Arctic fox

The Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), also known as the white fox, polar fox, or snow fox, is a small fox native to the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere and common throughout the Arctic tundra biome.[1][7][8] It is well adapted to living in cold environments, and is best known for its thick, warm fur that is also used as camouflage. It has a large and very fluffy tail. In the wild, most individuals do not live past their first year but some exceptional ones survive up to 11 years.[9] Its body length ranges from 46 to 68 cm (18 to 27 in), with a generally rounded body shape to minimize the escape of body heat.

| Arctic fox | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Vulpes |

| Species: | V. lagopus |

| Binomial name | |

| Vulpes lagopus | |

| |

| Arctic fox range | |

| Synonyms[3][4][5][6] | |

|

List

| |

The Arctic fox preys on many small creatures such as lemmings, voles, ringed seal pups, fish, waterfowl, and seabirds. It also eats carrion, berries, seaweed, and insects and other small invertebrates. Arctic foxes form monogamous pairs during the breeding season and they stay together to raise their young in complex underground dens. Occasionally, other family members may assist in raising their young. Natural predators of the Arctic fox are golden eagles,[10] Arctic wolves, polar bears,[11] wolverines, red foxes, and grizzly bears.[12][13]

Behavior

Arctic foxes must endure a temperature difference of up to 90–100 °C (160–180 °F) between the external environment and their internal core temperature.[14] To prevent heat loss, the Arctic fox curls up tightly tucking its legs and head under its body and behind its furry tail. This position gives the fox the smallest surface area to volume ratio and protects the least insulated areas. Arctic foxes also stay warm by getting out of the wind and residing in their dens.[15][14] Although the Arctic foxes are active year-round and do not hibernate, they attempt to preserve fat by reducing their locomotor activity.[15][16] They build up their fat reserves in the autumn, sometimes increasing their body weight by more than 50%. This provides greater insulation during the winter and a source of energy when food is scarce.[17]

Reproduction

In the spring, the Arctic fox's attention switches to reproduction and a home for their potential offspring. They live in large dens in frost-free, slightly raised ground. These are complex systems of tunnels covering as much as 1,000 m2 (11,000 sq ft) and are often in eskers, long ridges of sedimentary material deposited in formerly glaciated regions. These dens may be in existence for many decades and are used by many generations of foxes.[17]

Arctic foxes tend to select dens that are easily accessible with many entrances, and that are clear from snow and ice making it easier to burrow in. The Arctic fox builds and chooses dens that face southward towards the sun, which makes the den warmer. Arctic foxes prefer large, maze-like dens for predator evasion and a quick escape especially when red foxes are in the area. Natal dens are typically found in rugged terrain, which may provide more protection for the pups. But, the parents will also relocate litters to nearby dens to avoid predators. When red foxes are not in the region, Arctic foxes will use dens that the red fox previously occupied. Shelter quality is more important to the Arctic fox than the proximity of spring prey to a den.[12]

The main prey in the tundra are lemmings, which is why the white fox is often called the "lemming fox". The white fox's reproduction rates reflect the lemming population density, which cyclically fluctuates every 3–5 years.[9][13] When lemmings are abundant, the white fox can give birth to 18 pups, but they often do not reproduce when food is scarce. The "coastal fox" or blue fox lives in an environment where food availability is relatively consistent, and they will have up to 5 pups every year.[13]

Breeding usually takes place in April and May, and the gestation period is about 52 days. Litters may contain as many as 25 (the largest litter size in the order Carnivora).[18] The young emerge from the den when 3 to 4 weeks old and are weaned by 9 weeks of age.[17]

Arctic foxes are primarily monogamous and both parents will care for the offspring. When predators and prey are abundant, Arctic foxes are more likely to be promiscuous (exhibited in both males and females) and display more complex social structures. Larger packs of foxes consisting of breeding or non-breeding males or females can guard a single territory more proficiently to increase pup survival. When resources are scarce, competition increases and the number of foxes in a territory decreases. On the coasts of Svalbard, the frequency of complex social structures is larger than inland foxes that remain monogamous due to food availability. In Scandinavia, there are more complex social structures compared to other populations due to the presence of the red fox. Also, conservationists are supplying the declining population with supplemental food. One unique case, however, is Iceland where monogamy is the most prevalent. The older offspring (1-year-olds) often remain within their parent's territory even though predators are absent and there are fewer resources, which may indicate kin selection in the fox.[13]

Diet

Arctic foxes generally eat any small animal they can find, including lemmings, voles, other rodents, hares, birds, eggs, fish, and carrion. They scavenge on carcasses left by larger predators such as wolves and polar bears, and in times of scarcity also eat their feces. In areas where they are present, lemmings are their most common prey,[17] and a family of foxes can eat dozens of lemmings each day. In some locations in northern Canada, a high seasonal abundance of migrating birds that breed in the area may provide an important food source. On the coast of Iceland and other islands, their diet consists predominantly of birds. During April and May, the Arctic fox also preys on ringed seal pups when the young animals are confined to a snow den and are relatively helpless. They also consume berries and seaweed, so they may be considered omnivores.[19] This fox is a significant bird-egg predator, consuming eggs of all except the largest tundra bird species.[20] When food is overabundant, the Arctic fox buries (caches) the surplus as a reserve.

Arctic foxes survive harsh winters and food scarcity by either hoarding food or storing body fat. Fat is deposited subcutaneously and viscerally in Arctic foxes. At the beginning of winter, the foxes have approximately 14740 kJ of energy storage from fat alone. Using the lowest BMR value measured in Arctic foxes, an average sized fox (3.5 kg (7.7 lb)) would need 471 kJ/day during the winter to survive. Arctic foxes can acquire goose eggs (from greater snow geese in Canada) at a rate of 2.7–7.3 eggs/h, and they store 80–97% of them. Scats provide evidence that they eat the eggs during the winter after caching. Isotope analysis shows that eggs can still be eaten after a year, and the metabolizable energy of a stored goose egg only decreases by 11% after 60 days (a fresh egg has about 816 kJ). Researchers have also noted that some eggs stored in the summer are accessed later the following spring prior to reproduction.[21]

Adaptations

The Arctic fox lives in some of the most frigid extremes on the planet, but they do not start to shiver until the temperature drops to −70 °C (−94 °F). Among its adaptations for survival in the cold is its dense, multilayered pelage, which provides excellent insulation.[22][23] Additionally, the Arctic fox is the only canid whose foot pads are covered in fur. There are two genetically distinct coat color morphs: white and blue.[15] The white morph has seasonal camouflage, white in winter and brown along the back with light grey around the abdomen in summer. The blue morph is often a dark blue, brown, or grey color year-round. Although the blue allele is dominant over the white allele, 99% of the Arctic fox population is the white morph.[13][9] Two similar mutations to MC1R cause the blue color and the lack of seasonal color change.[24] The fur of the Arctic fox provides the best insulation of any mammal.[25]

The fox has a low surface area to volume ratio, as evidenced by its generally compact body shape, short muzzle and legs, and short, thick ears. Since less of its surface area is exposed to the Arctic cold, less heat escapes from its body.[26]

Sensory modalities

The Arctic fox has a functional hearing range between 125 Hz–16 kHz with a sensitivity that is ≤ 60 dB in air, and an average peak sensitivity of 24 dB at 4 kHz. Overall, the Arctic foxes hearing is less sensitive than the dog and the kit fox. The Arctic fox and the kit fox have a low upper-frequency limit compared to the domestic dog and other carnivores.[27] The Arctic fox can easily hear lemmings burrowing under 4-5 inches of snow.[28] When it has located its prey, it pounces and punches through the snow to catch its prey.[26]

The Arctic fox also has a keen sense of smell. They can smell carcasses that are often left by polar bears anywhere from 10 to 40 km (6.2 to 24.9 mi). It is possible that they use their sense of smell to also track down polar bears. Additionally, Arctic foxes can smell and find frozen lemmings under 46–77 cm (18–30 in) of snow, and can detect a subnivean seal lair under 150 cm (59 in) of snow.[29]

Physiology

The Arctic fox contains advantageous genes to overcome extreme cold and starvation periods. Transcriptome sequencing has identified two genes that are under positive selection: Glycolipid transfer protein domain containing 1 (GLTPD1) and V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 2 (AKT2). GLTPD1 is involved in the fatty acid metabolism, while AKT2 pertains to the glucose metabolism and insulin signaling.[30]

The average mass specific BMR and total BMR are 37% and 27% lower in the winter than the summer. The Arctic fox decreases its BMR via metabolic depression in the winter to conserve fat storage and minimize energy requirements. According to the most recent data, the lower critical temperature of the Arctic fox is at −7 °C (19 °F) in the winter and 5 °C (41 °F) in the summer. It was commonly believed that the Arctic fox had a lower critical temperature below −40 °C (−40 °F). However, some scientists have concluded that this statistic is not accurate since it was never tested using the proper equipment.[14]

About 22% of the total body surface area of the Arctic fox dissipates heat readily compared to red foxes at 33%. The regions that have the greatest heat loss are the nose, ears, legs, and feet, which is useful in the summer for thermal heat regulation. Also, the Arctic fox has a beneficial mechanism in their nose for evaporative cooling like dogs, which keeps the brain cool during the summer and exercise.[16] The thermal conductivity of Arctic fox fur in the summer and winter is the same; however, the thermal conductance of the Arctic fox in the winter is lower than the summer since fur thickness increases by 140%. In the summer, the thermal conductance of the Arctic foxes body is 114% higher than the winter, but their body core temperature is constant year-round.

One way that Arctic foxes regulate their body temperature is by utilizing a countercurrent heat exchange in the blood of their legs.[14] Arctic foxes can constantly keep their feet above the tissue freezing point (−1 °C (30 °F)) when standing on cold substrates without losing mobility or feeling pain. They do this by increasing vasodilation and blood flow to a capillary rete in the pad surface, which is in direct contact with the snow rather than the entire foot. They selectively vasoconstrict blood vessels in the center of the foot pad, which conserves energy and minimizes heat loss.[16][31] Arctic foxes maintain the temperature in their paws independently from the core temperature. If the core temperature drops, the pad of the foot will remain constantly above the tissue freezing point.[31]

Size

The average head-and-body length of the male is 55 cm (22 in), with a range of 46 to 68 cm (18 to 27 in), while the female averages 52 cm (20 in) with a range of 41 to 55 cm (16 to 22 in).[22][32] In some regions, no difference in size is seen between males and females. The tail is about 30 cm (12 in) long in both sexes. The height at the shoulder is 25 to 30 cm (9.8 to 11.8 in).[33] On average males weigh 3.5 kg (7.7 lb), with a range of 3.2 to 9.4 kg (7.1 to 20.7 lb), while females average 2.9 kg (6.4 lb), with a range of 1.4 to 3.2 kg (3.1 to 7.1 lb).[22]

Taxonomy

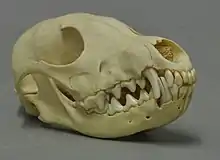

Vulpes lagopus is a 'true fox' belonging to the genus Vulpes of the fox tribe Vulpini, which consists of 12 extant species.[30] It is classified under the subfamily Caninae of the canid family Canidae. Although it has previously been assigned to its own monotypic genus Alopex, recent genetic evidence now places it in the genus Vulpes along with the majority of other foxes.[7][34]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

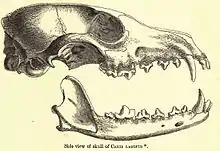

It was originally described by Carl Linnaeus in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae in 1758 as Canis lagopus. The type specimen was recovered from Lapland, Sweden. The generic name vulpes is Latin for "fox".[37] The specific name lagopus is derived from Ancient Greek λαγώς (lagōs, "hare") and πούς (pous, "foot"), referring to the hair on its feet similar to those found in cold-climate species of hares.[36]

Looking at the most recent phylogeny, the Arctic fox and the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) diverged approximately 3.17MYA. Additionally, the Arctic fox diverged from its sister group, the kit fox (Vulpes macrotis), at about 0.9MYA.[30]

Origins

The origins of the Arctic fox have been described by the "out of Tibet" hypothesis. On the Tibetan Plateau, fossils of the extinct ancestral Arctic fox (Vulpes qiuzhudingi) from the early Pliocene (5.08–3.6 MYA) were found along with many other precursors of modern mammals that evolved during the Pliocene (5.3–2.6 MYA). It is believed that this ancient fox is the ancestor of the modern Arctic fox. Globally, the Pliocene was about 2–3 °C warmer than today, and the Arctic during the summer in the mid-Pliocene was 8 °C warmer. By using stable carbon and oxygen isotope analysis of fossils, researchers claim that the Tibetan Plateau experienced tundra-like conditions during the Pliocene and harbored cold-adapted mammals that later spread to North America and Eurasia during the Pleistocene Epoch (2.6 million-11,700 years ago).[38]

Subspecies

Besides the nominate subspecies, the common Arctic fox, V. l. lagopus, four other subspecies of this fox have been described:

- Bering Islands Arctic fox, V. l. beringensis

- Greenland Arctic fox, V. l. foragoapusis

- Iceland Arctic fox, V. l. fuliginosus

- Pribilof Islands Arctic fox, V. l. pribilofensis

Distribution and habitat

The Arctic fox has a circumpolar distribution and occurs in Arctic tundra habitats in northern Europe, northern Asia, and North America. Its range includes Greenland, Iceland, Fennoscandia, Svalbard, Jan Mayen (where it was hunted to extinction)[39] and other islands in the Barents Sea, northern Russia, islands in the Bering Sea, Alaska, and Canada as far south as Hudson Bay. In the late 19th century, it was introduced into the Aleutian Islands southwest of Alaska. However, the population on the Aleutian Islands is currently being eradicated in conservation efforts to preserve the local bird population.[1] It mostly inhabits tundra and pack ice, but is also present in Canadian boreal forests (northeastern Alberta, northern Saskatchewan, northern Manitoba, Northern Ontario, Northern Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador)[40] and the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska. They are found at elevations up to 3,000 m (9,800 ft) above sea level and have been seen on sea ice close to the North Pole.[41]

The Arctic fox is the only land mammal native to Iceland.[42] It came to the isolated North Atlantic island at the end of the last ice age, walking over the frozen sea. The Arctic Fox Center in Súðavík contains an exhibition on the Arctic fox and conducts studies on the influence of tourism on the population.[43] Its range during the last ice age was much more extensive than it is now, and fossil remains of the Arctic fox have been found over much of northern Europe and Siberia.[1]

The color of the fox's coat also determines where they are most likely to be found. The white morph mainly lives inland and blends in with the snowy tundra, while the blue morph occupies the coasts because its dark color blends in with the cliffs and rocks.[9]

Arctic fox in winter pelage, Iceland

Arctic fox in winter pelage, Iceland Arctic fox

Arctic fox

Migrations and travel

During the winter, 95.5% of Arctic foxes utilize commuting trips, which remain within the fox's home range. Commuting trips in Arctic foxes last less than 3 days and occur between 0–2.9 times a month. Nomadism is found in 3.4% of the foxes, and loop migrations (where the fox travels to a new range, then returns to its home range) are the least common at 1.1%. Arctic foxes in Canada that undergo nomadism and migrations voyage from the Canadian archipelago to Greenland and northwestern Canada. The duration and distance traveled between males and females is not significantly different.

Arctic foxes closer to goose colonies (located at the coasts) are less likely to migrate. Meanwhile, foxes experiencing low-density lemming populations are more likely to make sea ice trips. Residency is common in the Arctic fox population so that they can maintain their territories. Migratory foxes have a mortality rate >3 times higher than resident foxes. Nomadic behavior becomes more common as the foxes age.[44]

In July 2019, the Norwegian Polar Institute reported the story of a yearling female which was fitted with a GPS tracking device and then released by their researchers on the east coast of Spitsbergen in the Svalbard group of islands.[45] The young fox crossed the polar ice from the islands to Greenland in 21 days, a distance of 1,512 km (940 mi). She then moved on to Ellesmere Island in northern Canada, covering a total recorded distance of 3,506 km (2,179 mi) in 76 days, before her GPS tracker stopped working. She averaged just over 46 km (29 mi) a day, and managed as much as 155 km (96 mi) in a single day.[46]

Conservation status

The Arctic fox has been assessed as least concern on the IUCN Red List since 2004.[1] However, the Scandinavian mainland population is acutely endangered, despite being legally protected from hunting and persecution for several decades. The estimate of the adult population in all of Norway, Sweden, and Finland is fewer than 200 individuals.[17] Of these, especially in Finland, the Arctic fox is even classified as critically endangered,[47] because even though the animal was pacified in Finland since 1940, the population has not recovered despite that.[48] As a result, the populations of Arctic fox have been carefully studied and inventoried in places such as the Vindelfjällens Nature Reserve (Sweden), which has the Arctic fox as its symbol.

The abundance of the Arctic fox tends to fluctuate in a cycle along with the population of lemmings and voles (a 3- to 4-year cycle).[20] The populations are especially vulnerable during the years when the prey population crashes, and uncontrolled trapping has almost eradicated two subpopulations.[17]

The pelts of Arctic foxes with a slate-blue coloration were especially valuable. They were transported to various previously fox-free Aleutian Islands during the 1920s. The program was successful in terms of increasing the population of blue foxes, but their predation of Aleutian Canada geese conflicted with the goal of preserving that species.[49]

The Arctic fox is losing ground to the larger red fox. This has been attributed to climate change—the camouflage value of its lighter coat decreases with less snow cover.[50] Red foxes dominate where their ranges begin to overlap by killing Arctic foxes and their kits.[51] An alternative explanation of the red fox's gains involves the gray wolf. Historically, it has kept red fox numbers down, but as the wolf has been hunted to near extinction in much of its former range, the red fox population has grown larger, and it has taken over the niche of top predator. In areas of northern Europe, programs are in place that allow the hunting of red foxes in the Arctic fox's previous range.

As with many other game species, the best sources of historical and large-scale population data are hunting bag records and questionnaires. Several potential sources of error occur in such data collections.[52] In addition, numbers vary widely between years due to the large population fluctuations. However, the total population of the Arctic fox must be in the order of several hundred thousand animals.[53]

The world population of Arctic foxes is thus not endangered, but two Arctic fox subpopulations are. One is on Medny Island (Commander Islands, Russia), which was reduced by some 85–90%, to around 90 animals, as a result of mange caused by an ear tick introduced by dogs in the 1970s.[54] The population is currently under treatment with antiparasitic drugs, but the result is still uncertain.

The other threatened population is the one in Fennoscandia (Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Kola Peninsula). This population decreased drastically around the start of the 20th century as a result of extreme fur prices, which caused severe hunting also during population lows.[55] The population has remained at a low density for more than 90 years, with additional reductions during the last decade.[56] The total population estimate for 1997 is around 60 adults in Sweden, 11 adults in Finland, and 50 in Norway. From Kola, there are indications of a similar situation, suggesting a population of around 20 adults. The Fennoscandian population thus numbers around 140 breeding adults. Even after local lemming peaks, the Arctic fox population tends to collapse back to levels dangerously close to nonviability.[53]

The Arctic fox is classed as a "prohibited new organism" under New Zealand's Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996, preventing it from being imported into the country.[57]

See also

- Arctic rabies virus

References

- Angerbjörn, A. & Tannerfeldt, M. (2014). "Vulpes lagopus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T899A57549321. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-2.RLTS.T899A57549321.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Linnæus, C. (1758). "Vulpes lagopus". Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiæ (Stockholm): Laurentius Salvius. p. 40. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- Oken, L. (1816). Lehrbuch der Naturgeschichte. Vol. 3. Jena, Germany: August Schmid und Comp. p. 1033.

- Merriam, C.H. (1900). "Papers from the Harriman Alaska Expedition. I. Descriptions of twenty-six new mammals from Alaska and British North America". Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Sciences. 2: 15–16. JSTOR 24525852. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018.

- Merriam, C.H. (1902). "Four New Arctic Foxes". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 15: 171. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018.

- Merriam 1902, pp. 171–172.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "Arctic Fox | National Geographic". Animals. 10 September 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- Pagh, S. & Hersteinsson, P. (2008). "Difference in diet and age structure of blue and white Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) in the Disko Bay area, West Greenland". Polar Research. 27 (1): 44–51. Bibcode:2008PolRe..27...44P. doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.2008.00042.x. S2CID 129105385.

- Arctic Fox at Fisheries and Land Resources

- Arctic Fox at National Geographic

- Gallant, D.; Reid, D.G.; Slough, B.G.; Berteaux, D. (2014). "Natal den selection by sympatric arctic and red foxes on Herschel Island, Yukon, Canada". Polar Biology. 37 (3): 333–345. doi:10.1007/s00300-013-1434-1. S2CID 18744412.

- Noren, K.; Hersteinsson, P.; Samelius, G.; Eide, N.E.; Fuglei, E.; Elmhagen, B.; Dalén, L.; Meijer, T. & Angerbjörn, A. (2012). "From monogamy to complexity: social organization of arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) in contrasting ecosystems". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 90 (9): 1102–1116. doi:10.1139/z2012-077.

- Fuglesteg, B.; Haga, Ø.E.; Folkow, L.P.; Fuglei, E. & Blix, A.S. (2006). "Seasonal variations in basal metabolic rate, lower critical temperature and responses to temporary starvation in the arctic fox (Alopex lagopus) from Svalbard". Polar Biology. 29 (4): 308–319. doi:10.1007/s00300-005-0054-9. S2CID 31158070.

- Prestrud, P. (1991). "Adaptations by the Arctic Fox (Alopex lagopus) to the Polar Winter". Arctic. 44 (2): 132–138. doi:10.14430/arctic1529. JSTOR 40511073. S2CID 45830118.

- Klir, J. & Heath, J. (1991). "An Infrared Thermographic Study of Surface Temperature in Relation to External Thermal Stress in Three Species of Foxes: The Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes), Arctic Fox (Alopex lagopus), and Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis)". Physiological Zoology. 65 (5): 1011–1021. doi:10.1086/physzool.65.5.30158555. JSTOR 30158555. S2CID 87183522.

- Angerbjörn, A.; Berteaux, D.; I.R. (2012). "Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus)". Arctic report card: Update for 2012. NOAA Arctic Research Program. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- MacDonald, David W. (2004). Biology and Conservation of Wild Canids. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-851556-2.

- Bockstoce, J.R. (2009). Furs and frontiers in the far north: the contest among native and foreign nations for the Bering Strait fur trade. Yale University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-300-14921-0.

- Truett, J.C.; Johnson, S.R. (2000). The natural history of an Arctic oil field: development and the biota. Academic Press. pp. 160–163. ISBN 978-0-12-701235-3.

- Careau, V.; Giroux, J.F.; Gauthier, G. & Berteaux, D. (2008). "Surviving on cached foods — the energetics of egg-caching by Arctic foxes". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 86 (10): 1217–1223. doi:10.1139/Z08-102. S2CID 51683546.

- Alopex lagopus at the Smithsonian Archived 13 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, Michael Hoffmann and David W. Macdonald (eds.) (2004). Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group.

- Våge, D.I.; Fuglei, E.; Snipstad, K.; Beheim, J.; Landsem, V.M.; Klungland, H. (2005). "Two cysteine substitutions in the MC1R generate the blue variant of the arctic fox (Alopex lagopus) and prevent expression of the white winter coat". Peptides. 26 (10): 1814–1817. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2004.11.040. hdl:11250/174384. PMID 15982782. S2CID 7264542.

- "Adaptations by the arctic fox to the polar winter" (PDF). Arctic, vol.44 no.2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- Arctic Fox Alopex lagopus Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Department of Environment and Conservation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Stansbury, A.; Thomas, J.A.; Stalf, C.E.; Murphy, L.D.; Lombardi, D.; Carpenter, J. & Mueller, T. (2014). "Behavioral audiogram of two Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus)". Polar Biology. 37 (3): 417–422. doi:10.1007/s00300-014-1446-5. S2CID 17154503.

- Perry, Richard (1973). The Polar Worlds (First ed.). New York, New York: Taplinger Pub. Co., Inc. p. 188. ISBN 978-0800864057.

- Lai, S.; Bety, J. & Berteaux, D. (2015). "Spatio–temporal hotspots of satellite– tracked arctic foxes reveal a large detection range in a mammalian predator". Movement Ecology. 3 (37): 37. doi:10.1186/s40462-015-0065-2. PMC 4644628. PMID 26568827.

- Kumar, V.; Kutschera, V.E.; Nilsson, M.A. & Janke, A. (2015). "Genetic signatures of adaptation revealed from transcriptome sequencing of Arctic and red foxes". BMC Genomics. 16: 585. doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1724-9. PMC 4528681. PMID 26250829.

- Henshaw, R.; Underwood, L.; Casey, T. (1972). "Peripheral Thermoregulation: Foot Temperature in Two Arctic Canines". Science. 175 (4025): 988–990. Bibcode:1972Sci...175..988H. doi:10.1126/science.175.4025.988. JSTOR 1732725. PMID 5009400. S2CID 23126602.

- "Arctic fox: Alopex lagopus". National Geographic. 10 September 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Boitani, L. (1984). Simon & Schuster's Guide to Mammals. Simon & Schuster/Touchstone Books, ISBN 978-0-671-42805-1

- Bininda-Emonds, O.R.P.; Gittleman, J.L. & Purvis, A. (1999). "Building large trees by combining phylogenetic information: a complete phylogeny of the extant Carnivora (Mammalia)". Biological Reviews. 74 (2): 143–175. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.328.7194. doi:10.1017/S0006323199005307. PMID 10396181. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014.

- Lindblad-Toh, K.; et al. (2005). "Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog". Nature. 438 (7069): 803–819. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..803L. doi:10.1038/nature04338. PMID 16341006.

- Audet, A.M.; Robbins, C.B. & Larivière, S. (2002). "Alopex lagopus" (PDF). Mammalian Species (713): 1–10. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2002)713<0001:AL>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 198969139. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2011.

- Larivière, S. (2002). "Vulpes zerda" (PDF). Mammalian Species (714): 1–5. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2002)714<0001:VZ>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 198968737. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2011.

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Tseng, Z.J.; Takeuchi, G.T.; Deng, T.; Xie, G.; Chang, M.M. & Wang, N. (2015). "Cenozoic vertebrate evolution and paleoenvironment in Tibetan Plateau: Progress and prospects". Gondwana Research. 27 (4): 1335–1354. Bibcode:2015GondR..27.1335W. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2014.10.014.

- The isolated beauty of Jan Mayen. Hurtigruten US

- Arctic fox. Nature Conservancy Canada

- Feldhamer, George A.; Thompson, B.C.; Chapman, J.A. (2003). Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation. JHU Press. pp. 511–540. ISBN 978-0-8018-7416-1.

- "Wildlife". Iceland Worldwide. iww.is. 2000. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- "The Arctic Fox Center". Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- Lai, S.; Bety, J.; Berteaux, D. (2017). "Movement tactics of a mobile predator in a meta-ecosystem with fluctuating resources: the arctic fox in the High Arctic". Oikos. 126 (7): 937–947. doi:10.1111/oik.03948.

- Specia, M. (2019). "An Arctic Fox's Epic Journey: Norway to Canada in 76 Days". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "Scientists 'speechless' at Arctic fox's epic trek". BBC News. July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "Naali Alopex lagopus" (in Finnish). Metsähallitus. 1 August 2011. Archived from the original on 14 December 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- Olli Järvinen & Kaarina Miettinen (1987). Sammuuko suuri suku? – Luonnon puolustamisen biologiaa (in Finnish). Vantaa: Suomen luonnonsuojelun tuki. pp. 95, 190. ISBN 951-9381-20-1.

- Bolen, Eric G. (1998). Ecology of North America. John Wiley and Sons. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-471-13156-4.

- Hannah, Lee (2010). Climate Change Biology. Academic Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-12-374182-0.

- Macdonald, David Whyte; Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio (2004). The biology and conservation of wild canids. Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-19-851556-2.

- Garrott, R. A.; Eberhardt, L. E. (1987). "Arctic fox". In Novak, M.; et al. (eds.). Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America. pp. 395–406. ISBN 978-0774393652.

- Tannerfeldt, M. (1997). Population fluctuations and life history consequences in the Arctic fox. Stockholm, Sweden: Dissertation, Stockholm University.

- Goltsman, M.; Kruchenkova, E. P.; MacDonald, D. W. (1996). "The Mednyi Arctic foxes: treating a population imperilled by disease". Oryx. 30 (4): 251–258. doi:10.1017/S0030605300021748.

- Lönnberg, E. (1927). Fjällrävsstammen i Sverige 1926. Uppsala, Sweden: Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

- Angerbjörn, A.; et al. (1995). "Dynamics of the Arctic fox population in Sweden". Annales Zoologici Fennici. 32: 55–68. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014.

- "Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 2003 – Schedule 2 Prohibited new organisms". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

Further reading

- Nowak, Ronald M. (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 0-8018-8032-7.