Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union[lower-alpha 1] was the executive leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, acting between sessions of Congress. According to party statutes, the committee directed all party and governmental activities. Its members were elected by the Party Congress.

| |

| Information | |

|---|---|

| General Secretary | Joseph Stalin |

| Elected by | Congress |

| Responsible to | Congress |

| Child organs |

|

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Grand Kremlin Palace, Moscow Kremlin[1][2][3] | |

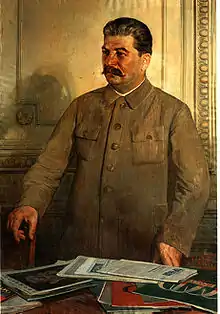

During Vladimir Lenin's leadership of the Communist Party, the Central Committee functioned as the highest party authority between Congresses. However, in the following decades the de facto most powerful decision-making body would oscillate back and forth between the Central Committee and the Political Bureau or Politburo (and during Joseph Stalin, the Secretariat). Some committee delegates objected to the re-establishment of the Politburo in 1919, and in response, the Politburo became organizationally responsible to the Central Committee. Subsequently, the Central Committee members could participate in Politburo sessions with a consultative voice, but could not vote unless they were members. Following Lenin's death in January 1924, Stalin gradually increased his power in the Communist Party through the office of General Secretary of the Central Committee, the leading Secretary of the Secretariat. With Stalin's takeover, the role of the Central Committee was eclipsed by the Politburo, which consisted of a small clique of loyal Stalinists.

By the time of Stalin's death in 1953, the Central Committee had become largely a symbolic organ that was responsible to the Politburo, and not the other way around. The death of Stalin revitalised the Central Committee, and it became an important institution during the power struggle to succeed Stalin. Following Nikita Khrushchev's accession to power, the Central Committee still played a leading role; it overturned the Politburo's decision to remove Khrushchev from office in 1957. In 1964 the Central Committee ousted Khrushchev from power and elected Leonid Brezhnev as First Secretary. The Central Committee was an important organ in the beginning of Brezhnev's rule, but lost effective power to the Politburo. From then on, until the era of Mikhail Gorbachev (General Secretary from 1985 to 1991), the Central Committee played a minor role in the running of the party and state – the Politburo once again operated as the highest political organ in the Soviet Union.

For the majority of Central Committee's history, plenums were held in the meeting chamber of the Soviet of the Union in the Grand Kremlin Palace. The offices of the administrative staff of the Central Committee were located in the 4th building of Staraya Square in Moscow, in what is now the Russian Presidential Administration Building.

History

Background: 1898–1917

At the founding congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (the predecessor of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) Vladimir Lenin was able to gain enough support for the establishment of an all-powerful central organ at the next congress.[4] This central organ was to become the Central Committee, and it had the rights to decide all party issues, with the exception of local ones.[4] The group which supported the establishment of a Central Committee at the 2nd Congress called themselves the Bolsheviks, and the losers (the minority) were given the name Mensheviks by their own leader, Julius Martov.[5] The Central Committee would contain three members, and would supervise the editorial board of Iskra, the party newspaper.[5] The first members of the Central Committee were Gleb Krzhizhanovsky, Friedrich Lengnik and Vladimir Noskov.[5] Throughout its history, the party and the Central Committee were riven by factional infighting and repression by government authorities.[6] Lenin was able to persuade the Central Committee, after a long and heated discussion, to initiate the October Revolution.[6] The majority of the members had been skeptical of initiating the revolution so early, and it was Lenin who was able to persuade them.[6] The motion to carry out a revolution in October 1917 was passed with 10 in favour, and two against by the Central Committee.[6]

Lenin era: 1917–1922

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

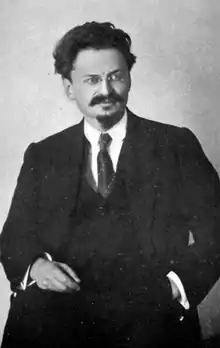

The Central Committee, according to Lenin, was to be the supreme authority of the party.[7] Long before he joined forces with Lenin and became the Soviet military leader, Leon Trotsky had once criticised this view, stating "our rules represent 'organisational nonconfidence' of the party toward its parts, that is, supervision over all local, district, national and other organisations ... the organisation of the party takes place of the party itself; the Central Committee takes the place of the organisation; and finally the dictator takes the place of the Central Committee."[8]

During the first years in power, under Lenin's rule, the Central Committee was the key decision-making body in both practice and theory, and decisions were made through majority votes.[9] For example, the Central Committee voted for or against signing a peace treaty with the Germans between 1917 and 1918 during World War I; the majority voted in favour of peace when Trotsky backed down in 1918.[9] The result of the vote was the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.[9] During the heated debates in the Central Committee about a possible peace with the Germans, Lenin did not have a majority; both Trotsky and Nikolai Bukharin had more support for their own position than Lenin.[10] Only when Lenin sought a coalition with Trotsky and others, were negotiations with the Germans voted through with a simple majority.[10] Criticism of other officials was allowed during these meetings, for instance, Karl Radek said to Lenin (criticising his position of supporting peace with the Germans), "If there were five hundred courageous men in Petrograd, we would put you in prison."[11] The decision to negotiate peace with the Germans was only reached when Lenin threatened to resign, which in turn led to a temporary coalition between Lenin's supporters and those of Trotsky and others.[11] No sanctions were invoked on the opposition in the Central Committee following the decision.[11]

The system had many faults, and opposition to Lenin and what many saw as his excessive centralisation policies came to the leadership's attention during the 8th Party Congress (March 1919) and the 9th Party Congress (March 1920).[12] At the 9th Party Congress the Democratic Centralists, an opposition faction within the party, accused Lenin and his associates, of creating a Central Committee in which a "small handful of party oligarchs ... was banning those who hold deviant views."[13] Several delegates to the Congress were quite specific in the criticism, one of them accusing Lenin and his associates of making the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic a place of exile for opponents.[13] Lenin reply was evasive, he conceded that faults had been made, but noted that if such policies had in fact been carried out the criticism of him during the 9th Party Congress could not have occurred.[13] During the 10th Party Congress (March 1921) Lenin condemned the Workers Opposition, a faction within the Communist Party, for deviating from communism.[14] Lenin did state that factionalism was allowed, but only allowed before and during Party Congresses when the different sides needed to win votes.[15] Several Central Committee members, who were members of the Workers Opposition, offered their resignation to Lenin but their resignations were not accepted, and they were instead asked to submit to party discipline.[15] The 10th Party Congress also introduced a ban on factionalism within the Communist Party; however, what Lenin considered to be 'platforms', such as the Democratic Centralists and the Workers Opposition, were allowed.[14] Factions, in Lenin's mind, were groups within the Communist Party who subverted party discipline.[14]

Despite the ban on factionalism, the Workers' Opposition continued its open agitation against the policies of the Central Committee, and before the 11th Party Congress (March 1922) the Workers' Opposition made an ill-conceived bid to win support for their position in the Comintern.[16] The Comintern, not unexpectedly, supported the position of the Central Committee.[16] During the 11th Party Congress Alexander Shliapnikov, the leader of the Workers' Opposition, claimed that certain individuals from the Central Committee had threatened him.[17] Lenin's reply was evasive, but he stated that party discipline needed to be strengthened during "a retreat" – the New Economic Policy was introduced at the 10th Party Congress.[17] The 11th Party Congress would prove to be the last congress chaired by Lenin, he suffered one stroke in May 1922, was paralysed by a second in December later that year, was removed from public life in March 1923 and died on 21 January 1924.[18]

Interregnum: 1922–1930

When Lenin died, the Soviet leadership was uncertain how the building of the new, socialist society should proceed.[19] Some supported extending the NEP, as Lenin had suggested late in his life, or ending it and replacing it with a planned economy, a position Lenin held when he initiated NEP.[19] Following Lenin's forced departure due to ill health, a power struggle began, which involved Nikolai Bukharin, Lev Kamenev, Alexei Rykov, Joseph Stalin, Mikhail Tomsky, Leon Trotsky and Grigory Zinoviev.[20] Of these, Trotsky was the most notable one.[20] In his testament, Lenin referred to Trotsky's "exceptional abilities", adding "personally he is perhaps the most able man in the present central committee."[20] Trotsky did face a problem however: he had previously disagreed with Lenin on several matters.[21] He was also of Jewish descent.[22]

Stalin, the second major contender, and future leader of the Soviet Union, was the least known, and he was not a popular figure with the masses.[22] Even though he was a Georgian, and he opposed Georgian nationalism, he talked like a Slavophile, which was an advantage.[23] The Communist Party was his institutional base; he was the General Secretary – another advantage.[23] But there was a problem; Stalin was known for his brutality.[23] As one Party faithful put it, "A savage man ... a bloody man. You have to have swords like him in a revolution but I don't like that fact, nor like him."[23] In his testament, Lenin said of Stalin:[24]

Stalin is too rude, and this fault, fully tolerable in our midst and in the relations among us Communists, becomes intolerable in the office of General Secretary. Therefore I propose to the comrades that they devise a way of shifting Stalin from this position and appointing to it another man who in all other respects falls on the other side of the scale from Comrade Stalin, namely, more tolerant, more loyal, more polite and considerate of comrades, less capricious and so forth.

Inner-party democracy became an important topic following Lenin's health leave; Trotsky and Zinoviev were its main backers, but Zinoviev later changed his position when he aligned himself with Stalin.[25] Trotsky and Rykov tried to reorganise the party in early 1923, by debureaucratising it, however, in this they failed, and Stalin managed to enlarge the Central Committee.[25] This was opposed by certain leading party members and a week later; the Declaration of the Forty-Six was issued, which condemned Stalin's centralisation policies.[26] The declaration stated that the Politburo, Orgburo and the Secretariat was taking complete control over the party, and it was these bodies which elected the delegates to the Party Congresses – in effect making the executive branch, the Party Congress, a tool of the Soviet leadership.[26] On this issue, Trotsky said, "as this regime becomes consolidated all affairs are concentrated in the hands of a small group, sometimes only of a secretary who appoints, removes, gives the instructions, inflicts the penalties, etc."[26] In many ways Trotsky's argument was valid, but he was overlooking the changes, which were taking place.[27] Under Lenin the party ruled through the government, for instance, the only political office held by Lenin was chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, but following Lenin's health the party took control of government activities.[27] The system before Lenin was forced to leave was similar to that of parliamentary systems where the party cabinet, and not the party leadership, were the actual leaders of the country.[27]

It was the power of the center which disturbed Trotsky and his followers. If the Soviet leadership had the power to appoint regional officials, they had the indirect power to elect the delegates of the Party Congresses.[28] Trotsky accused the delegates of the 12th Party Congress (17–25 April 1923) of being indirectly elected by the center, citing that 55.1% of the voting delegates at the congress were full-time members, at the previous congress only 24.8% of the voting-delegates were full-members.[28] He had cause for alarm, because as Anastas Mikoyan noted in his memoirs, Stalin strived to prevent as many pro-Trotsky officials as possible being elected as congress delegates.[28] Trotsky's views went unheeded until 1923, when the Politburo announced a resolution where it reaffirmed party democracy, and even declared the possibility of ending the appointment powers of the center.[29] This was not enough for Trotsky, and he wrote an article in Pravda where he condemned the Soviet leadership and the powers of the center.[29] Zinoviev, Stalin and other members of the Soviet leadership then accused him of factionalism.[30] Trotsky was not elected as a delegate to the 13th Party Congress (23–31 May 1924).[30]

.jpg.webp)

Following the 13th Congress, another power struggle with a different focus began; this time socio-economic policies were the prime motivators for the struggle.[30] Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev supported rapid industrialisation and a planned economy, while Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky supported keeping the NEP.[31] Stalin, in contrast to the others, has often been viewed as standing alone; as Jerry F. Hough explained, he has often been viewed as "a cynical Machiavellian interested only in power."[31]

None of the leading figures of that era were rigid in economic policy, and all of them had supported the NEP previously.[32] With the good harvests in 1922, several problems arose, especially the role of heavy industry and inflation. While agriculture had recovered substantially, the heavy industrial sector was still in recession, and had barely recovered from the pre-war levels.[32] The State Planning Commission (Gosplan) supported giving subsidies to heavy industries, while the People's Commissariat for Finance opposed this, citing major inflation as their reason.[32] Trotsky was the only one in the Politburo who supported Gosplan in its feud with the Commissariat for Finance.[32]

In 1925, Stalin began moving against Zinoviev and Kamenev.[33] The appointment of Rykov as chairman of the Council of People's Commissars was a de facto demotion of Kamenev.[33] Kamenev was acting chairman of the Council of People's Commissars in Lenin's absence.[33] To make matters worse, Stalin began espousing his policy of socialism in one country – a policy often viewed, wrongly, as an attack on Trotsky, when it was really aimed at Zinoviev.[33] Zinoviev, from his position as chairman of the executive committee of the Communist International (Comintern), opposed Stalin's policy.[33] Zinoviev began attacking Stalin within a matter of months, while Trotsky began attacking Stalin for this stance in 1926.[33] At the 14th Party Congress (18–31 December 1925) Kamenev and Zinoviev were forced into the same position that Trotsky had been forced into previously; they proclaimed that the center was usurping power from the regional branches, and that Stalin was a danger to inner-party democracy.[34] The Congress became divided between two factions, between the one supporting Stalin, and those who supported Kamenev and Zinoviev.[34] The Leningrad delegation, which supported Zinoviev, shouted "Long live the Central Committee of our party".[34] Even so, Kamenev and Zinoviev were crushed at the congress, and 559 voted in favour of the Soviet leadership and only 65 against.[34] The newly elected Central Committee demoted Kamenev to a non-voting member of the Politburo.[34] In April 1926 Zinoviev was removed from the Politburo and in December, Trotsky lost his membership too.[34] All of them retained their seats in the Central Committee until October 1927.[35] At the 15th Party Congress (2–19 December 1927) the Left Opposition was crushed; none of its members were elected to the Central Committee.[35] From then on Stalin was the undisputed leader of the Soviet Union, and other leading officials, such as Bukharin, Tomsky, and Rykov were considerably weakened.[36] The Central Committee which was elected at the 16th Party Congress (26 June – 13 July 1930) removed Tomsky and Rykov.[36] Rykov also lost the Council of People's Commissars chairmanship, from the Politburo.[36]

Interwar and war period: 1930–1945

From 1934 to 1953, three congresses were held (a breach of the party rule which stated that a congress must be convened every third year), one conference and 23 Central Committee meetings.[37] This is in deep contrast to the Lenin era (1917–1924), when six Congresses were held, five conferences and 69 meetings of the Central Committee.[37] The Politburo did not convene once between 1950, when Nikolai Voznesensky was killed, and 1953.[37] In 1952, at the 19th Party Congress (5–14 October 1952) the Politburo was abolished and replaced by the Presidium.[37]

In 1930 the Central Committee departments were reorganised, because the Secretariat had lost control over the economy, because of the First Five-Year Plan, and needed more party personnel to supervise the economy.[38] Prior to 1930, Central Committee departments focused on major components of "political work".[38] During Stalin's rule they were specialised.[38] The departments supervised local party officials and ministerial branches within their particular sphere.[38] Four years later, in 1934, new Central Committee departments were established which were independent from the Department for Personnel.[38] Stalin's emphasis on the importance of political and economic work led to another wave of reorganisation of the Central Committee departments in the late-1930s and 1940s.[39] At the 18th Party Congress (10–21 March 1939) the department specializing in industry was abolished and replaced by a division focusing on personnel management, ideology and verification fulfillment.[39] At the 18th Party Conference (15–20 February 1941) it was concluded that the abolition of the Central Committee Department on Industry had led to the neglect of industry.[40] Because of this, specialised secretaries became responsible for industry and transport from the center down to the city level.[40]

The 17th Party Congress (26 January – 10 February 1934) has gone down in history as the Congress of Victors, because of the success of the First-Five Year Plan.[41] During it several delegates formed an anti-Stalin bloc.[41] Several delegates discussed the possibility of either removing or reducing Stalin's powers.[41] Not all conflicts were below the surface, and Grigory Ordzhonikidze, the People's Commissar for Heavy Industry openly disputed with Vyacheslav Molotov, the chairman of the Council of the People's Commissars, about the rate of economic growth.[41] The dispute between Ordzhonikidze and Molotov, who represented the Soviet leadership, was settled by the establishment of a Congress Commission, which consisted of Stalin, Molotov, Ordzhonikidze, other Politburo members and certain economic experts.[42] They eventually reached an agreement, and the planned target for economic growth in the Second Five-Year Plan was reduced from 19% to 16.5%.[42]

The tone of the 17th Party Congress was different from its predecessors; several old oppositionists became delegates, and were re-elected to the Central Committee.[43] For instance, Bukharin, Zinoviev, Yevgeni Preobrazhensky and Georgy Pyatakov were all rehabilitated.[43] All of them spoke at the congress, even if most of them were interrupted.[43] The Congress was split between two dominant factions, radicals (mostly Stalinists) and moderates.[43] Several groups were established before the congress, which either opposed the Stalinist leadership (the Ryutin Group) or opposed socio-economic policies of the Stalinist leadership (the Syrtsov–Lominadze Group, Eismont–Tolmachev Group and the group headed by Alexander Petrovich Smirnov amongst others).[44] Politicians, who had previously opposed the Stalinist leadership, could be rehabilitated if they renounced their former beliefs and began supporting Stalin's rule.[44] However, the leadership was not opening up; Kamenev and Zinoviev were arrested in 1932 (or in the beginning of 1933), and set free in 1934, and then rearrested in 1935, accused of being part of an assassination plot which killed Sergei Kirov.[44]

The majority of the Central Committee members elected at the 17th Party Congress were killed during, or shortly after, the Great Purge when Nikolai Yezhov and Lavrentiy Beria headed the NKVD.[45] Grigory Kaminsky, at a Central Committee meeting, spoke against the Great Purge, and shortly after was arrested and killed.[46] In short, during the Great Purge, the Central Committee was liquidated.[47] Stalin managed to liquidate the Central Committee with the committee's own consent, as Molotov once put it "This gradually occurred. Seventy expelled 10–15 persons, then 60 expelled 15 ... In essence this led to a situation where a minority of this majority remained within the Central Committee ... Such was the gradual but rather rapid process of clearing the way."[48] Several members were expelled from the Central Committee through voting.[47] Of the 139 members elected to the Central Committee at the 17th Congress, 98 people were killed in the period 1936–40.[49] In this period the Central Committee decreased in size; a 78 percent decrease.[49] By the 18th Congress there were only 31 members of the Central Committee, and of these only two were reelected.[50]

Many of the victims of the Moscow Trials were not rehabilitated until 1988.[51] Under Khrushchev, an investigation into the matter concluded that the Central Committee had lost its ruling function under Stalin; from 1929 onwards all decisions in the Central Committee were taken unanimously.[52] In other words, the Central Committee was too weak to protect itself from Stalin and his hangmen.[52] Stalin had managed to turn Lenin's hierarchical model on its head; under Lenin the Party Congress and the Central Committee were the highest decision-making organs, under Stalin the Politburo, Secretariat and the Orgburo became the most important decision-making bodies.[52]

From Stalin to Khrushchev's fall: 1945–1964

In the post-World War II period, Stalin ruled the Soviet Union through the post of chairman of the Council of Ministers.[40] The powers of the Secretariat decreased during this period, and only one member of the Secretariat, Nikita Khrushchev, was a member of the Presidium (the Politburo).[40] The frequency of Central Committee meetings decreased sharply under Stalin, but increased again following his death.[53] After Khrushchev's consolidation of power, the number of Central Committee meetings decreased yet again, but it increased during his later rule, and together with the Politburo, the Central Committee voted to remove Khrushchev as First Secretary in 1964.[53]

When Stalin died on 5 March 1953, Georgy Malenkov, a deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers succeeded him as chairman and as the de facto leading figure of the Presidium (the renamed Politburo). A power struggle between Malenkov and Khrushchev began, and on 14 March Malenkov was forced to resign from the Secretariat.[54] The official explanation for his resignation was "to grant the request of chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers G. M. Malenkov to be released from the duties of the Party Central Committee".[55] Malenkov's resignation made Khrushchev the senior member within the Secretariat, and made him powerful enough to set the agenda of the Presidium meetings alongside Malenkov.[55] Khrushchev was able to consolidate his powers within the party machine after Malenkov's resignation, but Malenkov remained the de facto leading figure of the Party.[56] Together with Malenkov's and Khrushchev's accession of power, another figure, Lavrentiy Beria was also contending for power.[55] The three formed a short-lived Troika,[55] which lasted until Khrushchev and Malenkov betrayed Beria.[57] Beria, an ethnic Georgian, was the Presidium member for internal security affairs, and he was a strong supporter for minority rights and even supported reuniting East and West Germany to establish a strong, and neutral Germany between the capitalist and socialist nations.[57] It was Beria, through an official pronouncement by the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) and not by the Central Committee or the Council of Ministers, who renounced the Doctor's Plot as a fraud.[58]

Beria was no easy man to defeat, and his ethnicisation policies (that a local or republican leaders had to have ethnic origins, and speak the language of the given area) proved to be a tool to strengthen the MVD's grip on local party organs.[59] Khrushchev and Malenkov, who had begun receiving information which stated that the MVD had begun spying on party officials, started to act in the spring of 1953.[59] Beria was defeated at the next Presidium plenums by a majority against him, and not long after, Khrushchev and Malenkov started to plan Beria's fall from power.[60] However, this was no easy task, as Beria was able to inspire fear in his colleagues.[60] In Khrushchev's and Malenkov's first discussion with Kliment Voroshilov, Voroshilov did not want anything to do with it, because he feared "Beria's ears".[60] However, Khrushchev and Malenkov were able to gather enough support for Beria's ouster, but only when a rumour of a potential coup led by Beria began to take hold within the party leadership.[60] Afraid of the power Beria held, Khrushchev and Malenkov were prepared for a potential civil war.[61] This did not happen, and Beria was forced to resign from all his party posts on 26 June, and was later executed on 23 December.[61] Beria's fall also led to criticism of Stalin; the party leadership accused Beria of using Stalin, a sick and old man, to force his own will on the Soviet Union during Stalin's last days.[62] This criticism, and much more, led party and state newspapers to launch more general criticism of Stalin and the Stalin era.[63] A party history pamphlet went so far as to state that the party needed to eliminate "the incorrect, un-Marxist interpretation of the role of the individual in history, which is expressed in propaganda by the idealist theory of the cult of personality, which is alien to Marxism".[62]

Beria's downfall led to the collapse of his "empire"; the powers of the MVD was curtailed, and the KGB was established.[62] Malenkov, while losing his secretaryship, was still chairman of the Council of Ministers, and remained so until 1955.[56] He initiated a policy of strengthening the central ministries, while at the same time ensuing populist policies, one example being to establish a savings of 20.2 billion rubles for Soviet taxpayers.[64] In contrast, Khrushchev tried to strengthen the central party apparatus by focusing on the Central Committee.[64] The Central Committee had not played a notable role in Soviet politics since Nikolai Bukharin's downfall in 1929.[64] Stalin weakened the powers of the Central Committee by a mixture of repression and organisational restructuring.[64] Khrushchev also called for the Party's role to supervise local organs, economic endeavors and central government activities.[64] In September 1953, the Central Committee bestowed Khrushchev with the title of First Secretary, which made his seniority in the Central Committee official.[65] With new acquired powers, Khrushchev was able to appoint associates to the leadership in Georgia, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, Armenia and Moldavia (modern Moldova), while Malenkov, in contrast, was able to appoint an associate to leadership only in Moscow.[65] Under Khrushchev the local party leadership in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR) witnessed the largest turnover in provincial leaders since the Great Purge; two out of three provincial leaders were replaced in 1953 alone.[65] Malenkov was assured an identical policy in government institutions; the most notable change being the appointment of Mikhail Pervukhin, Ivan Tevosian and Maksim Saburov to the Deputy Chairmanship of the Council of Ministers.[65]

During the height of the Malenkov–Khrushchev struggle, Khrushchev actively fought for improvements in Soviet agriculture and the strengthening of the role of the Central Committee.[66] Khrushchev tried to revitalise the Central Committee by hosting several discussions on agriculture at the Central Committee plenums.[66] While no other Presidium members were enthusiastic for such an approach, Khrushchev held several Central Committee meetings from February to March 1954 to discuss agriculture alone.[66] By doing this, Khrushchev was acknowledging a long forgotten fact; the Presidium, the Secretariat and he himself were responsible to the Central Committee.[66] Khrushchev could have gone the other way, since some people were already calling for decreasing the Central Committee's role to "cadres and propaganda alone".[66] A further change was democratisation at the top of the party hierarchy, as Voroshilov noted at a Presidium meeting in 1954.[67] By August 1954 Malenkov's role as de facto head of government was over; Nikolai Bulganin began signing Council of Ministers decrees (a right beholden to the chairman) and the Presidium gave in to Khrushchev's wishes to replace Malenkov.[68] Malenkov was called of revisionism because of his wishes to prioritise light industry over heavy industry.[69] At the same time, Malenkov was accused of being involved in the Leningrad Affair which led to the deaths of innocent party officials.[69] At the Central Committee plenum of 25 January 1955, Khrushchev accused Malenkov of ideological deviations at the same level as former, anti-Stalinist Bukharin and Alexey Rykov of the 1920s.[69] Malenkov spoke twice to the plenum, but it failed to alter his position, and on 8 March 1955 he was forced to resign from his post as chairman of the Council of Ministers; he was succeeded by Nikolai Bulganin, a protege of Khrushchev dating back to the 1930s.[69] Malenkov still remained a powerful figure, and he retained his seat in the Presidium.[69]

The anti-Khrushchev minority in the Presidium was augmented by those opposed to Khrushchev's proposals to decentralize authority over industry, which struck at the heart of Malenkov's power base.[70] During the first half of 1957, Malenkov, Vyacheslav Molotov, and Lazar Kaganovich worked to quietly build support to dismiss Khrushchev.[70] At an 18 June Presidium meeting at which two Khrushchev supporters were absent, the plotters moved that Bulganin, who had joined the scheme, take the chair, and proposed other moves which would effectively demote Khrushchev and put themselves in control.[70] Khrushchev objected on the grounds that not all Presidium members had been notified, an objection which would have been quickly dismissed had Khrushchev not held firm control over the military.[70] As word leaked of the power struggle, members of the Central Committee, which Khrushchev controlled, streamed to Moscow, many flown there aboard military planes, and demanded to be admitted to the meeting.[70] While they were not admitted, there were soon enough Central Committee members in Moscow to call an emergency Party Congress, which effectively forced the leadership to allow a Central Committee plenum.[70] At that meeting, the three main conspirators were dubbed the Anti-Party Group, accused of factionalism and complicity in Stalin's crimes.[70] The three were expelled from the Central Committee and Presidium, as was former Foreign Minister and Khrushchev client Dmitri Shepilov who joined them in the plot.[70] Molotov was sent as Ambassador to Mongolian People's Republic; the others were sent to head industrial facilities and institutes far from Moscow.[70]

At the 20th Party Congress Khrushchev, in his speech "On the Personality Cult and its Consequences", stated that Stalin, the Stalinist cult of personality and Stalinist repression had deformed true Leninist legality.[71] The party became synonymous with a person, not the people – the true nature of the party had become deformed under Stalin, and needed to be revitalised.[71] These points, and more, were used against him, when Khrushchev was forced to resign from all his posts in 1964.[71] Khrushchev had begun to initiate nepotistic policies, initiated policies without the consent of either the Presidium or the Central Committee, a cult of personality had developed and, in general, Khrushchev had developed several characteristics which he himself criticised Stalin of having at the 20th Party Congress.[72] At the 21st Party Congress Khrushchev boldly declared that Leninist legality had been reestablished, when in reality, he himself was beginning to following some of the same policies, albeit not at the same level, as Stalin had.[72]} On 14 October 1964 the Central Committee, alongside the Presidium, made it clear that Khrushchev himself did not fit the model of a "Leninist leader", and he was forced to resign from all his post, and was succeeded by Leonid Brezhnev as First Secretary and Alexei Kosygin as chairman of the Council of Ministers.[72]

Brezhnev era: 1964–1982

Before initiating the palace coup against Khrushchev, Brezhnev had talked to several Central Committee members, and had a list which contained all of the Central Committee members who supported ousting Khrushchev.[73] Brezhnev phoned Khrushchev, and asked him to meet him in Moscow.[73] There, a convened Central Committee voted Khrushchev out of office, both as first secretary of the Central Committee and chairman of the Council of Ministers.[73] At the beginning, Brezhnev's principal rival was Nikolai Podgorny, a member of the Secretariat.[74] Podgorny was later "promoted" to the Chairmanship of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, and Andrei Kirilenko replaced him as secretary in charge of personnel policy.[74] At the same time, Alexander Shelepin, another rival, was replaced as chairman of the Party-State Control Commission and lost his post as deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers. Shelepin was given a further blow when he was removed from the Secretariat.[74]

The number of Central Committee meetings rose again during Brezhnev's early tenure as elected First Secretary,[53] but the number of meetings and their duration steadily decreased during Brezhnev's rule.[75] Before Stalin's consolidation of power, the Central Committee featured open debate, where even leading officials could be criticised.[76] This did not occur during the Brezhnev era, and Politburo officials rarely participated in its meetings; from 1966 to 1976, Alexei Kosygin, Podgorny and Mikhail Suslov attended a Central Committee meeting once; it was in 1973 to ratify the Soviet Union's treaty with West Germany.[76] No Politburo or Secretariat members during the Brezhnev era were speakers during Central Committee meetings.[76] The speaker at the Central Committee meeting which elected the Council of Ministers (the Government) and the Politburo was never listed during the Brezhnev era.[76] Because the average duration of a Central Committee meeting decreased, and fewer meetings were held, many Central Committee members were unable to speak.[77] Some members consulted the leadership beforehand, to ask to speak during meetings.[77] During the May 1966 Central Committee plenum, Brezhnev openly complained that only one member had asked him personally to be allowed to speak.[77] The majority of speakers at Central Committee plenums were high-standing officials.[77]

By 1971, Brezhnev had succeeded in becoming first amongst equals in the Politburo and the Central Committee.[78] Six years later, Brezhnev had succeeded in filling the majority of the Central Committee with Brezhnevites.[78] But as Peter M.E. Volten noted, "the relationship between the general secretary and the central committee remained mutually vulnerable and mutually dependent."[78] The collective leadership of the Brezhnev era emphasised the stability of cadres in the party.[78] Because of this, the survival ratio of full members of the Central Committee increased gradually during the era.[78] At the 23rd Congress (29 March – 8 April 1966) the survival ratio was 79.4 percent, it decreased to 76.5 percent at the 24th Congress (30 March – 9 April 1971), increased to 83.4 percent at the 25th Congress (24 February – 5 March 1976) and at its peak, at the 26th Congress (23 February – 3 March 1981), it reached 89 percent.[78] Because the size of the Central Committee expanded, the majority of members were either in their first or second term.[79] It expanded to 195 in 1966, 141 in 1971, 287 in 1976 and 319 in 1981; of these, new membership consisted of 37, 30 and 28 percent respectively.[79]

Andropov–Chernenko interregnum: 1982–1985

Andropov was elected the party's General Secretary on 12 November 1982 by a decision of the Central Committee.[80] The Central Committee meeting was held less than 24 hours after the announcement of Brezhnev's death.[80] A.R. Judson Mitchell claims that the Central Committee meeting which elected Andropov as General Secretary, was little more than a rubber stamp meeting.[80] Andropov was in a good position to take over the control of the party apparatus; three big system hierarchs, Brezhnev, Kosygin and Suslov had all died.[81] A fourth, Kirilenko, was forced into retirement.[81] At the Central Committee meeting of 22 November 1982, Kirilenko lost his membership in the Politburo (after a decision within the Politburo itself), and Nikolai Ryzhkov, the deputy chairman of the State Planning Committee, was elected to the Secretariat.[82] Ryzhkov became the Head of the Economic Department of the Central Committee, and became the leading Central Committee member on matters regarding economic planning.[82] Shortly afterwards, Ryzhkov, after replacing Vladimir Dolgikh, began to oversee the civilian economy.[82] At the 14–15 June 1983 Central Committee meeting, Vitaly Vorotnikov was elected as a candidate member of the Politburo, Grigory Romanov was elected to the Secretariat and five members of the Central Committee were given full membership.[83] The election of Romanov in the Secretariat, weakened Chernenko's control considerably.[83] Later, Yegor Ligachev was appointed as Head of the Party Organisational Work Department of the Central Committee.[84] Certain Brezhnev appointees were kept, such as Viktor Chebrikov and Nikolai Savinkin. With these appointments, Andropov effectively wielded the powers of the nomenklatura.[85] Even so, by the time he had succeeded in dominating the Central Committee, Andropov fell ill. He was unable to attend the annual parade celebrating the victory of the October Revolution.[86] Chernenko, the official second-ranking secretary, competed for power with Mikhail Gorbachev.[86] The meetings of the Central Committee and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union were postponed to the last possible moment because of Andropov's health.[86] Changes continued however, and the Andropov appointees continued Andropov's course of introducing new blood into the Central Committee and Party apparatus.[86] Vorotnikov and Mikhail Solomentsev were given full membership in the Politburo, Chebrikov was elected a candidate member of the Politburo and Ligachev became a member of the Secretariat.[86] Chernenko's position began to look precarious; Gorbachev was getting stronger by the day.[86] Four days after Andropov's death, on 9 February 1984, Chernenko was elected as the party's General Secretary.[87]

Chernenko was elected as a compromise candidate by the Politburo; the Central Committee could never have accepted another candidate, considering that the majority of the Central Committee members were old Brezhnev appointees.[88] The Politburo could not, despite its powers, elect a General Secretary not supported by the Central Committee. Even so, several leading Politburo members supported Chernenko, such as Nikolai Tikhonov and Viktor Grishin.[88] To make matters worse for Chernenko, he did not have control over the Politburo; both Andrei Gromyko and Dmitriy Ustinov were both very independent politically, and the Politburo still contained several leading Andropov protégés, such as Gorbachev, Vorotnikov, Solomontsev and Heydar Aliyev.[88] Chernenko never got complete control over the Central Committee and Party apparatus; while Andropov never succeeded in removing the majority of Brezhnev appointees in the Central Committee, he had succeeding in dividing the Central Committee along factional lines.[89] In this confusion, Chernenko was never able to become a strong leader.[89] For example, Gorbachev quickly became the party's de facto Second Secretary, even though Chernenko did not support him.[89] The distribution of power within the Central Committee turned Chernenko into little more than a figurehead.[90] In contrast to previous general secretaries, Chernenko did not control the Cadre Department of the Central Committee, making Chernenko's position considerably weaker.[91] However, Chernenko did strengthen his position considerably at the beginning of 1985, not long before his death.[92] Chernenko died on 10 March 1985, and the Central Committee appointed Gorbachev General Secretary on 11 March.[93]

Gorbachev era: 1985–1991

Gorbachev's election as General Secretary was the quickest in Soviet history.[94] The Politburo recommended Gorbachev to the Central Committee, and the Central Committee approved him.[94] The Politburo meeting, which elected Gorbachev to the General Secretaryship, did not include such members as Dinmukhamed Konayev, Volodymyr Shcherbytsky and Vitaly Vorotnikov.[95] Of these three, Konayev and Shcherbytsky were Brezhnevites, and Vorotnikov, while not supporting Gorbachev, took it for granted that Gorbachev would succeed Chernenko.[95] It is conceivable, according to historian Archie Brown, that Konayev and Shcherbytsky would rather have voted in favour of Viktor Grishin as General Secretary, than Gorbachev.[95] At the same meeting, Grishin was asked to chair the commission responsible for Chernenko's funeral; Grishin turned down the offer, claiming that Gorbachev was closer to Chernenko than he was.[95] By doing this, he practically signaled his support for Gorbachev's accession to the General Secretaryship.[95] Andrei Gromyko, the longtime foreign minister, proposed Gorbachev as a candidate for the General Secretaryship.[96] The Politburo and the Central Committee elected Gorbachev as General Secretary unanimously.[97] Ryzhkov, in retrospect, claimed that the Soviet system had "created, nursed and formed" Gorbachev, but that "long ago Gorbachev had internally rebelled against the native System."[97] In the same vein, Gorbachev's adviser Andrey Grachev, noted that he was a "genetic error of the system."[97]

%252C_hammer_and_sickle_and_laurel_branch).jpg.webp)

Gorbachev's policy of glasnost (literally openness) meant the gradual democratisation of the party.[98] Because of this, the role of the Central Committee was strengthened.[98] Several old apparatchiks lost their seats to more open-minded officials during the Gorbachev era.[99] The plan was to make the Central Committee an organ where discussion took place; and in this Gorbachev succeeded.[99]

By 1988, several people demanded reform within the Communist Party itself.[100] At the 19th Conference, the first party conference held since 1941, several delegates asked for the introduction of term limits, and an end to appointments of officials, and to introduce multi-candidate elections within the party.[100] Some called for a maximum of two term-periods in each party body, including the Central Committee, others supported Nikita Khrushchev's policy of compulsory turnover rules, which had been ended by the Brezhnev leadership.[100] Other people called for the General Secretary to either be elected by the people, or a "kind of party referendum".[100] There was also talk about introducing age limits, and decentralising, and weakening the party's bureaucracy.[100] The nomenklatura system came under attack; several delegates asked why the leading party members had rights to a better life, at least materially, and why the leadership was more-or-less untouchable, as they had been under Leonid Brezhnev, even if their incompetence was clear to everyone.[101] Other complained that the Soviet working class was given too large a role in party organisation; scientific personnel and other white-collar employees were legally discriminated against.[101]

Duties and responsibilities

The Central Committee was a collective organ elected at the annual party congress.[102] It was mandated to meet at least twice a year to act as the party's supreme organ.[102] Over the years, membership in the Central Committee increased; in 1934 there were 71 full members, in 1976 there were 287 full members.[103] Central Committee members were elected to the seats because of the offices they held, not their personal merit.[104] Because of this, the Central Committee was commonly considered an indicator for Sovietologists to study the strength of the different institutions.[104] The Politburo was elected by and reported to the Central Committee.[105] Besides the Politburo the Central Committee also elected the Secretariat and the General Secretary, the de facto leader of the Soviet Union.[105] In 1919–1952 the Orgburo was also elected in the same manner as the Politburo and the Secretariat by the plenums of the Central Committee.[105] In between Central Committee plenums, the Politburo and the Secretariat was legally empowered to make decisions on its behalf.[105] The Central Committee (or the Politburo and/or Secretariat in its behalf) could issue nationwide decisions; decisions on behalf of the party were transmitted from the top to the bottom.[106]

Under Lenin the Central Committee functioned like the Politburo did during the post-Stalin era, as the party's leading collective organ.[107] However, as the membership in the Central Committee steadily increased, its role was eclipsed by the Politburo.[107] Between congresses the Central Committee functioned as the Soviet leadership's source for legitimacy.[107] The decline in the Central Committee's standing began in the 1920s, and it was reduced to a compliant body of the Party leadership during the Great Purge.[107] According to party rules, the Central Committee was to convene at least twice a year to discuss political matters (but not matters relating to military policy).[98]

Elections

Delegates at the Party Congresses elected the members of the Central Committee.[108] Nevertheless, there were no competitions for the seats of the Central Committee. The Soviet leadership decided beforehand who would be elected, or rather appointed, to the Central Committee.[109] In the Brezhnev era, for instance, delegates at Party Congresses lost the power to vote in secret against candidates endorsed by the leadership.[109] For instance, at the congresses in 1962 and 1971 the delegates elected the Central Committee unanimously.[109] According to Robert Vincent Daniels the Central Committee was rather an assembly of representatives than an assembly of individuals.[110] The appointment of members often had "an automatic character"; members were appointed to represent various institutions.[110] While Jerry F. Hough agrees with Daniels analysis, he states that other factors must be included; for example an official with a bad relationship with the General Secretary would not be appointed to the Central Committee.[110]

The view that the Politburo appointed Central Committee members is also controversial, considering the fact that each new Central Committee were, in most cases, filled with supporters of the General Secretary.[110] If the Politburo indeed chose the Central Committee membership, various factions would have arisen.[110] While the Politburo theory states indirectly that the Party Congress is a non-important process, another theory, the circular-flow-of-power theory assumed that the General Secretary was able to build a power base among the party's regional secretaries.[111] These secretaries in turn would elect delegates who supported the General Secretary.[111]

Commissions

At the 19th Conference, the first since 1941, Mikhail Gorbachev called for the establishment of Commissions of the Central Committee to allow Central Committee members more leeway in actual policy implementation.[112] On 30 September 1988, a Central Committee Resolution established six Commissions, all of which were led either by Politburo members or Secretaries.[112] The Commission on International Affairs was led by Alexander Yakovlev; Yegor Ligachev led the Commission on Agriculture; Georgy Razumovsky led the Commission on Party Building and Personnel; Vadim Medvedev became head of the Commission on Ideology; the Commission of Socio-economic Questions was led by Nikolay Slyunkov; and Viktor Chebrikov became the head of the Commission on Legal Affairs.[112] The establishment of these commissions was explained in different ways, but Gorbachev later claimed that they were established to end the power struggle between Yakovlev and Ligachev on cultural and ideological matters, without forcing Ligachev out of politics.[112] Ligachev, on the other hand, claimed that the commissions were established to weaken the prestige and power of the Secretariat.[112] The number of meetings held by the Secretariat, following the establishments of the commissions, decreased drastically, before the body was revitalised following the 28th Party Congress (2 July 1990 – 13 July 1990) (see "Secretariat" section).[112]

The commissions did not convene until early 1989, but some commission heads were given responsibilities immediately.[113] For instance, Medvedev was tasked with creating "a new definition of socialism", a task which would prove impossible once Gorbachev became an enthusiastic supporter of some social democratic policies and thinking.[113] Medvedev eventually concluded that the party still upheld Marxism–Leninism, but would have to accept some bourgeois policies.[113]

Central Control Commission

The Party Control Commission (Russian: Комиссия партийного контроля при ЦК КПСС (КПК)) was responsible for, in the words of the Party constitution, "... a) to oversee the implementation of decisions of the Party and the CPSU (b), b) investigate those responsible for violating party discipline, and c) to prosecute violations of party ethics."[114] The 18th Party Congress, held in 1939, recognised that the central task of the Control Commission would be to enhance the control of the Party control.[114] The congress decided that the Control Commission would be, from then on, elected by the Central Committee in the immediate aftermath of the Congress, instead of being elected by the congress itself.[114] Changes were also made to the constitution.[114] It stated that the "Control Commission a) oversaw the implementation of the directives of the CPSU, (b) and the Soviet-economic agencies and party organisations; c) examined the work of local party organisations, d) investigate those responsible for abusing party discipline and the Party constitution".[114]

Departments

The leader of a department was usually given the titles "head" (Russian: zaveduiuschchii),[115] but in practice the Secretariat had a major say in the running of the departments; for example, five of eleven secretaries headed their own departments in 1978.[116] But normally specific secretaries were given supervising duties over one or more departments.[116] Each department established its own cells, which specialised in one or more fields.[117] These cells were called sections. By 1979, there were between 150 and 175 sections, of these only a few were known by name outside the Soviet Union.[117] An example of a department is, for instance, the Land Cultivation section of the Agriculture Department or the Africa section of the International Department.[117] As with the departments, a section was headed by an office named head.[118] The official name for a departmental staff member was instructor (Russian: instruktor).[119]

During the Gorbachev era, a variety of departments made up the Central Committee apparatus.[120] The Party Building and Cadre Work Department assigned party personnel in the nomenklatura system.[120] The State and Legal Department supervised the armed forces, KGB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the trade unions, and the Procuracy.[120] Before 1989 the Central Committee had several departments, but several were abolished in that year.[120] Among these departments there was a Central Committee Department responsible for the economy as a whole, one for machine building, and one for the chemical industry, and so on.[120] The party abolished these departments in an effort to remove itself from the day-to-day management of the economy in favor of government bodies and a greater role for the market, as a part of the perestroika process.[120]

General Secretary

The post of General Secretary was established under the name Technical Secretary in April 1917, and was first held by Elena Stasova.[121] Originally, in its first two incarnations, the office performed mostly secretarial work.[122] The post of Responsible Secretary was then established in 1919 to perform administrative work.[122] The post of General Secretary was established in 1922, and Joseph Stalin was elected its first officeholder.[123] The General Secretary, as a post, was a purely administrative and disciplinary position, whose role was to do no more than determine party membership composition.[123] Stalin used the principles of democratic centralism to transform his office into that of party leader, and later leader of the Soviet Union.[123] In 1934, the 17th Party Congress did not elect a General Secretary and Stalin was an ordinary secretary until his death in 1953, although he remained the de facto leader without diminishing his own authority.[124]

Nikita Khrushchev reestablished the office on 14 September 1953 under the name First Secretary.[125] In 1957 he was nearly removed from office by the Anti-Party Group. Georgy Malenkov, a leading member of the Anti-Party Group, worried that the powers of the First Secretary were virtually unlimited.[125] Khrushchev was removed as leader on 14 October 1964, and replaced by Leonid Brezhnev.[126] At first there was no clear leader of the collective leadership with Brezhnev and Premier Alexei Kosygin ruling as equals.[127] However, by the 1970s Brezhnev's influence exceeded that of Kosygin's and he was able to retain this support by avoiding any radical reforms.[128] The powers and functions of the General Secretary were limited by the collective leadership during Brezhnev's,[128] and later Yuri Andropov's and Konstantin Chernenko's tenures.[129] Mikhail Gorbachev, elected in 1985, ruled the Soviet Union through the office of the General Secretary until 1990, when the Congress of People's Deputies voted to remove Article 6 from the 1977 Soviet Constitution.[130] This meant that the Communist Party lost its position as the "leading and guiding force of the Soviet society" and the powers of the General Secretary were drastically curtailed.[130]

Orgburo

The Organisational Bureau, usually abbreviated Orgburo, was an executive party organ.[131] The Central Committee organised the Orgburo.[131] Under Lenin, the Orgburo met at least 3 times a week, and it was obliged to report to the Central Committee every second week.[131] The Orgburo directed all organisational tasks of the party.[131] In the words of Lenin, "the Orgburo allocates forces, while the Politburo decides policy."[131] In theory, the Orgburo decided all policies relating to administrative and personnel related issues.[131] Decisions reached by the Orgburo would in turn be implemented by the Secretariat.[131] The Secretariat could formulate and decide policies on party administration and personnel if all Orgburo members agreed with the decision.[131] The Politburo frequently meddled in the affairs of the Orgburo, and became active in deciding administrative and personnel policy.[131] Even so, the Orgburo remained an independent organ during Lenin's time, even if the Politburo could veto its resolutions.[131] The Orgburo was an active and dynamic organ, and was in practice responsible for personnel selection for high-level posts; personnel selection for unimportant posts or lower-tier posts were the unofficial responsibility of the Secretariat.[132] However, the Orgburo was gradually eclipsed by the Secretariat.[133] The Orgburo was abolished in 1952 at the 19th Party Congress.[134]

Party education system

The Academy of Social Sciences (Russian: Акаде́мия общественных нау́к, abbreviated ASS) was established on 2 August 1946 (and headquartered in Moscow) as an institution for higher education.[135] It educated future Party and government officials, as well as university professors, scientists and writers.[135] The education was based upon the worldview of the Communist Party and its ideology.[135] It took three years for a student to graduate.[135] Students could earn doctoral degrees in social sciences.[135] The rector of the academy was also the chairman of the academy's Scientific Council.[135] The ASS oversaw the propaganda system alongside the Institute of Marxism–Leninism.[136] By the 1980s, the Academy of Social Sciences was responsible for the activities of the party schools,[137] and became the leading organ in the Soviet education system.[138]

The Higher Party School (Russian: Высшая партийная школа, abbreviated HPS (Russian: ВПШ)) was the organ responsible for teaching cadres in the Soviet Union.[139] It was the successor of the Communist Academy which was established in 1918.[139] The HPS itself was established in 1939 as the Moscow Higher Party School, and it offered its students a two-year training course for becoming a Party official.[140] It was reorganised in 1956 to that it could offer more specialised ideological training.[140] In 1956 the school in Moscow was opened for students from socialist countries.[140] The Moscow Higher Party School was the party school with the highest standing.[140] The school itself had eleven faculties until a Central Committee resolution in 1972 which demanded a shake-up in the curriculum.[141] The first regional (schools outside Moscow) Higher Party School was established in 1946[141] By the early 1950s there existed 70 Higher Party Schools.[141] During the reorganisation drive of 1956, Khrushchev closed-down thirteen of them, reclassified 29 of them as inter-republican and inter-oblast schools.[141]

The HPS carried out the ideological and theoretical training and retraining of the Party and government officials.[139] Courses included the history of the Communist Party, Marxist–Leninist philosophy, scientific communism, political economy of Party-building, the international communist movement, workers and the national liberation movements, the Soviet economy, agricultural economics, public law and Soviet development, journalism and literature, Russian and foreign languages among others.[139] To study at the Higher Party School Party members had to have a higher education.[139] Admission of students was conducted on the recommendation of the Central Committee of the Union republics, territorial and regional committees of the party.[139]

The Institute of Marxism–Leninism (Russian: Институт марксизма-ленинизма, abbreviated IML (Russian: ИМЛ)) was responsible for doctrinal scholarship.[137] Alongside the Academy of Social Sciences, the IML was responsible for overseeing the propaganda system.[136] The IML was established by a merger of the Institute of Marx–Engels (Russian: Институт К. Маркса и Ф. Энгельса) and the Institute of Lenin (Russian: Институт Ленина) in 1931.[142] It was a research institute which collected and preserved the documents of the writings of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Lenin.[142] It published their works, wrote biographies, collected and stored documents on the prominent figures of the party, collected and published the magazine Questions on Party History.[142] It also published monographs and collected documents related to Marxism–Leninism, the history of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Party affairs, scientific communism and history of the international communist movement.[142] A resolution of the Central Committee on 25 June 1968 provided the IML with the right to guide affiliate organisations – the Institute of History of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the union republics, the Leningrad Regional Committee, the Museum of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the Central Museum of Vladimir.[142] Lenin and other affiliate organisastions, the coordination of all research in the field of historical-party science, observation of the publication of scientific papers and works of art and literature about the life and work of the classics of Marxism–Leninism, to provide scientific guidance on the subject of the old Bolsheviks.[142] In 1972 the IML was divided into 9 departments which focused on; the works of Marx and Engels, the works of Lenin, the history of party-building, scientific communism, the history of the international communist movement, coordination branches of research, the Central Party Archive, the Party Library, the Museum of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.[142]

The Institute of Social Sciences (Russian: Институт общественных наук) was established in 1962.[143] Its principal function was to educate foreign Communists from socialist countries and from Third World countries with socialist orientations. The institute came under the jurisdiction of the International Department of the Central Committee under Gorbachev. There was a significant minority within the institute who wished for, or believed in political reform.[144]

Politburo

When Yakov Sverdlov died on 19 March 1919, the party lost its leading organiser.[145] At the 8th Party Congress (18–23 March 1919) the Central Committee was instructed to establish the Political Bureau (Politburo), the Organisational Bureau (Orgburo) and the Secretariat, which was to consist of one Responsible Secretary (later renamed to General Secretary). Originally, the Politburo was composed of 5 (full) members; its first members were Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Joseph Stalin, Lev Kamenev and Nikolay Krestinsky.[145] There were three other (candidate) members; these were Nikolai Bukharin, Mikhail Kalinin and Grigory Zinoviev.[145] At the beginning, the Politburo was charged with solving immediate problems – it became the top-policy organ.[145] Certain delegates of the 8th Party Congress raised objections to the establishment of the Politburo, claiming that its establishment would turn Central Committee members into second-class officials.[145] In response, the Politburo was ordered to deliver reports to the Central Committee, and Central Committee members were given the right to attend Politburo sessions.[145] At the sessions, Central Committee members could participate with a consultative voice, but could not vote on matters.[145]

According to Jerry F. Hough the Politburo in the post-Lenin period, played the role of the Soviet cabinet, and the Central Committee as the parliament to which it was responsible.[146] Under Stalin the Politburo did not meet often as a collective unit, but was still an important body – many of Stalin's closet protégés were members.[147] Membership in the Politburo gradually increased in the era from Lenin until Brezhnev, partly because of Stalin's centralisation of power in the Politburo.[147] The Politburo was renamed in 1952 to the Presidium, and kept that name until 1966.[147] According to Brezhnev, the Politburo met at least once a week, usually on Thursdays.[148] A normal session would last between three and six hours. In between the 24th Party Congress (30 March – 9 April 1971) and the 25th Party Congress (24 February – 5 March 1976), the Politburo convened, at least officially, 215 times.[148] According to Brezhnev, the Politburo decides on "the most important and urgent questions of internal and foreign policy".[148] The Politburo exercised both executive and legislative powers.[149]

Pravda

Pravda (translates to The Truth) was a leading newspaper in the Soviet Union and an organ of the Central Committee.[150] The Organisational Department of the Central Committee was the only organ empowered to relieve Pravda editors from their duties.[151] Pravda was at the beginning a project begun by members of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1905.[152] Leon Trotsky was approached about the possibility of running the new paper because of his previous work in Kyivan Thought, a Ukrainian paper.[152] The first issue was published on 3 October 1908.[152] The paper was originally published in Lvov, but until the publication of the sixth issue in November 1909, the whole operation was moved to Vienna, Austria-Hungary.[152] During the Russian Civil War, sales of Pravda were curtailed by Izvestia, the government run newspaper.[153] At the time, the average reading figure for Pravda was 130,000.[153] This Pravda (the one headquartered in Vienna) published its last issue in 1912, and was succeeded by a new newspaper, also called Pravda, headquartered in St. Petersburg the same year.[154] This newspaper was dominated by the Bolsheviks.[154] The paper's main goal was to promote Marxist–Leninist philosophy and expose the lies of the bourgeoisie.[155] In 1975 the paper reached a circulation of 10.6 million people.[155]

Secretariat

The Secretariat headed the CPSU's central apparatus and was solely responsible for the development and implementation of party policies.[156] It was legally empowered to take over the duties and functions of the Central Committee when it was not in plenum (did not hold a meeting).[156] Many members of the Secretariat concurrently held a seat in the Politburo.[157] According to a Soviet textbook on party procedures, the Secretariat's role was that of "leadership of current work, chiefly in the realm of personnel selection and in the organisation of the verification of fulfillment [of party-state decisions]".[157] "Selections of personnel" (Russian: podbor kadrov) in this instance means the maintenance of general standards and the criteria for selecting various personnel. "Verification of fulfillment" (Russian: proverka ispolneniia) of party and state decisions meant that the Secretariat instructed other bodies.[158]

The Secretariat controlled, or had a major say in, the running of Central Committee departments (see Departments section).[116] The members of the Secretariat, the secretaries, supervised Central Committee departments, or headed them.[116] However, there were exceptions such as Mikhail Suslov and Andrei Kirilenko who supervised other secretaries on top of their individual responsibilities over Soviet policy (foreign relations and ideological affairs in the case of Suslov; personnel selection and the economy in the case of Kirilenko).[116]

While the General Secretary formally headed the Secretariat, his responsibilities not only as the leader of the party but the entire Soviet state left him little opportunity to chair its sessions let alone provide detailed oversight of its work.[159] This led to the creation of a de facto Deputy General Secretary[116] otherwise known as a "Second Secretary" who was responsible for the day-to-day running of the Secretariat.[160]

The powers of the Secretariat were weakened under Mikhail Gorbachev, and the Central Committee Commissions took over the functions of the Secretariat in 1988.[161] Yegor Ligachev, a Secretariat member, noted that these changes completely destroyed the Secretariat's hold on power, and made the body almost superfluous.[161] Because of this, the Secretariat, until 1990, barely met.[161] However, none of these Commissions were as powerful as the Secretariat had been.[161]

The Secretariat was revitalised at the 28th Party Congress (2 July 1990 – 13 July 1990). A newly established office, the Deputy General Secretary, became the official Director of the Secretariat.[162] Gorbachev chaired the first post-Congress session, but after that Vladimir Ivashko, the Deputy General Secretary, chaired its meetings.[162] Though the Secretariat was revitalised, it never regained the authority it held in the pre-Gorbachev days.[162] The Secretariat's authority was strengthened within the limits of the institutions and political rules, which had been introduced under Gorbachev – a return to the old-days was impossible.[162]

Physical location

The Central Committee had its offices on the Staraya Square in Moscow. There were over a dozen buildings in that area, known as the "party town", that the Central Committee controlled. There was a three-story restaurant, buffets, travel bureau, a post office, bookstore, a cinema and a sports center. They employed about 1,500 people in the 1920s, and about 3,000 in 1988.

Legacy

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union is commemorated in several Soviet jokes.

One of such jokes recalled the Prime Minister of Russia Vladimir Putin on 20 April 2011 answering a question of one of parliamentary about introducing own regulatory policies for the Internet,[163][164] who said following using one of the Radio Yerevan jokes,

"Do you know as a joke how there were asking and answering about what the difference is between Tseka (Ce-Ka) and Cheka? Tseka tsks (in Russia it is a sound that requests silence), and Cheka chiks (snips)." Later Putin added, "so, it is that we do not intend to chik anyone".[165][166]

See also

- Bednota – daily newspaper for peasants from March 1918 to January 1931

- Organisation of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Hymn of the Bolshevik Party

Notes

- Russian: Центра́льный комите́т Коммунисти́ческой па́ртии Сове́тского Сою́за – ЦК КПСС, Tsentralniy Komitet Kommunistitcheskoi Partii Sovetskogo Soyuza – TsK KPSS

References

- "Пленум ЦК КПСС 27-28 января 1987 года". ria.ru. MIA "Russia Today". Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Красное Знамя" (PDF). sun.tsu.ru. Body of the Tomsk Regional Committee of the CPSU and the Regional Soviet. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- Maksimenkov, Leonid. "Ivan Denisovich in the Kremlin". kommersant.ru. AO Kommersant. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- Wesson 1978, p. 19.

- Service 2000, pp. 156–158.

- Service 2000, pp. 162, 279, 293, 302–304.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 21.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 25.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 96.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 96–97.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 97.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 97–98.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 98.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 101.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 100–101.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 102.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 102–103.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 103.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 110.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 111.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 111–112.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 112.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 114.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 115.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 121.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 122.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 122–123.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 131.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 132.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 133.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 134.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 135.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 140.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 141.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 142.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 142–143.

- Curtis 1979, p. 44.

- Harris 2005, p. 4.

- Harris 2005, pp. 4–5.

- Harris 2005, p. 5.

- Getty 1987, p. 12.

- Getty 1987, p. 16.

- Getty 1987, p. 17.

- Getty 1987, p. 20.

- Parrish 1996, p. 9.

- Parrish 1996, p. 2.

- Rogovin 2009, p. 174.

- Rogovin 2009, p. 173.

- Rogovin 2009, p. 176.

- Rogovin 2009, pp. 176–177.

- Rogovin 2009, p. 177.

- Rogovin 2009, pp. 178–179.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 459.

- Arnold & Wiener 2012, p. 104.

- Tompson 1997, p. 117.

- Arnold & Wiener 2012, p. 105.

- Tompson 1997, pp. 119–120.

- Tompson 1997, p. 118.

- Tompson 1997, p. 120.

- Tompson 1997, p. 121.

- Tompson 1997, pp. 121–122.

- Tompson 1997, p. 124.

- Tompson 1997, p. 123.

- Tompson 1997, p. 125.

- Tompson 1997, p. 130.

- Tompson 1997, p. 134.

- Tompson 1997, p. 138.

- Tompson 1997, p. 139.

- Tompson 1997, p. 141.

- Tompson 1997, pp. 176–183.

- Thatcher 2011, p. 13.

- Thatcher 2011, p. 14.

- Bacon & Sandle 2002, p. 10.

- Bacon & Sandle 2002, p. 12.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 461.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 462.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 462–463.

- Dowlah & Elliott 1997, p. 147.

- Dowlah & Elliott 1997, p. 148.

- Mitchell 1990, p. 90.

- Mitchell 1990, p. 91.

- Mitchell 1990, p. 92.

- Mitchell 1990, p. 97.

- Mitchell 1990, p. 98.

- Mitchell 1990, p. 99.

- Mitchell 1990, pp. 100–101.

- Mitchell 1990, p. 118.

- Mitchell 1990, pp. 118–119.

- Mitchell 1990, pp. 119–220.

- Mitchell 1990, p. 121.

- Mitchell 1990, p. 122.

- Mitchell 1990, pp. 127–128.

- Mitchell 1990, pp. 130–131.

- Brown 1996, p. 84.

- Brown 1996, p. 85.

- Brown 1996, pp. 86–87.

- Brown 1996, p. 87.

- Sakwa 1998, p. 94.

- Sakwa 1998, p. 96.

- White 1993, p. 39.

- White 1993, pp. 39–40.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 455.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 455–456.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 458.

- Getty 1987, pp. 25–26.

- Getty 1987, p. 27.

- Sakwa 1998, p. 93.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 451.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 452.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 453.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 454.

- Harris 2005, p. 53.

- Harris 2005, p. 54.

- Staff writer. Комиссия партийного контроля [Control Commission]. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). bse.sci-lib.com. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 417–418.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 418.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 420.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 421.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 422.

- "Soviet Union: Secretariat". Library of Congress. May 1989. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- Clements 1997, p. 140.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 126.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, pp. 142–146.

- "Secretariat, Orgburo, Politburo and Presidium of the CC of the CPSU in 1919–1990 – Izvestia of the CC of the CPSU" (in Russian). 7 November 1990. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Ra'anan 2006, p. 69.

- Service 2009, p. 378.

- Brown 2009, p. 403.

- Baylis 1989, pp. 98–99, and 104.

- Baylis 1989, p. 98.

- Kort 2010, p. 394.

- Gill 2002, p. 81.

- Gill 2002, p. 82.

- Gill 2002, p. 83.

- Hosking 1993, p. 315.

- Staff writer. Академия общественных наук при ЦК КПСС [Academy of Social Sciences of the CC of the CPSU]. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). bse.sci-lib.com. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- Remington 1988, p. 91.

- Remington 1988, p. 34.

- Remington 1988, p. 35.

- Staff writer. Высшая партийная школа при ЦК КПСС [Higher Party School of the CC of the CPSU]. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). bse.sci-lib.com. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- Matthews 1983, p. 185.

- Matthews 1983, p. 186.

- Staff writer. Институт марксизма-ленинизма при ЦК КПСС [Institute of Marxism–Leninism of the CC of the CPSU]. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). bse.sci-lib.com. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- Staff writer. ИНСТИТУТ ОБЩЕСТВЕННЫХ НАУК ПРИ ЦК КПСС (ИОН) (1962–1991) [Institute of Social Sciences of the CC of the CPSU] (in Russian). libinfo.org. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- Brown 1996, p. 20.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 125.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 362.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 466.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 471.

- Huskey 1992, p. 72.

- Remington 1988, p. 106.

- Lenoe 2004, p. 202.

- Swain 2006, p. 37.

- Kenez 1985, p. 45.

- Swain 2006, p. 27.

- Staff writer. "Правда" (газета) [Pravda (newspaper)]. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). bse.sci-lib.com. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- Getty 1987, p. 26.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 430.

- Fainsod & Hough 1979, p. 432.

- Hough 1997, p. 84.

- Brown 1989, pp. 180–181.

- Brown 1996, p. 185.

- Harris 2005, p. 121.

- Mikhail Levin. Tseka tsks, and Cheka chiks («ЦК цыкает, а ЧК чикает»). Forbes.ru. 20 April 2011.

- Putin, Nothing is need to be censored in the Internet, while the FSB concerns are valid (Путин: в интернете ничего не надо ограничивать, хотя опасения ФСБ понятны). Gazeta.ru. 20 April 2011

- Vladimir Putin, "Tseka tsks, Cheka chiks" (Владимир Путин: «ЦК – цыкает, ЧК – чикает»). Parlamentskaya Gazeta. 20 April 2011

- Andrei Kolesnikov. Tseka tsks, Cheka chiks. "Putin. "Sterkh" beyond any measure". Litres, 28 November 2017

Bibliography

- Arnold, James; Wiener, Roberta (2012). Cold War: The Essential Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-003-4.

- Baylis, Thomas A. (1989). Governing by Committee: Collegial Leadership in Advanced Societies. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-944-4.

- Brown, Archie (1989). "Power and Policy in a Time of Leadership Transition, 1982-1988". In Brown, Archie (ed.). Political Leadership in the Soviet Union. The Macmillan Press. pp. 163–217. ISBN 978-0-333-41343-2.

- Brown, Archie (1996). The Gorbachev Factor. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-827344-8.

- Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise & Fall of Communism. Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-06-113879-9.