mayo Clinic. 17 September 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "BBC Gardening, Aloe vera". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- "Pest Alert: Aloe vera aphid Aloephagus myersi Essi". Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- "Kemper Center for Home Gardening: Aloe vera". Missouri Botanic Gardens, USA. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- "RHS Plant Selector Aloe vera AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Peerless, Veronica (2017). How Not to Kill Your Houseplant. DK Penguin Random House. pp. 38–39.

- Coleby-Williams, J (21 June 2008). "Fact Sheet: Aloes". Gardening Australia, Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- "Aloe vera producer signs $3m China deal". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 6 December 2005.

- "Korea interested in Dominican 'aloe vera'". DominicanToday.com—The Dominican Republic News Source in English. 7 July 2006. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008.

- Varma, Vaibhav (11 December 2005). "India experiments with farming medicinal plants". channelnewsasia.com.

- "Harnessing the potential of our aloe". Jamaica Gleaner, jamaica-gleaner.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- "Córdoba is the Spanish province with more aloe vera crops (translated from Spanish)". ABC-Córdoba. 23 August 2015.

- Mburu, Solomon (2 August 2007). "Kenya: Imported Gel Hurts Aloe Vera Market". allafrica.com.

- "US Farms, Inc. – A Different Kind of Natural Resource Company". resourceinvestor.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- "Assessment report on Aloe barbadensis Mill. and on Aloe (various species, mainly Aloe ferox Mill. and its hybrids), folii succus siccatus" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 22 November 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Reynolds, Tom (Ed.) (2004) Aloes: The genus Aloe (Medicinal and Aromatic Plants - Industrial Profiles. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0415306720

- Food Drug Administration, HHS (2002). "Status of certain additional over-the-counter drug category II and III active ingredients. Final rule". Fed Regist. 67 (90): 31125–7. PMID 12001972.

- Bottenberg MM, Wall GC, Harvey RL, Habib S (2007). "Oral aloe vera-induced hepatitis". Ann Pharmacother. 41 (10): 1740–3. doi:10.1345/aph.1K132. PMID 17726067. S2CID 25553593.

- "Chemicals Listed Effective December 4, 2015, as Known to the State of California to Cause Cancer: Aloe Vera, Non-Decolorized Whole Leaf Extract, and Goldenseal Root Powder". California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. 4 December 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

External links

- "Taxon: Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f." U.S. National Plant Germplasm System. Retrieved 8 March 2020.