Asturian language

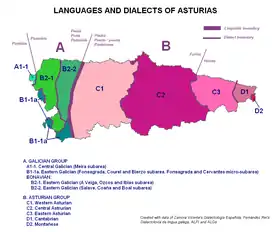

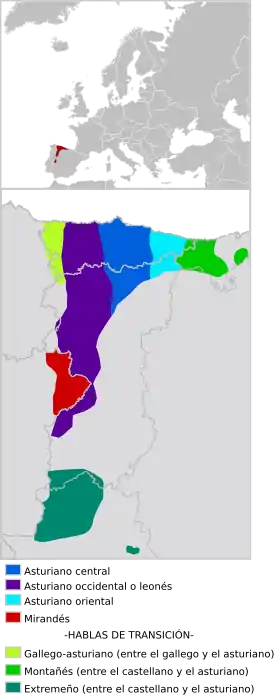

Asturian (/æˈstʊəriən/; asturianu [astuˈɾjanʊ],[4] formerly also known as bable [ˈbaβlɪ]) is a West Iberian Romance language spoken in the Principality of Asturias, Spain.[5] Asturian is part of a wider linguistic group, the Asturleonese languages. The number of speakers is estimated at 100,000 (native) and 450,000 (second language).[6] The dialects of the Astur-Leonese language family are traditionally classified in three groups: Western, Central, and Eastern. For historical and demographic reasons, the standard is based on Central Asturian. Asturian has a distinct grammar, dictionary, and orthography. It is regulated by the Academy of the Asturian Language. Although it is not an official language of Spain[7] it is protected under the Statute of Autonomy of Asturias and is an elective language in schools.[8] For much of its history, the language has been ignored or "subjected to repeated challenges to its status as a language variety" due to its lack of official status.[9]

| Asturian | |

|---|---|

| asturianu | |

| Native to | Spain |

| Region | Asturias |

| Ethnicity | Asturians |

Native speakers | Around 1/3 of Asturians[1] (2000) 62% of Asturians[2] (2017) |

Indo-European

| |

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Academia de la Llingua Asturiana |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | ast |

| ISO 639-3 | ast |

| Glottolog | astu1245 |

| ELP | Asturian |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-ca |

| IETF | ast-u-sd-esas |

Linguistic area of Astur-Leonese, including Asturian | |

History

Asturian is the historical language of Asturias, portions of the Spanish provinces of León and Zamora and the area surrounding Miranda do Douro in northeastern Portugal.[10] Like the other Romance languages of the Iberian peninsula, it evolved from Vulgar Latin during the early Middle Ages. Asturian was closely linked with the Kingdom of Asturias (718–910) and the ensuing Leonese kingdom. The language had contributions from pre-Roman languages spoken by the Astures, an Iberian Celtic tribe, and the post-Roman Germanic languages of the Visigoths and Suevi.

The transition from Latin to Asturian was slow and gradual; for a long time they co-existed in a diglossic relationship, first in the Kingdom of Asturias and later in that of Asturias and Leon. During the 12th, 13th and part of the 14th centuries Astur-Leonese was used in the kingdom's official documents, with many examples of agreements, donations, wills and commercial contracts from that period onwards. Although there are no extant literary works written in Asturian from this period, some books (such as the Llibru d'Alexandre and the 1155 Fueru d'Avilés)[11][12] had Asturian sources.

Castilian Spanish arrived in the area during the 14th century, when the central administration sent emissaries and functionaries to political and ecclesiastical offices. Asturian codification of the Astur-Leonese spoken in the Asturian Autonomous Community became a modern language with the founding of the Academy of the Asturian Language (Academia Asturiana de la Llingua) in 1980. The Leonese dialects and Mirandese are linguistically close to Asturian.

Status and legislation

Efforts have been made since the end of the Francoist period in 1975 to protect and promote Asturian.[13] In 1994 there were 100,000 native speakers and 450,000[14] second-language speakers able to speak (or understand) Asturian.[15] However the language is endangered: there has been a steep decline in the number of speakers over the last century. Law 1/93 of 23 March 1993 on the Use and Promotion of the Asturian Language addressed the issue, and according to article four of the Asturias Statute of Autonomy:[4] "The Asturian language will enjoy protection. Its use, teaching and diffusion in the media will be furthered, whilst its local dialects and voluntary apprenticeship will always be respected.”

However Asturian is in a legally hazy position. The Spanish Constitution has not been fully applied regarding the official recognition of languages in the autonomous communities. The ambiguity of the Statute of Autonomy, which recognises the existence of Asturian but does not give it the same status as Spanish, leaves the door open to benign neglect. However since 1 August 2001 Asturian has been covered under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages' "safeguard and promote" clause.[3]

A 1983 survey[16] indicated 100,000 native Asturian speakers (12 percent of the Asturian population) and 250,000 who could speak or understand Asturian as a second language. A similar survey in 1991 found that 44 percent of the population (about 450,000 people) could speak Asturian, with from 60,000 to 80,000 able to read and write it. An additional 24 percent of the Asturian population said that they understood the language, making a total of about 68 percent of the Asturian population.[17]

At the end of the 20th century the Academia de la Llingua Asturiana (Academy of the Asturian Language) attempted to provide the language with tools needed to promote its survival: a grammar, a dictionary and periodicals. In addition a new generation of Asturian writers has championed the language. In 2021 the first complete translation of the Bible into Asturian was published.[18]

Historical, social and cultural aspects

Literary history

Although some 10th-century documents have the linguistic features of Asturian, numerous examples (such as writings by notaries, contracts and wills) begin in the 13th century.[19][20] Early examples are the 1085 Fuero de Avilés (the oldest parchment preserved in Asturias)[21] and the 13th-century Fuero de Oviedo and the Leonese version of the Fueru Xulgu.

The 13th-century documents were the laws for towns, cities and the general population.[20] By the second half of the 16th century, documents were written in Castilian, backed by the Trastámara dynasty and making the civil and ecclesiastical arms of the principality Castilian. Although the Asturian language disappeared from written texts during the sieglos escuros (dark centuries), it survived orally. The only written mention during this time is from a 1555 work by Hernán Núñez about proverbs and adages: " ... in a large copy of rare languages, as Portuguese, Galician, Asturian, Catalan, Valencian, French, Tuscan ... ".[22]

Modern Asturian literature began in 1605 with the clergyman Antón González Reguera and continued until the 18th century (when it produced, according to Ruiz de la Peña in 1981, a literature comparable to that in Asturias in Castilian).[23] In 1744, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos wrote about the historic and cultural value of Asturian, urging the compilation of a dictionary and a grammar and the creation of a language academy. Notable writers included Francisco Bernaldo de Quirós Benavides (1675), Xosefa Xovellanos (1745), Xuan González Villar y Fuertes (1746), Xosé Caveda y Nava (1796), Xuan María Acebal (1815), Teodoro Cuesta (1829), Xosé Benigno García González, Marcos del Torniello (1853), Bernardo Acevedo y Huelves (1849), Pin de Pría (1864), Galo Fernández and Fernán Coronas (1884).

In 1974, a movement for the language's acceptance and use began in Asturias. Based on ideas of the Asturian association Conceyu Bable about Asturian language and culture, a plan was developed for the acceptance and modernization of the language that led to the 1980 creation of the Academy of the Asturian Language with the approval of the Asturias regional council. El Surdimientu (the Awakening) authors such as Manuel Asur (Cancios y poemes pa un riscar), Xuan Bello (El llibru vieyu), Adolfo Camilo Díaz (Añada pa un güeyu muertu), Pablo Antón Marín Estrada (Les hores), Xandru Fernández (Les ruines), Lourdes Álvarez, Martín López-Vega, Miguel Rojo and Lluis Antón González broke from the Asturian-Leonese tradition of rural themes, moral messages and dialogue-style writing. Currently, the Asturian language has about 150 annual publications.[24] The Bible into the Asturian language was completed in 2021 after over 30 years of translation work, beginning in September 1988.[18]

Use and distribution

Astur-Leonese's geographic area exceeds Asturias, and that the language known as Leonese in the autonomous community of Castile and León is basically the same as the Asturian spoken in Asturias. The Asturian-Leonese linguistic domain covers most of the principality of Asturias, the northern and western province of León, the northeastern province of Zamora (both in Castile and León), western Cantabria and the Miranda do Douro region in the eastern Bragança District of Portugal.

Toponymy

Traditional, popular place names of the principality's towns are supported by the law on usage of Asturian, the principality's 2003–07 plan for establishing the language[25] and the work of the Xunta Asesora de Toponimia,[26] which researches and confirms the Asturian names of requesting villages, towns, conceyos and cities (50 of 78 conceyos as of 2012).

Dialects

Asturian has several dialects. They are regulated by the Academia de la Llingua Asturiana and mainly spoken in Asturias (except in the west, where Galician-Asturian is spoken). The dialect spoken in the adjoining area of Castile and León is known as Leonese. Asturian is traditionally divided into three dialectal areas, sharing traits with the dialect spoken in León:[19] western, central and eastern. The dialects are mutually intelligible. Central Asturian, with the most speakers (more than 80 percent), is the basis for standard Asturian. The first Asturian grammar was published in 1998 and the first dictionary in 2000.

Western Asturian is spoken between the rivers Navia and Nalón, in the west of the province of León (where it is known as Leonese) and in the provinces of Zamora and Salamanca. Feminine plurals end in -as and the falling diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/ are maintained.

Central Asturian is spoken between the Sella River and the mouth of the River Nalón in Asturias and north of León. The model for the written language, it is characterized by feminine plurals ending in -es, the monophthongization of /ou/ and /ei/ into /o/ and /e/ and the neuter gender[27] in adjectives modifying uncountable nouns (lleche frío, carne tienro).

Eastern Asturian is spoken between the River Sella, Llanes and Cabrales. The dialect is characterized by the debuccalization of word-initial /f/ to [h], written ⟨ḥ⟩ (ḥoguera, ḥacer, ḥigos and ḥornu instead of foguera, facer, figos and fornu; feminine plurals ending in -as (ḥabas, ḥormigas, ḥiyas, except in eastern towns, where -es is kept: ḥabes, ḥormigues, ḥiyes); the shifting of word-final -e to -i (xenti, tardi, ḥuenti); retention of the neutral gender[27] in some areas, with the ending -u instead of -o (agua friu, xenti güenu, ropa tendíu, carne guisáu), and a distinction between direct and indirect objects in first- and second-person singular pronouns (direct me and te v. indirect mi and ti) in some municipalities bordering the Sella: busquéte (a ti) y alcontréte/busquéti les llaves y alcontrétiles, llévame (a mi) la fesoria en carru.

Asturian forms a dialect continuum with Cantabrian in the east and Eonavian in the west. While this dialect continuum is for the most part smooth, a number of isoglosses cluster together parallel to the River Purón, linking the dialects of eastern Llanes, Ribadedeva, Peñamellera Alta, and Peñamellera Baja with those of Cantabria and separating them from the rest of Asturias.[28] Cantabrian was listed in the 2009 UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[29] The inclusion of Eonavian (spoken in western Asturias, bordering Galicia) in the Galician language is controversial, since it has traits in common with western Asturian.

Linguistic description

Asturian is one of the Astur-Leonese languages which form part of the Iberian Romance languages, close to Galician-Portuguese and Castilian and further removed from Navarro-Aragonese. It is an inflecting, fusional, head-initial and dependent-marking language. Its word order is subject–verb–object (in declarative sentences without topicalization).

Vowels

Asturian distinguishes five vowel phonemes (these same ones are found in Spanish, Aragonese, Sardinian and Basque), according to three degrees of vowel openness (close, mid and open) and backness (front, central and back). Many Asturian dialects have a system of metaphony.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

- When occurring as unstressed, close vowels /i u/ can become glides as [j w] in the pre-nuclear position. In the post-nuclear syllable margin, they are traditionally heard and transcribed as non-syllabic vowels [i̯ u̯].[30]

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | |

| voiced | b | d | ʝ | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f | θ | s | ʃ | ||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Tap | ɾ | |||||

- /b, d, ɡ/ may be lenited or sonorized as [β, ð, ɣ] in certain environments, or word-initially.

- /n/ is pronounced [ŋ] in coda position.

- /ʝ/ can have different pronunciations, as a voiced plosive [ɟ], affricate [ɟ͡ʝ], or as a voiced fricative [ʝ].

Writing

Asturian has always been written in the Latin alphabet. Although the Academia de la Llingua Asturiana published orthographic rules in 1981,[31] different spelling rules are used in Terra de Miranda (Portugal).

Asturian orthography is based on a five-vowel system (/a e i o u/), with three aperture degrees. It has the following consonants: /p t tʃ k b d ʝ ɡ f θ s ʃ m n ɲ l ʎ r ɾ/. The phenomenon of -u metaphony is uncommon, as are decrescent diphthongs (/ei, ou/, usually in the west). Although they can be written, ḷḷ (che vaqueira, formerly represented as "ts") and the eastern ḥ aspiration (also represented as "h." and corresponding to ll and f) are absent from this model. Asturian has triple gender distinction in the adjective, feminine plurals with -es, verb endings with -es, -en, -íes, íen and lacks compound tenses[31] (or periphrasis constructed with "tener").

Alphabet

| Uppercase | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | L | M | N | Ñ | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | l | m | n | ñ | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | x | y | z |

| Name | a | be | ce | de | e | efe | gue | hache | i | ele | eme | ene | eñe | o | pe | cu | erre | ese | te | u | uve | xe | ye(*) | zeta (**) |

| Phoneme | /a/ | /b/ | /θ/, /k/ | /d/ | /e/ | /f/ | /ɣ/ | – | /i/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ | /ɲ/ | /o/ | /p/ | /k/ | /r/, /ɾ/ | /s/ | /t/ | /u/ | /b/ | /ʃ/ | /ʝ/ | /θ/ |

- (*) also y griega

- (*) also zeda

Digraphs

Asturian has several digraphs, some of which have their own names.

| Digraph | Name | Phoneme |

|---|---|---|

| ch | che | /t͡ʃ/ |

| gu (+ e, i) | (gue u) | /ɡ/ |

| ll | elle | /ʎ/ |

| qu (+ e, i) | (cu u) | /k/ |

| rr | erre doble | /r/ |

| ts | (te ese) | /t͡s/ (dialectal) |

| yy | (ye doble) | /ɟ͡ʝ/ (dialectal) |

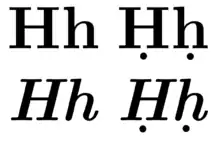

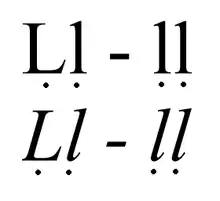

Dialectal spellings

The letter h and the digraph ll can have their sound changed to represent dialectal pronunciation by under-dotting the letters, resulting in ḥ and digraph ḷḷ

| Normal | Pronunciation | Dotted | Pronunciation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ll | /ʎ/ | ḷḷ | /t͡s/, /ɖʐ/, /ɖ/ and /ʈʂ/ | ḷḷeite, ḷḷinu |

| h | – | ḥ | /h/, /x/ | ḥou, ḥenu, ḥuera |

- The "ḥ" is common in eastern Asturian place names and in words beginning with f;[32] workarounds such as h. and l.l were used in the past for printing.

Grammar

Asturian grammar is similar to that of other Romance languages. Nouns have three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter), two numbers (singular and plural) and no cases. Adjectives may have a third, neuter gender, a phenomenon known as matter-neutrality.[32] Verbs agree with their subjects in person (first, second, or third) and number, and are conjugated to indicate mood (indicative, subjunctive, conditional or imperative; some others include "potential" in place of future and conditional),[32] tense (often present or past; different moods allow different tenses), and aspect (perfective or imperfective).[32]

Gender

Asturian is the only western Romance language with three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter.

- Masculine nouns usually end in -u, sometimes in -e or a consonant: el tiempu (time, weather), l’home (man), el pantalón (trousers), el xeitu (way, mode).

- Feminine nouns usually end in -a, sometimes -e: la casa (house), la xente (people), la nueche (night).

- Neuter nouns may have any ending. Asturian has three types of neuters:

- Masculine neuters have a masculine form and take a masculine article: el fierro vieyo (old iron).

- Feminine neuters have a feminine form and take a feminine article: la lleche frío (cold milk).

- Pure neuters are nominal groups with an adjective and neuter pronoun: lo guapo d’esti asuntu ye... (the interesting [thing] about this issue is ...).

Adjectives are modified by gender. Most adjectives have three endings: -u (masculine), -a (feminine) and -o (neuter): El vasu ta fríu (the glass is cold), tengo la mano fría (my hand is cold), l’agua ta frío (the water is cold)

Neuter nouns are abstract, collective and uncountable nouns. They have no plural, except when they are used metaphorically or concretised and lose this gender: les agües tán fríes (Waters are cold). Tien el pelo roxo (He has red hair) is neuter, but Tien un pelu roxu (He has a red hair) is masculine; note the noun's change in ending.

Number

Plural formation is complex:

- Masculine nouns ending in -u → -os: texu (yew) → texos.

- Feminine nouns ending in -a → -es: vaca (cow) → vaques.

- Masculine or feminine nouns ending in a consonant take -es: animal (animal) → animales; xabón (soap) → xabones.

- Words ending in -z may take a masculine -os to distinguish them from the feminine plural: rapaz (boy) → rapazos; rapaza (girl) → rapaces.

- Masculine nouns ending in -ín → -inos: camín (way, path) → caminos, re-establishing the etymological vowel.

- Feminine nouns ending in -á, -ada, -ú → -aes or -úes, also re-establishing the etymological vowel: ciudá (city) → ciudaes; cansada (tired [feminine]) → cansaes; virtú (virtue) → virtúes.

Determiners

Their forms are:

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

*Only before words beginning with a-: l’aigla (the eagle), l’alma (the soul). Compare la entrada (the entry) and la islla (the island).

Resources

The Academy of the Asturian Language has published a grammar describing the Asturian language.[32] It is a comprehensive manual that can be used in schools to facilitate learning.

Additionally, a translator that can translate English, French, Portuguese and Italian, among a few other languages, into Asturian and vice versa is offered online.[33] This software is funded and maintained by members of the University of Oviedo.[33]

Vocabulary

As with other Romance languages, most Asturian words come from Latin: ablana, agua, falar, güeyu, home, llibru, muyer, pesllar, pexe, prau, suañar. In addition to this Latin basis are words which entered Asturian from languages spoken before the arrival of Latin (its substratum), afterwards (its superstratum) and loanwords from other languages.

Substratum

Although little is known about the language of the ancient Astures, it may have been related to two Indo-European languages: Celtic and Lusitanian. Words from this language and the pre–Indo-European languages spoken in the region are known as the prelatinian substratum; examples include bedul, boroña, brincar, bruxa, cándanu, cantu, carrascu, comba, cuetu, güelga, llamuerga, llastra, llócara, matu, peñera, riega, tapín and zucar. Many Celtic words (such as bragues, camisa, carru, cerveza and sayu) were integrated into Latin and, later, into Asturian.

Superstratum

Asturian's superstratum consists primarily of Germanisms and Arabisms. The Germanic peoples in the Iberian Peninsula, especially the Visigoths and the Suevi, added words such as blancu, esquila, estaca, mofu, serón, espetar, gadañu and tosquilar. Arabisms could reach Asturian directly, through contacts with Arabs or al-Andalus, or through the Castilian language. Examples include acebache, alfaya, altafarra, bañal, ferre, galbana, mandil, safase, xabalín, zuna and zucre.

Loanwords

Asturian has also received much of its lexicon from other languages, such as Spanish, French, Occitan and Galician. In number of loanwords, Spanish leads the list. However, due to the close relationship between Castilian and Asturian, it is often unclear if a word is borrowed from Castilian, common to both languages from Latin, or a loanword from Asturian to Castilian. Some Castilian forms in Asturian are:

| Latin[34] | Galician[35] | Asturian[36] | Spanish |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diphthongization of Ŏ & Ĕ | |||

| PŎRTA(M) (door) | porta | puerta | puerta |

| ŎCULU(M) (eye) | ollo | güeyu güechu |

ojo |

| TĔMPUS, TĔMPŎR- (time) | tempo | tiempu | tiempo |

| TĔRRA(M) (land) | terra | tierra | tierra |

| F- (initial position) | |||

| FACĔRE (to do) | facer | facer(e) | hacer |

| FĔRRU(M) (iron) | ferro | fierru | hierro |

| L- (initial position) | |||

| [[lares|LARE(M)]] (home) | lar | llar ḷḷar |

lar |

| LŬPU(M) (wolf) | lobo | llobu ḷḷobu |

lobo |

| N- (initial position) | |||

| NATIVITĀTE(M) (Christmas) | nadal | nadal ñavidá |

navidad |

| Palatalization of PL-, CL-, FL- | |||

| PLĀNU(M) (plane) | chan | ḷḷanu llanu |

llano |

| CLĀVE(M) (key) | chave | ḷḷave llave |

llave |

| FLĂMMA(M) (flame) | chama | ḷḷama llama |

llama |

| Rising diphthongs | |||

| CAUSA(M) (cause) | cousa | co(u)sa | cosa |

| FERRARĬU(M) (smith) | ferreiro | ferre(i)ru | herrero |

| Palatalization of -CT- & -LT- | |||

| FĂCTU(M) (fact) | feito | feitu fechu |

hecho |

| NŎCTE(M) (night) | noite | nueite nueche |

noche |

| MŬLTU(M) (much) | muito | muncho | mucho |

| AUSCULTĀRE (to listen) | escoitar | escuchar | escuchar |

| Group -M'N- | |||

| HŎMINE(M) (man) | home | home | hombre |

| FĂME(M) (hunger, famine) | fame | fame | hambre |

| LŪMEN, LŪMĬN- (fire) | lume | llume ḷḷume |

lumbre |

| -L- intervocalic | |||

| GĔLU(M) (ice) | xeo | xelu | hielo |

| FILICTU(M) (fern) | fieito | felechu | helecho |

| -ll- | |||

| CASTĔLLU(M) (castle) | castelo | castiellu castieḷḷu |

castillo |

| -N- intervocalic | |||

| RĀNA(M) (frog) | ra | rana | rana |

| Group -LY- | |||

| MULĬERE(M) (woman) | muller | muyer | mujer |

| Groups -C'L-, -T'L-, -G'L- | |||

| NOVACŬLA(M) (penknife) | navalla | navaya | navaja |

| VETŬLU(M) (old) | vello | vieyu | viejo |

| TEGŬLA(M) (tile) | tella | teya | teja |

Lexical comparison

Lord's Prayer

| Asturian | Galician | Latin |

|---|---|---|

|

Pá nuesu que tas nel cielu, santificáu seya'l to nome. Amiye'l to reinu, fágase la to voluntá, lo mesmo na tierra que'n cielu. El nuesu pan cotidianu dánoslu güei ya perdónanos les nueses ofenses, lo mesmo que nós facemos colos que nos faltaron. Nun nos dexes cayer na tentación, ya llíbranos del mal. Amén. |

Noso Pai que estás no ceo: santificado sexa o teu nome, veña a nós o teu reino e fágase a túa vontade aquí na terra coma no ceo. O noso pan cotián dánolo hoxe; e perdóanos as nosas ofensas como tamén perdoamos nós a quen nos ten ofendido; e non nos deixes caer na tentación, mais líbranos do mal. Amén. |

Pater noster, qui es in caelis, Sanctificetur nomen tuum. Adveniat regnum tuum. Fiat voluntas tua, Sicut in caelo et in terra. Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie. Et dimitte nobis debita nostra, Sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris. Et ne nos inducas in tentationem: Sed libera nos a malo. Amen |

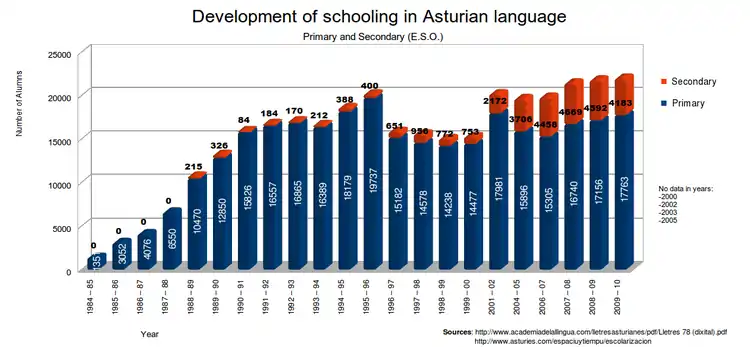

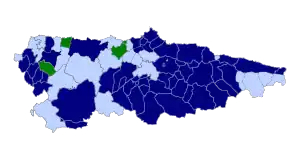

Education

Primary and secondary

Although Spanish is the official language of all schools in Asturias, in many schools children are allowed to take Asturian-language classes from age 6 to 16. Elective classes are also offered from 16 to 19. Central Asturias (Nalón and Caudal comarcas) has the largest percentage of Asturian-language students, with almost 80 percent of primary-school students and 30 percent of secondary-school students in Asturian classes.[37] Xixón, Uviéu, Eo-Navia and Oriente also have an increased number of students.

University

According to article six of the University of Oviedo charter, "The Asturian language will be the object of study, teaching and research in the corresponding fields. Likewise, its use will have the treatment established by the Statute of Autonomy and complementary legislation, guaranteeing non-discrimination of those who use it."[40]

Asturian can be used at the university in accordance with the Use of Asturian Act. University records indicate an increased number of courses and amount of scientific work using Asturian, with courses in the Department of Philology and Educational Sciences.[41] In accordance with the Bologna Process, Asturian philology will be available for study and teachers will be able to specialise in the Asturian language at the University of Oviedo.

Internet

Asturian government websites,[42] council webpages, blogs,[43] and entertainment webpages exist. Free software is offered in Asturian, and Ubuntu offers Asturian as an operating-system language.[44][45] Free software in the language is available from Debian, Fedora, Firefox, Thunderbird, LibreOffice, VLC, GNOME, Chromium and KDE. Minecraft also has an Asturian translation.

Wikipedia offers an Asturian version of itself, with 100,000+ pages as of December 2018.

See also

- Leonese language

- Mirandese language

- List of Asturian language authors

- Extremaduran language

- Ramón Menéndez Pidal

- Category:Asturian-language software in the Asturian Wikipedia

References

- González-Quevedo, Roberto (2001). "The Asturian Speech Community". In Turell, Maria Teresa (ed.). Multilingualism in Spain: Sociolinguistic and Psycholinguistic Aspects of Linguistic Minority Groups. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. pp. 165–182. doi:10.21832/9781853597107-009. ISBN 1-85359-491-1.

- Academia de la Llingua Asturiana (2017). III Encuesta Sociolingüística de Asturias: Avance de Resultados (in Spanish). Oviedo. ISBN 978-84-8168-554-1.

- "Asturian in Asturias in Spain". Database for the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Public Foundation for European Comparative Minority Research. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- Art. 1 de la Ley 1/1998, de 23 de marzo, de uso y promoción del bable/asturiano [Law 1/93, of March 23, on the Use and Promotion of the Asturian Language] (in Spanish)

- Salminen, Tapani (2007). "Europe and North Asia". In Moseley, Christopher (ed.). Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 211–281. doi:10.4324/9780203645659. ISBN 978-0-7007-1197-0.

- "Asturian". ethnologue.com. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "La jueza a Fernando González: "No puede usted hablar en la lengua que le dé la gana"". El Comercio (in Spanish). EFE. 12 January 2009. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- see: Institut de Sociolingüística Catalana (29 May 1998). "Asturian in Spain". Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- Wells, Naomi (2019). "State Recognition for 'Contested Languages': A Comparative Study of Sardinian and Asturian, 1992–2010". Language Policy. 18 (2): 243–267. doi:10.1007/s10993-018-9482-6. S2CID 149849322.

- "Portugal and Spain". Ethnologue. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- Amaya Valencia, E. (1948). "Review of Rafael Lapesa, Asturiano y provenzal en el Fuero de Aviles (Acta Salmanticensia Iussu Senatus Universitatis Edita. Filosofía y Letras. Tomo II, núm. 4). Madrid, C. Bermejo, 1948, 105 págs" (PDF). Thesaurus (in Spanish). 4 (3): 601–602.

- Álvarez, Román Antonio (26 December 2009). "El Fuero de Avilés, recuperado" [The Fuero of Avilés, recovered]. El Comercio (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- Bauske 1995.

- "Lengua asturiana" [Asturian language]. Promotora Española de Lingüística (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Llera Ramo 1994.

- http://www.unioviedo.es/reunido/index.php/RFA/article/download/9260/9111

- Llera-Ramo, F. (1994). Los asturianos y la lengua asturiana: Estudio sociolingüístico para Asturias [Asturians and the Asturian language: Sociolinguistic study for Asturias] (in Spanish). Uviéu: Conseyería d’Educación and Cultura del Principáu d’Asturies.

- Hofkamp, Daniel (22 April 2021). "First Complete Bible in Asturian Language Published". Evangelical Focus Europe. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- Institut de Sociolingüística Catalana (29 May 1998). "Asturian in Spain". uoc.edu. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- García Gil, Héctor, Asturian-Leonese: Linguistic, Sociolinguistic and Legal Aspects (PDF), Working Paper 25, Mercator Legislation, p. 16, ISSN 2013-102X, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2014, retrieved 10 September 2013

- Fuero de Avilés (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2020 – via grufia.com.

- Madroñal, Abraham (2002). "Los Refranes o Proverbios en Romance (1555), de Hernán Núñez, Pinciano". Revista de literatura. 64 (127): 16. doi:10.3989/revliteratura.2002.v64.i127.188. This document has got a unique reference, supposedly in Asturian: "Quien passa por Ruycande y no bebe, o muere de hambre, o no ha sede" Who passes through Ruycande Village and do not drink, or starves or don not have thirst", Hernán Nunez, Refranes o Proverbios en romance que coligio y gloso el comenadador Hernán Nunez, professor de retorica y griego en la Universidad de Salamanca, Lerida, año 1621, p. 81.

- About the character of this literature the Swedish philologist Åke W:son Munthe on 1868 notes the following: "it seems to subsist in this literature an arbitrary mixture of Castilian language elements. This literary production -after a long century of copy and paste and finally because of the editor's final review- seems to be shown in nowadays in a very confusing way. For that reason, we must appoint to Reguera as the author of this literature, that I could call 'bable'. All the later authors, at least from a linguistic point of view, all of them come from his literature archaizing. Naturally, some of these authors take elements of their respective local dialects, and often, also, with others languages, that in some way or another, could have got in contact, as well as of a Spanish language mixture, affected by the 'bable' or not. This literature in 'bable' cannot be considered as a literary language, because have not got any unified body, at least from a linguistic point of view... what in any case, as in whatever other dialects, seems doomed to extinction". Ake W:son Munthe, Anotaciones sobre el habla popular del occidente de AsturiasUpsala 1887, reedition, Publisher Service of the Oviedo University, 1987, p. 3.

- Rodríguez Valdés, Rafael. Llibros 2011: Catálogu de publicaciones (in Asturian). Gobiernu del Principáu d’Asturies. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017.

- Decreto 98/2002, de 18 de julio, por el que se establece el procedimiento de recuperación y fijación de la toponimia asturiana (PDF) (in Spanish) – via Boletin Oficial del Principado de Asturias.

- "Xunta Asesora de Toponimia". Política Llingüística (in Asturian). Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Viejo Fernández, Xulio (1998). "Algunos apuntes pragmáticos sobre el continuo asturiano". Archivum (in Spanish). 48–49: 541–572.

- Penny 2000, pp. 88–89.

- "UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". UNESCO.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2013., where Cantabrian is listed in the Astur-Leonese linguistic group.

- Muñiz-Cachón, Carmen (2018). "Asturian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 48 (2): 231–241. doi:10.1017/S0025100317000202. S2CID 232350125.

- Academia de la Llingua Asturiana (2012) [First edition 1981]. Normes ortográfiques (PDF) (in Asturian) (7th revised ed.). Uviéu: Academia de la Llingua Asturiana. ISBN 978-84-8168-532-9.

- Academia de la Llingua Asturiana (2001). Gramática de la Llingua Asturiana (PDF) (in Asturian) (3rd ed.). Uviéu: Academia de la Llingua Asturiana. ISBN 84-8168-310-8.

- see https://eslema.it.uniovi.es/comun/traductor.php

- Segura Munguía, Santiago (2001). Nuevo diccionario etimológico latín-español y de las voces derivadas (in Spanish). Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto. ISBN 978-84-7485-754-2.

- Seminario de Lexicografía (1990). Diccionario da lingua galega (in Spanish). A Coruña: Real Academia Gallega. ISBN 978-84-600-7509-7.

- Academia de la Llingua Asturiana (2000). Diccionariu de la llingua asturiana (in Asturian). Uvieu: Academia de la Lengua Asturiana. ISBN 978-84-8168-208-3.

- Fernandez, Georgina (1 April 2006). "Las cuencas lideran la escolarización de estudiantes de llingua asturiana". La Voz de Asturias (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Escolarización". Espaciu y Tiempu de la llingua asturiana (in Asturian). Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- Huguet Canalis, Ángel; González Riaño, Xosé Antón (2001). "Actitúes sociollingüístiques del alumnáu de secundaria n'Asturies" (PDF). Lletres Asturianes: Boletín de l'Academia de la Llingua Asturiana (in Asturian) (78): 7–27.

- Statutes of the University of Oviedo, Article 6, published in Decree 12/2010 of the Principality of Asturias (in Spanish) – via BOE.es.

La lengua asturiana será objeto de estudio, enseñanza e investigación en los ámbitos que correspondan. Asimismo, su uso tendrá el tratamiento que establezcan el Estatuto de Autonomía y la legislación complementaria, garantizándose la no discriminación de quien la emplee.

- "Información de la asignatura". directo.uniovi.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

Conocimiento global de la realidad la lengua asturiana, de su unidad e independencia al margen de los fenómenos de variación interna y de su integración en el marco hispano-románico, a partir de un enfoque esencialmente histórico y diacrónico.

- see "Inicio". Gobiernu del Principáu d'Asturies (in Asturian). Archived from the original on June 23, 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- "Blog Channel in Asturian language". Asturies.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Bacon, Jono (30 September 2009). "Ubuntu In Your Language". jonobacon.org. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Stats of Translations in Ubuntu 12.10". canonical.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

Bibliography

- Bauske, Bernd (1995). Sprachplanung des Asturianischen : die Normierung und Normalisierung einer romanischen Kleinsprache im Spannungsfeld von Linguistik, Literatur und Politik (in German). Berlin: Dr. Köster. ISBN 978-3895740572.

- Llera Ramo, Francisco (1994). Los asturianos y la lengua asturiana : estudio sociolingüístico para Asturias, 1991 (in Spanish). Uviéu [Spain]: Principau dʼAsturies, Conseyería dʼEducación, Cultura, Deportes y Xuventu. ISBN 84-7847-297-5.

- Penny, Ralph J. (2000). Variation and change in Spanish. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139164566. ISBN 0521780454. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Wurm, Stephen A. (ed) (2001) Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger of Disappearing. Unesco ISBN 92-3-103798-6.

- (in English) M.Teresa Turell (2001). Multilingualism in Spain: Sociolinguistic and Psycholinguistic Aspects of Linguistic Minority Groups. ISBN 1-85359-491-1

- (in English) Mercator-Education (2002): European Network for Regional or Minority Languages and Education. "The Asturian language in education in Spain" ISSN 1570-1239

External links

- Academia de la Llingua Asturiana – the official Asturian language academy

- Dirección Xeneral de Política Llingüística del Gobiernu del Principáu d'Asturies – Bureau of Asturian Linguistic Policy (Government of the Principality of Asturias)

- Asturian grammar in English Archived 11 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Asturian–English dictionary

- Xunta pola Defensa de la Llingua Asturiana

- Real Instituto de Estudios Asturianos – Royal Institute of Asturian Studies (RIDEA or IDEA), founded 1945.

- A short Asturian–English–Japanese phrasebook Archived 7 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine incl. sound file

- Aconceyamientu de Xuristes pol Asturianu The Advisory Council of Lawyers for Asturian

- II Estudiu Sociollingüísticu d'Asturies (2002)

- Diccionariu de la Academia de la Llingua Asturiana / Dictionary of the Royal Academy of the Asturian Language

- Diccionario General de la lengua asturiana (Asturian — Spanish)

- Eslema, Asturian online translator

- «Asturiano» en PROEL

- Dirección Xeneral de Política Llingüística del Gobiernu del Principáu d'Asturies.

- Proyecto Eslema, "Eslema" Project for the creation of corpus Asturian language domain

- Conferencia sobre socioligüística asturiana impartida por el profesor de la Universidad de Oviedo Ramón d'Andrés en el Instituto Cervantes (Madrid. 2010)