Bangor, County Down

Bangor (/ˈbæŋɡər/ BANG-gər;[4] from Irish: Beannchar [ˈbʲaːn̪ˠəxəɾˠ])[5] is a town[lower-alpha 1] in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is a seaside resort on the southern side of Belfast Lough and within the Belfast Metropolitan Area. It functions as a commuter town for the Greater Belfast area, which it is linked to by the A2 road and the Belfast–Bangor railway line. Bangor is situated 13.6 miles (22 km) east from the heart of Belfast. The population was 61,011 at the 2011 Census.[6]

| Bangor | |

|---|---|

| Town[lower-alpha 1] | |

View of Bangor at night, from the Long Hole | |

Coat of Arms of Bangor | |

Bangor Location within County Down | |

| Population | 61,011 (2011 Census) |

| • Belfast | 13 mi (21 km) |

| District |

|

| County |

|

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BANGOR |

| Postcode district | BT19 BT20 |

| Dialling code | 028 |

| Police | Northern Ireland |

| Fire | Northern Ireland |

| Ambulance | Northern Ireland |

| UK Parliament |

|

| NI Assembly |

|

Bangor is part of the North Down constituency. Tourism is important to the local economy, particularly in the summer months, and plans are being made for the long-delayed redevelopment of the seafront; a notable historical building in the town is Bangor Old Custom House. The largest plot of private land in the area, the Clandeboye Estate, which is located a few miles from the town centre, belonged to the Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava. Bangor hosts the Royal Ulster and Ballyholme yacht clubs. Bangor Marina is one of the largest in both Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland, and holds Blue Flag status.[7] The town is twinned with Bregenz in Austria and Virginia Beach in the United States.

On 20 May 2022, it was announced that, as part of the Platinum Jubilee Civic Honours, Bangor would be granted city status by Letters Patent later in 2022.[8] It will join Northern Ireland's current cities, Armagh, Belfast, Derry, Lisburn, and Newry.

Name

The town was originally called Inver Beg after the now culverted stream which ran past the abbey.[9] The place, also Inber Bece,[10] as an ancient name alluded to the finding of the skull of Bece, a pet dog, of one Bredcán or Brecán after his shipwreck. This drowning was linked back to the name of the whirlpool of Core Brecain, then understood to be located off Rathlin Island. The name Bangor is derived from the Irish word Beannchor (modern Irish Beannchar) meaning a horned or peaked curve or perhaps a staked enclosure, as the shape of Bangor Bay resembles the horns of a bull. It may also be linked to Beanna, Irish for cliffs. The area was also known as The Vale of Angels, as Saint Patrick once rested there and is said to have had a vision filled with angels.[11]

Coat of arms

The shield is emblazoned with two ships, which feature the Red Hand of Ulster on their sails, denoting that Bangor is in the province of Ulster. The blue and white stripes on the shield show that Bangor is a seaside town. Supporting the shield are two sharks, signifying Bangor's links with the sea. Each is charged with a gold roundel; the left featuring a shamrock to represent Ireland, and the right featuring a bull's head, possibly in reference to the derivation of the town's name. The arms are crested by a haloed St Comgall, founder of the town's abbey, who was an important figure in the spread of Christianity. The motto reads Beannchor, the archaic form of the town's name in Irish.[12]

History

.jpg.webp)

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1821 | 2,943 | — |

| 1831 | 2,741 | −6.9% |

| 1841 | 3,116 | +13.7% |

| 1851 | 2,849 | −8.6% |

| 1861 | 2,531 | −11.2% |

| 1871 | 2,560 | +1.1% |

| 1881 | 3,006 | +17.4% |

| 1891 | 3,834 | +27.5% |

| 1901 | 5,903 | +54.0% |

| 1911 | 7,776 | +31.7% |

| 1926 | 13,311 | +71.2% |

| 1937 | 15,769 | +18.5% |

| 1951 | 20,610 | +30.7% |

| 1961 | 23,862 | +15.8% |

| 1966 | 26,921 | +12.8% |

| 1971 | 35,260 | +31.0% |

| 1981 | 46,585 | +32.1% |

| 1991 | 52,437 | +12.6% |

| 2001 | 58,388 | +11.3% |

| 2011 | 61,011 | +4.5% |

| [6][13][14][15][16][17] | ||

Bangor has a long and varied history, from the Bronze Age people whose swords were discovered in 1949 or the Viking burial found on Ballyholme beach, to the Victorian pleasure seekers who travelled on the new railway from Belfast to take in the sea air. The town has been the site of a monastery renowned throughout Europe for its learning and scholarship, the victim of violent Viking raids in the 8th and 9th centuries, and the new home of Scottish and English planters during the Plantation of Ulster.[18]

Bangor Abbey

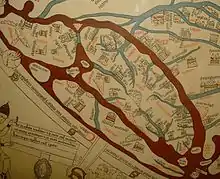

The Annals of Ulster mentions that the monastery of Bangor was founded by Saint Comgall in approximately 555[19] and was where the Antiphonarium Benchorense was written, a copy of which can be seen in the town's heritage centre. The monastery had such widespread influence that the town is one of only four places in Ireland to be named in the Hereford Mappa Mundi in 1300. The monastery, situated roughly where the Church of Ireland Bangor Abbey stands at the head of the town, became a centre of great learning and was among the most eminent of Europe's missionary institutions in the Early Middle Ages, although it also suffered greatly at the hands of Viking raiders in the 8th century and the 9th century.[20]

Saint Malachy was elected Abbot of the monastery in 1123, a year before being consecrated Bishop of Connor. His extensive travels around Europe inspired him to rejuvenate the monasteries in Ireland, and he replaced the existing wooden huts with stone buildings.[21]

Bangor's founder, Comgall, was born in Antrim in 517. Originally a soldier, he took monastic vows and was educated for his new life. He is next seen in the Irish annals as a hermit on Lough Erne, however his rule was so severe that seven of his fellow monks died. He was persuaded to leave and establish a house at Bangor (or Beannchar, from the Irish "Horned Curve", probably in reference to the bay) in the Vale of the Angels. The earliest Irish annals give 558 as the date of Bangor's commencement.[22]

Bangor Mór and Perpetual Psalmody

At Bangor, Comgall instituted a rigid monastic rule of incessant prayer and fasting. Far from turning people away, this ascetic rule attracted thousands. When Comgall died in 602, the annals report that three thousand monks looked to him for guidance. Bangor Mór, named "the great Bangor" to distinguish it from its British contemporaries, became the greatest monastic school in Ulster as well as one of the three leading lights of Celtic Christianity. The others were Iona, the great missionary centre founded by Columba, and Bangor on the Dee, founded by Dinooth; the ancient Welsh Triads also confirm the "Perpetual Harmonies" at the house.[23]

Throughout the sixth century, Bangor became famous for its choral psalmody. "It was this music which was carried to the continent by the Bangor missionaries in the following century".[24] Divine services of the seven hours of prayer were carried out throughout Bangor's existence, however the monks went further and carried out the practice of laus perennis. In the twelfth century, Bernard of Clairvaux spoke of Comgall and Bangor, stating, "the solemnization of divine offices was kept up by companies, who relieved each other in succession, so that not for one moment day and night was there an intermission of their devotions." This continuous singing was antiphonal in nature, based on the call and response reminiscent of Patrick's vision, but also practised by St. Martin's houses in France. Many of these psalms and hymns were later written down in the Antiphonary of Bangor which came to reside in Colombanus' monastery at Bobbio, Italy.[25]

The Bangor Missionaries

In 580, a Bangor monk named Mirin took Christianity to Paisley in the west of Scotland, where he died "full of sanctity and miracles". In 590, the fiery Colombanus, one of Comgall's leaders, set out from Bangor with twelve other brothers, including Saint Gall who planted monasteries throughout Switzerland. In Burgundy, Columbanus established a severe monastic rule at Luxeuil which mirrored that of Bangor. From there he went to Bobbio in Italy and established the house which became one of the largest monasteries in Europe.[26]

17th and 18th centuries

The modern town had its origins in the early 17th century when James Hamilton, a Lowland Scot, arrived in Bangor, having been granted lands in North Down by King James VI and I in 1605. In 1612, King James made Bangor a borough which permitted it to elect two MPs to the Irish Parliament in Dublin.[27] The Old Custom House, which was completed by Hamilton in 1637 after James I granted Bangor the status of a port in 1620, is a visible reminder of the new order introduced by Hamilton and his Scots settlers.[28]

In 1689 during the Williamite War in Ireland, Marshal Schomberg's expedition landed at Ballyholme Bay and captured Bangor, before going on to besiege Carrickfergus. Schomberg's force went south to Dundalk Camp and were present at the Battle of the Boyne the following year.[29]

The town was an important source of customs revenue for the Crown and in the 1780s Colonel Robert Ward improved the harbour and promoted the cotton industries; today's seafront was the location of several large steam-powered cotton mills, which employed a large workforce.[30]

The end of the 18th century was a time of great political and social turmoil in Ireland, as the United Irishmen, inspired by the American and French Revolutions, sought to achieve a greater degree of independence from Britain. On the morning of 10 June 1798 a force of United Irishmen, mainly from Bangor, Donaghadee, Greyabbey and Ballywalter attempted to occupy the nearby town of Newtownards. They met with musket fire from the market house and were subsequently defeated.[31][32]

Victorian era

By the middle of the 19th century, the cotton mills had declined and the town changed in character once again. The laying of the railway in 1865 meant that inexpensive travel from Belfast was possible, and working-class people could afford for the first time to holiday in the town. Bangor soon became a fashionable resort for Victorian holidaymakers, as well as a desirable home to the wealthy. Many of the houses overlooking Bangor Bay (some of which have been demolished to make way for modern flats) date from this period. The belief in the restorative powers of the sea air meant that the town became a location for sea bathing and marine sports, and the number of visitors from Great Britain increased during the Edwardian era at the beginning of the 20th century, which also saw the improvement of Ward Park.[33]

20th century to present

.jpg.webp)

The inter-war period of the early 20th century saw the development of the Tonic Cinema, Pickie Pool and Caproni's ballroom. All three were among the foremost of their type in Ireland, although they no longer exist. However, there is a park which replaced Pickie Pool named Pickie Fun Park. A children's paddling pool was created as the original Pickie Pool was demolished due to the rejuvenation of Bangor seafront in the 1980s and early 1990s. Pickie Fun Park closed in early 2011 to be refurbished and modernised. The park, which reopened in March 2012, boasts an 18-hole maritime themed mini golf course, children's electric cars and splash pads (replacing the old children's paddling pool). Also, the Pickie Puffer steam train has been given an enhanced route while the swans have a brand new lagoon.[34]

During World War II, General Dwight D. Eisenhower addressed Allied troops in Bangor, who were departing to take part in the D-Day landings. In 2005, his granddaughter Mary-Jean Eisenhower came to the town to oversee the renaming of the marina's North Pier to the Eisenhower Pier.[35]

With the growing popularity of inexpensive foreign holidays from the 1960s onwards, Bangor declined as a tourist resort and was forced to rethink its future. The second half of the 20th century saw its role as a dormitory town for Belfast become more important. Its population increased dramatically; from around 14,000 in 1930 it had reached 40,000 by 1971 and 58,000 by the end of the century (the 2001 census showed the population as 76,403).[36]

The 1970s saw the building of the Springhill Shopping Centre, an out–of–town development near the A2 road to Belfast and Northern Ireland's first purpose-built shopping centre. It has been demolished to facilitate a modern Tesco supermarket.[37]

In the early 1990s, Bloomfield Shopping Centre, another out–of–town development, opened beside Bloomfield Estate. In 2007, a major renovation of the centre began, including the construction of a multistorey car park. The trend towards out–of–town shopping centres was somewhat reversed with the construction of the Flagship Centre around 1990. The Flagship Centre went into administration and was closed in January 2019, it is currently undergoing appraisal for re-development options.[38]

The former seafront of the town is awaiting redevelopment and has been for over two decades, with a large part of the frontage already demolished, leaving a patch of derelict ground facing onto the marina. A great deal of local controversy surrounds this process and the many plans put forward by the council and developers for the land. In November 2009 it was voted by UTV viewers as Ulster's Biggest Eyesore. A state of the art recycling centre has been built in Balloo Industrial Estate which is supposed to be one of the most advanced in Europe. It opened in the summer of 2008.[39][40]

On 20 May 2022, it was announced that, as part of the Platinum Jubilee Civic Honours, Bangor would be granted city status by Letters Patent later in 2022.[41]

The Troubles

Despite escaping much of the sectarian violence during The Troubles, Bangor was the site of some major incidents. During the troubles there were eight murders in the town including that of the first Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) woman to be murdered on duty; 26-year-old Mildred Harrison was killed by an explosion from a UVF bomb while on foot patrol in the High Street on 16 March 1975.[42] On 23 March 1972 the IRA detonated two large car bombs on the town's main street.[43]

On 30 March 1974, paramilitaries carried out a major incendiary bomb attack on the main shopping centre in Bangor.[44][45] On 21 October 1992, an IRA unit from the lower Ormeau exploded a 200-pound (91 kg) bomb in Main Street, causing large amounts of damage to nearby buildings.[46][47]

Main Street sustained more damage on 7 March 1993, when the IRA exploded a 500-pound (230 kg) car bomb. Four RUC officers were injured in the explosion; the cost of the damage was later estimated at £2 million, as there was extensive damage to retail premises and Trinity Presbyterian Church, as well as minor damage to the local Church of Ireland Parish Church and First Bangor Presbyterian Church.[48]

Governance

Bangor is administered by Ards and North Down Borough Council which is based at Bangor Castle.[49]

Economy

Bangor had an estimated Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the equivalent of $US678 million in 2015.[50]

Geography

Bangor lies on the east coast of Northern Ireland, on the south shore of the mouth of Belfast Lough, north east of central Belfast.

Ballyholme Bay

The sea area to the north east of Bangor is Ballyholme Bay, named for the township of Ballyholme in the east of the town. During World War II the bay was used as a base for American troops training for the Normandy Landings.[51] Two ships have been named SS Ballyholme Bay. In 1903 a Viking grave was found on the shore at Ballyholme Bay: it contained two bronze brooches, a bowl, a fragment of chain and some textile material.[52] It has been said that "Ballyholme Bay is a sheltered bay and studies have suggested that it is one of the best landing places on Belfast Lough and would therefore have made a good location for a Viking base. It is possible that the burial was associated with a Viking settlement in the area."[53] In 1689 Field Marshal Schomberg landed with 10,000 troops either at Ballyholme Bay or at Groomsport, a little further east.[54]

Demography

2011 Census

On Census day (27 March 2011) there were 61,011 people living in Bangor, accounting for 3.37% of the NI total.[6] Of these:

- 18.83% were aged under 16 years and 17.40% were aged 65 and over;

- 52.14% of the usually resident population were female and 47.86% were male;

- 74.84% belong to or were brought up in a 'Protestant and Other Christian (including Christian related)' religion and 11.99% belong to or were brought up in the Catholic Christian faith.

- 72.51% indicated that they had a British national identity, 32.95% had a Northern Irish national identity and 8.05% had an Irish national identity (respondents could indicate more than one national identity);

- 41 years was the average (median) age of the population;

- 7.94% had some knowledge of Ulster-Scots and 2.72% had some knowledge of Irish (Gaelic).

Education

Colleges and schools in the area include South Eastern Regional College, Bangor Academy and Sixth Form College, Bangor Grammar School, Glenlola Collegiate School, and St Columbanus' College. Primary schools include Towerview Primary School, Clandeboye Primary, Ballyholme Primary School, Kilmaine Primary, St Malachy's Primary, St Comgall's Primary, Grange Park Primary, Ballymagee Primary, Bloomfield Primary, Kilcooley Primary, Rathmore Primary, Towerview Primary, and Bangor Central Integrated Primary School.

There are also a number of secondary, grammar, and primary schools in nearby towns and the vicinity of Bangor such as Crawfordsburn Primary & Groomsport Primary; Priory Integrated College, Sullivan Upper School, Regent House Grammar School, Movilla High School, Strangford College, Campbell College, and Rockport School are secondary schools.

Places of interest

- Bangor Marina

- Clandeboye Estate

- Ward Park

- Clandeboye Park

- Castle Park

- Bangor Abbey

- Bangor Carnegie Library

- Bangor Castle

- Somme Heritage Centre

- Bangor Market House, which dates from the late 18th century, is a 5-bay 2-storey building currently used as a bank

- Bangor Old Custom House

- McKee Clock

- Bangor walled garden

Climate

Like the rest of Northern Ireland, Bangor has a mild climate with few extremes of weather. It enjoys one of the sunniest climates in Northern Ireland, and receives about 900 millimetres (35 in) of rain per year, which is moderate by Ireland's standards. Snow is rare but occurs at least once or twice in an average winter and frost is not as severe as areas further inland. This is due to the mild winters and close proximity to the sea. Winter maxima are about 8 °C (46 °F) but can reach as high as 15 °C (59 °F). Average maxima in summer are around 20 °C (68 °F), although the record high is 30 °C (86 °F). The lowest recorded temperature is −8 °C (18 °F). Temperatures above 25 °C (77 °F) in Bangor can be uncomfortable due to the high humidity, with an apparent temperature in the high 20s. The climate puts Bangor in USDA plant hardiness zone 9a.

| Climate data for Bangor, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15 (59) |

15 (59) |

20 (68) |

23 (73) |

27 (81) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

26 (79) |

21 (70) |

19 (66) |

16 (61) |

30 (86) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8 (46) |

8 (46) |

9 (48) |

12 (54) |

15 (59) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

17 (63) |

14 (57) |

11 (52) |

9 (48) |

13 (55) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3 (37) |

3 (37) |

4 (39) |

5 (41) |

7 (45) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

5 (41) |

4 (39) |

6 (43) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7 (19) |

−8 (18) |

−6 (21) |

−4 (25) |

0 (32) |

2 (36) |

7 (45) |

5 (41) |

0 (32) |

−2 (28) |

−6 (21) |

−8 (18) |

−8 (18) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 99 (3.9) |

68 (2.7) |

79 (3.1) |

55 (2.2) |

59 (2.3) |

60 (2.4) |

56 (2.2) |

79 (3.1) |

80 (3.1) |

94 (3.7) |

88 (3.5) |

96 (3.8) |

913 (35.9) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 46 | 54 | 96 | 133 | 168 | 210 | 190 | 155 | 114 | 92 | 55 | 43 | 1,356 |

| Source: Met Office[55] | |||||||||||||

Bangor has had a number of extreme weather events, including hot summers in 2006, 2013 and 2018. The summers of 2007, 2008 and 2009 were some of the wettest on records with flooding in June 2007. The Autumn of 2006 was also the warmest recorded. December 2010 saw record snowfall fall on the town, with temperatures below −7 °C (19 °F). On 21 December 2010 an unofficial weather station manned by a retired meteorological officer in the Springhill area recorded a low of −8.1 °C (17.4 °F), and a high of −2.0 °C (28.4 °F). Snow lay to a level depth of 24 cm (9.4 in), the same morning. Inland Northern Ireland saw almost −19 °C (−2 °F), new record lows. Like much of the UK, spring 2020 was the sunniest on record.

Transport

Rail

The first section of Belfast and County Down Railway line from Belfast to Holywood opened in 1848 and was extended to Bangor by the Belfast, Holywood and Bangor Railway (BHBR), opening on 1 May 1865, along with Bangor railway station. It was acquired by the BCDR in 1884.[56] and closed to goods traffic on 24 April 1950.[57] Bangor West railway station was opened by the Belfast and County Down Railway on 1 June 1928.[57]

Bus

Bangor is served by Ulsterbus, which aside from local town services, provides daily services to Belfast, Newtownards, Holywood and Donaghadee.

Sport

Football

In football, NIFL Championship sides Ards and Bangor play at Clandeboye Park on Clandeboye Road.[58]

Hockey

Bangor has two hockey clubs that cater for both men's and women's hockey, respectively:

- Bangor Ladies Hockey Club : Bangor Ladies run three teams playing in Ulster Hockey Senior 3, Junior 7 and Junior 8b

- Bangor Mens Hockey Club : Bangor Mens run five teams with the 1st XI playing in the Ulster Hockey Premiership

Rugby Union

Bangor RFC plays in division 2C of the All-Ireland league at Upritchard Park.

Sailing

Bangor has clubs such as the Royal Ulster Yacht Club and Ballyholme Yacht Club which is the venue for Northern Ireland's Elite Sailing Facility.

Other sports

Bangor Aurora Aquatic and Leisure Complex includes Northern Ireland's only Olympic-size swimming pool.[59]

Music

The town has created an environment which has supported local musicians, such as Foy Vance and Snow Patrol.[60]

Notable people

- Iain Archer, musician (Snow Patrol)

- Jo Bannister, author and newspaper editor (County Down Spectator)

- Colin Bateman, author, screenwriter and journalist attended Bangor Grammar School (County Down Spectator)

- Edward Bingham, soldier; Victoria Cross recipient

- Colin Blakely, stage, film and TV actor

- Neil Brittain, news reporter

- Mike Bull, Commonwealth Games pole vaulter and decathlete

- Winifred Carney, suffragist and Irish independence activist

- Bryn Cunningham, Ulster Rugby player who attended Bangor Grammar School

- Kieron Dawson, Ulster Rugby player who attended Bangor Grammar School

- David Feherty, Professional golfer and now broadcaster, attended Bangor Grammar School

- Kelly Gallagher, MBE, British Winter Paralympic gold medallist

- Cherie Gardiner, former Miss Northern Ireland winner

- Keith Gillespie, N Ireland footballer, attended Rathmore Primary and Bangor Grammar School

- Billy Hamilton, former Northern Ireland international footballer

- Frederick Temple Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, diplomat and third Governor General of Canada

- Eddie Izzard, comedian (grew up in Bangor until age five)

- Alan Kernaghan, ex-Republic of Ireland and Middlesbrough FC professional footballer

- Bobby Kildea, musician (bassist and guitarist)

- Gary Lightbody, member of the band Snow Patrol

- Alex Lightbody, Former Northern Ireland, Irish and British Open Singles Champion Bangor Bowling Club

- Josh Magennis, professional footballer (Charlton Athletic; the Northern Irish National team)

- Stephen Martin, Olympic hockey gold medalist

- Mark McCall, Ulster rugby coach

- Mark McClelland, member of the band Snow Patrol

- Miles McMullan, aka Niall, author and naturalist

- William McWheeney, soldier; recipient of the Victoria Cross

- George McWhirter, author; winner with Chinua Achebe of the Commonwealth Poetry Prize inaugural Poet Laureate of Vancouver, Canada, former teacher at Bangor Grammar School

- Peter Millar, author; award-winning Sunday Times journalist

- Dick Milliken, Irish rugby and British Lion player attended Bangor Grammar School

- David Montgomery, media mogul

- Jamie Mulgrew, Northern Irish footballer (Linfield F.C.)

- Terry Neill, Arsenal F.C. captain (1962–63)

- W. P. Nicholson, Presbyterian preacher

- Lembit Öpik, former Liberal Democrat MP and Shadow Welsh and Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary

- Jonny Quinn, musician (Snow Patrol)

- Gillian Revie, former first soloist of the Royal Ballet

- Glenn Ross, strongman, multiple Britain's Strongest Man & UK's Strongest Man Champion

- Zöe Salmon, Blue Peter presenter; former Miss Northern Ireland

- Ian Sansom, author

- Mark Simpson, BBC Ireland Correspondent

- Patrick Taylor, author

- David Trimble, Nobel Laureate, former Ulster Unionist Party leader and former First Minister of Northern Ireland

- Samuel Cleland Davidson, inventor and engineer

- Paul Tweed, media lawyer

- Foy Vance, singer-songwriter

Twin towns – sister cities

Bangor is twinned with:[61][62]

- Bregenz, Austria

- Virginia Beach, United States

See also

- Bangor (civil parish)

- List of localities in Northern Ireland by population

- List of RNLI stations

- Market Houses in Northern Ireland

- Kilcooley estate

Notes

- On 20 May 2022, it was announced that as part of the Platinum Jubilee Civic Honours, Bangor would receive city status by Letters Patent later in 2022.[1]

References

- "Record number of city status winners announced to celebrate Platinum Jubilee". GOV.UK. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- A Wurd o Walcome Archived 25 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Blackbird Festival. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- "Record number of city status winners announced to celebrate Platinum Jubilee". GOV.UK. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- Pointon, GE (1990). BBC Pronouncing Dictionary of British Names (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-19-282745-6.

- "Beannchar/Bangor". Logainm.ie. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- "Census 2011 Population Statistics for Bangor Settlement". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Bangor Marina". Blue Flag Programme. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- "Platinum Jubilee: Eight towns to be made cities for Platinum Jubilee". BBC News. 19 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- Canon James Hamilton M.A. (1958). Bangor Abbey Through Fifteen Centuries. Bangor: Friends of Bangor Abbey. ISBN 0-9511562-3-3.

- p. 457, Hogan, Edmund, Onamasticon Goedelicum, Williams & Norgate, 1910, reprinted, Four Courts, 2000, ISBN 1-85182-126-0

-

Edward d'Alton (1907). "Bangor Abbey". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

Edward d'Alton (1907). "Bangor Abbey". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 30 April 2010. - "Bangor Civic Week". Bangor Town Council. 1951. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "Census 2001 Usually Resident Population: KS01 (Settlements) - Table view". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). p. 2. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "HISTPOP.ORG - Home". www.histpop.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016.

- 1813 estimate from Mason's Statistical Survey

- For a discussion on the accuracy of pre-famine census returns see JJ Lee “On the accuracy of the pre-famine Irish censuses Irish Population, Economy and Society edited by JM Goldstrom and LA Clarkson (1981) p54, in and also New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700-1850 by Joel Mokyr and Cormac Ó Gráda in The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 37, No. 4 (November 1984), pp. 473-88

- "NI Assembly: Key Statistics for Settlements, Census 2011 NIAR 404-15" (PDF). www.niassembly.gov.uk. 1 October 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ""Designed establishment in delightful country": planting, a plantation, The Plantation" (PDF). Lancaster University as part of a conference entitled 'Scotland and the 400th anniversary of the Plantation of Ulster: Plantations in Context'. 2010. p. 5.

- "Eclesia Bennchuir fundata est". University College Cork. Archived from the original on 30 June 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- "Bangor Cathedral". Medieval Heritage. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Lawlor, H.J. (1920). St. Bernard of Clairvaux's Life of St. Malachy of Armagh. London: The Macmillan Company. p. 25.

- Skene, William Forbes (1877). Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban. II ·. Vol. 2. Edmonston & Douglas. p. 55.

- Harper, Sally (2017). Music in Welsh Culture Before 1650: A Study of the Principal Sources. Taylor & Francis. p. 185. ISBN 9781351557269.

- Hamilton, Rector of Bangor Abbey

- Ua Clerigh, Arthur. "Antiphonary of Bangor." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 14 April 2015

- Edmonds, Columba (1908). "St. Columbanus". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- Hanna, John (2003). Old Bangor. Catrine, Ayrshire: Stenlake Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 9781840332414. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015.

- "The Tower House 34 Quay Street Bangor Co Down (HB 23/05/012)". Department for Communities. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "The Woman Who Took On King Billy, And Won". Historical Belfast. 7 October 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Millsopp, Sandra (14 November 2019). "Bangor's cotton mills; the Chambers Motor Company". Bangor Historical Society. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "Newtownards Walking Leaflet" (PDF). Ards and North Down Borough Council. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "1798 'summer soldiers recalled'". The Irish News. 26 July 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- <"Ward Park". Discover Northern Ireland. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "Pickie Fun Park, Bangor | Felix O'hare & Co Ltd". felixohare.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Granddaughter of Ike Eisenhower leads Bangor celebrations". Belfast Telegraph. 5 July 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "Northern Ireland Facts and Figures". In Your Pocket. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "2007: Springhill shopping centre, Carnlea, Bangor, Down". Excavations.ie. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Scott, Sarah (31 July 2019). "Council issues statement over future development of Bangor's Flagship". belfastlive. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "CEEQUAL | Awards | Balloo Waste Transfer Station and Recycling Centre, Bangor". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "Platinum Jubilee: Eight towns to be made cities for Platinum Jubilee". BBC News. 19 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- Malcolm Sutton: An Index of Deaths from the conflict in Ireland, Cain.ulst.ac.uk; accessed 9 February 2016.

- Sheehy, Kevin. More Questions Than Answers: Reflections on a life in the RUC, G&M, September 2008, p. 20; ISBN 978-0-7171-4396-2

- "UK NORTHERN IRELAND CONFLICT | AP Archive". www.aparchive.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- "UK NORTHERN IRELAND CONFLICT | AP Archive". www.aparchive.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- "CAIN: Chronology of the Conflict 1992". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- "CAIN: Peter Heathwood Collection of Television Programmes - Search Page". cain.ulst.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- "No warning for IRA car bomb: Four police officers seriously injured by second terrorist blast in seaside town in six months". The Independent. 8 March 1993. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "Bangor Castle". Bangor Historical Society. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- "Urban centres database 2018 visualisation - European Commission". Global Human Settlement. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- "Ballyholme Beach and Park". Visit Ards and North Down. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Ballyholme". Townlands of Ulster. 26 June 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- Sikora, Maeve. "Ballyholme". Vikingeskibsmuseet i Roskilde. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- Burke, Jason (27 November 2018). "The Woman Who Took On King Billy, And Won". Mysite. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Regional mapped climate averages". Met Office. November 2008. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Belfast and County Down Railway". Irish Railwayana. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- "Bangor stations" (PDF). Railscot - Irish Railways. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2007.

- "History". Bangor F. C. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- "Bangor Aurora Aquatic and Leisure Complex". Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Snow Patrol response to Ward Park gig". Snow Patrol Official Website. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- "Bangor Abbey, the European Connection". friendsofcolumbanusbangor.co.uk. Friends of Columbanus, Bangor. Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Bangor". vbsca.org. Sister Cities Association of Virginia Beach. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 316.