Khaleda Zia

Khaleda Zia (Bengali pronunciation: [kʰaled̪a dʒia]; born Khaleda Khanam Putul[1][2] in 1945) is a Bangladeshi politician who served as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh from 1991 to 1996, and again from 2001 to 2006.[3] She was the first female prime minister of Bangladesh. She was the wife of former President of Bangladesh Ziaur Rahman. She is the current chairperson and leader of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) which was founded by Rahman in 1978.

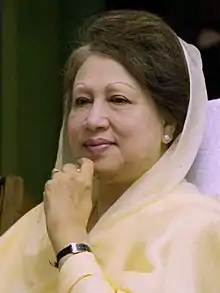

Khaleda Zia | |

|---|---|

খালেদা জিয়া | |

Zia in 2010 | |

| Prime Minister of Bangladesh | |

| In office 10 October 2001 – 29 October 2006 | |

| President |

|

| Preceded by | Latifur Rahman (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Iajuddin Ahmed (Acting) |

| In office 20 March 1991 – 30 March 1996 | |

| President |

|

| Preceded by | Kazi Zafar Ahmed |

| Succeeded by | Muhammad Habibur Rahman (Acting) |

| Chairperson of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party | |

Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 10 May 1984 | |

| General Secretary | A. Q. M. Badruddoza Chowdhury Abdus Salam Talukder Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan Khandaker Delwar Hossain Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir |

| Preceded by | Abdus Sattar |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 29 December 2008 – 9 January 2014 | |

| Prime Minister | Sheikh Hasina |

| Preceded by | Sheikh Hasina |

| Succeeded by | Rowshan Ershad |

| In office 23 June 1996 – 15 July 2001 | |

| Prime Minister | Sheikh Hasina |

| Preceded by | Sheikh Hasina |

| Succeeded by | Sheikh Hasina |

| Member of Parliament | |

| In office 20 March 1991 – 15 July 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Zafar Imam |

| Succeeded by | Sayeed Iskander |

| Constituency | Feni-1 |

| In office 29 December 2008 – 9 January 2014 | |

| Preceded by | Sayeed Iskander |

| Succeeded by | Shirin Akhter |

| Constituency | Feni-1 |

| In office 1 October 2001 – 29 October 2006 | |

| Preceded by | Zafar Imam |

| Succeeded by | Muhammad Jamiruddin Sircar |

| Constituency | Bogra-6 |

| First Lady of Bangladesh | |

| In role 21 April 1977 – 30 May 1981 | |

| President | Ziaur Rahman |

| Preceded by | Sheikh Fazilatunnesa Mujib |

| Succeeded by | Rowshan Ershad |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Khaleda Khanam Putul 1945 (age 76-77) See Birth date discrepancy Jalpaiguri, Bengal Presidency, British India (present-day West Bengal, India) |

| Political party | Bangladesh Nationalist Party (1979–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse | Ziaur Rahman (m. 1960–1981) |

| Relations |

|

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Majumdar-Zia family |

After a military coup in 1982, led by Army Chief General Hussain Muhammad Ershad, Zia helped lead the movement for democracy until the fall of Ershad in 1990. She became the prime minister following the BNP party win in the 1991 general election. She also served briefly in the short-lived government in 1996, when other parties had boycotted the first election. In the next round of general elections of 1996, the Awami League came to power. Her party came to power again in 2001. She has been elected to five separate parliamentary constituencies in the general elections of 1991, 1996 and 2001.

She developed a reputation as the "Uncompromising leader" due to her staunch opposition against military dictatorship of Ershad in the 1980s and her commitment to restore democracy in Bangladesh. She was put under house arrest several times by Ershad government, and later by Sheikh Hasina led government.[4] She was honored as “Fighter for Democracy” by the New Jersey’s State Senate in 2011.[5]

In its list of the 100 Most Powerful Women in the World, Forbes magazine ranked Zia at number 14 in 2004,[6] number 29 in 2005,[7] and number 33 in 2006.[8]

Following her government's term end in 2006, the scheduled January 2007 elections were delayed due to political violence and in-fighting, resulting in a bloodless military takeover of the caretaker government. During its interim rule, it charged Zia and her two sons with corruption.[9][10][11]

Since the 1980s, Zia's chief rival has been Awami League leader Sheikh Hasina. Since 1991, they have been the only two serving as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh.[12]

Zia was jailed for a total of 17 years for the Zia Orphanage Trust corruption case and Zia Charitable Trust corruption case in 2018. A local court handed her the verdict for abusing power as the prime minister while disbursing a fund in favor of newly formed Zia Orphanage Trust.[13] Referring to the international and domestic legal experts, the U.S. State Department in its 2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices opined that “lack of evidence to support the conviction” suggests the case was a political ploy to remove her from the electoral process.[14] Amnesty International raised concerns that her “fair trial rights are not respected.”[15]

Zia was transferred to a hospital for medical treatment in April 2019.[16] In March 2020, she was released for six months on humanitarian grounds with the conditions that she would stay at her home in Gulshan, Dhaka and not travel abroad.[17] The 6-month period suspension was granted for the fifth time in March 2022.[18]

Personal life and family

Early life and education

Khaleda Khanam "Putul"[19] was born in 1945 in Jalpaiguri in the then undivided Dinajpur District[note 1] in Bengal Presidency, British India (now in Jalpaiguri District, India).[3][20] She was the third of five children.[21] She was the daughter of tea-businessman Iskandar Ali Majumder, who was in turn the son of Salamat Ali Majumdar, who was the son of Azgar Ali Majumdar, who was the son of Nahar Muhammad Khan, who was the son of Murad Khan, a 16th-century Middle Eastern immigrant.[21][22] Her mother, Taiyaba Majumder, was from Chandbari (now in Uttar Dinajpur District).[23][21] After the partition of India in 1947, they migrated to Dinajpur town (now in Bangladesh).[3] Khanam first attended Dinajpur Missionary School and later completed her matriculation from Dinajpur Girls' School in 1960.[3] In the same year, she married Ziaur Rahman, then a captain in the Pakistan Army.[24] She then used the name "Khaleda Zia" or "Begum Khaleda Zia". Zia then studied at Dinajpur Surendranath College until 1965 when she went to West Pakistan to stay with her husband.[3] In March 1969, they moved from Karachi to Dhaka.[21] Following Rahman's posting, the family then moved to Sholoshohor area in Chittagong.[21] She was a prisoner at Dhaka Cantonment in 1971 at the time of Freedom Fight/Liberation War of Independence under custody of Pakistan Army's Major General Jamshed.

Family

Zia's first son, Tarique Rahman (b. 1967), got involved into politics and went on to become the acting chairman of Bangladesh Nationalist Party.[25] Her second son, Arafat Rahman "Koko" (b. 1969), died of a cardiac arrest in 2015.[26] Zia's sister, Khurshid Jahan (1939–2006) served as the Minister of Women and Children Affairs during 2001–2006.[27] Her younger brother, Sayeed Iskander (1953–2012), was also a politician who served as a Jatiya Sangsad member from the Feni-1 constituency during 2001–2006.[28] Her second brother, Shamim Iskandar, is a retired flight engineer of Bangladesh Biman.[29][30] Her second sister is Selina Islam.[31]

Involvement in politics

On 30 May 1981, Khaleda Zia's husband, the-then President of Bangladesh Ziaur Rahman, was assassinated.[32] After his death, on 2 January 1982, she got involved into politics by first becoming a member of Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) - the party which was founded by Rahman.[33] She took charge of the vice-chairman position in March 1983.[33]

Anti-Ershad Movement

In March 1982, the then chief of Bangladesh Army, Hussain Muhammad Ershad forced Bangladesh's President Justice Abdus Sattar to resign and become the Chief Martial Law Administrator (CMLA) of the country.[34] This marked the beginning of a nine-year-long military dictatorship in Bangladesh.

BNP and 7 party alliance

Begum Khaleda Zia, from the first day of Ershad's rule, protested the military dictatorship and had a very uncompromising stance.[35] She became the Senior Vice-President of BNP by May 1983. Under her active leadership, BNP started discussing the possibilities of a unified movement with six other parties on 12 August 1983 and formed a '7 party alliance' by the first week of September 1983.[3] BNP, led by Khaleda Zia also reached an action-based agreement with other political parties to launch a movement against Ershad.

On 30 September 1983, Begum Khaleda Zia led the first major public rally in front of the party office and was hailed by the party workers. On 28 November 1983, she took part in the "gherao movement" (encircling) of the Secretariat building at Dhaka along with the alliance leaders, which was quelled by Ershad's ruthless police force and she was put under house arrest on the same day.

Due to the deteriorating health conditions, Justice Abdus Sattar resigned from the position of BNP chief on 13 January 1984 and was replaced by Begum Khaleda Zia who was then the Senior Vice President of the party. In May 1984, she was elected as the Chairperson of the party in a council by the councilors.[36]

After assuming the position of party chief, Khaleda Zia spearheaded the movement against Ershad. In 1984, along with other parties, she declared 6 February as the 'Demand Day' and 14 February as 'Protest Day'. Country-wide rallies were organized on those days and activists of the movement died on the streets fighting the ruthless police force loyal to President Ershad.[37]

The 7-party alliance held a countrywide 'Mass Resistance Day' on 9 July 1984, In support of their demand for the immediate withdrawal of Martial Law, the opposition forces called the countrywide gherao and demonstrations from 16–20 September and a full day hartal on 27 September of 1984.[37]

The protests continued in 1985 as well and as a result, in March of the same year Ershad-led government tightened the grip of martial law and put Begum Khaleda Zia under house arrest.[38]

Boycotting 1986 election

To divert the political pressure, Lt. General Ershad declared a date for a fresh election in 1986. Initially, the two major opposition alliances, '7 party alliance' led by BNP and '15 party alliance' led by Awami League discussed the possibilities of participating in the election forming a greater election alliance to catch Ershad off the guard. But Awami League refused to form any election alliance and Sheikh Hasina in a public rally declared anyone who would join the election under Ershad would be a 'national traitors', on 19 March 1986.

However, Sheikh Hasina's Awami League, along with Communist Party of Bangladesh and six other parties, joined the election under Ershad, resulting in the split between the 15 party alliance, On the other hand, Begum Khaleda Zia uncompromisingly declared the election illegal and urged people to resist the election.

The government of Ershad put her under house arrest on the eve of the election while Awami League, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, Communist Party of Bangladesh and other smaller parties took part in the election only to lose to the Jatiya Party of Ershad.

Begum Khaleda Zia's uncompromising attitude and her defiance to the military dictatorship made an image of an "Uncompromising leader" in the eyes of people. Dr Gowher Rizvi in his analysis wrote:

The ability to stand up against governmental oppression, to boycott elections, to refuse offices of profit, or to suffer imprisonment are considered evidence of personal sacrifices something which is greatly admired by the people of a country where politics is generally an unabashed pursuit of power and personal aggrandizement. From the moment Khaleda was installed as the leader of the BNP, she has publicly remained opposed to participation in any election held while Ershad was in power. Her popularity soared after she boycotted the polls in 1986.[35]

Later in that year, on the eve of 1986 Bangladeshi presidential election, Khaleda Zia was put under house arrest once again.[39]

Fall of Ershad

Khaleda Zia was put under house arrest multiple times from 1986 to 1990 by Ershad's military government.

On 13 October 1986, she was put under house arrest right before the 1986 Bangladeshi presidential election and was released only after the election. She took the lead on her release and initiated a fresh movement with a view to deposing Ershad. She called a half-day strike on 10 November of the same year only to be put under house arrest again.[37]

On 24 January 1987, when Sheikh Hasina joined the parliament session with other Awami League leaders, Khaleda Zia was on the street demanding the dissolution of the parliament. She called for a mass rally in Dhaka which turned violent and top leaders of BNP were arrested. After that, a series of strikes were organized by 7 party alliance led by Khaleda Zia from February to July 1987. On 22 October of the year, Khaleda Zia's BNP in collaboration with Sheikh Hasina's Awami League declared "Dhaka Seize" programme on 10 November to overthrow Ershad.[37]

As a countermeasure, Ershad's government rounded up thousands of political leaders and activists, but on the day of seizing there were complete chaos on the streets and dozens died. The government of Ershad put Khaleda Zia under house arrest after detaining her from Purbani Hotel, from where she was coordinating the movement. On 11 December 1987, Khaleda was set free but she immediately held a press conference and claimed that she was "prepared to die" to depose the dictator.[40]

After the eventful 1987, two following years went relatively calm with sporadic violence. A fresh wave of movements started when BNP's student wing Chatra Dal started winning most of the student union elections across the country. By 1990, Chatra Dal took control of 270 out of 321 student unions of the country, riding on the popularity of Khaleda Zia. They also won all the posts of Dhaka University Central Students' Union in 1990.[35] The new committee of DUCSU led by Amanullah Aman declared fresh programmes to overthrow Ershad in line with BNP's programmes. On 10 October 1990, in a violent turn of events Chatra Dal leader Naziruddin Jehad died on the street of Dhaka that paved the way for a greater alliance between all the opposition forces.[41]

After two-month-long protests, BNP led by Begum Khaleda Zia, along with other political parties, compelled Ershad to offer his resignation on 4 December 1990.

Premiership

Begum Khaleda Zia served as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh for three times. Her first term was from March 1991 to February 1996, second term lasted for a few weeks after February 1996 and third term was from October 2001 to October 2006. She is particularly remembered for her role in making education accessible and introducing some key economic reforms.

First term

A neutral caretaker government in Bangladesh oversaw elections on 27 February 1991[42] following eight years of Ershad presidency. BNP won 140 seats - 11 short of simple majority.[42][43] Zia was sworn in as the country's first female prime minister on 20 March 1991 with the support of a majority of the deputies in parliament. With a unanimous vote, the parliament passed the 12th amendment to the constitution in August 1991. The acting president Shahabuddin Ahmed granted Zia nearly all of the powers that were vested in the president at the time, effectively returning Bangladesh to a parliamentary system in September.

Education reforms

When Begum Khaleda Zia took charge in 1991, Bangladeshi children's average schooling years was around two years and for every three boys there was one girl studying in the same classroom. Begum Khaleda Zia promoted education and vocational training very aggressively.[44] Her government made primary education free and mandatory for all. And for girls, the education was made free till 10th grade.[45]

To fund the implementation of new reforms and policies, in 1994 the allocation of budget in education sector was increased by 60% and received the highest allocation among other sectors.[46]

In 1990, only 31.73% students passed in the SSC examination and the rate was 30.11% for female. In 1995, thanks to her policies, 73.2% students passed the SSC examination and among the female students, 71.58% passed.[47]

Economic reforms

Some of the major economic reforms marked the first Khaleda Zia government that included the introduction of Value Added Tax (VAT), formulation of Bank Company Act in 1991 and Financial Institutions Act in 1993, and the establishment of privatization board in 1993.[48] Besides, Bangladesh signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1993.

A new export processing zone was established near Dhaka in 1993 to attract foreign investors.[49]

Administrative reforms

The first Khaleda Zia government, to address popular demand, passed a law to allow the mayors of city corporations to be elected directly by the voters. Before that the elected ward councilors of each ward of the city corporation used to elect the mayor of the city.[50]

Zia's administration abolished the Upazila system in November 1991. It formed the Local Government Structure Review Commission, which recommended a two-tier system of local government, district and union councils. Also the Thana Development and Coordination Committee was formed to coordinate development activities at the thana level.[51]

Second term

When the opposition boycotted the 15 February 1996 election, Zia's party BNP had a landslide victory in the 6th Jatiya Sangshad.[52] Other major parties demanded a neutral caretaker government to be appointed to oversee the elections. The short-lived parliament hastily introduced the caretaker government by passing the 13th amendment to the constitution. The parliament was dissolved to pave the way for parliamentary elections within 90 days.

In the 12 June 1996 elections, BNP lost to Sheikh Hasina's Awami League. Winning 116 seats,[52] BNP emerged as the largest opposition party in the country's parliamentary history.

Third term

The BNP formed a four-party alliance[53] on 6 January 1999 to increase its chances to return to power in the next general elections. These included its former political foe the Jatiya Party, founded by President Ershad after he led a military government, and the Islamic parties of Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh and the Islami Oikya Jot. It encouraged protests against the ruling Awami League.

Many residents strongly criticized Zia and BNP for allying with Jamaat-e-Islami,[54] which had opposed the independence of Bangladesh in 1971. The four-party alliance participated in the 1 October 2001 general elections, winning two-thirds of the seats in parliament and 46% of the vote (compared to the principal opposition party's 40%). Zia was sworn in as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh.

She worked on a 100-day programme to fulfill most of her election pledges to the nation. During this term, the share of domestic resources in economic development efforts grew. Bangladesh began to attract a higher level of international investment for development of the country's infrastructure, energy resources and businesses, including from the United States, Great Britain, and Japan. Restoration of law and order was an achievement during the period.

Zia promoted neighbourly relations in her foreign policy. In her "look-east policy," she worked to bolster regional cooperation in South Asia and adherence to the UN Charter of Human Rights. She negotiated settlement of international disputes, and renounced the use of force in international relations. Bangladesh began to participate in United Nations international peacekeeping efforts. In 2006, Forbes magazine featured her administration in a major story praising her achievements. Her government worked to educate young girls (nearly 70% of Bangladeshi women were illiterate) and distribute food to the poor (half of Bangladesh's 135 million people live below the poverty line). Her government promoted strong GDP growth (5%) based on economic reforms and support of an entrepreneurial culture.

When Zia became prime minister for the third time, the GDP growth rate of Bangladesh remained above 6 percent. The Bangladesh per capita national income rose to 482 dollars. Foreign exchange reserve of Bangladesh had crossed 3 billion dollars from the previous 1 billion dollars. The foreign direct investments of Bangladesh had risen to 2.5 billion dollars. The industrial sector of the GDP had exceeded 17 percent at the end of Zia's office.[3]

On 29 October 2006, Zia's term in office ended. In accordance with the constitution, a caretaker government would manage in the 90-day interim before general elections. On the eve of the last day, rioting broke out on the streets of central Dhaka due to uncertainty over who would become Chief Advisor (head of the Caretaker Government of Bangladesh). Under the constitution, the immediate past Chief Justice was to be appointed. But, Chief Justice Khondokar Mahmud Hasan (K M Hasan) declined the position.[55][56][57][58] President Iajuddin Ahmed, as provided for in the constitution, assumed power as Chief Advisor on 29 October 2006.[59] He tried to arrange elections and bring all political parties to the table during months of violence; 40 people were killed and hundreds injured in the first month after the government's resignation in November 2006.

Mukhlesur Rahman Chowdhury, the presidential advisor, met with Zia and Sheikh Hasina, and other political parties to try to resolve issues and schedule elections. Negotiations continued against a backdrop of political bickering, protests and polarisation that threatened the economy.[60][61] Officially on 26 December 2006, all political parties joined the planned 22 January 2007 elections. The Awami League pulled out at the last minute, and in January the military intervened to back the caretaker government for a longer interim period. It held power until holding general elections in December 2008.

Foreign policy

- Saudi Arabia: Zia made some high-profile foreign visits in the later part of 2012. Invited to Saudi Arabia in August by the royal family, she met with the Saudi crown prince and defence minister Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud to talk about bilateral ties.[62] She tried to promote better access for Bangladeshi migrant workers to the Saudi labour market, which was in decline at the time.[62]

- People's Republic of China: She went to People's Republic of China in October, at the invitation of the government. She met with Chinese leaders including Vice President Xi Jinping and the Communist Party of China's international affairs chief Wang Jiarui.[63] Xi became China's Paramount Leader in 2012.

Talks in China related to trade and prospective Chinese investment in Bangladesh,[64] particularly the issue of financing Padma Bridge. At the beginning of 2012, the World Bank, a major prospective financier, had withdrawn, accusing government ministers of graft.[63][65] The BNP announced that the Chinese funding for a second Padma Bridge was confirmed during her visit.[66][67]

- India: On 28 October 2012, Zia visited India to meet with President Pranab Mukherjee, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and a number of officials including foreign minister Salman Khurshid, national security adviser Shivshankar Menon, foreign secretary Ranjan Mathai and BJP leader and leader of opposition Sushma Swaraj. Talks were scheduled to cover bilateral trade and regional security.[68]

Zia's India visit was considered notable as BNP had been considered to have been anti-India compared to its rival Awami League.[69] At her meeting with Prime Minister Singh, Zia said her party wanted to work with India for mutual benefit, including the fight against extremism.[70] Indian officials announced they had come to agreement with her to pursue a common geopolitical doctrine in the greater region to discourage terrorists.[71]

Post-premiership (since 2007)

Detention during the caretaker government

Former Bangladesh Bank governor Fakhruddin Ahmed became the Chief Adviser to the interim caretaker government on 12 January 2007. In March, Zia's eldest son, Tarique Rahman, was arrested for corruption. Enforcing the suppression of political activity under the state of emergency, from 9 April, the government barred politicians from visiting Zia's residence.[72] Her other son, Arafat Rahman (Coco), was arrested for corruption on 16 April.[9] On 17 April, The Daily Star reported that Zia had agreed to go into exile with Arafat.[73] Her family said, the Saudi Arabian government reportedly declined to allow her into the kingdom - apparently because "it was reluctant to take in an unwilling guest".[74] Based on an appeal, on 22 April the High Court issued a ruling for the government to explain that she was not confined to her house. On 25 April, the government lifted restrictions on both Zia and Sheikh Hasina.[74] On 7 May, the High Court ordered the government to explain continuing restrictions on Zia.[75]

On 17 July, the Anti Corruption Commission Bangladesh (ACC) sent notices to both Zia and Hasina, requesting that details of their assets be submitted to the commission within one week.[76] Zia was asked to appear in court on 27 September in connection with a case for not submitting service returns for Daily Dinkal Publications Limited for years.[77] On 2 September, the government filed charges of corruption against Zia related to the awarding of contracts to Global Agro Trade Company in 2003.[10] She was arrested on 3 September.[78][11] She was detained in a makeshift prison on the parliament building premises.[79] On the same day, Zia expelled her party Secretary General Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan and Joint Secretary General Whip Ashraf Hossain for breaching party discipline.[80]

BNP standing committee members chose former Minister of Finance Saifur Rahman and former Minister of Water Resources Hafizuddin Ahmed to lead the party. Bangladesh Election Commission subsequently invited Hafizuddin's faction, rather than Zia's, to participate in talks, effectively recognizing the former as the legitimate BNP. Zia challenged this in court, but her appeal was rejected on 10 April 2008.[81]

Zia was released on bail on 11 September 2008 from her yearlong detention.[82]

In December 2008, the caretaker government organized general elections where Zia's party lost to the Awami League and its Grand Alliance (with 13 smaller parties) which took a two-thirds majority of seats in the parliament. Sheikh Hasina became the prime minister, and her party formed government in early 2009. Zia became the opposition leader of the parliament.

Eviction from the cantonment house

Zia's family had been living for 38 years in the 2.72-acre plot house at 6 Shaheed Mainul Road house in Dhaka Cantonment.[83] It was the official residence of her husband, Ziaur Rahman, when he was appointed as the Deputy Chief of Staff (DCS) of the Bangladesh Army.[84] After he became the President of Bangladesh, he kept the house as his residence. Following his assassination in 1981, the acting President Abdus Sattar, leased the house "for life" to Zia, for a nominal ৳101. When the army took over the government in 1983, Hussain Mohammad Ershad confirmed this arrangement.

On 20 April 2009, the Directorate of Military Lands and Cantonments handed a notice asking Zia to vacate the cantonment residence.[85][86] Several allegations and irregularities mentioned in the notice - first, Zia had been carrying out political activities from the house – which went against a condition of the allotment; second, one cannot get allotment of two government houses in the capital; third, a civilian cannot get a resident lease within a cantonment.[86] Zia vacated the house on 13 November 2010.[87] She then moved to the residence of her brother, Sayeed Iskandar, at the Gulshan neighborhood.[88]

.jpg.webp)

Boycotting 2014 election

Zia's party took a stance on not participating in the 2014 Bangladeshi general election unless it was administered under a nonpartisan caretaker government, but the then Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina rejected the demand.[89][90] The Bangladesh Awami League, led by Hasina, won the election in 232 seats (out of 300).[91] The official counts from Dhaka suggested that the turnout here averaged about 22 percent.[92]

In 2016, BNP announced its new National Standing Committee, in which Zia retained her position as the chairperson.[93][94][95]

.jpg.webp)

In 2017, the police conducted a raid on Zia's house search for "anti-state" documents.[96]

Charges and imprisonment in 2018

On 3 July 2008, during the 2007–08 caretaker government rule, ACC had filed a graft case, accusing Zia and five others of misappropriating over Tk 2.1 crore that had come from a foreign bank as grants for orphans.[97] According to the case, on 9 June 1991, $1.255M (Tk 4.45 crore) grant was transferred from United Saudi Commercial Bank to Prime Minister's Orphanage Fund - a fund that was created by then Prime Minister Zia shortly before the transfer of the grant as part of the embezzlement scheme.[97] On 5 September 1993, she issued a Tk 2.33 crore cheque from the Prime Minister's Orphanage Fund to the Zia Orphanage Trust on the pretext of building an orphanage in Bogra.[97] By April 2006, the deposited amount grew to Tk 3.37 crore with accrued interest. In April, June and July 2006, some of the money was transferred to bank accounts of three other accused – Salimul, Mominur and Sharfuddin – through different transactions.[98] On 15 February 2007, Tk 2.10 crore was withdrawn through pay orders from two of the FDR accounts.[97] Zia was accused of misappropriating that money by transferring the amount from a public fund to a private one.[98]

On 8 February 2018, during the Awami League government rule, Zia was sentenced to prison for five years in that corruption case.[99] Mobile phone jammers were installed at Bakshibazar court premises ahead of the verdict.[100] Her party claimed that the verdict was politically biased.[101] Zia was sent to the Old Dhaka Central Jail after the verdict.[102] She was imprisoned as the sole inmate at the jail since all the inmates had been transferred to the newly built Dhaka Central Jail in Keraniganj in 2016.[103][104] On 11 February 2018, Dhaka Special Judge's Court 5 directed the authorities of Dhaka Central Jail to provide first class division to Zia.[105] On 31 October 2018, the High Court raised her jail term to 10 years after ACC pleaded for a revision.[106]

On 30 October 2018, in another case, Zia Charitable Trust Graft Case, Zia was sentenced to 7 years of rigorous imprisonment.[107] Khaleda is also accused in other 32 cases including Gatco Graft Case, Niko Graft Case, Barapukuria Coalmine Graft Case, Darussalam Police Station Cases, Jatrabari Police Station Cases, Sedition Case, Bomb Attack on Shipping Minister Case, Khulna Arson Case, Comilla Arson Case, Celebrating Fake Birthday Case, Undermining National Flag Case and Loan Default Case.[108]

Zia's nomination papers to contest for Feni-1, Bogra-6 and Bogra-7 constituencies at the 2018 general election were rejected.[109] She was not able to contest because according to article 66 (2) (d) of the constitution, "a person shall be disqualified for election as, or for being, a member of parliament who has been, on conviction for a criminal offence involving moral turpitude, sentenced to imprisonment for a term of not less than two years, unless a period of five years has elapsed since his/her release".[110] Her party lost that general election to Awami League.[111]

Zia was admitted to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University for medical treatment on 1 April 2019.[16] The High Court and the Supreme Court rejected her bail plea on humanitarian grounds a total four times.[17]

On 25 March 2020, Zia was released from prison for six months, conditioned she would stay at her home in Gulshan and not leave the country.[17] The government issued this executive decision as per section 401 (1) of the Criminal Code of Procedure (CrPC).[17] As of November 2021, the term of her release has so far been extended four times.[112]

Illness

Zia has been suffering from chronic kidney conditions, decompensated liver diseases, unstable haemoglobin, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and other age-related complications.[113] In April 2021, several staff members in Zia's home tested positive for COVID-19. Zia also found to have contracted the virus but she exhibited no symptoms and recovered later.[114][115] On 28 November, the medical board formed for Zia's treatment announced that she had been suffering from liver cirrhosis.[116] Plea for allowing to fly abroad for medical care has been denied by the court.[117][118] Zia underwent treatment at Evercare Hospital in Dhaka during 27 April–19 June 2021, 12 October–3 November 2021 and again since 14 November 2021.[119][112] On 9 January 2022, Zia was transferred from critical care unit (CCU).[120]

Birth date discrepancy

Zia claims 15 August as her birthday, which is a matter of controversy in Bangladesh politics.[121][122] 15 August is the day many immediate family members of Zia's political rival, Sheikh Hasina, including her father Sheikh Mujibur Rahman were killed. As a result of the deaths, 15 August is officially declared National Mourning Day of Bangladesh.[121][123][124] None of Zia's government issued identification documents show her birthday on 15 August.[123][125] Khaleda Zia's father claimed that his daughter's date of birth is 5 September 1945.[126] Her matriculation examination certificate lists a birth date of 9 August 1945. Her marriage certificate lists 5 September 1945. Zia's passport indicates a birth date of 19 August 1945.[123][125] Kader Siddiqui, a political ally of Zia, urged her not to celebrate her birthday on 15 August.[122] The High Court filed a petition against Zia on this issue.[127][128]

Awards and honours

- On 24 May 2011, the New Jersey State Senate honoured Zia as a "Fighter for Democracy". It was the first time the state Senate had so honoured any foreign leader and reflects the state's increasing population of immigrants and descendants from South Asia.[129][130]

Eponyms

.jpg.webp)

- Begum Khaleda Zia Hall, a residential hall at Islamic University, Kushtia.[131]

- Deshnetri Begum Khaleda Zia Hall, a residential hall at the University of Chittagong.[132]

- Begum Khaleda Zia Hall, a residential hall at Jahangirnagar University.[133]

- Begum Khaleda Zia Hall, a residential hall at the University of Rajshahi.[134]

Bibliography

- Ullah, Mahfuz (18 November 2018). Begum Khaleda Zia: Her Life, Her Story. The Universal Academy. ISBN 978-984-93757-0-8.

References

Footnotes

- In 1947, Dinajpur district was split into West Dinajpur District in India and Dinajpur District in the then East Bengal.

Citations

- "'বেগম খালেদা জিয়া: হার লাইফ, হার স্টোরি'র মোড়ক উন্মোচন". BanglaNews24 (in Bengali). 19 November 2018.

- Mahmood, Sumon (8 February 2018). এই প্রথম দণ্ড নিয়ে বন্দি খালেদা. bdnews24.com (in Bengali).

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Zia, Begum Khaleda". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- "Khaleda Zia under 'virtual house arrest', army deployed". The Indian Express. 2013. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- "Khaleda Zia". PennState School of International Affairs. 2022. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- "#14: Begum Khaleda Zia, Prime Minister of Bangladesh". Forbes 100 Most Powerful Women in the World. 2004. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "#29 Khaleda Zia, Prime minister, Bangladesh". The 100 Most Powerful Women. 2005. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "#33 Khaleda Zia, Prime Minister, Bangladesh". The 100 Most Powerful Women. 31 August 2006. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Bangladesh ex-PM son detained". Al Jazeera. 16 April 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- "Ex-PM sued on corruption charges in Bangladesh". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 2 September 2007. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009.

- Anis Ahmed (3 September 2007). "Bangladesh ex-PM Khaleda Zia arrested on graft charge". Reuters. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- Skard, Torild (2014). "Khaleda Zia". Women of Power - Half a century of female presidents and prime ministers worldwide. Bristol: Policy Press. ISBN 978-1-44731-578-0.

- "'No one should abuse state power in such manner'". Dhaka Tribune. 30 October 2018.

- "2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Bangladesh". U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 30 March 2021.

- "Bangladesh: Guarantee Access to Health Care and Fair Trial Rights to Detained Former Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia". Amnesty International. 19 December 2019.

- "Khaleda taken to BSMMU". The Daily Star. 2 April 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Khaleda Zia freed, gets back home". The Daily Star. 26 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Correspondent, Senior; bdnews24.com. "Khaleda Zia's stay out of jail extended by another 6 months". bdnews24.com. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- আসছে 'বেগম খালেদা জিয়া: হার লাইফ, হার স্টোরি'. Bangla Tribune (in Bengali). 17 November 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- "Khaleda Zia". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- একনজরে খালেদা জিয়া. Jugantor (in Bengali). 8 February 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Z. A. Tofayell (1991). Bāṅmaẏa Bāṅgāli (in Bengali). Pān̐cagām̐o Prakāśanī. pp. 5–6.

- খালেদা জিয়ার মায়ের নবম মৃত্যুবার্ষিকী পালিত. The Daily Inqilab (in Bengali). 19 January 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Bogra: Khaleda Zia". bogra.org. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Tarique 'gave up Bangladesh nationality'". The Daily Star. 23 April 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Khaleda Zia's son Arafat Rahman Coco dies". bdnews24.com. 24 January 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Khurshid Jahan dies at CMH, 3rd Lead". bdnews24.com. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Ex-MP Sayeed Iskander passes away". The Daily Star. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Shamim Iskander arrested for ill-gotten wealth". The Daily Star. 19 July 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Charges pressed against Shamim Iskander, wife". The Daily Star. 19 August 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Khaleda spends quality time with relatives at BSMMU". The Daily Star. 5 June 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "1981: Bangladeshi president assassinated". BBC News. 30 May 1981. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- একনজরে খালেদা জিয়া. Jugantor (in Bengali). Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Liton, Shakhawat; Halder, Chaitanya Chandra (3 March 2014). "Ershad wanted to grab power after Zia killing". The Daily Star. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Rizvi, Gowher (1991). "Bangladesh: Towards Civil Society". The World Today. 47 (8/9): 155–160. JSTOR 40396362. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- "The Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in Bangladesh: 1982-1990" (PDF). White Rose eTheses Online. 2006. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- Uddin, AKM Jamal (January 2006). The Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in Bangladesh: 1982-1990 (PDF) (PhD). University of Leeds. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- "Bangladesh Confines Opposition Leaders". The New York Times. 4 March 1985. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- "Move Against Opposition Before Bangladesh Vote". The New York Times. 14 October 1986. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- "Bangladesh Frees Dissident Leaders". The New York Times. 11 December 1987. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- Khan, Manjur Rashid (2015). Amar Sainik Jibon: Pakistan theke Bangladesh আমার সৈনিক জীবনঃ পাকিস্তান থেকে বাংলাদেশ (in Bengali). Prothoma. p. 196. ISBN 978-984-33-3879-2.

- Dieter Nohlen; Florian Grotz; Christof Hartmann (2001). Elections in Asia: A data handbook. Vol. I. p. 537. ISBN 978-0-19-924958-9.

- Crossette, Barbara; Times, Special To the New York (1 March 1991). "General's Widow Wins Bangladesh Vote". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- Jackson, Guida M. (23 September 1999). Women Rulers Throughout the Ages: An Illustrated Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 433. ISBN 9781576074626.

- "Begum Khaleda Zia". Iowa State University. 6 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Hossain, Golam (February 1995). "Bangladesh in 1994: Democracy at Risk". Asian Survey. 35 (2): 176. doi:10.2307/2645027. JSTOR 2645027. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Ahamed, Kabir (2013). Bangladesh Education Statistics 2012. Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics. p. 261.

- "BB Orders & Other Statutes". Bangladesh Bank. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Bhattacharya, Debapriya (1998). Export Processing Zones in Bangladesh: Economic impact and social issues (PDF). International Labour Office. p. 9.

- Hossain, Golam (February 1995). "Bangladesh in 1994: Democracy at Risk". Asian Survey. 35 (2): 171–178. doi:10.2307/2645027. JSTOR 2645027. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Decentralisation". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Dieter Nohlen; Florian Grotz; Christof Hartmann (2001). Elections in Asia: A data handbook. Vol. I. p. 525. ISBN 978-0-19-924958-9.

- Alastair Lawson (4 October 2001). "Analysis: Challenges ahead for Bangladesh". BBC News.

- "Analysis: Challenges ahead for Bangladesh". BBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Violence Breaks out in Bangladesh's Capital Dhaka". China News and Report. Xinhua News Agency. 17 October 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- "Renewed violence hits Bangladesh". BBC News. 28 October 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Roy, Pinaki (28 October 2006). "Hasan 'unwilling' to be caretaker chief". The Daily Star. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- "KM Hasan steps aside for the sake of people". The Daily Star. 29 October 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Habib, Haroon (30 October 2006). "President takes over in Bangladesh". The Hindu. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Rahman, Waliur (8 January 2007). "Is Bangladesh heading towards disaster?". BBC News. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- "Iajuddin wants to open talks with alliances". The Daily Star. 30 November 2006. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Khaleda going to Saudi Arabia". BDnews24. 7 August 2012. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "CPC, Bangladesh Nationalist Party to further cooperation". Xinhua. 18 October 2012. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Khaleda seeks China's help". The Daily Star. 21 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Stalled Padma Bridge Project". Daily Sun. 20 September 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Chinese help for 2nd Padma bridge assured: BNP". The New Nation. 23 October 2012. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- "China ready to help build 2nd Padma bridge: BNP". News Today. 23 October 2012. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Khaleda Zia arrives in the capital, meets Sushma". Deccan Herald. 28 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "India and Bangladesh Embraceable you". The Economist. 30 July 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

Mrs Zia's family dynasty ... is as against India as Sheikh Hasina's is for it.

- "Khaleda Zia assures counter-terror cooperation to India". Yahoo News. Indo Asian News Service. 29 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ভারতবিরোধী কর্মকাণ্ডে বাংলাদেশের মাটি ব্যবহার করতে দেওয়া হবে না: খালেদা জিয়া [Khaleda Zia: No anti-India activity would be allowed to use the soil of Bangladesh]. BBC Bangla (in Bengali). 29 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Politicians barred from visiting Khaleda Zia's residence". The Hindu. 11 April 2007. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Khaleda agrees to fly out with Arafat : Tarique may join them later". The Daily Star. 17 April 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- "Opposition welcomes B'desh U-turn". BBC News. 26 April 2007. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Bangladesh High Court orders government to explain restrictions on ex-prime minister". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 8 May 2007. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008.

- "Hasina, Khaleda given 7 days for wealth report". The Daily Star. 18 July 2007. p. 1. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Khaleda asked to appear before court September 27". The Daily Star. 27 August 2007.

- "Ex-PM is arrested in Bangladesh". BBC News. 3 September 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- "Tarique freed on bail". The Daily Star. 4 September 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Bangladesh party splits over reform demands". Reuters. 15 September 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Bangladesh court rejects Zia appeal". Al Jazeera. 10 April 2008.

- "Freed Khaleda to join talks, contest polls". The Daily Star. 12 September 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Govt cancels lease of Khaleda's Cantt house". The Daily Star. 9 April 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Quiet day at Gulshan". The Daily Star. 15 November 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Eviction notice for Khaleda Zia". 8 April 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Tearful Khaleda reaches Gulshan office". bdnews24.com. 13 November 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "I am evicted". The Daily Star. 14 November 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Dozens hurt in Bangladesh clashes". BBC. 13 November 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- Ahmed, Farid. "Bangladesh ruling party wins elections marred by boycott, violence". CNN. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "Clashes in boycotted Bangladesh poll". BBC. 5 January 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "Bangladesh election violence throws country deeper into turmoil". The Guardian. 6 January 2014. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- Barry, Ellen (5 January 2014). "Low Turnout in Bangladesh Elections Amid Boycott and Violence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "BNP's names 17 members of the policymaking Standing Committee". bdnews24.com.

- "BNP names members of its leaders' families in new committee". bdnews24.com.

- "Vision 2030: Bangladesh Nationalist Party – BNP" (PDF). Prothom Alo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- "Bangladesh Police Raid Khaleda Zia's Office". News18. 20 May 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "Khaleda, Tarique sued for embezzling Tk 2cr". The Daily Star. 4 July 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Khaleda lands in jail". The Daily Star. 9 February 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Clashes as Bangladesh ex-PM jailed". BBC News. 8 February 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Mobile network jammer installed at court premises". The Daily Star. 8 February 2018.

- "Bangladesh former Prime Minister guilty of corruption". The Independent. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Star Online Report (8 February 2018). "Khaleda Zia enters old central jail". The Daily Star. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- "Bangladesh opposition leader Zia hospitalised: lawyer". Yahoo News. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- Billah, Masum (5 September 2018). "Anger defines the day for BNP chief Khaleda Zia". bdnews24.com. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Court orders to give division to Khaleda Zia". Dhaka Tribune. 11 February 2018.

- "Zia Orphanage Graft Case: Khaleda's jail term raised to 10 years". The Daily Star. 31 October 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Zia Charitable Trust Graft Case: Khaleda jailed for 7 years". The Daily Star. 30 October 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "34 Cases Against Khaleda". The Daily Star. 8 February 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "All of Khaleda Zia's candidacies rejected". Dhaka Tribune. 2 December 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Mahmud, Faisal (8 February 2018). "Khaleda Zia jailed for five years in corruption case". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- "Bangladesh PM wins landslide election". BBC. 31 December 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Docs closely monitoring Khaleda's condition". The Daily Star. 20 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "Khaleda fighting for life: BNP". The Daily Star. 19 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "How Khaleda Zia contracted Covid-19". The Daily Star. 11 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- "Khaleda slightly improved". The Daily Star. 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- "Doctors: Khaleda Zia has liver cirrhosis". Dhaka Tribune. 28 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "Bangladesh doctors fear for opposition leader Khaleda Zia's life". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "Bangladeshi doctors fear for Khaleda Zia's life". Dawn. 29 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "Khaleda Zia shifted to CCU". Dhaka Tribune. 14 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- UNB (10 January 2022). "Khaleda Zia shifted to cabin from CCU". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- "15 August isn't Khaleda's birthday: Joy". Natun Barta. 15 August 2013. Archived from the original on 20 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "Stop celebrating August 15 birthday". The Daily Star. 24 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "Ex-Bangladesh PM stretches limits of political rivalry with PM Sheikh Hasina by celebrating birthday on August 15". Yahoo News-1. 16 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "Same old trend". The Daily Star. 17 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "Huge cakes are cut on Khaleda Zia's 'birthday'". bdnews24.com. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "খালেদা প্রসঙ্গে তার বাবা: আমার মেয়েকে রাজনীতিকরা এক্সপ্লয়েট করছে" [Khaleda's father: My daughter is being exploited by politicians]. Monthly Nipun (in Bengali). May 1984.

- "HC hears petition on Khaleda's birthday tomorrow". The Daily Sun. 13 June 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "Notice to ex-Bangladeshi PM for celebrating b'dday on August 15". Zee News. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "New Jersey Senate honours Khaleda". The Daily Star. 25 May 2011.

- "BNP goes gaga over US honour". The Daily Star. 27 May 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Islamic University". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- "Deshnetri Begum Khaleda Zia Hall". University of Chittagong. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Begum Khaleda Zia Hall". Jahangirnagar University. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Welcome to Begum Khaleda Zia Hall". University of Rajshahi. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

External links

- "Life Sketch: Begum Khaleda Zia". Permanent Mission of Bangladesh to the United Nations. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009.

- Works by or about Khaleda Zia in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Barbara Crossette (17 October 1993). "Conversations: Khaleda Zia; A Woman Leader for a Land That Defies Islamic Stereotypes". The New York Times.

- William Green; Alex Perry (10 April 2006). "We Have Arrested So Many". Time. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011.

- Alex Perry (3 April 2006). "Rebuilding Bangladesh". Time. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010.