Walrus

The walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) is a large flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in the family Odobenidae and genus Odobenus. This species is subdivided into two subspecies:[2] the Atlantic walrus (O. r. rosmarus), which lives in the Atlantic Ocean, and the Pacific walrus (O. r. divergens), which lives in the Pacific Ocean.

| Walrus Temporal range: Pleistocene to Recent | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Male Pacific walrus | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Female Pacific walrus with young | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Clade: | Pinnipedia |

| Family: | Odobenidae |

| Genus: | Odobenus Brisson, 1762 |

| Species: | O. rosmarus |

| Binomial name | |

| Odobenus rosmarus | |

| Subspecies | |

|

O. rosmarus rosmarus | |

| |

| Distribution of walrus | |

| Synonyms | |

Adult walrus are characterised by prominent tusks and whiskers, and their considerable bulk: adult males in the Pacific can weigh more than 2,000 kilograms (4,400 pounds)[3] and, among pinnipeds, are exceeded in size only by the two species of elephant seals.[4] Walruses live mostly in shallow waters above the continental shelves, spending significant amounts of their lives on the sea ice looking for benthic bivalve mollusks to eat. Walruses are relatively long-lived, social animals, and they are considered to be a "keystone species" in the Arctic marine regions.

The walrus has played a prominent role in the cultures of many indigenous Arctic peoples, who have hunted the walrus for its meat, fat, skin, tusks, and bone. During the 19th century and the early 20th century, walruses were widely hunted and killed for their blubber, walrus ivory, and meat. The population of walruses dropped rapidly all around the Arctic region. Their population has rebounded somewhat since then, though the populations of Atlantic and Laptev walruses remain fragmented and at low levels compared with the time before human interference.

Etymology

The origin of the word walrus derives from a Germanic language, and it has been attributed largely to either the Dutch language or Old Norse. Its first part is thought to derive from a word such as Old Norse hvalr ('whale') and the second part has been hypothesized to come from the Old Norse word hross ('horse').[5] For example, the Old Norse word hrosshvalr means 'horse-whale' and is thought to have been passed in an inverted form to both Dutch and the dialects of northern Germany as walros and Walross.[6] An alternative theory is that it comes from the Dutch words wal 'shore' and reus 'giant'.[7]

The species name rosmarus is Scandinavian. The Norwegian manuscript Konungs skuggsjá, thought to date from around AD 1240, refers to the walrus as rosmhvalr in Iceland and rostungr in Greenland (walruses were by now extinct in Iceland and Norway, while the word evolved in Greenland). Several place names in Iceland, Greenland and Norway may originate from walrus sites: Hvalfjord, Hvallatrar and Hvalsnes to name some, all being typical walrus breeding grounds.

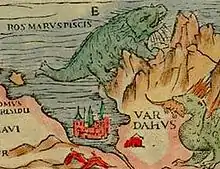

The archaic English word for walrus—morse—is widely thought to have come from the Slavic languages,[8] which in turn borrowed it from Finno-Ugric languages, and ultimately (according to Ante Aikio) from an unknown Pre-Finno-Ugric substrate language of Northern Europe.[9] Compare морж (morž) in Russian, mursu in Finnish, morša in Northern Saami, and morse in French. Olaus Magnus, who depicted the walrus in the Carta Marina in 1539, first referred to the walrus as the ros marus, probably a Latinization of morž, and this was adopted by Linnaeus in his binomial nomenclature.[10]

The coincidental similarity between morse and the Latin word morsus ('a bite') supposedly contributed to the walrus's reputation as a "terrible monster".[10]

The compound Odobenus comes from odous (Greek for 'teeth') and baino (Greek for 'walk'), based on observations of walruses using their tusks to pull themselves out of the water. The term divergens in Latin means 'turning apart', referring to their tusks.[11]

Taxonomy and evolution

The walrus is a mammal in the order Carnivora. It is the sole surviving member of the family Odobenidae, one of three lineages in the suborder Pinnipedia along with true seals (Phocidae) and eared seals (Otariidae). While there has been some debate as to whether all three lineages are monophyletic, i.e. descended from a single ancestor, or diphyletic, recent genetic evidence suggests all three descended from a caniform ancestor most closely related to modern bears.[12] Recent multigene analysis indicates the odobenids and otariids diverged from the phocids about 20–26 million years ago, while the odobenids and the otariids separated 15–20 million years ago.[13][14] Odobenidae was once a highly diverse and widespread family, including at least twenty species in the subfamilies Imagotariinae, Dusignathinae and Odobeninae.[15] The key distinguishing feature was the development of a squirt/suction feeding mechanism; tusks are a later feature specific to Odobeninae, of which the modern walrus is the last remaining (relict) species.

Two subspecies of walrus are widely recognized: the Atlantic walrus, O. r. rosmarus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the Pacific walrus, O. r. divergens (Illiger, 1815). Fixed genetic differences between the Atlantic and Pacific subspecies indicate very restricted gene flow, but relatively recent separation, estimated at 500,000 and 785,000 years ago.[16] These dates coincide with the hypothesis derived from fossils that the walrus evolved from a tropical or subtropical ancestor that became isolated in the Atlantic Ocean and gradually adapted to colder conditions in the Arctic.[16] From there, it presumably recolonized the North Pacific Ocean during high glaciation periods in the Pleistocene via the Central American Seaway.[13]

An isolated population in the Laptev Sea was considered by some authorities, including many Russian biologists and the canonical Mammal Species of the World,[2] to be a third subspecies, O. r. laptevi (Chapskii, 1940), but has since been determined to be of Pacific walrus origin.[17]

Anatomy

_skull_at_the_Royal_Veterinary_College_anatomy_museum.JPG.webp)

While some outsized Pacific males can weigh as much as 2,000 kg (4,400 lb), most weigh between 800 and 1,700 kg (1,800 and 3,700 lb). An occasional male of the Pacific subspecies far exceeds normal dimensions. In 1909, a walrus hide weighing 500 kg (1,100 lb) was collected from an enormous bull in Franz Josef Land, while in August 1910, Jack Woodson shot a 4.9-metre-long (16 ft) walrus, harvesting its 450 kg (1,000 lb) hide. Since a walrus's hide usually accounts for about 20% of its body weight, the total body mass of these two giants is estimated to have been at least 2,300 kg (5,000 lb).[18] The Atlantic subspecies weighs about 10–20% less than the Pacific subspecies.[4] Male Atlantic walrus weigh an average of 900 kg (2,000 lb).[3] The Atlantic walrus also tends to have relatively shorter tusks and somewhat more flattened snout. Females weigh about two-thirds as much as males, with the Atlantic females averaging 560 kg (1,230 lb), sometimes weighing as little as 400 kg (880 lb), and the Pacific female averaging 800 kg (1,800 lb).[19] Length typically ranges from 2.2 to 3.6 m (7 ft 3 in to 11 ft 10 in).[20][21] Newborn walruses are already quite large, averaging 33 to 85 kg (73 to 187 lb) in weight and 1 to 1.4 m (3 ft 3 in to 4 ft 7 in) in length across both sexes and subspecies.[1] All told, the walrus is the third largest pinniped species, after the two elephant seals. Walruses maintain such a high body weight because of the blubber stored underneath their skin. This blubber keeps them warm and the fat provides energy to the walrus.

The walrus's body shape shares features with both sea lions (eared seals: Otariidae) and seals (true seals: Phocidae). As with otariids, it can turn its rear flippers forward and move on all fours; however, its swimming technique is more like that of true seals, relying less on flippers and more on sinuous whole body movements.[4] Also like phocids, it lacks external ears.

The extraocular muscles of the walrus are well-developed. This and its lack of orbital roof allow it to protrude its eyes and see in both a frontal and dorsal direction. However, vision in this species appears to be more suited for short-range.[22]

Tusks and dentition

While this was not true of all extinct walruses,[23] the most prominent feature of the living species is its long tusks. These are elongated canines, which are present in both male and female walruses and can reach a length of 1 m (3 ft 3 in) and weigh up to 5.4 kg (12 lb).[24] Tusks are slightly longer and thicker among males, which use them for fighting, dominance and display; the strongest males with the largest tusks typically dominate social groups. Tusks are also used to form and maintain holes in the ice and aid the walrus in climbing out of water onto ice.[25] Tusks were once thought to be used to dig out prey from the seabed, but analyses of abrasion patterns on the tusks indicate they are dragged through the sediment while the upper edge of the snout is used for digging.[26] While the dentition of walruses is highly variable, they generally have relatively few teeth other than the tusks. The maximal number of teeth is 38 with dentition formula: 3.1.4.23.1.3.2, but over half of the teeth are rudimentary and occur with less than 50% frequency, such that a typical dentition includes only 18 teeth 1.1.3.00.1.3.0[4]

Vibrissae (whiskers)

Surrounding the tusks is a broad mat of stiff bristles ("mystacial vibrissae"), giving the walrus a characteristic whiskered appearance. There can be 400 to 700 vibrissae in 13 to 15 rows reaching 30 cm (12 in) in length, though in the wild they are often worn to much shorter lengths due to constant use in foraging.[27] The vibrissae are attached to muscles and are supplied with blood and nerves, making them highly sensitive organs capable of differentiating shapes 3 mm (1⁄8 in) thick and 2 mm (3⁄32 in) wide.[27]

Skin

Aside from the vibrissae, the walrus is sparsely covered with fur and appears bald. Its skin is highly wrinkled and thick, up to 10 cm (4 in) around the neck and shoulders of males. The blubber layer beneath is up to 15 cm (6 in) thick. Young walruses are deep brown and grow paler and more cinnamon-colored as they age. Old males, in particular, become nearly pink. Because skin blood vessels constrict in cold water, the walrus can appear almost white when swimming. As a secondary sexual characteristic, males also acquire significant nodules, called "bosses", particularly around the neck and shoulders.[25]

.jpeg.webp)

The walrus has an air sac under its throat which acts like a flotation bubble and allows it to bob vertically in the water and sleep. The males possess a large baculum (penis bone), up to 63 cm (25 in) in length, the largest of any land mammal, both in absolute size and relative to body size.[4]

Life history

Reproduction

Walruses live to about 20–30 years old in the wild.[28] The males reach sexual maturity as early as seven years, but do not typically mate until fully developed at around 15 years of age.[4] They rut from January through April, decreasing their food intake dramatically. The females begin ovulating as soon as four to six years old.[4] The females are diestrous, coming into heat in late summer and also around February, yet the males are fertile only around February; the potential fertility of this second period is unknown. Breeding occurs from January to March, peaking in February. Males aggregate in the water around ice-bound groups of estrous females and engage in competitive vocal displays.[29] The females join them and copulate in the water.[25]

Gestation lasts 15 to 16 months. The first three to four months are spent with the blastula in suspended development before it implants itself in the uterus. This strategy of delayed implantation, common among pinnipeds, presumably evolved to optimize both the mating season and the birthing season, determined by ecological conditions that promote newborn survival.[30] Calves are born during the spring migration, from April to June. They weigh 45 to 75 kg (99 to 165 lb) at birth and are able to swim. The mothers nurse for over a year before weaning, but the young can spend up to five years with the mothers.[25] Walrus milk contains higher amounts of fats and protein compared to land animals but lower compared to phocid seals.[31] This lower fat content in turn causes a slower growth rate among calves and a longer nursing investment for their mothers.[32] Because ovulation is suppressed until the calf is weaned, females give birth at most every two years, leaving the walrus with the lowest reproductive rate of any pinniped.[33]

Migration

The rest of the year (late summer and fall), walruses tend to form massive aggregations of tens of thousands of individuals on rocky beaches or outcrops. The migration between the ice and the beach can be long-distance and dramatic. In late spring and summer, for example, several hundred thousand Pacific walruses migrate from the Bering Sea into the Chukchi Sea through the relatively narrow Bering Strait.[25][34]

Ecology

Range and habitat

The majority of the population of the Pacific walrus spends its summers north of the Bering Strait in the Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean along the northern coast of eastern Siberia, around Wrangel Island, in the Beaufort Sea along the northern shore of Alaska south to Unimak Island,[35] and in the waters between those locations. Smaller numbers of males summer in the Gulf of Anadyr on the southern coast of the Siberian Chukchi Peninsula, and in Bristol Bay off the southern coast of Alaska, west of the Alaska Peninsula. In the spring and fall, walruses congregate throughout the Bering Strait, reaching from the western coast of Alaska to the Gulf of Anadyr. They winter over in the Bering Sea along the eastern coast of Siberia south to the northern part of the Kamchatka Peninsula, and along the southern coast of Alaska.[4] A 28,000-year-old fossil walrus was dredged up from the bottom of San Francisco Bay, indicating that Pacific walruses ranged that far south during the last Ice Age.[36]

Commercial harvesting reduced the population of the Pacific walrus to between 50,000 and 100,000 in the 1950s-1960s. Limits on commercial hunting allowed the population to increase to a peak in the 1970s-1980s, but subsequently, walrus numbers have again declined. Early aerial censuses of Pacific walrus conducted at five-year intervals between 1975 and 1985 estimated populations of above 220,000 in each of the three surveys.[37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45]

In 2006, the population of the Pacific walrus was estimated to be around 129,000 on the basis of an aerial census combined with satellite tracking.[46][47] There were roughly 200,000 Pacific walruses in 1990.[48][49]

The much smaller population of Atlantic walruses ranges from the Canadian Arctic, across Greenland, Svalbard, and the western part of Arctic Russia. There are eight hypothetical subpopulations of Atlantic walruses, based largely on their geographical distribution and movements: five west of Greenland and three east of Greenland.[50] The Atlantic walrus once ranged south to Sable Island, Nova Scotia, and as late as the 18th century was found in large numbers in the Greater Gulf of St. Lawrence region, sometimes in colonies of up to 7,000 to 8,000 individuals.[51] This population was nearly eradicated by commercial harvest; their current numbers, though difficult to estimate, probably remain below 20,000.[52][53] In April 2006, the Canadian Species at Risk Act listed the population of the northwestern Atlantic walrus in Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador as having been eradicated in Canada.[54] A genetically distinct population existed in Iceland that was wiped out after Norse settlement around 1213–1330 AD.[55]

The isolated population of Laptev Sea walruses is confined year-round to the central and western regions of the Laptev Sea, the eastmost regions of the Kara Sea, and the westmost regions of the East Siberian Sea. The current population of these walruses has been estimated to be between 5,000 and 10,000.[56]

Even though walruses can dive to depths beyond 500 meters, they spend most of their time in shallow waters (and the nearby ice floes) hunting for food.[57][58]

In March 2021, a single walrus, nicknamed Wally the Walrus, was sighted at Valentia Island, Ireland, far south of its typical range, potentially due to having fallen asleep on an iceberg that then drifted south towards Ireland.[59] Days later, a walrus, thought to be the same animal, was spotted on the Pembrokeshire coast, Wales.[60] In June 2022, a single walrus was sighted on the shores of the Baltic Sea - at Rügen Island, Germany, Mielno, Poland and Skälder Bay, Sweden.[61] [62][63] In July 2022, there was a report of a lost, starving walrus (nicknamed as Stena) in the coastal waters of the towns of Hamina and Kotka in Kymenlaakso, Finland,[64][65] that, despite rescue attempts, died of starvation when the rescuers tried to transport it to the Korkeasaari Zoo for treatment.[66][67]

Diet

Walruses prefer shallow shelf regions and forage primarily on the sea floor, often from sea ice platforms.[4] They are not particularly deep divers compared to other pinnipeds; the deepest dives in a study of Atlantic walrus near Svalbard were only 31±17 m (102 ft)[68] but a more recent study recorded dives exceeding 500 m (1640 ft) in Smith Sound, between NW Greenland and Arctic Canada - in general peak dive depth can be expected to depend on prey distribution and seabed depth.[58]

The walrus has a diverse and opportunistic diet, feeding on more than 60 genera of marine organisms, including shrimp, crabs, tube worms, soft corals, tunicates, sea cucumbers, various mollusks (such as snails, octopuses, and squid), some types of slow-moving fish,[69] and even parts of other pinnipeds.[70] However, it prefers benthic bivalve mollusks, especially clams, for which it forages by grazing along the sea bottom, searching and identifying prey with its sensitive vibrissae and clearing the murky bottoms with jets of water and active flipper movements.[71] The walrus sucks the meat out by sealing its powerful lips to the organism and withdrawing its piston-like tongue rapidly into its mouth, creating a vacuum. The walrus palate is uniquely vaulted, enabling effective suction. The diet of the Pacific walrus consist almost exclusively of benthic invertebrates (97 percent).[72]

Aside from the large numbers of organisms actually consumed by the walrus, its foraging has a large peripheral impact on benthic communities. It disturbs (bioturbates) the sea floor, releasing nutrients into the water column, encouraging mixing and movement of many organisms and increasing the patchiness of the benthos.[26]

Seal tissue has been observed in a fairly significant proportion of walrus stomachs in the Pacific, but the importance of seals in the walrus diet is under debate.[73] There have been isolated observations of walruses preying on seals up to the size of a 200 kg (440 lb) bearded seal.[74][75] Rarely, incidents of walruses preying on seabirds, particularly the Brünnich's guillemot (Uria lomvia), have been documented.[76] Walruses may occasionally prey on ice-entrapped narwhals and scavenge on whale carcasses but there is little evidence to prove this.[77][78]

Predators

Due to its great size and tusks, the walrus has only two natural predators: the orca and the polar bear.[79] The walrus does not, however, comprise a significant component of either of these predators' diets. Both the orca and the polar bear are also most likely to prey on walrus calves. The polar bear often hunts the walrus by rushing at beached aggregations and consuming the individuals crushed or wounded in the sudden exodus, typically younger or infirm animals.[80] The bears also isolate walruses when they overwinter and are unable to escape a charging bear due to inaccessible diving holes in the ice.[81] However, even an injured walrus is a formidable opponent for a polar bear, and direct attacks are rare. Armed with its ivory tusks, walruses have been known to fatally injure polar bears in battles if the latter follows the other into the water, where the bear is at a disadvantage.[82] Polar bear–walrus battles are often extremely protracted and exhausting, and bears have been known to break away from the attack after injuring a walrus. Orcas regularly attack walruses, although walruses are believed to have successfully defended themselves via counterattack against the larger cetacean.[83] However, orcas have been observed successfully attacking walruses with few or no injuries.[84]

Relationship with humans

Conservation

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the walrus was heavily exploited by American and European sealers and whalers, leading to the near-extirpation of the Atlantic subspecies.[85] Commercial walrus harvesting is now outlawed throughout its range, although Chukchi, Yupik and Inuit peoples[86] are permitted to kill small numbers towards the end of each summer.

Traditional hunters used all parts of the walrus.[87] The meat, often preserved, is an important winter nutrition source; the flippers are fermented and stored as a delicacy until spring; tusks and bone were historically used for tools, as well as material for handicrafts; the oil was rendered for warmth and light; the tough hide made rope and house and boat coverings; and the intestines and gut linings made waterproof parkas. While some of these uses have faded with access to alternative technologies, walrus meat remains an important part of local diets,[88] and tusk carving and engraving remain a vital art form.

According to Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, European hunters and Arctic explorers found walrus meat not particularly tasty, and only ate it in case of necessity; however walrus tongue was a delicacy.[89]

Hunter sitting on dozens of walruses killed for their tusks, 1911

Hunter sitting on dozens of walruses killed for their tusks, 1911 Walrus tusk scrimshaw made by Chukchi artisans depicting polar bears attacking walruses, on display in the Magadan Regional Museum, Magadan, Russia

Walrus tusk scrimshaw made by Chukchi artisans depicting polar bears attacking walruses, on display in the Magadan Regional Museum, Magadan, Russia.jpg.webp) Trained walrus in captivity at Marineland

Trained walrus in captivity at Marineland

Walrus hunts are regulated by resource managers in Russia, the United States, Canada, and Greenland (self-governing country in the Kingdom of Denmark), and representatives of the respective hunting communities. An estimated four to seven thousand Pacific walruses are harvested in Alaska and in Russia, including a significant portion (about 42%) of struck and lost animals.[90] Several hundred are removed annually around Greenland.[91] The sustainability of these levels of harvest is difficult to determine given uncertain population estimates and parameters such as fecundity and mortality. The Boone and Crockett Big Game Record book has entries for Atlantic and Pacific walrus. The recorded largest tusks are just over 30 inches and 37 inches long respectively.[92]

The effects of global climate change are another element of concern. The extent and thickness of the pack ice has reached unusually low levels in several recent years. The walrus relies on this ice while giving birth and aggregating in the reproductive period. Thinner pack ice over the Bering Sea has reduced the amount of resting habitat near optimal feeding grounds. This more widely separates lactating females from their calves, increasing nutritional stress for the young and lower reproductive rates.[93] Reduced coastal sea ice has also been implicated in the increase of stampeding deaths crowding the shorelines of the Chukchi Sea between eastern Russia and western Alaska.[94][95] Analysis of trends in ice cover published in 2012 indicate that Pacific walrus populations are likely to continue to decline for the foreseeable future, and shift further north, but that careful conservation management might be able to limit these effects.[96]

Currently, two of the three walrus subspecies are listed as "least-concern" by the IUCN, while the third is "data deficient".[1] The Pacific walrus is not listed as "depleted" according to the Marine Mammal Protection Act nor as "threatened" or "endangered" under the Endangered Species Act. The Russian Atlantic and Laptev Sea populations are classified as Category 2 (decreasing) and Category 3 (rare) in the Russian Red Book.[56] Global trade in walrus ivory is restricted according to a CITES Appendix 3 listing. In October 2017, the Center for Biological Diversity announced they would sue the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to force it to classify the Pacific Walrus as a threatened or endangered species.[97]

In 1952, walruses in Svalbard were nearly gone due to ivory hunting over a 300 years period, but the Norwegian government banned their commercial hunting and the walruses began to rebound in 2006, making their population increase to 2,629.

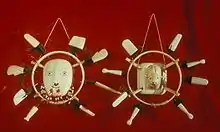

Folklore

The walrus plays an important role in the religion and folklore of many Arctic peoples. Skin and bone are used in some ceremonies, and the animal appears frequently in legends. For example, in a Chukchi version of the widespread myth of the Raven, in which Raven recovers the sun and the moon from an evil spirit by seducing his daughter, the angry father throws the daughter from a high cliff and, as she drops into the water, she turns into a walrus – possibly the original walrus. According to various legends, the tusks are formed either by the trails of mucus from the weeping girl or her long braids.[98] This myth is possibly related to the Chukchi myth of the old walrus-headed woman who rules the bottom of the sea, who is in turn linked to the Inuit goddess Sedna. Both in Chukotka and Alaska, the aurora borealis is believed to be a special world inhabited by those who died by violence, the changing rays representing deceased souls playing ball with a walrus head.[98][99]

Walrus ivory masks made by Yupik in Alaska

Walrus ivory masks made by Yupik in Alaska John Tenniel's illustration for Lewis Carroll's poem "The Walrus and the Carpenter"

John Tenniel's illustration for Lewis Carroll's poem "The Walrus and the Carpenter" Dutch explorers fight a walrus on the coast of Novaya Zemlya, 1596

Dutch explorers fight a walrus on the coast of Novaya Zemlya, 1596

Most of the distinctive 12th-century Lewis Chessmen from northern Europe are carved from walrus ivory, though a few have been found to be made of whales' teeth.

Literature

Because of its distinctive appearance, great bulk, and immediately recognizable whiskers and tusks, the walrus also appears in the popular cultures of peoples with little direct experience with the animal, particularly in English children's literature. Perhaps its best-known appearance is in Lewis Carroll's whimsical poem "The Walrus and the Carpenter" that appears in his 1871 book Through the Looking-Glass. In the poem, the eponymous antiheroes use trickery to consume a great number of oysters. Although Carroll accurately portrays the biological walrus's appetite for bivalve mollusks, oysters, primarily nearshore and intertidal inhabitants, these organisms in fact comprise an insignificant portion of its diet in captivity.[100]

The "walrus" in the cryptic Beatles song "I Am the Walrus" is a reference to the Lewis Carroll poem.[101]

Another appearance of the walrus in literature is in the story "The White Seal" in Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book, where it is the "old Sea Vitch—the big, ugly, bloated, pimpled, fat-necked, long-tusked walrus of the North Pacific, who has no manners except when he is asleep".[102]

See also

References

- Lowry, L. (2016). "Odobenus rosmarus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15106A45228501. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T15106A45228501.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Wozencraft WC (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson DE, Reeder DM (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "Walrus: Physical Characteristics". seaworld.org. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012.

- Fay FH (1985). "Odobenus rosmarus". Mammalian Species (238): 1–7. doi:10.2307/3503810. JSTOR 3503810. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- "Walrus". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Nielsen NÅ (1976). Dansk Etymologisk Ordbog: Ordenes Historie. Gyldendal.

- "Etymology of mammal names". Iberianature.com. 29 December 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- "morse, n., etymology of". The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). OED Online. Oxford University Press. 1989.

- Luobbal Sámmol Sámmol Ánte (Ante Aikio). "An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory" (PDF). Giellagas Institute University of Oulu. p. 85.

- Allen JA (1880). History of North American pinnipeds, US Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territorie. Arno Press Inc. (1974 reprint). ISBN 978-0-405-05702-1.

- "Odobenus rosmarus - Society for Marine Mammalogy". marinemammalscience.org. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- Lento GM, Hickson RE, Chambers GK, Penny D (January 1995). "Use of spectral analysis to test hypotheses on the origin of pinnipeds". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 12 (1): 28–52. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040189. PMID 7877495.

- Arnason U, Gullberg A, Janke A, Kullberg M, Lehman N, Petrov EA, Väinölä R (November 2006). "Pinniped phylogeny and a new hypothesis for their origin and dispersal". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 41 (2): 345–54. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.022. PMID 16815048.

- Higdon JW, Bininda-Emonds OR, Beck RM, Ferguson SH (November 2007). "Phylogeny and divergence of the pinnipeds (Carnivora: Mammalia) assessed using a multigene dataset". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 216. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-216. PMC 2245807. PMID 17996107.

- Kohno N (2006). "A new Miocene Odobenid (Mammalia: Carnivora) from Hokkaido, Japan, and its implications for odobenid phylogeny". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (2): 411–421. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[411:ANMOMC]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85679558.

- Hoelzel AR, ed. (2002). Marine mammal biology: an evolutionary approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-632-05232-5.

- Higdon JW, Stewart DB (2018). "State of Circumpolar Walrus Populations : Odobenus rosmarus" (PDF). WWF Arctic Programme. p. 6.

- Wood G (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- Carling M (1999). "Odobenus rosmarus walrus". Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016.

- McIntyre T (11 November 2010). "Walrus. Odobenus rosmarus". National Geographic.

- "Hinterland Who's Who – Atlantic walrus". Hww.ca. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- Kastelein RA (26 February 2009). "Walrus Odobenus rosmarus". In Perrin WF, Wursig B, Thewissen JG (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. p. 1214. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- Magallanes I, Parham JF, Santos GP, Velez-Juarbe J (2018). "A new tuskless walrus from the Miocene of Orange County, California, with comments on the diversity and taxonomy of odobenids". PeerJ. 6: e5708. doi:10.7717/peerj.5708. PMC 6188011. PMID 30345169.

- Berta A, Sumich JL (1999). Marine mammals: evolutionary biology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Fay FH (1982). "Ecology and Biology of the Pacific Walrus, Odobenus rosmarus divergens Illiger". North American Fauna. 74: 1–279. doi:10.3996/nafa.74.0001.

- Ray C, McCormick-Ray J, Berg P, Epstein HE (2006). "Pacific Walrus: Benthic bioturbator of Beringia". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 330: 403–419. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2005.12.043.

- Kastelein RA, Stevens S, Mosterd P (1990). "The sensitivity of the vibrissae of a Pacific Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus divergens). Part 2: Masking" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 16 (2): 78–87.

- Fay FH (1960). "Carnivorous walrus and some arctic zoonoses" (PDF). Arctic. 13 (2): 111–122. doi:10.14430/arctic3691. Comment

- Nowicki SN, Stirling I, Sjare B (1997). "Duration of stereotypes underwater vocal displays by make Atlantic walruses in relation to aerobic dive limit". Marine Mammal Science. 13 (4): 566–575. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1997.tb00084.x.

- Sandell M (March 1990). "The evolution of seasonal delayed implantation". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 65 (1): 23–42. doi:10.1086/416583. PMID 2186428. S2CID 35615292.

- Riedman M (1990). The pinnipeds : seals, sea lions, and walruses. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0520064973.

- Marsden T, Murdoch J, eds. (2006). Current Topics in Developmental Biology, Volume 72 (1st ed.). Burlington: Elsevier. p. 277. ISBN 978-0080463414.

- Evans PG, Raga JA, eds. (2001). Marine mammals: biology and conservation. London & New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-46573-4.

- Fischbach AS, Kochnev AA, Garlich-Miller JL, Jay CV (2016). Pacific Walrus Coastal Haulout Database, 1852–2016—Background Report. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- "Izembek National Wildlife Report Sept 2015" (PDF). USFWS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Dyke AS (1999). "The Late Wisconsinan and Holocene record of walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) from North America: A review with new data from Arctic and Atlantic Canada". Arctic. 52 (2): 160–181. doi:10.14430/arctic920.

- Estes JA, Gol'tsev VN (1984). "Abundance and distribution of the Pacific walrus (Odobenus rosmarus divergens): results of the first Soviet American joint aerial survey, autumn 1975.". Soviet American Cooperative Research on Marine Mammals. Vol. 1 Pinnipeds. NOAA, Technical Report, NMFS 12. pp. 67–76.

- Estes JA, Gilbert JR (1978). "Evaluation of an aerial survey of Pacific walruses (Odobenus rosmarus divergens)". Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. 35 (8): 1130–1140. doi:10.1139/f78-178.

- Gol'tsev VN (1976). Aerial surveys of Pacific walruses in the Soviet sector during fall 1975. Magadan: Procedural Report TINRO.

- Johnson A, Burns J, Dusenberry W, Jones R (1982). Aerial survey of Pacific walruses, 1980. Anchorage, Alaska: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Marine Mammals Management.

- Fedoseev GA (1984). "Present status of the population of walruses (Odobenus rosmarus) in the eastern Arctic and Bering Sea". In Rodin VE, Perlov AS, Berzin AA, Gavrilov GM, Shevchenko AI, Fadeev NS, Kucheriavenko EB (eds.). Marine Mammals of the Far East. Vladivostok: TINRO. pp. 73–85.

- Gilbert JR (1986). Aerial survey of Pacific walruses in the Chukchi Sea, 1985. Mimeo Report.

- Gilbert JR (1989). "Aerial census of Pacific walruses in the Chukchi Sea, 1985". Marine Mammal Science. 5: 17–28. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1989.tb00211.x.

- Gilbert JR (1989). "Errata: Correction to the variance of products, estimates of Pacific walrus populations". Marine Mammal Science. 5: 411–412. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1989.tb00356.x.

- Fedoseev GA, Razlivalov EV (1986). The distribution and abundance of walruses in the eastern Arctic and Bering Sea in autumn 1985. Magadan: VNIRO.

- Speckman SG, Chernook VI, Burn DM, Udevitz MS, Kochnev AA, Vasilev A, Jay CV, Lisovsky A, Fischbach AS, Benter RB, et al. (2010). "Results and evaluation of a survey to estimate Pacific walrus population size, 2006". Marine Mammal Science. 27 (3): 514–553. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00419.x.

- US Fish and Wildlife Service (2014). "Stock Assessment Report: Pacific Walrus – Alaska Stock" (PDF).

- Gilbert JR (1992). "Aerial census of Pacific walrus, 1990". USFWS R7/MMM Technical Report 92-1.

- US Fish and Wildlife Service (2002). "Stock Assessment Report: Pacific Walrus – Alaska Stock" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- Born E, Andersen L, Gjertz I, Wiig Ø (2001). "A review of the genetic relationships of Atlantic walrus (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) east and west of Greenland". Polar Biology. 24 (10): 713–718. doi:10.1007/s003000100277. S2CID 191312.

- Bolster WJ (2012). The Mortal Sea: Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- [NAMMCO] North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission. (1995). Report of the third meeting of the Scientific Committee. NAMMCO Annual Report 1995. Tromsø: NAMMCO. pp. 71–127.

- North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission. "Status of Marine Mammals of the North Atlantic: The Atlantic Walrus" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. "Atlantic Walrus: Northwest Atlantic Population". Archived from the original on 18 August 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- Keighley X, Pálsson S, Einarsson BF, Petersen A, Fernández-Coll M, Jordan P, et al. (December 2019). "Disappearance of Icelandic Walruses Coincided with Norse Settlement". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (12): 2656–2667. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz196. PMC 6878957. PMID 31513267.

- "Морж / Odobenus rosmarus". Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation protected species list. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- "Walrus Facts". World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

- Garde E, Jung-Madsen S, Ditlevsen S, Hansen RG, Zinglersen KB, Heide-Jørgensen MP (March 2018). "Diving behavior of the Atlantic walrus in high Arctic Greenland and Canada". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 500: 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2017.12.009.

- Kelleher L, Palenque BK (14 March 2021). "First ever sighting of a walrus in Ireland after it is thought to have drifted across Atlantic after falling asleep on iceberg". independent.ie. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- "Walrus spotted in Wales, days after one seen off Ireland". bbc.co.uk. BBC News. 20 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- "Walrus makes rare stop on German beach to delight of locals". 17 June 2022.

- "Walrus spotted on Baltic beach in first ever sighting in Poland". 24 June 2022.

- "Photo Story: Rare visit by Walrus in Skane, Sweden". 12 June 2022.

- "Visiting walrus causes stir in southern Finland town". Yle News. 15 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "The walrus destroyed equipment worth more than 10,000 euros, says a Kotka fisherman". Nord News. 18 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Roscoe, Matthew (20 July 2022). "UPDATE: Walrus found on the shore in Hamina, Finland has died, causing some outrage". EuroWeekly News. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Walrus' fate sparks online outrage". Yle. 22 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- Schreer JF, Kovacs KM, O'Hara Hines RJ (2001). "Comparative diving patterns of pinnipeds and seabirds". Ecological Monographs. 71: 137–162. doi:10.1890/0012-9615(2001)071[0137:CDPOPA]2.0.CO;2.

- "Walrus - Facts, Diet, Habitat & Pictures on Animalia.bio".

- Sheffield G, Fay FH, Feder H, Kelly BP (2001). "Laboratory digestion of prey and interpretation of walrus stomach contents". Marine Mammal Science. 17 (2): 310–330. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01273.x.

- Levermann N, Galatius A, Ehlme G, Rysgaard S, Born EW (October 2003). "Feeding behaviour of free-ranging walruses with notes on apparent dextrality of flipper use". BMC Ecology. 3 (9): 9. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-3-9. PMC 270045. PMID 14572316.

- "Chapter 4.9.8.5: Other Pinnipeds". Alaska Groundfish Fisheries Final Programic Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement. Fishery Management Plans for the Groundfish Fishery of the Gulf of Alaska and the Groundfish of the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands Area: Environmental Impact Statement. 21 December 2018 – via Google Books.

- Lowry LF, Frost KJ (1981). "Feeding and Trophic Relationships of Phocid Seals and walruses in the Eastern Bering Sea". In National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (ed.). The Eastern Bering Sea Shelf: Oceanography & Resources vol. 2. University of Washington Press. pp. 813–824.

- Fay FH (1985). "Odobenus rosmarus" (PDF). Mammalian Species (238): 1–7. doi:10.2307/3503810. JSTOR 3503810. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2013.

- "Photos from Trips to Pyramiden". Spitsbergen Online. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- Mallory ML, Woo K, Gaston A, Davies WE, Mineau P (2004). "Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) predation on adult thick-billed murres (Uria lomvia) at Coats Island, Nunavut, Canada". Polar Research. 23 (1): 111–114. Bibcode:2004PolRe..23..111M. doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.2004.tb00133.x.

- "Narwhals, Narwhal Pictures, Narwhal Facts". National Geographic. 11 November 2010.

- "Walrus facts". Canadian Geographic. 4 April 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- Mr. Appliance. "Walrus Predators". Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- Ovsyanikov N (1992). "Ursus ubiquitous". BBC Wildlife. 10 (12): 18–26.

- Calvert W, Stirling I (1990). "Interactions between Polar Bears and Overwintering Walruses in the Central Canadian High Arctic". Bears: Their Biology and Management. 8: 351–356. doi:10.2307/3872939. JSTOR 3872939. S2CID 134001816.

- "North American Bear Center – Polar Bear Facts". North American Bear Center. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Jefferson TA, Stacey PJ, Baird RW (1991). "A review of Killer Whale interactions with other marine mammals: Predation to co-existence" (PDF). Mammal Review. 21 (4): 151. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1991.tb00291.x.

- Kryukova NV, Kruchenkova EP, Ivanov DI (2012). "Killer whales (Orcinus orca) hunting for walruses (Odobenus rosmarus divergens) near Retkyn Spit, Chukotka". Biology Bulletin. 39 (9): 768–778. doi:10.1134/S106235901209004X. S2CID 16477223.

- Bockstoce JR, Botkin DB (1982). "The Harvest of Pacific Walruses by the Pelagic Whaling Industry, 1848 to 1914". Arctic and Alpine Research. 14 (3): 183–188. doi:10.2307/1551150. JSTOR 1551150.

- Chivers CJ (25 August 2002). "A Big Game". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- US Fish and Wildlife Service (2007). "Hunting and Use of Walrus by Alaska Natives" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- Eleanor EW, Freeman MM, Makus JC (1996). "Use and preference for Traditional Foods among Belcher Island Inuit". Arctic. 49 (3): 256–264. doi:10.14430/arctic1201. JSTOR 40512002. S2CID 53985170.

- Nordenskiöld AE (1882). The Voyage of the Vega Round Asia and Europe: With a Historical Review of Previous Journeys Along the North Coast of the Old World Collection Léo Pariseau. Translated by Leslie A. Macmillan and Company. p. 122.

- Garlich-Miller JG, Burn DM (1997). "Estimating the harvest of Pacific walrus, Odobenus rosmarus divergens, in Alaska". Fishery Bulletin. 97 (4): 1043–1046.

- Witting L, Born EW (2005). "An assessment of Greenland walrus populations". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 62 (2): 266–284. doi:10.1016/j.icesjms.2004.11.001.

- "B&C World's Record - Atlantic Walrus". Boone and Crockett Club. 29 October 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- Kaufman M (15 April 2006). "Warming Arctic Is Taking a Toll, Peril to Walrus Young Seen as Result of Melting Ice Shelf". The Washington Post. p. A7. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- Revkin AC (2 October 2009). "Global warming could reverse a walrus comeback". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Sundt N (18 September 2009). "As Arctic Sea ice reaches annual minimum, large number of walrus corpses found". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on 24 September 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Maccracken JG (August 2012). "Pacific Walrus and climate change: observations and predictions". Ecology and Evolution. 2 (8): 2072–90. doi:10.1002/ece3.317. PMC 3434008. PMID 22957206.

- Joling D (12 October 2017). "Group plans to sue over walrus protection". The Mercury News. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- Bogoras W (1902). "The Folklore of Northeastern Asia, as Compared with That of Northwestern America". American Anthropologist. 4 (4): 577–683. doi:10.1525/aa.1902.4.4.02a00020.

- Boas F (1901). "The Eskimo of Baffin Land and Hudson Bay". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 15: 146.

- Kastelein RA, Wiepkema PR, Slegtenhorst C (1989). "The use of molluscs to occupy Pacific walrusses (Odobenus rosmarus divergens) in human care" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 15 (1): 6–8.

- Zimmer B (24 November 2017). "The Delights of Parsing the Beatles' Most Nonsensical Song". The Atlantic. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Kipling R (1994) [1894]. The Jungle Book. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Popular Classics. p. 84. ISBN 0-14-062104-0.

Further reading

- Heptner VG, Nasimovich AA, Bannikov AG, Hoffmann RS (1996). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. 2 part 3. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation.

External links

Data related to Odobenus rosmarus at Wikispecies

Data related to Odobenus rosmarus at Wikispecies Media related to Odobenus rosmarus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Odobenus rosmarus at Wikimedia Commons- Biologist Tracks Walruses Forced Ashore As Ice Melts – audio report by NPR

- Thousands Of Walruses Crowd Ashore Due To Melting Sea Ice – video by National Geographic

- Voices in the Sea – Sounds of the Walrus Archived 9 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine