Goose

A goose (PL: geese) is a bird of any of several waterfowl species in the family Anatidae. This group comprises the genera Anser (the grey geese and white geese) and Branta (the black geese). Some other birds, mostly related to the shelducks, have "goose" as part of their names. More distantly related members of the family Anatidae are swans, most of which are larger than true geese, and ducks, which are smaller.

.jpg.webp)

The term "goose" may refer to either a male or female bird, but when paired with "gander", refers specifically to a female one (the latter referring to a male). Young birds before fledging are called goslings.[1] The collective noun for a group of geese on the ground is a gaggle; when in flight, they are called a skein, a team, or a wedge; when flying close together, they are called a plump.[2]

Etymology

The word "goose" is a direct descendant of,*ghans-. In Germanic languages, the root gave Old English gōs with the plural gēs and gandres (becoming Modern English goose, geese, gander, and gosling, respectively), Frisian goes, gies and guoske, New High German Gans, Gänse, and Ganter, and Old Norse gās.

This term also gave Lithuanian: žąsìs, Irish: gé (goose, from Old Irish géiss), Hindi: कलहंस, Latin: anser, Spanish: ganso, Ancient Greek: χήν (khēn), Dutch: gans, Albanian: gatë swans), Finnish: hanhi, Avestan zāō, Polish: gęś, Romanian: gâscă / gânsac, Ukrainian: гуска / гусак (huska / husak), Russian: гусыня / гусь (gusyna / gus), Czech: husa, and Persian: غاز (ghāz).[1][3]

True geese and their relatives

The two living genera of true geese are: Anser, grey geese and white geese, such as the greylag goose and snow goose, and Branta, black geese, such as the Canada goose.

Two genera of geese are only tentatively placed in the Anserinae; they may belong to the shelducks or form a subfamily on their own: Cereopsis, the Cape Barren goose, and Cnemiornis, the prehistoric New Zealand goose. Either these or, more probably, the goose-like coscoroba swan is the closest living relative of the true geese.

Fossils of true geese are hard to assign to genus; all that can be said is that their fossil record, particularly in North America, is dense and comprehensively documents many different species of true geese that have been around since about 10 million years ago in the Miocene. The aptly named Anser atavus (meaning "progenitor goose") from some 12 million years ago had even more plesiomorphies in common with swans. In addition, some goose-like birds are known from subfossil remains found on the Hawaiian Islands.

Geese are monogamous, living in permanent pairs throughout the year; however, unlike most other permanently monogamous animals, they are territorial only during the short nesting season. Paired geese are more dominant and feed more, two factors that result in more young.[4][5]

Geese honk while in flight to encourage other members of the flock to maintain a 'v-formation' and to help communicate with one another.[6]

Fossil record

Geese fossils have been found ranging from 10 to 12 million years ago (Middle Miocene). Garganornis ballmanni from Late Miocene (~ 6-9 Ma) of Gargano region of central Italy, stood one and a half meters tall and weighed about 22 kilograms. The evidence suggests the bird was flightless, unlike modern geese.[7]

Migratory patterns

Geese like the Canada goose do not always migrate.[8] Some members of the species only move south enough to ensure a supply of food and water. When European settlers came to America, the birds were seen as easy prey and were almost wiped out of the population. The species was reintroduced across the northern U.S. range and their population has been growing ever since.[9]

Preparation

Geese typically migrate in the fall and in order to prepare for this travel they start in the summer by igniting a process called molting. A process where the birds shed their old feathers and grow new ones to prepare for the journey ahead. During the process of molting, geese are unable to fly and tend to reside in the water for protection. Baby geese that are born in the spring are typically ready for travel by the time fall comes around. Much like how animals who hibernate, geese eat more during the time they prepare for migration.[10]

Navigation

Migratory geese, unlike other migratory birds, wait until their environment is no longer supplementing them with resources before they decide to travel. In order to travel, geese remember landmarks as well as use the sun and the moon, and past experience to navigate their journey. For orientation, geese use earth's magnetic field. Different flocks in the same area typically travel along the same path. They do not travel nonstop, they take breaks at common landmarks for other flocks to gain fat that was lost during flying. Geese have to adjust and accommodate their migration habits for changes in the environment, they must remain flexible.[10] In just 24 hours the most commonly seen migratory goose, the Canada goose, can travel 1,500 miles.[9]

Formation

Geese, like other birds, fly in a V formation. During flight, communication between each bird is important and the V formation can make that easier. They use this technique for two reasons, to slow down energy loss and to keep track of every bird in the formation.[11] The birds in the back of the formation use pockets of air from the movement of the birds in front to help keep them aloft. Each bird takes a turn in the front of the formation to ensure longer flights with fewer stops. Taking turns allows the birds at the front of the formation to take rests. Typically it is older birds in the front of the formation and younger birds in the back. The placement of the birds and their movements during flying are very important in how this formation works.[12]

Other birds called "geese"

Some mainly Southern Hemisphere birds are called "geese", most of which belong to the shelduck subfamily Tadorninae. These are:

- The Orinoco goose (Neochen jubata)

- The Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiaca)

- The South American sheldgeese in the genus Chloephaga

- The prehistoric Malagasy sheldgoose (Centrornis majori)

Others:

- The spur-winged goose (Plectropterus gambensis) is most closely related to the shelducks, but distinct enough to warrant its own subfamily, the Plectropterinae.

- The blue-winged goose (Cyanochen cyanopterus) and the Cape Barren goose (Cereopsis novaehollandiae) have disputed affinities. They belong to separate ancient lineages that may ally either to the Tadorninae, the Anserinae, or closer to the dabbling ducks (Anatinae).

- The three species of small waterfowl in the genus Nettapus named "pygmy geese"; they seem to represent another ancient lineage, with possible affinities to the Cape Barren goose or the spur-winged goose.

- The maned goose, also known as the maned duck or Australian wood duck (Chenonetta jubata)

- A genus of prehistorically extinct seaducks, Chendytes, is sometimes called the "diving-geese" due to their large size.[13]

- The magpie goose (Anseranas semipalmata) is the only living species in the family Anseranatidae.

- The northern gannet (Morus bassanus), a seabird, is also known as the "solan goose", although it is unrelated to the true geese, or any other Anseriformes for that matter.

In popular culture

Well-known sayings about geese include:

- To "have a gander" is to look at something.

- "What's good sauce for the goose is good sauce for the gander" or "What's good for the goose is good for the gander" means that what is an appropriate treatment for one person is equally appropriate for someone else. This statement supporting equality is frequently used in the context of sex and gender, because a goose is female and a gander is male.[14]

- Saying that someone's "goose is cooked" means that they are about to be punished.[14]

- The common phrase "silly goose" is used when referring to someone who is acting particularly silly.[14]

- "Killing the goose that lays the golden eggs", derived from Aesop's Fables, is a saying referring to a greed-motivated action that destroys or otherwise renders useless a favourable situation that would have provided benefits over time.[14]

- "A wild goose chase" is a useless, futile waste of time and effort. It is derived from a 16th-century horse racing event.[14]

- There is a legendary old woman called Mother Goose who wrote nursery rhymes for children.

- A raised, rounded area of swelling (typically a hematoma) caused by an impact injury is sometimes metaphorically called a "goose egg", especially if it occurs on the head.[15]

"Gray Goose Laws" in Iceland

The oldest collection of Medieval Icelandic laws is known as "Grágás"; i.e., the Gray Goose Laws.

Various etymologies were offered for that name:

Gallery

Canada goose gosling

Canada goose gosling Canada geese in flight, Great Meadows Wildlife Sanctuary

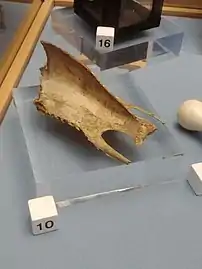

Canada geese in flight, Great Meadows Wildlife Sanctuary Goose breastbone, the colour of the bones after cooking was used to predict how cold winter would be in Lincolnshire folkloric traditions (North Lincolnshire Museum)

Goose breastbone, the colour of the bones after cooking was used to predict how cold winter would be in Lincolnshire folkloric traditions (North Lincolnshire Museum)

See also

- Angel wing, a disease common in geese

- Domestic goose, which includes cooking and folklore

- Flying geese paradigm

- List of Anseriformes by population

- List of goose breeds

- Roast goose

- Waterfowl

- Wildfowl

- Untitled Goose Game, a video game centering around a goose that takes place in a middle-class village in England.

References

- Partridge, Eric (1983). Origins: a Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. New York: Greenwich House. pp. 245–246. ISBN 0-517-414252.

- "AskOxford: G". Collective Terms for Groups of Animals. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- Crystal, David (1998). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. ISBN 0-521-55967-7.

- Lamprecht, Jürg (1987). "Female reproductive strategies in bar-headed geese (Anser indicus): Why are geese monogamous?". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. Springer. 21 (5): 297–305. doi:10.1007/BF00299967. S2CID 34973918.

- "Canada Goose". National Geographic. 10 May 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Interesting facts about geese". justfunfacts.com. 7 March 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Yirka, Bob (2017). "Fossils from ancient extinct giant flightless goose suggests it was a fighter". phys.org. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Do Canada geese still fly south for winter? Yes, but it's complicated". Animals. 2020-12-16. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- "Do Canada geese still fly south for winter? Yes, but it's complicated". Animals. 2020-12-16. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- Langen, Tom. "How do geese know how to fly south for the winter?". The Conversation. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- "Why do geese fly in a V?". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- "Birds That Fly in a V Formation Use An Amazing Trick". Science. 2014-01-15. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- Howard, Hildegarde (1955). "New Records and a New Species of Chendytes, an Extinct Genus of Diving Geese". The Condor. 57 (3): 135–143. doi:10.2307/1364861. JSTOR 1364861.

- Warhol, Tom; Schneck, Marcus (2010-10-01). Birdwatcher's Daily Companion: 365 Days of Advice, Insight, and Information for Enthusiastic Birders. Quarry Books. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-61059-399-1.

- Roland, James. "What’s Causing This Bump on My Forehead, and Should I Be Concerned?" HealthLine, 2 August 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2020. https://www.healthline.com/health/bump-on-forehead

- Boulhosa, Patricia Press. “The Law of Óláfr inn Helgi.” In Icelanders and the Kings of Norway: Mediaeval Sagas and Legal Texts. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2005.

- Byock, Jesse L., Medieval Iceland: Society, Sagas, and Power, Berkeley: University of California, 1990

- Byock, Jesse L. "Grágás: The 'Grey Goose' Law in Viking Age Iceland London: Penguin, 2001.

Further reading

- Carboneras, Carles (1992). "Family Anatidae (Ducks, Geese and Swans)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.). Handbook of Birds of the World. Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. pp. 536–629. ISBN 84-87334-10-5.

- Terres, John K.; National Audubon Society (1991) [1980]. The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York: Wings Books. ISBN 0-517-03288-0.

External links

- Anatidae media on the Internet Bird Collection