Iron Age

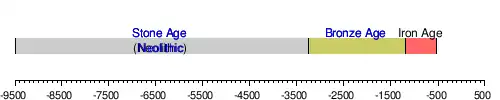

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly applied to Iron Age Europe and the Ancient Near East, but also, by analogy, to other parts of the Old World.

| Part of a series on the |

| Iron Age |

|---|

| ↑ Bronze Age |

| ↓ Ancient history |

| Part of a series on |

| Human history and prehistory |

|---|

| ↑ before Homo (Pliocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future (Holocene epoch) |

| History of technology |

|---|

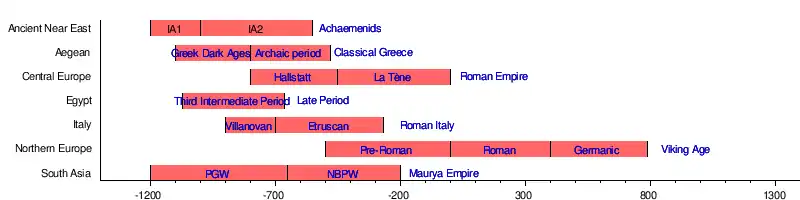

The duration of the Iron Age varies depending on the region under consideration. It is defined by archaeological convention. The "Iron Age" begins locally when the production of iron or steel has advanced to the point where iron tools and weapons replace their bronze equivalents in common use.[1] In the Ancient Near East, this transition took place in the wake of the so-called Bronze Age collapse, in the 12th century BCE. The technology soon spread throughout the Mediterranean Basin region and to South Asia (Iron Age in India) between the 12th and 11th century BCE. Its further spread to Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and Central Europe is somewhat delayed, and Northern Europe was not reached until around the start of the 5th century BCE.

The Iron Age is taken to end, also by convention, with the beginning of the historiographical record. This usually does not represent a clear break in the archaeological record; for the Ancient Near East, the establishment of the Achaemenid Empire c. 550 BCE is traditionally and still usually taken as a cut-off date, later dates being considered historical by virtue of the record by Herodotus, despite considerable written records from far earlier (well back into the Bronze Age) now being known. In Central and Western Europe, the Roman conquests of the 1st century BC serve as marking for the end of the Iron Age. The Germanic Iron Age of Scandinavia is taken to end c. AD 800, with the beginning of the Viking Age.

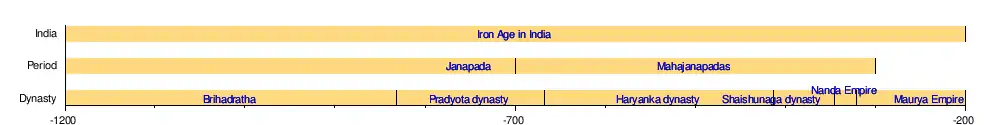

In the Indian sub-continent, the Iron Age is taken to begin with the ironworking Painted Gray Ware culture. Recent estimates suggest that it ranges from the 15th century BCE, through to the reign of Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE. The use of the term "Iron Age" in the archaeology of South, East, and Southeast Asia is more recent and less common than for Western Eurasia. In China, written history started before iron-working arrived, so the term is infrequently used. The Sahel (Sudan region) and Sub-Saharan Africa are outside of the three-age system, there being no Bronze Age, but the term "Iron Age" is sometimes used in reference to early cultures practicing ironworking, such as the Nok culture of Nigeria.

History of the concept

The three-age system was introduced in the first half of the 19th century for the archaeology of Europe in particular, and by the later 19th century expanded to the archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Its name harks back to the mythological "Ages of Man" of Hesiod. As an archaeological era, it was first introduced for Scandinavia by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen in the 1830s. By the 1860s, it was embraced as a useful division of the "earliest history of mankind" in general[2] and began to be applied in Assyriology. The development of the now-conventional periodization in the archaeology of the Ancient Near East was developed in the 1920s to 1930s.[3] As its name suggests, Iron Age technology is characterized by the production of tools and weaponry by ferrous metallurgy (ironworking), more specifically from carbon steel.

Chronology

|

Increasingly the Iron Age in Europe is being seen as a part of the Bronze Age collapse in the ancient Near East, in ancient India (with the post-Rigvedic Vedic civilization), ancient Iran, and ancient Greece (with the Greek Dark Ages). In other regions of Europe the Iron Age began in the 8th century BC in Central Europe and the 6th century BC in Northern Europe. The Near Eastern Iron Age is divided into two subsections, Iron I and Iron II. Iron I (1200–1000 BC) illustrates both continuity and discontinuity with the previous Late Bronze Age. There is no definitive cultural break between the 13th and 12th centuries BC throughout the entire region, although certain new features in the hill country, Transjordan and coastal region may suggest the appearance of the Aramaean and Sea People groups. There is evidence, however, of strong continuity with Bronze Age culture, although as one moves later into Iron Age the culture begins to diverge more significantly from that of the late 2nd millennium.

The Iron Age as an archaeological period is roughly defined as that part of the prehistory of a culture or region during which ferrous metallurgy was the dominant technology of metalworking.

The characteristic of an Iron Age culture is the mass production of tools and weapons made from steel, typically alloys with a carbon content between approximately 0.30% and 1.2% by weight. Only with the capability of the production of carbon steel does ferrous metallurgy result in tools or weapons that are equal or superior to bronze. The use of steel has been based as much on economics as on metallurgical advancements. Early steel was made by smelting iron.

By convention, the Iron Age in the Ancient Near East is taken to last from c. 1200 BC (the Bronze Age collapse) to c. 550 BC (or 539 BC), roughly the beginning of historiography with Herodotus; the end of the proto-historical period. In Central and Western Europe, the Iron Age is taken to last from c. 800 BC to c. 1 BC, in Northern Europe from c. 500 BC to AD 800.

In China, there is no recognizable prehistoric period characterized by ironworking, as Bronze Age China transitions almost directly into the Qin dynasty of imperial China; "Iron Age" in the context of China is sometimes used for the transitional period of c. 900 BC to 100 BC during which ferrous metallurgy was present even if not dominant.

Early ferrous metallurgy

The earliest-known iron artifacts are nine small beads dated to 3200 BC, which were found in burials at Gerzeh, Lower Egypt. They have been identified as meteoric iron shaped by careful hammering.[4] Meteoric iron, a characteristic iron–nickel alloy, was used by various ancient peoples thousands of years before the Iron Age. Such iron, being in its native metallic state, required no smelting of ores.[5][6]

Smelted iron appears sporadically in the archeological record from the middle Bronze Age. Whilst terrestrial iron is naturally abundant, temperatures above 1,250 °C (2,280 °F) are required to smelt it, placing it out of reach of commonly available technology until the end of the second millennium BC. In contrast, the components of bronze -- tin with a melting point of 231.9 °C (449.4 °F) and copper with a relatively moderate melting point of 1,085 °C (1,985 °F) -- were within the capabilities of Neolithic kilns, which date back to 6000 BC and were able to produce temperatures greater than 900 °C (1,650 °F).[7] In addition to specially designed furnaces, ancient iron production required the development of complex procedures for the removal of impurities, the regulation of the admixture of carbon, and the invention of hot-working to achieve a useful balance of hardness and strength in steel.

The earliest tentative evidence for iron-making is a small number of iron fragments with the appropriate amounts of carbon admixture found in the Proto-Hittite layers at Kaman-Kalehöyük in modern-day Turkey, dated to 2200–2000 BC. Akanuma (2008) concludes that "The combination of carbon dating, archaeological context, and archaeometallurgical examination indicates that it is likely that the use of ironware made of steel had already begun in the third millennium BC in Central Anatolia".[8] Souckova-Siegolová (2001) shows that iron implements were made in Central Anatolia in very limited quantities around 1800 BC and were in general use by elites, though not by commoners, during the New Hittite Empire (∼1400–1200 BC).[9]

Similarly, recent archaeological remains of iron-working in the Ganges Valley in India have been tentatively dated to 1800 BC. Tewari (2003) concludes that "knowledge of iron smelting and manufacturing of iron artifacts was well known in the Eastern Vindhyas and iron had been in use in the Central Ganga Plain, at least from the early second millennium BC".[10] By the Middle Bronze Age increasing numbers of smelted iron objects (distinguishable from meteoric iron by the lack of nickel in the product) appeared in the Middle East, Southeast Asia and South Asia. African sites are turning up dates as early as 2000-1200 BC.[11][12][13][14]

Modern archaeological evidence identifies the start of large-scale iron production in around 1200 BC, marking the end of the Bronze Age. Between 1200 BC and 1000 BC diffusion in the understanding of iron metallurgy and the use of iron objects was fast and far-flung. Anthony Snodgrass[15][16] suggests that a shortage of tin, as a part of the Bronze Age Collapse and trade disruptions in the Mediterranean around 1300 BC, forced metalworkers to seek an alternative to bronze. As evidence, many bronze implements were recycled into weapons during that time. More widespread use of iron led to improved steel-making technology at a lower cost. Thus, even when tin became available again, iron was cheaper, stronger and lighter, and forged iron implements superseded cast bronze tools permanently.[17]

Ancient Near East

The Iron Age in the Ancient Near East is believed to have begun with the discovery of iron smelting and smithing techniques in Anatolia or the Caucasus and Balkans in the late 2nd millennium BC (c. 1300 BC).[18] The earliest bloomery smelting of iron is found at Tell Hammeh, Jordan around 930 BC (determined from 14C dating).

The Early Iron Age in the Caucasus area is conventionally divided into two periods, Early Iron I, dated to around 1100 BC, and the Early Iron II phase from the tenth to ninth centuries BC. Many of the material culture traditions of the Late Bronze Age continued into the Early Iron Age. Thus, there is a sociocultural continuity during this transitional period.[19]

In Iran, the earliest actual iron artifacts were unknown until the 9th century BC.[20] For Iran, the best studied archaeological site during this time period is Teppe Hasanlu.

West Asia

In the Mesopotamian states of Sumer, Akkad and Assyria, the initial use of iron reaches far back, to perhaps 3000 BC.[21] One of the earliest smelted iron artifacts known was a dagger with an iron blade found in a Hattic tomb in Anatolia, dating from 2500 BC.[22] The widespread use of iron weapons which replaced bronze weapons rapidly disseminated throughout the Near East (North Africa, southwest Asia) by the beginning of the 1st millennium BC.

The development of iron smelting was once attributed to the Hittites of Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age. As part of the Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Age, the Bronze Age collapse saw the slow, comparatively continuous spread of iron-working technology in the region. It was long held that the success of the Hittite Empire during the Late Bronze Age had been based on the advantages entailed by the "monopoly" on ironworking at the time.[23] Accordingly, the invading Sea Peoples would have been responsible for spreading the knowledge through that region. The view of such a "Hittite monopoly" has come under scrutiny and no longer represents a scholarly consensus.[23] While there are some iron objects from Bronze Age Anatolia, the number is comparable to iron objects found in Egypt and other places of the same time period; and only a small number of these objects are weapons.[24]

| Finds of Iron | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

Egypt

The Iron Age in Egyptian archaeology essentially corresponds to the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt.

Iron metal is singularly scarce in collections of Egyptian antiquities. Bronze remained the primary material there until the conquest by Neo-Assyrian Empire in 671 BC. The explanation of this would seem to be that the relics are in most cases the paraphernalia of tombs, the funeral vessels and vases, and iron being considered an impure metal by the ancient Egyptians it was never used in their manufacture of these or for any religious purposes. It was attributed to Seth, the spirit of evil who according to Egyptian tradition governed the central deserts of Africa.[21] In the Black Pyramid of Abusir, dating before 2000 BC, Gaston Maspero found some pieces of iron. In the funeral text of Pepi I, the metal is mentioned.[21] A sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah as well as a battle axe with an iron blade and gold-decorated bronze shaft were both found in the excavation of Ugarit.[22] A dagger with an iron blade found in Tutankhamun's tomb, 13th century BC, was recently examined and found to be of meteoric origin.[26][27][28]

Europe

In Europe, the Iron Age is the last stage of prehistoric Europe and the first of the protohistoric periods, which initially means descriptions of a particular area by Greek and Roman writers. For much of Europe, the period came to an abrupt local end after conquest by the Romans, though ironworking remained the dominant technology until recent times. Elsewhere it may last until the early centuries AD, and either Christianization or a new conquest in the Migration Period.

Iron working was introduced to Europe in the late 11th century BC,[29] probably from the Caucasus, and slowly spread northwards and westwards over the succeeding 500 years. The Iron Age did not start when iron first appeared in Europe but it began to replace bronze in the preparation of tools and weapons.[30] It did not happen at the same time all around Europe; local cultural developments played a role in the transition to the Iron Age. For example, the Iron Age of Prehistoric Ireland begins around 500 BC (when the Greek Iron Age had already ended) and finishes around AD 400. The widespread use of the technology of iron was implemented in Europe simultaneously with Asia.[31] The prehistoric Iron Age in Central Europe divided into two periods based on historical events – Hallstatt culture (early Iron Age) and La Tène (late Iron Age) cultures.[32] Material cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène consist of 4 phases (A, B, C, D phases).[33][34][35]

| Phase A | Phase B | Phase C | Phase D | |

| Hallstatt | (1200–700 BC)

Flat graves |

(1200–700 BC)

Pottery made of polychrome |

(700–600 BC)

heavy iron and bronze swords |

(600–475 BC)

dagger swords, brooches, and ring ornaments, girdle mounts |

| La Tène | (450–390 BC)

s-shaped, spiral and round designs |

(390–300 BC)

Iron swords, heavy knives, lanceheads |

(300–100 BC)

iron chains, iron swords, belts, heavy spearheads |

(100–15 BC)

iron reaping-hooks, saws, scythes and hammers |

The Iron Age in Europe is characterized by an elaboration of designs in weapons, implements, and utensils.[21] These are no longer cast but hammered into shape, and decoration is elaborate and curvilinear rather than simple rectilinear; the forms and character of the ornamentation of the northern European weapons resemble in some respects Roman arms, while in other respects they are peculiar and evidently representative of northern art.[36]

Citania de Briterios located in Guimarães, Portugal is one of the examples of archaeological sites of the Iron Age. This settlement (fortified villages) covered an area of 3.8 hectares (9.4 acres), and served as a Celtiberian stronghold against Roman invasions. İt dates more than 2500 years back. The site was researched by Francisco Martins Sarmento starting from 1874. A number of amphoras (containers usually for wine or olive oil), coins, fragments of pottery, weapons, pieces of jewelry, as well as ruins of a bath and its pedra formosa (lit. 'handsome stone') revealed here.[37][38]

Asia

Central Asia

The Iron Age in Central Asia began when iron objects appear among the Indo-European Saka in present-day Xinjiang (China) between the 10th century BC and the 7th century BC, such as those found at the cemetery site of Chawuhukou.[39]

The Pazyryk culture is an Iron Age archaeological culture (c. 6th to 3rd centuries BC) identified by excavated artifacts and mummified humans found in the Siberian permafrost in the Altay Mountains.

East Asia

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

In China, Chinese bronze inscriptions are found around 1200 BC, preceding the development of iron metallurgy, which was known by the 9th century BC.[40][41] Therefore, in China prehistory had given way to history periodized by ruling dynasties by the start of iron use, so "Iron Age" is not typically used as to describe a period in Chinese history. Iron metallurgy reached the Yangtse Valley toward the end of the 6th century BC.[42] The few objects were found at Changsha and Nanjing. The mortuary evidence suggests that the initial use of iron in Lingnan belongs to the mid-to-late Warring States period (from about 350 BC). Important non-precious husi style metal finds include Iron tools found at the tomb at Guwei-cun of the 4th century BC.[43]

The techniques used in Lingnan are a combination of bivalve moulds of distinct southern tradition and the incorporation of piece mould technology from the Zhongyuan. The products of the combination of these two periods are bells, vessels, weapons and ornaments, and the sophisticated cast.

An Iron Age culture of the Tibetan Plateau has tentatively been associated with the Zhang Zhung culture described in early Tibetan writings.

Iron objects were introduced to the Korean peninsula through trade with chiefdoms and state-level societies in the Yellow Sea area in the 4th century BC, just at the end of the Warring States Period but before the Western Han Dynasty began.[44][45] Yoon proposes that iron was first introduced to chiefdoms located along North Korean river valleys that flow into the Yellow Sea such as the Cheongcheon and Taedong Rivers.[46] Iron production quickly followed in the 2nd century BC, and iron implements came to be used by farmers by the 1st century in southern Korea.[44] The earliest known cast-iron axes in southern Korea are found in the Geum River basin. The time that iron production begins is the same time that complex chiefdoms of Proto-historic Korea emerged. The complex chiefdoms were the precursors of early states such as Silla, Baekje, Goguryeo, and Gaya[45][47] Iron ingots were an important mortuary item and indicated the wealth or prestige of the deceased in this period.[48]

In Japan, iron items, such as tools, weapons, and decorative objects, are postulated to have entered Japan during the late Yayoi period (c. 300 BC–AD 300)[49] or the succeeding Kofun period (c. AD 250–538), most likely through contacts with the Korean Peninsula and China.

Distinguishing characteristics of the Yayoi period include the appearance of new pottery styles and the start of intensive rice agriculture in paddy fields. Yayoi culture flourished in a geographic area from southern Kyūshū to northern Honshū. The Kofun and the subsequent Asuka periods are sometimes referred to collectively as the Yamato period; The word kofun is Japanese for the type of burial mounds dating from that era.

South Asia

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

Iron was being used in Mundigak to manufacture some items in the 3rd millennium BC such as a small copper/bronze bell with an iron clapper, a copper/bronze rod with two iron decorative buttons,. and a copper/bronze mirror handle with a decorative iron button.[50] Artefacts including small knives and blades have been discovered in the Indian state of Telangana which have been dated between 2,400 BC and 1800 BC[51][52] The history of metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent began prior to the 3rd millennium BC. Archaeological sites in India, such as Malhar, Dadupur, Raja Nala Ka Tila, Lahuradewa, Kosambi and Jhusi, Allahabad in present-day Uttar Pradesh show iron implements in the period 1800–1200 BC.[10] As the evidence from the sites Raja Nala ka tila, Malhar suggest the use of Iron in c.1800/1700 BC. The extensive use of iron smelting is from Malhar and its surrounding area. This site is assumed as the center for smelted bloomer iron to this area due to its location in the Karamnasa River and Ganga River. This site shows agricultural technology as iron implements sickles, nails, clamps, spearheads, etc, by at least c.1500 BC.[53] Archaeological excavations in Hyderabad show an Iron Age burial site.[54]

The beginning of the 1st millennium BC saw extensive developments in iron metallurgy in India. Technological advancement and mastery of iron metallurgy were achieved during this period of peaceful settlements. One ironworking centre in East India has been dated to the first millennium BC.[55] In Southern India (present-day Mysore) iron appeared as early as 12th to 11th centuries BC; these developments were too early for any significant close contact with the northwest of the country.[55] The Indian Upanishads mention metallurgy.[56] and the Indian Mauryan period saw advances in metallurgy.[57] As early as 300 BC, certainly by AD 200, high-quality steel was produced in southern India, by what would later be called the crucible technique. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon.[58]

The protohistoric Early Iron Age in Sri Lanka lasted from 1000 BC to 600 BC. Radiocarbon evidence has been collected from Anuradhapura and Aligala shelter in Sigiriya.[59][60][61][62] The Anuradhapura settlement is recorded to extend 10 ha (25 acres) by 800 BC and grew to 50 ha (120 acres) by 700–600 BC to become a town.[63] The skeletal remains of an Early Iron Age chief were excavated in Anaikoddai, Jaffna. The name 'Ko Veta' is engraved in Brahmi script on a seal buried with the skeleton and is assigned by the excavators to the 3rd century BC. Ko, meaning "King" in Tamil, is comparable to such names as Ko Atan and Ko Putivira occurring in contemporary Brahmi inscriptions in south India.[64] It is also speculated that Early Iron Age sites may exist in Kandarodai, Matota, Pilapitiya and Tissamaharama.[65]

Southeast Asia

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

Archaeology in Thailand at sites Ban Don Ta Phet and Khao Sam Kaeo yielding metallic, stone, and glass artifacts stylistically associated with the Indian subcontinent suggest Indianization of Southeast Asia beginning in the 4th to 2nd centuries BC during the late Iron Age.[66]

In Philippines and Vietnam, the Sa Huynh culture showed evidence of an extensive trade network. Sa Huynh beads were made from glass, carnelian, agate, olivine, zircon, gold and garnet; most of these materials were not local to the region and were most likely imported. Han-Dynasty-style bronze mirrors were also found in Sa Huynh sites. Conversely, Sa Huynh produced ear ornaments have been found in archaeological sites in Central Thailand, as well as the Orchid Island.[67]: 211–217

Sub-Saharan Africa

In Sub-Saharan Africa, where there was no continent-wide universal Bronze Age, the use of iron immediately succeeded the use of stone.[21] Metallurgy was characterized by the absence of a Bronze Age, and the transition from stone to iron in tool substances. Early evidence for iron technology in Sub-Saharan Africa can be found at sites such as KM2 and KM3 in northwest Tanzania and parts of Nigeria and the Central African Republic. Nubia was one of the relatively few places in Africa to have a sustained Bronze Age along with Egypt and much of the rest of North Africa.

Very early copper and bronze working sites in Niger may date to as early as 1500 BC. There is also evidence of iron metallurgy in Termit, Niger from around this period.[11][68] Nubia was a major manufacturer and exporter of iron after the expulsion of the Nubian dynasty from Egypt by the Assyrians in the 7th century BC.[69]

Though there is some uncertainty, some archaeologists believe that iron metallurgy was developed independently in sub-Saharan West Africa, separately from Eurasia and neighboring parts of North and Northeast Africa.[70][71]

Archaeological sites containing iron smelting furnaces and slag have also been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria in what is now Igboland: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[14][71] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).[71] The site of Gbabiri (in the Central African Republic) has yielded evidence of iron metallurgy, from a reduction furnace and blacksmith workshop; with earliest dates of 896-773 BC and 907-796 BC respectively.[72] Similarly, smelting in bloomery-type furnaces appear in the Nok culture of central Nigeria by about 550 BC and possibly a few centuries earlier.[73][74][70][72]

Iron and copper working in Sub-Saharan Africa spread south and east from Central Africa in conjunction with the Bantu expansion, from the Cameroon region to the African Great Lakes in the 3rd century BC, reaching the Cape around AD 400.[11] However, iron working may have been practiced in Central Africa as early as the 3rd millennium BC.[75] Instances of carbon steel based on complex preheating principles were found to be in production around the 1st century AD in northwest Tanzania.[76]

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

Image gallery

- Iron Age Examples

Broborg Knivsta, prehistoric castle

Broborg Knivsta, prehistoric castle

See also

- Blast furnace

- Fogou

- Metallurgy in pre-Columbian America

- List of archaeological periods

- List of archaeological sites

- Roman metallurgy

References

- Milisauskas, Sarunas (ed), European Prehistory: A Survey, 2002, Springer, ISBN 0306467933, 9780306467936, google books

- (Karl von Rotteck, Karl Theodor Welcker, Das Staats-Lexikon (1864), p. 774

- Oriental Institute Communications, Issues 13–19, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 1922, p. 55.

- Rehren, Thilo; Belgya, Tamás; Jambon, Albert; Káli, György; Kasztovszky, Zsolt; Kis, Zoltán; Kovács, Imre; Maróti, Boglárka; Martinón-Torres, Marcos; Miniaci, Gianluca; Pigott, Vincent C.; Radivojević, Miljana; Rosta, László; Szentmiklósi, László; Szőkefalvi-Nagy, Zoltán (2013). "5,000 years old Egyptian iron beads made from hammered meteoritic iron" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (12): 4785–4792. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.002.

- Archaeomineralogy, p. 164, George Robert Rapp, Springer, 2002

- Understanding materials science, p. 125, Rolf E. Hummel, Springer, 2004

- James E. McClellan III; Harold Dorn (2006). Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8360-6. p. 21.

- Akanuma, Hideo (2008). "The Significance of Early Bronze Age Iron Objects from Kaman-Kalehöyük, Turkey" (PDF). Anatolian Archaeological Studies. Tokyo: Japanese Institute of Anatolian Archaeology. 17: 313–320.

- Souckova-Siegolová, J. (2001). "Treatment and usage of iron in the Hittite empire in the 2nd millennium BC". Mediterranean Archaeology. 14: 189–93.

- Tewari, Rakesh (2003). "The origins of Iron Working in India: New evidence from the Central Ganga Plain and the Eastern Vindhyas" (PDF). Antiquity. 77 (297): 536–545. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.4300. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00092590. S2CID 14951163.

- Duncan E. Miller and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Early Metal Working in Sub Saharan Africa' Journal of African History 35 (1994) 1–36; Minze Stuiver and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa' Current Anthropology 1968.

- How Old is the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa? – by Roderick J. McIntosh, Archaeological Institute of America (1999)

- Iron in Sub-Saharan Africa Archived 2 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine – by Stanley B. Alpern (2005)

- Eze–Uzomaka, Pamela. "Iron and its influence on the prehistoric site of Lejja". Academia.edu. University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- A.M.Snodgrass (1966), "Arms and Armour of the Greeks". (Thames & Hudson, London)

- A.M. Snodgrass (1971), "The Dark Age of Greece" (Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh).

- Theodore Wertime and J.D. Muhly, eds. The Coming of the Age of Iron (New Haven, 1979).

- Jane C. Waldbaum, From Bronze to Iron: The Transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean (Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology, vol. LIV, 1978).

- IRON AGE CAUCASIA. encyclopedia.com

- IRON AGE (Iran). iranicaonline.org

- Chisholm, H. (1910). The Encyclopædia Britannica. New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Co.

- Cowen, Richard (April 1999). "Chapter 5: The Age of Iron". Essays on Geology, History, and People. UC Davis. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018.

- Muhly, James D. 'Metalworking/Mining in the Levant' pp. 174–183 in Near Eastern Archaeology ed. Suzanne Richard (2003), pp. 179–180.

- Waldbaum, Jane C. From Bronze to Iron. Gothenburg: Paul Astöms Förlag (1978): 56–58.

- "Alex Webb, "Metalworking in Ancient Greece"". freeserve.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 December 2007.

- Comelli, Daniela; d'Orazio, Massimo; Folco, Luigi; El-Halwagy, Mahmud; et al. (2016). "The meteoritic origin of Tutankhamun's iron dagger blade". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 51 (7): 1301. Bibcode:2016M&PS...51.1301C. doi:10.1111/maps.12664.Free full text available.

-

Walsh, Declan (2 June 2016). "King Tut's Dagger Made of 'Iron From the Sky,' Researchers Say". The New York Times. NYC. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

...the blade’s composition of iron, nickel and cobalt was an approximate match for a meteorite that landed in northern Egypt. The result “strongly suggests an extraterrestrial origin"...

- Panko, Ben (2 June 2016). "King Tut's dagger made from an ancient meteorite". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- Riederer, Josef; Wartke, Ralf-B.: "Iron", Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.): Brill's New Pauly, Brill 2009

- "History of Europe – The Iron Age". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- John Collis, "The European Iron Age" (1989)

- "History of Europe – The chronology of the Metal Ages". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "La Tène | archaeological site, Switzerland". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Hallstatt | archaeological site, Austria". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Exploring The World of "The Celts". Thames and Hudson Ltd; 1st. Paperback Edition. 2005. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-500-27998-4.

- Ransone, Rob (21 October 2019). Genesis Too: A Rational Story of How All Things Began and the Main Events that Have Shaped Our World. Dorrance Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 9781644262375.

- Francisco Sande Lemos. "Citânia de Briteiros" (PDF). Translated by Andreia Cunha Silva. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- "Citânia de Briteiros" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Mark E. Hall, "Towards an absolute chronology for the Iron Age of Inner Asia," Antiquity 71.274 [1997], 863–874.

- Derevianki, A.P. 1973. Rannyi zheleznyi vek Priamuria

- Keightley, David N. (September 1983). The Origins of Chinese Civilization. University of California Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-520-04229-2.

- Higham, Charles (1996). The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56505-9.

- Encyclopedia of World Art: Landscape in art to Micronesian cultures. McGraw-Hill. 1964.

- Kim, Do-heon. 2002. Samhan Sigi Jujocheolbu-eui Yutong Yangsang-e Daehan Geomto [A Study of the Distribution Patterns of Cast Iron Axes in the Samhan Period]. Yongnam Kogohak [Yongnam Archaeological Review] 31:1–29.

- Taylor, Sarah. 1989. The Introduction and Development of Iron Production in Korea. World Archaeology 20(3):422–431.

- Yoon, Dong-suk. 1989. Early Iron Metallurgy in Korea. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 8(1):92–99.

- Barnes, Gina L. 2001. State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. Curzon, London.

- Lee, Sung-joo. 1998. Silla – Gaya Sahoe-eui Giwon-gwa Seongjang [The Rise and Growth of Silla and Gaya Society]. Hakyeon Munhwasa, Seoul.

- Keally, Charles T. (14 October 2002). "Prehistoric Archaeological Periods in Japan". Japanese Archaeology.

- "Metal Technologies of the Indus Valley Tradition in Pakistan and Western India" (PDF). www.harappa.com. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Rare discovery pushes back Iron Age in India - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Rao, Kp. "Iron Age in South India: Telangana and Andhra Pradesh".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ranjan, Amit (January 2014). "The Northern Black Painted Ware Culture Of Middle Ganga Plain: Recent Perspective". Manaviki.

- K. Venkateshwarlu (10 September 2008). "Iron Age burial site discovered". The Hindu.

- Early Antiquity By I.M. Drakonoff. 1991. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14465-8. p. 372

- Upanisads By Patrick Olivelle. Published in 1998. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283576-9. p. xxix

- The New Cambridge History of India By J.F. Richards, Gordon Johnson, Christopher Alan Bayly. 2005. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36424-8. p. 64

- Juleff, G. (1996), "An ancient wind-powered iron smelting technology in Sri Lanka", Nature, 379 (3): 60–63.

- Weligamage, Lahiru (2005). "The Ancient Sri Lanka". LankaLibrary Forum. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Deraniyagala, Siran, The Prehistory of Sri Lanka; an ecological perspective. (revised ed.), Colombo: Archaeological Survey Department of Sri Lanka, 1992: 709-29

- Karunaratne and Adikari 1994, Excavations at Aligala prehistoric site. In: Bandaranayake and Mogren (1994). Further studies in the settlement archaeology of the Sigiriya-Dambulla region. Sri Lanka, University of Kelaniya: Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology :58

- Mogren 1994. Objectives, methods, constraints, and perspectives. In: Bandaranayake and Mogren (1994) Further studies in the settlement archaeology of the Sigiriya-Dambulla region. Sri Lanka, University of Kelaniya: Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology: 39.

- F.R. Allchin 1989. City and State Formation in Early Historic South Asia. South Asian Studies 5:1-16: 3

- Indrapala, K. The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 324

- Deraniyagala, Siran, The Prehistory of Sri Lanka; an ecological perspective. (revised ed.), Colombo: Archaeological Survey Department of Sri Lanka, 1992: 730–732, 735

- Glover, I.C.; Bellina, B. (2011). "Ban Don Ta Phet and Khao Sam Kaeo: The Earliest Indian Contacts Re-assessed". Early Interactions between South and Southeast Asia. Vol. 2. pp. 17–45. doi:10.1355/9789814311175-005. ISBN 978-981-4345-10-1.

- Higham, C., 2014, Early Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok: River Books Co., Ltd., ISBN 978-616-7339-44-3

- Iron in Africa: Revising the History, UNESCO Aux origines de la métallurgie du fer en Afrique, Une ancienneté méconnue: Afrique de l'Ouest et Afrique centrale.

- Collins, Rober O. and Burns, James M. The History of Sub-Saharan Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 37. ISBN 978-0-521-68708-9.

- Eggert, Manfred (2014). "Early iron in West and Central Africa". In Breunig, P (ed.). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt, Germany: Africa Magna Verlag Press. pp. 51–59.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (6 November 2009). "Early West African Metallurgies: New Data and Old Orthodoxy". Journal of World Prehistory. 22 (4): 415–438. doi:10.1007/s10963-009-9030-6. S2CID 161611760.

- Eggert, Manfred (2014). "Early iron in West and Central Africa". In Breunig, P (ed.). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt, Germany: Africa Magna Verlag Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 9783937248462.

- Duncan E. Miller and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Early Metal Working in Sub Saharan Africa' Journal of African History 35 (1994) 1-36

- Minze Stuiver and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa' Current Anthropology 1968. Tylecote 1975 (see below)

- Pringle, Heather (9 January 2009). "Seeking Africa's first Iron Men". Science. 323 (5911): 200–202. doi:10.1126/science.323.5911.200. PMID 19131604. S2CID 206583802.

- Peter Schmidt, Donald H. Avery. Complex Iron Smelting and Prehistoric Culture in Tanzania, Science 22 September 1978: Vol. 201. no. 4361, pp. 1085–1089

Further reading

| Library resources about Iron Age |

- Jan David Bakker, Stephan Maurer, Jörn-Steffen Pischke and Ferdinand Rauch. 2021. "Of Mice and Merchants: Connectedness and the Location of Economic Activity in the Iron Age." Review of Economics and Statistics 103 (4): 652–665.

- Chang, Claudia. Rethinking Prehistoric Central Asia: Shepherds, Farmers, and Nomads. New York: Routledge, 2018.

- Collis, John. The European Iron Age. London: B.T. Batsford, 1984.

- Cunliffe, Barry W. Iron Age Britain. Rev. ed. London: Batsford, 2004.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine, V. A Bashilov, and L. Tiablonskiĭ. Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age. Berkeley, CA: Zinat Press, 1995.

- Finkelstein, Israel, and Eli Piasetzky. "The Iron Age Chronology Debate: Is the Gap Narrowing?" Near Eastern Archaeology 74.1 (2011): 50–55.

- Jacobson, Esther. Burial Ritual, Gender, and Status in South Siberia in the Late Bronze–Early Iron Age. Bloomington: Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, 1987.

- Mazar, Amihai. "Iron Age Chronology: A Reply to I. Finkelstein". Levant 29 (1997): 157–167.

- Mazar, Amihai. "The Iron Age Chronology Debate: Is the Gap Narrowing? Another Viewpoint". Near Eastern Archaeology 74.2 (2011): 105–110.

- Medvedskaia, I. N. Iran: Iron Age I. Oxford: B.A.R., 1982.

- Shinnie, P. L. The African Iron Age. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971.

- Tripathi, Vibha. The Age of Iron in South Asia: Legacy and Tradition. New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2001.

- Waldbaum, Jane C. From Bronze to Iron: The Transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean. Göteborg: P. Aström, 1978.

External links

- General

- A site with a focus on Iron Age Britain from resourcesforhistory.com

- Human Timeline (Interactive)—Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- Publications

- Andre Gunder Frank and William R. Thompson, Early "Iron Age economic expansion and contraction revisited". American Institute of Archaeology, San Francisco, January 2004.

- News

- "Mass burial suggests massacre at Iron Age hill fort". Archaeologists have found evidence of a massacre linked to Iron Age warfare at a hill fort in Derbyshire. BBC. 17 April 2011