Carbene

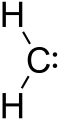

In organic chemistry, a carbene is a molecule containing a neutral carbon atom with a valence of two and two unshared valence electrons. The general formula is R−:C−R' or R=C: where the R represents substituents or hydrogen atoms.

The term "carbene" may also refer to the specific compound :CH2, also called methylene, the parent hydride from which all other carbene compounds are formally derived.[1][2] Carbenes are classified as either singlets or triplets, depending upon their electronic structure. Most carbenes are very short lived, although persistent carbenes [3] are known. One well-studied carbene is dichlorocarbene Cl2C:, which can be generated in situ from chloroform and a strong base.

Structures and bonding

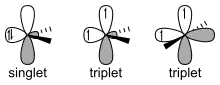

The two classes of carbenes are singlet and triplet carbenes. Singlet carbenes are spin-paired. In the language of valence bond theory, the molecule adopts an sp2 hybrid structure. Triplet carbenes have two unpaired electrons. Most carbenes have a nonlinear triplet ground state, except for those with nitrogen, oxygen, or sulphur, and halides substituents bonded to the divalent carbon. Substituents that can donate electron pairs may stabilize the singlet state by delocalizing the pair into an empty p orbital. If the energy of the singlet state is sufficiently reduced it will actually become the ground state.

Bond angles are 125–140° for triplet methylene and 102° for singlet methylene (as determined by EPR).

For simple hydrocarbons, triplet carbenes usually are 8 kcal/mol (33 kJ/mol) more stable than singlet carbenes. The stabilization is in part attributed to Hund's rule of maximum multiplicity.

Strategies for stabilizing triplet carbenes are elusive. The carbene called 9-fluorenylidene has been shown to be a rapidly equilibrating mixture of singlet and triplet states with an approximately 1.1 kcal/mol (4.6 kJ/mol) energy difference.[4] It is, however, debatable whether diaryl carbenes such as the fluorene carbene are true carbenes because the electrons can delocalize to such an extent that they become in fact biradicals. In silico experiments suggest that triplet carbenes can be thermodynamically stabilized with electropositive heteroatoms such as in silyl and silyloxy carbenes, especially trifluorosilyl carbenes.[5]

Reactivity

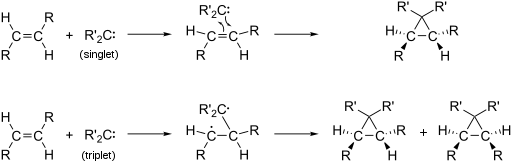

Singlet and triplet carbenes exhibit divergent reactivity. Singlet carbenes generally participate in cheletropic reactions as either electrophiles or nucleophiles. Singlet carbenes with unfilled p-orbital should be electrophilic. Triplet carbenes can be considered to be diradicals, and participate in stepwise radical additions. Triplet carbenes have to go through an intermediate with two unpaired electrons whereas singlet carbene can react in a single concerted step.

Due to these two modes of reactivity, reactions of singlet methylene are stereospecific whereas those of triplet methylene are stereoselective. This difference can be used to probe the nature of a carbene. For example, the reaction of methylene generated from photolysis of diazomethane with cis-2-butene or with trans-2-butene each give a single diastereomer of the 1,2-dimethylcyclopropane product: cis from cis and trans from trans, which proves that the methylene is a singlet.[6] If the methylene were a triplet, one would not expect the product to depend upon the starting alkene geometry, but rather a nearly identical mixture in each case.

Reactivity of a particular carbene depends on the substituent groups. Their reactivity can be affected by metals. Some of the reactions carbenes can do are insertions into C-H bonds, skeletal rearrangements, and additions to double bonds. Carbenes can be classified as nucleophilic, electrophilic, or ambiphilic. For example, if a substituent is able to donate a pair of electrons, most likely carbene will not be electrophilic. Alkyl carbenes insert much more selectively than methylene, which does not differentiate between primary, secondary, and tertiary C-H bonds.

Cyclopropanation

Carbenes add to double bonds to form cyclopropanes. A concerted mechanism is available for singlet carbenes. Triplet carbenes do not retain stereochemistry in the product molecule. Addition reactions are commonly very fast and exothermic. The slow step in most instances is generation of carbene. A well-known reagent employed for alkene-to-cyclopropane reactions is Simmons-Smith reagent. This reagent is a system of copper, zinc, and iodine, where the active reagent is believed to be iodomethylzinc iodide. The reagent is complexed by hydroxy groups such that addition commonly happens syn to such group.

C—H insertion

Insertions are another common type of carbene reactions. The carbene basically interposes itself into an existing bond. The order of preference is commonly:

- X–H bonds where X is not carbon

- C–H bond

- C–C bond.

Insertions may or may not occur in single step.

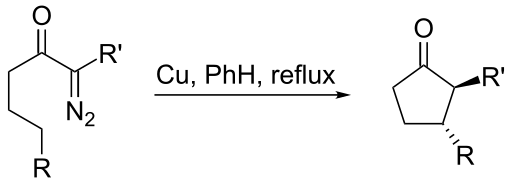

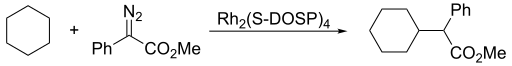

Intramolecular insertion reactions present new synthetic solutions. Generally, rigid structures favor such insertions to happen. When an intramolecular insertion is possible, no intermolecular insertions are seen. In flexible structures, five-membered ring formation is preferred to six-membered ring formation. Both inter- and intramolecular insertions are amendable to asymmetric induction by choosing chiral ligands on metal centers.

Carbene intramolecular reaction

Carbene intramolecular reaction

Carbene intermolecular reaction

Carbene intermolecular reaction

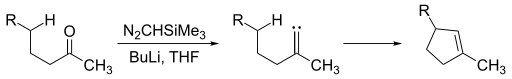

Alkylidene carbenes are alluring in that they offer formation of cyclopentene moieties. To generate an alkylidene carbene a ketone can be exposed to trimethylsilyl diazomethane.

Alkylidene carbene

Alkylidene carbene

Carbene dimerization

Carbenes and carbenoid precursors can undergo dimerization reactions to form alkenes. While this is often an unwanted side reaction, it can be employed as a synthetic tool and a direct metal carbene dimerization has been used in the synthesis of polyalkynylethenes.

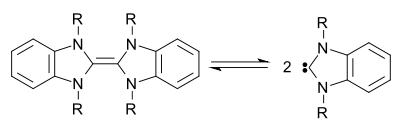

Persistent carbenes exist in equilibrium with their respective dimers. This is known as the Wanzlick equilibrium.

Carbene ligands in organometallic chemistry

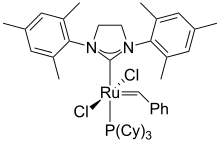

In organometallic species, metal complexes with the formulae LnMCRR' are often described as carbene complexes.[7] Such species do not however react like free carbenes and are rarely generated from carbene precursors, except for the persistent carbenes. The transition metal carbene complexes can be classified according to their reactivity, with the first two classes being the most clearly defined:

- Fischer carbenes, in which the carbene is bonded to a metal that bears an electron-withdrawing group (usually a carbonyl). In such cases the carbenoid carbon is mildly electrophilic.

- Schrock carbenes, in which the carbene is bonded to a metal that bears an electron-donating group. In such cases the carbenoid carbon is nucleophilic and resembles Wittig reagent (which are not considered carbene derivatives).

- Carbene radicals, in which the carbene is bonded to an open-shell metal with the carbene carbon possessing a radical character. Carbene radicals have features of both Fischer and Schrock carbenes, but are typically long-lived reaction intermediates.

- N-Heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) [8] are derived by C-deprotonation imidazolium or dihydroimidazolium salts. They often are deployed as ancillary ligands in organometallic chemistry. Such carbenes are spectator ligands that are usually very strong sigma donors, often drawing comparisons to phosphines.[9][10] The ligands themselves, especially when they are isolated free of the metal, are sometimes known as Arduengo or Wanzlick carbenes.

Generation of carbenes

- A method that is broadly applicable to organic synthesis is induced elimination of halides from gem-dihalides employing organolithium reagents. It remains uncertain if under these conditions free carbenes are formed or metal-carbene complex. Nevertheless, these metallocarbenes (or carbenoids) give the expected organic products.

- R2CBr2 + BuLi → R2CLi(Br) + BuBr

- R2CLi(Br) → R2C + LiBr

- For cyclopropanations, zinc is employed in the Simmons–Smith reaction. In a specialized but instructive case, alpha-halomercury compounds can be isolated and separately thermolyzed. For example, the "Seyferth reagent" releases CCl2 upon heating.

- C6H5HgCCl3 → CCl2 + C6H5HgCl

- Most commonly, carbenes are generated from diazoalkanes, via photolytic, thermal, or transition metal-catalyzed routes. Catalysts typically feature rhodium and copper. The Bamford-Stevens reaction gives carbenes in aprotic solvents and carbenium ions in protic solvents.

- Base-induced elimination HX from haloforms (CHX3) under phase-transfer conditions.

- Photolysis of diazirines and epoxides can also be employed. Diazirines are cyclic forms of diazoalkanes. The strain of the small ring makes photoexcitation easy. Photolysis of epoxides gives carbonyl compounds as side products. With asymmetric epoxides, two different carbonyl compounds can potentially form. The nature of substituents usually favors formation of one over the other. One of the C-O bonds will have a greater double bond character and thus will be stronger and less likely to break. Resonance structures can be drawn to determine which part will contribute more to the formation of carbonyl. When one substituent is alkyl and another aryl, the aryl-substituted carbon is usually released as a carbene fragment.

- Carbenes are intermediates in the Wolff rearrangement

Applications of carbenes

A large scale application of carbenes is the industrial production of tetrafluoroethylene, the precursor to Teflon. Tetrafluoroethylene is generated via the intermediacy of difluorocarbene:[11]

- CHClF2 → CF2 + HCl

- 2 CF2 → F2C=CF2

The insertion of carbenes into C–H bonds has been exploited widely, e.g. the functionalization of polymeric materials[12] and electro-curing of adhesives.[13] The applications rely on synthetic 3-aryl-3-trifluoromethyldiazirines,[14][15] a carbene precursor that can be activated by heat,[16] light,[15][16] or voltage.[17][13]

History

Carbenes had first been postulated by Eduard Buchner in 1903 in cyclopropanation studies of ethyl diazoacetate with toluene.[18] In 1912 Hermann Staudinger[19] also converted alkenes to cyclopropanes with diazomethane and CH2 as an intermediate. Doering in 1954 demonstrated with dichlorocarbene synthetic utility.[20]

See also

- Transition metal carbene complexes

- Atomic carbon a single carbon atom with the chemical formula :C:, in effect a twofold carbene. Also has been used to make "true carbenes" in situ.

- Foiled carbenes derive their stability from proximity of a double bond (i.e. their ability to form conjugated systems).

- Carbene analogs and carbenoids

- Carbenium ions, protonated carbenes

- Ring opening metathesis polymerization

References

- Hoffmann, Roald (2005). Molecular Orbitals of Transition Metal Complexes. Oxford. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-853093-0.

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "carbenes". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C00806

- For detailed reviews on stable carbenes, see: (a) Bourissou, D.; Guerret, O.; Gabbai, F. P.; Bertrand, G. (2000). "Stable Carbenes". Chem. Rev. 100 (1): 39–91. doi:10.1021/cr940472u. PMID 11749234. (b) Melaimi, M.; Soleilhavoup, M.; Bertrand, G. (2010). "Stable cyclic carbenes and related species beyond diaminocarbenes". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (47): 8810–8849. doi:10.1002/anie.201000165. PMC 3130005. PMID 20836099.

- Grasse, P. B.; Brauer, B. E.; Zupancic, J. J.; Kaufmann, K. J.; Schuster, G. B. (1983). "Chemical and physical properties of fluorenylidene: equilibration of the singlet and triplet carbenes". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 105 (23): 6833. doi:10.1021/ja00361a014.

- Nemirowski, A.; Schreiner, P. R. (November 2007). "Electronic Stabilization of Ground State Triplet Carbenes". J. Org. Chem. 72 (25): 9533–9540. doi:10.1021/jo701615x. PMID 17994760.

- Skell, P. S.; Woodworth, R. C. (1956). "Structure of Carbene, Ch2". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 78 (17): 4496. doi:10.1021/ja01598a087.

- For a concise tutorial on the applications of carbene ligands also beyond diaminocarbenes, see Munz, D (2018). "Pushing Electrons—Which Carbene Ligand for Which Application?". Organometallics. 37 (3): 275–289. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00720.

- For a general review with a focus on applications with diaminocarbenes, see: Hopkinson, M. N.; Richter, C.; Schedler, M.; Glorius, F. (2014). "An overview of N-heterocyclic carbenes". Nature. 510 (7506): 485–496. Bibcode:2014Natur.510..485H. doi:10.1038/nature13384. PMID 24965649. S2CID 672379.

- S. P. Nolan "N-Heterocyclic Carbenes in Synthesis" 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. Print ISBN 9783527314003. Online ISBN 9783527609451. doi:10.1002/9783527609451

- Marion, N.; Diez-Gonzalez, S.; Nolan, S. P. (2007). "N-heterocyclic carbenes as organocatalysts". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46 (17): 2988–3000. doi:10.1002/anie.200603380. PMID 17348057.

- Bajzer, W. X. (2004). "Fluorine Compounds, Organic". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0914201802011026.a01.pub2. ISBN 978-0471238966.

- Yang, Peng; Yang, Wantai (2013-07-10). "Surface Chemoselective Phototransformation of C–H Bonds on Organic Polymeric Materials and Related High-Tech Applications". Chemical Reviews. 113 (7): 5547–5594. doi:10.1021/cr300246p. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 23614481.

- Ping, Jianfeng; Gao, Feng; Chen, Jian Lin; Webster, Richard D.; Steele, Terry W. J. (2015-08-18). "Adhesive curing through low-voltage activation". Nature Communications. 6: 8050. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8050P. doi:10.1038/ncomms9050. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4557340. PMID 26282730.

- Nakashima, Hiroyuki; Hashimoto, Makoto; Sadakane, Yutaka; Tomohiro, Takenori; Hatanaka, Yasumaru (2006-11-01). "Simple and Versatile Method for Tagging Phenyldiazirine Photophores". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (47): 15092–15093. doi:10.1021/ja066479y. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 17117852.

- Blencowe, Anton; Hayes, Wayne (2005-08-05). "Development and application of diazirines in biological and synthetic macromolecular systems". Soft Matter. 1 (3): 178–205. Bibcode:2005SMat....1..178B. doi:10.1039/b501989c. ISSN 1744-6848. PMID 32646075.

- Liu, Michael T. H. (1982-01-01). "The thermolysis and photolysis of diazirines". Chemical Society Reviews. 11 (2): 127. doi:10.1039/cs9821100127. ISSN 1460-4744.

- Elson, Clive M.; Liu, Michael T. H. (1982-01-01). "Electrochemical behaviour of diazirines". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications (7): 415. doi:10.1039/c39820000415. ISSN 0022-4936.

- Buchner, E.; Feldmann, L. (1903). "Diazoessigester und Toluol". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 36 (3): 3509. doi:10.1002/cber.190303603139.

- Staudinger, H.; Kupfer, O. (1912). "Über Reaktionen des Methylens. III. Diazomethan". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 45: 501–509. doi:10.1002/cber.19120450174.

- Von E. Doering, W.; Hoffmann, A. K. (1954). "The Addition of Dichlorocarbene to Olefins". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 76 (23): 6162. doi:10.1021/ja01652a087.

External links

Media related to Carbenes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Carbenes at Wikimedia Commons