Oregon Territory

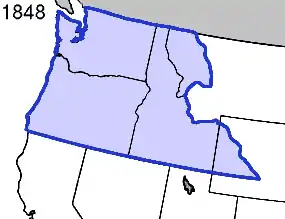

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Originally claimed by several countries (see Oregon Country), the region was divided between the UK and the US in 1846. When established, the territory encompassed an area that included the current states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, as well as parts of Wyoming and Montana. The capital of the territory was first Oregon City, then Salem, followed briefly by Corvallis, then back to Salem, which became the state capital upon Oregon's admission to the Union.

| Territory of Oregon | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organized incorporated territory of the United States | |||||||||||

Seal of the Oregon Territory | |||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||

| • Type | Organized incorporated territory | ||||||||||

| • Motto | Alis volat propriis | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1848–1850; 1853 | Joseph Lane | ||||||||||

• 1850 | Kintzing Prichette | ||||||||||

• 1850–1853 | John P. Gaines | ||||||||||

• 1853–1854 | John W. Davis | ||||||||||

• 1854–1859 | George L. Curry | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| June 15, 1846 | |||||||||||

• Organized | August 14 1848[1] | ||||||||||

• Washington Territory split off | March 2, 1853 | ||||||||||

| February 14, 1859 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Background

Originally inhabited by Native Americans, the region that became the Oregon Territory was explored by Europeans first by sea. The first documented voyage of exploration was made in 1777 by the Spanish, and both British and American vessels visited the region not long thereafter.[2][3] Subsequent land-based exploration by Alexander Mackenzie and the Lewis and Clark Expedition and development of the fur trade in the region strengthened the competing claims of Great Britain and the United States.[4]

The competing interests of the two foremost claimants were addressed in the Treaty of 1818, which sanctioned a "joint occupation", by British and Americans, of a vast "Oregon Country" (as the American side called it) that comprised the present-day U.S. states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, parts of Montana and Wyoming, and the portion of what is now the Canadian province of British Columbia south of the parallel 54°40′ north.[5]

Formation

During the period of joint occupation, most activity in the region outside of the activities of the indigenous people came from the fur trade, which was dominated by the British Hudson's Bay Company.[6] Over time, some trappers began to settle down in the area and began farming, and missionaries started to arrive in the 1830s.[6] Some settlers also began arriving in the late 1830s, and covered wagons crossed the Oregon Trail beginning in 1841.[7] At that time, no government existed in the Oregon Country, as no one nation held dominion over the territory.

A group of settlers in the Willamette Valley began meeting in 1841 to discuss organizing a government for the area.[8] These earliest documented discussions, mostly concerning forming a government, were held in an early pioneer and Native American encampment and later town known as Champoeg, Oregon.[8] These first Champoeg Meetings eventually led to further discussions, and in 1843 the creation of the Provisional Government of Oregon.[8] In 1846, the Oregon boundary dispute between the U.S. and Britain was settled with the signing of the Oregon Treaty.[5]

The United States federal government left their part of the region unorganized for two years until news of the Whitman massacre reached the United States Congress and helped to facilitate the organization of the region into a U.S. territory.[9] On August 14, 1848, Congress passed the Act to Establish the Territorial Government of Oregon, which created what was officially the Territory of Oregon.[9] The Territory of Oregon originally encompassed all of the present-day states of Idaho, Oregon and Washington, as well as those parts of present-day Montana and Wyoming west of the Continental Divide.[9] Its southern border was the 42nd parallel north (the boundary of the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819), and it extended north to the 49th parallel. Oregon City, Oregon, was designated as the first capital.[10]

Government

The territorial government consisted of a governor, a marshal, a secretary, an attorney, and a three-judge supreme court.[9] Judges on the court also sat as trial level judges as they rode circuit across the territory.[9] All of these offices were filled by appointment by the President of the United States.[9] The two-chamber Oregon Territorial Legislature was responsible for passing laws, with seats in both the upper-chamber council and lower-chamber house of representatives filled by local elections held each year.[9]

Taxation took the form of an annual property tax of 0.25% for territorial purposes with an additional county tax not to exceed this amount.[11] This tax was to be paid on all town lots and improvements, mills, carriages, clocks and watches, and livestock; farmland and farm products were not taxed.[11] In addition, a poll tax of 50 cents for every qualified voter under age 60 was assessed and a graduated schedule of merchants' licenses established, ranging from the peddlar's rate of $10 per year to a $60 annual fee on firms with more than $20,000 of capital.[11]

Gaining statehood

Oregon City served as the seat of government from 1848 to 1851, followed by Salem from 1851 to 1855. Corvallis served briefly as the capital in 1855, followed by a permanent return to Salem later that year.[12] In 1853, as a result of the Monticello Convention and its approval by Congress and President Millard Fillmore, the portion of the territory north of the lower Columbia River and north of the 46th parallel east of the river was organized into the Washington Territory.[13] [14] The Oregon Constitutional Convention was held in 1857 to draft a constitution in preparation for becoming a state, with the convention delegates approving the document in September, and then general populace approving the document in November.[15]

In 1850, 10 years after the end of the Second Great Awakening (1790–1840), of the 9 churches with regular services in the Oregon Territory, 5 were Catholic, 1 was Baptist, 1 was Congregational, 1 was Methodist, and 1 was Presbyterian.[16] In the 1850 United States census, 10 counties in the Oregon Territory (7 counties in contemporary Oregon and 3 in contemporary Washington) reported the following population counts:[17][18]

| Rank | County | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marion | 2,749 |

| 2 | Washington | 2,652 |

| 3 | Clackamas | 1,859 |

| 4 | Yamhill | 1,512 |

| 5 | Polk | 1,051 |

| 6 | Linn | 994 |

| 7 | Benton | 814 |

| 8 | Clark | 643 |

| 9 | Lewis | 558 |

| 10 | Clatsop | 462 |

| Oregon Territory | 13,294 | |

On February 14, 1859, the territory entered the Union as the U.S. state of Oregon within its current boundaries.[15] The remaining eastern portion of the territory (the portions in present-day southern Idaho and western Wyoming) was added to the Washington Territory.

See also

- Historic regions of the United States

- Territorial evolution of the United States

References

- 9 Stat. 323

- Howard M. Corning, ed. (1989). Dictionary of Oregon History. Binfords & Mort Publishing. p. 110.

- Horner, John B. (1919). Oregon: Her History, Her Great Men, Her Literature. The J.K. Gill Co.: Portland. pp. 28–29.

- Horner, pp. 53–59.

- Corning, p. 129.

- Horner, pp. 60–64.

- Corning, p. 186.

- Corning, p. 206.

- Corning, p. 240.

- Writers' Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Oregon (1940). Oregon: End of the Trail. American Guide Series. Portland, Oregon: Binfords & Mort. p. 191. OCLC 4874569.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1886). . The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: Volume 29: History of Oregon: Volume 1, 1834-1848. San Francisco: The History Company. p. 540.

- Horner, p. 162.

- The History of the Pacific Northwest Oregon and Washington 1889: Volume I. Portland: North Pacific History Company. 1889.

- Horner, p. 153.

- Horner, p. 166.

- Selcer, Richard F. (2006). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Civil War America: 1850 to 1875. New York: Facts on File. p. 143. ISBN 978-0816038671.

- Forstall, Richard L. (ed.). Population of the States and Counties of the United States: 1790–1990 (PDF) (Report). United States Census Bureau. pp. 134–135. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Forstall, Richard L. (ed.). Population of the States and Counties of the United States: 1790–1990 (PDF) (Report). United States Census Bureau. pp. 176–177. Retrieved May 18, 2020.