Lithuanian language

Lithuanian (Lithuanian: lietuvių kalba) is an Eastern Baltic language belonging to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family. It is the official language of Lithuania and one of the official languages of the European Union. There are about 2.8 million[2] native Lithuanian speakers in Lithuania and about 200,000 speakers elsewhere.

| Lithuanian | |

|---|---|

| lietuvių kalba | |

| Pronunciation | [lʲɪɛˈtʊvʲuː kɐɫˈbɐ ] |

| Native to | Lithuania |

| Region | Baltic |

| Ethnicity | Lithuanians |

Native speakers | 3.0 million (2012)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Proto-Indo-European

|

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Lithuanian alphabet) Lithuanian Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Commission of the Lithuanian Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | lt |

| ISO 639-2 | lit |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:lit – Modern Lithuanianolt – Old Lithuanian |

| Glottolog | lith1251 |

| Linguasphere | 54-AAA-a |

Map of the area of the Lithuanian language in the late 20th century and the 21st century | |

Lithuanian is closely related to the neighbouring Latvian language. It is written in a Latin script. It is said to be the most conservative of the existing Indo-European languages, retaining features of the Proto-Indo-European language that had disappeared through development from other descendant languages.[3][4][5]

History

Anyone wishing to hear how Indo-Europeans spoke should come and listen to a Lithuanian peasant.

— Antoine Meillet.[6]

Among Indo-European languages, Lithuanian is conservative in some aspects of its grammar and phonology, retaining archaic features otherwise found only in ancient languages such as Sanskrit[7] (particularly its early form, Vedic Sanskrit) or Ancient Greek. For this reason, it is an important source for the reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European language despite its late attestation (with the earliest texts dating only to c. 1500).[4]

Lithuanian was studied by linguists such as Franz Bopp, August Schleicher, Adalbert Bezzenberger, Louis Hjelmslev,[8] Ferdinand de Saussure,[9] Winfred P. Lehmann and Vladimir Toporov[10] and others.

The Proto-Balto-Slavic language branched off directly from Proto-Indo-European, then sub-branched into Proto-Baltic and Proto-Slavic. Proto-Baltic branched off into Proto-West Baltic and Proto-East Baltic.[7] Baltic languages passed through a Proto-Balto-Slavic stage, from which Baltic languages retain numerous exclusive and non-exclusive lexical, morphological, phonological and accentual isoglosses in common with the Slavic languages, which represent their closest living Indo-European relatives. Moreover, with Lithuanian being so archaic in phonology, Slavic words can often be deduced from Lithuanian by regular sound laws; for example, Lith. vilkas and Polish wilk ← PBSl. *wilkás (cf. PSl. *vьlkъ) ← PIE *wĺ̥kʷos, all meaning "wolf".

According to some glottochronological speculations,[11][12] the Eastern Baltic languages split from the Western Baltic ones between AD 400 and 600. The Greek geographer Ptolemy had already written of two Baltic tribe/nations by name, the Galindai and Sudinoi (Γαλίνδαι, Σουδινοί) in the 2nd century AD. The differentiation between Lithuanian and Latvian started after 800; for a long period, they could be considered dialects of a single language. At a minimum, transitional dialects existed until the 14th or 15th century and perhaps as late as the 17th century. Also, the 13th and 14th century occupation of the western part of the Daugava basin (closely coinciding with the territory of modern Latvia) by the German Sword Brethren had a significant influence on the language's independent development.

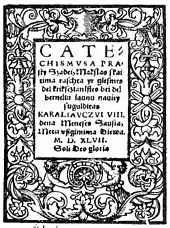

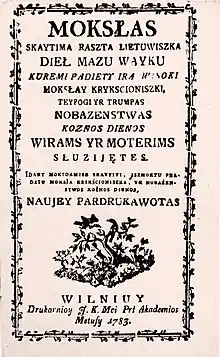

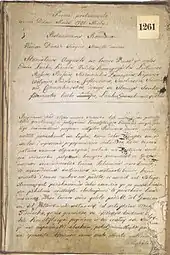

The earliest surviving written Lithuanian text is a translation dating from about 1503–1525 of the Lord's Prayer, the Hail Mary, and the Nicene Creed written in the Southern Aukštaitian dialect. Printed books existed after 1547, but the level of literacy among Lithuanians was low through the 18th century, and books were not commonly available. In 1864, following the January Uprising, Mikhail Muravyov, the Russian Governor General of Lithuania, banned the language in education and publishing and barred use of the Latin alphabet altogether, although books printed in Lithuanian continued to be printed across the border in East Prussia and in the United States. Brought into the country by book smugglers (Lithuanian: knygnešiai) despite the threat of stiff prison sentences, they helped fuel a growing nationalist sentiment that finally led to the lifting of the ban in 1904.

Jonas Jablonskis (1860–1930) made significant contributions to the formation of the standard Lithuanian language. The conventions of written Lithuanian had been evolving during the 19th century, but Jablonskis, in the introduction to his Lietuviškos kalbos gramatika, was the first to formulate and expound the essential principles that were so indispensable to its later development. His proposal for Standard Lithuanian was based on his native Western Aukštaitijan dialect with some features of the eastern Prussian Lithuanians' dialect spoken in Lithuania Minor. These dialects had preserved archaic phonetics mostly intact due to the influence of the neighbouring Old Prussian language, while the other dialects had experienced different phonetic shifts. Lithuanian has been the official language of Lithuania since 1918. During the Soviet era (see History of Lithuania), it was used in official discourse along with Russian, which, as the official language of the USSR, took precedence over Lithuanian.[13]

Classification

Lithuanian is one of two living Baltic languages, along with Latvian, and they constitute the eastern branch of Baltic languages family.[14] An earlier Baltic language, Old Prussian, was extinct by the 18th century; the other Western Baltic languages, Curonian and Sudovian, became extinct earlier. Some theories, such as that of Jānis Endzelīns, considered that the Baltic languages form their own distinct branch of the family of Indo-European languages. There is also an opinion that suggests the union of Baltic and Slavic languages into a distinct sub-family of Balto-Slavic languages amongst the Indo-European family of languages. Such an opinion was first represented by the likes of August Schleicher,[15] and to a certain extent, Antoine Meillet.[15] Endzelīns thought that the similarity between Baltic and Slavic was explicable through language contact while Schleicher, Meillet and others argued for a genetic kinship between the two families.

An attempt to reconcile the opposing stances was made by Jan Michał Rozwadowski. He proposed that the two language groups were indeed a unity after the division of Indo-European, but also suggested that after the two had divided into separate entities (Baltic and Slavic), they had posterior contact. The genetic kinship view is augmented by the fact that Proto-Balto-Slavic is easily reconstructible with important proofs in historic prosody. The alleged (or certain, as certain as historic linguistics can be) similarities due to contact are seen in such phenomena as the existence of definite adjectives formed by the addition of an inflected pronoun (descended from the same Proto-Indo-European pronoun), which exist in both Baltic and Slavic yet nowhere else in the Indo-European family (languages such as Albanian and the Germanic languages developed definite adjectives independently), and that are not reconstructible for Proto-Balto-Slavic, meaning that they most probably developed through language contact.

The Baltic hydronyms area stretches from the Vistula River in the west to the east of Moscow and from the Baltic Sea in the north to the south of Kyiv.[16][17] Vladimir Toporov and Oleg Trubachyov (1961, 1962) studied Baltic hydronyms in the Russian and Ukrainian territory.[18] Hydronyms and archeology analysis show that the Slavs started migrating to the Baltic areas east and north-east directions in the 6–7th centuries, before then, the Baltic and Slavic boundary was south of the Pripyat River.[19] In the 1960s Vladimir Toporov and Vyacheslav Ivanov made the following conclusions about the relationship between the Baltic and Slavic languages: a) the Proto-Slavic language formed from the peripheral-type Baltic dialects; b) the Slavic linguistic type formed later from the structural model of the Baltic languages; c) the Slavic structural model is a result of a transformation of the structural model of the Baltic languages. These scholars’ theses do not contradict the Baltic and Slavic languages closeness and from a historical perspective specify the Baltic-Slavic languages evolution.[20][21]

Geographic distribution

Lithuanian is spoken mainly in Lithuania. It is also spoken by ethnic Lithuanians living in today's Belarus, Latvia, Poland, and the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia, as well as by sizable emigrant communities in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uruguay, and Spain.

2,955,200 people in Lithuania (including 3,460 Tatars), or about 86% of the 2015 population, are native Lithuanian speakers; most Lithuanian inhabitants of other nationalities also speak Lithuanian to some extent. The total worldwide Lithuanian-speaking population is about 3,200,000.

Official status

Lithuanian is the state language of Lithuania and an official language of the European Union.

Dialects

The Lithuanian language has two dialects: Aukštaitian (Highland Lithuanian), and Samogitian (Lowland Lithuanian). There are significant differences between standard Lithuanian and Samogitian and these are often described as separate languages. The modern Samogitian dialect formed in the 13th–16th centuries under the influence of the Curonian language. Lithuanian dialects are closely connected with ethnographical regions of Lithuania.

Dialects are divided into subdialects. Both dialects have three subdialects. Samogitian is divided into West, North and South; Aukštaitian into West (Suvalkiečiai), South (Dzūkai) and East.

Standard Lithuanian is derived mostly from Western Aukštaitian dialects, including the Eastern dialect of Lithuania Minor. The influence of other dialects is more significant in the vocabulary of standard Lithuanian.

Script

%252C_mentioned_in_Chronik_des_Konstanzer_Konzils_by_Ulrich_von_Richental%252C_15th_century.jpg.webp)

Lithuanian uses the Latin script supplemented with diacritics. It has 32 letters. In the collation order, y follows immediately after į (called i nosinė), because both y and į represent the same long vowel [iː]:

| Majuscule forms (also called uppercase or capital letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Ą | B | C | Č | D | E | Ę | Ė | F | G | H | I | Į | Y | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | Š | T | U | Ų | Ū | V | Z | Ž |

| Minuscule forms (also called lowercase or small letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | ą | b | c | č | d | e | ę | ė | f | g | h | i | į | y | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | š | t | u | ų | ū | v | z | ž |

In addition, the following digraphs are used, but are treated as sequences of two letters for collation purposes. The digraph ch represents a single sound, the velar fricative [x], while dz and dž are pronounced like straightforward combinations of their component letters (sounds):

Dz dz [dz] (dzė), Dž dž [dʒ] (džė), Ch ch [x] (cha).

The Lithuanian writing system is largely phonemic, i.e., one letter usually corresponds to a single phoneme (sound). There are a few exceptions: for example, the letter i represents either the vowel [ɪ], as in the English sit, or is silent and merely indicates that the preceding consonant is palatalized. The latter is largely the case when i occurs after a consonant and is followed by a back or a central vowel, except in some borrowed words (e.g., the first consonant in lūpa [ˈɫûːpɐ], "lip", is a velarized dental lateral approximant; on the other hand, the first consonant in liūtas [ˈlʲuːt̪ɐs̪], "lion", is a palatalized alveolar lateral approximant; both consonants are followed by the same vowel, the long [uː], and no [ɪ] can be pronounced in liūtas). Before the 20th century, due to the Polish influence, the Lithuanian alphabet included the Polish Ł for the first sound and regular L (without a following i) for the second: łupa, lutas.

A macron (on u), an ogonek (on a, e, i, and u), and y (in place of i) are used for grammatical and historical reasons and always denote vowel length in Modern Standard Lithuanian. Acute, grave, and tilde diacritics are used to indicate pitch accents. However, these pitch accents are generally not written, except in dictionaries, grammars, and where needed for clarity, such as to differentiate homonyms and dialectal use.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hard | soft | hard | soft | hard | soft | hard | soft | |||

| Nasal | m | mʲ | n | nʲ | ||||||

| Stop | voiceless | p | pʲ | t | tʲ | k | kʲ | |||

| voiced | b | bʲ | d | dʲ | g | ɡʲ | ||||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s | t͡sʲ | t͡ʃ | t͡ɕ | |||||

| voiced | d͡z | d͡zʲ | d͡ʒ | d͡ʑ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | (f) | (fʲ) | s | sʲ | ʃ | ɕ | (x) | (xʲ) | |

| voiced | v | vʲ | z | zʲ | ʒ | ʑ | j | (ɣ) | (ɣʲ) | |

| Approximant | ɫ | lʲ | ||||||||

| Trill | r | rʲ | ||||||||

All Lithuanian consonants except /j/ have two variants: the non-palatalized one represented by the IPA symbols in the chart, and the palatalized one (i.e. /b/ – /bʲ/, /d/ – /dʲ/, /ɡ/ – /ɡʲ/, and so on). The consonants /f/, /x/, /ɣ/ and their palatalized variants are only found in loanwords.

/t͡ɕ, d͡ʑ, ɕ, ʑ/ have been traditionally transcribed with ⟨t͡ʃʲ, d͡ʒʲ, ʃʲ, ʒʲ⟩, but they can be seen as equivalent transcriptions, with the former set being somewhat easier to write.[23]

Vowels

Lithuanian has six long vowels and four short ones (not including disputed phonemes marked in brackets). Length has traditionally been considered the distinctive feature, though short vowels are also more centralized and long vowels more peripheral:

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | iː | ɪ | ʊ | uː | ||

| Mid | eː | ɛ, (e) | (ɔ) | oː | ||

| Open | æː | ɐ | aː | |||

- /e, ɔ/ are restricted to loanwords. Many speakers merge the former with /ɛ/.[24]

Diphthongs

Lithuanian is traditionally described as having nine diphthongs, ai, au, ei, eu, oi, ou, ui, ie, and uo. However, some approaches (i.e., Schmalstieg 1982) treat them as vowel sequences rather than diphthongs; indeed, the longer component depends on the type of stress, whereas in diphthongs, the longer segment is fixed.

| stressless or tilde |

acute stress | |

|---|---|---|

| ai | [ɐɪ̯ˑ] | [âˑɪ̯] |

| ei | [ɛɪ̯ˑ] | [æ̂ˑɪ̯] |

| au | [ɒʊ̯ˑ] | [âˑʊ̯] |

| eu | [ɛʊ̯ˑ] | [ɛ̂ʊ̯] |

| iau | [ɛʊ̯ˑ] | [ɛ̂ˑʊ̯] |

| ie | [iə] | [îə][25] |

| oi | — | [ɔ̂ɪ̯] |

| ou | — | [ɔ̂ʊ̯] |

| ui | [ʊɪ̯ˑ] | [ʊ̂ɪ̯] |

| uo | [uə] | [ûə][25] |

Pitch accent

The Lithuanian prosodic system is characterized by free accent and distinctive quantity. Its accentuation is sometimes described as a simple tone system, often called pitch accent.[26] In lexical words, one syllable will be tonically prominent. A heavy syllable—that is, a syllable containing a long vowel, diphthong, or a sonorant coda—may have one of two tones, falling tone (or acute tone) or rising tone (or circumflex tone). Light syllables (syllables with short vowels and optionally also obstruent codas) do not have the two-way contrast of heavy syllables.

Grammar

Lithuanian is a highly inflected language. In Lithuanian, there are two grammatical genders for nouns (masculine and feminine) and three genders for adjectives, pronouns, numerals and participles (masculine, feminine and neuter). Every attribute must agree with the gender and number of the noun. The neuter forms of other parts of speech are used with a subject of an undefined gender (a pronoun, an infinitive etc.).

There are twelve noun and five adjective declensions and one (masculine and feminine) participle declension.[27]

Nouns and other parts of nominal morphology are declined in seven cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, instrumental, locative, and vocative. In older Lithuanian texts, three additional varieties of the locative case are found: illative, adessive and allative. The most common are the illative, which still is used, mostly in spoken language, and the allative, which survives in the standard language in some idiomatic usages. The adessive is nearly extinct. These additional cases are probably due to the influence of Uralic languages, with which Baltic languages have had a longstanding contact. (Uralic languages possess a great variety of noun cases, a number of which are specialised locative cases.)

Lithuanian verbal morphology shows a number of innovations; namely, the loss of synthetic passive (which is hypothesized based on the more archaic though long-extinct Indo-European languages), synthetic perfect (formed by means of reduplication) and aorist; forming subjunctive and imperative with the use of suffixes plus flexions as opposed to solely flections in, e.g., Ancient Greek; loss of the optative mood; merging and disappearing of the -t- and -nt- markers for the third-person singular and plural, respectively (this, however, occurs in Latvian and Old Prussian as well and may indicate a collective feature of all Baltic languages).

On the other hand, the Lithuanian verbal morphology retains a number of archaic features absent from most modern Indo-European languages (but shared with Latvian). This includes the synthetic form of the future tense with the help of the -s- suffix and three principal verbal forms with the present tense stem employing the -n- and -st- infixes.

There are three verbal conjugations. The verb būti is the only auxiliary verb in the language. Together with participles, it is used to form dozens of compound forms.

In the active voice, each verb can be inflected for any of the following moods:

- Indicative

- Indirect

- Imperative

- Conditional/subjunctive

In the indicative mood and indirect moods, all verbs can have eleven tenses:

- simple: present (nešu), past (nešiau), past iterative (nešdavau) and future (nešiu)

- compound:

- present perfect (esu nešęs), past perfect (buvau nešęs), past iterative perfect (būdavau nešęs), future perfect (būsiu nešęs)

- past inchoative (buvau benešąs), past iterative inchoative (būdavau benešąs), future inchoative (būsiu benešąs)

The indirect mood, used only in written narrative speech, has the same tenses corresponding to the appropriate active participle in nominative case; e.g., the past of the indirect mood would be nešęs, while the past iterative inchoative of the indirect mood would be būdavęs benešąs. Since it is a nominal form, this mood cannot be conjugated but must match the subject's number and gender.

The subjunctive (or conditional) and the imperative moods have three tenses. Subjunctive: present (neščiau), past (būčiau nešęs), inchoative (būčiau benešąs); imperative: present (nešk), perfect (būk nešęs) and inchoative (būk benešąs).

The infinitive has only one form (nešti). These forms, except the infinitive and indirect mood, are conjugative, having two singular, two plural persons, and the third person form common both for plural and singular.

In the passive voice, the form number is not as rich as in the active voice. There are two types of passive voice in Lithuanian: present participle (type I) and past participle (type II) (in the examples below types I and II are separated with a slash). They both have the same moods and tenses:

- Indicative mood: present (esu nešamas/neštas), past (buvau nešamas/neštas), past iterative (būdavau nešamas/neštas) and future (būsiu nešamas/neštas)

- Indirect mood: present (esąs nešamas/neštas), past (buvęs nešamas/neštas), past iterative (būdavęs nešamas/neštas) and future (būsiąs nešamas/neštas).

- Imperative mood: present (type I only: būk nešamas), past (type II only: būk neštas).

- Subjunctive / conditional mood: present (type I only: būčiau nešamas), past (type II only: būčiau neštas).

Lithuanian has the richest participle system of all Indo-European languages, having participles derived from all simple tenses with distinct active and passive forms, and two gerund forms.

In practical terms, the rich overall inflectional system makes the word order have a different meaning than in more analytic languages such as English. The English phrase "a car is coming" translates as "atvažiuoja automobilis" (the theme first), while "the car is coming" – "automobilis atvažiuoja" (the theme first; word order inversion).

Lithuanian also has a very rich word derivation system and an array of diminutive suffixes.

The first prescriptive grammar book of Lithuanian was commissioned by the Duke of Prussia, Frederick William, for use in the Lithuanian-speaking parishes of East Prussia. It was written in Latin and German by Daniel Klein and published in Königsberg in 1653 or 1654. The first scientific Compendium of Lithuanian language was published in German in 1856/57 by August Schleicher, a professor at Prague University. In it he describes Prussian-Lithuanian, which later became the "skeleton" (Būga) of modern Lithuanian.

Today there are two definitive books on Lithuanian grammar: one in English, the Introduction to Modern Lithuanian (called Beginner's Lithuanian in its newer editions) by Leonardas Dambriūnas, Antanas Klimas and William R. Schmalstieg; and another in Russian, Vytautas Ambrazas' Грамматика литовского языка (The Grammar of the Lithuanian Language). Another recent book on Lithuanian grammar is the second edition of Review of Modern Lithuanian Grammar by Edmund Remys, published by Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, Chicago, 2003.

Vocabulary

Indo-European vocabulary

Lithuanian retains cognates to many words found in classical languages, such as Sanskrit and Latin. These words are descended from Proto-Indo-European. A few examples are the following:

- Lith. sūnus and Skt. sūnu (son)

- Lith. avis and Skt. avi and Lat. ovis (sheep)

- Lith. dūmas and Skt. dhūma and Lat. fumus (fumes, smoke)

- Lith. antras and Skt. antara (second, the other)

- Lith. vilkas and Skt. vṛka (wolf)

- Lith. ratas and Lat. rota (wheel) and Skt. ratha (carriage)

- Lith. senis and Lat. senex (an old man) and Skt. sanas (old)

- Lith. vyras and Lat. vir (a man) and Skt. vīra (man)

- Lith. angis and Lat. anguis (a snake in Latin, a species of snakes in Lithuanian)

- Lith. linas and Lat. linum (flax, compare with English 'linen')

- Lith. ariu and Lat. aro (I plow)

- Lith. jungiu and Lat. iungo, and Skt. yuñje (mid.), (I join)

- Lith. gentys and Lat. gentes and Skt. játi (tribes)

- Lith. mėnesis and Lat. mensis and Skt. masa (month)

- Lith. dantis and Lat. dens and Skt. danta (tooth)

- Lith. naktis and Lat. noctes (plural of nox) and Skt. naktam (night)

- Lith. ugnis and Lat. ignis and Skt. agni (fire)

- Lith. sėdime and Lat. sedemus and Skt. sīdama (we sit)

This even extends to grammar, where for example Latin noun declensions ending in -um often correspond to Lithuanian -ų, with the Latin and Lithuanian fourth declensions being particularly close. Many of the words from this list are similar to other Indo-European languages, including English and Russian. The contribution of Lithuanian was influential in the reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European language.

Lexical and grammatical similarities between Baltic and Slavic languages suggest an affinity between these two language groups. On the other hand, there exist a number of Baltic (particularly Lithuanian) words without counterparts in Slavic languages, but which are similar to words in Sanskrit or Latin. The history of the relationship between Baltic and Slavic languages, and our understanding of the affinity between the two groups, remain in dispute (see: Balto-Slavic languages).

Loanwords

In a 1934 book entitled Die Germanismen des Litauischen. Teil I: Die deutschen Lehnwörter im Litauischen, K. Alminauskis found 2,770 loanwords, of which about 130 were of uncertain origin. The majority of the loanwords were found to have been derived from the Polish, Belarusian, and German languages, with some evidence that these languages all acquired the words from contacts and trade with Prussia during the era of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[28] Loanwords comprised about 20% of the vocabulary used in the first book printed in the Lithuanian language in 1547, Martynas Mažvydas's Catechism.[29] But as a result of language preservation and purging policies, Slavic loanwords currently constitute only 1.5% of the Standard Lithuanian lexicon, while German loanwords constitute only 0.5% of it.[30] The majority of loanwords in the 20th century arrived from the Russian language.[31]

Towards the end of the 20th century, a number of words and expressions related to new technologies and telecommunications were borrowed from the English language. The Lithuanian government has an established language policy that encourages the development of equivalent vocabulary to replace loanwords.[32] However, despite the government's best efforts to avoid the use of loanwords in the Lithuanian language, many English words have become accepted and are now included in Lithuanian language dictionaries.[33][34] In particular, words having to do with new technologies have permeated the Lithuanian vernacular, including such words as:

- Monitorius (vaizduoklis) (computer monitor)

- Faksas (fax)

- Kompiuteris (computer)

- Failas (byla, rinkmena) (electronic file)

Other common foreign words have also been adopted by the Lithuanian language. Some of these include:

- Taksi (taxi)

- Pica (pizza)

- Alkoholis (alcohol)

- Bankas (bank)

- Pasas (passport, pass)

- Parkas (park, park)

These words have been modified to suit the grammatical and phonetic requirements of the Lithuanian language, mostly by adding -as suffix, but their foreign roots are obvious.

Old Lithuanian

The language of the earliest Lithuanian writings, in the 16th and 17th centuries, is known as Old Lithuanian and differs in some significant respects from the Lithuanian of today.

Universitas lingvarum Litvaniae, published in Vilnius, 1737, is the oldest surviving grammar of the Lithuanian language published in the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[35]

Besides the specific differences given below, nouns, verbs, and adjectives still had separate endings for the dual number. The dual persists today in some dialects. Example:

| Case | "two good friends" |

|---|---|

| Nom-Acc | dù gerù draugù |

| Dat | dvı̇́em gerı̇́em draugám |

| Inst | dviem̃ geriem̃ draugam̃ |

Pronunciation

The vowels written ą, ę, į, ų were still pronounced as long nasal vowels,[36] not as long oral vowels as in today's Lithuanian.

The original Baltic long ā was still retained as such, e.g. bralis "brother" (modern brólis).

Nouns

Compared to the modern language, there were three additional cases, formed under the influence of the Finnic languages. The original locative case had been replaced by four so-called postpositive cases, the inessive case, illative case, adessive case and allative case, which correspond to the prepositions "in", "into", "at" and "towards", respectively. They were formed by affixing a postposition to one of the previous cases:

- The inessive added -en to the original locative.

- The illative added -n(a) to the accusative.

- The adessive added -pie to the original locative.

- The allative added -pie to the genitive.

The inessive has become the modern locative case, while the other three have disappeared. Note, however, that the illative case is still used occasionally in the colloquial language (mostly in the singular): Lietuvon "to Lithuania", miestan "to the city". This form is relatively productive: for instance, it is not uncommon to hear "skrendame Niujorkan (we are flying to New York)".

The uncontracted dative plural -mus was still common.

Adjectives

Adjectives could belong to all four accent classes in Old Lithuanian (now they can only belong to classes 3 and 4).

Additional remnants of i-stem adjectives still existed, e.g.:

- loc. sg. didimè pulkè "in the big crowd" (now didžiame)

- loc. sg. gerèsnime "better" (now geresniamè)

- loc. sg. mažiáusime "smallest" (now mažiáusiame)

Additional remnants of u-stem adjectives still existed, e.g. rūgštùs "sour":

| Case | Newer | Older |

|---|---|---|

| Inst sg | rūgščiù | rūgštumı̇̀ |

| Loc sg | rūgščiamè | rūgštumè |

| Gen pl | rūgščių̃ | rūgštų̃ |

| Acc pl | rū́gščius | rū́gštus |

| Inst pl | rūgščiaı̇̃s | rūgštumı̇̀s |

No u-stem remnants existed in the dative singular and locative plural.

Definite adjectives, originally involving a pronoun suffixed to an adjective, had not merged into a single word in Old Lithuanian. Examples:

- pa-jo-prasto "ordinary" (now pàprastojo)

- nu-jie-vargę "tired" (now nuvar̃gusieji)

Verbs

The Proto-Indo-European class of athematic verbs still existed in Old Lithuanian:

| 'be' | 'remain' | 'give' | 'save' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sg | esmı̇̀ | liekmı̇̀ | dúomi | gélbmi |

| 2nd sg | esı̇̀ | lieksı̇̀ | dúosi | gélbsi |

| 3rd sg | ẽst(i) | liẽkt(i) | dúost(i) | gélbt(i) |

| 1st dual | esvà | liekvà | dúova | gélbva |

| 2nd dual | està | liektà | dúosta | gélbta |

| 1st pl | esmè | liekmè | dúome | gélbme |

| 2nd pl | estè | liektè | dúoste | gélbte |

| 3rd pl | ẽsti | liẽkt(i) | dúost(i) | gélbt(i) |

The optative mood (i.e. the third-person imperative) still had its own endings, -ai for third-conjugation verbs and -ie for other verbs, instead of using regular third-person present endings.

Syntax

Word order was freer in Old Lithuanian. For example, a noun in the genitive case could either precede or follow the noun it modifies.

See also

- Lithuanian dictionaries

- Lithuanian literature

- Martynas Mažvydas

Citations

- Lithuanian language at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- Rodiklių duomenų bazė. "Oficialiosios statistikos portalas". osp.stat.gov.lt (in Lithuanian).

- Zinkevičius, Z. (1993). Rytų Lietuva praeityje ir dabar [Eastern Lithuania in the Past and Now] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidykla. p. 9. ISBN 5-420-01085-2.

...linguist generally accepted that Lithuanian language is the most archaic among live Indo-European languages...

- "Lithuanian Language". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Bonifacas, Stundžia (20 November 2021). "How did Vytautas the Great speak and would we manage to have a conversation with VI century Lithuanians?". 15min. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Ever wanted to travel back in time? Talk to a Lithuanian! -". Terminology Coordination Unit of the European Parliament. 19 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- Smalstieg, William (1982). "The Origin of the Lithuanian Language". Lituanus. 28 (1). Retrieved 7 August 2016 – via lituanus.org.

- Chapman, Siobhan; Routledge, Christopher, eds. (2005). Key Thinkers in Linguistics and the Philosophy of Language. Oxford University Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780195187687.

- Joseph, John E. (2009). "Why Lithuanian Accentuation Mattered to Saussure" (PDF). Language & History. 52 (2): 182–198. doi:10.1179/175975309X452067. S2CID 144780177. Retrieved 1 April 2018 – via lel.ed.ac.uk.

- Sabaliauskas, Algirdas (2007). "Remembering Vladimir Toporov". Lituanus. 53 (2). Retrieved 4 April 2018 – via lituanus.org.

- Girdenis, Aleksas; Mažiulis, Vytautas (1994). "Baltų kalbų divergencinė chronologija". Baltistica (in Lithuanian). 27 (2): 10. doi:10.15388/baltistica.27.2.204.

- Novotná, Petra; Blažek, Václav (2007). "Glottochronology and Its Application on the Balto-Slavic Languages". Baltistica. 42 (3): 208–209. doi:10.15388/baltistica.42.3.1178.

- Dini (2000), p. 362 "Priešingai nei skelbė leninietiškos deklaracijos apie tautas ("Jokių privilegijų jokiai tautai ir jokiai kalbai"), reali TSRS politika – kartu ir kalbų politika – buvo ne kas kita kaip rusinimas77. Ir 1940–1941 metais, iš karto po priverstinio Pabaltijo valstybių įjungimo į TSRS, ir vėliau vyraujanti kalbos politikos linija Lietuvos TSRS ir Latvijos TSRS buvo tautinių kalbų raidos derinimas su socialistinių nacijų raida78. Tokia padėtis tęsėsi penkiasdešimt metų79."

- Dahl, Östen; Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Maria (2001). Dahl, Östen; Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Maria (eds.). Circum-Baltic Languages. Studies in Language Companion Series 55. Vol. II: Grammar and Typology. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 43. doi:10.1075/slcs.55.02dah. ISBN 9789027230591.

- Dini, Pietro U.; Richardson, Milda B.; Richardson, Robert E. (2014). Foundations of Baltic languages (PDF). Vilnius: Eugrimas. p. 206. ISBN 978-609-437-263-6. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q., eds. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. pp. 49. ISBN 9781884964985.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Padstow: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 378–379.

- Dini (2000), p. 38

- Smoczyński, W. (1986). Języki indoeuropejskie. Języki bałtyckie [Indo-European Languages. Baltic Languages] (in Lithuanian). Warszawa: PWN.

- Dini (2000), p. 143

- Birnbaum, Kh Х Бирнбаум (1985). "O dvukh osnovnykh napravleniyakh v yazykovom razvitii" О двух основных направлениях в языковом развитии (PDF). Voprosy yazykoznaniya Вопросы языкознания (in Russian). 1985 (2): 36.

- Girdenis, Aleksas; Zinkevičius, Zigmas (1966). "Dėl lietuvių kalbos tarmių klasifikacijos" [Regarding the Classification of Lithuanian Dialects]. Kalbotyra (in Lithuanian). 14: 139–147. doi:10.15388/Knygotyra.1966.18940.

- Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996:?)

- Ambrazas et al. (1997), p. 24.

- Girdenis, Aleksas (2009). "Vadinamųjų sutaptinių dvibalsių [ie uo] garsinė ir fonologinė sudėtis". Baltistica (in Lithuanian). 44 (2): 213–242. doi:10.15388/baltistica.44.2.1313.

- Dogil, Grzegorz; Möhler, Gregor (1998). Phonetic Invariance and Phonological Stability: Lithuanian Pitch Accents. 5th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing, Sydney, Australia, November 30 – December 4, 1998.

- Dabartinės lietuvių kalbos gramatika [A Grammar of Modern Lithuanian] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius. 1997.

- Cepiene, N. (2006). "Ways of Germanisms into Lithuanian". Acta Baltico-Slavica (Abstract). 30: 241–250. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012.

- Zinkevičius, Zigmas (1996). "Martynas Mažvydas' Language". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2007 – via pirmojiknyga.mch.mii.lt.

- "Skoliniai". Studijos (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- Sakalauskienė, V. (2006). "Slavic loanwords in the northern sub-dialect of the southern part of west high Lithuanian". Acta Baltico-Slavica (Abstract). 30: 221–231. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- Seimas of Lithuania (2003). "State Language Policy Guidelines 2003–2008". Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- "English to Lithuanian to English Dictionary". Dicts.info. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011.

- "Lingvozone English to Lithuanian Online Dictionary". Lingvozone.com. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008.

- Sabaliauskas, Algirdas. "Universitas lingvarum Litvaniae". Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- Ambrazas et al. (1997), p. 13.

General sources

- Ambrazas, Vytautas; Geniušienė, Emma; Girdenis, Aleksas; Sližienė, Nijolė; Valeckienė, Adelė; Valiulytė, Elena; Tekorienė, Dalija; Pažūsis, Lionginas (1997), Ambrazas, Vytautas (ed.), Lithuanian Grammar, Vilnius: Institute of the Lithuanian Language, ISBN 9986-813-22-0

- Dambriūnas, Leonardas; Antanas Klimas, William R. Schmalstieg, Beginner's Lithuanian, Hippocrene Books, 1999, ISBN 0-7818-0678-X. Older editions (copyright 1966) called "Introduction to modern Lithuanian".

- Dini, P. U. (2000). Baltų kalbos: Lyginamoji istorija [Baltic Languages: A Comparative History] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. ISBN 5-420-01444-0.

- Klimas, Antanas. "Baltic and Slavic revisited". Lituanus vol. 19, no. 1, Spring 1973. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4.

- Remys, Edmund, Review of Modern Lithuanian Grammar, Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, Chicago, 2nd revised edition, 2003.

- Remys, Edmund, General distinguishing features of various Indo-European languages and their relationship to Lithuanian, Indogermanische Forschungen, Berlin, New York, 2007.

- Zinkevičius, Zigmas, "Lietuvių kalbos istorija" ("History of Lithuanian Language") Vol.1, Vilnius: Mokslas, 1984, ISBN 5-420-00102-0.

External links

- Baltic Online (part of Early Indo-European Online) – Lithuanian and Old Lithuanian grammar

- Academic Dictionary of Lithuanian

- The Historical Grammar of Lithuanian language

- 2005 analysis of Indo-European linguistic relationships

- Lithuanian verbs training

- Lithuanian verbs test

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – Lithuanian language

- glottothèque – Ancient Indo-European Grammars online, an online collection of introductory videos to Ancient Indo-European languages produced by the University of Göttingen

%252C_word_(%C5%A1yk%C5%A1tumas).jpg.webp)

%252C_words_(tepridau%C5%BEia%252C_ubagyst%C4%97).jpg.webp)