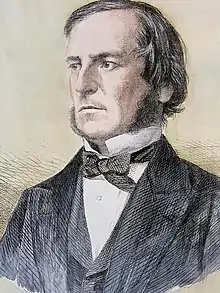

George Boole

George Boole (/buːl/; 2 November 1815 – 8 December 1864) was a largely self-taught English mathematician, philosopher, and logician, most of whose short career was spent as the first professor of mathematics at Queen's College, Cork in Ireland. He worked in the fields of differential equations and algebraic logic, and is best known as the author of The Laws of Thought (1854) which contains Boolean algebra. Boolean logic is credited with laying the foundations for the Information Age.[4]

George Boole | |

|---|---|

Boole, c. 1860 | |

| Born | 2 November 1815 Lincoln, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 8 December 1864 (aged 49) Ballintemple, Cork, Ireland |

| Education | Bainbridge's Commercial Academy[1] |

| Spouse | Mary Everest Boole |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | British algebraic logic[2] |

| Institutions | Lincoln Mechanics' Institute[3] Free School Lane, Lincoln University College Cork |

Main interests | Mathematics, logic, philosophy of mathematics |

Notable ideas | Abstract algebraic logic Boolean algebra Boolean function Boolean polynomials Boolean ring Boole's expansion theorem Boole's inequality Boole's rule Boole's syllogistic Boole–Fréchet inequalities Euler–Boole summation Imprecise probability Invariant theory Wholistic reference |

Boole maintained that:

No general method for the solution of questions in the theory of probabilities can be established which does not explicitly recognise, not only the special numerical bases of the science, but also those universal laws of thought which are the basis of all reasoning, and which, whatever they may be as to their essence, are at least mathematical as to their form.[5]

Early life

Boole was born in 1815 in Lincoln, Lincolnshire, England, the son of John Boole senior (1779–1848), a shoemaker[6] and Mary Ann Joyce.[7] He had a primary school education, and received lessons from his father, but due to a serious decline in business, he had little further formal and academic teaching.[8] William Brooke, a bookseller in Lincoln, may have helped him with Latin, which he may also have learned at the school of Thomas Bainbridge. He was self-taught in modern languages.[3] In fact, when a local newspaper printed his translation of a Latin poem, a scholar accused him of plagiarism under the pretence that he was not capable of such achievements.[9] At age 16, Boole became the breadwinner for his parents and three younger siblings, taking up a junior teaching position in Doncaster at Heigham's School.[10] He taught briefly in Liverpool.[1]

Boole participated in the Lincoln Mechanics' Institute, in the Greyfriars, Lincoln, which was founded in 1833.[3][11] Edward Bromhead, who knew John Boole through the institution, helped George Boole with mathematics books[12] and he was given the calculus text of Sylvestre François Lacroix by the Rev. George Stevens Dickson of St Swithin's, Lincoln.[13] Without a teacher, it took him many years to master calculus.[1]

At age 19, Boole successfully established his own school in Lincoln: Free School Lane.[14] Four years later he took over Hall's Academy in Waddington, outside Lincoln, following the death of Robert Hall. In 1840, he moved back to Lincoln, where he ran a boarding school.[1] Boole immediately became involved in the Lincoln Topographical Society, serving as a member of the committee, and presenting a paper entitled "On the origin, progress, and tendencies of polytheism", especially amongst the ancient Egyptians and Persians, and in modern India.[15]

Boole became a prominent local figure, an admirer of John Kaye, the bishop.[16] He took part in the local campaign for early closing.[3] With Edmund Larken and others he set up a building society in 1847.[17] He associated also with the Chartist Thomas Cooper, whose wife was a relation.[18]

From 1838 onwards, Boole was making contacts with sympathetic British academic mathematicians and reading more widely. He studied algebra in the form of symbolic methods, as far as these were understood at the time, and began to publish research papers.[1]

Professorship and Life in Cork

Boole's status as a mathematician was recognised by his appointment in 1849 as the first professor of mathematics at Queen's College, Cork (now University College Cork (UCC)) in Ireland. He met his future wife, Mary Everest, there in 1850 while she was visiting her uncle John Ryall who was professor of Greek. They married some years later in 1855.[19][20] He maintained his ties with Lincoln, working there with E. R. Larken in a campaign to reduce prostitution.[21]

Honours and awards

In 1844, Boole's paper "On a General Method in Analysis" won the first gold prize for mathematics awarded by the Royal Society.[22] He was awarded the Keith Medal by the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1855[23] and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1857.[13] He received honorary degrees of LL.D. from the University of Dublin and the University of Oxford.[24]

.jpg.webp)

Works

Boole's first published paper was "Researches in the theory of analytical transformations, with a special application to the reduction of the general equation of the second order", printed in the Cambridge Mathematical Journal in February 1840 (Volume 2, No. 8, pp. 64–73), and it led to a friendship between Boole and Duncan Farquharson Gregory, the editor of the journal.[19] His works are in about 50 articles and a few separate publications.[26][21]

In 1841, Boole published an influential paper in early invariant theory.[13] He received a medal from the Royal Society for his memoir of 1844, "On a General Method in Analysis". It was a contribution to the theory of linear differential equations, moving from the case of constant coefficients on which he had already published, to variable coefficients.[27] The innovation in operational methods is to admit that operations may not commute.[28] In 1847, Boole published The Mathematical Analysis of Logic, the first of his works on symbolic logic.[29]

Differential equations

Boole completed two systematic treatises on mathematical subjects during his lifetime. The Treatise on Differential Equations[30] appeared in 1859, and was followed, the next year, by a Treatise on the Calculus of Finite Differences,[31] a sequel to the former work.

Analysis

In 1857, Boole published the treatise "On the Comparison of Transcendent, with Certain Applications to the Theory of Definite Integrals",[32] in which he studied the sum of residues of a rational function. Among other results, he proved what is now called Boole's identity:

for any real numbers ak > 0, bk, and t > 0.[33] Generalisations of this identity play an important role in the theory of the Hilbert transform.[33]

Symbolic logic

In 1847, Boole published the pamphlet Mathematical Analysis of Logic. He later regarded it as a flawed exposition of his logical system and wanted An Investigation of the Laws of Thought on Which are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities to be seen as the mature statement of his views. Contrary to widespread belief, Boole never intended to criticise or disagree with the main principles of Aristotle's logic. Rather he intended to systematise it, to provide it with a foundation, and to extend its range of applicability.[34] Boole's initial involvement in logic was prompted by a current debate on quantification, between Sir William Hamilton who supported the theory of "quantification of the predicate", and Boole's supporter Augustus De Morgan who advanced a version of De Morgan duality, as it is now called. Boole's approach was ultimately much further reaching than either sides' in the controversy.[35] It founded what was first known as the "algebra of logic" tradition.[36]

Among his many innovations is his principle of wholistic reference, which was later, and probably independently, adopted by Gottlob Frege and by logicians who subscribe to standard first-order logic. A 2003 article[37] provides a systematic comparison and critical evaluation of Aristotelian logic and Boolean logic; it also reveals the centrality of holistic reference in Boole's philosophy of logic.

1854 definition of the universe of discourse

In every discourse, whether of the mind conversing with its own thoughts, or of the individual in his intercourse with others, there is an assumed or expressed limit within which the subjects of its operation are confined. The most unfettered discourse is that in which the words we use are understood in the widest possible application, and for them, the limits of discourse are co-extensive with those of the universe itself. But more usually we confine ourselves to a less spacious field. Sometimes, in discoursing of men we imply (without expressing the limitation) that it is of men only under certain circumstances and conditions that we speak, as of civilised men, or of men in the vigour of life, or of men under some other condition or relation. Now, whatever may be the extent of the field within which all the objects of our discourse are found, that field may properly be termed the universe of discourse. Furthermore, this universe of discourse is in the strictest sense the ultimate subject of the discourse.[38]

Treatment of addition in logic

Boole conceived of "elective symbols" of his kind as an algebraic structure. But this general concept was not available to him: he did not have the segregation standard in abstract algebra of postulated (axiomatic) properties of operations, and deduced properties.[39] His work was a beginning to the algebra of sets, again not a concept available to Boole as a familiar model. His pioneering efforts encountered specific difficulties, and the treatment of addition was an obvious difficulty in the early days.

Boole replaced the operation of multiplication by the word "and" and addition by the word "or". But in Boole's original system, + was a partial operation: in the language of set theory it would correspond only to disjoint union of subsets. Later authors changed the interpretation, commonly reading it as exclusive or, or in set theory terms symmetric difference; this step means that addition is always defined.[36][40]

In fact, there is the other possibility, that + should be read as disjunction.[39] This other possibility extends from the disjoint union case, where exclusive or and non-exclusive or both give the same answer. Handling this ambiguity was an early problem of the theory, reflecting the modern use of both Boolean rings and Boolean algebras (which are simply different aspects of one type of structure). Boole and Jevons struggled over just this issue in 1863, in the form of the correct evaluation of x + x. Jevons argued for the result x, which is correct for + as disjunction. Boole kept the result as something undefined. He argued against the result 0, which is correct for exclusive or, because he saw the equation x + x = 0 as implying x = 0, a false analogy with ordinary algebra.[13]

Probability theory

The second part of the Laws of Thought contained a corresponding attempt to discover a general method in probabilities. Here the goal was algorithmic: from the given probabilities of any system of events, to determine the consequent probability of any other event logically connected with those events.[41]

Death

In late November 1864, Boole walked, in heavy rain, from his home at Lichfield Cottage in Ballintemple[42] to the university, a distance of three miles, and lectured wearing his wet clothes.[43] He soon became ill, developing pneumonia. As his wife believed that remedies should resemble their cause, she wrapped him in wet blankets – the wet having brought on his illness.[43][44][45] Boole's condition worsened and on 8 December 1864,[46] he died of fever-induced pleural effusion.

He was buried in the Church of Ireland cemetery of St Michael's, Church Road, Blackrock (a suburb of Cork). There is a commemorative plaque inside the adjoining church.[47]

Legacy

_(2).jpg.webp)

Boole is the namesake of the branch of algebra known as Boolean algebra, as well as the namesake of the lunar crater Boole. The keyword Bool represents a Boolean datatype in many programming languages, though Pascal and Java, among others, both use the full name Boolean.[48] The library, underground lecture theatre complex and the Boole Centre for Research in Informatics[49] at University College Cork are named in his honour. A road called Boole Heights in Bracknell, Berkshire is named after him.

19th-century development

Boole's work was extended and refined by a number of writers, beginning with William Stanley Jevons. Augustus De Morgan had worked on the logic of relations, and Charles Sanders Peirce integrated his work with Boole's during the 1870s.[50] Other significant figures were Platon Sergeevich Poretskii, and William Ernest Johnson. The conception of a Boolean algebra structure on equivalent statements of a propositional calculus is credited to Hugh MacColl (1877), in work surveyed 15 years later by Johnson.[50] Surveys of these developments were published by Ernst Schröder, Louis Couturat, and Clarence Irving Lewis.

20th-century development

In 1921, the economist John Maynard Keynes published a book on probability theory, A Treatise of Probability. Keynes believed that Boole had made a fundamental error in his definition of independence which vitiated much of his analysis.[51] In his book The Last Challenge Problem, David Miller provides a general method in accord with Boole's system and attempts to solve the problems recognised earlier by Keynes and others. Theodore Hailperin showed much earlier that Boole had used the correct mathematical definition of independence in his worked out problems.[52]

Boole's work and that of later logicians initially appeared to have no engineering uses. Claude Shannon attended a philosophy class at the University of Michigan which introduced him to Boole's studies. Shannon recognised that Boole's work could form the basis of mechanisms and processes in the real world and that it was therefore highly relevant. In 1937 Shannon went on to write a master's thesis, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in which he showed how Boolean algebra could optimise the design of systems of electromechanical relays then used in telephone routing switches. He also proved that circuits with relays could solve Boolean algebra problems. Employing the properties of electrical switches to process logic is the basic concept that underlies all modern electronic digital computers. Victor Shestakov at Moscow State University (1907–1987) proposed a theory of electric switches based on Boolean logic even earlier than Claude Shannon in 1935 on the testimony of Soviet logicians and mathematicians Sofya Yanovskaya, Gaaze-Rapoport, Roland Dobrushin, Lupanov, Medvedev and Uspensky, though they presented their academic theses in the same year, 1938. But the first publication of Shestakov's result took place only in 1941 (in Russian). Hence, Boolean algebra became the foundation of practical digital circuit design; and Boole, via Shannon and Shestakov, provided the theoretical grounding for the Information Age.[53]

21st-century celebration

"Boole's legacy surrounds us everywhere, in the computers, information storage and retrieval, electronic circuits and controls that support life, learning and communications in the 21st century. His pivotal advances in mathematics, logic and probability provided the essential groundwork for modern mathematics, microelectronic engineering and computer science."

—University College Cork.[4]

The year 2015 saw the 200th anniversary of Boole's birth. To mark the bicentenary year, University College Cork joined admirers of Boole around the world to celebrate his life and legacy.

UCC's George Boole 200[54] project, featured events, student outreach activities and academic conferences on Boole's legacy in the digital age, including a new edition of Desmond MacHale's 1985 biography The Life and Work of George Boole: A Prelude to the Digital Age,[55] 2014).

The search engine Google marked the 200th anniversary of his birth on 2 November 2015 with an algebraic reimaging of its Google Doodle.[4]

Views

Boole's views were given in four published addresses: The Genius of Sir Isaac Newton; The Right Use of Leisure; The Claims of Science; and The Social Aspect of Intellectual Culture.[56] The first of these was from 1835 when Charles Anderson-Pelham, 1st Earl of Yarborough gave a bust of Newton to the Mechanics' Institute in Lincoln.[57] The second justified and celebrated in 1847 the outcome of the successful campaign for early closing in Lincoln, headed by Alexander Leslie-Melville, of Branston Hall.[58] The Claims of Science was given in 1851 at Queen's College, Cork.[59] The Social Aspect of Intellectual Culture was also given in Cork, in 1855 to the Cuvierian Society.[60]

Though his biographer Des MacHale describes Boole as an "agnostic deist",[61][62] Boole read a wide variety of Christian theology. Combining his interests in mathematics and theology, he compared the Christian trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost with the three dimensions of space, and was attracted to the Hebrew conception of God as an absolute unity. Boole considered converting to Judaism but in the end was said to have chosen Unitarianism.[reference?] Boole came to speak against what he saw as "prideful" scepticism, and instead favoured the belief in a "Supreme Intelligent Cause".[63] He also declared "I firmly believe, for the accomplishment of a purpose of the Divine Mind."[64][65] In addition, he stated that he perceived "teeming evidences of surrounding design" and concluded that "the course of this world is not abandoned to chance and inexorable fate."[66][67]

Two influences on Boole were later claimed by his wife, Mary Everest Boole: a universal mysticism tempered by Jewish thought, and Indian logic.[68] Mary Boole stated that an adolescent mystical experience provided for his life's work:

My husband told me that when he was a lad of seventeen a thought struck him suddenly, which became the foundation of all his future discoveries. It was a flash of psychological insight into the conditions under which a mind most readily accumulates knowledge [...] For a few years he supposed himself to be convinced of the truth of "the Bible" as a whole, and even intended to take orders as a clergyman of the English Church. But by the help of a learned Jew in Lincoln he found out the true nature of the discovery which had dawned on him. This was that man's mind works by means of some mechanism which "functions normally towards Monism."[69]

In Ch. 13 of Laws of Thought Boole used examples of propositions from Baruch Spinoza and Samuel Clarke. The work contains some remarks on the relationship of logic to religion, but they are slight and cryptic.[70] Boole was apparently disconcerted at the book's reception just as a mathematical toolset:

George afterwards learned, to his great joy, that the same conception of the basis of Logic was held by Leibniz, the contemporary of Newton. De Morgan, of course, understood the formula in its true sense; he was Boole's collaborator all along. Herbert Spencer, Jowett, and Robert Leslie Ellis understood, I feel sure; and a few others, but nearly all the logicians and mathematicians ignored [953] the statement that the book was meant to throw light on the nature of the human mind; and treated the formula entirely as a wonderful new method of reducing to logical order masses of evidence about external fact.[69]

Mary Boole claimed that there was profound influence – via her uncle George Everest – of Indian thought in general and Indian logic, in particular, on George Boole, as well as on Augustus De Morgan and Charles Babbage:[71]

Think what must have been the effect of the intense Hinduizing of three such men as Babbage, De Morgan, and George Boole on the mathematical atmosphere of 1830–65. What share had it in generating the Vector Analysis and the mathematics by which investigations in physical science are now conducted?[69]

Family

In 1855, Boole married Mary Everest (niece of George Everest), who later wrote several educational works on her husband's principles.

The Booles had five daughters:

- Mary Ellen (1856–1908)[72] who married the mathematician and author Charles Howard Hinton and had four children: George (1882–1943), Eric (*1884), William (1886–1909)[73] and Sebastian (1887–1923), inventor of the Jungle gym. After the sudden death of her husband, Mary Ellen committed suicide in Washington, D.C. in May 1908.[74] Sebastian had three children:

- Jean Hinton (married name Rosner) (1917–2002), a peace activist.

- William H. Hinton (1919–2004) visited China in the 1930s and 40s and wrote an influential account of the Communist land reform.

- Joan Hinton (1921–2010) worked for the Manhattan Project and lived in China from 1948 until her death on 8 June 2010; she was married to Sid Engst.

- Margaret (1858–1935), married Edward Ingram Taylor, an artist.

- Their elder son Geoffrey Ingram Taylor became a mathematician and a Fellow of the Royal Society.

- Their younger son Julian Taylor was a professor of surgery.

- Alicia (1860–1940), who made important contributions to four-dimensional geometry.

- Her son Leonard Stott, a medical doctor and tuberculosis pioneer, invented a portable X-ray machine, a pneumothorax apparatus, and system of navigation based on spherical coordinates.[75]

- Lucy Everest (1862–1904), who was the first female professor of chemistry in England.

- Ethel Lilian (1864–1960), who married the Polish scientist and revolutionary Wilfrid Michael Voynich and was the author of the novel The Gadfly.

See also

Concepts

- Boolean algebra, a logical calculus of truth values or set membership

- Boolean algebra (structure), a set with operations resembling logical ones

- Boolean circuit, a mathematical model for digital logical circuits.

- Boolean data type is a data type, having two values (usually denoted true and false)

- Boolean expression, an expression in a programming language that produces a Boolean value when evaluated

- Boolean function, a function that determines Boolean values or operators

- Boolean model (probability theory), a model in stochastic geometry

- Boolean network, a certain network consisting of a set of Boolean variables whose state is determined by other variables in the network

- Boolean processor, a 1-bit variables computing unit

- Boolean ring, a ring consisting of idempotent elements

- Boolean satisfiability problem

- Boole's syllogistic is a logic invented by 19th-century British mathematician George Boole, which attempts to incorporate the "empty set".

- Laws of thought

- Principle of wholistic reference

Other

- List of Boolean algebra topics

- List of pioneers in computer science

Notes

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "George Boole", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- Ivor Grattan-Guinness (ed.), Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences, Routledge, 2002, ch. 5.1.

- Hill, p. 149; Google Books Archived 17 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Who is George Boole: the mathematician behind the Google doodle". Sydney Morning Herald. 2 November 2015. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Boole, George (2012) [Originally published by Watts & Co., London, in 1952]. Rhees, Rush (ed.). Studies in Logic and Probability (Reprint ed.). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-486-48826-4. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- "John Boole". Lincoln Boole Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- "George Boole's Family Tree". Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- C., Bruno, Leonard (2003) [1999]. Math and mathematicians : the history of math discoveries around the world. Baker, Lawrence W. Detroit, Mich.: U X L. pp. 49. ISBN 0787638137. OCLC 41497065.

- C., Bruno, Leonard (2003) [1999]. Math and mathematicians : the history of math discoveries around the world. Baker, Lawrence W. Detroit, Mich.: U X L. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0787638137. OCLC 41497065.

- Rhees, Rush. (1954) "George Boole as Student and Teacher. By Some of His Friends and Pupils", Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences. Vol. 57. Royal Irish Academy

- "Society for the History of Astronomy, Lincolnshire". Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Edwards, A. W. F. "Bromhead, Sir Edward Thomas French". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37224. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Burris, Stanley. "George Boole". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- George Boole: Self-Education & Early Career Archived 22 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine University College Cork

- A Selection of Papers relative to the County of Lincoln, read before the Lincolnshire Topographical Society, 1841–1842. Printed by W. and B. Brooke, High-Street, Lincoln, 1843.

- Hill, p. 172 note 2; Google Books Archived 10 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Hill, p. 130 note 1; Google Books Archived 27 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Hill, p. 148; Google Books Archived 4 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 235.

- Ronald Calinger, Vita mathematica: historical research and integration with teaching (1996), p. 292; Google Books Archived 27 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Hill, p. 138 note 4; Google Books Archived 27 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- MacHale, Desmond. The Life and Work of George Boole: A Prelude to the Digital Age. p. 97.

- "Keith Awards 1827–1890". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Cambridge Journals Online. 36 (3): 767–770. doi:10.1017/S0080456800037984. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Ivor Grattan-Guinness, Gérard Bornet, George Boole: Selected manuscripts on logic and its philosophy (1997), p. xiv; Google Books Archived 22 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Lincoln Cathedral | Things to do". Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- A list of Boole's memoirs and papers is in the Catalogue of Scientific Memoirs published by the Royal Society, and in the supplementary volume on differential equations, edited by Isaac Todhunter. To the Cambridge Mathematical Journal and its successor, the Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal, Boole contributed 22 articles in all. In the third and fourth series of the Philosophical Magazine are found 16 papers. The Royal Society printed six memoirs in the Philosophical Transactions, and a few other memoirs are to be found in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and of the Royal Irish Academy, in the Bulletin de l'Académie de St-Pétersbourg for 1862 (under the name G. Boldt, vol. iv. pp. 198–215), and in Crelle's Journal. Also included is a paper on the mathematical basis of logic, published in The Mechanics' Magazine in 1848.

- Andrei Nikolaevich Kolmogorov, Adolf Pavlovich Yushkevich (editors), Mathematics of the 19th Century: function theory according to Chebyshev, ordinary differential equations, calculus of variations, theory of finite differences (1998), pp. 130–2; Google Books Archived 10 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Jeremy Gray, Karen Hunger Parshall, Episodes in the History of Modern Algebra (1800–1950) (2007), p. 66; Google Books Archived 16 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- George Boole, The Mathematical Analysis of Logic, Being an Essay towards a Calculus of Deductive Reasoning Archived 11 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine (London, England: Macmillan, Barclay, & Macmillan, 1847).

- George Boole, A treatise on differential equations (1859), Internet Archive.

- George Boole, A treatise on the calculus of finite differences (1860), Internet Archive.

- Boole, George (1857). "On the Comparison of Transcendent, with Certain Applications to the Theory of Definite Integrals". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 147: 745–803. doi:10.1098/rstl.1857.0037. JSTOR 108643.

- Cima, Joseph A.; Matheson, Alec; Ross, William T. (2005). "The Cauchy transform". Quad domains and their applications. Oper. Theory Adv. Appl. Vol. 156. Basel: Birkhäuser. pp. 79–111. MR 2129737.

- John Corcoran, Aristotle's Prior Analytics and Boole's Laws of Thought, History and Philosophy of Logic, vol. 24 (2003), pp. 261–288.

- Grattan-Guinness, I. "Boole, George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2868. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Witold Marciszewski (editor), Dictionary of Logic as Applied in the Study of Language (1981), pp. 194–5.

- Corcoran, John (2003). "Aristotle's Prior Analytics and Boole's Laws of Thought". History and Philosophy of Logic, 24: 261–288. Reviewed by Risto Vilkko. Bulletin of Symbolic Logic, 11(2005) 89–91. Also by Marcel Guillaume, Mathematical Reviews 2033867 (2004m:03006).

- George Boole. 1854/2003. The Laws of Thought, facsimile of 1854 edition, with an introduction by John Corcoran. Buffalo: Prometheus Books (2003). Reviewed by James van Evra in Philosophy in Review.24 (2004) 167–169.

- Andrei Nikolaevich Kolmogorov, Adolf Pavlovich Yushkevich, Mathematics of the 19th century: mathematical logic, algebra, number theory, probability theory (2001), pp. 15 (note 15)–16; Google Books Archived 17 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Burris, Stanley. "The Algebra of Logic Tradition". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Boole, George (1854). An Investigation of the Laws of Thought. London: Walton & Maberly. pp. 265–275. ISBN 9780790592428.

- "Dublin City Quick Search: Buildings of Ireland: National Inventory of Architectural Heritage". Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Barker, Tommy (13 June 2015). "Have a look inside the home of UCC maths professor George Boole". Irish Examiner. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- C., Bruno, Leonard (2003) [1999]. Math and mathematicians : the history of math discoveries around the world. Baker, Lawrence W. Detroit, Mich.: U X L. pp. 52. ISBN 0787638137. OCLC 41497065.

- Burris, Stanley (2 September 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019 – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "George Boole". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 30 January 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- "Death-His Life-- George Boole 200". Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- P. J. Brown, Pascal from Basic, Addison-Wesley, 1982. ISBN 0-201-13789-5, page 72

- "Boole Centre for Research in Informatics". Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- Ivor Grattan-Guinness, Gérard Bornet, George Boole: Selected manuscripts on logic and its philosophy (1997), p. xlvi; Google Books Archived 25 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Chapter XVI, p. 167, section 6 of A treatise on probability, volume 4: "The central error in his system of probability arises out of his giving two inconsistent definitions of 'independence' (2) He first wins the reader's acquiescence by giving a perfectly correct definition: "Two events are said to be independent when the probability of either of them is unaffected by our expectation of the occurrence or failure of the other." (3) But a moment later he interprets the term in quite a different sense; for, according to Boole's second definition, we must regard the events as independent unless we are told either that they must concur or that they cannot concur. That is to say, they are independent unless we know for certain that there is, in fact, an invariable connection between them. "The simple events, x, y, z, will be said to be conditioned when they are not free to occur in every possible combination; in other words, when some compound event depending upon them is precluded from occurring. ... Simple unconditioned events are by definition independent." (1) In fact as long as xz is possible, x and z are independent. This is plainly inconsistent with Boole's first definition, with which he makes no attempt to reconcile it. The consequences of his employing the term independence in a double sense are far-reaching. For he uses a method of reduction which is only valid when the arguments to which it is applied are independent in the first sense and assumes that it is valid if they are independent in the second sense. While his theorems are true if all propositions or events involved are independent in the first sense, they are not true, as he supposes them to be, if the events are independent only in the second sense."

- "ZETETIC GLEANINGS". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- "That dissertation has since been hailed as one of the most significant master's theses of the 20th century. To all intents and purposes, its use of binary code and Boolean algebra paved the way for the digital circuitry that is crucial to the operation of modern computers and telecommunications equipment."Emerson, Andrew (8 March 2001). "Claude Shannon". The Guardian. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "George Boole 200 – George Boole Bicentenary Celebrations". Archived from the original on 21 September 2014.

- "Cork University Press". Archived from the original on 8 November 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- 1902 Britannica article by Jevons; online text. Archived 16 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- James Gasser, A Boole Anthology: recent and classical studies in the logic of George Boole (2000), p. 5; Google Books Archived 10 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Gasser, p. 10; Google Books Archived 11 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Boole, George (1851). The Claims of Science, especially as founded in its relations to human nature; a lecture. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Boole, George (1855). The Social Aspect of Intellectual Culture: an address delivered in the Cork Athenæum, May 29th, 1855 : at the soirée of the Cuvierian Society. George Purcell & Co. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- International Association for Semiotic Studies; International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies; International Social Science Council (1995). "A tale of two amateurs". Semiotica, Volume 105. Mouton. p. 56.

MacHale's biography calls George Boole 'an agnostic deist'. Both Booles' classification of 'religious philosophies' as monistic, dualistic, and trinitarian left little doubt about their preference for 'the unity religion', whether Judaic or Unitarian.

- International Association for Semiotic Studies; International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies; International Social Science Council (1996). Semiotica, Volume 105. Mouton. p. 17.

MacHale does not repress this or other evidence of the Boole's nineteenth-century beliefs and practices in the paranormal and in religious mysticism. He even concedes that George Boole's many distinguished contributions to logic and mathematics may have been motivated by his distinctive religious beliefs as an "agnostic deist" and by an unusual personal sensitivity to the sufferings of other people.

- Boole, George. Studies in Logic and Probability. 2002. Courier Dover Publications. p. 201-202

- Boole, George. Studies in Logic and Probability. 2002. Courier Dover Publications. p. 451

- Some-Side of a Scientific Mind (2013). pp. 112–3. The University Magazine, 1878. London: Forgotten Books. (Original work published 1878)

- Concluding remarks of his treatise of "Clarke and Spinoza", as found in Boole, George (2007). An Investigation of the Laws of Thought. Cosimo, Inc. Chap . XIII. p. 217-218. (Original work published 1854)

- Boole, George (1851). The claims of science, especially as founded in its relations to human nature; a lecture, Volume 15. p. 24

- Jonardon Ganeri (2001), Indian Logic: a reader, Routledge, p. 7, ISBN 0-7007-1306-9; Google Books Archived 19 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Boole, Mary Everest Indian Thought and Western Science in the Nineteenth Century, Boole, Mary Everest Collected Works eds. E. M. Cobham and E. S. Dummer, London, Daniel 1931 pp.947–967

- Grattan-Guinness and Bornet, p. 16; Google Books Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kak, S. (2018) George Boole’s Laws of Thought and Indian logic. Current Science, vol. 114, 2570–2573

- "Family and Genealogy – His Life George Boole 200". Georgeboole.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Smothers In Orchard in The Los Angeles Times v. 27 February 1909.

- `My Right To Die´, Woman Kills Self in The Washington Times v. 28 May 1908 (PDF Archived 5 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine); Mrs. Mary Hinton A Suicide in The New York Times v. 29 May 1908 (PDF Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine).

- D. MacHale, The Life and Work of George Boole: A Prelude to the Digital Age, Cork University Press, 2014. cited in The Extraordinary Case of the Boole Family Archived 16 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine by Moira Chas

References

- Walker, A. (ed) (2019) George Boole's Lincoln, 1815–49. The Survey of Lincoln, Vol.16. ISBN 9780993126352

- University College Cork, George Boole 200 Bicentenary Celebration, GeorgeBoole.com.

- Ivor Grattan-Guinness, The Search for Mathematical Roots 1870–1940. Princeton University Press. 2000.

- Francis Hill (1974), Victorian Lincoln; Google Books Archived 17 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Des MacHale, George Boole: His Life and Work. Boole Press. 1985.

- Des MacHale, The Life and Work of George Boole: A Prelude to the Digital Age (new edition). Cork University Press Archived 8 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine. 2014

- Stephen Hawking, God Created the Integers. Running Press, Philadelphia. 2007.

External links

- Roger Parsons' article on Boole

- Works by George Boole at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about George Boole at Internet Archive

- The Calculus of Logic by George Boole; a transcription of an article which originally appeared in Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal, Vol. III (1848), pp. 183–98.

- George Boole's work as first Professor of Mathematics in University College, Cork, Ireland Archived 19 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- George Boole website

- Author profile in the database zbMATH

- The Genius of George Boole on YouTube