Battle of Red Cliffs

The Battle of Red Cliffs, also known as the Battle of Chibi, was a decisive naval battle in the winter of AD 208–209 at the end of the Han dynasty, about twelve years prior to the beginning of the Three Kingdoms period in Chinese history.[lower-alpha 2] The battle was fought between the allied forces of the southern warlords Sun Quan, Liu Bei, and Liu Qi against the numerically-superior forces of the northern warlord Cao Cao. Liu Bei and Sun Quan frustrated Cao Cao's effort to conquer the land south of the Yangtze River and reunite the territory of the Eastern Han dynasty.

| Battle of Red Cliffs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the wars at the end of the Han dynasty | |||||||||

Engravings on a cliff-side mark one widely accepted site of Chibi, near modern Chibi City, Hubei. The engravings are at least 1000 years old. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Sun Quan Liu Bei Liu Qi[1] | Cao Cao | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Zhou Yu Cheng Pu Liu Bei Liu Qi | Cao Cao | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 50,000[lower-alpha 1] |

800,000 (Cao Cao's claim)[lower-alpha 1] 220,000–240,000 (Zhou Yu's estimate)[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Heavy | ||||||||

| Battle of Red Cliffs | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 赤壁之戰 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赤壁之战 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The allied victory at Red Cliffs ensured the survival of Liu Bei and Sun Quan, gave them control of the Yangtze, and provided a line of defence that was the basis for the later creation of the two southern states of Shu Han and Eastern Wu.[3] According to Norwich University, this was the largest naval battle in history in terms of the numbers involved.[lower-alpha 3] Descriptions of the battle differ widely and the site of the battle is fiercely debated.[4] Although its location remains uncertain, most academic conjectures place it on the south bank of the Yangtze River, southwest of present-day Wuhan and northeast of Baqiu (present-day Yueyang, Hunan).

Background

By the early 3rd century, the Han dynasty, which had ruled China for almost four centuries (albeit with a 16-year interruption, which divided the dynasty into its Western and Eastern periods), was crumbling. Emperor Xian had been a political figurehead since 189, with no control over the actions of the various warlords controlling their respective territories. One of the most powerful warlords in China was Cao Cao, who by 207 had unified northern China and retained total control of the North China Plain. He then completed a successful campaign against the Wuhuan in the winter of the same year and thus secured his northern frontier. Upon his return in 208, he was appointed Chancellor, a position that granted him absolute authority over the entire imperial government.[5] Shortly afterwards, in the autumn of 208, his army began a southern campaign.[6][7]

The Yangtze River in the area of Jing Province was key to his strategy's success. If Cao Cao was to have any hope of reuniting the sundered empire, he had to achieve naval control of the middle Yangtze and to command the strategic naval base at Jiangling to get access to the southern region.[7] Two warlords controlled the regions of the Yangtze that were key to Cao Cao's success: Liu Biao, the governor of Jing Province, controlled the area west of the mouth of the Han River, which roughly encompassed the area around the city of Xiakou and all territory south of that region, and Sun Quan controlled the river east of the Han and the southeastern territories abutting it.[8] A third ally, Liu Bei, had fled with Liu Biao to the garrison in Fancheng from the northeast to Jing Province after a failed plot to assassinate Cao Cao and to restore power to the imperial dynasty.[9][10]

The initial stages of the campaign were an unqualified success for Cao Cao, as the command of Jing Province had been substantially weakened, and the Jing armies had been exhausted by conflict with Sun Quan to the south.[11] Factions had arisen to support either of Liu Biao's two sons in a struggle for succession. The younger son prevailed, and Liu Biao's dispossessed eldest son, Liu Qi, departed to assume a commandery, Jiangxia.[12] Liu Biao died of illness only a few weeks later, and Cao Cao was advancing from the north. Under those circumstances, Liu Biao's younger son and successor, Liu Cong, quickly surrendered. Cao Cao thus captured a sizeable fleet and secured the naval base at Jiangling, which provided him with a key strategic military depot and forward base to harbour his ships.[13]

When Jing Province fell, Liu Bei quickly fled south and was accompanied by a refugee population of civilians and soldiers. That disorganised exodus was pursued by Cao Cao's elite cavalry and was surrounded and decisively beaten at the Battle of Changban. Liu Bei escaped, however, and fled east to Xiakou, where he liaised with Sun Quan's emissary Lu Su. Historical accounts are then inconsistent; Lu Su may have successfully encouraged Liu Bei to move even more to the east, to Fankou (樊口, around present-day Ezhou, Hubei).[lower-alpha 4] In either case, Liu Bei was later joined by Liu Qi and levies from Jiangxia.[15] Liu Bei's main advisor, Zhuge Liang, was sent to Chaisang (柴桑; in present-day Jiujiang, Jiangxi) to negotiate forming a joint front against Cao Cao with Sun Quan.[16] In his talks with Sun Quan, Zhuge Liang claimed that Liu Bei's force was about 10,000 strong, while Liu Qi also fielded 10,000 men. These numbers might have been exaggerated, but the two had still organized a large force, albeit one which had still no chance against Cao Cao in an open battle.[17]

When Zhuge Liang arrived, Cao Cao had sent Sun Quan a letter boasting of commanding 800,000 men and hinting that he wanted Sun to surrender.[lower-alpha 5] The faction led by Sun Quan's Chief Clerk, Zhang Zhao, advocated surrender by citing Cao Cao's overwhelming numerical advantage. However, on separate occasions, Lu Su, Zhuge Liang, and Sun Quan's chief commander, Zhou Yu, all presented arguments to persuade Sun Quan to agree to the alliance against the northerners. Sun Quan finally decided upon war by chopping off a corner of his desk during an assembly and stating, "Anyone who still dares argue for surrender will be [treated] the same as this desk."[lower-alpha 6] He then assigned Zhou Yu, Cheng Pu, and Lu Su with 30,000 men to aid Liu Bei against Cao Cao.[18]

Although Cao Cao had boasted command of 800,000 men, Zhou Yu estimated Cao Cao's actual troop strength to be closer to 230,000. Furthermore, that total included 80,000 impressed troops from the armies of the recently-deceased Liu Biao and so the loyalty and morale of a large number of Cao Cao's force was uncertain.[19] With the 20,000 soldiers that Liu Bei had gathered, the alliance had approximately 50,000 marines who were trained and prepared for battle.[20]

Battle

The Battle of Red Cliffs unfolded in three stages: an initial skirmish at Red Cliffs followed by a retreat to the Wulin (烏林) battlefields on the northwestern bank of the Yangtze, a decisive naval engagement, and Cao Cao's disastrous retreat along Huarong Road.

The combined Sun-Liu force sailed upstream from either Xiakou or Fankou to Red Cliffs, where they encountered Cao Cao's vanguard force. Plagued by disease and low morale because of the series of forced marches that they had undertaken on the prolonged southern campaign,[7] Cao Cao's men could not gain an advantage in the small skirmish which ensued and so he retreated to Wulin, north of the Yangtze River, and the allies pulled back to the south.[21]

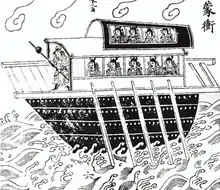

Cao Cao had chained his ships from stem to stern, possibly with the aim of reducing seasickness in his navy, which was composed mostly of northerners who were not used to living on ships. Observing that, the divisional commander Huang Gai sent Cao Cao a letter feigning surrender and prepared a squadron[lower-alpha 7] of capital ships described as mengchong doujian (蒙衝鬥艦).[lower-alpha 8] The ships had been converted into fire ships by filling them with bundles of kindling, dry reeds, and fatty oil. As Huang Gai's "defecting" squadron approached the midpoint of the river, the sailors applied fire to the ships before they took to small boats. The unmanned fire ships, carried by the southeastern wind, sped towards Cao Cao's fleet and set it ablaze. Many men and horses either burned to death or drowned.[26]

Following the initial shock, Zhou Yu and the allies led a lightly-armed force to capitalise on the assault. The northern army was thrown into confusion and utterly defeated. Seeing the situation was hopeless, Cao Cao then issued a general order of retreat and destroyed a number of his remaining ships before he withdrew.[27]

Cao Cao's army attempted a retreat along Huarong Road, including a long stretch passing through marshlands north of Dongting Lake. Heavy rains had made the road so treacherous that many of the sick soldiers had to carry bundles of grass on their backs and use them to fill the road to allow the horsemen to cross. Many of these soldiers drowned in the mud or were trampled to death in the effort. The allies, led by Zhou Yu and Liu Bei, gave chase over land and water until they reached Nan Commandery. Combined with famine and disease, that decimated Cao Cao's remaining forces. Cao Cao then retreated north to his home base of Ye and left Cao Ren and Xu Huang to guard Jiangling, Yue Jin stationed in Xiangyang, and Man Chong was in Dangyang.[27]

The allied counterattack might have vanquished Cao Cao and his forces entirely. However, the crossing of the Yangtze River had dissolved into chaos as the allied armies converged on the riverbank and fought over the limited number of ferries. To restore order, a detachment led by Sun Quan's general Gan Ning established a bridgehead in Yiling to the north, and only a staunch rearguard action by Cao Ren prevented a further catastrophe.[19][28]

Analysis

A combination of Cao Cao's strategic errors and the effectiveness of Huang Gai's ruse had resulted in the allied victory at the Battle of Red Cliffs. Zhou Yu had observed that Cao Cao's generals and soldiers were mostly cavalry and infantry, and few had any experience in naval warfare. Cao Cao also had little support among the people of Jing Province and so lacked a secure forward base of operations.[19] Despite the strategic acumen that Cao Cao had displayed in earlier campaigns and battles, he had simply assumed in this case that numerical superiority would eventually defeat the Sun and Liu navy. Cao's first tactical mistake was converting his massive army of infantry and cavalry into a marine corps and navy. With only a few days of drills before the battle, Cao Cao's troops were ravaged by sea-sickness and lack of experience on water. Tropical diseases to which the southerners were largely immune were also rampant in Cao Cao's camps. Although numerous, Cao Cao's men were already exhausted by the unfamiliar environment and the extended southern campaign, as Zhuge Liang observed: "Even a powerful arrow at the end of its flight cannot penetrate a silk cloth."[29]

A key advisor, Jia Xu, had recommended after the surrender of Liu Cong for the overtaxed armies to be given time to rest and to replenish before they engaged the armies of Sun Quan and Liu Bei, but Cao Cao disregarded that advice.[19] Cao Cao's own thoughts regarding his failure at Red Cliffs suggest that he held his own actions and misfortunes responsible for the defeat, rather than the strategies utilized by his enemy during the battle: "it was only because of the sickness that I burnt my ships and retreated. It is out of all reason for Zhou Yu to take the credit for himself."[30]

Aftermath

By the end of 209, the post that Cao Cao had established at Jiangling fell to Zhou Yu. The borders of the land under Cao Cao's control contracted about 160 kilometres (99 mi), to the area around Xiangyang.[31] For the victors of the battle, however, the question arose on how to share the spoils. Initially, Liu Bei and Liu Qi both expected rewards, having participated to the success at Red Cliffs, and both had also become entrenched in Jing Province.[32] Liu Qi was appointed Inspector of Jing Province, but his rule in the region, centered at Jiangxia Commandery, was short-lived. A few months after the Battle of Red Cliffs, he died of sickness. His lands were mostly absorbed by Sun Quan.[32] However, with Liu Qi dead, Liu Bei laid claim to the title of Inspector of Jing Province and began to occupy much of it.[32] He gained control of the four commanderies (Wuling, Changsha, Lingling, and Guiyang) south of the Yangtze River. Sun Quan's troops had suffered far greater casualties than Liu Bei's in the extended conflict against Cao Ren following the Battle of Red Cliffs, and the death of Zhou Yu in 210 resulted in a drastic weakening of Sun Quan's strength in Jing Province.[33]

As Liu Bei occupied Jing Province, which Cao Cao had recently lost, he gained a strategic and naturally-fortified area on the Yangtze River that Sun Quan still intended for himself. The control of Jing Province provided Liu Bei with virtually-unlimited access to the passage into Yi Province and important waterways into Wu (southeastern China) and dominion of the southern Yangtze River. Never again would Cao Cao command so large a fleet as he did at Jiangling, and he never had another similar opportunity to destroy his southern rivals.[34] The Battle of Red Cliffs and the capture of Jing Province by Liu Bei confirmed the separation of southern China from the northern heartland of the Yellow River valley and foreshadowed a north-south axis of hostility that would continue for centuries.[35]

Location

The precise location of the Red Cliffs battlefield has long been the subject of both popular and academic debates, but it has never been conclusively established.[lower-alpha 9] Scholarly debates have continued for at least 1350 years,[36] and a number of arguments in favour of alternative sites have been put forward. There are clear grounds for rejecting at least some of these proposals, but four alternative locations are still advocated. According to Zhang, many of the current debates stem from the fact that the course and length of the Yangtze River between Wuli and Wuhan has changed since the Sui and Tang dynasties.[37] The modern debate is also complicated by the fact that the names of some of the key locations have changed over the following centuries. For example, modern Huarong city is located in Hunan, south of the Yangtze, but in the 3rd century, the city of that name was due east of Jiangling, considerably north of the Yangtze.[38][4] Moreover, one of the sites, Puqi (蒲圻), was renamed "Chibi City" (赤壁市) in 1998 in a direct attempt to tie the location to the historical battlefield.[lower-alpha 10]

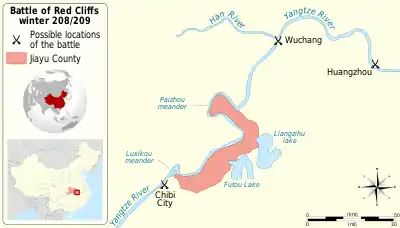

Historical records state that Cao Cao's forces retreated north across the Yangtze after the initial engagement at Red Cliffs, which unequivocally places the battle site on the south bank of the Yangtze. For this reason, a number of sites on the north bank have been discounted by historians and geographers. Historical accounts also establish eastern and western boundaries for a stretch of the Yangtze that encompasses all of the possible sites for the battlefield. The allied forces traveled upstream from either Fankou or Xiakou. Since the Yangtze flows roughly eastward towards the ocean (with northeast and southeast meanders), Red Cliffs must at least be west of Fankou, which is farther downstream. The westernmost boundary is also clear since Cao Cao's eastern advance from Jiangling included passing Baqiu (present-day Yueyang, Hunan) on the shore of Dongting Lake. The battle must also have been downstream (northeast) of that place.[39][40]

One popular candidate for the battle site is Chibi Hill in Huangzhou, sometimes referred to as "Su Dongpo's Red Cliffs" or the "Literary Red Cliffs" (文赤壁). This conjecture arises largely from the famous 11th-century poem "First Rhapsody on the Red Cliffs", which equates the Huangzhou Hill with the battlefield location. Excluding tone marks, the contemporary Mandarin pinyin romanization of the cliff's name is "Chibi", the same as the pinyin for Red Cliffs. However, the Chinese characters are completely different (赤鼻), as is their meaning ("Red Nose Hill"), and the contemporaneous pronunciation of the words are also different, which is reflected by their distinct pronunciations in many non-Mandarin dialects. Consequently, virtually all scholars have dismissed the connection. The site is also on the north bank of the Yangtze and is directly across from Fankou, rather than upstream from it.[36] Moreover, if the allied Sun-Liu forces left from Xiakou rather than Fankou, as the oldest historical sources suggest,[lower-alpha 4] the hill in Huangzhou would have been downstream from the point of departure, a possibility that cannot be reconciled with historical sources.

Puqi, now called Chibi City, is perhaps the most widely accepted candidate. To differentiate from Su Dongpo's Red Cliffs, the site is also referred to as the "Military Red Cliffs" (武赤壁). It is directly across the Yangtze from Wulin. That argument was first proposed in the early Tang dynasty.[40] There are also characters engraved in the cliffs (see image at the top of this page), which suggested that was the site of the battle. The origin of the engraving can be dated to between the Tang and Song dynasties, which makes it at least 1,000 years old.[41]

Some sources mention the south banks of the Yangtze in Jiayu County (嘉鱼县) in the prefecture-level city of Xianning in Hubei province as a possible location. That would place the battlefield downstream from Puqi (Chibi City), a view that is supported by scholars of Chinese history such as de Crespigny, Wang Li, and Zhu Dongrun, who follow the Qing dynasty historical document Shui Jing Zhu.[42]

Another candidate is Wuhan, which straddles the Yangtze at the confluence of the Yangtze and Han rivers. It is east of both Wulin (and Chibi City across the river) and Jiayu. The metropolis was incorporated by joining three cities. There is a local belief in Wuhan that the battle was fought at the junction of the rivers, southwest of the former Wuchang city, which is now part of Wuhan.[43] Zhang asserts that the Chibi battlefield was one of a set of hills in Wuchang levelled in the 1930s so that their stone could be used as raw material.[44][lower-alpha 11] Citing several historical-geographical studies, Zhang shows that earlier accounts place the battlefield in Wuchang.[46] Sheng Hongzhi's 5th-century Jingzhou ji in particular places the Chibi battlefield a distance of 160 li (approximately 80 kilometres (50 mi)) downstream from Wulin, but since the Paizhou and Luxikou meanders increased the length of the Yangtze River between Wuli and Wuchang by 100 li (approximately 50 kilometres (31 mi); see map) some time in the Sui and Tang dynasties,[37] later works do not regard Wuchang as a possible site.

Fictionalised account

The romantic tradition that originated with the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms differs from historical accounts in many details. For example, Cao Cao's army strength was exaggerated to over 830,000 men. That may be attributed to the ethos of later times, particularly of the Southern Song dynasty.[47] The state of Shu Han, in particular, was viewed by later literati as the "legitimate" successor to the Han dynasty and so fictionalised accounts assign greater prominence than is warranted by historical records to the roles of Liu Bei, Zhuge Liang and other heroes from Shu. That is generally accomplished by minimising the importance of Eastern Wu commanders and advisors such as Zhou Yu and Lu Su.[48] While historical accounts describe Lu Su as a sensible advisor and Zhou Yu as an eminent military leader and "generous, sensible and courageous" man, Romance of the Three Kingdoms depicts Lu Su as unremarkable and Zhou Yu as cruel and cynical.[49] Both are depicted as being inferior to Zhuge Liang in every respect.[2]

The romances added wholly fictional and fantastical elements to the historical accounts, and these were repeated in popular plays and operas. Examples from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms include Zhuge Liang pretending to use magic to call forth favourable winds for the fire ship attack, his strategy of "using straw boats to borrow arrows", and Guan Yu capturing and releasing Cao Cao at Huarong Trail. The fictionalised accounts also name Zhuge Liang as a military commander in the combined forces, which is historically inaccurate.[50]

Cultural impact

The modern Chibi City, in Hubei Province, used to be called Puqi. In 1998, the Chinese State Council approved the renaming of the city in celebration of the battle at Red Cliffs. Cultural festivals held by the city have dramatically increased tourism.[51] In 1983, a statue of prominent Song dynasty poet, Su Shi, was erected at the Huangzhou site of 'lasu Dongpo's Red Cliffs in tribute to his writings regarding Red Cliff.[52]

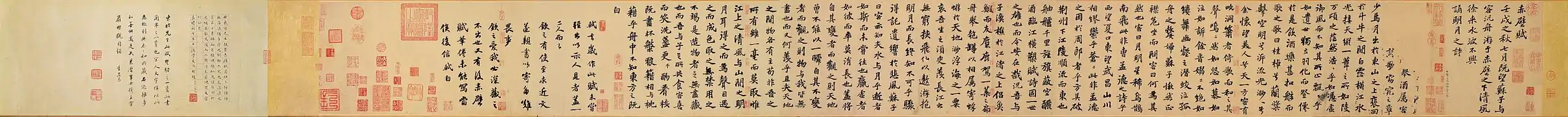

Former Ode on the Red Cliffs, A famous poem by Su Shi written during the Song dynasty – National Palace Museum

Former Ode on the Red Cliffs, A famous poem by Su Shi written during the Song dynasty – National Palace Museum

Video games based on the Three Kingdoms era (such as Koei's Dynasty Warriors series, Sangokushi Koumeiden, Warriors Orochi series, Destiny of an Emperor, Kessen II and Total War: Three Kingdoms) have scenarios that include the battle. Other games use the Battle of Red Cliffs as their central focus with titles popular in Asia, such as the original Japanese version of Warriors of Fate and Dragon Throne: Battle of Red Cliffs.

A 2008 film, Red Cliff,[lower-alpha 12] was directed by John Woo, showcased the Red Cliff legacy, and was a massive box office success.

Notes

- See Red Cliffs order of battle for the sources.

- "The engagement at the Red Cliffs took place in the winter of the 13th year of Jian'an, probably about the end of 208."[2]

- "The Largest Naval Sea Battles in Military History". norwich.edu. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- Chen Shou's Records of the Three Kingdoms repeatedly asserts that Liu Bei was at Xiakou. Other historical accounts support that version as well. Annotations to the text of the Records of the Three Kingdoms made nearly two centuries later by Pei Songzhi support the Fankou version in which Xiakou appears in the main text and Fankou in the annotations. That discrepancy is later reflected in contradictory passages in the Zizhi Tongjian by Sima Guang (and its English translation[14]), which has Liu Bei "quartered at Fankou" at the same time as Zhou Yu is requesting to send troops to Xiakou, and Liu Bei "waits anxiously" in Xiakou for the reinforcements. For a detailed discussion, see Zhang (2006, pp. 231–34)

- (江表傳載曹公與權書曰:「近者奉辭伐罪,旄麾南指,劉琮束手。今治水軍八十萬衆,方與將軍會獵於吳。」權得書以示羣臣,莫不嚮震失色。) Jiang Biao Zhuan annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 47.

- (江表傳曰:權拔刀斫前奏案曰:「諸將吏敢復有言當迎操者,與此案同!」) Jiang Biao Zhuan annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 54.

- The number of vessels in the squadron is unclear. As de Crespigny observes, "Firstly, the Records of the Three Kingdoms states that the number of vessels in Huang Gai's squadron was 'several tens,' but the parallel passage in Zizhi Tongjian... allocates Huang Gai only ten ships".[22]

- The exact nature of the vessels is unclear. Xiugui Zhang refers to them as "leather-covered assault warships", but the reference is parenthetical, as that issue is peripheral to the topic of Zhang's paper.[23] In a lengthier discussion, Rafe de Crespigny[24] separates the two terms, describing mengchong as "... covered with some form of protective material ... used to break the enemy line of battle and perhaps to damage their ships and men with a ram or by projectiles" and doujian as "... fighting platforms for spearmen and archers to engage in close combat ...".[25] He concludes that mengchong doujian is a "general description for vessels of war".[22]

- This discussion is largely drawn from Zhang (2006).

- See http://www.chibi.com.cn Archived 2007-07-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- C. P. Fitzgerald described the location in 1926: "But there was the ... two rivers, the Han and the ... Yangtze, across them, respectively, Hanyang and Wuchang ... The confluence of the Han ... and the Yangtze ... made Wuhan ... a key strategic centre. Hanyang is backed by a long, low hill, called Tortoise Mountain, which faces the hill on the eastern slope of which Wuchang is built. The two hills narrow the Yangtze at this point by perhaps as much as a third of its width above and below them. The passage is dominated by a high bluff, called Chi Bi, "The Red Cliff", the scene of a famous naval battle in the fourth [sic] century. It is at this point that the great bridge, carrying railway and road, has been constructed in the fledgling years of the People's Republic of China [45]

- "The Battle of Red Cliff (Chi Bi) – MonkeyPeaches". Archived from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

References

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 538.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 264.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 273.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 256 78n.

- de Crespigny 1969, pp. 253, 465 6n.

- Eikenberry 1994.

- de Crespigny 2003.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 773.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 480.

- de Crespigny 1969, p. 258.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 486.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 241.

- de Crespigny 1990, pp. 246, 250, 255.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 248.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 255.

- de Crespigny 1969, p. 263.

- de Crespigny 2018, p. 205.

- de Crespigny 1996.

- Eikenberry 1994, p. 60.

- de Crespigny 1990, pp. 252, 255.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 257.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 265.

- Zhang 2006, p. 218.

- de Crespigny 1990, pp. 266–268.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 268.

- Chen c. 280, pp. 54, 1262–1263.

- Chen c. 280.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 239.

- Military Documents 1979.

- Chen c. 280, p. 54:1265.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 291.

- de Crespigny 2018, p. 227.

- de Crespigny 1990, pp. 291–292, 197.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 37.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 260.

- Zhang 2006, p. 215.

- Zhang 2006, p. 225.

- Zhang 2006, p. 229.

- de Crespigny 1990, pp. 256–257.

- Zhang 2006, p. 217.

- Zhang 2006, pp. 219, 228.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 256.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. 256 n 78.

- Zhang 2006, pp. 215, 223.

- Fitzgerald 1985, pp. 90, 92–93.

- Zhang 2006.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 483.

- de Crespigny 1990, p. xi.

- de Crespigny 1990, pp. 300, 305–306 29n.

- de Crespigny 1990, pp. 260–264.

- Xinhua 1997.

- Xinhua 1983.

Sources

- "11th century writer's statue erected in Hubei province". Xinhua News Agency, January 19, 1983. Retrieved on July 22, 2007.

- "Ancient battlefield turns to tourism site". Xinhua News Agency, June 11, 1997. Retrieved on July 22, 2007.

- Chen, Shou (c. 280) [1959], Sanguo zhi (History of the Three Kingdoms) (Reprint ed.), Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004156050.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (1969), The Last of the Han: being the chronicle of the years 181–220 AD as recorded in chapters 58–68 of the Tzu-chih t'ung-chien of Ssu-ma Kuang, Canberra: Australian National University, Centre of Oriental Studies.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (1990), Generals of the South: The foundation and early history of the Three Kingdoms state of Wu, Canberra: Australian National University Internet Edition 2004.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2018) [1st pub. 1990]. Generals of the South: the foundation and early history of the Three Kingdoms state of Wu (Internet ed.). Acton, Australian Capital Territory: Australian National University.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (1996), To Establish Peace: being the Chronicle of the Later Han dynasty for the years 189 to 220 AD as recorded in Chapters 59 to 69 of the Zizhi Tongjian of Sima Guang, Canberra: Australian National University Internet Edition 2004.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2003), The Three Kingdoms and Western Jin A history of China in the Third Century AD Internet edition.

- Eikenberry, Karl W. (1994), "The campaigns of Cao Cao", Military Review, 74 (8): 56–64.

- Fitzgerald, C. P. (1985), Why China? Recollections of China 1923–1950, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Pei, Songzhi (429), Sanguozhi zhu.

- The Military Documents Research Organization of the Wuhan Military District (1979). Zhongguo Gudai Zhanzheng Yibaili (One Hundred Battles of Ancient Chinese History). Wuhan: Hubei Province People's Publishing House.

- Zhang, Xiugui (2006), "Ancient "Red Cliff" battlefield: a historical-geographic study", Frontiers of History in China, 1 (2): 214–235, doi:10.1007/s11462-006-0003-3.