Bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels.[1][2] Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vagina or anus, or through a puncture in the skin. Hypovolemia is a massive decrease in blood volume, and death by excessive loss of blood is referred to as exsanguination.[3] Typically, a healthy person can endure a loss of 10–15% of the total blood volume without serious medical difficulties (by comparison, blood donation typically takes 8–10% of the donor's blood volume).[4] The stopping or controlling of bleeding is called hemostasis and is an important part of both first aid and surgery. The use of cyanoacrylate glue to prevent bleeding and seal battle wounds was designed and first used in the Vietnam War. Today many medical treatments use a medical version of "super glue" instead of using traditional stitches used for small wounds that need to be closed at the skin level. This prevents the need of removing stitches at some future visit.

| Bleeding | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hemorrhaging, haemorrhaging, blood loss |

| |

| A bleeding wound in the finger | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, hematology |

| Complications | Exsanguination, hypovolemic shock, coma, shock |

Types

- Upper head

- Intracranial hemorrhage – bleeding in the skull.

- Cerebral hemorrhage – a type of intracranial hemorrhage, bleeding within the brain tissue itself.

- Intracerebral hemorrhage – bleeding in the brain caused by the rupture of a blood vessel within the head. See also hemorrhagic stroke.

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) implies the presence of blood within the subarachnoid space from some pathologic process. The common medical use of the term SAH refers to the nontraumatic types of hemorrhages, usually from rupture of a berry aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation (AVM).[5] The scope of this article is limited to these nontraumatic hemorrhages.

- Eyes

- Subconjunctival hemorrhage – bloody eye arising from a broken blood vessel in the sclera (whites of the eyes). Often the result of strain, including sneezing, coughing, vomiting or other kind of strain

- Nose

- Epistaxis – nosebleed

- Mouth

- Tooth eruption – losing a tooth

- Hematemesis – vomiting fresh blood

- Hemoptysis – coughing up blood from the lungs

- Lungs

- Pulmonary hemorrhage

- Gastrointestinal

- Upper gastrointestinal bleed

- Lower gastrointestinal bleed

- Occult gastrointestinal bleed

- Urinary tract

- Hematuria – blood in the urine from urinary bleeding

- Gynecologic

- Vaginal bleeding

- Postpartum hemorrhage

- Breakthrough bleeding

- Ovarian bleeding – This is a potentially catastrophic and not so rare complication among lean patients with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing transvaginal oocyte retrieval.[6]

- Vaginal bleeding

- Anus

- Melena – upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- Hematochezia – lower gastrointestinal bleeding, or brisk upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- Vascular

- Ruptured aneurysm

- Aortic transection

- Iatrogenic injury

Causes

Bleeding arises due to either traumatic injury, underlying medical condition, or a combination.

Traumatic injury

Traumatic bleeding is caused by some type of injury. There are different types of wounds which may cause traumatic bleeding. These include:

- Abrasion – Also called a graze, this is caused by transverse action of a foreign object against the skin, and usually does not penetrate below the epidermis.

- Excoriation – In common with Abrasion, this is caused by mechanical destruction of the skin, although it usually has an underlying medical cause.

- Hematoma – Caused by damage to a blood vessel that in turn causes blood to collect in an enclosed area.

- Laceration – Irregular wound caused by blunt impact to soft tissue overlying hard tissue or tearing such as in childbirth. In some instances, this can also be used to describe an incision.

- Incision – A cut into a body tissue or organ, such as by a scalpel, made during surgery.

- Puncture Wound – Caused by an object that penetrated the skin and underlying layers, such as a nail, needle or knife.

- Contusion – Also known as a bruise, this is a blunt trauma damaging tissue under the surface of the skin.

- Crushing Injuries – Caused by a great or extreme amount of force applied over a period of time. The extent of a crushing injury may not immediately present itself.

- Ballistic Trauma – Caused by a projectile weapon such as a firearm. This may include two external wounds (entry and exit) and a contiguous wound between the two.

The pattern of injury, evaluation and treatment will vary with the mechanism of the injury. Blunt trauma causes injury via a shock effect; delivering energy over an area. Wounds are often not straight and unbroken skin may hide significant injury. Penetrating trauma follows the course of the injurious device. As the energy is applied in a more focused fashion, it requires less energy to cause significant injury. Any body organ, including bone and brain, can be injured and bleed. Bleeding may not be readily apparent; internal organs such as the liver, kidney and spleen may bleed into the abdominal cavity. The only apparent signs may come with blood loss. Bleeding from a bodily orifice, such as the rectum, nose, or ears may signal internal bleeding, but cannot be relied upon. Bleeding from a medical procedure also falls into this category.

Medical condition

"Medical bleeding" denotes hemorrhage as a result of an underlying medical condition (i.e. causes of bleeding that are not directly due to trauma). Blood can escape from blood vessels as a result of 3 basic patterns of injury:

- Intravascular changes – changes of the blood within vessels (e.g. ↑ blood pressure, ↓ clotting factors)

- Intramural changes – changes arising within the walls of blood vessels (e.g. aneurysms, dissections, AVMs, vasculitides)

- Extravascular changes – changes arising outside blood vessels (e.g. H pylori infection, brain abscess, brain tumor)

The underlying scientific basis for blood clotting and hemostasis is discussed in detail in the articles, coagulation, hemostasis and related articles. The discussion here is limited to the common practical aspects of blood clot formation which manifest as bleeding.

Some medical conditions can also make patients susceptible to bleeding. These are conditions that affect the normal hemostatic (bleeding-control) functions of the body. Such conditions either are, or cause, bleeding diatheses. Hemostasis involves several components. The main components of the hemostatic system include platelets and the coagulation system.

Platelets are small blood components that form a plug in the blood vessel wall that stops bleeding. Platelets also produce a variety of substances that stimulate the production of a blood clot. One of the most common causes of increased bleeding risk is exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The prototype for these drugs is aspirin, which inhibits the production of thromboxane. NSAIDs inhibit the activation of platelets, and thereby increase the risk of bleeding. The effect of aspirin is irreversible; therefore, the inhibitory effect of aspirin is present until the platelets have been replaced (about ten days). Other NSAIDs, such as "ibuprofen" (Motrin) and related drugs, are reversible and therefore, the effect on platelets is not as long-lived.

There are several named coagulation factors that interact in a complex way to form blood clots, as discussed in the article on coagulation. Deficiencies of coagulation factors are associated with clinical bleeding. For instance, deficiency of Factor VIII causes classic hemophilia A while deficiencies of Factor IX cause "Christmas disease"(hemophilia B). Antibodies to Factor VIII can also inactivate the Factor VII and precipitate bleeding that is very difficult to control. This is a rare condition that is most likely to occur in older patients and in those with autoimmune diseases. Another common bleeding disorder is Von Willebrand disease. It is caused by a deficiency or abnormal function of the "Von Willebrand" factor, which is involved in platelet activation. Deficiencies in other factors, such as factor XIII or factor VII are occasionally seen, but may not be associated with severe bleeding and are not as commonly diagnosed.

In addition to NSAID-related bleeding, another common cause of bleeding is that related to the medication, warfarin ("Coumadin" and others). This medication needs to be closely monitored as the bleeding risk can be markedly increased by interactions with other medications. Warfarin acts by inhibiting the production of Vitamin K in the gut. Vitamin K is required for the production of the clotting factors, II, VII, IX, and X in the liver. One of the most common causes of warfarin-related bleeding is taking antibiotics. The gut bacteria make vitamin K and are killed by antibiotics. This decreases vitamin K levels and therefore the production of these clotting factors.

Deficiencies of platelet function may require platelet transfusion while deficiencies of clotting factors may require transfusion of either fresh frozen plasma or specific clotting factors, such as Factor VIII for patients with hemophilia.

Infection

Infectious diseases such as Ebola, Marburg virus disease and yellow fever can cause bleeding.

Diagnosis/Imaging

Dioxaborolane chemistry enables radioactive fluoride (18F) labeling of red blood cells, which allows for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of intracerebral hemorrhages.[7]

Classification

Blood loss

Hemorrhaging is broken down into four classes by the American College of Surgeons' advanced trauma life support (ATLS).[8]

- Class I Hemorrhage involves up to 15% of blood volume. There is typically no change in vital signs and fluid resuscitation is not usually necessary.

- Class II Hemorrhage involves 15-30% of total blood volume. A patient is often tachycardic (rapid heart beat) with a reduction in the difference between the systolic and diastolic blood pressures. The body attempts to compensate with peripheral vasoconstriction. Skin may start to look pale and be cool to the touch. The patient may exhibit slight changes in behavior. Volume resuscitation with crystalloids (Saline solution or Lactated Ringer's solution) is all that is typically required. Blood transfusion is not usually required.

- Class III Hemorrhage involves loss of 30-40% of circulating blood volume. The patient's blood pressure drops, the heart rate increases, peripheral hypoperfusion (shock) with diminished capillary refill occurs, and the mental status worsens. Fluid resuscitation with crystalloid and blood transfusion are usually necessary.

- Class IV Hemorrhage involves loss of >40% of circulating blood volume. The limit of the body's compensation is reached and aggressive resuscitation is required to prevent death.

This system is basically the same as used in the staging of hypovolemic shock.

Individuals in excellent physical and cardiovascular shape may have more effective compensatory mechanisms before experiencing cardiovascular collapse. These patients may look deceptively stable, with minimal derangements in vital signs, while having poor peripheral perfusion. Elderly patients or those with chronic medical conditions may have less tolerance to blood loss, less ability to compensate, and may take medications such as betablockers that can potentially blunt the cardiovascular response. Care must be taken in the assessment.

Massive hemorrhage

Although there is no universally accepted definition of massive hemorrhage, the following can be used to identify the condition: "(i) blood loss exceeding circulating blood volume within a 24-hour period, (ii) blood loss of 50% of circulating blood volume within a 3-hour period, (iii) blood loss exceeding 150 ml/min, or (iv) blood loss that necessitates plasma and platelet transfusion."[9]

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization made a standardized grading scale to measure the severity of bleeding.[10]

| Grade 0 | no bleeding; |

| Grade 1 | petechial bleeding; |

| Grade 2 | mild blood loss (clinically significant); |

| Grade 3 | gross blood loss, requires transfusion (severe); |

| Grade 4 | debilitating blood loss, retinal or cerebral associated with fatality |

Management

Acute bleeding from an injury to the skin is often treated by the application of direct pressure.[11] For severely injured patients, tourniquets are helpful in preventing complications of shock.[12] Anticoagulant medications may need to be discontinued and possibly reversed in patients with clinically significant bleeding.[13] Patients that have lost excessive amounts of blood may require a blood transfusion.[14]

Etymology

The word "Haemorrhage" (or hæmorrhage; using the æ ligature) comes from Latin haemorrhagia, from Ancient Greek αἱμορραγία (haimorrhagía, "a violent bleeding"), from αἱμορραγής (haimorrhagḗs, "bleeding violently"), from αἷμα (haîma, "blood") + -ραγία (-ragía), from ῥηγνύναι (rhēgnúnai, "to break, burst").[15]

See also

- Anaesthesia Trauma and Critical Care

- Aneurysm

- Autohemorrhaging

- Anemia

- Coagulation

- Contusion

- Exsanguination

- Hemophage

- Hemophilia

- Hematoma

- Istihadha

References

- "Bleeding Health Article". Healthline. Archived from the original on 2011-02-10. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- Roth, Elliot J. (2011). "Hemorrhage". Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 1234–1235. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-79948-3_2178. ISBN 978-0-387-79947-6.

Hemorrhage is active bleeding, in which blood escapes from the blood vessels, either into the internal organs and tissues or outside of the body.

- "Dictionary Definitions of Exsanguination". Reference.com. Archived from the original on 2007-07-11. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- "Blood Donation Information". UK National Blood Service. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- Roth, Elliot J. (2011). "Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage)". Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. New York, NY: Springer New York. p. 2423. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-79948-3_2201.

A subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is bleeding into the subarachnoid space that exists between the arachnoid and pia membranes that surround the brain.

- Liberty G, Hyman JH, Eldar-Geva T, Latinsky B, Gal M, Margalioth EJ (December 2008). "Ovarian hemorrhage after transvaginal ultrasonographically guided oocyte aspiration: a potentially catastrophic and not so rare complication among lean patients with polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertil. Steril. 93 (3): 874–879. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.028. PMID 19064264.

- Wang, Ye; An, Fei-Fei; Chan, Mark; Friedman, Beth; Rodriguez, Erik A; Tsien, Roger Y; Aras, Omer; Ting, Richard (2017-01-05). "18F-positron-emitting/fluorescent labeled erythrocytes allow imaging of internal hemorrhage in a murine intracranial hemorrhage model". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 37 (3): 776–786. doi:10.1177/0271678x16682510. PMC 5363488. PMID 28054494.

- Manning JE (2003-11-04). "Fluid and Blood Resuscitation". In Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS (eds.). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, Sixth edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-07-150091-3.

- Irita K (March 2011). "Risk and crisis management in intraoperative hemorrhage: Human factors in hemorrhagic critical events". Korean J Anesthesiol. 60 (3): 151–60. doi:10.4097/kjae.2011.60.3.151. PMC 3071477. PMID 21490815.

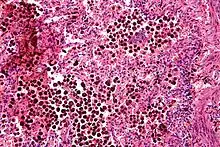

- Webert K, Cook RJ, Sigouin CS, Rebulla P, Heddle NM (November 2006). "The risk of bleeding in thrombocytopenic patients with acute myeloid leukemia". Haematologica. 91 (11): 1530–37. PMID 17043016.

- "Severe bleeding: First aid". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Scerbo, MH; Holcomb, JB; Taub, E; Gates, K; Love, JD; Wade, CE; Cotton, BA (December 2017). "The Trauma Center Is Too Late: Major Limb Trauma Without a Pre-hospital Tourniquet Has Increased Death From Hemorrhagic Shock". J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 83 (6): 1165–1172. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001666. PMID 29190257. S2CID 19121937.

- Hanigan, Sarah; Barnes, Geoffrey D. "Managing Anticoagulant-related Bleeding in Patients with Venous Thromboembolism". American College of Cardiology. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Nunez, TC; Cotton, BA (December 2009). "Transfusion Therapy in Hemorrhagic Shock". Curr Opin Crit Care. 15 (6): 536–41. doi:10.1097/MCC.0b013e328331575b. PMC 3139329. PMID 19730099.

- "Hemorrhage Origin". dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.