Asser

Asser (/ˈæsər/; Welsh: [ˈasɛr]; died c. 909) was a Welsh monk from St David's, Dyfed, who became Bishop of Sherborne in the 890s. About 885 he was asked by Alfred the Great to leave St David's and join the circle of learned men whom Alfred was recruiting for his court. After spending a year at Caerwent because of illness, Asser accepted.

Asser | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Sherborne | |

| See | Sherborne |

| Appointed | c. 895 |

| Term ended | c. 909 |

| Predecessor | Wulfsige |

| Successor | Æthelweard |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | c. 895 |

| Personal details | |

| Died | c. 909 |

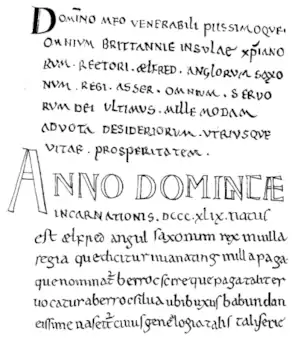

In 893, Asser wrote a biography of Alfred, called the Life of King Alfred. The manuscript survived to modern times in only one copy, which was part of the Cotton library. That copy was destroyed in a fire in 1731, but transcriptions that had been made earlier, together with material from Asser's work which was included by other early writers, have enabled the work to be reconstructed. The biography is the main source of information about Alfred's life and provides far more information about Alfred than is known about any other early English ruler. Asser assisted Alfred in his translation of Gregory the Great's Pastoral Care, and possibly with other works.

Asser is sometimes cited as a source for the legend about Alfred's having founded the University of Oxford, which is now known to be false. A short passage making this claim was interpolated by William Camden into his 1603 edition of Asser's Life. Doubts have also been raised periodically about whether the entire Life is a forgery, written by a slightly later writer, but it is now almost universally accepted as genuine.

Name and early life

Asser (also known as John Asser or Asserius Menevensis)[1] was a Welsh monk who lived from at least AD 885 until about 909. Almost nothing is known of Asser's early life. The name Asser is likely to have been taken from Aser, or Asher, the eighth son of Jacob in Genesis. Old Testament names were common in Wales at the time, but it has been suggested that this name may have been adopted at the time Asser entered the church. Asser may have been familiar with a work by St Jerome on the meaning of Hebrew names (Jerome's given meaning for "Asser" was "blessed").

According to his Life of King Alfred, Asser was a monk at St David's in what was then the kingdom of Dyfed, in south-west Wales. Asser makes it clear that he was brought up in the area, and was tonsured, trained and ordained there. He also mentions Nobis, a bishop of St David's who died in 873 or 874, as being a kinsman of his.[2]

Recruitment by Alfred and time at court

Much of what is known about Asser comes from his biography of Alfred, in particular a short section in which Asser recounts how Alfred recruited him as a scholar for his court. Alfred held a high opinion of the value of learning and recruited men from around Britain and from continental Europe to establish a scholarly centre at his court. It is not known how Alfred heard of Asser, but one possibility relates to Alfred's overlordship of south Wales. Several kings, including Hywel ap Rhys of Glywysing and Hyfaidd of Dyfed (where Asser's monastery was), had submitted to Alfred's overlordship in 885. Asser gives a fairly detailed account of the events. There is a charter of Hywel's which has been dated to c. 885; amongst the witnesses is one "Asser", which may be the same person. Hence it is possible that Alfred's relationship with the southern Welsh kings led him to hear of Asser.[2]

Asser recounts meeting Alfred first at the royal estate at Dean, Sussex (now East and West Dean, West Sussex).[3] Asser provides only one datable event in his history: on St Martin's Day, 11 November 887, Alfred decided to learn to read Latin. Working backwards from this, it appears most likely that Asser was recruited by Alfred in early 885.[2]

Asser's response to Alfred's request was to ask for time to consider the offer, as he felt it would be unfair to abandon his current position in favour of worldly recognition. Alfred agreed but also suggested that he should spend half his time at St David's and half with Alfred. Asser again asked for time to consider, but ultimately agreed to return to Alfred with an answer in six months. On his return to Wales, however, Asser fell ill with a fever and was confined to the monastery of Caerwent for twelve months and a week. Alfred wrote to find out the cause of the delay, and Asser responded that he would keep his promise when he recovered. When he did recover, in 886, he agreed to divide his time between Wales and Alfred's court, as Alfred had suggested. Others at St David's supported this, since they hoped Asser's influence with Alfred would avoid "damaging afflictions and injuries at the hands of King Hyfaidd (who often assaulted that monastery and the jurisdiction of St David)".[2][4]

Asser joined several other noted scholars at Alfred's court, including Grimbald, and John the Old Saxon; all three probably reached Alfred's court within a year of each other.[5] His first extended stay with Alfred was at the royal estate at Leonaford, probably from about April through December 886. It is not known where Leonaford was; a case has been made for Landford, in Wiltshire. Asser records that he read aloud to the king from the books at hand. On Christmas Eve, 886, after Asser had for some time failed to obtain permission to return to Wales, Alfred gave Asser the monasteries of Congresbury and Banwell, along with a silk cloak and a quantity of incense "weighing as much as a stout man." He allowed Asser to visit his new possessions and thence to return to St David's.[2][6]

Thereafter Asser seems to have divided his time between Wales and Alfred's court. Asser gives no information about his time in Wales, but mentions various places that he visited in England, including the battlefield at Ashdown, Cynuit (Countisbury), and Athelney. It is evident from Asser's account that he spent a good deal of time with Alfred: he recounts meeting Alfred's mother-in-law, Eadburh (who is not the same Eadburh who died as a beggar in Pavia), on many occasions; and says that he has often seen Alfred hunting.[2]

Bishop of Sherborne

Sometime between 887 and 892, Alfred gave Asser the monastery of Exeter. Asser subsequently became Bishop of Sherborne,[7] though the year of succession is unknown. Asser's predecessor as Bishop of Sherborne, Wulfsige, attested a charter in 892. Asser's first appearance in the position is in 900, when he appears as a witness to a charter; hence the succession can only be dated to the years 892 to 900.[8] In any event, Asser had already been a bishop prior to his appointment to the see of Sherborne, since Wulfsige is known to have received a copy of Alfred's Pastoral Care in which Asser is described as a bishop.[2]

It is possible that Asser was a suffragan bishop within the see of Sherborne, but he may instead have been a bishop of St David's. He is listed as such in Giraldus Cambrensis's Itinerarium Cambriae, although this may be unreliable as it was written three centuries later, in 1191. A contemporary clue is found in Asser's own writing: he mentions that bishops of St David's were sometimes expelled by King Hyfaidd and adds that "he even expelled me on occasion." This also implies that Asser was himself a bishop of St David's.[2]

The Life of King Alfred

In 893, Asser wrote a biography of Alfred entitled The Life of King Alfred; in the original Latin, the title is Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum. The date is known from Asser's mention of the king's age in the text. The work, which is less than twenty thousand words long, is one of the most important sources of information on Alfred the Great.[2][9]

Asser drew on a variety of texts to write his Life. The style is similar to that of two biographies of Louis the Pious: Vita Hludovici Imperatoris, written c. 840 by an unknown author usually called "the Astronomer", and Vita Hludowici Imperatoris by Thegan of Trier. It is possible that Asser may have known these works. He also knew Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum; the Historia Brittonum, a Welsh source; the Life of Alcuin; and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It is also clear from the text that Asser was familiar with Virgil's Aeneid, Caelius Sedulius's Carmen Paschale, Aldhelm's De Virginitate, and Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni ("Life of Charlemagne"). He quotes from Gregory the Great's Regula Pastoralis, a work he and Alfred subsequently collaborated in translating, and from Augustine of Hippo's Enchiridion. About half of the Life is little more than a translation of part of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the years 851–887, though Asser adds personal opinions and interpolates information about Alfred's life. Asser also adds material relating to the years after 887 and general opinions about Alfred's character and reign.[2][10]

Asser's prose style has been criticised for weak syntax, stylistic pretensions, and garbled exposition. His frequent use of archaic and unusual words gives his prose a baroque flavour that is common in Insular Latin authors of the period. He uses several words that are peculiar to Frankish Latin sources. This has led to speculation that he was educated at least partly in Francia, but it is also possible that he acquired this vocabulary from Frankish scholars he associated with at court, such as Grimbald.[2]

The Life ends abruptly with no concluding remarks and it is considered likely that the manuscript is an incomplete draft. Asser lived a further fifteen or sixteen years and Alfred a further six, but no events after 893 are recorded.[2]

It is possible that the work was written principally for the benefit of a Welsh audience. Asser takes pains to explain local geography, so he was clearly considering an audience not familiar with the areas he described. More specifically, at several points he gives an English name and follows it with the British / Welsh equivalent name, such as in the case of Nottingham. As a result, and given that Alfred's overlordship of south Wales was recent, it may be that Asser intended the work to acquaint a Welsh readership with Alfred's personal qualities and reconcile them to his rule.[2] However, it is also possible that Asser's inclusion of Welsh placenames simply reflects an interest in etymology or the existence of a Welsh audience in his own household rather than in Wales. There are also sections such as the support for Alfred's programme of fortification that give the impression of the book's being aimed at an English audience.[11]

Asser's Life omits any mention of internal strife or dissent in Alfred's own reign, though when he mentions that Alfred had to harshly punish those who were slow to obey Alfred's commands to fortify the realm, he makes it clear that Alfred did have to enforce obedience. Asser's life is a one-sided treatment of Alfred, though since Alfred was alive when it was composed, it is unlikely to contain gross errors of fact.[12][13]

In addition to being the primary source for Alfred's life, Asser's work is also a source for other historical periods, where he adds material to his translation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. For example, he tells a story about Eadburh, the daughter of Offa. Eadburh married Beorhtric, king of the West Saxons. Asser describes her as behaving "like a tyrant" and ultimately accidentally poisoning Beorhtric in an attempt to murder someone else. He finishes by describing her death as a beggar in Pavia.[14][15] This Eadburh is not the same as Alfred's mother-in-law, also named Eadburh, whom Asser mentions elsewhere.

Manuscripts of The Life of King Alfred

The early manuscript of the Life does not appear to have been widely known in medieval times. Only one copy is known to have survived into modern times. It is known as Cotton MS Otho A xii, and was part of the Cotton library. It was written about 1000 and was destroyed in a fire in 1731. The lack of distribution may be because Asser had not finished the manuscript and so did not have it copied. However, the material in the Life is recognizable in other works. There is some evidence from early writers of access to versions of Asser's work, as follows:[17]

- Byrhtferth of Ramsey included large sections of it into Historia Regum, a historical work he wrote in the late tenth or early 11th century. He may have used the Cotton manuscript. (The Historia Regum was until recently attributed to Symeon of Durham.)

- The anonymous author of the Encomium Emmae (written in the early 1040s) was apparently acquainted with the Life, though it is not known how he knew of it. The author was a monk of St Bertin's in Flanders, but may have learned of the work in England.

- The chronicler known as Florence of Worcester incorporated parts of Asser's Life into his chronicle, in the early 12th century; again, he may have also used the Cotton manuscript.

- An anonymous chronicler at Bury St Edmunds, working in the second quarter of the 12th century, produced a compilation now known as The Annals of St Neots. He used material from a version of Asser's work which differs in some places from the Cotton manuscript and in some places appears to be more accurate, so it is possible that the copy used was not the Cotton manuscript.

- Giraldus Cambrensis wrote a Life of St Æthelberht, probably at Hereford during the 1190s. He quotes an incident from Asser that occurred during the reign of Offa of Mercia, who died in 796. This incident is not in the surviving copies of the manuscript. It is possible that Giraldus had access to a different copy of Asser's work. It is also possible that he is quoting a different work by Asser, which is otherwise unknown, or even that Giraldus is making up the reference to Asser to support his story. The latter is at least plausible, since Giraldus is not always regarded as a trustworthy writer.

The history of the Cotton manuscript itself is quite complex. The list of early writers above mentions that it may have been in the possession of at least two of them. It was owned by John Leland, the antiquary, in the 1540s. It probably became available after the dissolution of the monasteries, in which the property of many religious houses was confiscated and sold. Leland died in 1552 and it is known to have been in the possession of Matthew Parker from some time after that until his own death in 1575. Although Parker bequeathed most of his library to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, the Cotton manuscript was not included. By 1600, it was in the library of Lord Lumley and by 1621 the manuscript was in the possession of Robert Cotton. The Cotton library was moved in 1712 from Cotton House in Westminster to Essex House in the Strand and then moved again in 1730 to Ashburnham House in Westminster. On the morning of Saturday, 23 October 1731, a fire broke out and the Cotton manuscript was destroyed.[17]

As a result, the text of Asser's Life is known from a multitude of different sources. Various transcripts had been made of the Cotton manuscript and a facsimile of the first page of the manuscript had been made and published, giving more direct evidence for the hand of the scribe. In addition to these transcripts, the extracts mentioned above made by other early writers have been used to help assemble and assess the text. Because of the lack of the manuscript itself and because Parker's annotations had been copied by some transcribers as if they were part of the text, scholarly editions have had a difficult burden. There have been multiple editions of The Life published, both in Latin and in translation.[17] The 1904 critical edition (with 130 pages of introduction) by W. H. Stevenson, Asser's Life of King Alfred, together with the Annals of Saint Neots erroneously ascribed to Asser, still provides the standard Latin text:[18] this was translated into English in 1905 by Albert S. Cook.[19][20] An important recent translation, with thorough notes on the scholarly problems and issues, is Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and Other Contemporary Sources by Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge.[21]

Legend of founding of Oxford

In 1603 the antiquarian William Camden published an edition of Asser's Life in which there appears a story of a community of scholars at Oxford, who were visited by Grimbald:

In the year of our Lord 886, the second year of the arrival of St Grimbald in England, the University of Oxford was begun ... John, monk of the church of St David, giving lectures in logic, music and arithmetic; and John, the monk, colleague of St Grimbald, a man of great parts and a universal scholar, teaching geometry and astronomy before the most glorious and invincible King Alfred.[22]

There is no support for this in any source known. Camden based his edition on Parker's manuscript, other transcripts of which do not include any such material. It is now acknowledged that this is an interpolation of Camden's, though the legend itself first surfaced in the 14th century.[1][23] Older books about Alfred the Great include the legend: for example, Jacob Abbott's 1849 Alfred the Great says that "One of the greatest and most important of the measures which Alfred adopted for the intellectual improvement of his people was the founding of the great University of Oxford."[24]

Claims of forgery

During the 19th and 20th centuries, several scholars asserted that Asser's biography of King Alfred was not authentic, but a forgery. A prominent claim was made in 1964 by the respected historian V.H. Galbraith in his essay "Who Wrote Asser's Life of Alfred?" Galbraith argued that there were anachronisms in the text that meant it could not have been written during Asser's lifetime. For example, Asser uses "rex Angul Saxonum" ("king of the Anglo-Saxons") to refer to Alfred. Galbraith asserted that this usage does not appear until the late 10th century. Galbraith also identified the use of "parochia" to refer to Exeter as an anachronism, arguing that it should be translated as "diocese" and hence that it referred to the bishopric of Exeter, which was not created until 1050. Galbraith identified the true author as Leofric, who became Bishop of Devon and Cornwall in 1046. Leofric's motive, according to Galbraith, was to justify the re-establishment of his see at Exeter by demonstrating a precedent for the arrangement.[2][25]

The title "king of the Anglo-Saxons" does, however, in fact occur in royal charters that date to before 892 and "parochia" does not necessarily mean "diocese", but can sometimes refer just to the jurisdiction of a church or monastery. In addition, there are other arguments against Leofric's having been the forger. Aside from the fact that Leofric would have known little about Asser and so would have been unlikely to construct a plausible forgery, there is strong evidence dating the Cotton manuscript to about 1000. The apparent use of Asser's material in other early works that predate Leofric also argues against Galbraith's theory. Galbraith's arguments were refuted to the satisfaction of most historians by Dorothy Whitelock in Genuine Asser, in the Stenton Lecture of 1967.[26][2][25]

More recently, in 2002, Alfred Smyth has argued that the Life is a forgery by Byrhtferth, basing his case primarily on an analysis of Byrhtferth's and Asser's Latin vocabulary. Byrhtferth's motive, according to Smyth, is to lend Alfred's prestige to the Benedictine monastic reform movement of the late tenth century. However, the argument has not been found persuasive, and few historians harbour doubts about the authenticity of the work.[2][25][27]

Other works and date of death

In addition to the Life of King Alfred, Asser is credited by Alfred as one of several scholars who assisted with Alfred's translation of Pope Gregory I's Regula Pastoralis (Pastoral Care). The historian William of Malmesbury, writing in the 12th century, believed that Asser also assisted Alfred with his translation of Boethius.[28]

The Annales Cambriae, a set of Welsh annals that were probably kept at St David's, records Asser's death in the year 908. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the following entry as part of the entry for 909 or 910 (in different versions of the chronicle): "Here Frithustan succeeded to the bishopric in Winchester, and after that Asser, who was bishop at Sherborne, departed."[29] The year given by the chronicle was uncertain, because different chroniclers started the new year at different calendar dates, and Asser's date of death is generally given as 908/909.[2]

References

- A'Becket, John Joseph (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge, Alfred the Great, pp. 48–58, 93–96, and 220–221.

- John McNeil Dodgson. Place-Names in Sussex in Brandons. South Saxons. Ch. IV. p. 71

- Asser tells the story of his recruitment in chapter 79 of his Life of King Alfred (Keynes & Lapidge, Alfred the Great, pp. 93–94).

- Keynes and Lapidge, Alfred the Great, pp. 26–27.

- The story of Asser's first visit to Alfred's court is taken from chapter 81 of his Life (Keynes & Lapidge, Alfred the Great, p. 96).

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology, p. 222

- Keynes & Lapidge, Alfred the Great, pp. 49, 181

- Gallagher, Robert (2021). "Asser and the Writing of West Saxon Charters*". The English Historical Review. 136 (581): 773–808. doi:10.1093/ehr/ceab276. ISSN 0013-8266.

- Abels, Alfred the Great, pp. 13–14.

- Campbell, The Anglo-Saxon State, p. 142.

- Fletcher, Richard (1989). Who's Who in Roman Britain and Anglo-Saxon England. Shepheard-Walwyn. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-85683-089-1.

- Asser's biases and how to interpret them are discussed in detail in Campbell, The Anglo-Saxon State, pp. 145–150.

- Campbell, John; John, Eric; Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. Penguin Books. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-14-014395-9.

- Keynes and Lapidge, Alfred the Great, pp. 71–72.

- Abels, Alfred the Great, p. 319.

- Keynes and Lapidge, Alfred the Great, pp. 223–227.

- Stevenson, William Henry (1904). Asser's Life of King Alfred: together with the Annals of Saint Neots erroneously ascribed to Asser (in Latin and English). Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Cook, Albert S. (1905). Asser's Life of King Alfred, translated from the text of Stevenson's edition. Boston: Ginn and Company. p. 1.

- Abels, Alfred the Great, p. 328.

- Richard Abels (Alfred the Great, p. 328) describes Keynes and Lapidge's book as "The best collection of primary sources in translation", and "an indispensable guide to the scholarly problems and issues surrounding these works".

- "Oxford Figures – About: The Mathematical Institute, University of Oxford". Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- See for example The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21): Volume I. From the Beginnings to the Cycles of Romance. Chapter VI: Alfred and the Old English Prose of his Reign, § 1: Asser's Life of Alfred is online at "§1. Asser's "Life of Alfred". VI. Alfred and the Old English Prose of his Reign. Vol. 1. From the Beginnings to the Cycles of Romance". Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- "The Baldwin Project: Alfred the Great by Jacob Abbott". Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- See "On the Authenticity of Asser's Life of King Alfred" in Abels, Alfred the Great, pp. 321–324. Pages 319–321 review Galbraith's argument, and the academic response; 321–324 cover Smyth.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1968). Genuine Asser (PDF). University of Reading. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Smyth, Alfred P. (2002). The Medieval Life of King Alfred the Great. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-69917-1. Smyth's book is also available online.

- Abels, Alfred the Great, p. 11.

- Swanton, Michael (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Routledge. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-415-92129-9.

Sources

- Asser, Asser’s Life of King Alfred, ed. William H. Stevenson, with an article by Dorothy Whitelock (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1957). Standard edition of the Latin original.

- Abels, Richard (2005). Alfred the Great: War, Kingship and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-04047-2.

- Brandon, Peter, ed. (1978). The South Saxons. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 978-0-85033-240-7.

- Campbell, James (2000). The Anglo-Saxon State. Hambledon and London. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-85285-176-7.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56350-5.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (2004). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources. New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

External links

- Asser 1 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- HTML full text of Asser's Life of King Alfred (English translation)

- Asser's Life of Alfred, commentary from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Volume I, 1907–21.

- Asser's Life of Alfred

- Works by or about Asser at Internet Archive

- Works by Asser at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)