Poultry

Poultry (/ˈpoʊltri/) are domesticated birds kept by humans for their eggs, their meat or their feathers.[1] These birds are most typically members of the superorder Galloanserae (fowl), especially the order Galliformes (which includes chickens, quails, and turkeys).[2] The term also includes birds that are killed for their meat, such as the young of pigeons (known as squabs) but does not include similar wild birds hunted for sport or food and known as game. The word "poultry" comes from the French/Norman word poule, itself derived from the Latin word pullus, which means small animal.[3]

The recent genomic study involving the four extant Junglefowl species reveal that the domestication of chicken, the most populous poultry species, occurred around 8,000 years ago in Southeast Asia.[4] Although this was believed to have occurred later around 5,400 years ago in Southeast Asia.[5] This may have originally been as a result of people hatching and rearing young birds from eggs collected from the wild, but later involved keeping the birds permanently in captivity. Domesticated chickens may have been used for cockfighting at first[6] and quail kept for their songs, but soon it was realised how useful it was having a captive-bred source of food. Selective breeding for fast growth, egg-laying ability, conformation, plumage and docility took place over the centuries, and modern breeds often look very different from their wild ancestors. Although some birds are still kept in small flocks in extensive systems, most birds available in the market today are reared in intensive commercial enterprises.

Together with pork, poultry is one of the two most widely eaten types of meat globally, with over 70% of the meat supply in 2012 between them;[7] poultry provides nutritionally beneficial food containing high-quality protein accompanied by a low proportion of fat. All poultry meat should be properly handled and sufficiently cooked in order to reduce the risk of food poisoning. Semi-vegetarians who consume poultry as the only source of meat are said to adhere to pollotarianism.

The word "poultry" comes from the West & English "pultrie", from Old French pouletrie, from pouletier, poultry dealer, from poulet, pullet.[8] The word "pullet" itself comes from Middle English pulet, from Old French polet, both from Latin pullus, a young fowl, young animal or chicken.[9][10] The word "fowl" is of Germanic origin (cf. Old English Fugol, German Vogel, Danish Fugl).[11]

Definition

"Poultry" is a term used for any kind of domesticated bird, captive-raised for its utility, and traditionally the word has been used to refer to wildfowl (Galliformes) and waterfowl (Anseriformes) but not to cagebirds such as songbirds and parrots. "Poultry" can be defined as domestic fowls, including chickens, turkeys, geese and ducks, raised for the production of meat or eggs and the word is also used for the flesh of these birds used as food.[8]

The Encyclopaedia Britannica lists the same bird groups but also includes guinea fowl and squabs (young pigeons).[12] In R. D. Crawford's Poultry breeding and genetics, squabs are omitted but Japanese quail and common pheasant are added to the list, the latter frequently being bred in captivity and released into the wild.[13] In his 1848 classic book on poultry, Ornamental and Domestic Poultry: Their History, and Management, Edmund Dixon included chapters on the peafowl, guinea fowl, mute swan, turkey, various types of geese, the muscovy duck, other ducks and all types of chickens including bantams.[14]

In colloquial speech, the term "fowl" is often used near-synonymously with "domesticated chicken" (Gallus gallus), or with "poultry" or even just "bird", and many languages do not distinguish between "poultry" and "fowl". Both words are also used for the flesh of these birds.[15] Poultry can be distinguished from "game", defined as wild birds or mammals hunted for food or sport, a word also used to describe the meat of these when eaten.[16]

Examples

| Bird | Wild ancestor | Domestication | Utilization | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken | Red junglefowl | Southeast Asia | Eggs and meat |  |

| Turkey | Wild turkey | Mexico | Meat |  |

| Japanese quail | Quail | Japan | Eggs and meat |  |

| Duck | Mallard | Various | Eggs and meat |  |

| Goose | Greylag | Various | Eggs and meat |  |

| Guinea fowl | Helmeted guinea fowl | Africa | Eggs and meat |  |

| Pigeon | Rock dove | Middle East | Meat |  |

Chickens

Chickens are medium-sized, chunky birds with an upright stance and characterised by fleshy red combs and wattles on their heads. Males, known as cocks, are usually larger, more boldly coloured, and have more exaggerated plumage than females (hens). Chickens are gregarious, omnivorous, ground-dwelling birds that in their natural surroundings search among the leaf litter for seeds, invertebrates, and other small animals. They seldom fly except as a result of perceived danger, preferring to run into the undergrowth if approached.[17] Today's domestic chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) is mainly descended from the wild red junglefowl of Asia, with some additional input from grey junglefowl, Sri Lankan junglefowl, and green junglefowl.[18][4]

Genomic studies estimate that the chicken was domesticated 8,000 years ago in Southeast Asia[4] and spread to China and India 2000–3000 years later. Archaeological evidence supports domestic chickens in Southeast Asia well before 6000 BC, China by 6000 BC and India by 2000 BC.[4][19][20] A landmark 2020 Nature study that fully sequenced 863 chickens across the world suggests that all domestic chickens originate from a single domestication event of red junglefowl whose present-day distribution is predominantly in southwestern China, northern Thailand and Myanmar. These domesticated chickens spread across Southeast and South Asia where they interbred with local wild species of junglefowl, forming genetically and geographically distinct groups. Analysis of the most popular commercial breed shows that the White Leghorn breed possesses a mosaic of divergent ancestries inherited from subspecies of red junglefowl.[21][22][23]

Chickens were one of the domesticated animals carried with the sea-borne Austronesian migrations into Taiwan, Island Southeast Asia, Island Melanesia, Madagascar, and the Pacific Islands; starting from around 3500 to 2500 BC.[24][25]

By 2000 BC, chickens seem to have reached the Indus Valley and 250 years later, they arrived in Egypt. They were still used for fighting and were regarded as symbols of fertility. The Romans used them in divination, and the Egyptians made a breakthrough when they learned the difficult technique of artificial incubation.[26] Since then, the keeping of chickens has spread around the world for the production of food with the domestic fowl being a valuable source of both eggs and meat.[27]

Since their domestication, a large number of breeds of chickens have been established, but with the exception of the white Leghorn, most commercial birds are of hybrid origin.[17] In about 1800, chickens began to be kept on a larger scale, and modern high-output poultry farms were present in the United Kingdom from around 1920 and became established in the United States soon after the Second World War. By the mid-20th century, the poultry meat-producing industry was of greater importance than the egg-laying industry. Poultry breeding has produced breeds and strains to fulfil different needs; light-framed, egg-laying birds that can produce 300 eggs a year; fast-growing, fleshy birds destined for consumption at a young age, and utility birds which produce both an acceptable number of eggs and a well-fleshed carcase. Male birds are unwanted in the egg-laying industry and can often be identified as soon as they are hatch for subsequent culling. In meat breeds, these birds are sometimes castrated (often chemically) to prevent aggression.[12] The resulting bird, called a capon, has more tender and flavorful meat, as well.[28]

A bantam is a small variety of domestic chicken, either a miniature version of a member of a standard breed, or a "true bantam" with no larger counterpart. The name derives from the town of Bantam in Java[29] where European sailors bought the local small chickens for their shipboard supplies. Bantams may be a quarter to a third of the size of standard birds and lay similarly small eggs. They are kept by small-holders and hobbyists for egg production, use as broody hens, ornamental purposes, and showing.[30]

Cockfighting

Cockfighting is said to be the world's oldest spectator sport. Two mature males (cocks or roosters) are set to fight each other, and will do so with great vigour until one is critically injured or killed. Cockfighting is extremely widespread in Island Southeast Asia, and often had ritual significance in addition to being a gambling sport.[25] They also formed part of the cultures of ancient India, China, Persia, Greece, Rome, and large sums were won or lost depending on the outcome of an encounter. Breeds such as the Aseel were developed in the Indian subcontinent for their aggressive behaviour.[31] Cockfighting has been banned in many countries during the last century on the grounds of cruelty to animals.[12]

Ducks

Ducks are medium-sized aquatic birds with broad bills, eyes on the side of the head, fairly long necks, short legs set far back on the body, and webbed feet. Males, known as drakes, are often larger than females (known as hens) and are differently coloured in some breeds. Domestic ducks are omnivores,[32]eating a variety of animal and plant materials such as aquatic insects, molluscs, worms, small amphibians, waterweeds, and grasses. They feed in shallow water by dabbling, with their heads underwater and their tails upended. Most domestic ducks are too heavy to fly, and they are social birds, preferring to live and move around together in groups. They keep their plumage waterproof by preening, a process that spreads the secretions of the preen gland over their feathers.[33]

Clay models of ducks found in China dating back to 4000 BC may indicate the domestication of ducks took place there during the Yangshao culture. Even if this is not the case, domestication of the duck took place in the Far East at least 1500 years earlier than in the West. Lucius Columella, writing in the first century BC, advised those who sought to rear ducks to collect wildfowl eggs and put them under a broody hen, because when raised in this way, the ducks "lay aside their wild nature and without hesitation breed when shut up in the bird pen". Despite this, ducks did not appear in agricultural texts in Western Europe until about 810 AD, when they began to be mentioned alongside geese, chickens, and peafowl as being used for rental payments made by tenants to landowners.[34]

It is widely agreed that the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) is the ancestor of all breeds of domestic duck (with the exception of the Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata), which is not closely related to other ducks).[34] Ducks are farmed mainly for their meat, eggs, and down.[35] As is the case with chickens, various breeds have been developed, selected for egg-laying ability, fast growth, and a well-covered carcase. The most common commercial breed in the United Kingdom and the United States is the Pekin duck, which can lay 200 eggs a year and can reach a weight of 3.5 kg (7 lb 11 oz) in 44 days.[33] In the Western world, ducks are not as popular as chickens, because the latter produce larger quantities of white, lean meat and are easier to keep intensively, making the price of chicken meat lower than that of duck meat. While popular in haute cuisine, duck appears less frequently in the mass-market food industry. However, things are different in the East. Ducks are more popular there than chickens and are mostly still herded in the traditional way and selected for their ability to find sufficient food in harvested rice fields and other wet environments.[35]

Geese

The greylag goose (Anser anser) was domesticated by the Egyptians at least 3000 years ago,[36] and a different wild species, the swan goose (Anser cygnoides), domesticated in Siberia about a thousand years later, is known as a Chinese goose.[37] The two hybridise with each other and the large knob at the base of the beak, a noticeable feature of the Chinese goose, is present to a varying extent in these hybrids. The hybrids are fertile and have resulted in several of the modern breeds. Despite their early domestication, geese have never gained the commercial importance of chickens and ducks.[36]

Domestic geese are much larger than their wild counterparts and tend to have thick necks, an upright posture, and large bodies with broad rear ends. The greylag-derived birds are large and fleshy and used for meat, while the Chinese geese have smaller frames and are mainly used for egg production. The fine down of both is valued for use in pillows and padded garments. They forage on grass and weeds, supplementing this with small invertebrates, and one of the attractions of rearing geese is their ability to grow and thrive on a grass-based system.[38] They are very gregarious and have good memories and can be allowed to roam widely in the knowledge that they will return home by dusk. The Chinese goose is more aggressive and noisy than other geese and can be used as a guard animal to warn of intruders.[36] The flesh of meat geese is dark-coloured and high in protein, but they deposit fat subcutaneously, although this fat contains mostly monounsaturated fatty acids. The birds are killed either around 10 or about 24 weeks. Between these ages, problems with dressing the carcase occur because of the presence of developing pin feathers.[38]

In some countries, geese and ducks are force-fed to produce livers with an exceptionally high fat content for the production of foie gras. Over 75% of world production of this product occurs in France, with lesser industries in Hungary and Bulgaria and a growing production in China.[39] Foie gras is considered a luxury in many parts of the world, but the process of feeding the birds in this way is banned in many countries on animal welfare grounds.[40]

Turkeys

Turkeys are large birds, their nearest relatives being the pheasant and the guineafowl. Males are larger than females and have spreading, fan-shaped tails and distinctive, fleshy wattles, called a snood, that hang from the top of the beak and are used in courtship display. Wild turkeys can fly, but seldom do so, preferring to run with a long, straddling gait. They roost in trees and forage on the ground, feeding on seeds, nuts, berries, grass, foliage, invertebrates, lizards, and small snakes.[41]

The modern domesticated turkey is descended from one of six subspecies of wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) found in the present Mexican states of Jalisco, Guerrero and Veracruz.[42] Pre-Aztec tribes in south-central Mexico first domesticated the bird around 800 BC, and Pueblo Indians inhabiting the Colorado Plateau in the United States did likewise around 200 BC. They used the feathers for robes, blankets, and ceremonial purposes. More than 1,000 years later, they became an important food source.[43] The first Europeans to encounter the bird misidentified it as a guineafowl, a bird known as a "turkey fowl" at that time because it had been introduced into Europe via Turkey.[41]

Commercial turkeys are usually reared indoors under controlled conditions. These are often large buildings, purpose-built to provide ventilation and low light intensities (this reduces the birds' activity and thereby increases the rate of weight gain). The lights can be switched on for 24 h/day, or a range of step-wise light regimens to encourage the birds to feed often and therefore grow rapidly. Females achieve slaughter weight at about 15 weeks of age and males at about 19. Mature commercial birds may be twice as heavy as their wild counterparts. Many different breeds have been developed, but the majority of commercial birds are white, as this improves the appearance of the dressed carcass, the pin feathers being less visible.[44] Turkeys were at one time mainly consumed on special occasions such as Christmas (10 million birds in the United Kingdom) or Thanksgiving (60 million birds in the United States). However, they are increasingly becoming part of the everyday diet in many parts of the world. [45]

Other poultry

Guineafowl originated in southern Africa, and the species most often kept as poultry is the helmeted guineafowl (Numida meleagris). It is a medium-sized grey or speckled bird with a small naked head with colorful wattles and a knob on top, and was domesticated by the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Guineafowl are hardy, sociable birds that subsist mainly on insects, but also consume grasses and seeds. They will keep a vegetable garden clear of pests and will eat the ticks that carry Lyme disease. They happily roost in trees and give a loud vocal warning of the approach of predators. Their flesh and eggs can be eaten in the same way as chickens, young birds being ready for the table at the age of about four months.[46]

A squab is the name given to the young of domestic pigeons that are destined for the table. Like other domesticated pigeons, birds used for this purpose are descended from the rock dove (Columba livia). Special utility breeds with desirable characteristics are used. Two eggs are laid and incubated for about 17 days. When they hatch, the squabs are fed by both parents on "pigeon's milk", a thick secretion high in protein produced by the crop. Squabs grow rapidly, but are slow to fledge and are ready to leave the nest at 26 to 30 days weighing about 500 g (1 lb 2 oz). By this time, the adult pigeons will have laid and be incubating another pair of eggs and a prolific pair should produce two squabs every four weeks during a breeding season lasting several months.[47]

Poultry farming

Worldwide, more chickens are kept than any other type of poultry, with over 50 billion birds being raised each year as a source of meat and eggs.[48] Traditionally, such birds would have been kept extensively in small flocks, foraging during the day and housed at night. This is still the case in developing countries, where the women often make important contributions to family livelihoods through keeping poultry. However, rising world populations and urbanization have led to the bulk of production being in larger, more intensive specialist units. These are often situated close to where the feed is grown or near to where the meat is needed, and result in cheap, safe food being made available for urban communities.[49] Profitability of production depends very much on the price of feed, which has been rising. High feed costs could limit further development of poultry production.[50]

In free-range husbandry, the birds can roam freely outdoors for at least part of the day. Often, this is in large enclosures, but the birds have access to natural conditions and can exhibit their normal behaviours. A more intensive system is yarding, in which the birds have access to a fenced yard and poultry house at a higher stocking rate. Poultry can also be kept in a barn system, with no access to the open air, but with the ability to move around freely inside the building. The most intensive system for egg-laying chickens is battery cages, often set in multiple tiers. In these, several birds share a small cage which restricts their ability to move around and behave in a normal manner. The eggs are laid on the floor of the cage and roll into troughs outside for ease of collection. Battery cages for hens have been illegal in the EU since January 1, 2012.[48]

Chickens raised intensively for their meat are known as "broilers". Breeds have been developed that can grow to an acceptable carcass size (2 kg or 4 lb 7 oz) in six weeks or less.[51] Broilers grow so fast, their legs cannot always support their weight and their hearts and respiratory systems may not be able to supply enough oxygen to their developing muscles. Mortality rates at 1% are much higher than for less-intensively reared laying birds which take 18 weeks to reach similar weights.[51] Processing the birds is done automatically with conveyor-belt efficiency. They are hung by their feet, stunned, killed, bled, scalded, plucked, have their heads and feet removed, eviscerated, washed, chilled, drained, weighed, and packed,[52] all within the course of little over two hours.[51]

Both intensive and free-range farming have animal welfare concerns. In intensive systems, cannibalism, feather pecking and vent pecking can be common, with some farmers using beak trimming as a preventative measure.[53] Diseases can also be common and spread rapidly through the flock. In extensive systems, the birds are exposed to adverse weather conditions and are vulnerable to predators and disease-carrying wild birds. Barn systems have been found to have the worst bird welfare.[53] In Southeast Asia, a lack of disease control in free-range farming has been associated with outbreaks of avian influenza.[54]

Poultry shows

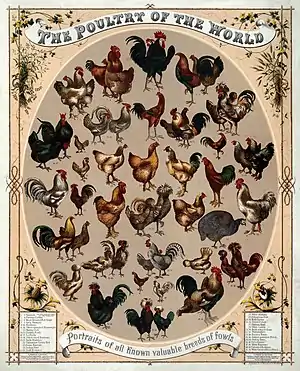

In many countries, national and regional poultry shows are held where enthusiasts exhibit their birds which are judged on certain phenotypical breed traits as specified by their respective breed standards. The idea of poultry exhibition may have originated after cockfighting was made illegal, as a way of maintaining a competitive element in poultry husbandry. Breed standards were drawn up for egg-laying, meat-type, and purely ornamental birds, aiming for uniformity.[55] Sometimes, poultry shows are part of general livestock shows, and sometimes they are separate events such as the annual "National Championship Show" in the United Kingdom organised by the Poultry Club of Great Britain.[56]

Poultry as food

Trade

Poultry is the second most widely eaten type of meat in the world, accounting for about 30% of total meat production worldwide compared to pork at 38%. Sixteen billion birds are raised annually for consumption, more than half of these in industrialised, factory-like production units.[57] Global broiler meat production rose to 84.6 million tonnes in 2013. The largest producers were the United States (20%), China (16.6%), Brazil (15.1%) and the European Union (11.3%).[58] There are two distinct models of production; the European Union supply chain model seeks to supply products which can be traced back to the farm of origin. This model faces the increasing costs of implementing additional food safety requirements, welfare issues and environmental regulations. In contrast, the United States model turns the product into a commodity.[59]

World production of duck meat was about 4.2 million tonnes in 2011 with China producing two thirds of the total,[60] some 1.7 billion birds. Other notable duck-producing countries in the Far East include Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar, Indonesia and South Korea (12% in total). France (3.5%) is the largest producer in the West, followed by other EU nations (3%) and North America (1.7%).[34] China was also by far the largest producer of goose and guinea fowl meat, with a 94% share of the 2.6 million tonne global market.[60]

Global egg production was expected to reach 65.5 million tonnes in 2013, surpassing all previous years.[61] Between 2000 and 2010, egg production was growing globally at around 2% per year, but since then growth has slowed down to nearer 1%.[61]

Cuts of poultry

Poultry is available fresh or frozen, as whole birds or as joints (cuts), bone-in or deboned, seasoned in various ways, raw or ready cooked.[62] The meatiest parts of a bird are the flight muscles on its chest, called "breast" meat, and the walking muscles on the legs, called the "thigh" and "drumstick". The wings are also eaten (Buffalo wings are a popular example in the United States) and may be split into three segments, the meatier "drumette", the "wingette" (also called the "flat"), and the wing tip (also called the "flapper").[62][63] In Japan, the wing is frequently separated, and these parts are referred to as 手羽元 (teba-moto "wing base") and 手羽先 (teba-saki "wing tip").[64]

Dark meat, which avian myologists refer to as "red muscle", is used for sustained activity—chiefly walking, in the case of a chicken. The dark color comes from the protein myoglobin, which plays a key role in oxygen uptake and storage within cells. White muscle, in contrast, is suitable only for short bursts of activity such as, for chickens, flying. Thus, the chicken's leg and thigh meat are dark, while its breast meat (which makes up the primary flight muscles) is white. Other birds with breast muscle more suitable for sustained flight, such as ducks and geese, have red muscle (and therefore dark meat) throughout.[65] Some cuts of meat including poultry expose the microscopic regular structure of intracellular muscle fibrils which can diffract light and produce iridescent colors, an optical phenomenon sometimes called structural coloration.[66]

Health and disease (humans)

Poultry meat and eggs provide nutritionally beneficial food containing protein of high quality. This is accompanied by low levels of fat which have a favourable mix of fatty acids.[67] Chicken meat contains about two to three times as much polyunsaturated fat as most types of red meat when measured by weight.[68] However, for boneless, skinless chicken breast, the amount is much lower. A 100-g serving of baked chicken breast contains 4 g of fat and 31 g of protein, compared to 10 g of fat and 27 g of protein for the same portion of broiled, lean skirt steak.[69][70]

A 2011 study by the Translational Genomics Research Institute showed that 47% of the meat and poultry sold in United States grocery stores was contaminated with Staphylococcus aureus, and 52% of the bacteria concerned showed resistance to at least three groups of antibiotics. Thorough cooking of the product would kill these bacteria, but a risk of cross-contamination from improper handling of the raw product is still present.[71] Also, some risk is present for consumers of poultry meat and eggs to bacterial infections such as Salmonella and Campylobacter. Poultry products may become contaminated by these bacteria during handling, processing, marketing, or storage, resulting in food-borne illness if the product is improperly cooked or handled.[67]

In general, avian influenza is a disease of birds caused by bird-specific influenza A virus that is not normally transferred to people; however, people in contact with live poultry are at the greatest risk of becoming infected with the virus and this is of particular concern in areas such as Southeast Asia, where the disease is endemic in the wild bird population and domestic poultry can become infected. The virus possibly could mutate to become highly virulent and infectious in humans and cause an influenza pandemic.[72]

Bacteria can be grown in the laboratory on nutrient culture media, but viruses need living cells in which to replicate. Many vaccines to infectious diseases can be grown in fertilised chicken eggs. Millions of eggs are used each year to generate the annual flu vaccine requirements, a complex process that takes about six months after the decision is made as to what strains of virus to include in the new vaccine. A problem with using eggs for this purpose is that people with egg allergies are unable to be immunised, but this disadvantage may be overcome as new techniques for cell-based rather than egg-based culture become available.[73] Cell-based culture will also be useful in a pandemic when it may be difficult to acquire a sufficiently large quantity of suitable sterile, fertile eggs.[74]

See also

- Gamebird

- Poultry allergy

- Virulent Newcastle disease

References

- "Consider These 6 Types Of Poultry For Your Farm". Hobby Farms. August 14, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "Fowl". HowStuffWorks. April 22, 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "Our Poultry". Poule D'or Chicken. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- Lawal, Raman Akinyanju; Martin, Simon H.; Vanmechelen, Koen; Vereijken, Addie; Silva, Pradeepa; Al-Atiyat, Raed Mahmoud; Aljumaah, Riyadh Salah; Mwacharo, Joram M.; Wu, Dong-Dong; Zhang, Ya-Ping; Hocking, Paul M.; Smith, Jacqueline; Wragg, David; Hanotte, Olivier (December 2020). "The wild species genome ancestry of domestic chickens". BMC Biology. 18 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s12915-020-0738-1. PMC 7014787. PMID 32050971.

- Killgrove, Kristina. "Ancient DNA Explains How Chickens Got To The Americas". Forbes. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "Chickens Were Initially Domesticated for Cockfighting, Not Food". Today I Found Out. August 30, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "Sources of the world's meat supply in 2012". FAO. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- "Poultry". The American Heritage: Dictionary of the English Language. Vol. 4th edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2009.

- "Pullet". The American Heritage: Dictionary of the English Language. Vol. 4th edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2009.

- "Fowl". Online Etymology Dictionary. Etymonline.com. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "Poultry". Online Etymology Dictionary. Ehitymonline.com. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "Poultry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. June 6, 2013.

- Crawford, R. D. (1990). Poultry Breeding and Genetics. Elsevier. p. 1. ISBN 0-444-88557-9.

- Dixon, Rev Edmund Saul (1848). Ornamental and Domestic Poultry: Their History, and Management. Gardeners' Chronicle. p. 1.

poultry history.

- "Fowl". The Free Dictionary. thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "Game". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- Card, Leslie E. (1961). Poultry Production. Lea & Febiger. ISBN 978-0-8121-1241-2.

- Eriksson, Jonas; Larson, Greger; Gunnarsson, Ulrika; Bed'hom, Bertrand; Tixier-Boichard, Michele; Strömstedt, Lina; Wright, Dominic; Eriksson J, Larson G, Gunnarsson U, Bed'hom B, Tixier-Boichard M; Vereijken, Addie; Randi, Ettore; Jensen, Per; Andersson, Leif; et al. (2008), "Identification of the yellow skin gene reveals a hybrid origin of the domestic chicken", PLOS Genetics, 4 (2): e1000010, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000010, PMC 2265484, PMID 18454198

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - West, B.; Zhou, B.X. (1988). "Did chickens go north? New evidence for domestication". J. Archaeol. Sci. 14 (5): 515–533. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(88)90080-5.

- Al-Nasser, A.; Al-Khalaifa, H.; Al-Saffar, A.; Khalil, F.; Albahouh, M.; Ragheb, G.; Al-Haddad, A.; Mashaly, M. (June 1, 2007). "Overview of chicken taxonomy and domestication". World's Poultry Science Journal. 63 (2): 285–300. doi:10.1017/S004393390700147X. S2CID 86734013.

- Wang, Ming-Shan; et al. (2020). "863 genomes reveal the origin and domestication of chicken". Cell Research. 30 (8): 693–701. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0349-y. PMC 7395088. PMID 32581344. S2CID 220050312.

- Liu, Yi-Ping; Wu, Gui-Sheng; Yao, Yong-Gang; Miao, Yong-Wang; Luikart, Gordon; Baig, Mumtaz; Beja-Pereira, Albano; Ding, Zhao-Li; Palanichamy, Malliya Gounder; Zhang, Ya-Ping (January 2006). "Multiple maternal origins of chickens: Out of the Asian jungles". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 38 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.014. PMID 16275023.

- Zeder, Melinda A.; Emshwiller, Eve; Smith, Bruce D.; Bradley, Daniel G. (March 2006). "Documenting domestication: the intersection of genetics and archaeology". Trends in Genetics. 22 (3): 139–155. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.007. PMID 16458995.

- Piper, Philip J. (2017). "The Origins and Arrival of the Earliest Domestic Animals in Mainland and Island Southeast Asia: A Developing Story of Complexity". In Piper, Philip J.; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Bulbeck, David (eds.). New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory. terra australis. Vol. 45. ANU Press. ISBN 9781760460945.

- Blust, Robert (June 2002). "The History of Faunal Terms in Austronesian Languages". Oceanic Linguistics. 41 (1): 89–139. doi:10.2307/3623329. JSTOR 3623329.

- Adler, Jerry; Lawler, Andrew (June 1, 2012). "How the Chicken Conquered the World". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- Storey, A. A.; Athens, J. S.; Bryant, D.; Carson, M.; Emery, K.; et al. (2012). "Investigating the global dispersal of chickens in prehistory using ancient mitochondrial DNA signatures". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e39171. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...739171S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039171. PMC 3405094. PMID 22848352.

- Mrs A Basley (1910). Western poultry book. Mrs. A. Basley. pp. 112–15.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- "Breed gallery". The Poultry Club of Great Britain. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- Nadeem Ullah. "History of Aseel". Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- "10 Facts About Ducks". FOUR PAWS International - Animal Welfare Organisation. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- "Information sheet: The Welfare of Farmed Ducks". RSPCA. July 1, 2012. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- Cherry, Peter; Morris, T. R. (2008). Domestic Duck Production: Science and Practice. CABI. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-1-84593-441-5.

- Dean, William F.; Sandhu, Tirath S. (2008). "Domestic ducks". Cornell University. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Buckland, R.; Guy, G. "Origins and Breeds of Domestic Geese". FAO Agriculture Department. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- Streit, Scott (2000). "White Chinese Goose". Bird Friends Of San Diego County. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- "CALU factsheet: Meat geese seasonal production" (PDF). June 1, 2009. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- Mo Hong'e (April 11, 2006). "China to boost foie gras production". China View. Archived from the original on June 2, 2007. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- "Welfare Aspects of the Production of Foie Gras in Ducks and Geese" (PDF). Report of the Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare. December 16, 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 19, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- Smith, Andrew F. (2006). The Turkey: An American Story. University of Illinois Press. pp. 4–5, 17. ISBN 978-0-252-03163-2.

turkey bird name.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Wild turkey: Meleagris gallopavo, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. L Stromberg Archived July 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Viegas, Jennifer (February 1, 2010). "Native Americans First Tamed Turkeys 2,000 Years Ago". Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- Pond, Wilson, G.; Bell, Alan, W. (eds.) (2010). Turkeys: Behavior, Management and Well-Being. Marcell Dekker. pp. 847–849. ISBN 978-0-8247-5496-9.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Bill, Joe (December 18, 2013). "Can turkey rule the roost all year round?". Your Shepway. Archived from the original on March 3, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Jacob, Jacquie; Pescatore, Tony; Cantor, Austin. "Keeping Guinea fowl" (PDF). University of Kentucky. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- Bolla, Gerry (April 1, 2007). "Primefacts: Squab raising" (PDF). Primefacts. NSW Department of Primary Industries. ISSN 1832-6668. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- "Compassion in World Farming: Poultry". Ciwf.org.uk. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "Animal production and health: Poultry". FAO. September 25, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- Agritrade. "Poultry Brief 2013". CTA. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- Browne, Anthony (March 10, 2002). "Ten weeks to live". The Guardian. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- "Meat chicken farm sequence (processing)". Poultry Hub. August 20, 2010. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- Sherwin, C. M.; Richards, G. J; Nicol, C. J. (2010). "A comparison of the welfare of layer hens in four housing systems in the UK". British Poultry Science. 51 (4): 488–499. doi:10.1080/00071668.2010.502518. PMID 20924842. S2CID 8968010.

- "Free-range farming and avian flu in Asia" (PDF). WSPA International. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 16, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "History of poultry". Poultry Club of Great Britain. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- "Types of Show". Poultry Club of Great Britain. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- Raloff, Janet. Food for Thought: Global Food Trends. Science News Online. May 31, 2003.

- "USDA Livestock & Poultry: World Markets & Trade". The Poultry Site. April 30, 2013. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- Manning, Louise; Baines, R. N.; Chadd, S. A. (2007). "Trends in the global poultry meat supply chain". British Food Journal. 109 (5): 332–342. doi:10.1108/00070700710746759.

- "USDA International Livestock & Poultry: World Duck, Goose and Guinea Fowl Meat Situation". The Poultry Site. December 19, 2013. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- "Global Poultry Trends: World Egg Production Sets a Record Despite Slower Growth". The Poultry Site. January 16, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "Poultry meat cuts". FeedCo USA. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- "America, You're Getting Two-Thirds of the Hot Wing". Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Hosking, Richard (1996). 日本料理用語辞典 (英文): Ingredients & Culture. Tuttle Publishing. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8048-2042-4.

- "The color of meat and poultry". USDA: Food Safety and Inspection Service. May 1, 2000. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- Martinez-Hurtado, J. L. (2013). "Iridescence in Meat Caused by Surface Gratings". Foods. 2 (4): 499–506. doi:10.3390/foods2040499. hdl:10149/597186. PMC 5302279. PMID 28239133.

- "Poultry and human health". FAO. August 1, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- "Feinberg School: Nutrition Fact Sheet: Lipids". Northwestern University. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- "Nutrition Data - 100g Chicken Breast".

- "Nutrition Data - 100g Lean Skirt Steak".

- The Translational Genomics Research Institute (April 15, 2011). "US meat and poultry is widely contaminated with drug-resistant Staph bacteria, study finds". Science Daily. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- "Information on Avian Influenza". Seasonal Influenza (Flu). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- "The evolution, and revolution, of flu vaccines". FDA: Consumer updates. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. January 18, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- "Vaccines for pandemic threats". The History of Vaccines. January 15, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.