Arteriovenous malformation

Arteriovenous malformation is an abnormal connection between arteries and veins, bypassing the capillary system. This vascular anomaly is widely known because of its occurrence in the central nervous system (usually cerebral AVM), but can appear in any location. Although many AVMs are asymptomatic, they can cause intense pain or bleeding or lead to other serious medical problems.[1]

| Arteriovenous malformation | |

|---|---|

| Other names | AVM |

| |

| Micrograph of an arteriovenous malformation in the brain. HPS stain. | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery |

AVMs are usually congenital and belong to the RASopathies. The genetic transmission patterns of AVMs are incomplete, but there are known genetic mutations (for instance in the epithelial line, tumor suppressor PTEN gene) which can lead to an increased occurrence throughout the body.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of AVM vary according to the location of the malformation. Roughly 88%[2] of people with an AVM are asymptomatic; often the malformation is discovered as part of an autopsy or during treatment of an unrelated disorder (called in medicine an "incidental finding"); in rare cases, its expansion or a micro-bleed from an AVM in the brain can cause epilepsy, neurological deficit, or pain.[3]

The most general symptoms of a cerebral AVM include headaches and epileptic seizures, with more specific symptoms occurring that normally depend on the location of the malformation and the individual. Such possible symptoms include:[4]

- Difficulties with movement coordination, including muscle weakness and even paralysis;

- Vertigo (dizziness);

- Difficulties of speech (dysarthria) and communication, such as aphasia;

- Difficulties with everyday activities, such as apraxia;

- Abnormal sensations (numbness, tingling, or spontaneous pain);

- Memory and thought-related problems, such as confusion, dementia or hallucinations.

Cerebral AVMs may present themselves in a number of different ways:

- Bleeding (45% of cases)

- Acute onset of severe headache. May be described as the worst headache of the patient's life. Depending on the location of bleeding, may be associated with new fixed neurologic deficit. In unruptured brain AVMs, the risk of spontaneous bleeding may be as low as 1% per year. After a first rupture, the annual bleeding risk may increase to more than 5%.[5]

- Seizure or brain seizure (46%) Depending on the place of the AVM, it can cause loss of vision in one place.

- Headache (34%)

- Progressive neurologic deficit (21%)

- May be caused by mass effect or venous dilatations. Presence and nature of the deficit depend on location of lesion and the draining veins.[6]

- Pediatric patients

- Heart failure

- Macrocephaly

- Prominent scalp veins

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations are abnormal communications between the veins and arteries of the pulmonary circulation, leading to a right-to-left blood shunt.[7][8] They have no symptoms in up to 29% of all cases,[9] however they can give rise to serious complications including hemorrhage, and infection.[7] They are most commonly associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.[8]

Genetics

Can occur due to autosomal dominant diseases, such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.[10]

Pathophysiology

Arteries and veins are part of the vascular system. Arteries carry blood away from the heart to the lungs or the rest of the body, where the blood passes through capillaries, and veins return the blood to the heart. An AVM interferes with this process by forming a direct connection of the arteries and veins. AVMs can cause intense pain and lead to serious medical problems. Although AVMs are often associated with the brain and spinal cord, they can develop in other parts of the body.[11]

Normally, the arteries in the vascular system carry oxygen-rich blood, except in the case of the pulmonary artery. Structurally, arteries divide and sub-divide repeatedly, eventually forming a sponge-like capillary bed. Blood moves through the capillaries, giving up oxygen and taking up waste products, including CO

2, from the surrounding cells. Capillaries in turn successively join to form veins that carry blood away. The heart acts to pump blood through arteries and uptake the venous blood.

As an AVM lacks the dampening effect of capillaries on the blood flow, the AVM can get progressively larger over time as the amount of blood flowing through it increases, forcing the heart to work harder to keep up with the extra blood flow. It also causes the surrounding area to be deprived of the functions of the capillaries—removal of CO2 and delivery of nutrients to the cells. The resulting tangle of blood vessels, often called a nidus (Latin for "nest"), has no capillaries. It can be extremely fragile and prone to bleeding because of the abnormally direct connections between high-pressure arteries and low-pressure veins.[12] The resultant sign, audible via stethoscope, is a rhythmic, whooshing sound caused by excessively rapid blood flow through the arteries and veins. It has been given the term "bruit", French for noise. On some occasions, a patient with a brain AVM may become aware of the noise, which can compromise hearing and interfere with sleep in addition to causing psychological distress.

Diagnosis

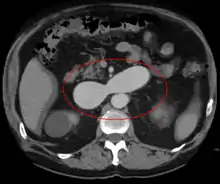

AVMs are diagnosed primarily by the following imaging methods:

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan is a noninvasive X-ray to view the anatomical structures within the brain to detect blood in or around the brain. A newer technology called CT angiography involves the injection of contrast into the blood stream to view the arteries of the brain. This type of test provides the best pictures of blood vessels through angiography and soft tissues through CT.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is a noninvasive test, which uses a magnetic field and radio-frequency waves to give a detailed view of the soft tissues of the brain.

- Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) – scans created using magnetic resonance imaging to specifically image the blood vessels and structures of the brain. A magnetic resonance angiogram can be an invasive procedure, involving the introduction of contrast dyes (e.g., gadolinium MR contrast agents) into the vasculature of a patient using a catheter inserted into an artery and passed through the blood vessels to the brain. Once the catheter is in place, the contrast dye is injected into the bloodstream and the MR images are taken. Additionally or alternatively, flow-dependent or other contrast-free magnetic resonance imaging techniques can be used to determine the location and other properties of the vasculature.

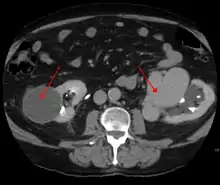

AVMs can occur in various parts of the body:

- brain (cerebral AV malformation)

- spleen[13]

- lung[14][15]

- kidney[16]

- spinal cord[17]

- liver[18]

- intercostal space[19]

- iris[20]

- spermatic cord[21]

- extremities – arm, shoulder, etc.

AVMs may occur in isolation or as a part of another disease (for example, Von Hippel–Lindau disease or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia).

AVMs have been shown to be associated with aortic stenosis.[22]

Bleeding from an AVM can be relatively mild or devastating. It can cause severe and less often fatal strokes. If a cerebral AVM is detected before a stroke occurs, usually the arteries feeding blood into the nidus can be closed off to avert the danger. However, interventional therapy may also be relatively risky.

Treatment

Treatment for brain AVMs can be symptomatic, and patients should be followed by a neurologist for any seizures, headaches, or focal neurologic deficits. AVM-specific treatment may also involve endovascular embolization, neurosurgery or radiosurgery.[4] Embolization, that is, cutting off the blood supply to the AVM with coils, particles, acrylates, or polymers introduced by a radiographically guided catheter, may be used in addition to neurosurgery or radiosurgery, but is rarely successful in isolation except in smaller AVMs.[23] Gamma knife may also be used.[24]

Treatment of lung AVMs is typically performed with endovascular embolization alone, which is considered the standard of care.[15]

Epidemiology

The estimated detection rate of AVM in the US general population is 1.4/100,000 per year.[25] This is approximately one fifth to one seventh the incidence of intracranial aneurysms. An estimated 300,000 Americans have AVMs, of whom 12% (approximately 36,000) will exhibit symptoms of greatly varying severity.[4]

History

Luschka (1820–1875) and Virchow (1821–1902) first described arteriovenous malformations in the mid-1800s. Olivecrona (1891–1980) performed the first surgical excision of an intracranial AVM in 1932.

Society and culture

Notable cases

- Indonesian actress Egidia Savitri died from complications of AVM on November 29, 2013.[26]

- Phoenix Suns point guard AJ Price nearly died from AVM in 2004 while a student at the University of Connecticut.

- On December 13, 2006, Senator Tim Johnson of South Dakota was diagnosed with AVM and treated at George Washington University Hospital.[27]

- On August 3, 2011, Mike Patterson of the Philadelphia Eagles collapsed on the field and had a seizure during a practice, leading to him being diagnosed with AVM.[28]

- Actor Ricardo Montalbán was born with spinal AVM.[29] During the filming of the 1951 film Across the Wide Missouri, Montalbán was thrown from his horse, knocked unconscious, and trampled by another horse which aggravated his AVM and resulted in a painful back injury that never healed. The pain increased as he aged, and in 1993, Montalbán underwent 9+1⁄2 hours of spinal surgery which left him paralyzed below the waist and using a wheelchair.[30]

- Actor/comedian T. J. Miller was diagnosed with AVM after filming Yogi Bear in New Zealand in 2010; Miller described his experience with the disease on the Pete Holmes podcast You Made It Weird on October 28, 2011, shedding his comedian side for a moment and becoming more philosophical, narrating his behaviors and inability to sleep during that time. He had a seizure upon return to Los Angeles and successfully underwent surgery that had a mortality rate of ten percent.[31]

- Jazz guitarist Pat Martino experienced an AVM and subsequently developed amnesia and manic depression. He eventually re-learned to play the guitar by listening to his own recordings from before the aneurysm.[32]

- YouTube vlogger Nikki Lilly (Nikki Christou), winner of the 2016 season of Junior Bake Off was born with AVM, which has resulted in some facial disfigurement.[33]

- Composer and lyricist William Finn was diagnosed with AVM and underwent Gamma Knife surgery in September 1992, soon after he won the 1992 Tony Award for best musical, awarded to "Falsettos".[34] Finn wrote the 1998 Off-Broadway musical A New Brain about the experience.

- Former Florida Gators and Oakland Raiders linebacker Neiron Ball was diagnosed with AVM in 2011 while playing for Florida, but recovered and was cleared to play. On September 16, 2018, Ball was placed in a medically induced coma due to complications of the disease, which lasted until his death on September 10, 2019.[35]

- Country music singer Drake White was diagnosed with AVM in January 2019, and is undergoing treatment.

Cultural Depictions

- In the HBO series Six Feet Under (TV series), main character Nate Fisher discovers he has an AVM after being in a car accident and getting a precautionary cat scan at the hospital during Season 1. His AVM becomes a key focus during Season 2 and again in Season 5.

Research

Despite many years of research, the central question of whether to treat AVMs has not been answered. All treatments, whether involving surgery, radiation, or drugs, have risks and side-effects. Therefore, it might be better in some cases to avoid treatment altogether and simply accept a small risk of coming to harm from the AVM itself. This question is currently being addressed in clinical trials.[36]

See also

- Foix–Alajouanine syndrome

- Haemangioma

- Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome

- Parkes Weber syndrome

References

- "Arteriovenous Malformations and Other Vascular Lesions of the Central Nervous System Fact Sheet | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- "National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". nih.gov. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "Arteriovenous Malformations". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Arteriovenous Malformation Information Page at NINDS

- Stapf, C.; Mast, H.; Sciacca, R. R.; Choi, J. H.; Khaw, A. V.; Connolly, E. S.; Pile-Spellman, J.; Mohr, J. P. (2006). "Predictors of hemorrhage in patients with untreated brain arteriovenous malformation". Neurology. 66 (9): 1350–5. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000210524.68507.87. PMID 16682666. S2CID 22004276.

- Choi, J.H.; Mast, H.; Hartmann, A.; Marshall, R.S.; Pile-Spellman, J.; Mohr, J.P.; Stapf, C. (2009). "Clinical and morphological determinants of focal neurological deficits in patients with unruptured brain arteriovenous malformation". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 287 (1–2): 126–30. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.011. PMC 2783734. PMID 19729171.

- Reichert, M; Kerber, S; Alkoudmani, I; Bodner, J (April 2016). "Management of a solitary pulmonary arteriovenous malformation by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and anatomic lingula resection: video and review". Surgical Endoscopy. 30 (4): 1667–9. doi:10.1007/s00464-015-4337-0. PMID 26156615. S2CID 22394114.

- Tellapuri, S; Park, HS; Kalva, SP (August 2019). "Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations". The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 35 (8): 1421–1428. doi:10.1007/s10554-018-1479-x. PMID 30386957. S2CID 53144651.

- Goodenberger DM (2008). "Chapter 84 Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations". Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1470. ISBN 978-0-07-145739-2.

- "Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- Schimmel, Katharina; Ali, Md Khadem; Tan, Serena Y.; Teng, Joyce; Do, Huy M.; Steinberg, Gary K.; Stevenson, David A.; Spiekerkoetter, Edda (2021-08-21). "Arteriovenous Malformations—Current Understanding of the Pathogenesis with Implications for Treatment". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (16): 9037. doi:10.3390/ijms22169037. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8396465. PMID 34445743.

- Mouchtouris, Nikolaos; Jabbour, Pascal M.; Starke, Robert M.; Hasan, David M.; Zanaty, Mario; Theofanis, Thana; Ding, Dale; Tjoumakaris, Stavropoula I.; Dumont, Aaron S.; Ghobrial, George M.; Kung, David (February 2015). "Biology of cerebral arteriovenous malformations with a focus on inflammation". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 35 (2): 167–175. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2014.179. PMC 4426734. PMID 25407267.

- Agrawal, Aditya; Whitehouse, Richard; Johnson, Robert W.; Augustine, Titus (2006). "Giant splenic artery aneurysm associated with arteriovenous malformation". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 44 (6): 1345–9. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.06.049. PMID 17145440.

- Chowdhury, Ujjwal K.; Kothari, Shyam S.; Bishnoi, Arvind K.; Gupta, Ruchika; Mittal, Chander M.; Reddy, Srikrishna (2009). "Successful Lobectomy for Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformation Causing Recurrent Massive Haemoptysis". Heart, Lung and Circulation. 18 (2): 135–9. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2007.11.142. PMID 18294908.

- Cusumano, Lucas R.; Duckwiler, Gary R.; Roberts, Dustin G.; McWilliams, Justin P. (2019-08-30). "Treatment of Recurrent Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations: Comparison of Proximal Versus Distal Embolization Technique". CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology. 43 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1007/s00270-019-02328-0. ISSN 1432-086X. PMID 31471718. S2CID 201675132.

- Barley, Fay L.; Kessel, David; Nicholson, Tony; Robertson, Iain (2006). "Selective Embolization of Large Symptomatic Iatrogenic Renal Transplant Arteriovenous Fistula". CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology. 29 (6): 1084–7. doi:10.1007/s00270-005-0265-z. PMID 16794894. S2CID 9335750.

- Kishi, K; Shirai, S; Sonomura, T; Sato, M (2005). "Selective conformal radiotherapy for arteriovenous malformation involving the spinal cord". The British Journal of Radiology. 78 (927): 252–4. doi:10.1259/bjr/50653404. PMID 15730991.

- Bauer, Tilman; Britton, Peter; Lomas, David; Wight, Derek G.D.; Friend, Peter J.; Alexander, Graeme J.M. (1995). "Liver transplantation for hepatic arteriovenous malformation in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia". Journal of Hepatology. 22 (5): 586–90. doi:10.1016/0168-8278(95)80455-2. PMID 7650340.

- Rivera, Peter P.; Kole, Max K.; Pelz, David M.; Gulka, Irene B.; McKenzie, F. Neil; Lownie, Stephen P. (2006). "Congenital Intercostal Arteriovenous Malformation". American Journal of Roentgenology. 187 (5): W503–6. doi:10.2214/AJR.05.0367. PMID 17056881.

- Shields, Jerry A.; Streicher, Theodor F. E.; Spirkova, Jane H. J.; Stubna, Michal; Shields, Carol L. (2006). "Arteriovenous Malformation of the Iris in 14 Cases". Archives of Ophthalmology. 124 (3): 370–5. doi:10.1001/archopht.124.3.370. PMID 16534057.

- Sountoulides, Petros; Bantis, Athanasios; Asouhidou, Irene; Aggelonidou, Hellen (2007). "Arteriovenous malformation of the spermatic cord as the cause of acute scrotal pain: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 1: 110. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-1-110. PMC 2194703. PMID 17939869.

- Batur, Pelin; Stewart, William J.; Isaacson, J. Harry (2003). "Increased Prevalence of Aortic Stenosis in Patients With Arteriovenous Malformations of the Gastrointestinal Tract in Heyde Syndrome". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (15): 1821–4. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.15.1821. PMID 12912718.

- Jafar, Jafar J.; Davis, Adam J.; Berenstein, Alejandro; Choi, In Sup; Kupersmith, Mark J. (1993-01-01). "The effect of embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate prior to surgical resection of cerebral arteriovenous malformations". Journal of Neurosurgery. 78 (1): 60–69. doi:10.3171/jns.1993.78.1.0060. ISSN 0022-3085. PMID 8416244.

- "Conditions We Treat". Macquarie University Hospital. Archived from the original on 2013-06-13.

- Stapf, C.; Mast, H.; Sciacca, R.R.; Berenstein, A.; Nelson, P.K.; Gobin, Y.P.; Pile-Spellman, J.; Mohr, J.P. (2003). "The New York Islands AVM Study: Design, Study Progress, and Initial Results". Stroke. 34 (5): e29–33. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000068784.36838.19. PMID 12690217.

- Suhendra, Ichsan. "Pesinetron Egidia Savitri Telah Pergi". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Kompas Cyber Media. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Sen. Johnson recovering after brain surgery". AP. December 14, 2006.

- "Mike Patterson's Collapse Reportedly Related To Brain AVM". sbnation.com. 2011-08-04. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "Ricardo Montalban tribute" YouTube, acceptance speech video of Easter Seals Lifetime Achievement Award

- "Inside". mahalo.com. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Pete Holmes (October 27, 2011). "You Made It Weird with Pete Holmes". You Made It Weird #2: TJ Miller (Podcast). Nerdist Industries. Event occurs at 37:45. Archived from the original on February 12, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- Vida, Vendela. Confidence, or the Appearance of Confidence: The Best of the Believer Music Interviews. No ed. San Francisco, Calif.: Believer, a Tiny Division of McSweeney's Which Is Also Tiny, 2014. Print.

- "Junior Bake Off 2016 Winner announced". BBC Media Centre. BBC Online. 25 November 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Pall, Ellen (14 June 1998). "The Long-Running Musical of William Finn's Life". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "Neiron Ball, former Raiders LB, in medically induced coma after aneurysm". ESPN. September 26, 2018.

- Research trials in arterio-venous malformations; Rustam Al-Shahi Salman Archived February 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine