Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (Spanish: [beˈnito ˈpaβlo ˈxwaɾes gaɾˈsi.a] (![]() listen); 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872)[1] was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. A Zapotec, he was the first indigenous president of Mexico and the first indigenous head of state in the postcolonial Americas.[2]

listen); 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872)[1] was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. A Zapotec, he was the first indigenous president of Mexico and the first indigenous head of state in the postcolonial Americas.[2]

The Most Excellent Benito Juárez | |

|---|---|

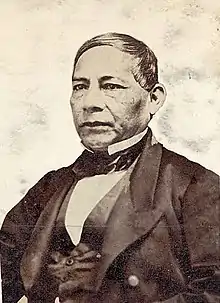

Benito Juárez, c. 1872 | |

| 26th President of México | |

| In office 15 January 1858 – 18 July 1872 | |

| Preceded by | Ignacio Comonfort |

| Succeeded by | Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada |

| President of the Supreme Court | |

| In office 11 December 1857 – 15 January 1858 | |

| Preceded by | Luis de la Rosa Oteiza |

| Succeeded by | José Ignacio Pavón |

| Secretary of the Interior of Mexico | |

| In office 3 November 1857 – 11 December 1857 | |

| President | Ignacio Comonfort |

| Preceded by | José María Cortés |

| Succeeded by | José María Cortés |

| Governor of Oaxaca | |

| In office 10 January 1856 – 3 November 1857 | |

| Preceded by | José María García |

| Succeeded by | José María Díaz |

| In office 2 October 1847 – 12 August 1852 | |

| Preceded by | Francisco Ortiz Zárate |

| Succeeded by | Lope San Germán |

| Secretary of Public Education of Mexico | |

| In office 6 October 1855 – 9 December 1855 | |

| President | Juan Álvarez |

| Preceded by | José María Durán |

| Succeeded by | Ramón Isaac Alcaraz |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Benito Pablo Juárez García 21 March 1806 San Pablo Guelatao, Oaxaca, New Spain |

| Died | 18 July 1872 (aged 66) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Resting place | Panteón de San Fernando |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Political party | Liberal Party |

| Spouse | Margarita Maza

(m. 1843; died 1871) |

| Alma mater | Institute of Sciences and Arts of Oaxaca |

| Profession | Lawyer, judge, politician |

| Signature |  |

Born in Oaxaca to a poor rural family and orphaned as a child, Juárez was looked after by his uncle and eventually moved to Oaxaca City at the age of 12, working as a domestic servant. Aided by a lay Franciscan, he enrolled in a seminary and studied law at the Institute of Sciences and Arts, where he became active in liberal politics. After his appointment as a judge, he married Margarita Maza, a woman of European ancestry from a socially distinguished family in Oaxaca City,[3] and rose to national prominence after the ouster of Antonio López de Santa Anna in the Plan of Ayutla. He participated in La Reforma, a series of liberal measures under the presidencies of Juan Álvarez and Ignacio Comonfort which culminated in the Constitution of 1857. With Comonfort's resignation during the Reform War, Juárez, as President of the Supreme Court, became constitutional President of Mexico. He led Mexican liberals against conservatives during the conflict and prevailed against the Second French Intervention.

Juárez tied liberalism to Mexican nationalism and tenaciously held the presidency until his death in 1872. He asserted his leadership as the legitimate head of the Mexican state in opposition to Maximilian I, whom the French Empire installed with the support of Mexican conservatives. After being elected president in 1861, he extended his term during the French Intervention and was re-elected in 1867 and 1871 to lead the Restored Republic, but with growing opposition from fellow liberals.[4][5] During his presidency, he took a number of controversial measures, including his negotiation of the McLane–Ocampo Treaty, which would have granted the United States extraterritorial rights across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; a decree extending his presidential term for the duration of French Intervention; his proposal to revise the liberal Constitution of 1857 to strengthen the power of the federal government; and his decision to run for reelection in 1871.[6][7] His opponent, liberal general, and fellow Oaxacan Porfirio Díaz opposed his re-election and rebelled against Juárez in the Plan de la Noria.

Juárez came to be seen as "a preeminent symbol of Mexican nationalism and resistance to foreign intervention."[8][9] He looked to the United States as a model for Mexican development, as opposed to previous administrations, whose political vision was more inclined towards Europe. His policies advocated civil liberties, equality before the law, the sovereignty of civilian power over the Catholic Church and the military, the strengthening of the Mexican federal government, and the depersonalization of political life.[10] For Juárez's success in ousting European invasion, Mexicans considered Juárez's tenure as a time of a "second struggle for independence, a second defeat for the European powers, and a second reversal of the Conquest."[11]

After his death, the city of Oaxaca added "de Juárez" to its name in his honor, and numerous other places and institutions have been named after him. He is the only individual whose birthday (21 March) is celebrated as a national public and patriotic holiday in Mexico.

Early life and education

Benito Juárez was born in an adobe house in San Pablo Guelatao, Oaxaca, located in the mountain range since named for him and now known as the Sierra Juárez. His parents, Brígida García and Marcelino Juárez were Zapotec peasants. He had two older sisters, Josefa and Rosa. Both parents died of complications of diabetes when Juárez was three years old. His grandparents died shortly after, and Juárez was raised by his uncle Bernardino Juárez.[12][13] He described his parents as "indios de la raza primitiva del país," that is, "Indians from the primitive race of the country."[13]

He worked in the cornfields and as a shepherd until the age of 12. His sister had moved to the city of Oaxaca for work, and that year he moved to the city to attend school.[14] There he took a job as a domestic servant in the household of Antonio Maza, where his sister worked as a cook.[14] At the time, he spoke only Zapotec.

At this critical time, Juárez was also helped by a lay Franciscan and bookbinder, Antonio Salanueva, who was impressed by the youth's intelligence and desire for learning. Salanueva arranged for his admission to the city's seminary so that he could train to become a priest. His earlier education was elementary, but he soon began studying Latin and completed the secondary curriculum while still too young to be ordained. But, realizing he had no interest in becoming a priest, Juárez began studying law at the Institute of Sciences and Arts, founded in 1827. It was a center of liberal intellectual life in Oaxaca, and he graduated with a law degree in 1834.[2]

Prior to his graduation, Juárez sought political office and was elected to the Oaxaca city council in 1831. After practicing law for several years, in 1841 he was appointed as a civil judge.[8]

Political career

Juárez entered state politics, eventually rising to the state governorship. In 1853 he went into exile in the U.S. after running afoul of General Antonio López de Santa Anna and formed important ties with fellow Mexican liberals and Cuban nationalists. He rose to prominence after the ouster of Santa Anna and was involved in the drafting of legislation that came to be known as La Reforma. Conservatives pushed back against the Liberals' sweeping program, forcing the resignation of President Ignacio Comonfort, which brought Juárez to the Presidency because he was head of the Supreme Court. Civil war with the rebel Conservatives ensued, with the Liberals victorious in 1860. Juárez was elected to the presidency in 1861, but Conservatives allied with France, which invaded Mexico in 1862 and placed Maximilian von Habsburg as leader of the Second Mexican Empire. Despite the fracturing of liberalism, Juárez steadfastly continued to resist the foreign invasion and replacement of the republic. He came to embody Mexican nationalism. Following the fall of the Second Mexican Empire in 1867, liberal politicians renewed their factional disputes, often attacking Juárez, who sought the strengthening of the powers of the presidency and central governance. His death in office in 1872 ended that phase of Mexican politics.

Early career in Oaxaca

Juárez's experiences in political life in Oaxaca were crucial to his later success as a leader.[2] His political affiliation with liberalism developed at the Institute of Arts and Science and his ability to rise in Oaxaca state politics was due to the lack of an entrenched political class of criollos, Mexicans of Spanish descent. The relative openness of the system allowed him and other newcomers to enter politics and gain patronage.[15] He developed a political base and gained an understanding of political maneuvering.

Juárez graduated as a lawyer and set up a law practice in 1834. As a lawyer, Juárez took cases of indigenous villagers. Community members of Loxicha, Oaxaca hired him for their denunciation of a priest, whom they accused of abuses. He did not win the case, and was thrown into jail along with community members, "thanks to the collusion between Church and the state," writing later that it "strengthened in me the goal of working constantly to destroy the pernicious power of the privileged classes."[16] Juárez and other liberals saw equality before the law as a transformative principle for Mexico, as in the post-independence era legal privileges were accorded to the Mexican Catholic Church and the army, and continued some protections for indigenous communities.[17]

He served as a civil judge in 1841 and became part of the Oaxaca state government, led by liberal governor Antonio León (1841–1845).[18] He became a prosecutor in the Oaxaca state court and was elected to the state legislature in 1845. Juárez was subsequently elected to the federal legislature, where he supported Valentín Gómez Farías, who instigated liberal reforms including limitations on the power of the Catholic Church. With the return to the presidency of Antonio López de Santa Anna in 1847, Juárez returned to his practice in Oaxaca.[8][19] He was elected governor of Oaxaca, serving from 1847 to 1852. During his tenure as governor, Juárez supported the Mexican war effort during the Mexican–American War. Recognizing that the war was lost, he refused Santa Anna's request to regroup and raise new forces. This, as well as his objections to the corrupt military dictatorship of Santa Anna, resulted in his going into exile in New Orleans in 1853.[20]

Exile in New Orleans

Like other Mexican liberals, Juárez looked to the U.S. as a model of development for Mexico, while conservatives looked to Europe, especially France and Britain.[21] When Santa Anna returned to power in 1853, many liberals went into exile in the U.S., including Juárez. In New Orleans Juárez was brought into a multifaceted and international new milieu. His day job was as a cigar maker in one of the city's factories,[22][23] while his wife remained in Mexico with their children, and were looked after by liberal loyalists, Ignacio Mejía and Domingo Castro.[24] Since he had not enriched himself as governor of Oaxaca, both Juárez and his wife had economic hardships, but she managed to send him some of her own money there to help with his support.[25] Other opponents of Santa Anna were also in exile there, including Melchor Ocampo of Michoacán, who was fiercely anti-clerical.[26] The year and a half Juárez spent in New Orleans (1853–55) was important to Juárez's and other exiles' political formation. The exiles plotted a return to Mexico and the overthrow of Santa Anna. In 1854, Juárez helped draft the liberals' Plan of Ayutla, a document calling for Santa Anna's deposing and a convention to draft a new constitution. Faced with growing opposition, Santa Anna resigned in 1855.[27]

Juárez's time in New Orleans broadened his horizons, meeting not just fellow exile Mexican liberals, but also Cuban separatist exile, Pedro Santacicilia, who later married Juárez's oldest child. Cuba was still a Spanish colony, not gaining its independence until 1898, and Cuban nationalists sought independence. For Mexico, the existence of a Spanish colony geographically close to Mexico was seen as a potential threat. It had been the springboard for Spain's unsuccessful attempts to reconquer Mexico. Santacicilia and his fellow Cuban business partner Domingo de Goicuría were important to the Mexican liberal cause, sending arms to Guerrero and acting on liberals' behalf in Veracruz in the War of the Reform. During the Second French Intervention, Santacilia helped Juárez's wife and children in their New York exile.[28]

Liberal Reform, 1855–1857

With Santa Anna's resignation, Juárez returned to Mexico from his exile in the U.S. and became part of the activist puro (pure) faction of Liberals. They formed a provisional government under General Juan Álvarez, the strongman of Guerrero state, inaugurating the period known as La Reforma, or Liberal Reform.[29] Juárez served as Minister of Justice and ecclesiastical affairs. During this time, he drafted the law named after him, the Juárez Law, which declared all citizens equal before the law, and restricted the privileges (fueros) of the Catholic Church and the Mexican army. President Álvarez signed the draft into law in 1855.[30]

The Reform laws curtailed the traditional powers of the military and the Catholic Church in Mexico. The Lerdo law forced the sale of Church lands as well as those of indigenous communities. The Juárez Law was subsequently incorporated into the Mexican Constitution of 1857. The laws attempted to create a market economy and modern civil society based on the model of the United States. Juárez had direct no role in drafting the constitution since he had returned to Oaxaca, where he served again as governor.[30]

The Constitution of 1857 was promulgated in February and the following president, Ignacio Comonfort, appointed Juárez as Minister of Government in November. He was elected as President of the Supreme Court of Justice, an office that virtually put its holder as the successor to the President of the Republic.[30]

War of the Reform, 1858–1860

Conservatives rejected the new constitution, promulgated on 11 March 1857, and sought to overturn it. Led by General Félix María Zuloaga, Conservatives sought to nullify the constitution and issued the Plan of Tacubaya on 17 December 1857. Recently elected president, Ignacio Comonfort, a moderate liberal, opposed the constitution, which gave more power to Mexican states and further curtailed the power of the executive by making Congress superior to it. Comonfort signed onto the Conservatives' plan, which called for nullifying the constitution, drafting a new constitution, and leaving Comonfort as president with extraordinary powers in the interim. Comonfort "felt that by temporarily assuming dictatorial powers he could hold the extremists on both sides in check and pursue a middle course, always his object. It soon became obvious that such an assumption was merely wishful thinking."[31] Juárez, Ignacio Olvera, and many other liberal deputies and ministers were arrested. For the conservatives, these actions did not go far enough, and on 11 January 1858, Zuloaga demanded Comonfort's resignation. Comonfort re-established Congress, and liberated all prisoners including Juárez, before resigning as president. The conservative insurrectionists proclaimed Zuloaga as president on 21 January 1858.[32]

Under the terms of the 1857 Constitution, the President of the Supreme Court of Justice became interim President of Mexico until a new election could be held. With Comonfort's resignation, Juárez was acknowledged as president by liberals on 15 January 1858 and assumed leadership of the Liberal side of the civil war known as the War of the Reform (Guerra de Reforma) (1858–60). During the war, Mexico had rival governments of the liberals under Juárez, in a constitutional succession, and the conservatives under Félix María Zuloaga.[32] The contest would be decided on the field of battle. With the conservatives in control of Mexico City, Juárez and his government evacuated and moved first to Querétaro and later to Veracruz, whose customs revenues were used to fund the government.

On 4 May 1858, Juárez arrived in Veracruz where the government of Manuel Gutiérrez Zamora was stationed with General Ignacio de la Llave.[33] His wife and children were waiting for his arrival on the dock at Veracruz's port, along with a large part of the population that had flooded the pier to greet him.

Juárez lived many months in Veracruz without incident until conservative General Miguel Miramón's attacked the port on 30 March 1859. On 6 April, Juárez received a diplomatic representative of the United States Government: Robert Milligan McLane. The U.S. was seeking a route for transit from the Caribbean to the Pacific Ocean, and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec was the narrowest crossing in Mexico between the bodies of water. With Juárez needing allies against the conservatives, Juárez went forward with a formal treaty between the two governments. Melchor Ocampo signed for Mexico on McLane-Ocampo Treaty in December 1859. Juárez was saved from the implementation of the treaty, which would undermine Mexico's sovereignty, because U.S. President James Buchanan was unable to secure ratification of the treaty by the U.S. Senate. Despite the failure of the treaty, Juárez's government received aid from the U.S. that enabled the liberals to overcome the conservatives' initial military advantage. Juárez's government successfully defended Veracruz from assault twice during 1860 and recaptured Mexico City on 1 January 1861.

On 12 July 1859, Juárez decreed the first regulations of the "Law of Nationalization of the Ecclesiastical Wealth." This enactment prohibited the Catholic Church from owning properties in Mexico.[34] The Catholic Church and the regular army supported the Conservatives in the Reform War. On the other hand, the Liberals had the support of several state governments in the north and central-west of the country, as well as that of President Buchanan's government.

Due to the initial weakness of the Juárez administration, Conservatives Félix María Zuloaga and Leonardo Márquez had the opportunity to reclaim power. To counter this, Juárez petitioned Congress to give him emergency powers. The liberal members of Congress denied the petition, believing they had to preserve their constitutional government achieved only after a damaging civil war. They did not believe that Juárez, who had implemented the constitution, should violate it by taking extraordinary powers. However, after groups of Conservatives ambushed and killed major liberal politicians and intellectuals Melchor Ocampo and Santos Degollado in 1861, liberals were outraged. Juárez took "extreme measures" to deal with the conservatives. After the scandal of Ocampo's murder, the liberal-majority Congress agreed to increase Juárez's powers to defeat the remaining conservative forces.[35]

Constitutional Presidency (1861–1862)

After the defeat of the Conservatives on the battlefield, in March 1861 elections were held and Juárez was elected president in his own right under the Constitution of 1857. Juárez called for elections to be held in January 1861, but they were not held until March. At this point, Juárez had two liberal rivals in the election, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada and Jesús González Ortega. Melchor Ocampo supported Juárez, pointing to Lerdo's statements late in the Reform War that the liberal republic could not win except with the armed aid of the Americans. Ocampo opposed the Lerdo Law and its implementation as unjust. Guillermo Prieto also attacked Lerdo and favored Juárez. As the Juárez government was attempting to regain control of the country's financial situation, it allowed conservative functionaries of the treasury to return to their positions, for which Juárez drew criticism. Prieto countered that the conservative bureaucrats had the relevant expertise. During the campaign, Lerdo died of typhoid, leaving González Ortega as Juárez's only rival. González Ortega was a popular military leader who had delivered significant victories against the conservatives. He then served as Minister of War in Juárez's cabinet, while maintaining his command of the troops of the Zacatecas Division. He resigned from the cabinet, but despite civil unrest in the capital calling for his reinstatement, he did not rebel or allow his name to be used by armed supporters. The civilian government of Juárez prevailed and he won the 1861 election.[36]

Although the conservatives had been defeated on the battlefield, they remained active as guerrillas throughout the country. As congress was reconvening for the first time since 1857, they received word that Melchor Ocampo had been executed in his home state of Michoacán by a conservative guerrilla band. Santos Degollado, who had been dismissed from his command, requested permission from congress to pursue Ocampo's killers. He too was killed by the guerrillas on June 15. González Ortega took charge of routing the guerrillas there.[37] Conservative General Leonardo Márquez took refuge in the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro and refused to recognize Juárez as president. He was blamed for the murders of Ocampo and Degollado. In hiding in March 1861, Márquez declared that Juárez and his supporters were traitors and therefore subject to summary execution.[38]

In the wake of the civil war and the demobilization of combatants, Juárez established the Rural Guard or Rurales, aimed at bringing public security, particularly as banditry and rural unrest grew. Many brigands and bandits had allied themselves with the liberal cause during the civil war. When the conflict finished, many became guerrillas and bandits again.[39] Juárez's Minister of the Interior, Francisco Zarco, oversaw the founding of the Rurales. The creation of the police force controlled by the President was done quietly because it violated the federalist principles of Mexican liberalism. The force's creation indicated Juárez had adopted centralist positions as he confronted continuing rural unrest. As a pragmatic solution, the force consisted of former bandits converted into policemen.[40]

Juárez's government also faced international conflicts. Given the government's desperate financial straits, Juárez contemplated suspending payments on foreign debt, which could trigger international intervention. The British government sent diplomat Sir Charles Lennox Wyke to find a solution to the financial crisis.[41] Juárez's Minister of Finance Manuel María de Zamacona negotiated an agreement with Wyke, concluded on 21 November 1861, but the treaty was repudiated by congress.[42] When Juárez suspended repayments of interest on foreign loans taken out by the defeated conservatives on 17 July, it set in motion intervention from European powers. Spain, Britain, and France infuriated over unpaid Mexican debts, agreed to the Convention of London, a joint effort to ensure that debt repayments from Mexico would be forthcoming and sent a joint expeditionary force that seized the Veracruz Customs House in December 1861. Spain and Britain soon withdrew, but French Emperor Napoleon III intended to overthrow the Juárez government and establish a Second Mexican Empire with the support of remaining Conservatives, beginning the Second French intervention, with Liberals attempting to oust the foreign invaders and their Conservative allies and restore the Republic.[43]

The outbreak of the conflict occurred during the American Civil War, which broke out in April 1861. Despite that, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln's government was aware of the liberals' peril. U.S. Secretary of State William Seward attempted to find a solution to the debt crisis, floating the possibility of the U.S. assuming the interest charges on the Mexican debt and placing a lien on public lands in Mexican northern states of Baja California, Chihuahua, Sonora, and Sinaloa. Mexican representative in the U.S. Matías Romero attempted to promote the resolution but was rejected by the U.S. Senate. The European powers invited the U.S. to join their coalition but declined given its adherence to the Monroe Doctrine.[44]

After much contention among the liberals and after it became clear that the European powers would indeed intervene, Juárez was granted extraordinary powers by congress to deal with the crisis. The sole restriction on his taking any step necessary in the current crisis was that "he must maintain the nation's independence and territorial integrity, the form of government established by the constitution, and the principles of the laws of Reform."[45]

Juárez and the French Intervention (1862–67)

During the French invasion following Juárez's decision to cancel debt payments to European powers, Juárez came to embody implacable Mexican nationalism against foreign invaders and during the crisis led a largely unified liberal republic. As with the Reform War, Mexico again had two governments, the conservatives with their French allies and that of the constitutional, elected president Juárez. The French invasion challenged the political order in Mexico, but Republican forces under Ignacio Zaragoza won an initial victory over the monarchists on 5 May 1862, the Battle of Puebla, celebrated annually as Cinco de Mayo. The French were forced to retreat to the coast for a year, but they advanced again in 1863 and captured Mexico City on 10 June 1863. With the invasion, congress ratified the grant to Juárez of extraordinary powers on 27 October 1862 and again on 27 May 1863.[46]

Juárez left the capital to set up a government in internal exile, though the rump United Mexican States had very little authority or territorial control over most of the non-occupied territory. Juárez headed north, first to San Luis Potosí (9 June – 22 December 1863), Saltillo (9 January; 14 February – 2 April opposed by his old rival Santiago Vidaurri); then to the arid north of Chihuahua near the U.S. border, (12 October 1864 – 10 December 1866), with time in El Paso del Norte (present-day Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua) and finally to the capital of the state, Chihuahua City, where he set up his cabinet. Juárez deposed Vidaurri from his stronghold in Nuevo León-Coahuila, separating the states on 26 February 1863 and Vidaurri defected to the conservative monarchists on 7 September 1863.[47]

A conservative regency council comprising Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, natural son of José María Morelos; Bishop Pelagio Antonio de Labastida, and General Mariano Salas established a conservative, monarchist regime 18 June 1863. Maximilian von Habsburg, younger brother of Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria, accepted the invitation to become emperor on 3 October 1863 and was proclaimed Emperor as Maximilian I of Mexico on 20 April 1864, with the backing of Napoleon III and Mexican conservatives.[46]

Juárez's term as president expired on 1 December 1865, and arguably the head of the Supreme Court would succeed as president. Jesús González Ortega could legally claim the presidency.[48] Juárez issued two decrees to undermine Ortega's claims and retain office. One decree extended the terms of the President and head of the Supreme Court until elections could be held. Juárez "believed he had the power to extend his term ... [and] became convinced that the nation would approve his continuing his term." Juárez exceeded his constitutional powers in remaining in office, but given the extraordinary times, he had considerable support.[49]

In response to the French invasion and the elevation of Maximilian as Emperor of Mexico, Juárez sent General Plácido Vega y Daza to California to gather Mexican American sympathy for republican Mexico. Maximilian offered Juárez amnesty and later the post of prime minister, but Juárez refused to accept a government imposed by foreigners, or a monarchy. The US government was sympathetic to Juárez, refusing to recognize Maximilian and opposing the French invasion as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine. Most of its attention was taken up by the American Civil War.[50]

Juárez's wife, Margarita Maza, and their children spent the invasion in exile in New York, where she met several times with U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, who received her as the First Lady of Mexico. The careers of Juárez and Abraham Lincoln have been compared, as the two presidents had shared humble social origins, a law career, a rapidly ascending political career in their home states, and a presidency that began under the auspices of a civil war that made long-lasting reform a necessity, but they never met nor exchanged correspondence.[51]

Following the end of the American Civil War and Lincoln's assassination, Andrew Johnson succeeded in the US presidency. He demanded that the French evacuate Mexico and imposed a naval blockade in February 1866. When Johnson could not get sufficient support in Congress to aid Juárez, he allegedly had the Army "lose" some supplies (including rifles) "near" (across) the border with Mexico, according to U.S. General Philip Sheridan's journal account.[52] In his memoirs, Sheridan stated that he had supplied arms and ammunition to Juárez's forces: "... which we left at convenient places on our side of the river to fall into their hands".[53]

Faced with US opposition to a continuing French presence and a growing threat on the European mainland from Prussia, French troops began pulling out of Mexico in late 1866. Maximilian's liberal views had cost him support from Mexican conservatives as well. In 1867, the last of the Emperor's forces were defeated. Maximilian was sentenced to death by a military court, a retaliation for Maximilian's earlier orders for the execution of republican soldiers (although some historians point to the fact that the original "Black Decree" was from Juárez – who had people executed, without trial, for "helping" his enemies, whereas Maximilian often pardoned people who had fought against him). Despite national and international pleas for amnesty, Juárez refused to commute the sentence. Maximilian was executed by firing squad on 19 June 1867 at Cerro de las Campanas in Querétaro. His body was returned to Vienna for burial.[54]

Restored Republic (1867–1872)

The period following the expulsion of the French and up to the revolt of Porfirio Díaz in 1876 is now known in Mexico as the Restored Republic.[55] The period includes the last years of the Juárez presidency and, following his death in office in 1872, that of fellow civilian politician Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada.

Under ordinary circumstances, Juárez's presidential term would have ended in 1865 and elections held, but during the French invasion, he continued in the presidency as head of state in domestic exile. With the ouster of the French in 1867, other liberals now objected to Juárez's remaining in power without an electoral mandate. The broad liberal front against the French had splintered and rivals to Juárez emerged. Liberals had not been unified in their support of the Constitution of 1857, and with the exit of the French, simmering conflicts between liberal factions in abeyance during the intervention came to the fore. Juárez sought the legal means to extend his time in power, proposing that the Constitution be amended to allow for a third term and increase the power of the executive against that of the legislature. For Juárez's opponents, this was seen as a confirmation that Juárez wished to keep a personal grip on power.[56] The Constitution had been aimed at limiting the power of the Catholic Church and the army as institutions and invigorating the power of Mexican states against the power of the central government. The constitution also made the legislative branch superior to the executive, to forestall personalist power. During the intervention, the republic barely continued to exist and the structure of the constitutional division of powers was inoperative. Juárez realized when he returned to the presidency in 1867 that presidential powers were diminished. In the face of opposition, Juárez built a set of alliances to strengthen the power of the central government and make the constitutional system work. His critics saw his actions as building a personal dictatorship.[57]

The Restored Republic was a politically unstable time in Mexico, with multiple insurrections.[58] A perceived challenge to Juárez came early. In 1867, the liberals' former nemesis, General Antonio López de Santa Anna, and the President of Mexico multiple times sought to return to Mexico from exile. The U.S. had pledged to support Juárez and prevented Santa Anna from disembarking in Veracruz, his home region and political base. Veracruz was still in French imperial hands when Santa Anna attempted to land in June 1867, and the possibility that he might seize the port from them was a distinct possibility. This could have paved the way for a political comeback threatening Juárez. Juárez's forces diverted the general, who landed in Sisal, Yucatán. He was arrested before a military court on 14 July 1867. He was accused of being a traitor to Mexico, and Juárez sought the use of the law of 25 January 1862 that mandated death for traitors, a fate for Maximilian and two of his generals. The military tribunal decided that Santa Anna should be sentenced to eight years of further exile. Juárez had been expecting a sentence of death and was proceeding to have Santa Anna's landed property confiscated and sold off. Juárez issued a general amnesty for all political opponents in October 1870 but explicitly excluded Santa Anna. The general responded angrily, listing his military deeds for Mexico, asking contemptuously where the civilian Juárez was then, and calling him a "dark Indian," a "hyena," and "a symbol of cruelty." But only after Juárez died in office was Santa Anna able to return to Mexico.[27]

The War of the Reform and the French Intervention had forestalled any serious implementation of the Liberal reforms. With the defeat of the French and their Mexican conservative allies, the way seemed clear to institute changes. Juárez had turned the opposition to the French Intervention into a war of national liberation of the Republic from a foreign invader rather than as a victory of Mexican liberalism. For that reason, he had considerable political support which could be translated into actions.[59]

In a controversial move, Juárez ran for re-election in 1871. His loyal political ally, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada had expected to succeed Juárez in that election, since Juárez had already been criticized for apparently holding onto power. When Lerdo served in Juárez's cabinet post-1867 and had forged political alliances with a number of state governors and with congressmen. It became clear that Juárez was going to run for re-election, and Lerdo resigned from the cabinet. Lerdo and Díaz ran for the presidency with none of them achieving a majority on his own, but rivals Díaz and Lerdo together got more votes than Juárez. Juárez got 5,837 electoral votes, Díaz 3,555, and Lerdo 2,874 in the 1871 general election, throwing the outcome for congress to decide.[56] The decision in congress was for Juárez since it was packed with his supporters, and opponents considered the election fraudulent.

Defeated opposition candidate Díaz issued the Plan of la Noria call to arms against Juárez. Díaz had not been involved in the many insurrections that broke out after 1867 and had it not gathered other opponents of Juárez it would have just one more insurrection. Although Juárez had lost support, many political opponents did not want civil war as a means to power. Juárez kept the loyalty of key military figures and was able to outlast the rebellion. Díaz's plan was not a compelling argument for violence. Díaz showed himself at this juncture to be a flawed political and military leader.[60] Juárez called Díaz a "latter-day Santa Anna", invoking the liberals' archenemy.[56] Juárez took the opportunity of the rebellion to attack entrenched groups within various states, using government forces to neutralize rebellious elements in state militias.[61] Having outlasted Díaz's serious rebellion, Juárez again tried to institute constitutional reform but was blocked by congress.[62]

Personal life

.jpg.webp)

On 31 October 1843, when he was in his late 30s, Juárez married Margarita Maza, the adoptive daughter of his sister's patron.[63] Margarita was 20 years younger than Juárez. Her father Antonio Maza Padilla was from Genoa and her mother Petra Parada Sigüenza was Mexican and of Spanish descent. They were part of Oaxaca's upper-class society. Margarita Maza accepted his proposal and said of Juárez, "He is very homely, but very good."[64] With his marriage to a white woman, Juárez gained social standing. Although legal racial categories were abolished shortly after independence, in social life, ethnic categories were still used. Their ethnically mixed (white/indigenous) marriage was unusual at the time, but it is not often explicitly noted in standard biographies. Their marriage lasted until Margarita's death from cancer in January 1871, when Juárez was planning his run for reelection. Juárez and Maza had ten children together, who were ethnically mixed mestizos, including twins María de Jesús and Josefa, born in 1854. Two boys and three girls died in early childhood. Two of their sons died while they were in exile in New York with their mother during the French Intervention. Their only surviving son was Benito Juárez Maza, b. 29 October 1852, was a diplomat and politician, and Governor of Oaxaca 1911–12; he married but had no children.[65] Juárez's daughter Manuela married Cuban poet and separatist Pedro Santacilia in May 1863.[24]

Juárez wrote only briefly about his indigenous heritage, in Apuntes para mis hijos, describing his parents as "Indians of the country's primitive race."[66] His vision of Mexico was that individual indigenous Mexicans would assimilate culturally and become full citizens of Mexico, equal before the law. "Everything that Juárez and the Liberal circle stood for militated against [his] identification" as an indigenous person.[67] According to one biographer, he "has been the object of so much mythology that it is almost impossible to uncover the facts of his life."[68]

Benito Juárez also is known to have had two other children. He had fathered a son and a daughter before he married Margarita, a son, Tereso, perhaps around 1838; and Susana. Little is known about them. One of his biographers, Charles Allen Smart, citing the work of Jorge L. Tamayo, the editor of Juárez's letters, says that Juárez's natural son might be alluded to in a letter from a certain Refugio Álvarez, an officer during the French invasion. Juárez's son was taken prisoner by conservative general Tomás Mejía when the conservatives captured San Luis Potosí in December 1863. Juárez's two sons with Margarita Maza were minors at the time and the third not yet born, so the conclusion is that the letter refers to Tereso. In his research for the biography, Smart found no explicit references to Tereso.[69] Juárez's daughter Susana was mentioned by Tamayo, and Smart includes that information, but without page citations to Tamayo's publication. Susana was said to have become an invalid and a narcotics addict who was cared for by Juárez's friends Sr. Miguel Castro and his wife when Castro was governor of Oaxaca.[70] The natural children's mother died before Juárez married Margarita, when Susana was three years old. Juárez and his wife formally adopted Susana, who never married and was with her adoptive mother at her death.[63][71] Margarita Maza de Juárez was buried in the Juárez mausoleum in Mexico City.

Juárez was a 33rd Scottish Rite Freemason[72] and a member of the directive of the Mexican brotherhood. He was initiated under the name of Guglielmo Tell.[73][74][75]

Juárez's health suffered in 1870, but he recovered. His wife Margarita died in 1871 and his health began to fail in 1872. He suffered a heart attack in March 1872, the day before his birthday. He suffered another attack on July 8 and a fatal attack on 17 July.[76]

Freemasonry

Juárez was initiated into Freemasonry in the York Rite in Oaxaca. He then moved to the Mexican National Rite, where he ascended to the highest degree, the ninth, which is equivalent to the 33rd degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite. The York Rite was of more liberal and republican ideas with respect to the Scottish Rite that also existed in Mexico, which was of centralist political ideas. The Mexican National Rite emerged from a group of Yorkist Masons and another group of Scottish Masons whose common objective was to gain independence from foreigners and promote a nationalist mentality.[77][78]

Juárez was fervent in Masonic practice. His name is held in veneration in many rites. Many lodges and philosophical bodies have adopted him as a sacred symbol.[79][80][81]

Juárez's initiation ceremony was attended by distinguished Masons, such as Manuel Crescencio Rejon, author of the Yucatán Constitution of 1840; Valentin Gomez Farias, President of Mexico; Pedro Zubieta, General Commander in the Federal District and the State of Mexico; Congressman Fernando Ortega; Congressman Tiburcio Cañas; Congressman Francisco Banuet; Congressman Agustin Buenrostro; Congressman Joaquin Navarro and Congressman Miguel Lerdo de Tejada. After the proclamation, the apprentice mason Juárez adopted the symbolic name of Guillermo Tell.[82][83]

Death

Juárez died of a heart attack on 18 July 1872, aged 66. He had been ill for two days, seemingly without alarming symptoms, but he appears to have suffered an attack similar to the one in October 1870. "At daybreak on the morning of the 19th [of July] the inhabitants of this capital were startled by the roar of artillery, followed by a gun [shot] each quarter of an hour, which indicated the death of the head of the government.[84] A death mask was made and Juárez was given a state funeral. He is buried in the Panteón de San Fernando, where other Mexican notables are interred. There is an account in Ralph Roeder's 1947 lengthy biography of Juárez about his death,[85] but although the work has many direct quotations from sources, it is flawed because there are no scholarly citations.

When Juárez died, Díaz's reasons for rebellion – fraudulent elections, presidential coercion of states – no longer existed. He was succeeded by Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, the head of the Supreme Court. Díaz was amnestied for his rebellion by Lerdo in November 1872.[65] Díaz later rebelled against Lerdo in 1876. Although Díaz was a rival of Juárez during his life, after Díaz seized power he helped shape the historical memory of Juárez.

Legacy

Today Benito Juárez is remembered as being a progressive reformer dedicated to democracy, equal rights for his nation's indigenous peoples, reduction in the power of organized religion, especially the Catholic Church, and a defense of national sovereignty. The period of his leadership is known in Mexican history as La Reforma del Norte (The Reform of the North). It constituted a liberal political and social revolution with major institutional consequences: the expropriation of church lands, the subordination of the army to civilian control, liquidation of peasant communal land holdings, the separation of church and state in public affairs, and the disenfranchisement of bishops, priests, nuns and lay brothers, codified in the "Juárez Law" or "Ley Juárez".[86]

La Reforma represented the triumph of Mexico's liberal, federalist, anti-clerical, and pro-capitalist forces over the conservative, centralist, corporatist, and theocratic elements that sought to reconstitute a locally run version of the colonial era. It replaced a semi-feudal social system with a more market-driven one. But, following Juárez's death, the lack of adequate democratic and institutional stability soon resulted in a return to centralized autocracy and economic exploitation under the regime of Porfirio Díaz. The Porfiriato (1876–1911), in turn, collapsed at the beginning of the Mexican Revolution.

Honors and recognition

Honors in his lifetime

- On 7 February 1866, Juárez was elected as a companion of the 3rd class of the Pennsylvania Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS). While membership in MOLLUS was normally limited to Union officers who had served during the American Civil War and their descendants, members of the 3rd Class were civilians who had made a significant contribution to the Union war effort. Juárez is one of the very few non-United States citizens to be a MOLLUS companion.

- On 11 May 1867, the Congress of the Dominican Republic proclaimed Juárez the Benemérito de la América (Distinguished of America).[87]

- On 16 July 1867, the government of Peru recognized Juárez's accomplishments and on 28 July of the same year the School of Medicine of San Fernando, Perú, issued a gold medal to honor him; the medal can be seen at the Museo Nacional de Historia.[87]

Place names

- Numerous cities, towns, streets, and institutions in Mexico are named after Benito Juárez, including the former El Paso del Norte, now called Ciudad Juárez; see Juárez (disambiguation) for a partial list.

- Mexico City International Airport is better known in Mexico by its first official name Aeropuerto Internacional Benito Juárez, or internationally often as Mexico City Juárez.

- The Benito Juárez Partido in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, and the city of Benito Juárez, Buenos Aires are both named after Juárez, as a gesture of friendship between Argentina and Mexico.

- Benito Juárez Marg (marg means road in Sanskrit/Hindi) is a major road in South Delhi, India.

Mexican currency

- Juárez is depicted on the 20-peso banknote. From the time of Juárez, Mexico's government has issued several notes with the face and the subject of Juárez. In 2000, $20.00 (twenty pesos) bills were issued: on one side is the bust of Juárez and to his left, the Juarista eagle across the Chamber. In 2018, new $500.00 (five hundred pesos) bills were released, also featuring the bust of Juárez. A caption directly below this says in Spanish, "President Benito Juárez, promoter of the Laws of Reform, during his triumphant entrance to Mexico City on 13 July 1867, symbolizing the restoration of the Republic". Juárez appears to face a depiction of his entrance into Mexico City. His likeness appears on two bills simultaneously, and while both are blue in color, the 500-peso and 20-peso notes differ in size and texture.[88]

Monuments and statuary

Benito Juárez is notable for the number of statues and monuments in his honor outside of Mexico.

- In Washington, D.C. is a monument of Juárez by Enrique Alciati, a gift to the US from Mexico.[89]

- The sculptor Julian Martinez dedicated two works to Juárez, a full sculpture in Chicago[90] and a bust in Houston.[91]

- In New York City is Benito Juárez (2004), a sculpture by Mexican Moises Cabrera Orozco, installed in Bryant Park in Manhattan.[92]

- Statue of Benito Juárez (San Diego)

- Statue of Benito Juárez in New Orleans

Film and media

- Franz Werfel wrote the play Juárez and Maximilian which was presented at Berlin in 1924, directed by Max Reinhardt.

- Juárez has been mentioned or featured in television and film. Juárez is a 1939 American historical drama film directed by William Dieterle, and starring Paul Muni as Juárez.

- Carleton Young portrayed Juárez in Zorro's Fighting Legion (1939)

- In January 1959, the episode entitled "The Desperadoes" of the ABC/Warner Brothers western television series, Sugarfoot, starring Will Hutchins in the title role, focuses upon an imaginary plot to assassinate Juárez. Set at a mission in South Texas, the episode features Anthony George as a Catholic priest, Father John, a friend of the series character Tom "Sugarfoot" Brewster.[93]

- The actor Jan Arvan (1913–1979) was cast as President Juárez in the 1959 episode, "A Town Is Born" on the syndicated television anthology series, Death Valley Days, hosted by Stanley Andrews. Than Wyenn played Isaacs, a storekeeper in Nogales, Arizona Territory, who hides gold for the Mexican government in the fight against Maximilian. Jean Howell played his wife, Ruth Isaacs.[94]

- Frank Sorello (1929–2013) portrayed Juárez in two episodes of Robert Conrad's The Wild Wild West, an American espionage adventure television program: "The Night of the Eccentrics" (1966), and "The Night of the Assassin" (1967).

- Juárez is a character in Harry Harrison's alternate history novels the Stars and Stripes trilogy

Other eponyms

- The Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was named after Juárez.[95]

- In Sofia, Bulgaria, the municipal school Primary school Nr. 49 is named after Juárez.

- In Warsaw, Poland, the public school Szkoła Podstawowa Nr. 85 im. Benito Juáreza w Warszawie is named after Juárez.

- Juárez is commemorated in the scientific name of a species of Mexican snake, Geophis Juárezi.[96]

Juárez Complex National Palace

In the National Palace in Mexico City, where he lived while in power, there is a small museum in his honor. It contains his furniture and personal effects.

|

|

|

|---|

Quotes

Juárez's quote continues to be well-remembered in Mexico: "Entre los individuos, como entre las naciones, el respeto al derecho ajeno es la paz", meaning "Among individuals, as among nations, respect for the rights of others is peace". The portion of this motto in bold is inscribed on the coat of arms of Oaxaca. A portion is inscribed on the Juárez statue in Bryant Park in New York City, "Respect for the rights of others is peace." This quote summarizes Mexico's stances toward foreign affairs.

Another notable quote: "La ley ha sido siempre mi espada y mi escudo", or "The law has always been my shield and my sword", is a phrase often displayed inside court and tribunals buildings.[97]

See also

- List of heads of state of Mexico

- José María Jesús Carbajal Supporter of Juárez

- History of Mexico

- Statues of the Liberators

- Liberalism in Mexico

- War of the Reform

- Reform laws

- History of Roman Catholicism in Mexico

Further reading

- Cadenhead, Ivie E., Jr. Benito Juárez. 1973.

- Hamnett, Brian. "Benito Juárez", in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997

- Hamnett, Brian. Juárez (Profiles in Power). New York: Longmans, 1994. ISBN 978-0582050532.

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

- Olliff, Donathan C. Reform Mexico and the United States: A Search for Alternatives to Annexation, 1854–1861. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press 1981.

- Perry, Laurens Ballard. Juárez and Díaz: Machine Politics in Mexico. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press 1978. ISBN 0-87580-058-0

- Roeder, Ralph. Juárez and His Mexico: A Biographical History. 2 vols. 1947.

- Scholes, Walter V. Mexican Politics During the Juárez Regime, 1855–1872. Columbia MO: University of Missouri Press 1957.

- Sheridan, Philip H. Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan. 2 vols. New York: Charles L. Webster & Co., 1888. ISBN 1-58218-185-3.

- Sinkin, Richard N. The Mexican Reform, 1855–1876: A Study in Liberal Nation-Building. 1979.

- Smart, Charles Allen. Viva Juárez: A Biography. 1963.

- Stevens, D.F. "Benito Juárez". Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 3. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Weeks, Charles A. The Juárez Myth in Mexico. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press 1987.

References

- "Benito Juárez (March 21, 1806 – July 18, 1872)". Banco de México. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- Hamnett, Brian R. (1991). "Benito Juárez, Early Liberalism, and the Regional Politics of Oaxaca, 1828–1853". Bulletin of Latin American Research. 10 (1): 3–21. doi:10.2307/3338561. ISSN 0261-3050. JSTOR 3338561.

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power, New York: Harper Collins, 1997, p. 162.

- Stevens, "Benito Juárez", pp. 333–335.

- Hamnett, "Benito Juárez", pp. 718–721.

- Hamnett, "Benito Juárez", Encyclopedia of Mexico, 718

- Hamnett, "Benito Juárez" p. 721.

- Stevens, "Benito Juárez", 333.

- Weeks, Charles A. (1987). The Juárez myth in Mexico. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-585-26147-4. OCLC 45728281.

- Hamnett, Juárez, 238–239.

- Hamnett, Juárez, p. xii.

- Stacy, Lee, ed. (2002). Mexico and the United States. Vol. 1. Marshall Cavendish. p. 435. ISBN 978-0-7614-7402-9.

- "Juárez, Benito, on his early years". Historical Text Archive. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- "Juárez' Birthday". Sistema Internet de la Presidencia. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- Hamnett, Juárez, pp. 20–21.

- Chassen-López, From Liberal to Revolutionary Oaxaca, 252; Juárez quoted in Chassen-López, 252.

- Sinkin, Richard N. (1979). The Mexican reform, 1855-1876 : a study in liberal nation-building. Austin: The University of Texas, Institute of Latin American Studies. ISBN 0-292-75044-7. OCLC 925061668.

- Hamnett, Juárez, p. 253.

- "Benito Juárez". Who2. 2006. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- Rojas, Rafael (2008). "Los amigos cubanos de Juárez" (PDF). Istor: Revista de historia internacional: 42–57 – via Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas.

- Olliff, Donathon C. Reforma Mexico and the United States: A Search for Alternatives to Annexation, 1854–1861. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press 1981, 4

- "Juárez, Benito". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 2007.

- Lipsitz, George (2006). The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics (2nd ed.). Temple University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-59213-494-6.

benito juarez new orleans cigar.

- Hamnett, Juárez, 51

- Agencia Seméxico (21 March 2015). "Margarita a Maza de Juárez: Mucho más que una esposa (Margarita to Maza de Juárez: Much more than a wife)". Pagina 3. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Jan Bazant, "From Independence to the Liberal Republic, 1821–1867" in Mexico Since Independence, Leslie Bethell, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press 1991, p. 32.

- Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2007, pp. 335–343.

- Hamnett, Juárez, 51–53

- Thomson, Guy P. C. (1991). "Popular Aspects of Liberalism in Mexico, 1848-1888". Bulletin of Latin American Research. 10 (3): 265–292. doi:10.2307/3338671. ISSN 0261-3050. JSTOR 3338671.

- Stevens, "Benito Juárez", p. 334.

- Scholes, Mexican Politics During the Juárez Regime, 23

- Vanderwood, Paul; Weis, Robert (24 May 2018). "The Reforma Period in Mexico". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.581. ISBN 978-0-19-936643-9. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Mexico: An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Culture and History. Denver, Colorado; Oxford, England: abc-clio. 2004. pp. 245–246. ISBN 978-1576071328.

- Burke, Ulick Ralph (1894). A Life of Benito Juarez: Constitutional President of Mexico. London and Sydney: Remington and Company. pp. 94–96.

- Hamnett, Brian R. A Concise History of Mexico. Cambridge. p. 16.

- Scholes, Mexican Politics During the Juárez Regime, 67–70

- Scholes, Mexican Politics During the Juárez Regime, 71–72

- Hamnett, Juárez, 255–256

- Knight, Alan (1986). The Mexican Revolution. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0-521-24475-7. OCLC 12135091.

- Vanderwood, Paul J. Disorder and Progress: Bandits, Police, and Mexican Development. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1981, pp. 46–50.

- Roeder, Juárez and his Mexico, 294

- Hamnett, Juárez, 154, 157, 256.

- Gille, Geneviève (1998), Ludlow, Leonor; Marichal, Carlos (eds.), "Los capitales franceses y la expedición a México", Un siglo de deuda pública en México (First ed.), El Colegio de Mexico, pp. 125–151, ISBN 978-968-6914-90-0, retrieved 25 September 2022

- Scholes, Mexican Politics during the Juárez Regime, 78–79

- Scholes, Mexican Politics during the Juárez Regime, 85–86

- Hamnett, Juárez, 256

- Hamnett, Juárez, 256–257

- I.E. Cadenhead, "González Ortega and the Presidency of Mexico." Hispanic American Historical Review, XXXII, No. 331–346

- Scholes, Walter. Mexican Politics During the Juárez Regime, 113–115

- Scholes, Mexican Politics During the Juárez Regime, 79

- Gordon, Leonard (1968). "Lincoln and Juarez-A Brief Reassessment of Their Relationship". Hispanic American Historical Review. 48 (1): 75–80. doi:10.2307/2511401. JSTOR 2511401.

- (General Philip Sheridan wrote in his journal about how he "misplaced" about 30,000 muskets). Mexico's Lincoln: The Ecstasy and Agony of Benito Juarez

- Sheridan, p. 405.

- Partyka, Donald (25 January 2022). "Long View: When An Austrian Archduke Became Emperor of Mexico". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Hamnett, Brian (1996). "Liberalism Divided: Regional Polities and the National Project During the Mexican Restored Republic, 1867–1876". Hispanic American Historical Review. 76 (4): 659–689. doi:10.1215/00182168-76.4.659 – via Duke University Press.

- Hamnett, "Benito Juárez", 720

- Hamnett, Juárez, 202–204

- Perry, Laurens Ballard. Juárez and Díaz: Machine Politics in Mexico. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press 1978, 353–354

- Perry, Juárez and Díaz, 33

- Perry, Juárez and Díaz, 165–174

- Hamnett, Juárez, 221–222

- Hamnett, "Benito Juárez", 270

- "Los Hijos de Benito Juárez / 571 | Sin Censura".

- Ralph Roeder, Juárez and His Mexico, New York: The Viking Press, 1947, pp. 66–67.

- Hamnett, Juárez, 234

- Juárez, Benito, Apuntes para mis hijos, Mexico: Red ediciones 2014, 9

- Hamnett, Brian. Juárez, New York: Longman 1994, 35, 51

- Hamnett, Brian, "Benito Juárez", Encyclopedia of Mexico, 1997, p. 718.

- Smart, Charles Allen. Viva Juárez: A Biography. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company 1963, 297–298

- Smart, Viva Juárez, 68.

- Hamnett, Juárez, p. 234.

- Giordano Gamberini (1975). Mille volti di massoni. Grande Oriente d'Italia (in Italian). Rome: Erasmo. p. 253. LCCN 75535930. OCLC 3028931.

- Q.H. Cuauhtémoc; D. Molina García. "Benito Juárez y el pensamiento masónico". Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry.

- Eugen Lennhof; Oskar Posner; Dieter Binder (2006). Internationales FreimaurerLexikon (in German). Herbig. ISBN 978-3-7766-2478-6. OCLC 1041262501.

- D. Molina García, Benito Juárez y el pensamiento masónico. Cuauhtémoc.

- Hamnett, Juárez. 234

- "Benito Juárez, el admirado y denostado primer presidente indígena de México (y qué papel jugó en la modernización)". BBC News Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "Masonería, una sociedad secreta en México". México Desconocido (in Spanish). 29 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "BENITO JUÁREZ Y EL PENSAMIENTO MASÓNICO". www.freemasons-freemasonry.com. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- Losser, Sheryl (8 June 2022). "Is Freemasonry's role in Mexican history a secret in plain sight?". Mexico News Daily. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- Fernando Reyes | El Heraldo de Chihuahua. "Conmemoran masones el natalicio de Benito Juárez". El Heraldo de Chihuahua | Noticias Locales, Policiacas, de México, Chihuahua y el Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "¿Benito Juárez era masón? Esto responde AMLO". Publimetro México (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "17 datos de Benito Juárez que no te enseñan en la escuela". ADNPolítico (in Spanish). 17 March 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- Mexican Dispatches, July 24, 1872, vol. 46, quoted in Scholes, Mexican Politics During the Juárez Regime, 176.

- Roeder, Juárez and His Mexico, 725–726

- "La ley Juárez, de 23 de noviembre de 1855" (PDF).

- Morgado, Jorge Rodríguez y. "El Benemérito de las Américas". www.sabersinfin.com. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- "Benito Juárez, gray whale grace new 500-peso banknote". 27 August 2018.

- Smithsonian Institution (1993). "Benito Juarez (sculpture)". Save Outdoor Sculpture, District of Columbia survey. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Benito Pablo Juárez". The Magnificent Mile. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Benito Juarez". www.houstontx.gov. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Bryant Park Monuments – Benito Juarez : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "The Desperadoes on Death Valley Days". tv.com. 6 January 1959. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- "A Town is Born on Death Valley Days". IMDb. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Living History 2; Chapter 2: Italy under Fascism – ISBN 1-84536-028-1

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Juarez, B.", p. 137).

- Brunet-Jailly, Emmanuel (2015). Border Disputes: A Global Encyclopedia [3 volumes]: A Global Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 363. ISBN 978-1610690249.

External links

- Mexico's Lincoln: The Ecstasy and Agony of Benito Juárez

- Historical Text Archive: Juárez, Benito, on La Reforma

- Timeline

- Juárez Photos – Planeta.com