Finland

Finland (Finnish: Suomi [ˈsuo̯mi] (![]() listen); Swedish: Finland [ˈfɪ̌nland] (

listen); Swedish: Finland [ˈfɪ̌nland] (![]() listen)), officially the Republic of Finland (Finnish: Suomen tasavalta; Swedish: Republiken Finland (

listen)), officially the Republic of Finland (Finnish: Suomen tasavalta; Swedish: Republiken Finland (![]() listen to all)),[note 2] is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland across Estonia to the south. Finland covers an area of 338,455 square kilometres (130,678 sq mi) with a population of 5.6 million. Helsinki is the capital and largest city, forming a larger metropolitan area with the neighbouring cities of Espoo, Kauniainen, and Vantaa. The vast majority of the population are ethnic Finns. Finnish, alongside Swedish, are the official languages. Swedish is the native language of 5.2% of the population.[11] Finland's climate varies from humid continental in the south to the boreal in the north. The land cover is primarily a boreal forest biome, with more than 180,000 recorded lakes.[12]

listen to all)),[note 2] is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland across Estonia to the south. Finland covers an area of 338,455 square kilometres (130,678 sq mi) with a population of 5.6 million. Helsinki is the capital and largest city, forming a larger metropolitan area with the neighbouring cities of Espoo, Kauniainen, and Vantaa. The vast majority of the population are ethnic Finns. Finnish, alongside Swedish, are the official languages. Swedish is the native language of 5.2% of the population.[11] Finland's climate varies from humid continental in the south to the boreal in the north. The land cover is primarily a boreal forest biome, with more than 180,000 recorded lakes.[12]

Republic of Finland | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms

| |

| Anthem: Maamme (Finnish) Vårt land (Swedish) (English: "Our Land") | |

.svg.png.webp)  Location of Finland (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Helsinki 60°10′15″N 24°56′15″E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognized national languages |

|

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2021)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic[4] |

| Sauli Niinistö | |

• Prime Minister | Sanna Marin |

• Speaker of the Parliament | Matti Vanhanen |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence from Russia | |

• Integration and autonomy in the Russian Empire | 29 March 1809 |

• Declaration of Independence | 6 December 1917 |

| January – May 1918 | |

• Constitution established | 17 July 1919 |

| 30 November 1939 – 13 March 1940 | |

| 25 June 1941 – 19 September 1944 | |

• Joined the EU | 1 January 1995 |

| Area | |

• Total | 338,455 km2 (130,678 sq mi) (65th) |

• Water (%) | 9.71 (2015)[5] |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | |

• Density | 16.4/km2 (42.5/sq mi) (213th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 11th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| UTC+3 (EEST) | |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy[10] |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +358 |

| ISO 3166 code | FI |

| Internet TLD | .fi, .axa |

| |

Finland was first inhabited around 9000 BC after the Last Glacial Period.[13] The Stone Age introduced several different ceramic styles and cultures. The Bronze Age and Iron Age were characterized by extensive contacts with other cultures in Fennoscandia and the Baltic region.[14] From the late 13th century, Finland gradually became an integral part of Sweden as a consequence of the Northern Crusades. In 1809, as a result of the Finnish War, Finland became part of the Russian Empire as the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland, during which Finnish art flourished and the idea of independence began to take hold. In 1906, Finland became the first European state to grant universal suffrage, and the first in the world to give all adult citizens the right to run for public office.[15][16] Nicholas II, the last Tsar of Russia, tried to russify Finland and terminate its political autonomy, but after the 1917 Russian Revolution, Finland declared independence from Russia. In 1918, the fledgling state was divided by the Finnish Civil War. During World War II, Finland fought the Soviet Union in the Winter War and the Continuation War, and Nazi Germany in the Lapland War. It subsequently lost parts of its territory, but maintained its independence.

Finland largely remained an agrarian country until the 1950s. After World War II, it rapidly industrialized and developed an advanced economy, while building an extensive welfare state based on the Nordic model; the country soon enjoyed widespread prosperity and a high per capita income.[17] Finland joined the United Nations in 1955 and adopted an official policy of neutrality; it joined the OECD in 1969, the NATO Partnership for Peace in 1994,[18] the European Union in 1995, the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council in 1997,[18] and the Eurozone at its inception in 1999. Finland is a top performer in numerous metrics of national performance, including education, economic competitiveness, civil liberties, quality of life and human development.[19][20][21][22] In 2015, Finland ranked first in the World Human Capital,[23] topped the Press Freedom Index, and was the most stable country in the world during 2011–2016, according to the Fragile States Index;[24] it is second in the Global Gender Gap Report,[25] and has ranked first in every annual World Happiness Report since 2018.[26][27][28]

Etymology

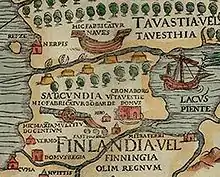

The earliest written appearance of the name Finland is thought to be on three runestones. Two of them have the inscription finlonti (U 582) and the third has the inscription finlandi (G 319) and dates back to the 13th century.[29]

The name Suomi (Finnish for 'Finland') has uncertain origins, but a common etymology with saame (the Sami, the native people of Lapland) and Häme (a province in the inland) has been suggested.[30] [31] In addition to the close relatives of Finnish (the Finnic languages), this name is also used in the Baltic languages Latvian (soms, Somija) and Lithuanian (suomis, Suomija), although these are later borrowings. An alternative hypothesis suggests the Proto-Indo-European word *(dʰ)ǵʰm-on- 'human' (Latin homo), being borrowed into Uralic as *ćoma.[31]

In the earliest historical sources, from the 12th and 13th centuries, the term Finland refers to the coastal region around Turku. This region later became known as Finland Proper in distinction from the country name Finland. Finland became a common name for the whole country in a centuries-long process that started when the Catholic Church established a missionary diocese in the province of Suomi possibly sometime in the 12th century.[32]

The devastation of Finland during the Great Northern War (1714–1721) and during the Russo-Swedish War (1741–1743) caused Sweden to begin carrying out major efforts to defend its eastern half from Russia. These 18th-century experiences created a sense of a shared destiny that when put in conjunction with the unique Finnish language, led to the adoption of an expanded concept of Finland.[33]

History

Prehistory

If the archeological finds from Wolf Cave are the result of Neanderthals' activities, the first people inhabited Finland approximately 120,000–130,000 years ago.[36] The area that is now Finland was settled in, at the latest, around 8,500 BC during the Stone Age towards the end of the last glacial period. The artefacts the first settlers left behind present characteristics that are shared with those found in Estonia, Russia, and Norway.[37] The earliest people were hunter-gatherers, using stone tools.[38]

The first pottery appeared in 5200 BC, when the Comb Ceramic culture was introduced.[39] The arrival of the Corded Ware culture in Southern coastal Finland between 3000 and 2500 BC may have coincided with the start of agriculture.[40] Even with the introduction of agriculture, hunting and fishing continued to be important parts of the subsistence economy.

In the Bronze Age permanent all-year-round cultivation and animal husbandry spread, but the cold climate phase slowed the change.[41] Cultures in Finland shared common features in pottery and also axes had similarities but local features existed. The Seima-Turbino phenomenon brought the first bronze artefacts to the region and possibly also the Finno-Ugric languages.[41][42] Commercial contacts that had so far mostly been to Estonia started to extend to Scandinavia. Domestic manufacture of bronze artefacts started 1300 BC with Maaninka-type bronze axes. Bronze was imported from Volga region and from Southern Scandinavia.[43]

In the Iron Age population grew especially in Häme and Savo regions. Finland proper was the most densely populated area. Cultural contacts with the Baltics and Scandinavia became more frequent. Commercial contacts in the Baltic Sea region grew and extended during the eighth and ninth centuries.

Main exports from Finland were furs, slaves, castoreum, and falcons to European courts. Imports included silk and other fabrics, jewelry, Ulfberht swords, and, in lesser extent, glass. Production of iron started approximately in 500 BC.[44]

At the end of the ninth century, indigenous artefact culture, especially weapons and women's jewelry, had more common local features than ever before. This has been interpreted to be expressing common Finnish identity which was born from an image of common origin.[45]

An early form of Finnic languages spread to the Baltic Sea region approximately 1900 BC with the Seima-Turbino-phenomenon. Common Finnic language was spoken around Gulf of Finland 2000 years ago. The dialects from which the modern-day Finnish language was developed came into existence during the Iron Age.[46] Although distantly related, the Sami retained the hunter-gatherer lifestyle longer than the Finns. The Sami cultural identity and the Sami language have survived in Lapland, the northernmost province, but the Sami have been displaced or assimilated elsewhere.

The 12th and 13th centuries were a violent time in the northern Baltic Sea. The Livonian Crusade was ongoing and the Finnish tribes such as the Tavastians and Karelians were in frequent conflicts with Novgorod and with each other. Also, during the 12th and 13th centuries several crusades from the Catholic realms of the Baltic Sea area were made against the Finnish tribes. Danes waged at least three crusades to Finland, in 1187 or slightly earlier,[47] in 1191 and in 1202,[48] and Swedes, possibly the so-called second crusade to Finland, in 1249 against Tavastians and the third crusade to Finland in 1293 against the Karelians. The so-called first crusade to Finland, possibly in 1155, is most likely an unreal event. Also, it is possible that Germans made violent conversion of Finnish pagans in the 13th century.[49] According to a papal letter from 1241, the king of Norway was also fighting against "nearby pagans" at that time.[50]

Swedish era

_en2.png.webp)

Dark green: Sweden proper, as represented in the Riksdag of the Estates. Other greens: Swedish dominions and possessions

As a result of the crusades (mostly with the second crusade led by Birger Jarl) and the colonization of some Finnish coastal areas with Christian Swedish population during the Middle Ages,[51] including the old capital Turku, Finland gradually became part of the kingdom of Sweden and the sphere of influence of the Catholic Church. Due to the Swedish conquest, the Finnish upper class lost its position and lands to the new Swedish and German nobility and the Catholic Church.[52]

Swedish became the dominant language of the nobility, administration, and education; Finnish was chiefly a language for the peasantry, clergy, and local courts in predominantly Finnish-speaking areas. During the Protestant Reformation, the Finns gradually converted to Lutheranism.[53]

In the 16th century, a bishop and Lutheran Reformer Mikael Agricola published the first written works in Finnish, of which the first work, Abckiria, was published in 1543;[54] and Finland's current capital city, Helsinki, was founded by King Gustav Vasa in 1555.[55] The first university in Finland, the Royal Academy of Turku, was established by Queen Christina of Sweden at the proposal of Count Per Brahe in 1640.[56][57]

The Finns reaped a reputation in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) as a well-trained cavalrymen called "Hakkapeliitta", that division excelled in sudden and savage attacks, raiding and reconnaissance, which King Gustavus Adolphus took advantage of in his significant battles, like in the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631) and the Battle of Rain (1632).[58][59] Finland suffered a severe famine in 1695–1697, during which about one third of the Finnish population died,[60] and a devastating plague a few years later.

In the 18th century, wars between Sweden and Russia twice led to the occupation of Finland by Russian forces, times known to the Finns as the Greater Wrath (1714–1721) and the Lesser Wrath (1742–1743).[61][60] It is estimated that almost an entire generation of young men was lost during the Great Wrath, due mainly to the destruction of homes and farms, and the burning of Helsinki.

Two Russo-Swedish wars in twenty-five years served as reminders to the Finnish people of the precarious position between Sweden and Russia.[61] An increasingly vocal elite in Finland soon determined that Finnish ties with Sweden were becoming too costly, and following the Russo-Swedish War (1788–1790), the Finnish elite's desire to break with Sweden only heightened.[63] Even before the war there were conspiring politicians, among them Georg Magnus Sprengtporten, who had supported Gustav III's coup in 1772. Sprengtporten fell out with the king and resigned his commission in 1777. In the following decade he tried to secure Russian support for an autonomous Finland, and later became an adviser to Catherine II.[63] In the spirit of the notion of Adolf Ivar Arwidsson (1791–1858) – "we are not Swedes, we do not want to become Russians, let us, therefore, be Finns" – a Finnish national identity started to become established.[64] Notwithstanding the efforts of Finland's elite and nobility to break ties with Sweden, there was no genuine independence movement in Finland until the early 20th century.[63] The Swedish era ended in the Finnish War in 1809.

Russian era

On 29 March 1809, having been taken over by the armies of Alexander I of Russia in the Finnish War, Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire with the recognition given at the Diet held in Porvoo. This situation lasted until the end of 1917.[61] In 1812, Alexander I incorporated the Russian Vyborg province into the Grand Duchy of Finland. In 1854, Finland became involved in Russia's involvement in the Crimean War, when the British and French navies bombed the Finnish coast and Åland during the so-called Åland War. During the Russian era, the Finnish language began to gain recognition. From the 1860s onwards, a strong Finnish nationalist movement known as the Fennoman movement grew, and one of its most prominent leading figures of the movement was the philosopher J. V. Snellman, who was strictly inclined to Hegel's idealism, and who pushed for the stabilization of the status of the Finnish language and its own currency, the Finnish markka, in the Grand Duchy of Finland.[65][66] Milestones included the publication of what would become Finland's national epic – the Kalevala – in 1835, and the Finnish language's achieving equal legal status with Swedish in 1892.

The Finnish famine of 1866–1868 occurred after a promisingly warm midsummer and freezing temperatures in early September ravaged crops,[67] and it killed approximately 15% of the population, making it one of the worst famines in European history. The famine led the Russian Empire to ease financial regulations, and investment rose in the following decades. Economic and political development was rapid.[68] The gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was still half of that of the United States and a third of that of Britain.[68]

From 1869 until 1917, the Russian Empire pursued a policy known as the "Russification of Finland". This policy was interrupted between 1905 and 1908. In 1906, universal suffrage was adopted in the Grand Duchy of Finland. However, the relationship between the Grand Duchy and the Russian Empire soured when the Russian government made moves to restrict Finnish autonomy. For example, universal suffrage was, in practice, virtually meaningless, since the tsar did not have to approve any of the laws adopted by the Finnish parliament. The desire for independence gained ground, first among radical liberals[69] and socialists, driven in part by a declaration called the February Manifesto by the last tsar of the Russian Empire, Nicholas II, on 15 February 1899.[70]

Civil war and early independence

After the 1917 February Revolution, the position of Finland as part of the Russian Empire was questioned, mainly by Social Democrats. Since the head of state was the tsar of Russia, it was not clear who the chief executive of Finland was after the revolution. The Parliament, controlled by social democrats, passed the so-called Power Act to give the highest authority to the Parliament. This was rejected by the Russian Provisional Government which decided to dissolve the Parliament.[71]

New elections were conducted, in which right-wing parties won with a slim majority. Some social democrats refused to accept the result and still claimed that the dissolution of the parliament (and thus the ensuing elections) were extralegal. The two nearly equally powerful political blocs, the right-wing parties, and the social-democratic party were highly antagonized.

The October Revolution in Russia changed the geopolitical situation once more. Suddenly, the right-wing parties in Finland started to reconsider their decision to block the transfer of the highest executive power from the Russian government to Finland, as the Bolsheviks took power in Russia. Rather than acknowledge the authority of the Power Act of a few months earlier, the right-wing government, led by Prime Minister P. E. Svinhufvud, presented Declaration of Independence on 4 December 1917, which was officially approved two days later, on 6 December, by the Finnish Parliament. The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), led by Vladimir Lenin, recognized independence on 4 January 1918.[72]

On 27 January 1918, the official opening shots of the civil war were fired in two simultaneous events: on the one hand, the government's beginning to disarm the Russian forces in Pohjanmaa, and on the other, a coup launched by the Social Democratic Party. The latter gained control of southern Finland and Helsinki, but the White government continued in exile from Vaasa.[73][74] This sparked the brief but bitter civil war. The Whites, who were supported by Imperial Germany, prevailed over the Reds,[75] which were guided by Kullervo Manner's desire to make the newly independent country a Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (also known as "Red Finland") and part of the RSFSR.[76] After the war, tens of thousands of Reds and suspected sympathizers were interned in camps, where thousands were executed or died from malnutrition and disease. Deep social and political enmity was sown between the Reds and Whites and would last until the Winter War and even beyond.[77][78] The civil war and the 1918–1920 activist expeditions called "Kinship Wars" into Soviet Russia strained Eastern relations. At that time, the idea of a Greater Finland also emerged for the first time.[79][80]

.jpg.webp)

After brief experimentation with monarchy, when an attempt to make Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse King of Finland was unsuccessful, Finland became a presidential republic, with K. J. Ståhlberg elected as its first president in 1919. As a liberal nationalist with a legal background, Ståhlberg anchored the state in liberal democracy, supported the rule of law, and embarked on internal reforms.[81] Finland was also one of the first European countries to strongly aim for equality for women, with Miina Sillanpää serving in Väinö Tanner's cabinet as the first female minister in Finnish history in 1926–1927.[82] The Finnish–Russian border was defined in 1920 by the Treaty of Tartu, largely following the historic border but granting Pechenga (Finnish: Petsamo) and its Barents Sea harbour to Finland.[61] Finnish democracy did not experience any Soviet coup attempts and likewise survived the anti-communist Lapua Movement.

In 1917, the population was three million. Credit-based land reform was enacted after the civil war, increasing the proportion of the capital-owning population.[68] About 70% of workers were occupied in agriculture and 10% in industry.[83] The largest export markets were the United Kingdom and Germany.

World War II and after

The Soviet Union launched the Winter War on 30 November 1939 in an effort to annex Finland.[84] The Finnish Democratic Republic was established by Joseph Stalin at the beginning of the war to govern Finland after Soviet conquest.[85] The Red Army was defeated in numerous battles, notably at the Battle of Suomussalmi. After two months of negligible progress on the battlefield, as well as severe losses of men and materiel, the Soviets put an end to the Finnish Democratic Republic in late January 1940 and recognized the legal Finnish government as the legitimate government of Finland.[86] Soviet forces began to make progress in February and reached Vyborg in March. The fighting came to an end on 13 March 1940 with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty. Finland had successfully defended its independence, but ceded 9% of its territory to the Soviet Union.

Hostilities resumed in June 1941 with the Continuation War, when Finland aligned with Germany following the latter's invasion of the Soviet Union; the primary aim was to recapture the territory lost to the Soviets scarcely one year before. For 872 days, the German army, aided indirectly by Finnish forces, besieged Leningrad, the USSR's second-largest city.[87] Finnish forces occupied East Karelia from 1941 to 1944. Finnish resistance to the Vyborg–Petrozavodsk offensive in the summer of 1944 led to a standstill, and the two sides reached an armistice. This was followed by the Lapland War of 1944–1945, when Finland fought retreating German forces in northern Finland. Famous war heroes of the aforementioned wars include Simo Häyhä,[88][89] Aarne Juutilainen,[90] and Lauri Törni.[91]

The treaties signed with the Soviet Union in 1947 and 1948 included Finnish obligations, restraints, and reparations, as well as further Finnish territorial concessions in addition to those in the Moscow Peace Treaty. As a result of the two wars, Finland ceded Petsamo, along with parts of Finnish Karelia and Salla; this amounted to 12% of Finland's land area, 20% of its industrial capacity, its second-largest city, Vyborg (Viipuri), and the ice-free port of Liinakhamari (Liinahamari). Almost the whole Finnish population, some 400,000 people, fled these areas. The former Finnish territory now constitutes part of Russia's Republic of Karelia, Leningrad Oblast, and Murmansk Oblast. Finland lost 97,000 soldiers and was forced to pay war reparations of $300 million ($5.5 billion in 2020); nevertheless, it avoided occupation by Soviet forces and managed to retain its independence.

Finland rejected Marshall aid, in apparent deference to Soviet desires. However, in the hope of preserving Finland's independence, the United States provided secret development aid and helped the Social Democratic Party.[92] Establishing trade with the Western powers, such as the United Kingdom, and paying reparations to the Soviet Union produced a transformation of Finland from a primarily agrarian economy to an industrialized one. Valmet (originally a shipyard, then several metal workshops) was founded to create materials for war reparations. After the reparations had been paid off, Finland continued to trade with the Soviet Union in the framework of bilateral trade.

In 1950, 46% of Finnish workers worked in agriculture and a third lived in urban areas.[93] The new jobs in manufacturing, services, and trade quickly attracted people to the towns. The average number of births per woman declined from a baby boom peak of 3.5 in 1947 to 1.5 in 1973.[93] When baby boomers entered the workforce, the economy did not generate jobs quickly enough, and hundreds of thousands emigrated to the more industrialized Sweden, with emigration peaking in 1969 and 1970.[93] The 1952 Summer Olympics brought international visitors. Finland took part in trade liberalization in the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet bloc during the Cold War. The military YYA Treaty (Finno-Soviet Pact of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance) gave the Soviet Union some leverage in Finnish domestic politics. This was extensively exploited by president Urho Kekkonen against his opponents. He maintained an effective monopoly on Soviet relations from 1956 on, which was crucial for his continued popularity. In politics, there was a tendency to avoid any policies and statements that could be interpreted as anti-Soviet. This phenomenon was given the name "Finlandization" by the West German press.[94]

Finland maintained a market economy. Various industries benefited from trade privileges with the Soviets. Economic growth was rapid in the postwar era, and by 1975 Finland's GDP per capita was the 15th-highest in the world. In the 1970s and 1980s, Finland built one of the most extensive welfare states in the world. Finland negotiated with the European Economic Community (EEC, a predecessor of the European Union) a treaty that mostly abolished customs duties towards the EEC starting from 1977, although Finland did not fully join. In 1981, President Urho Kekkonen's failing health forced him to retire after holding office for 25 years.

Finland reacted cautiously to the collapse of the Soviet Union but swiftly began increasing integration with the West. On 21 September 1990, Finland unilaterally declared the Paris Peace Treaty obsolete, following the German reunification decision nine days earlier.[95]

Miscalculated macroeconomic decisions, a banking crisis, the collapse of its largest trading partner (the Soviet Union), and a global economic downturn caused a deep early 1990s recession in Finland. The depression bottomed out in 1993, and Finland saw steady economic growth for more than ten years.[96] Finland joined the European Union in 1995, and the Eurozone in 1999. Much of the late 1990s economic growth was fueled by the success of the mobile phone manufacturer Nokia, which held a unique position of representing 80% of the market capitalization of the Helsinki Stock Exchange.

21st century

.jpg.webp)

The Finnish population elected Tarja Halonen in the 2000 Presidential election, making her the first female President of Finland.[97] She held office throughout the decade. The country also received its first ever female Prime minister Anneli Jäätteenmäki in 2003, although she had to resign after only ten weeks holding the position due to the Iraq leak.[98][99] Financial crises also paralyzed Finland's exports in 2008, resulting in weaker economic growth throughout the decade.[100][101] Sauli Niinistö has subsequently been elected the President of Finland since 2012.[102]

Finland's support for NATO rose enormously after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[103][104][105] On 11 May 2022, Finland entered into a mutual security pact with the United Kingdom.[106] On 12 May, Finland's president and prime minister called for NATO membership "without delay".[107] Subsequently, on 17 May, the Parliament of Finland decided by a vote of 188–8 that it supported Finland's accession to NATO.[108][109] On 18 May the president and foreign minister submitted the application for membership.[110]

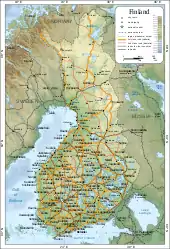

Geography

Lying approximately between latitudes 60° and 70° N, and longitudes 20° and 32° E, Finland is one of the world's northernmost countries. Of world capitals, only Reykjavík lies more to the north than Helsinki. The distance from the southernmost point – Hanko in Uusimaa – to the northernmost – Nuorgam in Lapland – is 1,160 kilometres (720 mi).

Finland has about 168,000 lakes (of area larger than 500 m2 or 0.12 acres) and 179,000 islands.[111] Its largest lake, Saimaa, is the fourth largest in Europe. The Finnish Lakeland is the area with the most lakes in the country; many of the major cities in the area, most notably Tampere, Jyväskylä and Kuopio, are located near the large lakes. The greatest concentration of islands is found in the southwest, in the Archipelago Sea between continental Finland and the main island of Åland.

Much of the geography of Finland is a result of the Ice Age. The glaciers were thicker and lasted longer in Fennoscandia compared with the rest of Europe. Their eroding effects have left the Finnish landscape mostly flat with few hills and fewer mountains. Its highest point, the Halti at 1,324 metres (4,344 ft), is found in the extreme north of Lapland at the border between Finland and Norway. The highest mountain whose peak is entirely in Finland is Ridnitšohkka at 1,316 m (4,318 ft), directly adjacent to Halti.

The retreating glaciers have left the land with morainic deposits in formations of eskers. These are ridges of stratified gravel and sand, running northwest to southeast, where the ancient edge of the glacier once lay. Among the biggest of these are the three Salpausselkä ridges that run across southern Finland.

Having been compressed under the enormous weight of the glaciers, terrain in Finland is rising due to the post-glacial rebound. The effect is strongest around the Gulf of Bothnia, where land steadily rises about 1 cm (0.4 in) a year. As a result, the old sea bottom turns little by little into dry land: the surface area of the country is expanding by about 7 square kilometres (2.7 sq mi) annually.[112] Relatively speaking, Finland is rising from the sea.[113]

The landscape is covered mostly by coniferous taiga forests and fens, with little cultivated land. Of the total area, 10% is lakes, rivers, and ponds, and 78% is forest. The forest consists of pine, spruce, birch, and other species.[114] Finland is the largest producer of wood in Europe and among the largest in the world. The most common type of rock is granite. It is a ubiquitous part of the scenery, visible wherever there is no soil cover. Moraine or till is the most common type of soil, covered by a thin layer of humus of biological origin. Podzol profile development is seen in most forest soils except where drainage is poor. Gleysols and peat bogs occupy poorly drained areas.

Biodiversity

Phytogeographically, Finland is shared between the Arctic, central European, and northern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Finland can be subdivided into three ecoregions: the Scandinavian and Russian taiga, Sarmatic mixed forests, and Scandinavian Montane Birch forest and grasslands.[115] Taiga covers most of Finland from northern regions of southern provinces to the north of Lapland. On the southwestern coast, south of the Helsinki-Rauma line, forests are characterized by mixed forests, that are more typical in the Baltic region. In the extreme north of Finland, near the tree line and Arctic Ocean, Montane Birch forests are common. Finland had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.08/10, ranking it 109th globally out of 172 countries.[116]

Similarly, Finland has a diverse and extensive range of fauna. There are at least sixty native mammalian species, 248 breeding bird species, over 70 fish species, and 11 reptile and frog species present today, many migrating from neighbouring countries thousands of years ago. Large and widely recognized wildlife mammals found in Finland are the brown bear, grey wolf, wolverine, and elk. The brown bear, which is also nicknamed as the "king of the forest" by the Finns, is the country's official national animal,[117] which also occur on the coat of arms of the Satakunta region is a crown-headed black bear carrying a sword,[118] possibly referring to the regional capital city of Pori, whose Swedish name Björneborg and the Latin name Arctopolis literally means "bear city" or "bear fortress".[119] Three of the more striking birds are the whooper swan, a large European swan and the national bird of Finland; the Western capercaillie, a large, black-plumaged member of the grouse family; and the Eurasian eagle-owl. The latter is considered an indicator of old-growth forest connectivity, and has been declining because of landscape fragmentation.[120] Around 24,000 species of Insects are prevalent in Finland some of the most common being hornets with tribes of beetles such as the Onciderini also being common. The most common breeding birds are the willow warbler, common chaffinch, and redwing.[121] Of some seventy species of freshwater fish, the northern pike, perch, and others are plentiful. Atlantic salmon remains the favourite of fly rod enthusiasts.

The endangered Saimaa ringed seal (Pusa hispida saimensis), one of only three lake seal species in the world, exists only in the Saimaa lake system of southeastern Finland, down to only 390 seals today.[122] Ever since the species was protected in 1955,[123] it has become the emblem of the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation.[124] The Saimaa ringed seal lives nowadays mainly in two Finnish national parks, Kolovesi and Linnansaari,[125] but strays have been seen in a much larger area, including near Savonlinna's town centre.

A third of Finland's land area originally consisted of moorland, about half of this area has been drained for cultivation over the past centuries.[126]

Climate

The main factor influencing Finland's climate is the country's geographical position between the 60th and 70th northern parallels in the Eurasian continent's coastal zone. In the Köppen climate classification, the whole of Finland lies in the boreal zone, characterized by warm summers and freezing winters. Within the country, the temperateness varies considerably between the southern coastal regions and the extreme north, showing characteristics of both a maritime and a continental climate. Finland is near enough to the Atlantic Ocean to be continuously warmed by the Gulf Stream. The Gulf Stream combines with the moderating effects of the Baltic Sea and numerous inland lakes to explain the unusually warm climate compared with other regions that share the same latitude, such as Alaska, Siberia, and southern Greenland.[127]

Winters in southern Finland (when mean daily temperature remains below 0 °C or 32 °F) are usually about 100 days long, and in the inland the snow typically covers the land from about late November to April, and on the coastal areas such as Helsinki, snow often covers the land from late December to late March.[128] Even in the south, the harshest winter nights can see the temperatures fall to −30 °C (−22 °F) although on coastal areas like Helsinki, temperatures below −30 °C (−22 °F) are rare. Climatic summers (when mean daily temperature remains above 10 °C or 50 °F) in southern Finland last from about late May to mid-September, and in the inland, the warmest days of July can reach over 35 °C (95 °F).[127] Although most of Finland lies on the taiga belt, the southernmost coastal regions are sometimes classified as hemiboreal.[129]

In northern Finland, particularly in Lapland, the winters are long and cold, while the summers are relatively warm but short. On the most severe winter days in Lapland can see the temperature fall to −45 °C (−49 °F). The winter of the north lasts for about 200 days with permanent snow cover from about mid-October to early May. Summers in the north are quite short, only two to three months, but can still see maximum daily temperatures above 25 °C (77 °F) during heat waves.[127] No part of Finland has Arctic tundra, but Alpine tundra can be found at the fells Lapland.[129]

The Finnish climate is suitable for cereal farming only in the southernmost regions, while the northern regions are suitable for animal husbandry.[130]

A quarter of Finland's territory lies within the Arctic Circle and the midnight sun can be experienced for more days the farther north one travels. At Finland's northernmost point, the sun does not set for 73 consecutive days during summer and does not rise at all for 51 days during winter.[127]

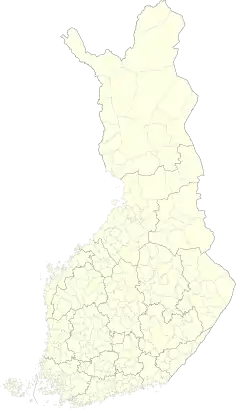

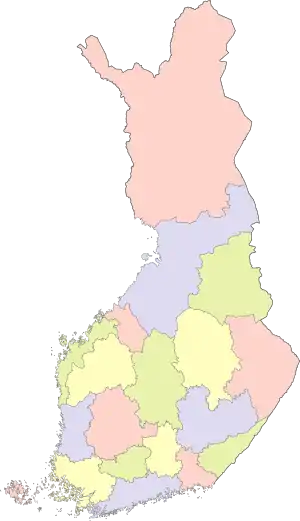

Regions

Finland consists of 19 regions, called maakunta in Finnish and landskap in Swedish. The counties are governed by regional councils which serve as forums of cooperation for the municipalities of a county. The main tasks of the counties are regional planning and development of enterprise and education. In addition, the public health services are usually organized based on counties. Currently, the only county where a popular election is held for the council is Kainuu. Other regional councils are elected by municipal councils, each municipality sending representatives in proportion to its population.

In addition to inter-municipal cooperation, which is the responsibility of regional councils, each county has a state Employment and Economic Development Centre which is responsible for the local administration of labour, agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and entrepreneurial affairs. The Finnish Defence Forces regional offices are responsible for the regional defence preparations and the administration of conscription within the county.

Counties represent dialectal, cultural, and economic variations better than the former provinces, which were purely administrative divisions of the central government. Historically, counties are divisions of historical provinces of Finland, areas that represent dialects and culture more accurately.

Six Regional State Administrative Agencies were created by the state of Finland in 2010, each of them responsible for one of the counties called alue in Finnish and region in Swedish; in addition, Åland was designated a seventh county. These take over some of the tasks of the earlier Provinces of Finland (lääni/län), which were abolished.[131]

|

The county of Eastern Uusimaa (Itä-Uusimaa) was consolidated with Uusimaa on 1 January 2011.[134]

Administrative divisions

The fundamental administrative divisions of the country are the municipalities, which may also call themselves towns or cities. They account for half of the public spending. Spending is financed by municipal income tax, state subsidies, and other revenue. As of 2021, there are 309 municipalities,[135] and most have fewer than 6,000 residents.

In addition to municipalities, two intermediate levels are defined. Municipalities co-operate in seventy sub-regions and nineteen counties. These are governed by the member municipalities and have only limited powers. The autonomous province of Åland has a permanent democratically elected regional council. Sami people have a semi-autonomous Sami native region in Lapland for issues on language and culture.

In the following chart, the number of inhabitants includes those living in the entire municipality (kunta/kommun), not just in the built-up area. The land area is given in km2, and the density in inhabitants per km2 (land area). The figures are as of 31 December 2021. The capital region – comprising Helsinki, Vantaa, Espoo and Kauniainen – forms a continuous conurbation of over 1.1 million people. However, common administration is limited to voluntary cooperation of all municipalities, e.g. in Helsinki Metropolitan Area Council.

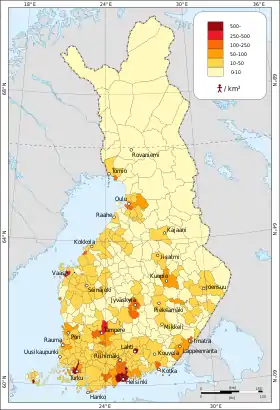

| City | Population[136] | Land area[137] | Density | Regional map | Population density map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 658,864 | 213.75 | 3,082.4 |

Municipalities (thin borders) and counties (thick borders) of Finland (2021) |

The population densities of Finnish municipalities (2010) | |

| 297,354 | 312.26 | 952.26 | |||

| 244,315 | 525.03 | 465.34 | |||

| 239,216 | 238.37 | 1,003.55 | |||

| 209,648 | 1,410.17 | 148.67 | |||

| 195,301 | 245.67 | 794.97 | |||

| 144,477 | 1,170.99 | 123.38 | |||

| 121,557 | 1,597.39 | 76.1 | |||

| 120,093 | 459.47 | 261.37 | |||

| 83,491 | 834.06 | 100.1 | |||

| 80,483 | 2,558.24 | 31.46 | |||

| 77,266 | 2,381.76 | 32.44 | |||

| 72,646 | 1,433.36 | 50.68 | |||

| 67,994 | 1,785.76 | 38.08 | |||

| 67,631 | 188.81 | 358.2 |

Government and politics

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Constitution

The Constitution of Finland defines the political system; Finland is a parliamentary republic within the framework of a representative democracy. The Prime Minister is the country's most powerful person. The current version of the constitution was enacted on 1 March 2000 and was amended on 1 March 2012. Citizens can run and vote in parliamentary, municipal, presidential, and European Union elections.

President

Finland's head of state is the President of the Republic (in Finnish: Suomen tasavallan presidentti; in Swedish: Republiken Finlands president). Finland has had for most of its independence a semi-presidential system of government, but in the last few decades the powers of the President have been diminished, and the country is now considered a parliamentary republic.[4] Constitutional amendments which came into effect in 1991 and 1992, as well as a new constitution enacted in 2000 (subsequently amended in 2012), have made the presidency a primarily ceremonial office that appoints the Prime Minister as elected by Parliament, appoints and dismisses the other ministers of the Finnish Government on the recommendation of the Prime Minister, opens parliamentary sessions, and confers state honors. Nevertheless, the President remains responsible for Finland's foreign relations, including the making of war and peace, but excluding matters related to the European Union. Moreover, the President exercises supreme command over the Finnish Defence Forces as commander-in-chief. In the exercise of his or her foreign and defense powers, the President is required to consult the Finnish Government, but the Government's advice is not binding. In addition, the President has several domestic reserve powers, including the authority to veto legislation, to grant pardons, and to appoint several public officials, such as Finnish ambassadors and heads of diplomatic missions, the Director-General of Kela, the Chancellor of Justice, the Prosecutor General, and the Governor and Board of the Bank of Finland, among others. The President is also required by the Constitution to dismiss individual ministers or the entire Government upon a parliamentary vote of no confidence. In summary, the President serves as a guardian of Finnish democracy and sovereignty at home and abroad.[138]

The President is directly elected via runoff voting for a maximum of two consecutive 6-year terms. The current president is Sauli Niinistö; he took office on 1 March 2012. Former presidents were K. J. Ståhlberg (1919–1925), L. K. Relander (1925–1931), P. E. Svinhufvud (1931–1937), Kyösti Kallio (1937–1940), Risto Ryti (1940–1944), C. G. E. Mannerheim (1944–1946), J. K. Paasikivi (1946–1956), Urho Kekkonen (1956–1982), Mauno Koivisto (1982–1994), Martti Ahtisaari (1994–2000), and Tarja Halonen (2000–2012). Niinistö's election as a member of the National Coalition Party marks the first time since 1946 that a Finnish President is not a member of either the Social Democratic Party or the Centre Party.

Parliament

The 200-member unicameral Parliament of Finland (Finnish: Eduskunta, Swedish: Riksdag) exercises supreme legislative authority in the country. It may alter the constitution and ordinary laws, dismiss the cabinet, and override presidential vetoes. Its acts are not subject to judicial review; the constitutionality of new laws is assessed by the parliament's constitutional law committee. The parliament is elected for a term of four years using the proportional D'Hondt method within several multi-seat constituencies through the most open list multi-member districts. Various parliament committees listen to experts and prepare legislation.

Since universal suffrage was introduced in 1906, the parliament has been dominated by the Centre Party (former Agrarian Union), the National Coalition Party, and the Social Democrats. These parties have enjoyed approximately equal support, and their combined vote has totalled about 65–80% of all votes. For a few decades after 1944, the Communists were a strong fourth party. The relative strengths of the parties have commonly varied only slightly from one election to another. However, there have been some long-term trends, such as the rise and fall of the Communists during the Cold War; the steady decline into insignificance of the Liberals and their predecessors from 1906 to 1980; and the rise of the Green League since 1983.

The Marin Cabinet is the incumbent 76th government of Finland. It took office on 10 December 2019.[139][140] The cabinet consists of a coalition formed by the Social Democratic Party, the Centre Party, the Green League, the Left Alliance, and the Swedish People's Party.[141]

Cabinet

After parliamentary elections, the parties negotiate among themselves on forming a new cabinet (the Finnish Government), which then has to be approved by a simple majority vote in the parliament. The cabinet can be dismissed by a parliamentary vote of no confidence, although this rarely happens (the last time in 1957), as the parties represented in the cabinet usually make up a majority in the parliament.[142]

The cabinet exercises most executive powers and originates most of the bills that the parliament then debates and votes on. It is headed by the Prime Minister of Finland, and consists of him or her, other ministers, and the Chancellor of Justice. The current prime minister is Sanna Marin (Social Democratic Party). Each minister heads his or her ministry, or, in some cases, has responsibility for a subset of a ministry's policy. After the prime minister, the most powerful minister is often the minister of finance.

As no one party ever dominates the parliament, Finnish cabinets are multi-party coalitions. As a rule, the post of prime minister goes to the leader of the biggest party and that of the minister of finance to the leader of the second biggest.

Law

The judicial system of Finland is a civil law system divided between courts with regular civil and criminal jurisdiction and administrative courts with jurisdiction over litigation between individuals and the public administration. Finnish law is codified and based on Swedish law and in a wider sense, civil law or Roman law. The court system for civil and criminal jurisdiction consists of local courts, regional appellate courts, and the Supreme Court. The administrative branch of justice consists of administrative courts and the Supreme Administrative Court. In addition to the regular courts, there are a few special courts in certain branches of administration. There is also a High Court of Impeachment for criminal charges against certain high-ranking officeholders.

Around 92% of residents have confidence in Finland's security institutions.[143] The overall crime rate of Finland is not high in the EU context. Some crime types are above average, notably the high homicide rate for Western Europe.[144] A day fine system is in effect and also applied to offenses such as speeding. Finland has a very low number of corruption charges; Transparency International ranks Finland as one of the least corrupt countries in Europe.

Foreign relations

According to the 2012 constitution, the president (currently Sauli Niinistö) leads foreign policy in cooperation with the government, except that the president has no role in EU affairs.[145]

In 2008, president Martti Ahtisaari was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[146] Finland was considered a cooperative model state, and Finland did not oppose proposals for a common EU defence policy.[147] This was reversed in the 2000s, when Tarja Halonen and Erkki Tuomioja made Finland's official policy to resist other EU members' plans for common defence.[147]

Military

The Finnish Defence Forces consist of a cadre of professional soldiers (mainly officers and technical personnel), currently serving conscripts, and a large reserve. The standard readiness strength is 34,700 people in uniform, of which 25% are professional soldiers. A universal male conscription is in place, under which all male Finnish nationals above 18 years of age serve for 6 to 12 months of armed service or 12 months of civilian (non-armed) service. Voluntary post-conscription overseas peacekeeping service is popular, and troops serve around the world in UN, NATO, and EU missions. Approximately 500 women choose voluntary military service every year.[148] Women are allowed to serve in all combat arms including front-line infantry and special forces. The army consists of a highly mobile field army backed up by local defence units. The army defends the national territory and its military strategy employs the use of the heavily forested terrain and numerous lakes to wear down an aggressor, instead of attempting to hold the attacking army on the frontier. With a high capability of military personnel,[149] arsenal[150] and homeland defence willingness, Finland is one of Europe's militarily strongest countries.[151]

Finnish defence expenditure per capita is one of the highest in the European Union.[152] The Finnish military doctrine is based on the concept of total defence. The term total means that all sectors of the government and economy are involved in the defence planning. The armed forces are under the command of the Chief of Defence (currently General Jarmo Lindberg), who is directly subordinate to the president in matters related to military command. The branches of the military are the army, the navy, and the air force. The border guard is under the Ministry of the Interior but can be incorporated into the Defence Forces when required for defence readiness.

Even while Finland hasn't joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the country has joined the NATO Response Force, the EU Battlegroup,[153] the NATO Partnership for Peace and in 2014 signed a NATO memorandum of understanding,[154][155] thus forming a practical coalition.[18] In 2015, the Finland-NATO ties were strengthened with a host nation support agreement allowing assistance from NATO troops in emergency situations.[156] Finland has been an active participant in the Afghanistan and Kosovo wars.[157][158]

Social security

Finland has one of the world's most extensive welfare systems, one that guarantees decent living conditions for all residents: Finns, and non-citizens. Since the 1980s social security has been cut back, but still the system is one of the most comprehensive in the world. Created almost entirely during the first three decades after World War II, the social security system was an outgrowth of the traditional Nordic belief that the state was not inherently hostile to the well-being of its citizens but could intervene benevolently on their behalf. According to some social historians, the basis of this belief was a relatively benign history that had allowed the gradual emergence of free and independent farmers in the Nordic countries and had curtailed the dominance of the nobility and the subsequent formation of a powerful right-wing. Finland's history has been harsher than the histories of the other Nordic countries, but not harsh enough to bar the country from following its path of social development.[159]

Human rights

.jpg.webp)

§ 6 in two sentences of the Finnish Constitution states: "No one shall be placed in a different position on situation of sex, age, origin, language, religion, belief, opinion, state of health, disability or any other personal reason without an acceptable reason."[160]

Finland has been ranked above average among the world's countries in democracy,[161] press freedom,[162] and human development.[163] Amnesty International has expressed concern regarding some issues in Finland, such as the imprisonment of conscientious objectors, and societal discrimination against Romani people and members of other ethnic and linguistic minorities.[164][165]

Economy

The economy of Finland has a per capita output equal to that of other European economies such as those of France, Germany, Belgium, or the UK. The largest sector of the economy is the service sector at 66% of GDP, followed by manufacturing and refining at 31%. Primary production represents 2.9%.[166] With respect to foreign trade, the key economic sector is manufacturing. The largest industries in 2007[167] were electronics (22%); machinery, vehicles, and other engineered metal products (21.1%); forest industry (13%); and chemicals (11%). The gross domestic product peaked in 2008. As of 2015, the country's economy is at the 2006 level.[168][169] Finland is ranked as the 7th most innovative country in the Global Innovation Index in 2021.[170]

Finland has significant timber, mineral (iron, chromium, copper, nickel, and gold), and freshwater resources. Forestry, paper factories, and the agricultural sector are important for rural residents. The Greater Helsinki area generates around one-third of Finland's GDP. Private services are the largest employer in Finland.

Finland's climate and soils make growing crops a particular challenge. The country lies between the latitudes 60°N and 70°N, and it has severe winters and relatively short growing seasons that are sometimes interrupted by frost. However, because the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Drift Current moderate the climate, Finland contains half of the world's arable land north of 60° north latitude. Annual precipitation is usually sufficient, but it occurs almost exclusively during the winter months, making summer droughts a constant threat. In response to the climate, farmers have relied on quick-ripening and frost-resistant varieties of crops, and they have cultivated south-facing slopes as well as richer bottomlands to ensure production even in years with summer frosts. Most farmland was originally either forest or swamp, and the soil has usually required treatment with lime and years of cultivation to neutralize the excess acid and to improve fertility. Irrigation has generally not been necessary, but drainage systems are often needed to remove excess water. Finland's agriculture has been efficient and productive—at least when compared with farming in other European countries.[159]

Forests play a key role in the country's economy, making it one of the world's leading wood producers and providing raw materials at competitive prices for the crucial wood processing industries. As in agriculture, the government has long played a leading role in forestry, regulating tree cutting, sponsoring technical improvements, and establishing long-term plans to ensure that the country's forests continue to supply the wood-processing industries.[159]

As of 2008, average purchasing power-adjusted income levels are similar to those of Italy, Sweden, Germany, and France.[171] In 2006, 62% of the workforce worked for enterprises with less than 250 employees and they accounted for 49% of total business turnover.[172] The female employment rate is high. Gender segregation between male-dominated professions and female-dominated professions is higher than in the US.[173] The proportion of part-time workers was one of the lowest in OECD in 1999.[173] In 2013, the 10 largest private sector employers in Finland were Itella, Nokia, OP-Pohjola, ISS, VR, Kesko, UPM-Kymmene, YIT, Metso, and Nordea.[174] The unemployment rate was 6.8% in 2022.[175]

As of 2006, 2.4 million households reside in Finland. The average size is 2.1 persons; 40% of households consist of a single person, 32% two persons and 28% three or more persons. Residential buildings total 1.2 million, and the average residential space is 38 square metres (410 sq ft) per person. The average residential property without land costs €1,187 per sq metre and residential land €8.60 per sq metre. 74% of households had a car. There are 2.5 million cars and 0.4 million other vehicles.[176]

The average total household consumption was €20,000, out of which housing consisted of about €5,500, transport about €3,000, food and beverages (excluding alcoholic beverages) at around €2,500, and recreation and culture at around €2,000.[177] In 2017, Finland's GDP reached €224 billion.[178]

Finland has the highest concentration of cooperatives relative to its population.[179] The largest retailer, which is also the largest private employer, S-Group, and the largest bank, OP-Group, in the country are both cooperatives.

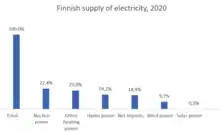

Energy

The free and largely privately owned financial and physical Nordic energy markets traded in NASDAQ OMX Commodities Europe and Nord Pool Spot exchanges, have provided competitive prices compared with other EU countries. As of 2007, Finland has roughly the lowest industrial electricity prices in the EU-15 (equal to France).[181]

In 2006, the energy market was around 90 terawatt hours and the peak demand around 15 gigawatts in winter. This means that the energy consumption per capita is around 7.2 tons of oil equivalent per year. Industry and construction consumed 51% of total consumption, a relatively high figure reflecting Finland's industries.[182][183] Finland's hydrocarbon resources are limited to peat and wood. About 10–15% of the electricity is produced by hydropower,[184] which is low compared with more mountainous Sweden or Norway. In 2008, renewable energy (mainly hydropower and various forms of wood energy) was high at 31% compared with the EU average of 10.3% in final energy consumption.[185] Finland is a member of the International Energy Agency and, as such, maintains a strategic petroleum reserve in the case of emergencies. As of February 2022, Finland's reserves held 200 days worth of net oil imports.[186]

Finland has four privately owned nuclear reactors producing 18% of the country's energy[188] at the Otaniemi campus. The fifth AREVA-Siemens-built reactor – the world's largest at 1600 MWe and a focal point of Europe's nuclear industry – has faced many delays and is currently scheduled to be operational by June 2022, over 12 years after the original planned opening.[189] A varying amount (5–17%) of electricity has been imported from Russia (at around 3-gigawatt power line capacity), Sweden and Norway.

The Onkalo spent nuclear fuel repository is currently under construction at the Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant in the municipality of Eurajoki, on the west coast of Finland, by the company Posiva.[190] The start of commercial operations for the completed reactor in Finland can lead to an increase of up to 20 TWh in EU nuclear power generation in 2022.[191]

Transport

Finland's road system is utilized by most internal cargo and passenger traffic. The annual state operated road network expenditure of around €1 billion is paid for with vehicle and fuel taxes which amount to around €1.5 billion and €1 billion, respectively. Among the Finnish highways, the most significant and busiest main roads include the Turku Highway (E18), the Tampere Highway (E12), the Lahti Highway (E75), and the ring roads (Ring I and Ring III) of the Helsinki metropolitan area and the Tampere Ring Road of the Tampere urban area.[192]

The main international passenger gateway is Helsinki Airport, which handled about 21 million passengers in 2019 (5 million in 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic). Oulu Airport is the second largest with 1 million passengers in 2019 (300,000 in 2020), whilst another 25 airports have scheduled passenger services. The Helsinki Airport-based Finnair, Blue1, and Nordic Regional Airlines, Norwegian Air Shuttle sell air services both domestically and internationally. Helsinki has an optimal location for great circle (i.e. the shortest and most efficient) routes between Western Europe and the Far East.

The Government annually spends around €350 million to maintain the 5,865-kilometre-long (3,644 mi) network of railway tracks. Rail transport is handled by the state-owned VR Group, which has a 5% passenger market share (out of which 80% are from urban trips in Greater Helsinki) and 25% cargo market share.[194] Finland's first railway was opened between Helsinki and Hämeenlinna in 1862,[195][196] and today it forms part of the Finnish Main Line, which is more than 800 kilometers long. Helsinki opened the world's northernmost metro system in 1982.

The majority of international cargo shipments are handled at ports. Vuosaari Harbour in Helsinki is the largest container port in Finland; others include Kotka, Hamina, Hanko, Pori, Rauma, and Oulu. There is passenger traffic from Helsinki and Turku, which have ferry connections to Tallinn, Mariehamn, Stockholm and Travemünde. The Helsinki-Tallinn route is one of the busiest passenger sea routes in the world.[197]

Industry

Finland rapidly industrialized after World War II, achieving GDP per capita levels comparable to that of Japan or the UK at the beginning of the 1970s. Initially, most of the economic development was based on two broad groups of export-led industries, the "metal industry" (metalliteollisuus) and "forest industry" (metsäteollisuus). The "metal industry" includes shipbuilding, metalworking, the automotive industry, engineered products such as motors and electronics, and production of metals and alloys including steel, copper and chromium. Many of the world's biggest cruise ships, including MS Freedom of the Seas and the Oasis of the Seas have been built in Finnish shipyards.[198] [199] The "forest industry" includes forestry, timber, pulp and paper, and is often considered a logical development based on Finland's extensive forest resources, as 73% of the area is covered by forest. In the pulp and paper industry, many major companies are based in Finland; Ahlstrom-Munksjö, Metsä Board, and UPM are all Finnish forest-based companies with revenues exceeding €1 billion. However, in recent decades, the Finnish economy has diversified, with companies expanding into fields such as electronics (Nokia), metrology (Vaisala), petroleum (Neste), and video games (Rovio Entertainment), and is no longer dominated by the two sectors of metal and forest industry. Likewise, the structure has changed, with the service sector growing, with manufacturing declining in importance; agriculture remains a minor part. Despite this, production for export is still more prominent than in Western Europe, thus making Finland possibly more vulnerable to global economic trends.

In 2017, the Finnish economy was estimated to consist of approximately 2.7% agriculture, 28.2% manufacturing, and 69.1% services.[200] In 2019, the per-capita income of Finland was estimated to be $48,869. In 2020, Finland was ranked 20th on the ease of doing business index, among 190 jurisdictions.

Public policy

Finnish politicians have often emulated the Nordic model.[201] Nordics have been free-trading and relatively welcoming to skilled migrants for over a century, though in Finland immigration is relatively new. The level of protection in commodity trade has been low, except for agricultural products.[201]

Finland has top levels of economic freedom in many areas. Finland is ranked 16th in the 2008 global Index of Economic Freedom and ninth in Europe.[202] While the manufacturing sector is thriving, the OECD points out that the service sector would benefit substantially from policy improvements.[203]

The 2007 IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook ranked Finland 17th most competitive.[204] The World Economic Forum 2008 index ranked Finland the sixth most competitive.[205] In both indicators, Finland's performance was next to Germany, and significantly higher than most European countries. In the Business competitiveness index 2007–2008 Finland ranked third in the world.

Economists attribute much growth to reforms in the product markets. According to the OECD, only four EU-15 countries have less regulated product markets (UK, Ireland, Denmark and Sweden) and only one has less regulated financial markets (Denmark). Nordic countries were pioneers in liberalizing energy, postal, and other markets in Europe.[201] The legal system is clear and business bureaucracy less than most countries.[202] Property rights are well protected and contractual agreements are strictly honoured.[202] Finland is rated the least corrupt country in the world in the Corruption Perceptions Index[206] and 13th in the Ease of doing business index. This indicates exceptional ease in cross-border trading (5th), contract enforcement (7th), business closure (5th), tax payment (83rd), and low worker hardship (127th).[207]

In Finland, collective labour agreements are universally valid. These are drafted every few years for each profession and seniority level, with only a few jobs outside the system. The agreement becomes universally enforceable provided that more than 50% of the employees support it, in practice by being a member of a relevant trade union. The unionization rate is high (70%), especially in the middle class (AKAVA, mostly for university-educated professionals: 80%).[201]

Tourism

In 2017, tourism in Finland grossed approximately €15.0 billion with a 7% increase from the previous year. Of this, €4.6 billion (30%) came from foreign tourism.[212] In 2017, there were 15.2 million overnight stays of domestic tourists and 6.7 million overnight stays of foreign tourists.[213] Much of the sudden growth can be attributed to the globalization of the country as well as a rise in positive publicity and awareness. While Russia remains the largest market for foreign tourists, the biggest growth came from Chinese markets (35%).[213] Tourism contributes roughly 2.7% to Finland's GDP, making it comparable to agriculture and forestry.[214]

Commercial cruises between major coastal and port cities in the Baltic region, including Helsinki, Turku, Mariehamn, Tallinn, Stockholm, and Travemünde, play a significant role in the local tourism industry. There are also separate ferry connections dedicated to tourism in the vicinity of Helsinki and its region, such as the connection to the fortress island of Suomenlinna[215] or the connection to the old town of Porvoo.[216] By passenger counts, the Port of Helsinki is the busiest port in the world after the Port of Dover in the United Kingdom and the Port of Tallinn in Estonia.[217] The Helsinki-Vantaa International Airport is the fourth busiest airport in the Nordic countries in terms of passenger numbers,[218] and about 90% of Finland's international air traffic passes through the airport.[219]

Lapland has the highest tourism consumption of any Finnish region.[214] Above the Arctic Circle, in midwinter, there is a polar night, a period when the sun does not rise for days or weeks, or even months, and correspondingly, midnight sun in the summer, with no sunset even at midnight (for up to 73 consecutive days, at the northernmost point). Lapland is so far north that the aurora borealis, fluorescence in the high atmosphere due to solar wind, is seen regularly in the fall, winter, and spring. Finnish Lapland is also locally regarded as the home of Saint Nicholas or Santa Claus, with several theme parks, such as Santa Claus Village and Santa Park in Rovaniemi.[220] Other significant tourist destinations in Lapland also include ski resorts (such as Levi, Ruka and Ylläs)[221] and sleigh rides led by either reindeer or huskies.[222][223]

Tourist attractions in Finland include the natural landscape found throughout the country as well as urban attractions. Finland is covered with thick pine forests, rolling hills, and lakes. Finland contains 40 national parks (such as the Koli National Park in North Karelia), from the Southern shores of the Gulf of Finland to the high fells of Lapland. Outdoor activities range from Nordic skiing, golf, fishing, yachting, lake cruises, hiking, and kayaking, among many others. Bird-watching is popular for those fond of avifauna, however, hunting is also popular. Elk and hare are common game in Finland.

Finland also has urbanized regions with many cultural events and activities. The most famous tourist attractions in Helsinki include the Helsinki Cathedral and the Suomenlinna sea fortress. The most well-known Finnish amusement parks include Linnanmäki in Helsinki, Särkänniemi in Tampere, PowerPark in Kauhava, Tykkimäki in Kouvola and Nokkakivi in Laukaa.[224] St. Olaf's Castle (Olavinlinna) in Savonlinna hosts the annual Savonlinna Opera Festival,[225] and the medieval milieus of the cities of Turku, Rauma and Porvoo also attract curious spectators.[226]

Demographics

The population of Finland is currently about 5.5 million. The current birth rate is 10.42 per 1,000 residents, for a fertility rate of 1.49 children born per woman,[227] one of the lowest in the world, significantly below the replacement rate of 2.1. In 1887 Finland recorded its highest rate, 5.17 children born per woman.[228] Finland has one of the oldest populations in the world, with a median age of 42.6 years.[229] Approximately half of voters are estimated to be over 50 years old.[230][93][231][232] Finland has an average population density of 18 inhabitants per square kilometre. This is the third-lowest population density of any European country, behind those of Norway and Iceland, and the lowest population density of any European Union member country. Finland's population has always been concentrated in the southern parts of the country, a phenomenon that became even more pronounced during 20th-century urbanization. Two of the three largest cities in Finland are situated in the Greater Helsinki metropolitan area—Helsinki and Espoo, and some municipalities in the metropolitan area have also shown clear growth of population year after year, the most notable being Järvenpää, Nurmijärvi, Kirkkonummi, Kerava and Sipoo.[233] In the largest cities of Finland, Tampere holds the third place after Helsinki and Espoo while also Helsinki-neighbouring Vantaa is the fourth. Other cities with population over 100,000 are Turku, Oulu, Jyväskylä, Kuopio, and Lahti. On the other hand, Sottunga of Åland is the smallest municipality in Finland in terms of population (Luhanka in mainland Finland),[234] and Savukoski of Lapland is sparsely populated in terms of population density.[235]

As of 2021, there were 469,633 people with a foreign background living in Finland (8.5% of the population), most of whom are from the former Soviet Union, Estonia, Somalia, Iraq and former Yugoslavia.[236][237] The children of foreigners are not automatically given Finnish citizenship, as Finnish nationality law practices and maintain jus sanguinis policy where only children born to at least one Finnish parent are granted citizenship. If they are born in Finland and cannot get citizenship of any other country, they become citizens.[238] Additionally, certain persons of Finnish descent who reside in countries that were once part of Soviet Union, retain the right of return, a right to establish permanent residency in the country, which would eventually entitle them to qualify for citizenship.[239] 442,290 people in Finland in 2021 were born in another country, representing 8% of the population. The 10 largest foreign born groups are (in order) from Russia, Estonia, Sweden, Iraq, China, Somalia, Thailand, Vietnam, Serbia and India, with Turkey dropping to 11th place from last year.[240]

Finland's immigrant population is growing. By 2035, the three largest cities in Finland are projected to have over a quarter of residents of a foreign-speaking background: in Helsinki, they are projected to form 26% of the population; in Espoo, 30%; and in Vantaa, 34%. The Helsinki region is projected to have 437,000 people of foreign linguistic backgrounds, compared to 201,000 in 2019.[241]

Language

.svg.png.webp)

Finnish and Swedish are the official languages of Finland. Finnish predominates nationwide while Swedish is spoken in some coastal areas in the west and south (with towns such as Ekenäs,[242] Pargas,[243] Närpes,[243] Kristinestad,[244] Jakobstad[245] and Nykarleby.[246]) and in the autonomous region of Åland, which is the only monolingual Swedish-speaking region in Finland.[247] The native language of 87.3% of the population is Finnish,[248][249] which is part of the Finnic subgroup of the Uralic language. The language is one of only four official EU languages not of Indo-European origin, and has no relation through descent to the other national languages of the Nordics. Conversely, Finnish is closely related to Estonian and Karelian, and more distantly to Hungarian and the Sámi languages.

Swedish is the native language of 5.2% of the population (Swedish-speaking Finns).[250] Finnish is dominant in all the country's larger cities; though Helsinki, Turku, and Vaasa were once predominantly Swedish-speaking, they have undergone a language shift since the 19th century, getting a Finnish-speaking majority.

Swedish is a compulsory school subject and general knowledge of the language is good among many non-native speakers: in 2005, a total of 47% of Finnish citizens reported the ability to speak Swedish, either as a primary or a secondary language.[251] Likewise, a majority of Swedish-speaking non-Ålanders can speak Finnish. However, most Swedish-speaking youths reported seldom using Finnish: 71% reported always or mostly speaking Swedish in social settings outside of their households.[252] The Finnish side of the land border with Sweden is unilingually Finnish-speaking. The Swedish across the border is distinct from the Swedish spoken in Finland. There is a sizeable pronunciation difference between the varieties of Swedish spoken in the two countries, although their mutual intelligibility is nearly universal.[253]

Finnish Romani is spoken by some 5,000–6,000 people; Romani and Finnish Sign Language are also recognized in the constitution. There are two sign languages: Finnish Sign Language, spoken natively by 4,000–5,000 people,[254] and Finland-Swedish Sign Language, spoken natively by about 150 people. Tatar is spoken by a Finnish Tatar minority of about 800 people whose ancestors moved to Finland mainly during Russian rule from the 1870s to the 1920s.[255]

The Sámi languages have an official status in parts of Lapland, where the Sámi, numbering around 7,000,[256] are recognized as an indigenous people. About a quarter of them speak a Sami language as their mother tongue.[257] The Sami languages that are spoken in Finland are Northern Sami, Inari Sami, and Skolt Sami.[note 3]

The rights of minority groups (in particular Sami, Swedish speakers, and Romani people) are protected by the constitution.[258]

The Nordic languages and Karelian are also specially recognized in parts of Finland.

The largest immigrant languages are Russian (1.6%), Estonian (0.9%), Arabic (0.7%), English (0.5%) and Somali (0.4%).[259]

English is studied by most pupils as a compulsory subject from the first grade (at seven years of age), formerly from the third or fifth grade, in the comprehensive school (in some schools other languages can be chosen instead),[260][261] as a result of which Finns' English language skills have been significantly strengthened over several decades.[262][263] German, French, Spanish and Russian can be studied as second foreign languages from the fourth grade (at 10 years of age; some schools may offer other options).[264]

About 93% of Finns can speak a second language.[265] The figures in this section should be treated with caution, as they come from the official Finnish population register. People can only register in one language and so bilingual or multilingual language users' language competencies are not properly included. A citizen of Finland that speaks bilingually Finnish and Swedish will often be registered as a Finnish-only speaker in this system. Similarly "old domestic language" is a category applied to some languages and not others for political, not linguistic reasons, for example, Russian.[266]

Largest cities

Largest cities or towns in Finland | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

Helsinki  Espoo |

1 | Helsinki | Uusimaa | 656 920 | 11 | Kouvola | Kymenlaakso | 81 187 |  Tampere  Vantaa |

| 2 | Espoo | Uusimaa | 292 796 | 12 | Joensuu | North Karelia | 76 935 | ||

| 3 | Tampere | Pirkanmaa | 241 009 | 13 | Lappeenranta | South Karelia | 72 662 | ||

| 4 | Vantaa | Uusimaa | 237 231 | 14 | Hämeenlinna | Tavastia Proper | 67 848 | ||

| 5 | Oulu | Northern Ostrobothnia | 207 327 | 15 | Vaasa | Ostrobothnia | 67 461 | ||

| 6 | Turku | Finland Proper | 194 391 | 16 | Seinäjoki | Southern Ostrobothnia | 64 238 | ||

| 7 | Jyväskylä | Central Finland | 143 420 | 17 | Rovaniemi | Lapland | 63 612 | ||

| 8 | Kuopio | Northern Savonia | 120 210 | 18 | Mikkeli | Southern Savonia | 52 573 | ||

| 9 | Lahti | Päijänne Tavastia | 119 984 | 19 | Kotka | Kymenlaakso | 51 679 | ||

| 10 | Pori | Satakunta | 83 684 | 20 | Salo | Finland Proper | 51 564 | ||

Religion

Religions in Finland (2019)[267]