Angioplasty

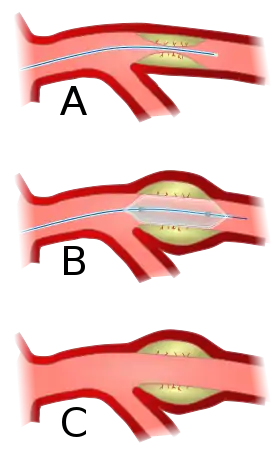

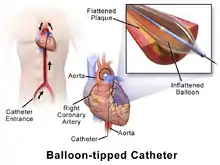

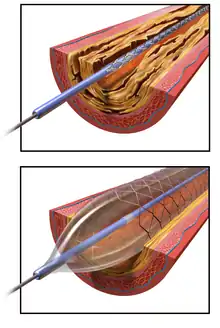

Angioplasty, is also known as balloon angioplasty and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA), is a minimally invasive endovascular procedure used to widen narrowed or obstructed arteries or veins, typically to treat arterial atherosclerosis.[1] A deflated balloon attached to a catheter (a balloon catheter) is passed over a guide-wire into the narrowed vessel and then inflated to a fixed size.[1] The balloon forces expansion of the blood vessel and the surrounding muscular wall, allowing an improved blood flow.[1] A stent may be inserted at the time of ballooning to ensure the vessel remains open, and the balloon is then deflated and withdrawn.[2] Angioplasty has come to include all manner of vascular interventions that are typically performed percutaneously.

| Angioplasty | |

|---|---|

Balloon angioplasty | |

| ICD-9-CM | 00.6, 36.0 39.50 |

| MeSH | D017130 |

| LOINC | 36760-7 |

The word is composed of the combining forms of the Greek words ἀνγεῖον angeîon "vessel" or "cavity" (of the human body) and πλάσσω plássō "form" or "mould".

Uses and indications

Coronary angioplasty

A coronary angioplasty is a therapeutic procedure to treat the stenotic (narrowed) coronary arteries of the heart found in coronary heart disease.[1] These stenotic segments of the coronary arteries arise due to the buildup of cholesterol-laden plaques that form in a condition known as atherosclerosis.[3] A percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or coronary angioplasty with stenting, is a non-surgical procedure used to improve the blood flow to the heart.[1]

Coronary Angioplasty is indicated for coronary artery disease such as unstable angina, NSTEMI, STEMI and spontaneous coronary artery perforation.[1] PCI for stable coronary disease has been shown to significantly relieve symptoms such as angina, or chest pain, thereby improving functional limitations and quality of life.[4]

Peripheral angioplasty

Peripheral angioplasty refers to the use of a balloon to open a blood vessel outside the coronary arteries. It is most commonly done to treat atherosclerotic narrowings of the abdomen, leg and renal arteries caused by peripheral artery disease. Often, peripheral angioplasty is used in conjunction with guide wire, peripheral stenting and an atherectomy.[5]

Chronic limb-threatening ischemia

Angioplasty can be used to treat advanced peripheral artery disease to relieve the claudication, or leg pain, that is classically associated with the condition.[6]

The bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischemia of the leg (BASIL) trial investigated infrainguinal bypass surgery first compared to angioplasty first in select patients with severe lower limb ischemia who were candidates for either procedure. The BASIL trial found that angioplasty was associated with less short term morbidity compared with bypass surgery, however long term outcomes favor bypass surgery.[7]

Based on the BASIL trial, the ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend balloon angioplasty only for patients with a life expectancy of 2 years or less or those who do not have an autogenous vein available. For patients with a life expectancy greater than 2 of years life, or who have an autogenous vein, a bypass surgery could be performed first.[8]

Renal artery angioplasty

Renal artery stenosis is associated with hypertension and loss of renal function.[9] Atherosclerotic obstruction of the renal artery can be treated with angioplasty with or without stenting of the renal artery.[10] There is a weak recommendation for renal artery angioplasty in patients with renal artery stenosis and flash edema or congestive heart failure.[10]

Carotid angioplasty

Carotid artery stenosis can be treated with angioplasty and carotid stenting for patients at high risk for undergoing carotid endarterectomy (CEA).[11] Although carotid endarterectomy is typically preferred over carotid artery stenting, stenting is indicated in select patients with radiation-induced stenosis or a carotid lesion not suitable for surgery.[12]

Venous angioplasty

Angioplasty is used to treat venous stenosis affecting hemodialysis access, with drug-coated balloon angioplasty proving to have better 6 month and 12 month patency than conventional balloon angioplasty.[13] Angioplasty is occasionally used to treat residual subclavian vein stenosis following thoracic outlet decompression surgery for thoracic outlet syndrome.[14] There is a weak recommendation for deep venous stenting to treat obstructive chronic venous disease.[15]

Contraindications

Angioplasty requires an access vessel, typically the femoral or radial artery or femoral vein, to permit access to the vascular system for the wires and catheters used. If no access vessel of sufficient size and quality is available, angioplasty is contraindicated. A small vessel diameter, the presence of posterior calcification, occlusion, hematoma, or an earlier placement of a bypass origin, may make access to the vascular system too difficult.

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) is contraindicated in patients with left main coronary artery disease, due to the risk of spasm of the left main coronary artery during the procedure.[16] Also, PTCA is not recommended if there is less than 70% stenosis of the coronary arteries, as the stenosis it is not deemed to be hemodynamically significant below this level.[16]

Technique

Access to the vascular system is typically gained percutaneously (through the skin, without a large surgical incision). An introducer sheath is inserted into the blood vessel via the Seldinger technique.[17] Fluoroscopic guidance uses magnetic resonance or X-ray fluoroscopy and radiopaque contrast dye to guide angled wires and catheters to the region of the body to be treated in real time.[18] Tapered guidewire is chosen for small occlusion, followed by intermediate type guidewires for tortuous arteries and difficulty passing through extremely narrow channels, and stiff wires for hard, dense, and blunt occlusions.[19] To treat a narrowing in a blood vessel, a wire is passed through the stenosis in the vessel and a balloon on a catheter is passed over the wire and into the desired position.[20] The positioning is verified by fluoroscopy and the balloon is inflated using water mixed with contrast dye to 75 to 500 times normal blood pressure (6 to 20 atmospheres), with most coronary angioplasties requiring less than 10 atmospheres.[21] A stent may or may not also be placed.

At the conclusion of the procedure, the balloons, wires and catheters are removed and the vessel puncture site is treated either with direct pressure or a vascular closure device.[22]

Transradial artery access (TRA) and transfemoral artery access (TFA) are two techniques for percutaneous coronary intervention.[23] TRA is the technique of choice for management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) as it has significantly lower incidence of bleeding and vascular complications compared with the TFA approach.[23] TRA also has a mortality benefit for high risk ACS patients and high risk bleeding patients.[23] TRA was also found to yield improved quality of life, as well as decreased healthcare costs and resources.[23]

Risks and complications

Relative to surgery, angioplasty is a lower-risk option for the treatment of the conditions for which it is used, but there are unique and potentially dangerous risks and complications associated with angioplasty:

- Embolization, or the launching of debris into the bloodstream[24]

- Bleeding from over-inflation of a balloon catheter or the use of an inappropriately large or stiff balloon, or the presence of a calcified target vessel.[24]

- Hematoma or pseudoaneurysm formation at the access site[24]

- Radiation-induced injuries (burns) from the X-rays used[25]

- Contrast-induced renal injury[26]

- Cerebral Hyperperfusion Syndrome leading to stroke is a serious complication of carotid artery angioplasty with stenting.[27]

Angioplasty may also provide a less durable treatment for atherosclerosis and be more prone to restenosis relative to vascular bypass or coronary artery bypass grafting.[28] Drug-eluting balloon angioplasty has significantly less restenosis, late lumen loss and target lesion revascularization at both short term and midterm follow-up compared to uncoated balloon angioplasty for femoropopliteal arterial occlusive disease.[29] Although angioplasty of the femoropopliteal artery with paclitaxel-coated stents and balloons significantly reduces rates of vessel restenosis and target lesion revascularization, it was also found to have increased risk of death.[30]

Recovery

After angioplasty, most patients are monitored overnight in the hospital, but if there are no complications, patients are sent home the following day.[26]

The catheter site is checked for bleeding and swelling and the heart rate and blood pressure are monitored to detect late rupture and hemorrhage.[26] Post-procedure protocol also involves monitoring urinary output, cardiac symptoms, pain and other signs of systemic problems.[26] Usually, patients receive medication that will relax them to protect the arteries against spasms. Patients are typically able to walk within two to six hours following the procedure and return to their normal routine by the following week.[31]

Angioplasty recovery consists of avoiding physical activity for several days after the procedure. Patients are advised to avoid heavy lifting and strenuous activities for a week.[32][33] Patients will need to avoid physical stress or prolonged sport activities for a maximum of two weeks after a delicate balloon angioplasty.[34]

After the initial two week recovery phase, most angioplasty patients can begin to safely return to low-level exercise. A graduated exercise program is recommended whereby patients initially perform several short bouts of exercise each day, progressively increasing to one or two longer bouts of exercise.[35] As a precaution, all structured exercise should be cleared by a cardiologist before commencing. Exercise-based rehabilitation following percutaneous coronary intervention has shown improvement in recurrent angina, total exercise time, ST-segment decline, and maximum exercise tolerance.[36]

Patients who experience swelling, bleeding or pain at the insertion site, develop fever, feel faint or weak, notice a change in temperature or color in the arm or leg that was used or have shortness of breath or chest pain should immediately seek medical advice.

Patients with stents are usually prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) which consists of a P2Y12 inhibitor, such as clopidogrel, which is taken at the same time as acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin).[37] Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is recommended for 1 month following bare metal stent placement, for 3 months following a second generation drug-eluting stent placement, and for 6–12 months following a first generation drug-eluting stent placement.[1] DAPT's antiplatelet properties are intended to prevent blood clots, however they also increase the risk of bleeding, so it is important to consider each patient's preferences, cardiac conditions, and bleeding risk when determining the duration of DAPT treatment.[37] Another important consideration is that concomitant use of Clopidogrel and Proton Pump Inhibitors following coronary angiography is associated with significantly higher adverse cardiovascular complications such as major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction.[38]

History

Angioplasty was first described by the US interventional radiologist Charles Dotter in 1964.[39] Dr. Dotter pioneered modern medicine with the invention of angioplasty and the catheter-delivered stent, which were first used to treat peripheral arterial disease. On January 16, 1964, Dotter percutaneously dilated a tight, localized stenosis of the subsartorial artery in an 82-year-old woman with painful leg ischemia and gangrene who refused leg amputation. After successful dilation of the stenosis with a guide wire and coaxial Teflon catheters, the circulation returned to her leg. The dilated artery stayed open until her death from pneumonia two and a half years later.[40] Charles Dotter is commonly known as the "Father of Interventional Radiology" and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1978.

The first percutaneous coronary angioplasty on an awake patient was performed in Zurich by the German cardiologist Andreas Gruentzig on September 16, 1977.[41]

Dr. Simon H. Stertzer was the first to perform coronary angioplasty in the United States on March 1, 1978, at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. That same day, Dr. Richard K. Myler of St. Mary's Hospital in San Francisco performed the second coronary angioplasty in the United States.

The initial form of angioplasty was 'plain old balloon angioplasty' (POBA) without stenting, until the invention of bare metal stenting in the mid-1980s to prevent the early restenosis observed with POBA.[1]

Bare metal stents were found to cause in-stent restenosis as a result of neointimal hyperplasia and stent thrombosis, which led to the invention of drug-eluting stents with anti-proliferative drugs to combat in-stent restenosis.[1]

The first coronary angioplasty with a drug delivery stent system was performed by Dr. Stertzer and Dr. Luis de la Fuente, at the Instituto Argentino de Diagnóstico y Tratamiento (English: Argentina Institute of Diagnosis and Treatment[42]) in Buenos Aires, in 1999.

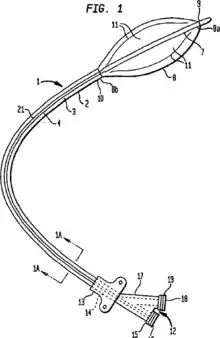

Ingemar Henry Lundquist invented the over-the-wire balloon catheter that is now used in the majority of angioplasty procedures in the world.[43]

References

- Chhabra, Lovely; Zain, Muhammad A.; Siddiqui, Waqas J. (2019), "Angioplasty", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29763069, retrieved January 20, 2020

- K, Marmagkiolis; C, Iliescu; Mmr, Edupuganti; M, Saad; Kd, Boudoulas; A, Gupta; N, Lontos; M, Cilingiroglu (December 2019). "Primary Patency With Stenting Versus Balloon Angioplasty for Arteriovenous Graft Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 31 (12): E356–E361. PMID 31786526.

- "Atheroscleoris". NHLBI.

- Arnold, Suzanne V. (2018). "Current Indications for Stenting: Symptoms or Survival CME". Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. 14 (1): 7–13. doi:10.14797/mdcj-14-1-7. ISSN 1947-6094. PMC 5880567. PMID 29623167.

- O, Abdullah; J, Omran; T, Enezate; E, Mahmud; N, Shammas; J, Mustapha; F, Saab; M, Abu-Fadel; R, Ghadban (June 2018). "Percutaneous Angioplasty Versus Atherectomy for Treatment of Symptomatic Infra-Popliteal Arterial Disease". Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine. 19 (4): 423–428. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2017.09.014. PMID 29269152. S2CID 36093380.

- Topfer, Leigh-Ann; Spry, Carolyn (2016), "New Technologies for the Treatment of Peripheral Artery Disease", CADTH Issues in Emerging Health Technologies, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, PMID 30148583, retrieved January 30, 2020

- Dj, Adam; Jd, Beard; T, Cleveland; J, Bell; Aw, Bradbury; Jf, Forbes; Fg, Fowkes; I, Gillepsie; Cv, Ruckley (December 3, 2005). "Bypass Versus Angioplasty in Severe Ischaemia of the Leg (BASIL): Multicentre, Randomised Controlled Trial". Lancet. 366 (9501): 1925–34. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67704-5. PMID 16325694. S2CID 54229954.

- Tw, Rooke; At, Hirsch; S, Misra; An, Sidawy; Ja, Beckman; Lk, Findeiss; J, Golzarian; Hl, Gornik; Jl, Halperin (November 1, 2011). "2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guideline for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease (Updating the 2005 Guideline): A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 58 (19): 2020–45. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.023. PMC 4714326. PMID 21963765.

- G, Raman; Gp, Adam; Cw, Halladay; Vn, Langberg; Ia, Azodo; Em, Balk (November 1, 2016). "Comparative Effectiveness of Management Strategies for Renal Artery Stenosis: An Updated Systematic Review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 165 (9): 635–649. doi:10.7326/M16-1053. PMID 27536808.

- van den Berg, Danielle T. N. A.; Deinum, Jaap; Postma, Cornelis T.; van der Wilt, Geert Jan; Riksen, Niels P. (July 2012). "The efficacy of renal angioplasty in patients with renal artery stenosis and flash oedema or congestive heart failure: a systematic review". European Journal of Heart Failure. 14 (7): 773–781. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfs037. ISSN 1879-0844. PMID 22455866.

- Ahn, Sun Ho; Prince, Ethan A.; Dubel, Gregory J. (September 2013). "Carotid Artery Stenting: Review of Technique and Update of Recent Literature". Seminars in Interventional Radiology. 30 (3): 288–296. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1353482. ISSN 0739-9529. PMC 3773038. PMID 24436551.

- S, Giannopoulos; P, Texakalidis; Ak, Jonnalagadda; T, Karasavvidis; S, Giannopoulos; Dg, Kokkinidis (July 2018). "Revascularization of Radiation-Induced Carotid Artery Stenosis With Carotid Endarterectomy vs. Carotid Artery Stenting: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine. 19 (5 Pt B): 638–644. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2018.01.014. PMID 29422277. S2CID 46801250.

- Ij, Yan Wee; Hy, Yap; Lt, Hsien Ts'ung; S, Lee Qingwei; Cs, Tan; Ty, Tang; Tt, Chong (September 2019). "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Drug-Coated Balloon Versus Conventional Balloon Angioplasty for Dialysis Access Stenosis". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 70 (3): 970–979.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2019.01.082. PMID 31445651.

- Db, Schneider; Pj, Dimuzio; Nd, Martin; Rl, Gordon; Mw, Wilson; Jm, Laberge; Rk, Kerlan; Cm, Eichler; Lm, Messina (October 2004). "Combination Treatment of Venous Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Open Surgical Decompression and Intraoperative Angioplasty". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 40 (4): 599–603. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.028. PMID 15472583.

- Seager, M. J.; Busuttil, A.; Dharmarajah, B.; Davies, A. H. (January 2016). "Editor's Choice-- A Systematic Review of Endovenous Stenting in Chronic Venous Disease Secondary to Iliac Vein Obstruction". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 51 (1): 100–120. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.09.002. ISSN 1532-2165. PMID 26464055.

- Malik, Talia F.; Tivakaran, Vijai S. (2019), "Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty (PTCA)", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30571038, retrieved January 23, 2020

- L, Thaut; W, Weymouth; B, Hunsaker; D, Reschke (January 2019). "Evaluation of Central Venous Access With Accelerated Seldinger Technique Versus Modified Seldinger Technique". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 56 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.10.021. PMID 30503723. S2CID 54484203.

- Saeed, Maythem; Hetts, Steve W.; English, Joey; Wilson, Mark (January 2012). "MR fluoroscopy in vascular and cardiac interventions (review)". The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 28 (1): 117–137. doi:10.1007/s10554-010-9774-1. ISSN 1569-5794. PMC 3275732. PMID 21359519.

- Dash D (2016). "Guidewire crossing techniques in coronary chronic total occlusion intervention: A to Z". Indian Heart Journal. 68 (3): 410–20. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2016.02.019. PMC 4912030. PMID 27316507.

- Ali, Ronan; Greenbaum, Adam B.; Kugelmass, Aaron D. (January 14, 2012). "A Review of Available Angioplasty Guiding Catheters, Wires and Balloons - Making the Right Choice". Journal - A Review of Available Angioplasty Guiding Catheters, Wires and Balloons - Making the Right Choice.

- Jk, Kahn; Bd, Rutherford; Dr, McConahay; Go, Hartzler (November 1990). "Inflation Pressure Requirements During Coronary Angioplasty". Catheterization and Cardiovascular Diagnosis. 21 (3): 144–7. doi:10.1002/ccd.1810210304. PMID 2225048.

- McTaggart, R. A.; Raghavan, D.; Haas, R. A.; Jayaraman, M. V. (June 1, 2010). "StarClose Vascular Closure Device: Safety and Efficacy of Deployment and Reaccess in a Neurointerventional Radiology Service". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 31 (6): 1148–1150. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2001. ISSN 0195-6108. PMC 7963929. PMID 20093310.

- Mason Peter J.; Shah Binita; Tamis-Holland Jacqueline E.; Bittl John A.; Cohen Mauricio G.; Safirstein Jordan; Drachman Douglas E.; Valle Javier A.; Rhodes Denise; Gilchrist Ian C. (September 1, 2018). "An Update on Radial Artery Access and Best Practices for Transradial Coronary Angiography and Intervention in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 11 (9): e000035. doi:10.1161/HCV.0000000000000035. PMID 30354598. S2CID 53031413.

- Jongkind, Vincent; Akkersdijk, George J. M.; Yeung, Kak K.; Wisselink, Willem (November 2010). "A systematic review of endovascular treatment of extensive aortoiliac occlusive disease". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 52 (5): 1376–1383. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2010.04.080. ISSN 1097-6809. PMID 20598474.

- Calma, D (May 6, 2004). "Cardiologists are briefed about radiation risks". IAEA. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- "Guidelines for Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 1 (1): 5–15. November 1, 1990. doi:10.1016/S1051-0443(90)72494-3. ISSN 1051-0443.

- Huibers, Anne E.; Westerink, Jan; de Vries, Evelien E.; Hoskam, Anne; den Ruijter, Hester M.; Moll, Frans L.; de Borst, Gert J. (September 2018). "Editor's Choice - Cerebral Hyperperfusion Syndrome After Carotid Artery Stenting: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 56 (3): 322–333. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.05.012. ISSN 1532-2165. PMID 30196814.

- A, Kayssi; W, Al-Jundi; G, Papia; Ds, Kucey; T, Forbes; Dk, Rajan; R, Neville; Ad, Dueck (January 26, 2019). "Drug-eluting Balloon Angioplasty Versus Uncoated Balloon Angioplasty for the Treatment of In-Stent Restenosis of the Femoropopliteal Arteries". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD012510. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012510.pub2. PMC 6353053. PMID 30684445.

- Jongsma, Hidde; Bekken, Joost A.; de Vries, Jean-Paul P. M.; Verhagen, Hence J.; Fioole, Bram (November 2016). "Drug-eluting balloon angioplasty versus uncoated balloon angioplasty in patients with femoropopliteal arterial occlusive disease". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 64 (5): 1503–1514. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2016.05.084. ISSN 1097-6809. PMID 27478005.

- K, Katsanos; S, Spiliopoulos; P, Kitrou; M, Krokidis; D, Karnabatidis (December 18, 2018). "Risk of Death Following Application of Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons and Stents in the Femoropopliteal Artery of the Leg: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Journal of the American Heart Association. 7 (24): e011245. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.011245. PMC 6405619. PMID 30561254.

- "What should I expect after my procedure?". Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Recovery - Coronary angioplasty and stent insertion". National Health Service, UK. June 11, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2019. Page last reviewed: 28/08/2018

- "Coronary angioplasty and stents". Mayo Clinic.

- "Angioplasty Recovery". Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Exercise Guidelines After Angioplasty". Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- Yang, Xinyu; Li, Yanda; Ren, Xiaomeng; Xiong, Xingjiang; Wu, Lijun; Li, Jie; Wang, Jie; Gao, Yonghong; Shang, Hongcai; Xing, Yanwei (March 17, 2017). "Effects of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Scientific Reports. 7: 44789. Bibcode:2017NatSR...744789Y. doi:10.1038/srep44789. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5356037. PMID 28303967.

- Smith, Sidney C.; Smith, Peter K.; Sabatine, Marc S.; O'Gara, Patrick T.; Newby, L. Kristin; Mukherjee, Debabrata; Mehran, Roxana; Mauri, Laura; Mack, Michael J.; Lange, Richard A.; Granger, Christopher B.; Fleisher, Lee A.; Fihn, Stephan D.; Brindis, Ralph G.; Bittl, John A.; Bates, Eric R.; Levine, Glenn N. (September 6, 2016). "ACC/AHA Guideline Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in CAD Patients". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 68 (10): 1082–1115. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.513. PMID 27036918. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- Bundhun, Pravesh Kumar; Teeluck, Abhishek Rishikesh; Bhurtu, Akash; Huang, Wei-Qiang (January 5, 2017). "Is the concomitant use of clopidogrel and Proton Pump Inhibitors still associated with increased adverse cardiovascular outcomes following coronary angioplasty?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recently published studies (2012 - 2016)". BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 17 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s12872-016-0453-6. ISSN 1471-2261. PMC 5221663. PMID 28056809.

- Dotter CT, Judkins MP (November 1964). "Transluminal treatment of arteriosclerotic obstruction". Circulation. 30 (5): 654–70. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.30.5.654. PMID 14226164.

- Rösch, Josef; et al. (2003). "The birth, early years, and future of interventional radiology". J Vasc Interv Radiol. 14 (7): 841–853. doi:10.1097/01.RVI.0000083840.97061.5b. PMID 12847192. S2CID 14197760.

- "Andreas R. Gruentzig – Biographical Sketch". ptca.org. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- "Argentina Institute of Diagnosis and Treatment (IADT), Argentina / Institution outputs / Nature Index". NatureIndex.com. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- "System for filling and inflating and deflating a vascular dilating cathether assembly". patents.com. patents.com. Retrieved July 8, 2013.