Transjordan (region)

Transjordan, the East Bank,[1] or the Transjordanian Highlands (Arabic: شرق الأردن), is the part of the Southern Levant east of the Jordan River, mostly contained in present-day Jordan.

The region, known as Transjordan, was controlled by numerous powers throughout history. During the early modern period, the region of Transjordan was included under the jurisdiction of Ottoman Syrian provinces. After the Great Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule during the 1910s, the Emirate of Transjordan was established in 1921 by Hashemite Emir Abdullah, and the Emirate became a British protectorate. In 1946, the Emirate achieved independence from the British and in 1949 the country changed its name to the "Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan", after the Jordanian annexation of the West Bank following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.

Name

The prefix trans- is Latin and means "across" or beyond, and so "Transjordan" refers to the land on the other side of the Jordan River. The equivalent term for the west side is the Cisjordan – literally, "on this side of the [River] Jordan".

The Tanakh's Hebrew: בעבר הירדן מזרח השמש, romanized: be·êv·er hay·yar·dên miz·raḥ hash·shê·mesh, lit. 'beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise',[2] is translated in the Septuagint[3] to Ancient Greek: πέραν τοῦ Ιορδάνου,, romanized: translit. péran toú Iordánou,, lit. 'beyond the Jordan', which was then translated to Latin: trans Iordanen, lit. 'beyond the Jordan' in the Vulgate Bible. However some authors give the Hebrew: עבר הירדן, romanized: Ever HaYarden, lit. 'beyond the Jordan', as the basis for Transjordan, which is also the modern Hebrew usage.[4] Whereas the term "East" as in "towards the sunrise" is used in Arabic: شرق الأردن, romanized: Sharq al ʾUrdun, lit. 'East of the Jordan'.

History

Egyptian period

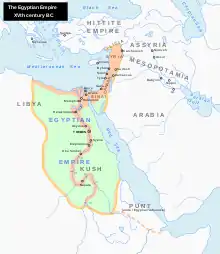

The Shasu were Semitic-speaking cattle nomads in the Levant from the late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age. In a 15th-century BCE list of enemies inscribed on column bases at the temple of Soleb built by Amenhotep III, six groups of Shasu are noted; the Shasu of S'rr, the Shasu of Rbn, the Shasu of Sm't, the Shasu of Wrbr, the Shasu of Yhw, and the Shasu of Pysps. Some scholars link the Israelites and the worship of a deity named Yahweh with the Shasu.

The Egyptian geographical term "Retjenu", is traditionally identified as an area covering Sinai and Canaan south of Lebanon,[5] with the regions of Amurru and Apu to the north.[6] And as such, parts of Canaan and southwestern Syria became tributary to the Egyptian Pharaohs in the early Late Bronze Age. When Canaanite confederacies centered on Megiddo and Kadesh, came under the control of the Egyptian Empire. However, the empire's control was sporadic, and not strong enough to prevent frequent local rebellions and inter-city conflict.

Bronze Age collapse

During the Late Bronze Age collapse the Amorites of Syria disappeared after being displaced or absorbed by a new wave of semi-nomadic West Semitic-speaking peoples known collectively as the Ahlamu. Over time, the Arameans emerged as the dominant tribe amongst the Ahlamu; with the destruction of the Hittites and the decline of Assyria in the late 11th century BCE, they gained control over much of Syria and Transjordan. The regions they inhabited became known as Aram (Aramea) and Eber-Nari.

The Transjordanian Hebrew tribes

The Book of Numbers (chapter 32) tells how the tribes of Reuben and Gad came to Moses to ask if they could settle in the Transjordan. Moses is dubious, but the two tribes promise to join in the conquest of the land, and so Moses grants them this region to live in. The half tribe of Manasseh are not mentioned until verse 33. David Jobling suggests that this is because Manasseh settled in land which previously belonged to Og, north of the Jabbok, while Reuben and Gad settled Sihon's land, which lay south of the Jabbok. Since Og's territory was not on the route to Canaan, it was "more naturally part of the Promised Land", and so the Manassites' status is less problematic than that of the Reubenites or Gadites.[7]

In the Book of Joshua (1), Joshua affirms Moses' decision, and urges the men of the two and a half tribes to help in the conquest, which they are willing to do. In Joshua 22, the Transjordanian tribes return, and build a massive altar by the Jordan. This causes the "whole congregation of the Israelites" to prepare for war, but they first send a delegation to the Transjordanian tribes, accusing them of making God angry and suggesting that their land may be unclean. In response to this, the Transjordanian tribes say that the altar is not for offerings, but is only a "witness". The western tribes are satisfied, and return home. Assis argues that the unusual dimensions of the altar suggest that it "was not meant for sacrificial use", but was, in fact, "meant to attract the attention of the other tribes" and provoke a reaction.[8]

Per the settlement of the Israelite tribes east of the Jordan, Burton MacDonald notes;

There are various traditions behind the Books of Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, and 1 Chronicles’ assignment of tribal territories and towns to Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh. Some of these traditions provide only an idealized picture of Israelite possessions east of the Jordan; others are no more than vague generalizations. Num 21.21–35, for example, says only that the land the people occupied extended from Wadi Arnon to Wadi Jabbok, the boundary of the Amorites.[9]

Status

There is some ambiguity about the status of the Transjordan in the mind of the biblical writers. Horst Seebass argues that in Numbers "one finds awareness of Transjordan as being holy to YHWH."[11] He argues for this on the basis of the presence of the cities of refuge there, and because land taken in a holy war is always holy. Richard Hess, on the other hand, asserts that "the Transjordanian tribes were not in the land of promise."[12] Moshe Weinfeld argues that in the Book of Joshua, the Jordan is portrayed as "a barrier to the promised land",[10] but in Deuteronomy 1:7 and 11:24, the Transjordan is an "integral part of the promised land."[13]

Unlike the other tribal allotments, the Transjordanian territory was not divided by lot. Jacob Milgrom suggests that it is assigned by Moses rather than by God.[14]

Lori Rowlett argues that in the Book of Joshua, the Transjordanian tribes function as the inverse of the Gibeonites (mentioned in Joshua 9). Whereas the former have the right ethnicity, but wrong geographical location, the latter have the wrong ethnicity, but are "within the boundary of the 'pure' geographical location."[15]

Other Transjordanian nations

According to Genesis, (19:37–38), Ammon and Moab were born to Lot and Lot's younger and elder daughters, respectively, in the aftermath of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. The Bible refers to both the Ammonites and Moabites as the "children of Lot". Throughout the Bible, the Ammonites and Israelites are portrayed as mutual antagonists. During the Exodus, the Israelites were prohibited by the Ammonites from passing through their lands (Deuteronomy 23:4). In the Book of Judges, the Ammonites work with Eglon, king of the Moabites against Israel. Attacks by the Ammonites on Israelite communities east of the Jordan were the impetus behind the unification of the tribes under Saul (1 Samuel 11:1–15).

According to both Books of Kings (14:21–31) and Books of Chronicles (12:13), Naamah was an Ammonite. She was the only wife of King Solomon to be mentioned by name in the Tanakh as having borne a child. She was the mother of Solomon's successor, Rehoboam.[16]

The Ammonites presented a serious problem to the Pharisees because many marriages with Ammonite (and Moabite) wives had taken place in the days of Nehemiah (Nehemiah 13:23). The men had married women of the various nations without conversion, which made the children not Jewish.[17] The legitimacy of David's claim to royalty was disputed on account of his descent from Ruth, the Moabite.[18] King David spent time in the Transjordan after he had fled from the rebellion of his son Absalom (2 Samuel 17–19).

Classical period

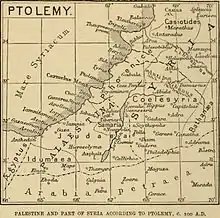

The Decapolis is named from its ten cities enumerated by Pliny the Elder (23–79). What Pliny calls Decapolis, Ptolemy (c. 100–c. 170) calls Cœle-Syria.[19] Ptolemy does not use the term "Transjordan", but rather the periphrasis "across the Jordan".[20] And he enumerates the cities; Cosmas, Libias, Callirhoe, Gazorus, Epicaeros—as being in this district—east of the Jordan, that Josephus et al. called Perea.[21][22][23][24]

Jerash was a prominent central community for the surrounding region during the Neolithic period[25] and was also inhabited during the Bronze Age. Ancient Greek inscriptions from the city, and the literary works of Iamblichus and the Etymologicum Magnum indicate that the city was founded as "Gerasa" by Alexander the Great or his general Perdiccas, for the purpose of settling retired Macedonian soldiers (γῆρας—gēras—means "old age" in Ancient Greek). It was a city of the Decapolis, and is one of the most important and best preserved Ancient Roman cities in the Near East.

The Nabataeans' trading network was centered on strings of oases that they controlled. The Nabataean kingdom reached its territorial zenith during the reign of Aretas III (87-62 BCE), when it encompassed parts of the territory of modern Jordan, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Israel.

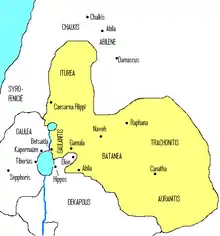

Bosra is located in a geographical area called the Hauran plateau. The soil of this volcanic plateau made it a fertile region for the cultivation of domesticated cereals during the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution. The city was noted in Egyptian documents of the 14th century BCE, and was situated on the trade routes where caravans brought spices from India and the Far East across the eastern desert while other caravans brought myrrh and frankincense from the south. The region of Hauran then called "Auranitis" came under the control of the Nabataean kingdom. And the city of Bosra then called "Bostra" became the northern capital of the kingdom while its southern capital was Petra. After Pompey's military conquest of Syria, Judaea, and Transjordan. Control of the city was later transferred to Herod the Great and his heirs until 106 CE, when Bosra was incorporated into the new Roman province of Arabia Petraea.

The Herodian kingdom of Judaea was a client state of the Roman Republic from 37 BCE, and included Samaria and Perea. And when Herod died in 4 BCE, the kingdom was divided among his sons into the Herodian Tetrarchy.

Provincia Arabia Petraea or simply Arabia, was a frontier province of the Roman Empire beginning in the 2nd century. It consisted of the former Nabataean kingdom in the southern Levant, Sinai Peninsula, and northwestern Arabian peninsula.

Crusader period: Oultrejordain

The Lordship of Oultrejordain (Old French for "beyond the Jordan"), also called the Lordship of Montreal, otherwise Transjordan, was part of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Trade routes

- Via Maris

- Via Traiana Nova

- Petra Roman Road

The King's Highway was a trade route of vital importance to the ancient Near East. It began in Egypt and stretched across the Sinai Peninsula to Aqaba. From there it turned northward across Transjordan, leading to Damascus and the Euphrates River. During the Roman period the road was called Via Regia (Orient). Emperor Trajan rebuilt and renamed it Via Traiana Nova (viz. Via Traiana Roma), under which name it served as a military and trade road along the fortified Limes Arabicus.

The Incense Route comprised a network of major ancient land and sea trading routes linking the Mediterranean world with Eastern and Southern sources of incense, spices and other luxury goods, stretching from Mediterranean ports across the Levant and Egypt through Northeastern Africa and Arabia to India and beyond. The incense land trade from South Arabia to the Mediterranean flourished between roughly the 7th century BCE to the 2nd century CE.

Maps

- BCE

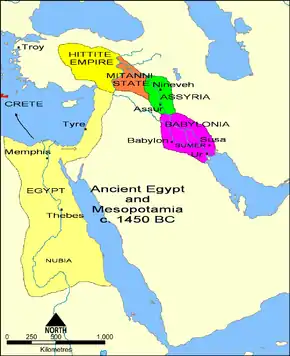

New Kingdom at its maximum territorial extent in the 15th century BCE

New Kingdom at its maximum territorial extent in the 15th century BCE

.jpg.webp) Near East 1300 BCE

Near East 1300 BCE.jpg.webp) Near East 1000 BCE

Near East 1000 BCE Transjordan Kingdoms of Ammon, Edom and Moab during the Iron Age 830 BCE

Transjordan Kingdoms of Ammon, Edom and Moab during the Iron Age 830 BCE

- CE

The British Mandate for Palestine. The Emirate of Transjordan is shown in brown.

The British Mandate for Palestine. The Emirate of Transjordan is shown in brown. Jordan, 1948–1967. The East Bank is the portion east of the Jordan River, the West Bank is the part west of the river

Jordan, 1948–1967. The East Bank is the portion east of the Jordan River, the West Bank is the part west of the river Countries pictured are (clockwise from top right) Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Egypt (across the Gulf of Aqaba), Israel, the disputed West Bank Territory, and Lebanon. In the center is Jordan.

Countries pictured are (clockwise from top right) Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Egypt (across the Gulf of Aqaba), Israel, the disputed West Bank Territory, and Lebanon. In the center is Jordan.

- Trade routes

Levantine trade routes 1300 BCE

Levantine trade routes 1300 BCE

- Egyptian Empire

The Hanigalbat (Mitanni) and Egypt.

The Hanigalbat (Mitanni) and Egypt.

Map of the Ancient Near East during the Amarna Period.

Map of the Ancient Near East during the Amarna Period.

- Transjordan Kingdoms 830 BCE

Transjordan Kingdoms during the Iron Age 830 BCE

Transjordan Kingdoms during the Iron Age 830 BCE

- Persian period and Diadochi period

- Roman Orient

- Roman Empire

Network of primary Roman roads in the reign of Hadrian

Network of primary Roman roads in the reign of Hadrian

See also

- The East Bank of the Jordan

- Emirate of Transjordan

- Geography of Jordan

- Gilead

- Oultrejordain

- Perea (region)

- Transjordan in the Bible, an area of land in the Southern Levant lying east of the Jordan River that is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible

- Transjordan memorandum

References

- N. Orpett (2012). "The Archaeology of Land Law: Excavating Law in the West Bank". International Journal of Legal Information. 40 (3): 344–391. doi:10.1017/S0731126500011410. S2CID 150542926.

- "Joshua 1:15". Hebrew Bible. Trowitzsch. 1892. p. 155.

בעבר הירדן מזרח השמש (text at http://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt0601.htm)

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - "Joshua 1:15". The Septuagint Version of the Old Testament, with an English translation; and with various readings and critical notes. Gr. & Eng. S. Bagster & Sons. 1870. p. 281.

Image of p. 281 at Google Books

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - Merrill, Selah (1881). East of the Jordan: A Record of Travel and Observation in the Countries of Moab, Gilead and Bashan. C. Scribner's sons. p. 444.

Image of p. 444 at Google Books

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - Ryholt, K. S. B.; Bülow-Jacobsen, Adam (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt During the Second Intermediate Period, C. 1800-1550 B.C. Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-87-7289-421-8.

- Bryce, Trevor (15 March 2012). The World of The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms: A Political and Military History. OUP Oxford. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-19-150502-7.

Damascus’ history extends well back before the Aramaean occupation. It is first attested as one of the cities and kingdoms which fought against and were defeated by the pharaoh Tuthmosis III at the battle of Megiddo during Tuthmosis' first Asiatic campaign in 1479 (ANET 234-8). Henceforth, it appears in Late Bronze Age texts as the centre of a region called Aba/Apa/Apina/Upi/Upu [Apu]. From Tuthmosis' conquest onwards, for the remainder of the Late Bronze Age, this region remained under Egyptian sovereignty, though for a short time after the battle of Qadesh, fought in 1274 by the pharaoh Ramesses 11 against the Hittite king Muwatalli II, it came under Hittite control. After the Hittite withdrawal, Damascus and its surrounding region marked part of Egypt’s northern frontier with the Hittites.

- David Jobling, The Sense of Biblical Narrative II: Structural Analyses in the Hebrew Bible (JSOTSup. 39; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1986) 116.

- Elie Assis, "For it shall be a witness between us: a literary reading of Josh 22," Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 18 (2004) 216.

- MacDonald, Burton (2000). "Settlement of the Israelite Tribes East of the Jordan". In Matthews, Victor (ed.). EAST OF THE JORDAN: Territories and Sites of the Hebrew Scriptures (PDF). American Schools of Oriental Research. p. 149. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-01. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- Moshe Weinfeld, The Promise of the Land: The Inheritance of the Land of Canaan by the Israelites (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 54.

- Horst Seebass, "Holy Land in the Old Testament: Numbers and Joshua," Vetus Testamentum 56 (2006) 104.

- Richard S. Hess, "Tribes of Israel and Land Allotments/Borders," in Bill T. Arnold and H. G. M. Williamson (eds.), Dictionary of the Old Testament Historical Books (Downers Grove: IVP, 2005), 970.

- Moshe Weinfeld, "The Extent of the Promised Land – the Status of Transjordan," in Das Land Israel in biblischer Zeit (ed. G. Strecker; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1983) 66-68.

- Jacob Milgrom, Numbers (JPS Torah Commentary; Philadelphia: JPS, 1990), 74.

- Lori Rowlett, "Inclusion, Exclusion and Marginality in the Book of Joshua," JSOT 55 (1992) 17.

- "Naamah". Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906. Retrieved 2014-08-10.

- The identity of those particular tribes had been lost during the mixing of the nations caused by the conquests of Assyria. As a result, people from those nations were treated as complete gentiles and could convert without restriction.

- The Babylonian Talmud points out that Doeg the Edomite was the source of this dispute. He claimed that since David was descended from someone who was not allowed to marry into the community, his male ancestors were no longer part of the tribe of Judah (which was the tribe the King had to belong to). As a result, he could neither be the king, nor could he marry any Jewish woman (since he descended from a Moabite convert). The Prophet Samuel wrote the Book of Ruth in order to remind the people of the original law that women from Moab and Ammon were allowed to convert and marry into the Jewish people immediately.

- Hodgson, James; Derham, William; Mead, Richard; M. de Fontenelle (Bernard Le Bovier) (1727). Miscellanea Curiosa: Containing a Collection of Some of the Principal Phænomena in Nature, Accounted for by the Greatest Philosophers of this Age: Being the Most Valuable Discourses, Read and Delivered to the Royal Society, for the Advancement of Physical and Mathematical Knowledge. As Also a Collection of Curious Travels, Voyages, Antiquities, and Natural Histories of Countries; Presented to the Same Society. To which is Added, A Discourse of the Influence of the Sun and Moon on Human Bodies, &c. W. B. pp. 175–176.

Decapolis was so called from its ten Cities enumerated by Pliny (lib. 5. 18.) And with them he reckons up among others, the Tetrarchy of Abila in the same Decapolis : Which demonstrates the Abila Decapolis and Abila Lysaniæ to be the same Place. And tho'it cannot be denied, but that some of Pliny's ten Cities are not far distant from that near Jordan ; yet it doth not appear that ever this other had the Title of a Tetrarchy. Here it is to be observed, that what Pliny calls Decapolis, Ptolemy makes his Cœle-Syria ; and the Cœle-Syria of Pliny, is that Part of Syria about Aleppo, formerly call'd Chalcidene, Cyrrhistice, &c. (Image of p. 175 & p. 176 at Google Books)

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - Smith, William (1873). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. J. Murray. p. 533.

[Ptolemy] describes the Peraea by a periphrasis as the eastern side of Jordan which may imply that the name [Peraea] was no longer in vogue. (Image of p. 533 at Google Books)

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - Ptolemy, Geographica, Book 5, Ch.15:6

- Taylor, Joan E. (30 January 2015). The Essenes, the Scrolls, and the Dead Sea. Oxford University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-19-870974-9.

Ptolemy’s Geographica provided a great compendium of knowledge in terms of the placements of cities and lands in the ancient world, information that would form the basis of medieval cartography, resulting in a standard Ptolemaic map of Asia, including Palestine. The information about Judaea appears in Book 5, where pars Asphatitem lacum are mentioned as well as the main cities. In the region east of the Jordan, there are sites that are not all easy to determine: Cosmas, Libias, Callirhoe, Gazorus, Epicaeros (Ptolemy, Geogr. 5: 15: 6).

- Jones, A. H. M. (30 June 2004). "Appendix 2. Ptolemy". The Cities of the Eastern Roman Provinces, 2nd Edition. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 500. ISBN 978-1-59244-748-0.

Ptolemy’s divisions of Palestine (v. xv) appear to follow popular lines. They are Galilee, Samaria, Judaea (with a subdivision ‘across the Jordan’), and Idumaea. These divisions were also for the most part, as Josephus’ survey of Palestine (Bell., III. iii. 1-5, §§ 35-57) shows, official. Josephus, however, does not recognize Idumaea, merging it in Iudaea, and definitely distinguishes Peraea from Judaea. Had Ptolemy derived his divisions from an official source, he would probably have followed this scheme, and in particular would have used the official term Peraea instead of the periphrasis ‘across the Jordan’.

- Cohen, Getzel M. (3 September 2006). The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa. University of California Press. p. 284, n. 1. ISBN 978-0-520-93102-2.

The problem of indicating precise ancient boundaries in Transjordan is difficult and complex and varies according to the time period under discussion. After the creation of the Roman province of Arabia in 106 A.D. Gerasa and Philadelphia were included in it. Nonetheless, Ptolemy—who was writing in the second century A.D. but did not record places by Roman provinces—described them as being in (the local geographical unit of) Coele Syria (5.14.18). Furthermore, Philadelphia continued to describe itself on its coins and in inscriptions of the second and third centuries A.D. as being a city of Coele Syria; see above, Philadelphia, n. 9. As for the boundaries of the new province, the northern frontier extended to a little beyond the north of Bostra and east; the western border ran somewhat east of the Jordan River valley and the Dead Sea but west of the city of Madaba (see M. Sartre, Trois ét., 17-75; Bowersock, ZPE5, [1970] 37-39; id., JRS61 [1971] 236-42; and especially id.. Arabia, 90-109). Gadara in Peraea is identified today with es-Salt near Tell Jadur, a place that is near the western boundary of the province of Arabia. And this region could have been described by Stephanos as being located ”between Coele Syria and Arabia.”

- Dana Al Emam (15 August 2015). "Two human skulls dating back to Neolithic period unearthed in Jerash". The Jordan Times. Retrieved 4 July 2016.