Nikolai Tikhonov

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Tikhonov (Russian: Николай Александрович Тихонов; Ukrainian: Микола Олександрович Тихонов; 14 May [O.S. 1 May] 1905 – 1 June 1997) was a Soviet Russian-Ukrainian statesman during the Cold War. He served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers from 1980 to 1985, and as a First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers, literally First Vice Premier, from 1976 to 1980. Tikhonov was responsible for the cultural and economic administration of the Soviet Union during the late era of stagnation. He was replaced as Chairman of the Council of Ministers in 1985 by Nikolai Ryzhkov. In the same year, he lost his seat in the Politburo; however, he retained his seat in the Central Committee until 1989.

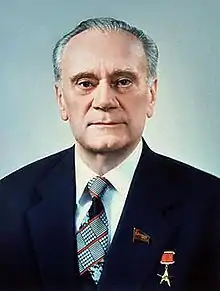

Nikolai Tikhonov Николай Тихонов | |

|---|---|

Tikhonov in 1980 | |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 23 October 1980 – 27 September 1985 | |

| First Deputies | Ivan Arkhipov Heydar Aliyev Andrei Gromyko |

| Preceded by | Alexei Kosygin |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Ryzhkov |

| First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 2 September 1976 – 23 October 1980 | |

| Premier | Alexei Kosygin |

| Preceded by | Dmitry Polyansky |

| Succeeded by | Ivan Arkhipov |

| Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 2 October 1965 – 2 September 1976 | |

| Premier | Alexei Kosygin |

| Deputy Chairman of the State Economic Commission on Current Planning | |

| In office 1963–1965 | |

| Leader | Pyotr Lomako |

| Full member of the 25th, 26th, 27th Politburo | |

| In office 27 November 1979 – 15 October 1985 | |

| Candidate member of the 25th Politburo | |

| In office 27 November 1978 – 27 November 1979 | |

| Full member of the 23rd, 24th, 25th, 26th, 27th Central Committee | |

| In office 1966–1989 | |

| Candidate member of the 22nd Central Committee | |

| In office 1961–1966 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 May 1905 Kharkiv, Kharkov Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 1 June 1997 (aged 92) Moscow, Russia |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow |

| Citizenship | Soviet and Russian |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1940–1989) |

| Alma mater | Dnipropetrovsk Metallurgical Institute |

| Profession | Metallurgist |

He was born in the city of Kharkiv in 1905 to a Russian-Ukrainian working-class family; he graduated in the 1920s and started working in the 1930s. Tikhonov began his political career in local industry, and worked his way up the hierarchy of Soviet industrial ministries. He was appointed deputy chairman of the Gosplan in 1963. After Alexei Kosygin's resignation Tikhonov was voted into office as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. In this position, he refrained from taking effective measures to reform the Soviet economy, a need which was strongly evidenced during the early–mid-1980s. He retired from active politics in 1989 as a pensioner. Tikhonov died on 1 June 1997.

Early life and career

Tikhonov was born in the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv on 14 May [O.S. 1 May] 1905 to a Russian-Ukrainian working-class family; he graduated from the St. Catherine Institute of Communications in 1924. Tikhonov worked as an assistant engineer from 1924 to 1926. Four years later, in 1930, Tikhonov graduated as an engineer, earning a degree from the Dnipropetrovsk Metallurgical Institute. From 1930 to 1941, Tikhonov worked as an engineer at the Lenin Metallurgical Plant in Dnipropetrovsk; he was appointed as the plant's Chief Engineer in January 1941.[1]

It was during his stay in Dnipropetrovsk that he met Leonid Brezhnev, a future leader of the Soviet Union.[2] Tikhonov joined the All-Union Communist Party (bolsheviks) in 1940 and by the end of the decade, had secured a job as a plant director.[3] As a director, Tikhonov was able to show off his organisational skills; under his leadership the plant became the first in the region to reopen a hospital, organising dining rooms and restoring social clubs for workers caught up in the aftermath of the Eastern Front.[1] Tikhonov was quickly promoted, and started working for the Ministry of Ferrous Metallurgy in the 1950s. Between 1955 and 1960 Tikhonov became a Deputy Minister of the Ministry of Ferrous Metallurgy, a member (and later chairman) of the Scientific Council of the Council of Ministers, and finally, a deputy chairman of the State Planning Committee.[4] At the 22nd Party Congress Tikhonov was elected to the Central Committee as a non-voting member.[1] At the 23rd party congress in 1966, Tikhonov was elected a member of the Central Committee.[1] Tikhonov was awarded the Hero of Socialist Labour award for his first time.[3]

During his tenure as Deputy Premier, Tikhonov was in charge of metallurgy and chemical industry; his responsibilities did not change with his ascension to the post of First Deputy Premier. However, he did provide a general coordination for heavy industry.[5] When Alexei Kosygin, the Premier, was on sick leave in 1976 Brezhnev took advantage of his illness by appointing Tikhonov to the office of First Deputy Premier. As First Deputy Premier, Tikhonov was able to reduce Kosygin to a standby figure.[2] Tikhonov was, however, one of the few who got along with both Brezhnev and Kosygin, both of them liked his candor and honesty.[6] In 1978 Tikhonov was elected a candidate member of the Politburo and was made a voting member of the Politburo in 1979.[7] Tikhonov was not informed of the decision to intervene in Afghanistan; the reason being his bad relationship with Dmitriy Ustinov, the Minister of Defense at the time.[6]

Premiership (1980–1985)

Appointment and the 26th Congress

When Alexei Kosygin resigned in 1980, Tikhonov, at the age of 75, was elected the new Chairman of the Council of Ministers.[8] During his five-year term as premier Tikhonov refrained from reforming the Soviet economy, despite all statistics from that time showing the economy was stagnating.[1] Tikhonov presented the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (1981–85) at the 26th Party Congress, and told the delegates that the state would allocate nine million roubles for mothers who were seeking parental leave.[9] In his presentation to the congress, Tikhonov admitted that Soviet agriculture was not producing enough grain. Tikhonov called for an improvement in Soviet–US relations, but dismissed all speculations that the Soviet economy was in any sort of crisis.[10] Despite this, Tikhonov admitted to economic "shortcomings" and acknowledged the ongoing "food problem"; other topics for discussion were the need to save energy resources, boost labour productivity and to improve the quality of Soviet produced goods.[11] Early in his term, in January 1981, Tikhonov admitted that the government's demographic policy was one of the weakest areas of his cabinet.[12] In reality, however, he along with many others, were beginning to worry that not enough Russians were being born. The Era of Stagnation reduced the birth rate, and increased the death rate of the Russian population.[12]

Under Andropov and Chernenko

Leonid Brezhnev awarded Tikhonov the Hero of Socialist Labour, after being advised to do so by Konstantin Chernenko. Upon Brezhnev's death in 1982, Tikhonov supported Chernenko's candidacy for the General Secretaryship. Chernenko lost the vote, and Yuri Andropov became General Secretary.[13] It has been suggested that Andropov had plans of replacing Tikhonov with Heydar Aliyev. Historian William A. Clark noted how Aliyev, a former head of the Azerbaijani KGB, was appointed to the First Deputy Premiership of the Council of Ministers without Tikhonov's consent; however, Andropov's death in 1984 left Tikhonov secure in his office.[14] Some Western analysts speculated that the appointment of Andrei Gromyko to the First Deputy Premiership, again without Tikhonov's consent, was a sign that his position within the Soviet hierarchy was weakened. Tikhonov was on a state visit to Yugoslavia when Gromyko was appointed to the First Deputy Premiership.[15]

With his health failing, Andropov used his spare times to write speeches to the Central Committee. In one of these speeches Andropov told the Central Committee that Mikhail Gorbachev, and not Chernenko, would succeed him upon his death. His speech was not read out to the Central Committee plenum because of an anti-Gorbachev troika consisting of Chernenko, Dmitriy Ustinov and Tikhonov. During Andropov's last days, Tikhonov presided over the Politburo sessions, headed the 1984 Soviet delegation to the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance conference in East Berlin, conducted bilateral relations with the Eastern Bloc states, and hosted the Prime Minister of Finland when he visited the Soviet Union. In short, in-between Andropov's last days and Chernenko's rise to power, Tikhonov was the dominant driving figure of the Soviet Union. However, Tikhonov peacefully stepped away, and supported Chernenko's candidacy for General Secretary.[16] When Chernenko died in 1985, Tikhonov tried, but failed, to find a contender to Gorbachev's candidacy to the General Secretaryship.[17]

Gorbachev and resignation

Upon Gorbachev's ascension to power, Tikhonov was elected chairman of the newly established Commission on Improvements of the Management System. The title of chairman was largely honorary, and its de facto head was its deputy chairman, Nikolai Ryzhkov.[18] On 23 May 1985 Tikhonov presented his development plan for 1985 to 1990, and up until 2000, the plan was criticised by co-workers, and Gorbachev told his colleagues that Tikhonov was "ill-equipped" for the Premiership. Tikhonov forecast estimated growth of 20–22 percent growth in Soviet national income, an increase of 21–24 percent in industrial growth and doubling Soviet agriculture output by 2000.[3] As part of Gorbachev's plan of removing, and replacing, the most conservative members[19] of the Politburo, Tikhonov was compelled to retire.[20] Ryzhkov succeeded Tikhonov in office on 27 September 1985.[20] His resignation was made official at a Central Committee plenum in September 1985.[21] It is noteworthy that by the time of his resignation, Tikhonov was the oldest member of the Soviet leadership.[22] Tikhonov was active in Soviet politics, albeit in a much less prominent role, until 1989 when he lost his seat in the Central Committee.[1]

Later life and death

After his forced resignation from active politics in 1989, Tikhonov wrote a letter to Mikhail Gorbachev which stated that he regretted supporting his election to the General Secretaryship.[3] This view was strengthened when the Communist Party was banned in the Soviet Union. After his retirement, he lived the rest of his life in seclusion at his dacha. As one of his friends noted, he lived as "a hermit" and never showed himself in public[3] and that his later life was very difficult as he had no children and because his wife had died.[3] Prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union Tikhonov worked as a State Advisor to the Supreme Soviet.[23] Tikhonov died on 1 June 1997 and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery.[24] Shortly before his death, he wrote a letter addressed to Yeltsin: "I ask you to bury me at public expense, since I have no financial savings."[25]

As he received a three-room apartment when he was deputy chairman, he lived in it with his wife until his death. They had no children, and they lived very modestly. As a former prime minister, he was left with a dacha, private security, and a personal pension. Tikhonov did not have any savings. When he worked in the government, he and his wife spent all their money on the purchase of buses, which they donated to pioneer camps and schools. After the liquidation of the USSR, the personal pension was canceled, and Tikhonov received a regular old-age pension. And the guys from the security were buying him fruits from their own salaries.[6]

According to Time magazine, Tikhonov was a "tried and tested yes man" who had very little experience in foreign and defence policy when he took over the Premiership from Alexei Kosygin.[26] A bust dedicated to Tikhonov can be found in Kharkiv, his birthplace.[27] Tikhonov, when compared to other Soviet premiers, has made little impact on post-Soviet culture and his legacy is remembered by few today.[6] During his lifetime Tikhonov was awarded several awards; he was awarded the Order of Lenin nine times, the Order of the Red Banner of Labour twice, one Red Star, two Stalin Prizes and several medals and foreign awards.[1]

Decorations and awards

- Hero of Socialist Labour (1975, 1982)

- Nine Orders of Lenin

- Order of the October Revolution

- Two Orders of the Red Banner

- Order of the Red Star

- Stalin Prize;

- 1st class (1943) – a radical improvement of the production of pipes and mortar ammunition

- 3rd class (1951) – for the development and commercial production of seamless pipes of large diameter

- Doctor of Technical Sciences (1961)

References

- Симоновым, A.A. Тихонов, Николай Александрович [Tikhonov, Nikolai Aleksandrovich] (in Russian). warheroes.ru. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- Zemtsov 1989, p. 119.

- Тихонов, Николай Александрович (in Russian). proekt-wms.narod.ru. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- Zemtsov 1989, p. 70.

- Hough, Jerry F.; Fainsod, Merle (1979). How the Soviet Union is Governed. Harvard University Press. p. 382. ISBN 978-0-674-41030-5.

- Охранники скидывались на фрукты бывшему премьеру. Kommersant (in Russian). 9 May 2000. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- Brown, Archie (1997). The Gorbachev factor. Oxford University Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-19-288052-9.

- Ploss, Sidney (2010). The Roots of Perestroika: The Soviet Breakdown in Historical Context. McFarland & Company. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7864-4486-1.

- Lahusen, Thomas; Solomon, Peter H. (2008). What is Soviet now?: identities, legacies, memories. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 206. ISBN 978-3-82580640-8.

- "Tikhonov Bids for U.S. Trade". Reading Eagle. 27 February 1981.

- "Soviets put squeeze on U.S. for summit". Tri-City Herald. 27 February 1981.

- Service, Robert (2009). History of Modern Russia: From Tsarism to the Twenty-first Century. Penguin Books Ltd. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-67403493-8.

- Zemtsov 1989, p. 131.

- Clark, William A. (1993). Crime and punishment in Soviet officialdom: combating corruption in the political elite, 1965–1990. M. E. Sharpe. p. 157. ISBN 1-56324-055-6.

- "Gromyko's promotion may be premier's loss". Deseret News. 25 March 1983.

- Zemtsov 1989, p. 146.

- Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise & Fall of Communism. Bodley Head. pp. 482–83. ISBN 978-1-84595-067-5.

- Gaidar, Yegor (1999). Days of defeat and victory. University of Washington Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-295-97823-6.

- Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise & Fall of Communism. Bodley Head. p. 488. ISBN 978-1-84595-067-5.

- Service, Robert (2009). History of Modern Russia: From Tsarism to the Twenty-first Century. Penguin Books Ltd. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-14-103797-4.

- Haghayeghi, Mehrdad (1996). Islam and Politics in Central Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 46. ISBN 0-312-16488-2.

- Zwass, Adam (1989). The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance: the thorny path from political to economic integration. M. E. Sharpe. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-87332-496-0.

- Биографии. Forbes.ru (in Russian). 24 September 2009. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Тихонов, Николай Александрович (in Russian). warheroes.ru. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- "Министр СССР: о реформах Брежнев говорил — "не дергайте людей, дайте людям отдохнуть"". ТАСС. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- "Soviet Union: And Then There Was One". Time. 3 November 1980. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Тихонов, Николай Александрович (in Russian). warheroes.ru. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

Sources

- Zemtsov, Ilya (1989). Chernenko: The Last Bolshevik: The Soviet Union on the Eve of Perestroika. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88738-260-4.

- Tikhonov's Selected Speeches and Writings