Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics,[3] along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the federal government since being elected in the 2022 election. The ALP is a federal party, with political branches in each state and territory. They are currently in government in Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory, and the Northern Territory. They are currently in opposition in New South Wales and Tasmania. It is the oldest political party in Australia, being established on 8 May 1901 at Parliament House, Melbourne, the meeting place of the first federal Parliament.

Australian Labor Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | ALP |

| Leader | Anthony Albanese |

| Deputy Leader | Richard Marles |

| Senate Leader | Penny Wong |

| President | Wayne Swan[1] |

| National Secretary | Paul Erickson |

| Founded | Oldest branches: 1891 Federal Caucus: 8 May 1901 |

| Headquarters | Barton, Australian Capital Territory |

| Think tank | Chifley Research Centre |

| Youth wing | Australian Young Labor |

| LGBT wing | Rainbow Labor |

| Membership (2020) | |

| Ideology | Social democracy |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| International affiliation |

|

| Union affiliate | ACTU |

| Affiliate parties | Country Labor (2000–2021) |

| Colours | Red |

| Slogan | "A Better Future" |

| Governing body | National Executive |

| Parliamentary party | FPLP |

| Party branches |

|

| House of Representatives | 77 / 151 |

| Senate | 26 / 76 |

| State/territory governments | 6 / 8 |

| State/territory lower houses | 258 / 455 |

| State upper houses | 65 / 155 |

| Website | |

| alp | |

| |

The ALP was not founded as a federal party until after the first sitting of the Australian parliament in 1901. It is regarded as descended from labour parties founded in the various Australian colonies by the emerging labour movement in Australia, formally beginning in 1891. Colonial labour parties contested seats from 1891, and federal seats following Federation at the 1901 federal election. The ALP formed the world's first labour party government and the world's first social-democratic government at a national level.[4] At the 1910 federal election, Labor was the first party in Australia to win a majority in either house of the Australian parliament. In every election since 1910 Labor has either served as the governing party or the opposition. There have been 13 Labor Prime Ministers and 10 Periods of Federal Labor Governments.

At the federal and state/colony level, the Australian Labor Party predates both the British Labour Party and the New Zealand Labour Party in party formation, government, and policy implementation.[5] Internationally, the ALP is a member of the Progressive Alliance, a network of social-democratic parties,[6] having previously been a member of the Socialist International.

Name and spelling

In standard Australian English, the word "labour" is spelt with a u. However, the political party uses the spelling "Labor", without a u. There was originally no standardised spelling of the party's name, with "Labor" and "Labour" both in common usage. According to Ross McMullin, who wrote an official history of the Labor Party, the title page of the proceedings of the Federal Conference used the spelling "Labor" in 1902, "Labour" in 1905 and 1908, and then "Labor" from 1912 onwards.[7] In 1908, James Catts put forward a motion at the Federal Conference that "the name of the party be the Australian Labour Party", which was carried by 22 votes to two. A separate motion recommending state branches adopt the name was defeated. There was no uniformity of party names until 1918 when the Federal party resolved that state branches should adopt the name "Australian Labor Party", now spelt without a u. Each state branch had previously used a different name, due to their different origins.[8][lower-alpha 1]

Although the ALP officially adopted the spelling without a u, it took decades for the official spelling to achieve widespread acceptance.[11][lower-alpha 2] According to McMullin, "the way the spelling of 'Labor Party' was consolidated had more to do with the chap who ended up being in charge of printing the federal conference report than any other reason".[15] Some sources have attributed the official choice of "Labor" to influence from King O'Malley, who was born in the United States and was reputedly an advocate of spelling reform; the spelling without a u is the standard form in American English.[16][17] It has been suggested that the adoption of the spelling without a u "signified one of the ALP's earliest attempts at modernisation", and served the purpose of differentiating the party from the Australian labour movement as a whole and distinguishing it from other British Empire labour parties. The decision to include the word "Australian" in the party's name, rather than just "Labour Party" as in the United Kingdom, has been attributed to "the greater importance of nationalism for the founders of the colonial parties".[18]

History

The Australian Labor Party has its origins in the Labour parties founded in the 1890s in the Australian colonies prior to federation. Labor tradition ascribes the founding of Queensland Labour to a meeting of striking pastoral workers under a ghost gum tree (the "Tree of Knowledge") in Barcaldine, Queensland in 1891. The 1891 shearers' strike is credited as being one of the factors for the formation of the Australian Labor Party. On 9 September 1892 the Manifesto of the Queensland Labour Party was read out under the well known Tree of Knowledge at Barcaldine following the Great Shearers' Strike.[19] The State Library of Queensland now holds the manifesto;[20][21] in 2008 the historic document was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Australian Register[22] and, in 2009, the document was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World International Register.[23] The Balmain, New South Wales branch of the party claims to be the oldest in Australia. However, the Scone Branch has a receipt for membership fees for the 'Labour Electoral League' dated April 1891. This predates the Balmain claim. This can be attested in the Centenary of the ALP book. Labour as a parliamentary party dates from 1891 in New South Wales and South Australia, 1893 in Queensland, and later in the other colonies.

The first election contested by Labour candidates was the 1891 New South Wales election, when Labour candidates (then called the Labor Electoral League of New South Wales) won 35 of 141 seats. The major parties were the Protectionist and Free Trade parties and Labour held the balance of power. It offered parliamentary support in exchange for policy concessions.[24] The United Labor Party (ULP) of South Australia was founded in 1891, and three candidates were that year elected to the South Australian Legislative Council.[25] The first successful South Australian House of Assembly candidate was John McPherson at the 1892 East Adelaide by-election. Richard Hooper however was elected as an Independent Labor candidate at the 1891 Wallaroo by-election, while he was the first "labor" member of the House of Assembly he was not a member of the newly formed ULP.

At the 1893 South Australian elections the ULP was immediately elevated to balance of power status with 10 of 54 lower house seats. The liberal government of Charles Kingston was formed with the support of the ULP, ousting the conservative government of John Downer. So successful, less than a decade later at the 1905 state election, Thomas Price formed the world's first stable Labor government. John Verran led Labor to form the state's first of many majority governments at the 1910 state election.

In 1899, Anderson Dawson formed a minority Labour government in Queensland, the first in the world, which lasted one week while the conservatives regrouped after a split.

The colonial Labour parties and the trade unions were mixed in their support for the Federation of Australia. Some Labour representatives argued against the proposed constitution, claiming that the Senate as proposed was too powerful, similar to the anti-reformist colonial upper houses and the British House of Lords. They feared that federation would further entrench the power of the conservative forces. However, the first Labour leader and Prime Minister Chris Watson was a supporter of federation.

Historian Celia Hamilton, examining New South Wales, argues for the central role of Irish Catholics. Before 1890, they opposed Henry Parkes, the main Liberal leader, and of free trade, seeing them both as the ideals of Protestant Englishmen who represented landholding and large business interests. In the strike of 1890 the leading Catholic, Sydney's Archbishop Patrick Francis Moran was sympathetic toward unions, but Catholic newspapers were negative. After 1900, says Hamilton, Irish Catholics were drawn to the Labour Party because its stress on equality and social welfare fitted with their status as manual labourers and small farmers. In the 1910 elections Labour gained in the more Catholic areas and the representation of Catholics increased in Labour's parliamentary ranks.[26]

Early decades at the federal level

The federal parliament in 1901 was contested by each state Labour Party. In total, they won 14 of the 75 seats in the House of Representatives, collectively holding the balance of power, and the Labour members now met as the Federal Parliamentary Labour Party (informally known as the caucus) on 8 May 1901 at Parliament House, Melbourne, the meeting place of the first federal Parliament.[27] The caucus decided to support the incumbent Protectionist Party in minority government, while the Free Trade Party formed the opposition. It was some years before there was any significant structure or organisation at a national level. Labour under Chris Watson doubled its vote at the 1903 federal election and continued to hold the balance of power. In April 1904, however, Watson and Alfred Deakin fell out over the issue of extending the scope of industrial relations laws concerning the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill to cover state public servants, the fallout causing Deakin to resign. Free Trade leader George Reid declined to take office, which saw Watson become the first Labour Prime Minister of Australia, and the world's first Labour head of government at a national level (Anderson Dawson had led a short-lived Labour government in Queensland in December 1899), though his was a minority government that lasted only four months. He was aged only 37, and is still the youngest Prime Minister in Australia's history.[28]

George Reid of the Free Trade Party adopted a strategy of trying to reorient the party system along Labour vs. non-Labour lines prior to the 1906 federal election and renamed his Free Trade Party to the Anti-Socialist Party. Reid envisaged a spectrum running from socialist to anti-socialist, with the Protectionist Party in the middle. This attempt struck a chord with politicians who were steeped in the Westminster tradition and regarded a two-party system as very much the norm.[29]

Although Watson further strengthened Labour's position in 1906, he stepped down from the leadership the following year, to be succeeded by Andrew Fisher who formed a minority government lasting seven months from late 1908 to mid 1909. At the 1910 federal election, Fisher led Labor to victory, forming Australia's first elected federal majority government, Australia's first elected Senate majority, the world's first Labour Party majority government at a national level, and after the 1904 Chris Watson minority government the world's second Labour Party government at a national level. It was the first time a Labour Party had controlled any house of a legislature, and the first time the party controlled both houses of a bicameral legislature.[30] The state branches were also successful, except in Victoria, where the strength of Deakinite liberalism inhibited the party's growth. The state branches formed their first majority governments in New South Wales and South Australia in 1910, Western Australia in 1911, Queensland in 1915 and Tasmania in 1925. Such success eluded equivalent social democratic and labour parties in other countries for many years.

Analysis of the early NSW Labor caucus reveals "a band of unhappy amateurs", made up of blue collar workers, a squatter, a doctor, and even a mine owner, indicating that the idea that only the socialist working class formed Labor is untrue. In addition, many members from the working class supported the liberal notion of free trade between the colonies; in the first grouping of state MPs, 17 of the 35 were free-traders.

In the aftermath of World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917, support for socialism grew in trade union ranks, and at the 1921 All-Australian Trades Union Congress a resolution was passed calling for "the socialisation of industry, production, distribution and exchange." The 1922 Labor Party National Conference adopted a similarly worded "socialist objective," which remained official policy for many years. The resolution was immediately qualified, however, by the "Blackburn amendment," which said that "socialisation" was desirable only when was necessary to "eliminate exploitation and other anti-social features."[31] In practice the socialist objective was a dead letter. Only once has a federal Labor government attempted to nationalise any industry (Ben Chifley's bank nationalisation of 1947), and that was held by the High Court to be unconstitutional. The commitment to nationalisation was dropped by Gough Whitlam, and Bob Hawke's government carried out many free market reforms including the floating of the dollar and privatisation of state enterprises such as Qantas airways and the Commonwealth Bank.

The Labor Party is commonly described as a social democratic party, and its constitution stipulates that it is a democratic socialist party.[32] The party was created by, and has always been influenced by, the trade unions, and in practice its policy at any given time has usually been the policy of the broader labour movement. Thus at the first federal election 1901 Labor's platform called for a White Australia policy, a citizen army and compulsory arbitration of industrial disputes.[33] Labor has at various times supported high tariffs and low tariffs, conscription and pacifism, White Australia and multiculturalism, nationalisation and privatisation, isolationism and internationalism.

Historically, Labor and its affiliated unions were strong defenders of the White Australia policy, which banned all non-European migration to Australia. This policy was partly motivated by 19th century theories about "racial purity" and by fears of economic competition from low-wage overseas workers which was shared by the vast majority of Australians and all major political parties. In practice the Labor party opposed all migration, on the grounds that immigrants competed with Australian workers and drove down wages, until after World War II, when the Chifley Government launched a major immigration program. The party's opposition to non-European immigration did not change until after the retirement of Arthur Calwell as leader in 1967. Subsequently, Labor has become an advocate of multiculturalism, although some of its trade union base and some of its members continue to oppose high immigration levels.

World War II and beyond

The Curtin and Chifley governments governed Australia through the latter half of the Second World War and initial stages of transition to peace. Labor leader John Curtin became prime minister in October 1941 when two independents crossed the floor of Parliament. Labor, led by Curtin, then led Australia through the years of the Pacific War. In December 1941, Curtin announced that "Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom", thus helping to establish the Australian-American alliance (later formalised as ANZUS by the Menzies Government). Remembered as a strong war time leader and for a landslide win at the 1943 federal election, Curtin died in office just prior to the end of the war and was succeeded by Ben Chifley.[34] Chifley Labor won the 1946 federal election and oversaw Australia's initial transition to a peacetime economy.

Labor was defeated at the 1949 federal election. At the conference of the New South Wales Labor Party in June 1949, Chifley sought to define the labour movement as follows: "We have a great objective – the light on the hill – which we aim to reach by working for the betterment of mankind. [...] [Labor would] bring something better to the people, better standards of living, greater happiness to the mass of the people."[35]

To a large extent, Chifley saw centralisation of the economy as the means to achieve such ambitions. With an increasingly uncertain economic outlook, after his attempt to nationalise the banks and a strike by the Communist-dominated Miners' Federation, Chifley lost office in 1949 to Robert Menzies' Liberal-National Coalition. Labor commenced a 23-year period in opposition.[36][37] The party was primarily led during this time by H. V. Evatt and Arthur Calwell.

.jpg.webp)

Various ideological beliefs were factionalised under reforms to the ALP under Gough Whitlam, resulting in what is now known as the Socialist Left who tend to favour a more interventionist economic policy and more socially progressive ideals, and Labor Right, the now dominant faction that tends to be more economically liberal and focus to a lesser extent on social issues. The Whitlam Labor government, marking a break with Labor's socialist tradition, pursued social-democratic policies rather than democratic socialist policies. In contrast to earlier Labor leaders, Whitlam also cut tariffs by 25 percent.[38] Whitlam led the Federal Labor Party back to office at the 1972 and 1974 federal elections, and passed a large amount of legislation. The Whitlam Government lost office following the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis and dismissal by Governor-General John Kerr after the Coalition blocked supply in the Senate after a series of political scandals, and was defeated at the 1975 federal election in the largest landslide of Australian federal history.[39] Whitlam remains the only Prime Minister to have his commission terminated in that manner. Whitlam also lost the 1977 federal election and subsequently resigned as leader.

Bill Hayden succeeded Whitlam as leader. At the 1980 federal election, the party achieved a big swing, though the unevenness of the swing around the nation prevented an ALP victory. In 1983, Bob Hawke became leader of the party after Hayden resigned to avoid a leadership spill.

Bob Hawke led Labor back to office at the 1983 federal election and the party won four consecutive elections under Hawke. In December 1991 Paul Keating defeated Bob Hawke in a leadership spill. The ALP then won the 1993 federal election. It was in power for five terms over 13 years, until severely defeated by John Howard at the 1996 federal election. This was the longest period the party has ever been in government at the national level.

Kim Beazley led the party to the 1998 federal election, winning 51 percent of the two-party-preferred vote but falling short on seats, and the ALP lost ground at the 2001 federal election. After a brief period when Simon Crean served as ALP leader, Mark Latham led Labor to the 2004 federal election but lost further ground. Beazley replaced Latham in 2005; not long afterwards he in turn was forced out of the leadership by Kevin Rudd.

Rudd went on to defeat John Howard at the 2007 federal election with 52.7 percent of the two-party vote (Howard became the first Prime Minister since Stanley Melbourne Bruce to lose not just the election but his own parliamentary seat). The Rudd Government ended prior to the 2010 federal election with the overthrow of Rudd as leader of the Party by deputy leader Julia Gillard. Gillard, who was also the first woman to serve as Prime Minister of Australia,[40] remained Prime Minister in a hung parliament following the election. Her government lasted until 2013, when Gillard lost a leadership spill, with Rudd becoming leader once again. Later that year the ALP lost the 2013 election.

After this defeat, Bill Shorten became leader of the party. The party narrowly lost the 2016 election, yet gained 14 seats. It remained in opposition after the 2019 election, despite having been ahead in opinion polls for the preceding two years. The party lost in 2019 some of the seats which it had won back in 2016. After the 2019 defeat, Shorten resigned from the leadership, though he remained in parliament. Anthony Albanese was elected as leader unopposed and led the party to victory in the 2022 election.

Between the 2007 federal election and the 2008 Western Australian state election, Labor was in government nationally and in all eight state and territory legislatures. This was the first time any single party or any coalition had achieved this since the ACT and the NT gained self-government.[44] Labor narrowly lost government in Western Australia at the 2008 state election and Victoria at the 2010 state election. These losses were further compounded by landslide defeats in New South Wales in 2011, Queensland in 2012, the Northern Territory in 2012, Federally in 2013 and Tasmania in 2014.[45] Labor secured a good result in the Australian Capital Territory in 2012 and, despite losing its majority, the party retained government in South Australia in 2014.[46]

However, most of these reversals proved only temporary with Labor returning to government in Victoria in 2014 and in Queensland in 2015 after spending only one term in opposition in both states.[47] Furthermore, after winning the 2014 Fisher by-election by nine votes from a 7.3 percent swing, the Labor government in South Australia went from minority to majority government.[48] Labor won landslide victories in the 2016 Northern Territory election, the 2017 Western Australian election and the 2018 Victorian state election. However, Labor lost the 2018 South Australian state election after 16 years in government. In 2022, Labor returned to government after defeating the Liberal Party in the 2022 South Australian state election. Despite favourable polling, the party also did not return to government in the 2019 New South Wales state election or the 2019 federal election. The latter has been considered a historic upset due to Labor's consistent and significant polling lead; the result has been likened to the Coalition's loss in the 1993 federal election, with 2019 retrospectively referred to as "unloseable election".[49][50] Anthony Albanese later led the party into the 2022 Australian federal election, in which the party once again won a majority government.

National platform

The policy of the Australian Labor Party is contained in its National Platform, which is approved by delegates to Labor's National Conference, held every three years. According to the Labor Party's website, "The Platform is the result of a rigorous and constructive process of consultation, spanning the nation and including the cooperation and input of state and territory policy committees, local branches, unions, state and territory governments, and individual Party members. The Platform provides the policy foundation from which we can continue to work towards the election of a federal Labor Government."[51]

The platform gives a general indication of the policy direction which a future Labor government would follow, but does not commit the party to specific policies. It maintains that "Labor's traditional values will remain a constant on which all Australians can rely." While making it clear that Labor is fully committed to a market economy, it says that: "Labor believes in a strong role for national government – the one institution all Australians truly own and control through our right to vote." Labor "will not allow the benefits of change to be concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, or located only in privileged communities. The benefits must be shared by all Australians and all our regions." The platform and Labor "believe that all people are created equal in their entitlement to dignity and respect, and should have an equal chance to achieve their potential." For Labor, "government has a critical role in ensuring fairness by: ensuring equal opportunity; removing unjustifiable discrimination; and achieving a more equitable distribution of wealth, income and status." Further sections of the platform stress Labor's support for equality and human rights, labour rights and democracy.

In practice, the platform provides only general policy guidelines to Labor's federal, state and territory parliamentary leaderships. The policy Labor takes into an election campaign is determined by the Cabinet (if the party is in office) or the Shadow Cabinet (if it is in opposition), in consultation with key interest groups within the party, and is contained in the parliamentary Leader's policy speech delivered during the election campaign. When Labor is in office, the policies it implements are determined by the Cabinet, subject to the platform. Generally, it is accepted that while the platform binds Labor governments, how and when it is implemented remains the prerogative of the parliamentary caucus. It is now rare for the platform to conflict with government policy, as the content of the platform is usually developed in close collaboration with the party's parliamentary leadership as well as the factions. However, where there is a direct contradiction with the platform, Labor governments have sought to change the platform as a prerequisite for a change in policy. For example, privatisation legislation under the Hawke government occurred only after holding a special national conference to debate changing the platform.

Party structure

| Part of a series on |

| Organised labour |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Labour politics in Australia |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

|

National executive and secretariat

The Australian Labor Party National Executive is the party's chief administrative authority, subject only to Labor's national conference. The executive is responsible for organising the triennial national conference; carrying out the decisions of the conference; interpreting the national constitution, the national platform and decisions of the national conference; and directing federal members.[52]

The party holds a national conference every three years, which consists of delegates representing the state and territory branches (many coming from affiliated trade unions, although there is no formal requirement for unions to be represented at the national conference). The national conference decides the party's platform, elects the national executive and appoints office-bearers such as the national secretary, who also serves as national campaign director during elections. The current national secretary is Paul Erickson. The most recent national conference was the 48th conference held in December 2018.[53]

The head office of the ALP, the national secretariat, is managed by the national secretary. It plays a dual role of administration and a national campaign strategy. It acts as a permanent secretariat to the national executive by managing and assisting in all administrative affairs of the party. As the national secretary also serves as national campaign director during elections, it is also responsible for the national campaign strategy and organisation.

Federal Parliamentary Labor Party

The elected members of the Labor party in both houses of the national Parliament meet as the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, also known as the Australian Labor Party Caucus (see also caucus).[54] Besides discussing parliamentary business and tactics, the Caucus also is involved in the election of the federal parliamentary leaders.

Federal parliamentary leaders

Until 2013, the parliamentary leaders were elected by the Caucus from among its members. The leader has historically been a member of the House of Representatives. Since October 2013, a ballot of both the Caucus and by the Labor Party's rank-and-file members determined the party leader and the deputy leader.[55] When the Labor Party is in government, the party leader is the Prime Minister and the deputy leader is the Deputy Prime Minister. If a Labor prime minister resigns or dies in office, the deputy leader acts as prime minister and party leader until a successor is elected. The deputy prime minister also acts as prime minister when the prime minister is on leave or out of the country. Members of the Ministry are also chosen by Caucus, though the leader may allocate portfolios to the ministers.

Anthony Albanese is the leader of the federal Labor party, serving since 30 May 2019. The deputy leader is Richard Marles, also serving since 30 May 2019.

State and territory branches

The Australian Labor Party is a federal party, consisting of eight branches from each state and territory. While the National Executive is responsible for national campaign strategy, each state and territory are an autonomous branch and are responsible for campaigning in their own jurisdictions for federal, state and local elections. State and territory branches consist of both individual members and affiliated trade unions, who between them decide the party's policies, elect its governing bodies and choose its candidates for public office.

Members join a state branch and pay a membership fee, which is graduated according to income. The majority of trade unions in Australia are affiliated to the party at a state level. Union affiliation is direct and not through the Australian Council of Trade Unions. Affiliated unions pay an affiliation fee based on the size of their membership. Union affiliation fees make up a large part of the party's income. Other sources of funds for the party include political donations and public funding.

Members are generally expected to attend at least one meeting of their local branch each year, although there are differences in the rules from state to state. In practice only a dedicated minority regularly attend meetings. Many members are only active during election campaigns.

The members and unions elect delegates to state and territory conferences (usually held annually, although more frequent conferences are often held). These conferences decide policy, and elect state or territory executives, a state or territory president (an honorary position usually held for a one-year term), and a state or territory secretary (a full-time professional position). However, ACT Labor directly elects its president. The larger branches also have full-time assistant secretaries and organisers. In the past the ratio of conference delegates coming from the branches and affiliated unions has varied from state to state, however under recent national reforms at least 50% of delegates at all state and territory conferences must be elected by branches.

In some states it also contests local government elections or endorses local candidates. In others it does not, preferring to allow its members to run as non-endorsed candidates. The process of choosing candidates is called preselection. Candidates are preselected by different methods in the various states and territories. In some they are chosen by ballots of all party members, in others by panels or committees elected by the state conference, in still others by a combination of these two.

The state and territory Labor branches are the following:

| Branch | Leader | Last election | Status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower House | Upper House | ||||||||

| Year | Votes (%) | Seats | TPP (%) | Votes (%) | Seats | ||||

| NSW Labor | Chris Minns | 2019 | 33.3 | 36 / 93 |

48.0 | 29.7 | 14 / 42 |

Opposition | |

| Victorian Labor | Daniel Andrews | 2018 | 42.9 | 55 / 88 |

57.3 | 39.2 | 18 / 40 |

Majority government | |

| Queensland Labor | Annastacia Palaszczuk | 2020 | 39.5 | 52 / 93 |

53.2 | N/A [lower-alpha 3] | Majority government | ||

| WA Labor | Mark McGowan | 2021 | 59.1 | 53 / 59 |

69.2 | 60.3 | 22 / 36 |

Majority government | |

| South Australian Labor | Peter Malinauskas | 2022 | 40.0 | 27 / 47 |

54.6 | 37.0 | 9 / 22 |

Majority government | |

| Tasmanian Labor | Rebecca White | 2021 | 28.2 | 9 / 25 |

N/A [lower-alpha 4] | N/A[lower-alpha 5] | 4 / 15 |

Opposition | |

| ACT Labor | Andrew Barr | 2020 | 37.8 | 10 / 25 |

N/A [lower-alpha 6] | N/A [lower-alpha 7] | Coalition government with ACT Greens | ||

| NT Labor | Natasha Fyles | 2020 | 42.2 | 14 / 25 |

53.3 | N/A [lower-alpha 8] | Majority government | ||

Country Labor

The Country Labor party was an Australian political party affiliated and/or a division of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). Although not expressly defined, Country Labor operates mainly within rural New South Wales, and is mainly seen as an extension of the New South Wales branch that operates in rural electorates.

Country Labor is a subsection of the ALP, and is used as a designation by candidates contesting elections in rural areas. The Country Labor Party is registered as a separate party in New South Wales,[56] and is also registered with the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) for federal elections.[57] It does not have the same status in other states and, consequently, that designation cannot be used on the ballot paper.

The creation of a separation designation for rural candidates was first suggested at the June 1999 ALP state conference in New South Wales. In May 2000, following Labor's success at the 2000 Benalla by-election in Victoria, Kim Beazley announced that the ALP intended to register a separate "Country Labor Party" with the AEC;[58] this occurred in October 2000.[57] The Country Labor designation is most frequently used in New South Wales. According to the ALP's financial statements for the 2015–16 financial year, NSW Country Labor had around 2,600 members (around 17 percent of the party total), but almost no assets. It recorded a severe funding shortfall at the 2015 New South Wales election, and had to rely on a $1.68-million loan from the party proper to remain solvent. It had been initially assumed that the party proper could provide the money from its own resources, but the NSW Electoral Commission ruled that this was impermissible because the parties were registered separately. Instead the party proper had to loan Country Labor the required funds at a commercial interest rate.[59]

The Country Labor Party was de-registered by the New South Wales Electoral Commission in 2021.[60]

Australian Young Labor

Australian Young Labor is the youth wing of the Australian Labor Party, where all members under age 26 are automatically members. It is the peak youth body within the ALP. Former presidents of AYL have included former NSW Premier Bob Carr, Federal Manager of Opposition Business Tony Burke, former Special Minister of State Senator John Faulkner, former Australian Workers Union National Secretary, current Member for Maribyrnong and former Federal Labor Leader Bill Shorten as well as dozens of State Ministers and MPs. The current National President is Jason Byrne from South Australia.

Networks

The Australian Labor Party is beginning to formally recognise single interest groups within the party. The national platform currently encourages state branches to formally establish these groups known as policy action caucuses.[61] Examples of such groups include the Labor Environment Action Network,[62] Rainbow Labor,[63] Labor For Choice, Labor Women's Network,[64] Labor for Drug Law Reform[65] Labor for Refugees,[66] Labor for Housing,[67] Labor Teachers Network,[68] Aboriginal Labor Network,[69] and recently, Labor Enabled - the action group for Disability Advocacy[70] The Tasmanian Branch of the Australian Labor Party recently gave these groups voting and speaking rights at their state conference.

Ideology and factions

Labor's constitution has long stated: "The Australian Labor Party is a democratic socialist party and has the objective of the democratic socialisation of industry, production, distribution and exchange, to the extent necessary to eliminate exploitation and other anti-social features in these fields".[71] This "socialist objective" was introduced in 1921, but was later qualified by two further objectives: "maintenance of and support for a competitive non-monopolistic private sector" and "the right to own private property". Labor governments have not attempted the "democratic socialisation" of any industry since the 1940s, when the Chifley Government failed to nationalise the private banks, and in fact have privatised several industries such as aviation and banking.[72][73][74][75] Labor's current National Platform describes the party as "a modern social democratic party".[71] Observers have also described it as social-democratic[76][77][78] in contrast to democratic socialism.

Factions

Parliamentary caucus seats | |

|---|---|

| Labor Right | 42 / 103 |

| Labor Left | 43 / 103 |

The Labor Party has always had a left wing and a right wing, but since the 1970s it has been organised into formal factions, to which party members may belong and often pay an additional membership fee. The two largest factions are the Labor Left and the Labor Right, led by Anthony Albanese and Bill Shorten, respectively. The Labor Right generally supports free-market policies and the US alliance and tends to be conservative on some social issues, whilst the Labor Left favours more state intervention in the economy, is generally less enthusiastic about the US alliance and is often more progressive on social issues. The national factions are themselves divided into sub-factions, primarily state-based such as Centre Unity in New South Wales and Labor Forum in Queensland. Those factions tend to occupy social-liberal,[79] and social democratic positions.[80]

Some trade unions are affiliated with the Labor Party and are also factionally aligned. The largest unions supporting the right faction are the Australian Workers' Union (AWU), the Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees' Association (SDA) and the Transport Workers Union (TWU).[81] Important unions supporting the left include the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union (AMWU), United Workers Union, the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (CFMMEU) and the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU).[81]

Preselections are usually conducted along factional lines, although sometimes a non-factional candidate will be given preferential treatment (this happened with Cheryl Kernot in 1998 and again with Peter Garrett in 2004). Deals between the factions to divide up the safe seats between them often take place. Preselections, particularly for safe Labor seats, can sometimes be strongly contested. A particularly fierce preselection sometimes gives rise to accusations of branch stacking (signing up large numbers of nominal party members to vote in preselection ballots), personation, multiple voting and, on occasions, fraudulent electoral enrolment. Trade unions were in the past accused of giving inflated membership figures to increase their influence over preselections, but party rules changes have stamped out this practice. Preselection results are sometimes challenged, and the National Executive is sometimes called on to arbitrate these disputes.

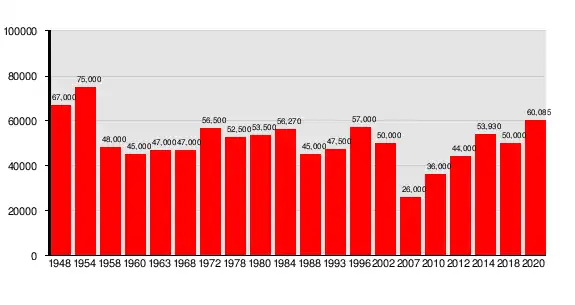

Federal election results

House of Representatives

| Election | Leader | Votes | % | Seats | ± | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | Chris Watson | 79,736 | 15.76 | 14 / 75 |

External support | |

| 1903 | 223,163 | 30.95 | 22 / 75 |

Support (1903–04) | ||

| Minority government (1904) | ||||||

| Opposition (1904–05) | ||||||

| Support (1905–06) | ||||||

| 1906 | 348,711 | 36.64 | 26 / 75 |

Support (1906–08) | ||

| Minority government (1908–09) | ||||||

| Opposition (1909–10) | ||||||

| 1910 | Andrew Fisher | 660,864 | 49.97 | 42 / 75 |

Majority government | |

| 1913 | 921,099 | 48.47 | 37 / 75 |

Opposition | ||

| 1914 | 858,451 | 50.89 | 42 / 75 |

Majority government | ||

| 1917 | Frank Tudor | 827,541 | 43.94 | 22 / 75 |

Opposition | |

| 1919 | 811,244 | 42.49 | 26 / 75 |

Opposition | ||

| 1922 | Matthew Charlton | 665,145 | 42.30 | 29 / 75 |

Opposition | |

| 1925 | 1,313,627 | 45.04 | 23 / 75 |

Opposition | ||

| 1928 | James Scullin | 1,158,505 | 44.64 | 31 / 75 |

Opposition | |

| 1929 | 1,406,327 | 48.84 | 46 / 75 |

Majority government | ||

| 1931 | 859,513 | 27.10 | 14 / 75 |

Opposition | ||

| 1934 | 952,251 | 26.81 | 18 / 74 |

Opposition | ||

| 1937 | John Curtin | 1,555,737 | 43.17 | 29 / 74 |

Opposition | |

| 1940 | 1,556,941 | 40.16 | 32 / 74 |

Opposition (1940–41) | ||

| Minority government (1941–43) | ||||||

| 1943 | 2,058,578 | 49.94 | 49 / 74 |

Majority government | ||

| 1946 | Ben Chifley | 2,159,953 | 49.71 | 43 / 75 |

Majority government | |

| 1949 | 2,117,088 | 45.98 | 47 / 121 |

Opposition | ||

| 1951 | 2,174,840 | 47.63 | 52 / 121 |

Opposition | ||

| 1954 | H. V. Evatt | 2,280,098 | 50.03 | 57 / 121 |

Opposition | |

| 1955 | 1,961,829 | 44.63 | 47 / 122 |

Opposition | ||

| 1958 | 2,137,890 | 42.81 | 45 / 122 |

Opposition | ||

| 1961 | Arthur Calwell | 2,512,929 | 47.90 | 60 / 122 |

Opposition | |

| 1963 | 2,489,184 | 45.47 | 50 / 122 |

Opposition | ||

| 1966 | 2,282,834 | 39.98 | 41 / 124 |

Opposition | ||

| 1969 | Gough Whitlam | 2,870,792 | 46.95 | 59 / 125 |

Opposition | |

| 1972 | 3,273,549 | 49.59 | 67 / 125 |

Majority government | ||

| 1974 | 3,644,110 | 49.30 | 66 / 127 |

Majority government (1974–75)[lower-alpha 9] | ||

| Opposition (1975) | ||||||

| 1975 | 3,313,004 | 42.84 | 36 / 127 |

Opposition | ||

| 1977 | 3,141,051 | 39.65 | 38 / 124 |

Opposition | ||

| 1980 | Bill Hayden | 3,749,565 | 45.15 | 51 / 125 |

Opposition | |

| 1983 | Bob Hawke | 4,297,392 | 49.48 | 75 / 125 |

Majority government | |

| 1984 | 4,120,130 | 47.55 | 82 / 148 |

Majority government | ||

| 1987 | 4,222,431 | 45.76 | 86 / 148 |

Majority government | ||

| 1990 | 3,904,138 | 39.44 | 78 / 148 |

Majority government | ||

| 1993 | Paul Keating | 4,751,390 | 44.92 | 80 / 147 |

Majority government | |

| 1996 | 4,217,765 | 38.69 | 49 / 148 |

Opposition | ||

| 1998 | Kim Beazley | 4,454,306 | 40.10 | 67 / 148 |

Opposition | |

| 2001 | 4,341,420 | 37.84 | 65 / 150 |

Opposition | ||

| 2004 | Mark Latham | 4,408,820 | 37.63 | 60 / 150 |

Opposition | |

| 2007 | Kevin Rudd | 5,388,184 | 43.38 | 83 / 150 |

Majority government | |

| 2010 | Julia Gillard | 4,711,363 | 37.99 | 72 / 150 |

Minority government | |

| 2013 | Kevin Rudd | 4,311,365 | 33.38 | 55 / 150 |

Opposition | |

| 2016 | Bill Shorten | 4,702,296 | 34.73 | 69 / 150 |

Opposition | |

| 2019 | 4,752,631 | 33.34 | 68 / 151 |

Opposition | ||

| 2022 | Anthony Albanese | 4,776,030 | 32.58 | 77 / 151 |

Majority government |

Donors

For the 2015–2016 financial year, the top ten disclosed donors to the ALP were the Health Services Union NSW ($389,000), Village Roadshow ($257,000), Electrical Trades Union of Australia ($171,000), National Automotive Leasing and Salary Packaging Association ($153,000), Westfield Corporation ($150,000), Randazzo C&G Developments ($120,000), Macquarie Telecom ($113,000), Woodside Energy ($110,000), ANZ Bank ($100,000) and Ying Zhou ($100,000),[82][83] all significantly lower than the 2014 donations by a Chinese donor Zi Chun Wang, which at $850,000 [84] was the largest donation to any political party in the 2013-2014 financial year.[85] At least one newspaper report queried the identity of this donor stating "news archive searches do not produce results for this name, suggesting Wang operates under another name".[86] Another report mentions that in addition to a hotel and a travel agency, the donor's listed address at the Old Communist Cadres Activity Centre in Shijiazhuang houses several Chinese government entities, stating also that another publisher "tried many times without success" to contact the donor on the phone number listed in the donation return form.[87]

The Labor Party also receives undisclosed funding through several methods, such as "associated entities". John Curtin House, Industry 2020, IR21 and the Happy Wanderers Club are entities which have been used to funnel donations to the Labor Party without disclosing the source.[88][89][90][91]

A 2019 report found that the Labor Party received $33,000 from pro-gun groups during the 2011–2018 periods,[92] however, the Coalition received over $82,000 in donations from pro-gun groups, more than doubling Labor's pro-gun donors.[92]

See also

- Socialism in Australia

- Australian labour movement

- Third Way

Further reading

Ormonde, Paul (1982). A Foolish Passionate Man: a biography of Jim Cairns. Ringwood, Vic, Australia: Penguin Books. ISBN 014005975X.

Ormonde, Paul (1972). The Movement. Sydney: Thomas Nelson. SBN 170019683

Charlesworth, M. J. (2000) Ormonde, Paul (Ed). Santamaria : the politics of fear : critical reflections. Richmond, Vic.: Spectrum Publications. ISBN 0867862947

Notes

- According to The Australian Worker, in 1918 the state parties comprised the Political Labor League (New South Wales), the Queensland Labor Party, the United Labor Party (South Australia), the Workers' Political Labor League (Tasmania), the Political Labor Council (Victoria), and the Australian Labor Federation (Western Australia).[9] However, according to the South Australian Register, the state parties in New South Wales, South Australia, and Victoria had already adopted the standardised name by 1917.[10]

- In 1954, Labor MP Ted Johnson complained in the Parliament of Western Australia that both Hansard and the daily newspapers were still using the spelling "Labour".[12] As late as the 1980s, historian Finlay Crisp used the spelling "Labour" in academic works about the party.[13][14]

- Queensland no longer has an upper house, it voted to dissolve its Legislative Council in 1922

- Tasmania uses a semi-proportional system and thus TPP is not calculated.

- Tasmania elects legislative council representatives on a periodic basis, with elections held almost every year

- The ACT uses a semi-proportional system and thus TPP is not calculated.

- The ACT has a Unicameral parliament

- The NT has a Unicameral parliament

- The Whitlam Government became the Opposition after the Governor-General, John Kerr, dismissed it during the 1975 constitutional crisis, despite Labor maintaining a majority in the House of Representatives.

References

- "National Executive". Australian Labor Party. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- Davies, Anne (13 December 2020). "Party hardly: why Australia's big political parties are struggling to compete with grassroots campaigns". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Australian Labor Party". Britannica. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- Rhodes, Campbell (27 April 1904). "A perfect picture of the statesman: John Christian Watson". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Australian Labor Party". AustralianPolitics.com. 6 October 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- "Participants". Progressive Alliance. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- McMullin 1991, p. ix.

- McMullin 1991, p. 116.

- "'The Australian Labor Party: Labor's Uniform Name". The Australian Worker. 12 December 1918.

- "What's in a Name?". South Australian Register. 15 September 1917.

- Crowley, Frank (2000). Big John Forrest: A Founding Father of the Commonwealth of Australia. UWA Press. p. 394.

The Commonwealth conference of the party adopted the spelling 'Labor' in the official title of the Labor Party, but the parliamentary debates did not follow suit. Thereafter the debates recorded the same proceedings with different spellings, and it was many years before the spelling 'Labor' was accepted officially or used consistently in print.

- "Australian Labour Party, as to spelling of "Labour"" (PDF). Hansard / Parliament of Western Australia. 7 July 1954. p. 302. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Crisp, Finlay (1978) [1951]. The Australian Federal Labour Party, 1901–1951.

- Crisp, Finlay; Atkinson, Barbara (1981). Australian Labour Party Federal Parliamentarians, 1901–1981.

- McMullin, Ross (2006). "First in the World: Australia's Watson Labor Government". Papers on Parliament. Australian Parliamentary Library (44).

- Bastian, Peter (2009). Andrew Fisher: An Underestimated Man. UNSW Press. p. 372.

- "Disemvowelled". BBC News. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Scott, Andrew (2000). Running on Empty: 'Modernising' the British and Australian Labour Parties (PDF). Pluto Press. p. 39.

- "125th anniversary of the Manifesto of the Queensland Labour Party | State Library Of Queensland". www.slq.qld.gov.au. 8 September 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

-

This Wikipedia article incorporates text from Charles Seymour Papers 1880-1924: Treasure collection of the John Oxley Library (8 November 2021) published by the State Library of Queensland under CC-BY licence, accessed on 2 June 2022.

This Wikipedia article incorporates text from Charles Seymour Papers 1880-1924: Treasure collection of the John Oxley Library (8 November 2021) published by the State Library of Queensland under CC-BY licence, accessed on 2 June 2022.

- "OM69-18 Charles Seymour Papers 1880-1924". State Library of Queensland. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- "Manifesto of the Queensland Labour Party, 1892 | Australian Memory of the World". www.amw.org.au. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- "Manifesto of the Queensland Labour Party to the people of Queensland (dated 9 September 1892) | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- McMullen, Ross (2004). So Monstrous a Travesty: Chris Watson and the World's First National Labour Government. Carlton North, Victoria: Scribe Publications. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-920769-13-0.

- Alison Painter. "9 May 1891 United Labor Party elected to Legislative Council (Celebrating South Australia)". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Celia Hamilton, "Irish‐Catholics of New South Wales and the Labor Party, 1890–1910." Historical Studies: Australia & New Zealand (1958) 8#31: 254–267.

- Faulkner & Macintyre 2001, p. 3.

- Nairn, Bede (1990). "Watson, John Christian (Chris) (1867–1941)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 12. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 9 February 2010 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- Charles Richardson (25 January 2009). "Fusion: The Party System We Had To Have?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Murphy, D. J. (1981). Fisher, Andrew (1862–1928). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 8. Canberra: Australian National University. Archived from the original on 19 June 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- McKinlay 1981, p. 53.

- "National Constitution of the ALP". Official Website of the Australian Labor Party. Australian Labor Party. 2009. Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

The Australian Labor Party is a democratic socialist party and has the objective of the democratic socialisation of industry, production, distribution and exchange, to the extent necessary to eliminate exploitation and other anti-social features in these fields.

- McKinlay 1981, p. 19.

- "John Curtin – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- "In office – Ben Chifley – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". National Archives of Australia. 24 February 2009. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- "Ben Chifley – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. 13 June 1951. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- "Elections – Robert Menzies – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- "Tariff Reduction". The Whitlam Collection. The Whitlam Institute. Archived from the original on 20 July 2005.

- "The dismissal: a brief history". The Age. Melbourne. 11 November 2005.

- "About Julia Gillard". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "DATABASE BY COUNTRY |". Members & Activists of Political Parties.

- Davies, Anne (12 December 2020). "Party hardly: why Australia's big political parties are struggling to compete with grassroots campaigns". The Guardian.

- "Mark Butler: factions are destroying Labor's capacity to campaign". The Guardian. 23 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- In 1969–1970, before the ACT and NT achieved self-government, the Liberal and National Coalition was in power federally and in all six states. University of WA elections database

- Crawford, Barclay (27 March 2011). "Barry O'Farrell smashes Labor in NSW election". The Sunday Telegraph.

- "Weatherill pledges more regional focus amid Brock support". the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 24 March 2014.

- Remeikis, Amy (1 February 2015). "Queensland election: State wakes to new political landscape". the Brisbane Times.

- "Fisher by-election: Recount sees Labor's Nat Cook win by nine votes". the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 16 December 2014.

- Murphy, Katharine (19 May 2019). "Labor lost the unlosable election – now it's up to Morrison to tell Australia his plan". The Guardian.

- Norman, Jane (22 September 2019). "Labor was going to hit the ground running – it hit a brick wall instead". ABC News.

- "ALP National Platform and Constitution 2007". Australian Labor Party. Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- "ALP National Platform 2011" (PDF). Australian Labor Party. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ALP: 2018 Australian Labor Party National Conference

- "National Platform of the Australian Labor Party" (PDF). Australian Labor Party. p. 215. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Harrison, Bill (13 October 2013). "Bill Shorten elected Labor leader". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- List of Registered Parties, Electoral Commission NSW.

- Current register of political parties, Australian Electoral Commission.

- Country Labor: a new direction?, 7 June 2000. Retrieved 29 September 2017

- Near-insolvent Country Labor ‘may never repay’ $1.68m to party, The Australian, 28 July 2017.

- "Cancellation of Registration of Political Party" (PDF). New South Wales Electoral Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- "National Platform of the Australian Labor Party" (PDF). Australian Labor Party. p. 232. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- "Labor Environment Action Network". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Rainbow Labor". Archived from the original on 23 September 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- "National Labor Women's Network". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- "Labor for Drug Law Reform - NSW". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- "Labor for Refugees". Facebook. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Labor for Housing". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- "Labor Teachers". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- "NSW Aboriginal Labor Network". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- "NSW Labor Enabled". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- Wright, George (3 December 2011). "National Platform". Australian Labour Party. Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Frankel, Boris (1997). "Beyond Labourism and Socialism: How the Australian Labor Party developed the Model of 'New Labour'" (PDF). New Left Review. 1 (221): 3–33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Lavelle, Ashley (1 December 2005). "Social Democrats and Neo-Liberalism: A Case Study of the Australian Labor Party". Political Studies. 53 (4): 753–771. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00555.x. S2CID 144842245.

- Lavelle, Ashley (May 2010). "The Ties that Unwind? Social Democratic Parties and Unions in Australia and Britain". Labour History. 53 (98): 55–75. doi:10.5263/labourhistory.98.1.55. JSTOR 10.5263/labourhistory.98.1.55. S2CID 152364613.

- Humphrys, Elizabeth (8 October 2018). How Labour Built Neoliberalism: Australia's Accord, the Labour Movement and the Neoliberal Project. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-38346-3.

- Gauja, Anika; Miragliotta, Narelle; Smith, Rodney, eds. (2015). Contemporary Australian Political Party Organisations. Monash University Publishing. ISBN 9781922235824.

- Johnson, Carol (8 August 2018). "The Australian Right in the "Asian Century": Inequality and Implications for Social Democracy". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 48 (4): 622–648. doi:10.1080/00472336.2018.1441894. hdl:2440/113425. ISSN 0047-2336. S2CID 158392608.

- Matteo Bonotti; Paul Strangio (2021). A century of compulsory voting in Australia : genesis, impact and future. Singapore. p. 103. ISBN 978-981-334-025-1. OCLC 1243534370.

- McAllister, Ian (1994). The Rise of New Politics and Market Liberalism in Australia and New Zealand. British Journal of Political Science. pp. 381–402.

- Chiu, Osmond (27 July 2020). "Locking out the Left: The Emergence of National Factions in Australian Labor". Jacobin. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- Marin-Guzman, David (16 December 2018). "Inside the union factions that rule the ALP conference". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Donor Summary by Party Group". periodicdisclosures.aec.gov.au. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Donor Summary by Party". periodicdisclosures.aec.gov.au. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Australian Electoral Commission Donor to Political Party Disclosure Return". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- "Chinese man tops list of Australian political donorsReturn". The Australianaccess-date=22 April 2021.

- Ting, Heath Aston, Matthew Knott and Inga (2 February 2015). "Mystery Chinese donor Zi Chun Wang tops political donations with $850,000 gift to Labor". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- "Chinese man tops list of Australian political donorsReturn". The Australian. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- "Australian political donations: Who gave how much?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 24 October 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "Slush fund royal commission: the labour movement faces its demons". 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "Bill Shorten: Campaign for Labor leadership received money from allegedly dodgy, multi-million-dollar-union slush fund". Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "Union set up Labor slush fund, court told". Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- Knowles, Lorna (27 March 2019). "Gun lobby's 'concerted and secretive' bid to undermine Australian laws". ABC News. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

Bibliography

- Bramble, Tom, and Rick Kuhn. Labor's Conflict: Big Business, Workers, and the Politics of Class (Cambridge University Press; 2011) 240 pages.

- Calwell, A. A. (1963). Labor's Role in Modern Society. Melbourne, Lansdowne Press.

- Faulkner, John; Macintyre, Stuart (2001). True Believers – The story of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-609-6.

- McKinlay, Brian (1981). The ALP: A Short History of the Australian Labor Party. Melbourne: Drummond/Heinemann. ISBN 0-85859-254-1.

- McMullin, Ross (1991). The Light on the Hill: The Australian Labor Party 1891–1991. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia. ISBN 0-19-553451-4.

External links

- Australian Labor Party Victorian Branch Rules, April 2013

- Manifesto of the Queensland Labour Party, 1892 - UNESCO Australian Memory of the World Register

- 125th anniversary of the Manifesto of the Queensland Labour Party - John Oxley Library Blog, State Library of Queensland.

- OM69-18 Charles Seymour Papers 1880-1924 - Collection record, State Library of Queensland

- Charles Seymour Papers 1880-1924: Treasure collection of the John Oxley Library - John Oxley Library Blog, State Library of Queensland.