Mathematics

Mathematics (from Ancient Greek μάθημα; máthēma: 'knowledge, study, learning') is an area of knowledge that includes such topics as numbers (arithmetic and number theory),[2] formulas and related structures (algebra),[3] shapes and the spaces in which they are contained (geometry),[2] and quantities and their changes (calculus and analysis).[4][5][6]

| Mathematics | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Portal | ||

Most mathematical activity involves the discovery of properties of abstract objects and the use of pure reason to prove them. These objects consist of either abstractions from nature or—in modern mathematics—entities that are stipulated with certain properties, called axioms. A proof consists of a succession of applications of deductive rules to already established results. These results include previously proved theorems, axioms, and—in case of abstraction from nature—some basic properties that are considered as true starting points of the theory under consideration.[7]

Mathematics is used in science for modeling phenomena, which then allows predictions to be made from experimental laws. The independence of mathematical truth from any experimentation implies that the accuracy of such predictions depends only on the adequacy of the model. Inaccurate predictions, rather than being caused by incorrect mathematics, imply the need to change the mathematical model used. For example, the perihelion precession of Mercury could only be explained after the emergence of Einstein's general relativity, which replaced Newton's law of gravitation as a better mathematical model.

Mathematics is essential in the natural sciences, engineering, medicine, finance, computer science and the social sciences. The fundamental truths of mathematics are independent from any scientific experimentation, although mathematics is extensively used for modeling phenomena. Some areas of mathematics, such as statistics and game theory, are developed in close correlation with their applications and are often grouped under applied mathematics. Other mathematical areas are developed independently from any application (and are therefore called pure mathematics), but practical applications are often discovered later.[8][9] A fitting example is the problem of integer factorization, which goes back to Euclid, but which had no practical application before its use in the RSA cryptosystem (for the security of computer networks).

Historically, the concept of a proof and its associated mathematical rigour first appeared in Greek mathematics, most notably in Euclid's Elements.[10] Since its beginning, mathematics was essentially divided into geometry, and arithmetic (the manipulation of natural numbers and fractions), until the 16th and 17th centuries, when algebra[lower-alpha 1] and infinitesimal calculus were introduced as new areas of the subject. Since then, the interaction between mathematical innovations and scientific discoveries has led to a rapid increase in the development of mathematics. At the end of the 19th century, the foundational crisis of mathematics led to the systematization of the axiomatic method. This gave rise to a dramatic increase in the number of mathematics areas and their fields of applications. This can be seen, for example, in the contemporary Mathematics Subject Classification, which lists more than 60 first-level areas of mathematics.

Etymology

The word mathematics comes from Ancient Greek máthēma (μάθημα), meaning "that which is learnt,"[11] "what one gets to know," hence also "study" and "science". The word for "mathematics" came to have the narrower and more technical meaning "mathematical study" even in Classical times.[12] Its adjective is mathēmatikós (μαθηματικός), meaning "related to learning" or "studious," which likewise further came to mean "mathematical." In particular, mathēmatikḗ tékhnē (μαθηματικὴ τέχνη; Latin: ars mathematica) meant "the mathematical art."

Similarly, one of the two main schools of thought in Pythagoreanism was known as the mathēmatikoi (μαθηματικοί)—which at the time meant "learners" rather than "mathematicians" in the modern sense. The Pythagoreans were likely the first to constrain the use of the word to just the study of arithmetic and geometry. By the time of Aristotle this meaning was fully established.[13]

In Latin, and in English until around 1700, the term mathematics more commonly meant "astrology" (or sometimes "astronomy") rather than "mathematics"; the meaning gradually changed to its present one from about 1500 to 1800. This has resulted in several mistranslations. For example, Saint Augustine's warning that Christians should beware of mathematici, meaning astrologers, is sometimes mistranslated as a condemnation of mathematicians.[14]

The apparent plural form in English goes back to the Latin neuter plural mathematica (Cicero), based on the Greek plural ta mathēmatiká (τὰ μαθηματικά), used by Aristotle (384–322 BC), and meaning roughly "all things mathematical", although it is plausible that English borrowed only the adjective mathematic(al) and formed the noun mathematics anew, after the pattern of physics and metaphysics, which were inherited from Greek.[15] In English, the noun mathematics takes a singular verb. It is often shortened to maths or, in North America, math.[16]

Areas of mathematics

Before the Renaissance, mathematics was divided into two main areas: arithmetic — regarding the manipulation of numbers, and geometry — regarding the study of shapes.[17] Some types of pseudoscience, such as numerology and astrology, were not then clearly distinguished from mathematics.[18]

During the Renaissance, two more areas appeared. Mathematical notation led to algebra, which, roughly speaking, consists of the study and the manipulation of formulas. Calculus, consisting of the two subfields infinitesimal calculus and integral calculus, is the study of continuous functions, which model the typically nonlinear relationships between varying quantities (variables). This division into four main areas–arithmetic, geometry, algebra, calculus[19]–endured until the end of the 19th century. Areas such as celestial mechanics and solid mechanics were often then considered as part of mathematics, but now are considered as belonging to physics. Some subjects developed during this period predate mathematics and are divided into such areas as probability theory and combinatorics, which only later became regarded as autonomous areas.

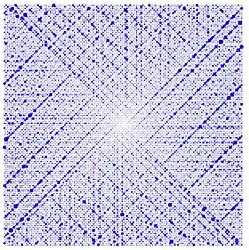

At the end of the 19th century, the foundational crisis in mathematics and the resulting systematization of the axiomatic method led to an explosion of new areas of mathematics.[20] The 2020 Mathematics Subject Classification contains no less than sixty-three first-level areas.[21] Some of these areas correspond to the older division, as is true regarding number theory (the modern name for higher arithmetic) and geometry. Several other first-level areas have "geometry" in their names or are otherwise commonly considered part of geometry. Algebra and calculus do not appear as first-level areas but are respectively split into several first-level areas. Other first-level areas emerged during the 20th century (for example category theory; homological algebra, and computer science) or had not previously been considered as mathematics, such as Mathematical logic and foundations (including model theory, computability theory, set theory, proof theory, and algebraic logic).

Number theory

Number theory began with the manipulation of numbers, that is, natural numbers and later expanded to integers and rational numbers Formerly, number theory was called arithmetic, but nowadays this term is mostly used for numerical calculations.

Many easily-stated number problems have solutions that require sophisticated methods from across mathematics. One prominent example is Fermat's last theorem. This conjecture was stated in 1637 by Pierre de Fermat, but it was proved only in 1994 by Andrew Wiles, who used tools including scheme theory from algebraic geometry, category theory and homological algebra. Another example is Goldbach's conjecture, which asserts that every even integer greater than 2 is the sum of two prime numbers. Stated in 1742 by Christian Goldbach, it remains unproven to this day despite considerable effort.

Number theory includes several subareas, including analytic number theory, algebraic number theory, geometry of numbers (method oriented), diophantine equations, and transcendence theory (problem oriented).

Geometry

Geometry is one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It started with empirical recipes concerning shapes, such as lines, angles and circles, which were developed mainly for the needs of surveying and architecture, but has since blossomed out into many other subfields.

A fundamental innovation was the introduction of the concept of proofs by ancient Greeks, with the requirement that every assertion must be proved. For example, it is not sufficient to verify by measurement that, say, two lengths are equal; their equality must be proven via reasoning from previously accepted results (theorems) and a few basic statements. The basic statements are not subject to proof because they are self-evident (postulates), or they are a part of the definition of the subject of study (axioms). This principle, which is foundational for all mathematics, was first elaborated for geometry, and was systematized by Euclid around 300 BC in his book Elements.[22][23]

The resulting Euclidean geometry is the study of shapes and their arrangements constructed from lines, planes and circles in the Euclidean plane (plane geometry) and the (three-dimensional) Euclidean space.[lower-alpha 2]

Euclidean geometry was developed without change of methods or scope until the 17th century, when René Descartes introduced what is now called Cartesian coordinates. This was a major change of paradigm, since instead of defining real numbers as lengths of line segments (see number line), it allowed the representation of points using their coordinates (which are numbers). This allows one to use algebra (and later, calculus) to solve geometrical problems. This split geometry into two new subfields: synthetic geometry, which uses purely geometrical methods, and analytic geometry, which uses coordinates systemically.[24]

Analytic geometry allows the study of curves that are not related to circles and lines. Such curves can be defined as graph of functions (whose study led to differential geometry). They can also be defined as implicit equations, often polynomial equations (which spawned algebraic geometry). Analytic geometry also makes it possible to consider spaces of higher than three dimensions.

In the 19th century, mathematicians discovered non-Euclidean geometries, which do not follow the parallel postulate. By questioning the truth of that postulate, this discovery joins Russel's paradox as revealing the foundational crisis of mathematics. This aspect of the crisis was solved by systematizing the axiomatic method, and adopting that the truth of the chosen axioms is not a mathematical problem. In turn, the axiomatic method allows for the study of various geometries obtained either by changing the axioms or by considering properties that are invariant under specific transformations of the space.

In the present day, the subareas of geometry include:

- Projective geometry, introduced in the 16th century by Girard Desargues, extends Euclidean geometry by adding points at infinity at which parallel lines intersect. This simplifies many aspects of classical geometry by unifying the treatments for intersecting and parallel lines.

- Affine geometry, the study of properties relative to parallelism and independent from the concept of length.

- Differential geometry, the study of curves, surfaces, and their generalizations, which are defined using differentiable functions

- Manifold theory, the study of shapes that are not necessarily embedded in a larger space

- Riemannian geometry, the study of distance properties in curved spaces

- Algebraic geometry, the study of curves, surfaces, and their generalizations, which are defined using polynomials

- Topology, the study of properties that are kept under continuous deformations

- Algebraic topology, the use in topology of algebraic methods, mainly homological algebra

- Discrete geometry, the study of finite configurations in geometry

- Convex geometry, the study of convex sets, which takes its importance from its applications in optimization

- Complex geometry, the geometry obtained by replacing real numbers with complex numbers

Triangle on a paraboloid

Triangle on a paraboloid

Algebra

Algebra is the art of manipulating equations and formulas. Diophantus (3rd century) and al-Khwarizmi (9th century) were the two main precursors of algebra. The first one solved some equations involving unknown natural numbers by deducing new relations until he obtained the solution. The second one introduced systematic methods for transforming equations (such as moving a term from a side of an equation into the other side). The term algebra is derived from the Arabic word al-jabr meaning "the reunion of broken parts"[25] that he used for naming one of these methods in the title of his main treatise.

Algebra became an area in its own right only with François Viète (1540–1603), who introduced the use of letters (variables) for representing unknown or unspecified numbers. This allows mathematicians to describe the operations that have to be done on the numbers represented using mathematical formulas.

Until the 19th century, algebra consisted mainly of the study of linear equations (presently linear algebra), and polynomial equations in a single unknown, which were called algebraic equations (a term that is still in use, although it may be ambiguous). During the 19th century, mathematicians began to use variables to represent things other than numbers (such as matrices, modular integers, and geometric transformations), on which generalizations of arithmetic operations are often valid. The concept of algebraic structure addresses this, consisting of a set whose elements are unspecified, of operations acting on the elements of the set, and rules that these operations must follow. Due to this change, the scope of algebra grew to include the study of algebraic structures. This object of algebra was called modern algebra or abstract algebra. (The latter term appears mainly in an educational context, in opposition to elementary algebra, which is concerned with the older way of manipulating formulas.)

Some types of algebraic structures have useful and often fundamental properties, in many areas of mathematics. Their study became autonomous parts of algebra, and include:

- group theory;

- field theory;

- vector spaces, whose study is essentially the same as linear algebra;

- ring theory;

- commutative algebra, which is the study of commutative rings, includes the study of polynomials, and is a foundational part of algebraic geometry;

- homological algebra

- Lie algebra and Lie group theory;

- Boolean algebra, which is widely used for the study of the logical structure of computers.

The study of types of algebraic structures as mathematical objects is the object of universal algebra and category theory. The latter applies to every mathematical structure (not only algebraic ones). At its origin, it was introduced, together with homological algebra for allowing the algebraic study of non-algebraic objects such as topological spaces; this particular area of application is called algebraic topology.

Calculus and analysis

Calculus, formerly called infinitesimal calculus, was introduced independently and simultaneously by 17th-century mathematicians Newton and Leibniz. It is fundamentally the study of the relationship of variables that depend on each other. Calculus was expanded in the 18th century by Euler with the introduction of the concept of a function and many other results. Presently, "calculus" refers mainly to the elementary part of this theory, and "analysis" is commonly used for advanced parts.

Analysis is further subdivided into real analysis, where variables represent real numbers, and complex analysis, where variables represent complex numbers. Analysis includes many subareas shared by other areas of mathematics which include:

- Multivariable calculus

- Functional analysis, where variables represent varying functions;

- Integration, measure theory and potential theory, all strongly related with Probability theory;

- Ordinary differential equations;

- Partial differential equations;

- Numerical analysis, mainly devoted to the computation on computers of solutions of ordinary and partial differential equations that arise in many applications.

Discrete mathematics

Discrete mathematics, broadly speaking, is the study of finite mathematical objects. Because the objects of study here are discrete, the methods of calculus and mathematical analysis do not directly apply.[lower-alpha 3] Algorithms – especially their implementation and computational complexity – play a major role in discrete mathematics.

Discrete mathematics includes:

- Combinatorics, the art of enumerating mathematical objects that satisfy some given constraints. Originally, these objects were elements or subsets of a given set; this has been extended to various objects, which establishes a strong link between combinatorics and other parts of discrete mathematics. For example, discrete geometry includes counting configurations of geometric shapes

- Graph theory and hypergraphs

- Coding theory, including error correcting codes and a part of cryptography

- Matroid theory

- Discrete geometry

- Discrete probability distributions

- Game theory (although continuous games are also studied, most common games, such as chess and poker are discrete)

- Discrete optimization, including combinatorial optimization, integer programming, constraint programming

The four color theorem and optimal sphere packing were two major problems of discrete mathematics solved in the second half of the 20th century. The P versus NP problem, which remains open to this day, is also important for discrete mathematics, since its solution would impact much of it.

Mathematical logic and set theory

The two subjects of mathematical logic and set theory have both belonged to mathematics since the end of the 19th century.[26][27] Before this period, sets were not considered to be mathematical objects, and logic, although used for mathematical proofs, belonged to philosophy, and was not specifically studied by mathematicians.

Before Cantor's study of infinite sets, mathematicians were reluctant to consider actually infinite collections, and considered infinity to be the result of endless enumeration. Cantor's work offended many mathematicians not only by considering actually infinite sets,[28] but by showing that this implies different sizes of infinity (see Cantor's diagonal argument) and the existence of mathematical objects that cannot be computed, or even explicitly described (for example, Hamel bases of the real numbers over the rational numbers). This led to the controversy over Cantor's set theory.

In the same period, various areas of mathematics concluded the former intuitive definitions of the basic mathematical objects were insufficient for ensuring mathematical rigour. Examples of such intuitive definitions are "a set is a collection of objects", "natural number is what is used for counting", "a point is a shape with a zero length in every direction", "a curve is a trace left by a moving point", etc.

This became the foundational crisis of mathematics.[29] It was eventually solved in mainstream mathematics by systematizing the axiomatic method inside a formalized set theory. Roughly speaking, each mathematical object is defined by the set of all similar objects and the properties that these objects must have. For example, in Peano arithmetic, the natural numbers are defined by "zero is a number", "each number has a unique successor", "each number but zero has a unique predecessor", and some rules of reasoning. The "nature" of the objects defined this way is a philosophical problem that mathematicians leave to philosophers, even if many mathematicians have opinions on this nature, and use their opinion—sometimes called "intuition"—to guide their study and proofs.

This approach allows considering "logics" (that is, sets of allowed deducing rules), theorems, proofs, etc. as mathematical objects, and to prove theorems about them. For example, Gödel's incompleteness theorems assert, roughly speaking that, in every theory that contains the natural numbers, there are theorems that are true (that is provable in a larger theory), but not provable inside the theory.

This approach to the foundations of mathematics was challenged during the first half of the 20th century by mathematicians led by Brouwer, who promoted intuitionistic logic, which explicitly lacks the law of excluded middle.

These problems and debates led to a wide expansion of mathematical logic, with subareas such as model theory (modeling some logical theories inside other theories), proof theory, type theory, computability theory and computational complexity theory. Although these aspects of mathematical logic were introduced before the rise of computers, their use in compiler design, program certification, proof assistants and other aspects of computer science, contributed in turn to the expansion of these logical theories.[30]

Statistics and other decision sciences

The field of statistics is a type of mathematical application that is employed for the collection and processing of data samples, using procedures based on mathematical methods especially probability theory. Statisticians generate data with random sampling or randomized experiments.[32] The design of a statistical sample or experiment determines the analytical methods that will be used. Analysis of data from observational studies is done using statistical models and the theory of inference, using model selection and estimation. The models and consequential predictions should then be tested against new data.[lower-alpha 4]

Statistical theory studies decision problems such as minimizing the risk (expected loss) of a statistical action, such as using a procedure in, for example, parameter estimation, hypothesis testing, and selecting the best. In these traditional areas of mathematical statistics, a statistical-decision problem is formulated by minimizing an objective function, like expected loss or cost, under specific constraints: For example, designing a survey often involves minimizing the cost of estimating a population mean with a given level of confidence.[33] Because of its use of optimization, the mathematical theory of statistics overlaps with other decision sciences, such as operations research, control theory, and mathematical economics.[34]

Computational mathematics

Computational mathematics is the study of mathematical problems that are typically too large for human, numerical capacity. Numerical analysis studies methods for problems in analysis using functional analysis and approximation theory; numerical analysis broadly includes the study of approximation and discretization with special focus on rounding errors. Numerical analysis and, more broadly, scientific computing also study non-analytic topics of mathematical science, especially algorithmic-matrix-and-graph theory. Other areas of computational mathematics include computer algebra and symbolic computation.

History

Ancient

The history of mathematics is an ever-growing series of abstractions. Evolutionarily speaking, the first abstraction to ever be discovered, one shared by many animals,[35] was probably that of numbers: the realization that, for example, a collection of two apples and a collection of two oranges (say) have something in common, namely that there are two of them. As evidenced by tallies found on bone, in addition to recognizing how to count physical objects, prehistoric peoples may have also known how to count abstract quantities, like time—days, seasons, or years.[36][37]

Evidence for more complex mathematics does not appear until around 3000 BC, when the Babylonians and Egyptians began using arithmetic, algebra, and geometry for taxation and other financial calculations, for building and construction, and for astronomy.[38] The oldest mathematical texts from Mesopotamia and Egypt are from 2000 to 1800 BC. Many early texts mention Pythagorean triples and so, by inference, the Pythagorean theorem seems to be the most ancient and widespread mathematical concept after basic arithmetic and geometry. It is in Babylonian mathematics that elementary arithmetic (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) first appear in the archaeological record. The Babylonians also possessed a place-value system and used a sexagesimal numeral system which is still in use today for measuring angles and time.[39]

In the 6th century BC, Greek mathematics began to emerge as a distinct discipline and some Ancient Greeks such as the Pythagoreans appeared to have considered it a subject in its own right.[40] Around 300 BC, Euclid organized mathematical knowledge by way of postulates and first principles, which evolved into the axiomatic method that is used in mathematics today, consisting of definition, axiom, theorem, and proof.[41] His book, Elements, is widely considered the most successful and influential textbook of all time.[42] The greatest mathematician of antiquity is often held to be Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC) of Syracuse.[43] He developed formulas for calculating the surface area and volume of solids of revolution and used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area under the arc of a parabola with the summation of an infinite series, in a manner not too dissimilar from modern calculus.[44] Other notable achievements of Greek mathematics are conic sections (Apollonius of Perga, 3rd century BC),[45] trigonometry (Hipparchus of Nicaea, 2nd century BC),[46] and the beginnings of algebra (Diophantus, 3rd century AD).[47]

The Hindu–Arabic numeral system and the rules for the use of its operations, in use throughout the world today, evolved over the course of the first millennium AD in India and were transmitted to the Western world via Islamic mathematics. Other notable developments of Indian mathematics include the modern definition and approximation of sine and cosine, and an early form of infinite series.

Medieval and later

During the Golden Age of Islam, especially during the 9th and 10th centuries, mathematics saw many important innovations building on Greek mathematics. The most notable achievement of Islamic mathematics was the development of algebra. Other achievements of the Islamic period include advances in spherical trigonometry and the addition of the decimal point to the Arabic numeral system.[48] Many notable mathematicians from this period were Persian, such as Al-Khwarismi, Omar Khayyam and Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī.

During the early modern period, mathematics began to develop at an accelerating pace in Western Europe. The development of calculus by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz in the 17th century revolutionized mathematics. Leonhard Euler was the most notable mathematician of the 18th century, contributing numerous theorems and discoveries. Perhaps the foremost mathematician of the 19th century was the German mathematician Carl Gauss, who made numerous contributions to fields such as algebra, analysis, differential geometry, matrix theory, number theory, and statistics. In the early 20th century, Kurt Gödel transformed mathematics by publishing his incompleteness theorems, which show in part that any consistent axiomatic system—if powerful enough to describe arithmetic—will contain true propositions that cannot be proved.

Mathematics has since been greatly extended, and there has been a fruitful interaction between mathematics and science, to the benefit of both. Mathematical discoveries continue to be made to this very day. According to Mikhail B. Sevryuk, in the January 2006 issue of the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, "The number of papers and books included in the Mathematical Reviews database since 1940 (the first year of operation of MR) is now more than 1.9 million, and more than 75 thousand items are added to the database each year. The overwhelming majority of works in this ocean contain new mathematical theorems and their proofs."[49]

Symbolic notation and terminology

Mathematical notation is widely used in mathematics, science, and engineering for representing complex concepts and properties in a concise, unambiguous and accurate way.

Mathematical notation consists of using symbols for representing operations, unspecified numbers, relations and any other mathematical objects, and assembling them into expressions and formulas.

More precisely, numbers and other mathematical objects are represented by symbols called variables, which are generally Latin or Greek letters, and include often subscripts. Operation and relations are generally represented by specific glyphs, such as + (plus), × (multiplication), (integral), = (equal), < (less than). All these symbols are generally grouped according to specific rules to form expressions and formulas. Normally, expressions and formulas do not appear alone, but are included in sentences of the current language, where expressions play the role of noun phrases and formulas play the role of clauses.

Many technical terms used in mathematics are often neologisms, such as polynomial and homeomorphism. Many other technical terms are words of the common language that are used in an accurate meaning that may differs slightly from their common meaning. For example, in mathematics, "or" means "one, the other or both", while, in common language, it is either amiguous or means "one or the other but not both" (in mathematics, the latter is called "exclusive or").

Also, many mathematical terms are common words that are used with a completely different meaning. This may lead to sentences that are correct and true mathematical assertions, but appear to be nonsense to people who do not have the required background. For example, "every free module is flat" and "a field is always a ring".

Relationship with science

Mathematics is used in science for modeling phenomena, which then allows predictions to be made from experimental laws. The independence of mathematical truth from any experimentation implies that the accuracy of such predictions depends only on the adequacy of the model. Inaccurate predictions, rather than being caused by incorrect mathematics, imply the need to change the mathematical model used. For example, the perihelion precession of Mercury could only be explained after the emergence of Einstein's general relativity, which replaced Newton's law of gravitation as a better mathematical model.

There is still a philosophical debate whether mathematics is a science. However, in practice, mathematicians are typically grouped with scientists, and mathematics shares much in common with the physical sciences. Like them, it is falsifiable, which means in mathematics that, if a result or a theory is wrong, this can be proved by providing a counterexample. Similarly as in science, theories and results (theorems) are often obtained from experimentation.[50] In mathematics, the experimentation may consist of computation on selected examples or of the study of figures or other representations of mathematical objects (often mind representations without physical support). For example, when asked how he came about his theorems, Gauss (one of the greatest mathematicians of the 19th century) once replied "durch planmässiges Tattonieren" (through systematic experimentation).[51] However, some authors emphasize that mathematics differs from the modern notion of science by not relying on empirical evidence.[52][53][54][55]

What precedes is only one aspect of the relationship between mathematics and other sciences. Other aspects are considered in the next subsections.

Pure and applied mathematics

Until the end of the 19th century, the development of mathematics was mainly motivated by the needs of technology and science, and there was no clear distinction between pure and applied mathematics. For example, the natural numbers and arithmetic were introduced for the need of counting, and geometry was motivated by surveying, architecture and astronomy. Later, Isaac Newton introduced infinitesimal calculus for explaining the movement of the planets with his law of gravitation. Moreover, most mathematicians were also scientists, and many scientists were also mathematicians. However, a notable exception occurred in Ancient Greece; see Pure mathematics § Ancient Greece.

In the second half ot the 19th century, new mathematical theories were introduced which were not related with the physical world (at least at that time), in particular, non-Euclidean geometries and Cantor's theory of transfinite numbers. This was one of the starting points of the foundational crisis of mathematics, which was eventually solved by the systematization of the axiomatic method for defining mathematical structures.

So, many mathematicians focused their research on internal problems, that is, pure mathematics, and this led to split mathematics into pure mathematics and applied mathematics, the latter being often considered as having a lower value.

During the second half of the 20th century, it appeared that many theories issued from applications are also interesting from the point of view of pure mathematics, and that many results of pure mathematics have applications outside mathematics (see next section); in turn, the study of these applications may give new insights on the "pure theory". An example of the first case is the theory of distributions, introduced by Laurent Schwartz for validating computations done in quantum mechanics, which became immediately an important tool of (pure) mathematical analysis. An example of the second case is the decidability of the first-order theory of the real numbers, a problem of pure mathematics that was proved true by Alfred Tarski, with an algorithm that is definitely impossible to implement, because of a computational complexity that is much too high. For getting an algorithm that can be implemented and can solve systems of polynomial equations and inequalities, George Collins introduced the cylindrical algebraic decomposition that became a fundamental tool in real algebraic geometry.

So, the distinction between pure and applied mathematics is presently more a question of personal research aim of mathematicians than a division of mathematics into broad areas. The Mathematics Subject Classification does not mention "pure mathematics" nor "applied mathematics". However, these terms are still used in names of some university departments, such as at the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge.

Unreasonable effectiveness

The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics[9] is a phenomenon that was named and first made explicit by physicist Eugene Wigner. It is the fact that many mathematical theories, even the "purest" have applications outside their initial object. These applications may be completely outside their initial area of mathematics, and may concern physical phenomena that were completely unknown when the mathematical theory was introduced.

A famous example is the prime factorization of natural numbers that was discovered more than 2,000 years before its common use for secure internet communications through the RSA cryptosystem.

Another historical example is the theory of ellipses. They were studied by the ancient Greek mathematicians as conic sections (that is, intersections of cones with planes). It is almost 2,000 years later that Johannes Kepler discovered that the trajectories of the planets are ellipses.

In the 19th century, the internal development of geometry (pure mathematics) lead to define and study non-Euclidean geometries, spaces of dimension higher than three and manifolds. At this time, these concepts seemed totally disconnected from the physical reality, but at the beginning of the 20th century, Albert Einstein developed the theory of relativity that uses fundamentally these concepts. In particular, spacetime of the special relativity is a non-Euclidean space of dimension four, and spacetime of the general relativity is a (curved) manifold of dimension four.

Similar examples of unexpected applications of mathematical theories can be found in many areas of mathematics.

Another striking aspect of the interaction between mathematics and physics is when mathematics drives research in physics. This is illustrated by the discoveries of the positron and the baryon In both cases, the equations of the theories had unexplained solutions, which led to conjecture the existence of a unknown particle, and to search these particles. In both cases, these particles were discovered a few years later by specific experiments.[56]

Philosophy

Reality

The connection between mathematics and material reality has led to philosophical debates since at least the time of Pythagoras. The ancient philosopher Plato argued that abstractions that reflect material reality have themselves a reality that exists outside space and time. As a result, the philosophical view that mathematical objects somehow exist on their own in abstraction is often referred to as Platonism. Independently of their possible philosophical opinions, modern mathematicians may be generally considered as Platonists, since they think of and talk of their objects of study as real objects.[57]

Armand Borel summarized this view of mathematics reality as follows, and provided quotations of G. H. Hardy, Charles Hermite, Henri Poincaré and Albert Einstein that support his views.[56]

Something becomes objective (as opposed to "subjective") as soon as we are convinced that it exists in the minds of others in the same form as it does in ours and that we can think about it and discuss it together[58]. Because the language of mathematics is so precise, it is ideally suited to defining concepts for which such a consensus exists. In my opinion, that is sufficient to provide us with a feeling of an objective existence, of a reality of mathematics ...

Nevertheless, Platonism and the concurrent views on abstraction do not explain the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics.

Proposed definitions

There is no general consensus about a definition of mathematics or its epistemological status—that is, its place among other human activities.[59][60]

A great many professional mathematicians take no interest in a definition of mathematics, or consider it undefinable.[59] There is not even consensus on whether mathematics is an art or a science.[60] Some just say, "mathematics is what mathematicians do".[59] This makes sense, as there is a strong consensus among them about what is mathematics and what is not.

Most proposed definitions try to define mathematics by its object of study.

Aristotle defined mathematics as "the science of quantity" and this definition prevailed until the 18th century. However, Aristotle also noted a focus on quantity alone may not distinguish mathematics from sciences like physics; in his view, abstraction and studying quantity as a property "separable in thought" from real instances set mathematics apart.[61]

In the 19th century, when mathematicians began to address topics—such as infinite sets—which have no clear-cut relation to physical reality, a variety of new definitions were given.[62] With the large number of new areas of mathematics that appeared since the beginning of the 20th century and continue to appear, defining mathematics by this object of study becomes an impossible task.

Another approach for defining mathematics is to use its methods. So, an area of study can be qualified as mathematics as soon as one can prove theorems —assertions whose validity relies on a proof, that is, a purely-logical deduction.

Logic and rigor

Mathematicians strive to develop their results with systematic reasoning in order to avoid mistaken "theorems". These false proofs often arise from fallible intuitions and have been common in mathematics' history. To allow deductive reasoning, some basic assumptions need to be admitted explicitly as axioms. Traditionally, these axioms were selected on the grounds of common-sense, but modern axioms typically express formal guarantees for primitive notions, such as simple objects and relations.

The validity of a mathematical proof is fundamentally a matter of rigour, and misunderstanding rigor is a notable cause for some common misconceptions about mathematics. Mathematical language may give more precision than in everyday speech to ordinary words like or and only. Other words such as open and field are given new meanings for specific mathematical concepts. Sometimes, mathematicians even coin entirely new words (e.g. homeomorphism). This technical vocabulary is both precise and compact, making it possible to mentally process complex ideas. Mathematicians refer to this precision of language and logic as "rigor".

The rigor expected in mathematics has varied over time: the ancient Greeks expected detailed arguments, but in Isaac Newton's time, the methods employed were less rigorous (not because of a different conception of mathematics, but because of the lack of the mathematical methods that are required for reaching rigor). Problems inherent in Newton's approach were solved only in the second half of the 19th century, with the formal definitions of real numbers, limits and integrals. Later in the early 20th century, Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead would publish their Principia Mathematica, an attempt to show that all mathematical concepts and statements could be defined, then proven entirely through symbolic logic. This was part of a wider philosophical program known as logicism, which sees mathematics as primarily an extension of logic.

Despite mathematics' concision, many proofs require hundreds of pages to express. The emergence of computer-assisted proofs has allowed proof lengths to further expand. Assisted proofs may be erroneous if the proving software has flaws.[lower-alpha 6][63] On the other hand, proof assistants allow for the verification of details that cannot be given in a hand-written proof, and provide certainty of the correctness of long proofs such as that of the 255-page Feit–Thompson theorem.[lower-alpha 7]

Psychology (aesthetic, creativity and intuition)

The validity of a mathematical theorem relies only on the rigor of its proof, which could theoretically be done automatically by a computer program. This does not mean that there is no place for creativity in a mathematical work. On the contrary, many important mathematical results (theorems) are solutions of problems that other mathematicians failed to solve, and the invention of a way for solving them may be a fundamental way of the solving process. An extreme example is Apery's theorem: Roger Apery provided only the ideas for a proof, and the formal proof was given only several months later by three other mathematicians.

Creativity and rigor are not the only psychological aspects of the activity of mathematicians.

Many mathematicians see their activity as a game, more specifically as solving puzzles. This aspect of mathematical activity is emphasized in recreational mathematics.

Many mathematicians give also an aesthetic value to mathematics. Like beauty, it is hard to define, it is commonly related to elegance, which involves qualities like simplicity, symmetry, completeness, and generality. G. H. Hardy in A Mathematician's Apology expressed the belief that the aesthetic considerations are, in themselves, sufficient to justify the study of pure mathematics. He also identified other criteria such as significance, unexpectedness, and inevitability, which contribute to mathematical aesthetic.[64]

Paul Erdős expressed this sentiment more ironically by speaking of "The Book", a supposed divine collection of the most beautiful proofs. The 1998 book Proofs from THE BOOK, inspired by Erdős, is a collection of particularly succinct and revelatory mathematical arguments. Some examples of particularly elegant results included are Euclid's proof that there are infinitely many prime numbers and the fast Fourier transform for harmonic analysis.

Some feel that to consider mathematics a science is to downplay its artistry and history in the seven traditional liberal arts.[65] One way this difference of viewpoint plays out is in the philosophical debate as to whether mathematical results are created (as in art) or discovered (as in science).[56] The popularity of recreational mathematics is another sign of the pleasure many find in solving mathematical questions.

In the 20th century, the mathematician L. E. J. Brouwer even initiated a philosophical perspective known as intuitionism, which primarily identifies mathematics with certain creative processes in the mind.[66] Intuitionism is in turn one flavor of a stance known as constructivism, which only considers a mathematical object valid if it can be directly constructed, not merely guaranteed by logic indirectly. This leads committed constructivists to reject certain results, particularly arguments like existential proofs based on the law of excluded middle.[67]

In the end, neither constructivism nor intuitionism displaced classical mathematics or achieved mainstream acceptance. However, these programs have motivated specific developments, such as intuitionistic logic and other foundational insights, which are appreciated in their own right.[67]

Education

Mathematics has a remarkable ability to cross cultural boundaries and time periods. As a human activity, the practice of mathematics has a social side, which includes education, careers, recognition, popularization, and so on. In education, mathematics is a core part of the curriculum. While the content of courses varies, many countries in the world teach mathematics to students for significant amounts of time.[68]

Awards and prize problems

The most prestigious award in mathematics is the Fields Medal,[69][70] established in 1936 and awarded every four years (except around World War II) to up to four individuals.[71][72] It is considered the mathematical equivalent of the Nobel Prize.[72]

Other prestigious mathematics awards include:

- The Abel Prize, instituted in 2002[73] and first awarded in 2003[74]

- The Chern Medal for lifetime achievement, introduced in 2009[75] and first awarded in 2010[76]

- The Wolf Prize in Mathematics, also for lifetime achievement,[77] instituted in 1978[78]

A famous list of 23 open problems, called "Hilbert's problems", was compiled in 1900 by German mathematician David Hilbert.[79] This list has achieved great celebrity among mathematicians[80], and, as of 2022, at least thirteen of the problems (depending how some are interpreted) have been solved.[81]

A new list of seven important problems, titled the "Millennium Prize Problems", was published in 2000. Only one of them, the Riemann hypothesis, duplicates one of Hilbert's problems. A solution to any of these problems carries a 1 million dollar reward.[82] To date, only one of these problems, the Poincaré conjecture, has been solved.[83]

See also

- Outline of mathematics

- Lists of mathematics topics

- List of mathematical jargon

- Philosophy of mathematics

- Relationship between mathematics and physics

- Mathematical sciences

- Mathematics and art

- Mathematics education

- Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

- Lists of mathematicians

Notes

- Here, algebra is taken in its modern sense, which is, roughly speaking, the art of manipulating formulas.

- This includes conic sections, which are intersections of circular cylinders and planes.

- However, some advanced methods of analysis are sometimes used; for example, methods of complex analysis applied to generating series.

- Like other mathematical sciences such as physics and computer science, statistics is an autonomous discipline rather than a branch of applied mathematics. Like research physicists and computer scientists, research statisticians are mathematical scientists. Many statisticians have a degree in mathematics, and some statisticians are also mathematicians.

- No likeness or description of Euclid's physical appearance made during his lifetime survived antiquity. Therefore, Euclid's depiction in works of art depends on the artist's imagination.

- For considering as reliable a large computation occurring in a proof, one generally requires two computations using independent software

- The book containing the complete proof has more than 1,000 pages.

References

- Wells, David (1990). "Are these the most beautiful?". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 12 (3): 37–41. doi:10.1007/BF03024015. S2CID 121503263.

- "mathematics, n.". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2012. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

The science of space, number, quantity, and arrangement, whose methods involve logical reasoning and usually the use of symbolic notation, and which includes geometry, arithmetic, algebra, and analysis.

- Kneebone, G.T. (1963). Mathematical Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics: An Introductory Survey. Dover. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-486-41712-7. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

Mathematics ... is simply the study of abstract structures, or formal patterns of connectedness.

- LaTorre, Donald R.; Kenelly, John W.; Biggers, Sherry S.; Carpenter, Laurel R.; Reed, Iris B.; Harris, Cynthia R. (2011). Calculus Concepts: An Informal Approach to the Mathematics of Change. Cengage Learning. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4390-4957-0. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

Calculus is the study of change—how things change, and how quickly they change.

- Ramana, B. V. (2007). Applied Mathematics. Tata McGraw–Hill Education. p. 2.10. ISBN 978-0-07-066753-2. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

The mathematical study of change, motion, growth or decay is calculus.

- Ziegler, Günter M. (2011). "What Is Mathematics?". An Invitation to Mathematics: From Competitions to Research. Springer. p. vii. ISBN 978-3-642-19532-7. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Hipólito, Inês (August 2015). Kanzia, Mitterer, and Neges (ed.). "Abstract Cognition and the Nature of Mathematical Proof". Realism, Relativism, Constructivism. Austria: de Gruyter. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Peterson 2001, p. 12.

- Wigner, Eugene (1960). "The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences". Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics. 13 (1): 1–14. Bibcode:1960CPAM...13....1W. doi:10.1002/cpa.3160130102. Archived from the original on February 28, 2011.

- Wise, David. "Eudoxus' Influence on Euclid's Elements with a close look at The Method of Exhaustion". jwilson.coe.uga.edu. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- "mathematic (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013.

- Both meanings can be found in Plato, the narrower in Republic. 510c. Archived February 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, but Plato did not use a math- word; Aristotle did, commenting on it. μαθηματική. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project. OED Online. "Mathematics".

- Perisho, Margaret W. (Spring 1965). "The Etymology of Mathematical Terms". Pi Mu Epsilon Journal. 4 (2): 62–66. JSTOR 24338341.

- Boas, Ralph (1995) [1991]. "What Augustine Didn't Say About Mathematicians". Lion Hunting and Other Mathematical Pursuits: A Collection of Mathematics, Verse, and Stories by the Late Ralph P. Boas, Jr. Cambridge University Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-88385-323-8. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, Oxford English Dictionary, sub "mathematics", "mathematic", "mathematics".

- "maths, n." and "math, n.3" Archived April 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Oxford English Dictionary, on-line version (2012).

- Bell, E. T. (2012). The Development of Mathematics. Dover Books on Mathematics (reprint, revised ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 3. ISBN 9780486152288.

- Tiwari, Sarju (1992). Mathematics in History, Culture, Philosophy, and Science. Mittal Publications. p. 27. ISBN 9788170994046.

- Restivo, S. (December 2013). Mathematics in Society and History. Springer Netherlands. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9789401129442.

- Warner, Evan. "Splash Talk: The Foundational Crisis of Mathematics" (PDF). Columbia University. pp. 1–17. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- Dunne, Edward; Hulek, Klaus (March 2020). "Mathematics Subject Classification 2020" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 67 (3). Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- Hilbert, David (1962). The Foundations of Geometry. Open Court Publishing Company. p. 1.

- Hartshorne, Robin (November 11, 2013). Geometry: Euclid and Beyond. Springer New York. pp. 9–13. ISBN 9780387226767.

- Boyer, Carl B. (June 28, 2012). History of Analytic Geometry. Dover Publications. pp. 74–102. ISBN 9780486154510.

- "Where algebra got its x from, and Xmas its X". South China Morning Post. December 21, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- Ewald, William (November 17, 2018). "The Emergence of First-Order Logic". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- Ferreirós, José (June 18, 2020). "The Early Development of Set Theory". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- Wolchover, Natalie (December 3, 2013). "Dispute over Infinity Divides Mathematicians". Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- Hodgkin, Luke Howard (2005). A History of Mathematics: From Mesopotamia to Modernity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-152383-0.

- Halpern, Joseph; Harper, Robert; Immerman, Neil; Kolaitis, Phokion; Vardi, Moshe; Vianu, Victor (2001). "On the Unusual Effectiveness of Logic in Computer Science" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Rouaud, Mathieu (2013). Probability, Statistics and Estimation (PDF). p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Rao, C.R. (1997). Statistics and Truth: Putting Chance to Work. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-3111-8.

- Rao, C.R. (1981). "Foreword". In Arthanari, T.S.; Dodge, Yadolah (eds.). Mathematical programming in statistics. Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics. New York: Wiley. pp. vii–viii. ISBN 978-0-471-08073-2. MR 0607328.

- Whittle 1994, pp. 10–11, 14–18.

- Dehaene, Stanislas; Dehaene-Lambertz, Ghislaine; Cohen, Laurent (August 1998). "Abstract representations of numbers in the animal and human brain". Trends in Neurosciences. 21 (8): 355–61. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01263-6. PMID 9720604. S2CID 17414557.

- See, for example, Raymond L. Wilder. Evolution of Mathematical Concepts; an Elementary Study. passim.

- Zaslavsky, Claudia (1999). Africa Counts : Number and Pattern in African Culture. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61374-115-3. OCLC 843204342. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Kline 1990, Chapter 1.

- Boyer 1991, "Mesopotamia" pp. 24–27.

- Heath, Thomas Little (1981) [1921]. A History of Greek Mathematics: From Thales to Euclid. New York: Dover Publications. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-486-24073-2.

- Mueller, I. (1969). "Euclid's Elements and the Axiomatic Method". The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 20 (4): 289–309. doi:10.1093/bjps/20.4.289. ISSN 0007-0882. JSTOR 686258.

- Boyer 1991, "Euclid of Alexandria" p. 119.

- Boyer 1991, "Archimedes of Syracuse" p. 120.

- Boyer 1991, "Archimedes of Syracuse" p. 130.

- Boyer 1991, "Apollonius of Perga" p. 145.

- Boyer 1991, "Greek Trigonometry and Mensuration" p. 162.

- Boyer 1991, "Revival and Decline of Greek Mathematics" p. 180.

- Saliba, George. (1994). A history of Arabic astronomy : planetary theories during the golden age of Islam. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-7962-0. OCLC 28723059. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Sevryuk 2006, pp. 101–09.

- "The science checklist applied: Mathematics". undsci.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- Mackay, A. L. (1991). Dictionary of Scientific Quotations. London. p. 100.

- Bishop, Alan (1991). "Environmental activities and mathematical culture". Mathematical Enculturation: A Cultural Perspective on Mathematics Education. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 20–59. ISBN 978-0-7923-1270-3. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- Shasha, Dennis Elliot; Lazere, Cathy A. (1998). Out of Their Minds: The Lives and Discoveries of 15 Great Computer Scientists. Springer. p. 228.

- Nickles, Thomas (2013). "The Problem of Demarcation". Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 104.

- Pigliucci, Massimo (2014). "Are There 'Other' Ways of Knowing?". Philosophy Now. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Borel, Armand (1983). "Mathematics: Art and Science". The Mathematical Intelligencer. Springer. 5 (4): 9–17. doi:10.4171/news/103/8. ISSN 1027-488X.

- Balaguer, Mark (2016). "Platonism in Metaphysics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- See L. White (1947). "The locus of mathematical reality: An anthropological footnote". Philosophy of Science. 14. 189303; also in J.R. Newman (1956). The World of Mathematics. Vol. 4. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 2348–2364.

- Mura, Roberta (December 1993). "Images of Mathematics Held by University Teachers of Mathematical Sciences". Educational Studies in Mathematics. 25 (4): 375–85. doi:10.1007/BF01273907. JSTOR 3482762. S2CID 122351146.

- Tobies, Renate & Helmut Neunzert (2012). Iris Runge: A Life at the Crossroads of Mathematics, Science, and Industry. Springer. p. 9. ISBN 978-3-0348-0229-1. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

[I]t is first necessary to ask what is meant by mathematics in general. Illustrious scholars have debated this matter until they were blue in the face, and yet no consensus has been reached about whether mathematics is a natural science, a branch of the humanities, or an art form.

- Franklin, James (July 8, 2009). Philosophy of Mathematics. pp. 104–106. ISBN 978-0-08-093058-9. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- Cajori, Florian (1893). A History of Mathematics. American Mathematical Society (1991 reprint). pp. 285–86. ISBN 978-0-8218-2102-2.

- Peterson, Ivars (1988). The Mathematical Tourist. Freeman. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7167-1953-3.

A few complain that the computer program can't be verified properly

, (in reference to the Haken–Apple proof of the Four Color Theorem). - Hardy, G. H. (1940). A Mathematician's Apology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42706-7.

- See, for example Bertrand Russell's statement "Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty ..." in his History of Western Philosophy.

- Snapper, Ernst (September 1979). "The Three Crises in Mathematics: Logicism, Intuitionism, and Formalism". Mathematics Magazine. 52 (4): 207–16. doi:10.2307/2689412. JSTOR 2689412.

- Iemhoff, Rosalie (2020). "Intuitionism in the Philosophy of Mathematics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- Mullins, Ina V.S.; Martin, Micheal O.; Foy, Pierre; Kelly, Dana L.; Fishbein, Bethany (2020). TIMSS 2019 International Results in Mathematics and Science. TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education and Human Development, Boston College and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. pp. 448–451. ISBN 978-1-889938-54-7.

- Monastyrsky 2001, p. 1: "The Fields Medal is now indisputably the best known and most influential award in mathematics."

- Riehm 2002, pp. 778–82.

- "Fields Medal | International Mathematical Union (IMU)". www.mathunion.org. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- "Fields Medal". Maths History. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- "About the Abel Prize". The Abel Prize. Archived from the original on April 14, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- "Abel Prize | mathematics award". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- "CHERN MEDAL AWARD" (PDF). www.mathunion.org. June 1, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 17, 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- "Chern Medal Award". International Mathematical Union (IMU). Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- Chern, S. S.; Hirzebruch, F. (September 2000). Wolf Prize in Mathematics. doi:10.1142/4149. ISBN 978-981-02-3945-9. Archived from the original on February 21, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- "The Wolf Prize". Wolf Foundation. Archived from the original on January 12, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- "Hilbert's Problems: 23 and Math". Simons Foundation. May 6, 2020. Archived from the original on January 23, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- Newton, Tommy (2007). "A New Approach to Hilbert's Third Problem" (PDF). Western Kentucky University. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- "Hilbert's Problems: 23 and Math". Simons Foundation. May 6, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- "The Millennium Prize Problems". Clay Mathematics Institute. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- "Millennium Problems". Clay Mathematics Institute. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

Bibliography

- Boyer, Carl Benjamin (1991). A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-54397-8.

- Eves, Howard (1990). An Introduction to the History of Mathematics (6th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-0-03-029558-4.

- Kline, Morris (1990). Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times (Paperback ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506135-2.

- Monastyrsky, Michael (2001). "Some Trends in Modern Mathematics and the Fields Medal" (PDF). CMS – NOTES – de la SMC. Canadian Mathematical Society. 33 (2–3). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- Oakley, Barbara (2014). A Mind For Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even If You Flunked Algebra). New York: Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-399-16524-5.

A Mind for Numbers.

- Peirce, Benjamin (1881). Peirce, Charles Sanders (ed.). "Linear associative algebra". American Journal of Mathematics (Corrected, expanded, and annotated revision with an 1875 paper by B. Peirce and annotations by his son, C.S. Peirce, of the 1872 lithograph ed.). 4 (1–4): 97–229. doi:10.2307/2369153. hdl:2027/hvd.32044030622997. JSTOR 2369153. Corrected, expanded, and annotated revision with an 1875 paper by B. Peirce and annotations by his son, C. S. Peirce, of the 1872 lithograph ed. Google Eprint and as an extract, D. Van Nostrand, 1882, Google Eprint. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2020..

- Peterson, Ivars (2001). Mathematical Tourist, New and Updated Snapshots of Modern Mathematics. Owl Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-7159-7.

- Popper, Karl R. (1995). "On knowledge". In Search of a Better World: Lectures and Essays from Thirty Years. New York: Routledge. Bibcode:1992sbwl.book.....P. ISBN 978-0-415-13548-1.

- Riehm, Carl (August 2002). "The Early History of the Fields Medal" (PDF). Notices of the AMS. 49 (7): 778–82. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2006. Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- Sevryuk, Mikhail B. (January 2006). "Book Reviews" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 43 (1): 101–09. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-05-01069-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2006. Retrieved June 24, 2006.

- Waltershausen, Wolfgang Sartorius von (1965) [first published 1856]. Gauss zum Gedächtniss. Sändig Reprint Verlag H. R. Wohlwend. ISBN 978-3-253-01702-5.

- Whittle, Peter (1994). "Almost home". In Kelly, F.P. (ed.). Probability, statistics and optimisation: A Tribute to Peter Whittle (previously "A realised path: The Cambridge Statistical Laboratory up to 1993 (revised 2002)" ed.). Chichester: John Wiley. pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-0-471-94829-2. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013.

Further reading

| Library resources about Mathematics |

- Benson, Donald C. (1999). The Moment of Proof: Mathematical Epiphanies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513919-8.

- Davis, Philip J.; Hersh, Reuben (1999). The Mathematical Experience (Reprint ed.). Boston; New York: Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-395-92968-1. Available online (registration required).

- Courant, Richard; Robbins, Herbert (1996). What Is Mathematics?: An Elementary Approach to Ideas and Methods (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510519-3.

- Gullberg, Jan (1997). Mathematics: From the Birth of Numbers. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04002-9.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2000). Encyclopaedia of Mathematics. Kluwer Academic Publishers. – A translated and expanded version of a Soviet mathematics encyclopedia, in ten volumes. Also in paperback and on CD-ROM, and online. Archived July 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- Jourdain, Philip E. B. (2003). "The Nature of Mathematics". In James R. Newman (ed.). The World of Mathematics. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43268-7.

- Pappas, Theoni (1986). The Joy Of Mathematics. San Carlos, California: Wide World Publishing. ISBN 978-0-933174-65-8.