Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone (Spanish: Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the territory of Panama, consisting of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending five miles (8 km) on each side of the centerline, but excluding Panama City and Colón.[1] Its capital was Balboa.

Panama Canal Zone Zona del Canal de Panamá | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1903–1979 | |||||||||

Flag

Seal

| |||||||||

| Motto: The Land Divided, The World United | |||||||||

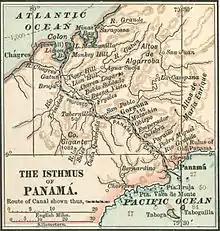

Map of Panama Canal Zone. The Caribbean Sea is at the top left, the Gulf of Panama is at bottom right | |||||||||

| Status | Unincorporated territory of the United States | ||||||||

| Capital | Balboa | ||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish, English | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Zonian | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty | November 18, 1903 | ||||||||

• Torrijos–Carter Treaties | October 1, 1979 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 1,432 km2 (553 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency | United States dollar Panamanian balboa (tolerated) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Panama | ||||||||

The Panama Canal Zone was created on November 18, 1903 from the territory of Panama; established with the signing of the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, which allowed for the construction of the Panama Canal within the territory by the United States. The zone existed until October 1, 1979, when it was incorporated back into Panama.

In 1904, the Isthmian Canal Convention was proclaimed. In it, the Republic of Panama granted to the United States in perpetuity the use, occupation, and control of a zone of land and land underwater for the construction, maintenance, operation, sanitation, and protection of the canal. From 1903 to 1979, the territory was controlled by the United States, which had purchased the land from its private and public owners, built the canal and financed its construction. The Canal Zone was abolished in 1979, as a term of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties two years earlier; the canal itself was later under joint U.S.–Panamanian control until it was fully turned over to Panama in 1999.[2]

History

Proposals for a canal

Proposals for a canal across the Isthmus of Panama date back to 1529, soon after the Spanish conquest. Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón, a lieutenant of conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa, suggested four possible routes, one of which closely tracks the present-day canal. Saavedra believed that such a canal would make it easier for European vessels to reach Asia. Although King Charles I was enthusiastic and ordered preliminary works started, his officials in Panama soon realized that such an undertaking was beyond the capabilities of 16th-century technology. One official wrote to Charles, "I pledge to Your Majesty that there is not a prince in the world with the power to accomplish this".[3] The Spanish instead built a road across the isthmus. The road came to be crucial to Spain's economy, as treasure obtained along the Pacific coast of South America was offloaded at Panama City and hauled through the jungle to the Atlantic port of Nombre de Dios, close to present-day Colón.[4] Although additional canal building proposals were made throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, they came to naught.[3]

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw a number of canals built. The success of the Erie Canal in the United States and the collapse of the Spanish Empire in Latin America led to a surge of American interest in building an interoceanic canal. Beginning in 1826, US officials began negotiations with Gran Colombia (present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Panama), hoping to gain a concession for the building of a canal. Jealous of their newly obtained independence and fearing that they would be dominated by an American presence, the president Simón Bolívar and New Granadan officials declined American offers. The new nation was politically unstable, and Panama rebelled several times during the 19th century.

In 1836 U.S. statesman Charles Biddle reached an agreement with the New Granadan government to replace the old road with an improved one or a railroad, running from Panama City on the Pacific coast to the Chagres River, where a steamship service would allow passengers and freight to continue to Colón. His agreement was repudiated by the Jackson administration, which wanted rights to build a canal. In 1841, with Panama in rebellion again, British interests secured a right of way over the isthmus from the insurgent regime and occupied Nicaraguan ports that might have served as the Atlantic terminus of a canal.[5][6] In 1846 the new US envoy to Bogotá, Benjamin Bidlack, was surprised when, soon after his arrival, the New Granadans proposed that the United States be the guarantor of the neutrality of the isthmus. The resulting Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty allowed the United States to intervene militarily to ensure that the interoceanic road (and when it was built, the Panama Railroad as well) would not be disrupted. New Granada hoped that other nations would sign similar treaties, but the one with the United States, which was ratified by the US Senate in June 1848 after considerable lobbying by New Granada, was the only one.[7]

The treaty led the U.S. government to contract for steamship service to Panama from ports on both coasts. When the California Gold Rush began in 1848, traffic through Panama greatly increased, and New Granada agreed to allow the Panama Railroad to be constructed by American interests. This first "transcontinental railroad" opened in 1850.[8] There were riots in Panama City in 1856; several Americans were killed. US warships landed Marines, who occupied the railroad station and kept the railroad service from being interrupted by the unrest. The United States demanded compensation from New Granada, including a zone 20 miles (32 km) wide, to be governed by US officials and in which the United States might build any "railway or passageway" it desired. The demand was dropped in the face of resistance by New Granadan officials, who accused the United States of seeking a colony.[9]

Through the remainder of the 19th century, the United States landed troops several times to preserve the railway connection. At the same time, it pursued a canal treaty with Colombia (as New Granada was renamed). One treaty, signed in 1868, was rejected by the Colombian Senate, which hoped for better terms from the incoming Grant administration. Under this treaty, the canal would have been in the middle of a 20-mile zone, under American management but Colombian sovereignty, and the canal would revert to Colombia in 99 years. The Grant administration did little to pursue a treaty and, in 1878, the concession to build the canal fell to a French firm. The French efforts eventually failed, but with Panama apparently unavailable, the United States considered possible canal sites in Mexico and Nicaragua.[10]

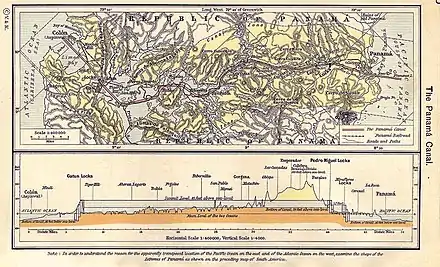

Map of completed canal, 1911

The Spanish–American War of 1898 added new life to the canal debate. During the war, American warships in the Atlantic seeking to reach battle zones in the Pacific had been forced to round Cape Horn. Influential naval pundits, such as Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, urged the construction of a Central American canal. In 1902, with the French efforts moribund, US president Theodore Roosevelt backed the Panama route, and Congress passed legislation authorizing him to purchase the French assets[11] on the condition that an agreement was reached with Colombia.[12] In March 1902 Colombia set its terms for such a treaty: Colombia was to be sovereign over the canal, which would be policed by Colombians paid for by the United States. The host nation would receive a larger percentage of the tolls than provided for in earlier draft treaties. The draft terms were quickly rejected by American officials. Roosevelt was in a hurry to secure the treaty; the Colombians, to whom the French property would revert in 1904, were not. Negotiations dragged on into 1903, during which time there was unrest in Panama City and Colón; the United States sent in Marines to guard the trains. Nevertheless, in early 1903, the United States and Colombia signed a treaty which, despite Colombia's previous objections, gave the United States a 6 miles (9.7 km) wide zone in which it could deploy troops with Colombian consent. On August 12, 1903, the Colombian Senate voted down the treaty 24–0.[13]

Roosevelt was angered by the Colombians' actions, especially when the Colombian Senate made a counteroffer that was more financially advantageous to Colombia. A Frenchman who had worked on his nation's canal efforts, Philippe Bunau-Varilla, represented Panamanian insurgents; he met with Roosevelt and with Secretary of State John Hay, who saw to it that his principals received covert support. When the revolution came in November 1903, the United States intervened to protect the rebels, who succeeded in taking over the province, declaring it independent as the Republic of Panama. Bunau-Varilla was initially the Panamanian representative in the United States, though he was about to be displaced by actual Panamanians, and hastily negotiated a treaty, giving the United States a zone 20 miles (32 km) wide and full authority to pass laws to govern that zone. The Panama Canal Zone (Canal Zone, or Zone) excluded Panama City and Colón, but included four offshore islands, and permitted the United States to add to the zone any additional lands needed to carry on canal operations. The Panamanians were minded to disavow the treaty, but Bunau-Varilla told the new government that if Panama did not agree, the United States would withdraw its protection and make the best terms it could with Colombia. The Panamanians agreed, even adding a provision to the new constitution, at US request, allowing the larger nation to intervene to preserve public order.[14]

Construction (1903–1914)

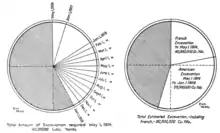

The treaty was approved by the provisional Panamanian government on December 2, 1903, and by the US Senate on February 23, 1904. Under the treaty, Panama received US$10 million, much of which the United States required to be invested in that country, plus annual payments of US$250,000; with those payments made, as well as for the purchase of the French company assets, the Canal Zone was formally turned over by Panama on May 4, 1904, when American officials reopened the Panama City offices of the canal company and raised the American flag.[15] This marked the beginning point for U.S. excavation and construction which concluded in August 1914 with the opening of the canal to commercial traffic.

Governance

By order of President Theodore Roosevelt under the Panama Canal Acts of 1902 and 1904 the secretary of War was made supervisor of canal construction and the second Isthmian Canal Commission made the governing body for the Canal Zone.[16] Under the Panama Canal Act of May 24, 1912, President Woodrow Wilson issued Executive Order 1885, January 27, 1914, effective April 1, 1914, abolishing the previous governance and placing it under the direction of the Secretary of War, with the entity designated as The Panama Canal.[16][17] This Executive Order charged the Governor of the Panama Canal with "completion, maintenance, operation, government and sanitation of the Panama Canal and its adjuncts and the government of the Canal Zone."[17] A number of departments were specified in the order, with others to be established as needed by the Governor of the Panama Canal with approval of the President and under the supervision of the Secretary of War.[17] Defense of the canal was the responsibility of the Secretary of War who retained control of troops with provisions for presidential appointment of an Army officer in wartime who would have "exclusive authority over the operation of the Panama Canal and the Government of the Canal Zone."[17] The executive order noted in closing "that the supervision of the operations of the Panama Canal under the permanent organization should be under the Secretary of War," thus establishing the essentially military arrangement and atmosphere for the canal and Canal Zone.[17]

On September 5, 1939, with the outbreak of war in Europe Executive Order 8232 placed governance of the Canal and "all its adjuncts and appurtenances, including the government of the Canal Zone" under the exclusive control of the Commanding General, Panama Canal Department for the duration.[18][19]

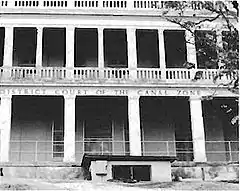

Effective July 1, 1951, under an act of Congress dated September 26, 1950 (64 Stat. 1038), governance of the Canal Zone was through the Canal Zone Government with the canal operated by the Panama Canal Company until 1979 when the Panama Canal Commission took over its governance.[20][21] The entire structure was under the control of the United States government with the secretary of the Army appointing the Panama Canal Company board of directors and the Canal Zone Government was entirely financed by the company.[22] The office of the governor of the Panama Canal Zone was not usually a stepping stone to higher political office but a position given to US Army active duty general officers of the United States Army Corps of Engineers.[23] The governor was also president of the Panama Canal Company. The Canal Zone had its own police force (the Canal Zone Police), courts, and judges (the United States District Court for the Canal Zone). Despite being an unincorporated territory, the Canal Zone was never granted a congressional delegate.

Everyone worked for the company or the government in one form or another. Residents did not own their homes; instead, they rented houses assigned primarily based on seniority in the zone. When an employee moved away, the house would be listed and employees could apply for it. The utility companies were also managed by the company. There were no independent stores; goods were brought in and sold at stores run by the company, such as a commissary, housewares, and so forth.

In 1952 the Panama Canal Company was required to go on a break-even basis in an announcement made in the form of the president's budget submission to the United States Congress.[24] Though company officials had been involved in previewing the requirement, there was no disclosure in advance, even though the Bureau of the Budget directed that the new régime become effective on March 1.[24] The company organization was realigned into three main divisions; Canal Activity and Commercial Activity with the Service Activity providing services to both operating activities at rates sufficient to recover costs.[25] Rate adjustments in housing and other employee services would be required and a form of valuation, compared to a property tax, would be used to determine each division's contribution to the Canal Zone Government.[26]

Territory

Panama Canal Zone was located within the territory of Panama, consisting of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending 5 miles (8.0 km) on each side of the centerline, but excluding Panama City and Colón, which would have otherwise fallen in part within the limits of the Canal Zone. When artificial lakes were created to assure a steady supply of water for the locks, those lakes were included within the zone. Its border spanned two of the provinces of Panama: Colón and Panamá. The total area of the territory was 553 square miles (1,430 km2).[1]

Although it was a United States territory, the zone did not have formal boundary restrictions on Panamanians transiting to either half of their country, or for any other visitors. A Panama Canal fence did exist along the main highway, although it was only a safety measure to separate pedestrians from traffic, and some of the U.S. territories was beyond it. In Panama City, if there were no protests interfering with movement, one could enter the Zone simply by crossing a street.

Tensions and the end of the Canal Zone

In 1903, the United States, having failed to obtain from Colombia the right to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, which was part of that country, sent warships in support of Panamanian independence from Colombia. This being achieved, the new nation of Panama ceded to the Americans the rights they wanted in the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty. Over time, though, the existence of the Canal Zone, a political exclave of the United States that cut Panama geographically in half and had its own courts, police, and civil government, became a cause of conflict between the two countries. Major rioting and clashes occurred on May 21, 1958, and on November 3, 1959. Demonstrations occurred at the opening of the Thatcher Ferry Bridge, now known as the Bridge of the Americas, in 1962 and serious rioting occurred in January 1964. This led to the United States easing its controls in the Zone. For example, Panamanian flags were allowed to be flown alongside American ones. After extensive negotiations, the Canal Zone ceased to exist on October 1, 1979, in compliance with provisions of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties.

In 1989, the United States invaded Panama and virtually all of the military operations took place within the Canal Zone including Operation Acid Gambit, the Raid at Renacer Prison among many others including operations at the entrance, exit and all of the locks.

Lifestyle of residents

"Gold" roll and "silver" roll

During its construction and into the 1940s, the labor force in the Canal Zone (which was almost entirely publicly employed) was divided into a "gold" roll (short for payroll) classification, and a "silver" roll classification. The origins of this system are unclear, but it was the practice on the 19th-century Panama Railroad to pay Americans in US gold and local workers in silver coin.[27] Although some Canal Zone officials compared the gold roll to military officers and the silver roll to enlisted men, the characteristic that determined on which roll an employee was placed was race. With very few exceptions, American and Northern European whites were placed on the gold roll, and blacks and southern European whites on the silver roll. American blacks were generally not hired; black employees were from the Caribbean, often from Barbados and Jamaica. American whites seeking work as laborers, which were almost entirely silver roll positions, were discouraged from applying.[28] In the early days of the system, bosses could promote exceptional workers from silver to gold, but this practice soon ceased as race came to be the determining factor.[29] As a result of the initial policy, there were several hundred skilled blacks and Southern Europeans on the gold roll.[30] In November 1906, Chief Engineer John Stevens ordered that most blacks on the gold roll be placed on the silver roll instead (a few remained in such roles as teachers and postmasters); the following month, the Canal Commission reported that the 3,700 gold roll employees were "almost all white Americans" and the 13,000 silver roll workers were "mostly aliens".[28] On February 8, 1908, President Roosevelt ordered that no further non-Americans be placed on the gold roll. After Panamanians objected, the gold roll was reopened to them in December 1908; however, efforts to remove blacks and non-Americans from the gold roll continued.[31]

Until 1918, when all employees began to be paid in US dollars, gold roll employees were paid in gold, in American currency, while their silver roll counterparts were paid in silver coin, initially Colombian pesos. Through the years of canal construction, silver roll workers were paid with coins from various nations; in several years, coin was imported from the United States because of local shortages. Even after 1918, both the designations and the disparity in privileges lingered.[30]

"Diasporization" in the Panama Canal Zone

Until the end of World War II in 1945, the Panama Canal Zone operated under a Jim Crow society, where the category of "gold" represented white, U.S. workers and the title "silver" represented the non-white, non-U.S. workers on the Zone. There were even separate entrances for each group at the Post Office. After the strike of 1920, the Afro diasporic workers were banned from unionizing by the U.S. Canal officials. As a result, the Panama Canal West Indian Employees Association (PCWIEA) was created in 1924 to fill this vacuum of representation.[32] The PCWIEA did not garner much support on the Canal Zone because of its restrictive membership policies and the haunting of the 1920 strike and its damaging consequences. However, in 1946, the PCWIEA summoned the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) for representation and the establishment of a local union. In July of that year, the West Indian and Panamanian workers received a charter for Local 713 of the United Public Workers of America (UPWA)-CIO.[33][34] Together, with the assistance of U.S. representatives for the Local, these Afro-diasporic workers came together to secure material benefits in their livelihoods. They organized together in order to pose a serious threat to the Jim Crow system which resulted, however, only in minimal gains. American segregationist policies persisted as it related to housing and schooling.[35] In the end, ties to communism destroyed the UPWA and as a result Local 713 collapsed.[36] Nevertheless, Frank Gurridy describes this as diasporization, "diaspora in action, or the ways Afro-diasporic linkages were made in practice".[37] In the case of the Panama Canal Zone, these linkages were made not only by the West Indian and Panamanian communities, but also between the Afro descended workers on the Zone and African Americans, on the mainland of the U.S., through the transnational struggle to dismantle the system of Jim Crow.

Housing and goods

Canal Zone housing was constructed in the early days of construction, as part of Stevens' plans. Housing constructed for couples and families consisted of structures containing four two-story apartments. The units had corrugated-iron roofs, and were uniformly painted gray with white trim. Constructed of pine clapboard, they had long windows and high ceilings, allowing for air movement. Better-paid employees were entitled to more square feet of housing, the unit in which allowances were expressed. Initially, employees received one square foot per dollar of monthly salary. Stevens from the first encouraged gold roll employees to send for their wives and children; to encourage them to do so, wives were granted a housing allowance equal to their husband's, even if they were not employees. Bachelors mostly resided in hotel-like structures. The structures all had screened verandas and up-to-date plumbing. The government furnished power, water, coal for cooking, ice for iceboxes, lawn care, groundskeeping, garbage disposal, and, for bachelors only, maid service.[38]

In the first days of the Canal Zone, the ICC provided no food, and workers had to fend for themselves, obtaining poor-quality food at inflated prices from Panamanian merchants. When Stevens arrived in 1905, he ordered food to be provided at cost, leading to the establishment of the Canal Zone Commissary. The functions of the Commissary quickly grew, generally against the will of the Panamanian government, which saw more and more goods and services provided in the Zone rather than in Panama. Merchants could not compete with the commissary's prices or quality; for example, it boasted that the meat it sold had been refrigerated every moment from the Chicago slaughterhouse to the moment it was passed to the consumer. By 1913, it consisted of 22 general stores, 7 cigar stores, 22 hostels, 2 hotels, and a mail-order division. It served high-quality meals at small expense to workers and more expensive meals to upper-echelon canal employees and others able to afford it.[39]

The commissary was a source of friction between the Canal Zone and Panama for several other reasons. The commissary dominated sales of supplies to passing ships.[40] The commissary was off limits to individuals who were not in the U.S. Military, employees of the Panama Canal Company, the Canal Zone Government and/or their dependents. This restriction was requested by Panama for the benefit of Panamanian storekeepers, who feared the loss of trade. Panama had laws restricting imports from the Canal Zone. Goods from the commissary would sometimes show up in Panamanian stores and in vendor displays, where Comisariato goods were deemed of high quality.[41] Additionally, there were separate commissaries on the U.S. military installations that were available only to the U.S. Military personnel and their dependents. Employees and dependents of the Panama Canal Company/Government were not allowed to utilize the commissaries, exchanges, package stores, theaters, gas stations, and other facilities on the U.S. Military installations.

Citizenship

Although the Panama Canal Zone was legal territory of the United States[42] until the implementation of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties in 1979, questions arose almost from its inception as to whether it was considered part of the United States for constitutional purposes, or, in the phrase of the day, whether the Constitution followed the flag. In 1901 the US Supreme Court had ruled in Downes v. Bidwell that unincorporated territories are not the United States.[43] On July 28, 1904, Controller of the Treasury Robert Tracewell stated, "While the general spirit and purpose of the Constitution is applicable to the zone, that domain is not a part of the United States within the full meaning of the Constitution and laws of the country."[44] Accordingly, the Supreme Court held in 1905 in Rasmussen v. United States that the full Constitution only applies for incorporated territories of the United States.[45]

The treaty with Panama made no mention of the nationality status of the native inhabitants of the Zone.[46] Pursuant to the principles of international law, they became non-citizen U.S. nationals unless they elected to retain their previous nationality. Children of non-citizen U.S. nationals generally acquired the status of their parents. However, for most nationality purposes, the Canal Zone was considered to be foreign territory and the status persons acquired at birth was governed by Sec. 1993 of the Revised Statutes of the United States (Act of February 10, 1855, 10 Stat. 604),[47] which granted them statutory US citizenship at birth but only if their fathers were, at the time of the child's birth, U.S. citizens who had previously resided in the United States. In 1934 the law was amended to allow for citizenship to be acquired at birth through either parent if the parent was a U.S. citizen who had previously resided in the United States. In 1937 a new law (Act of August 4, 1937, 50 Stat. 558)[48] was enacted to provide for US citizenship to persons born in the Canal Zone (since 1904) to a U.S. citizen parent without that parent needing to have been previously resident in the United States.[42] The law is now codified under title 8, section 1403.[49] It not only grants statutory and declaratory born citizenship to those born in the Canal Zone after February 26, 1904, of at least one US citizen parent, but also does so retroactively for all children born of at least one US citizen in the Canal Zone before the law's enactment.[50]

In 2008, during a minor controversy over whether John McCain, born in the Zone in 1936, was legally eligible for the presidency, the US Senate passed a non-binding resolution that McCain was a "natural-born Citizen" of the United States.[51]

Notable people

- Leo Barker (born 1959) American football player, born in Colón, Panama Canal Zone.

- Earl Bell (born 1955) American Olympic pole vaulter, born in the Panama Canal Zone.[52]

- Frederick C. Blesse (1921–2012), United States Air Force major general and flying ace, born in Colón, Panama Canal Zone.

- Rod Carew (born 1945) Panamanian former Major League Baseball (MLB) first baseman, second baseman and coach who played from 1967 to 1985 for the Minnesota Twins and the California Angels, born in Gatún, Panama Canal Zone.

- Kenneth B. Clark (1914–2005), American psychologist who, as a married team, conducted research among children and were active in the Civil Rights Movement; he was born in Panama Canal Zone.

- John G. Claybourn (1886–1967), civil engineer and Dredging Division Superintendent of the Isthmian Canal Commission. He was the original designer of Gamboa, Panama.

- The Del Rubio Triplets (1921–1996, 2001, 2011), Edith, Elena, and Mildred Boyd triplets, singers, born in Ancón, Panama Canal Zone.[53]

- Bill Dunn (born 1961), American politician, a Republican, and the former Acting-Speaker of the Tennessee House of Representatives.

- Charles Patrick Garcia (born 1961), He grew up in Panama City and graduated from Balboa High School.

- Ernest Hallen (1875–1947), American who work as the official photographer of the Panama Canal.

- John Hayes (born 1955), American former professional tennis player; he was born in Panama Canal Zone.

- George Headley (1909–1983), West Indian cricketer, born in Colón, Panama Canal Zone.

- Jeff Hennessy (1929–2015), American trampoline coach and physical educator.

- Tom Hughes (1934–2019), American retired professional baseball player appeared in two games for the 1959 St. Louis Cardinals of Major League Baseball; born in Ancón, Panama Canal Zone.

- Karen Hughes (born 1956), American politician and businesswomen, the daughter of Harold Parfitt, the last U.S. Governor of the Panama Canal Zone.

- Norman Seaton Ives (1923–1978), American artist, graphic designer, educator, and fine art publisher; born in the Panama Canal Zone.[54]

- Eric Jackson (born 1952), American politician, journalist, and radio talk show host; born in Colón, Panama Canal Zone and resided there from 1952 to June 1966.

- Thomas H. Jordan (born 1948), American seismologist, and former director (2002 to 2017) of the Southern California Earthquake Center at The University of Southern California.

- Shoshana Johnson (born 1973), Panamanian-born former United States soldier, and the first black female prisoner of war in the military history of the United States.

- Stephen J. Kopp (1951–2014), American educator and former president of Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia from 2005 to 2014.

- John McCain (1936–2018), the Republican 2008 presidential nominee and former US Senator from Arizona; born at the Coco Solo Naval Air Station in the Panama Canal Zone.[55]

- Gustavo A. Mellander, noted historian and expert on Panamanian history and seasoned university administrator; graduate of Balboa High School and the Canal Zone Junior College.Congressional Record, House of Representatives, April 23, 1985, Wash. DC}

- Edward A. Murphy Jr. (1918–1990), American aerospace engineer, for whom Murphy's law is named; born in the Panama Canal Zone.

- John S. Palmore (1917–2017), American judge; served as the Chief Justice of the Kentucky Supreme Court; born in the Panama Canal Zone.

- Richard Prince (born 1949), American painter and photographer; born in the Panama Canal Zone.[56]

- Thomas Sancton Sr. (1915–2012), American novelist and journalist.

- Manny Sanguillén (Born 1944), American Major League Baseball MLB Catcher, for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

- Klea Scott, (born 1968), Canadian actress, born in Panama City, Panama Canal Zone.[57]

- Louis E. Sola (born 1968), Commissioner of the Federal Maritime Commission, raised in Panama Canal Zone.

- Charles S. Spencer (born 1950), American curator and anthropologist, born in Panama Canal Zone.

- Sage Steele (born 1972), American television anchor, born in Panama Canal Zone and spend early childhood there, she is from a U.S. Army family.[58]

- Stephen Stills (born 1945), musician, graduated from Lincoln High School.[59]

- Hillary Waugh (1920–2008), mystery writer, who served in the United States Navy as an air pilot in the Panama Canal Zone.[60]

Culture

Frederick Wiseman made the film Canal Zone, which was released and aired on PBS in 1977.[61]

Townships and military installations

The Canal Zone was generally divided into two sections, the Pacific side and the Atlantic side, separated by Gatun Lake.

A partial list of Canal Zone townships and military installations:[62]

Townships

- Ancón – built on the lower slopes of Ancon Hill, adjacent to Panama City. Also home to Gorgas Hospital.

- Balboa – the Zone's administrative capital, as well as location of the harbor and main Pacific-side high school.

- Balboa Heights

- Cardenas – as the Canal Zone was gradually handed over to Panamanian control, Cardenas was one of the last Zonian holdouts.

- Cocoli

- Corozal – site of the Pacific side cemetery

- Curundú – on a military base, but housed civilian military workers, also home to the Junior High School for the Pacific Side

- Curundu Heights

- Diablo

- Diablo Heights

- Gamboa – headquarters of dredging division, located on Gatun Lake. Many new arrivals to the Canal Zone were assigned here.

- La Boca – home of the Panama Canal College.

- Los Rios

- Paraíso

- Pedro Miguel

- Red Tank – abandoned and allowed to be overgrown around 1950.

- Rosseau – built as a naval hospital during World War II, housed FAA personnel until Cardenas was built. Torn down after about 20 years.

Military installations

- Forts Amador, Grant, and Kobbe were the Harbor Defenses of Balboa of the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps from 1912 through 1948

- Fort Amador – on the coast, partly built on land extended into the sea using excavation materials from the canal construction

- Fort Grant - coastal artillery fort, on an island chain extending seaward from Fort Amador

- Fort Clayton – on the east side of the canal, it was the headquarters of the 193rd Infantry and the Southern Command Network (SCN), an American Forces Radio and Television Service (AFRTS) outlet.

- Corozal Army Post – close to, but separate from, the civilian township.

- Fort Kobbe - coastal artillery fort

- Rodman Naval Station (which includes the Marine Barracks)

- Albrook Air Force Base

- Howard Air Force Base

- Quarry Heights – headquarters of the United States Southern Command.

Townships

- Brazos Heights: privately owned housing (by United Brands and other, mostly shipping companies) where employees and owners of shipping agencies, lawyers, and the head of the YMCA lived.

- Coco Solo – main hospital and site of the only Atlantic-side high school, Cristobal High School.

- Cristóbal – main harbor and port.

- Gatún

- Margarita

- Mount Hope – site of the only Atlantic-side cemetery and drydock.

- Rainbow City, now Arco Iris

Military installations

- Forts Randolph, De Lesseps, and Sherman were the Harbor Defenses of Cristobal of the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps from 1912 through 1948

- Fort Gulick – home to the School of the Americas.

- Galeta Island

- Fort Randolph – coastal artillery fort, located on Margarita Island in Manzanillo Bay.

- Fort De Lesseps – coastal artillery fort located in Colón.

- Fort Davis

- France Field

- Fort Sherman – built as a coastal artillery fort, later home to the Jungle Operations Training Center.

Panama Canal Treaty implementation

On 1 October 1979, the day the Panama Canal Treaty of 1977 took effect, most of the land within the former Canal Zone was transferred to Panama. However, the treaty set aside many Canal Zone areas and facilities for transfer during the following 20 years. The treaty specifically categorized areas and facilities by name as "Military Areas of Coordination", "Defense Sites" and "Areas Subject to Separate Bilateral Agreement". These were to be transferred by the U.S. to Panama during certain time windows or simply by the end of the 243-month treaty period. On 1 October 1979, among the many such parcels so designated in the treaty, 35 emerged as enclaves (surrounded entirely by land solely under Panamanian jurisdiction).[63] In later years as other areas were turned over to Panama, nine more enclaves emerged.

At least 13 other parcels each were enclosed partly by land under the absolute jurisdiction of Panama and partly by an "Area of Civil Coordination" (housing), which under the treaty was subject to elements of both U.S. and Panamanian public law. In addition, the 1977 treaty designated numerous areas and individual facilities as "Canal Operating Areas" for joint U.S.-Panama ongoing operations by a commission. On the effective date of the treaty, many of these, including Madden Dam, became newly surrounded by the territory of Panama. Just after noon local time on 31 December 1999, all former Canal Zone parcels of all types had come under the exclusive jurisdiction of Panama.[64][65][66][67][68][69]

The 44 enclaves of U.S. territory that existed under the treaty are shown in the table below.

Enclave name Type (military/civil)* Function Date created Date transferred PAD (former Panama Air Depot) Area Bldg. 1019 (Defense Mapping Agency) military logistics 1 October 1979 1 October 1980 PAD Area Bldg. 1007 (Inter-American Geodetic Survey Headquarters) military logistics 1 October 1979 1 October 1980 PAD Area Bldg. 1022 (warehouse) military logistics 1 October 1979 1 October 1980 PAD Area Bldg. 490 (U.S. Army Meddac Warehouse) military logistics 1 October 1979 1 October 1981 PAD Area Bldg. 1010 (U.S. Army Meddac Warehouse) military logistics 1 October 1979 1 October 1981 PAD Area Bldg. 1008 (AAFES Warehouse) military logistics 1 October 1979 1 October 1982 PAD Area Bldg. 1009 (AAFES Warehouse) military logistics 1 October 1979 1 October 1982 Curundu Antenna Farm military communications 1 October 1979 1 October 1982 Curundu Heights military housing 1 October 1979 1 October 1982 France Field housing (15 units) on McEwen St. military housing 1 October 1979 1 October 1984 Navy Salvage Storage Area (Balboa) military logistics 1 October 1979 1 October 1984 Coco Solo Hospital civil medical 1 October 1979 31 May 1993 Ft. Amador Service Club Bldg. 107 military base 1 October 1979 1 October 1996 Ft. Amador Bldg. 105 complex military base 1 October 1979 1 October 1996 FAA Long Range Radar, Semaphore Hill (coordinates 485035) civil aviation 1 October 1979 13 December 1996 Ancon Hill: Bldg. 140 (coordinates 595904) military logistics 1 October 1979 8 January 1998 Ancon Hill: Bldg. 159 – Quarry Heights Motor Pool military logistics 1 October 1979 8 January 1998 Ancon Hill FAA microwave link repeater station, Bldg. 148 (coordinates 594906) civil aviation 1 October 1979 16 January 1998 Ancon Hill FAA VHF/UHF communications station (coordinates 595902) civil aviation 1 October 1979 16 January 1998 Piña Range (part) military training 1 October 1979 30 June 1999 Balboa High School Shop Bldg. civil school 1 October 1979 31 August 1999 Balboa High School Activities Bldg. civil school 1 October 1979 31 August 1999 Cerro Gordo communications site military communications 1 October 1979 31 August 1999 Howard AFB/Ft. Kobbe Complex military base 1 October 1979 1 November 1999 Military Traffic Management Command, Bldg 1501, Balboa/Pier 18 military logistics 1 October 1979 22 December 1999 Army Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Chambers (in current Parque Natural Metropolitano) military research 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 Federal Aviation Administration Bldg. 611 civil aviation 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 FAA radar station, Isla Perico civil aviation 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 Stratcom Transmitter Station Bldg. 430 (in Corozal Antenna Field) military communications 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 Stratcom Transmitter Station Bldg. 433 (in Corozal Antenna Field) military communications 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 Stratcom Transmitter Station Bldg. 435 (in Corozal Antenna Field) military communications 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 Army Transport Shipping Facility (Balboa) military logistics 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 Navy Communications Electric Repair Facility (Balboa) military communications 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 U.S. Air Force Communications Group storage/training facility, Bldg 875 military logistics 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 Inter-American Air Force Academy Jet Engine Test Cell, Bldg. 1901 military research 1 October 1979 31 December 1999 Bachelor Officers' Housing (larger parcel) – Curundu Heights military housing 2 October 1982 Nov–Dec 1992 Bachelor Officers' Housing (smaller parcel) – Curundu Heights military housing 2 October 1982 Nov–Dec 1992 Curundu Laundry facility military housing 2 October 1982 15 November 1999 Ft. Gulick Elementary School civil school 2 October 1984 1 September 1995 Ft. Gulick Ammunition Storage Facility military logistics 2 October 1984 1 September 1995 Cristobal Junior-Senior High School civil school 1990 1 September 1995 Chiva Chiva Antenna Farm (Foreign Broadcast Information Service) military communications 1993 6 January 1998 Curundu Middle School civil school 1 August 1997 15 September 1999 Piña Range (remainder) military training 30 June 1999 1 July 1999 - * Enclaves are a subset of those areas that were categorized in the 1977 Panama Canal Treaty as "Military Area of Coordination", "Defense Site" and "Area Subject to Separate Bilateral Agreement". The map legends and color coding that are contained in the Panama Canal Treaty Annex provide visual corroborations of the treaty language.

Postage stamps

The Panama Canal Zone issued its own postage stamps from 1904 until October 25, 1978.[70] During the early years, United States postage stamps overprinted "Canal Zone" were used. After a few years, accredited Canal Zone stamps were issued. After a transition period during which Panama took over the administration of postal service, Canal Zone stamps became invalid.

The two-letter state abbreviation for mail sent to the Zone was CZ.

Amateur radio

Amateur radio licenses were issued by the United States Federal Communications Commission and carried the prefix KZ5, the initial 'K' indicating a station under American jurisdiction.[71] The American Radio Relay League had a Canal Zone section, and the Canal Zone was considered an entity for purposes of the DX Century Club. Contacts with Canal Zone stations from before repatriation may still be counted for DXCC credit separate from Panama.[72] The KZ5 amateur radio prefix has been issued to license operators since 1979 but today has no special meaning.

See also

- Martyrs' Day (Panama)

- Panama Railway

- Rail transport in Panama

- Transcontinental Railroad#Panama

- List of former United States military installations in Panama

- List of Governors of Panama Canal Zone

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Canal Zone

References

- Liptak, Adam (July 11, 2008). "A Hint of New Life to a McCain Birth Issue". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- "Panamanian Control", Panama Canal, infoplease.com, archived from the original on May 24, 2008, retrieved June 2, 2008

- Maurer and Yu, pp. 15–18.

- Major, p. 9.

- Major, p. 11.

- Maurer and Yu, pp. 33–34.

- Maurer and Yu, pp. 35–36.

- Major, p. 13.

- Major, pp. 15–16.

- Major, pp. 18–24.

- Major, pp. 24–28.

- Maurer and Yu, p. 76.

- Maurer and Yu, pp. 78–82.

- Maurer and Yu, pp. 82–86.

- McCullough, pp. 397–399, 402.

- NARA: 185.6 RECORDS OF THE SECOND ISTHMIAN CANAL COMMISSION 1904–16.

- Wilson, Executive Order 1885.

- Conn, Stetson; Engelman, Rose C.; Fairchild, Byron (1964). The Western Hemisphere—Guarding The United States And Its Outposts. United States Army In World War II. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. p. 312. LCCN 62060067.

- Code of Federal Regulations, Title 3—The President 1938—1943 Compilation. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service. 1968. p. 569.

- NARA: RECORDS OF THE CANAL ZONE GOVERNMENT AND THE PANAMA CANAL COMPANY 1904–84.

- Panama Canal Treaty.

- Maurer & Yu 2011, p. 251.

- Maurer & Yu 2011, p. 252.

- The Panama Canal Review, February 1, 1952, p. 1.

- The Panama Canal Review, February 1, 1952, pp. 1, 13.

- The Panama Canal Review, February 1, 1952, p. 13.

- Greene, p. 62.

- Major, pp. 78–81.

- Greene, p. 63.

- Maurer and Yu, p. 111.

- Maurer & Yu, pp. 111–112.

- Kaysha Lisbeth Corinealdi, "Redefining Home: West Indian Panamanians and Transnational Politics of Race, Citizenship, and Diaspora, 1928–1970" (PhD diss., Yale University, 2011), 43.

- Corinealdi, 2011, pp. 44–45

- "Canal Zone Workers Rally to CIO: Plan Program," Chicago Defender, August 31, 1946.

- Corinealdi, 2011, pp. 47–48

- Michael Conniff, Black Labor on a White Island: Panama, 1904–1981 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985), 113.

- Frank Gurridy, Forging Diaspora: Afro-Cubans and African Americans (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 5.

- McCullough, pp. 478–79.

- Maurer and Wu, pp. 192–94.

- Maurer and Wu, pp. 194–96.

- Knapp and Knapp, pp. 183–84.

- "7 FAM 1120: Acquisition of US nationality in US territories and possessions". Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- United States Supreme Court, Downes v. Bidwell Archived September 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- "Not Part of United States" (PDF), The New York Times, July 29, 1904, retrieved June 2, 2008|

- United States Supreme Court, Archived November 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- "Once a Zonian: the Americans who called the Panama Canal home", Radio Netherlands Archives, March 7, 2004

- "8 FAM 302.4 SPECIAL CITIZENSHIP PROVISIONS REGARDING PANAMA". 8 FAM 302.4 SPECIAL CITIZENSHIP PROVISIONS REGARDING PANAMA. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- "Act of August 4, 1937 (50 Stat. 558)" (PDF). Legisworks. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- 8 U.S.C. § 1403

- Cf. 8 U.S.C. § 1403, paragraph (a): "whether before or after the effective date of this chapter".

- Impomeni, Mark. Clinton, Obama Sponsor McCain Citizenship Bill. PoliticsDaily.com. May 2008. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- "Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- "Last member of San Pedro's Del Rubio Triplets dies at 89". Daily Breeze. August 9, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- "Norman Ives, 54; Graphic Designer And Yale Teacher". The New York Times. February 4, 1978. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- "There was a very real 'birther' debate about John McCain". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- "Richard Prince: Canal Zone at Gagosian Gallery". Musée Magazine. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- Johnson, Allan (November 10, 1998). "Gruesome Details". Chicago Tribune.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Wollschlager, Mike (May 18, 2018). "ESPN's Sage Steele Renovates an Avon Colonial into a Dream Home". Connecticut Magazine. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- "Music Memories: Happy Birthday, Stephen Stills!". www.lapl.org. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- "Obituary: Hillary Waugh". The Guardian. March 11, 2009. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- Eames, David (October 2, 1977). "Watching Wiseman Watch". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- Johnson, Suzanne P. American legacy in Panama: a brief history of the Department of Defense installations and properties. United States Army South. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- Treaty concerning the permanent neutrality and operation of the Panama Canal, with annexes and protocol. Signed at Washington September 7, 1977. Entered into force October 1, 1979, subject to amendments, conditions, reservations, and understandings. 33 UST 1; TIAS 10029 Archived April 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine; 1161 UNTS 177.

- United States. Central Intelligence Agency. (1987). "Land and waters of the Panama Canal Treaty (map)". Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- "Carte IV. Aires de terre et d'eau mises à disposition du fonctionnement et de la défense du canal de Panama par le traité relatif au canal de Panama du 7 septembre 1977". Dirección ejecutiva para los asuntos del tratado (DEPAT). Ciudad de Panama. 1981. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- Panama Canal Treaty: Implementation of Article IV (TIAS 10032). United States Treaties and Other International Agreements. Vol. 33. United States Department of State. 1987. pp. 307–432. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- Ormsbee, William H. "PANAMA CANAL TREATY TRANSITION (OCTOBER 1979 – DECEMBER 1999)". Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- Ormsbee, William H. "PANAMA CANAL TREATY TRANSITION – MILITARY. SUMMARY OF MILITARY PROPERTY TRANSFERS AND MILITARY FORCES DRAWDOWN". Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- "Canal Zone Map Section. Curundu 1". Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- Rossiter, Stuart & John Flower. The Stamp Atlas. London: Macdonald, 1986, p. 166. ISBN 0356108627

- Company, Panama Canal (1963). The Panama Canal review. Panama Canal Co. p. 103. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- "ARRL DXCC LIST – DELETED ENTITIES" (PDF). American Radio Relay League. May 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

Further reading and viewing

- "More American than America". Time. January 24, 1964.

- "PANAMA: No More Tomorrows". Time. October 15, 1979.

- Dimock, Marshall E. (1934) Government-operated enterprise in the Panama Canal Zone (University of Chicago Press) online.

- Donoghue, Michael E. (2014). Borderland on the Isthmus: Race, Culture, and the Struggle for the Canal Zone. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Frenkel, Stephen. (2002) "Geographical representations of the 'Other': the landscape of the Panama Canal Zone." Journal of Historical Geography 28.1 (2002): 85–99, covers 1910–1940.

- Greene, Julie (2009). The Canal Builders: Making America's Empire at the Panama Canal. New York: The Penguin Press.

- Greene, Julie. (2004) "Spaniards on the Silver roll: Labor troubles and Liminality in the Panama Canal Zone, 1904–1914." International Labor and Working-Class History 66 (2004): 78–98.

- Harding, Robert C. (2001). Military Foundations of Panamanian Politics. Transaction Publishers.

- Harding, Robert C. (2006). The History of Panama. Greenwood Publishing.

- Governments of the United States of America and the Republic of Panama. "Panama Canal Treaty". Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- Knapp, Herbert and Knapp, Mary (1984). Red, White and Blue Paradise: The American Canal Zone in Panama. San Diego: Harcourt, Brace, and Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-176135-3.

- Major, John (1993). Prize Possession: The United States and the Panama Canal, 1903–1979. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52126-0.

- Maurer, Noel; Yu, Carlos (2011). The Big Ditch: How America Took, Built, Ran, and Ultimately Gave Away the Panama Canal. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14738-3. LCCN 2010029058. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- McCullough, David (1977). The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-24409-5.

- Mellander, Gustavo A., Mellander, Nelly, Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390. (1999)

- Mellander, Gustavo A., The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years." Danville, Ill.: Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568. (1971)

- NARA. "185.6 RECORDS OF THE SECOND ISTHMIAN CANAL COMMISSION 1904–16—History". National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- NARA. "185.8 RECORDS OF THE CANAL ZONE GOVERNMENT AND THE PANAMA CANAL COMPANY 1904–84—History". National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- "Canal Company to go on Break Even Basis". The Panama Canal Review. February 1, 1952. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- Wiseman, Frederick (1977). Canal Zone (motion picture). Zipporah Films.

- Woodrow Wilson (January 27, 1914). "Executive Order 1885 - To Establish a Permanent Organization for the Operation and Government of the Panama Canal". President of the United States. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

External links

- Official Handbook of the Panama Canal—1915

- Governor Parfitt's Address at Flag-lowering Ceremonies September 30, 1979

- Maps of the Canal Zone

- Live Panama Canal webcams

- Air Defense of the Panama Canal 1958–1970

- Panama & the Canal Digital Collection

- Panama Canal Centennial Online Exhibit

- Medicine in the Panama Canal Zone: The Samuel Taylor Darling Memorial Library Archives