Carpal tunnel syndrome

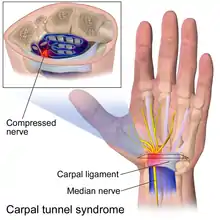

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the collection of symptoms and signs associated with median neuropathy at the carpal tunnel. Most CTS is related to idiopathic compression of the median nerve as it travels through the wrist at the carpal tunnel (IMNCT).[1] Idiopathic means that there is no other disease process contributing to pressure on the nerve. As with most structural issues, it occurs in both hands, and the strongest risk factor is genetics.[1]

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Untreated carpal tunnel syndrome, showing shrinkage (atrophy) of the muscles at the base of the thumb. | |

| Specialty | Orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery |

| Symptoms | Numbness, tingling in the thumb, index, middle finger, and half of ring finger.[1][2] |

| Causes | Compression of the median nerve at the carpal tunnel[1] |

| Risk factors | Genetics, work tasks |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, physical examinations, electrodiagnostic tests[2] |

| Prevention | None |

| Treatment | Wrist splint, corticosteroid injections, surgery[3] |

| Frequency | 5–10%[4][5] |

Other conditions can cause CTS such as wrist fracture or rheumatoid arthritis. After fracture, swelling, bleeding, and deformity compress the median nerve. With rheumatoid arthritis, the enlarged synovial lining of the tendons causes compression.

The main symptoms are numbness and tingling in the thumb, index finger, middle finger and the thumb side of the ring finger.[1] People often report pain, but pain without tingling is not characteristic of IMNCT. Rather, the numbness can be so intense that they are described as painful.

Symptoms are typically most troublesome at night.[2] Untreated, and over years to decades, IMNCT causes loss of sensibility and weakness and shrinkage (atrophy) of the muscles at the base of the thumb.

Work-related factors such as vibration, wrist extension or flexion, hand force, and repetition increase the risk of developing CTS. The only certain risk factor for IMNCT is genetics. All other risk factors are open to debate. It is important to consider IMNCT separately from CTS in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.[6][5][3]

Diagnosis of IMNCT can be made with a high probability based on characteristic symptoms and signs. IMNCT can be measured with electrodiagnostic tests.[7]

People wake less often at night if they wear a wrist splint. Injection of corticosteroids may or may not alleviate better than simulated (placebo) injections.[8][9] There is no evidence that corticosteroid injection alters the natural history of the disease, which seems to be a gradual progression of neuropathy.

Surgery to cut the transverse carpal ligament is the only known disease modifying treatment.[3]

Anatomy

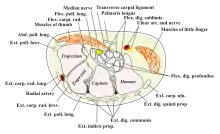

The carpal tunnel is an anatomical compartment located at the base of the palm. Nine flexor tendons and the median nerve pass through the carpal tunnel that is surrounded on three sides by the carpal bones that form an arch. The median nerve provides feeling or sensation to the thumb, index finger, long finger, and half of the ring finger. At the level of the wrist, the median nerve supplies the muscles at the base of the thumb that allow it to abduct, move away from the other four fingers, as well as move out of the plane of the palm. The carpal tunnel is located at the middle third of the base of the palm, bounded by the bony prominence of the scaphoid tubercle and trapezium at the base of the thumb, and the hamate hook that can be palpated along the axis of the ring finger. From the anatomical position, the carpal tunnel is bordered on the anterior surface by the transverse carpal ligament, also known as the flexor retinaculum. The flexor retinaculum is a strong, fibrous band that attaches to the pisiform and the hamulus of the hamate. The proximal boundary is the distal wrist skin crease, and the distal boundary is approximated by a line known as Kaplan's cardinal line.[10] This line uses surface landmarks, and is drawn between the apex of the skin fold between the thumb and index finger to the palpated hamate hook.[11]

Pathophysiology

The median nerve can be compressed by a decrease in the size of the canal, an increase in the size of the contents (such as the swelling of tissue around the flexor tendons), or both.[12] When the pressure builds up inside the tunnel, it damages the median nerve (median neuropathy).

As the median neuropathy gets worse, there is loss of sensibility in the thumb, index, middle, and thumb side of the ring finger. As the neuropathy progresses, there may be first weakness, then to atrophy of the muscles of thenar eminence (the flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and abductor pollicis brevis). The sensibility of the palm remains normal because the superficial sensory branch of the median nerve branches proximal to the TCL and travels superficial to it.[13]

The role of nerve adherence is speculative.[14]

Epidemiology

IMNCT is estimated to affect one out of ten people during their lifetime and is the most common nerve compression syndrome.[5] There is notable variation in such estimates based on how one defines the problem, in particular whether one studies people presenting with symptoms vs. measurable median neuropathy (IMNCT) whether or not people are seeking care. It accounts for about 90% of all nerve compression syndromes.[15] The best data regarding IMNCT and CTS comes from population-based studies, which demonstrate no relationship to gender, and increasing prevalence (accumulation) with age.

Symptoms

The characteristic symptom of CTS is numbness, tingling, or burning sensations in the thumb, index, middle, and radial half of the ring finger. These areas process sensation through the median nerve.[16] Numbness or tingling is usually worse with sleep. People tend to sleep with their wrists flexed, which increases pressure on the nerve. Ache and discomfort may be reported in the forearm or even the upper arm, but its relationship to IMNCT is uncertain.[17] Symptoms that are not characteristic of CTS include pain in the wrists or hands, loss of grip strength,[18] minor loss of sleep,[19] and loss of manual dexterity.[20]

Median nerve symptoms may arise from compression at the level of the thoracic outlet or the area where the median nerve passes between the two heads of the pronator teres in the forearm,[21] although this is debated.

Signs

Severe IMNCT is associated with measurable loss of sensibility. Diminished threshold sensibility (the ability to distinguish different amounts of pressure) can be measured using Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing.[22] Diminished discriminant sensibility can be measured by testing two-point discrimination: the number of millimeters two points of contact need to be separated before you can distinguish them.[23]

A person with idiopathic median neuropathy at the carpal tunnel will not have any sensory loss over the thenar eminence (bulge of muscles in the palm of hand and at the base of the thumb). This is because the palmar branch of the median nerve, which innervates that area of the palm, separates from the median nerve and passes over the carpal tunnel.[24]

Severe IMNCT is also associated with weakness and atrophy of the muscles at the base of the thumb. People may lose the ability to palmarly abduct the thumb. IMNCT can be detected on examination using one of several maneuvers to provoke paresthesia (a sensation of tingling or "pins and needles" in the median nerve distribution). These so-called provocative signs include:

- Phalen's maneuver. Performed by fully flexing the wrist, then holding this position and awaiting symptoms.[25] A positive test is one that results in paresthesia in the median nerve distribution within sixty seconds.

- Tinel's sign is performed by lightly tapping the median nerve just proximal to flexor retinaculum to elicit paresthesia.[5]

- Durkan test, carpal compression test, or applying firm pressure to the palm over the nerve for up to 30 seconds to elicit paresthesia.[26][27]

- Hand elevation test The hand elevation test is performed by lifting both hands above the head. Paresthesia in the median nerve distribution within 2 minutes is considered positive.

Diagnostic performance characteristics such as sensitivity and specificity are reported, but difficult to interpret because of the lack of a consensus reference standard for CTS or IMNCT.

Causes

Idiopathic Median Neuropathy at the Carpal Tunnel

Genetic factors are believed to be the most important determinants of who develops carpal tunnel syndrome due to IMNCT. In other words, your wrist structure seems programmed at birth to develop IMNCT later in life. A genome-wide association study (GWAS) of carpal tunnel syndrome identified 16 genomic loci significantly associated with the disease, including several loci previously known to be associated with human height.[28]

Factors that may contribute to symptoms, but have not been experimentally associated with neuropathy include obesity, and Diabetes mellitus .[3][29][30] One case-control study noted that individuals classified as obese (BMI > 29) are 2.5 times more likely than slender individuals (BMI < 20) to be diagnosed with CTS.[31] It's not clear whether this association is due to an alteration of pathophysiology, a variation in symptoms, or a variation in care-seeking.[32]

Discrete Pathophysiology and Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Hereditary neuropathy with susceptibility to pressure palsies is a genetic condition that appears to increase the probability of developing MNCT. Heterozygous mutations in the gene SH3TC2, associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth, may confer susceptibility to neuropathy, including CTS.[33]

Association between common benign tumors such as lipomas, ganglion, and vascular malformation should be handled with care. Such tumors are very common and overlap with IMNCT is more likely than pressure on the median nerve.[34] Similarly, the degree to which transthyretin amyloidosis-associated polyneuropathy and carpal tunnel syndrome is under investigation. Prior carpal tunnel release is often noted in individuals who later present with transthyretin amyloid-associated cardiomyopathy.[35] There is consideration that bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome could be a reason to consider amyloidosis, timely diagnosis of which could improve heart health.[36] Amyloidosis is rare, even among people with carpal tunnel syndrome (0.55% incidence within 10 years of carpal tunnel release).[37] In the absence of other factors associated with a notable probability of amyloidosis, it's not clear that biopsy at the time of carpal tunnel release has a suitable balance between potential harms and potential benefits.[37]

Other specific pathophysiologies that can cause median neuropathy via pressure include:

- Rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases that cause inflammation of the flexor tendons.

- With severe untreated hypothyroidism, generalized myxedema causes deposition of mucopolysaccharides within both the perineurium of the median nerve, as well as the tendons passing through the carpal tunnel. Association of CTS and IMNCT with lesser degrees of hypothyroidism is questioned.

- Pregnancy may bring out symptoms in genetically predisposed individuals. Perhaps the changes in hormones and fluid increase pressure temporarily in the carpal tunnel.[32] High progesterone levels and water retention may increase the size of the synovium.

- Bleeding and swelling from a fracture or dislocation. This is referred to as acute carpal tunnel syndrome.[38]

- Acromegaly causes excessive secretion of growth hormones. This causes the soft tissues and bones around the carpal tunnel to grow and compress the median nerve.[39]

Other considerations

- Double-crush syndrome is a debated hypothesis that compression or irritation of nerve branches contributing to the median nerve in the neck, or anywhere above the wrist, increases sensitivity of the nerve to compression in the wrist. There is little evidence to support this theory and some concern that it may be used to justify more surgery.[40][41]

Median Neuropathy and Activity

Work-related factors that increase risk of CTS include vibration (5.4 effect ratio), hand force (4.2), and repetition (2.3). Exposure to wrist extension or flexion at work increases the risk of CTS by two times. The balance of evidence suggests that keyboard and computer use does not cause CTS.[42]

The international debate regarding the relationship between CTS and repetitive hand use (at work in particular) is ongoing. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has adopted rules and regulations regarding so-called "cumulative trauma disorders" based concerns regarding potential harm from exposure to repetitive tasks, force, posture, and vibration.[43][44]

A review of available scientific data by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) indicated that job tasks that involve highly repetitive manual acts or specific wrist postures were associated with symptoms of CTS, but there was not a clear distinction of paresthesia (appropriate) from pain (inappropriate) and causation was not established. The distinction from work-related arm pains that are not carpal tunnel syndrome was unclear. It is proposed that repetitive use of the arm can affect the biomechanics of the upper limb or cause damage to tissues. It is proposed that postural and spinal assessment along with ergonomic assessments should be considered, based on observation that addressing these factors has been found to improve comfort in some studies although experimental data are lacking and the perceived benefits may not be specific to those interventions.[45][46] A 2010 survey by NIOSH showed that 2/3 of the 5 million carpal tunnel diagnosed in the US that year were related to work.[47] Women are more likely to be diagnosed with work-related carpal tunnel syndrome than men.[48]

Associated conditions

A variety of patient factors can lead to CTS, including heredity, size of the carpal tunnel, associated local and systematic diseases, and certain habits.[49] Non-traumatic causes generally happen over a period of time, and are not triggered by one certain event. Many of these factors are manifestations of physiologic aging.[50]

Diagnosis

There is no consensus reference standard for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. A combination of characteristic symptoms (how it feels) and signs (what the clinician finds on exam) are associated with a high probability of IMNCT without electrophysiological testing.

Electrodiagnostic testing (electromyography and nerve conduction velocity) can objectively measure and verify median neuropathy.[51]

Ultrasound can image and measure the cross sectional diameter of the median nerve, which has some correlation with idiopathic median neuropathy at the carpal tunnel (IMNCT). The role of ultrasound in diagnosis--just as for electrodiagnostic testing--is a matter of debate. EDX cannot fully exclude the diagnosis of CTS due to the lack of sensitivity. A joint report published by the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM), the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R), and the American Academy of Neurology defines practice parameters, standards, and guidelines for EDX studies of CTS based on an extensive critical literature review. This joint review concluded median and sensory nerve conduction studies are valid and reproducible in a clinical laboratory setting and a clinical diagnosis of CTS can be made with a sensitivity greater than 85% and specificity greater than 95%. Given the key role of electrodiagnostic testing in the diagnosis of CTS, The AANEM has issued evidence-based practice guidelines, both for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Electrodiagnostic testing (electromyography and nerve conduction velocity) can objectively verify the median nerve dysfunction. Normal nerve conduction studies, however, do not exclude the diagnosis of CTS. Clinical assessment by history taking and physical examination can support a diagnosis of CTS. If clinical suspicion of CTS is high, treatment should be initiated despite normal electrodiagnostic testing.

The role of confirmatory electrodiagnostic testing is debated.[5] The goal of electrodiagnostic testing is to compare the speed of conduction in the median nerve with conduction in other nerves supplying the hand. When the median nerve is compressed, as in IMNCT, it will conduct more slowly than normal and more slowly than other nerves. Compression results in damage to the myelin sheath and manifests as delayed latencies and slowed conduction velocities.[49] There are many electrodiagnostic tests used to make a diagnosis of CTS, but the most sensitive, specific, and reliable test is the Combined Sensory Index (also known as the Robinson index).[52] Electrodiagnosis rests upon demonstrating impaired median nerve conduction across the carpal tunnel in context of normal conduction elsewhere. It is often stated that normal electrodiagnostic studies do not preclude the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. The rational for this is that a threshold of neuropathy must be reached before study results become abnormal and also that threshold values for abnormality vary.[53] Others contend that idiopathic median neuropathy at the carpal tunnel with normal electrodiagnostic tests would represent very, very mild neuropathy that would be best managed as a normal median nerve. Even more important, notable symptoms with mild disease is strongly associated with unhelpful thoughts and symptoms of worry and despair. Notable CTS with unmeasurable IMNCT should remind clinicians to always consider the whole person, including their mindset and circumstances, in strategies to help people get and stay healthy.[54]

Imaging

The role of MRI or ultrasound imaging in the diagnosis of idiopathic median neuropathy at the carpal tunnel (IMNCT) is unclear.[55][56][57] Their routine use is not recommended.[3] MRI has high sensitivity but low specificity for IMNCT. High signal intensity may suggest accumulation of axonal transportation, myelin sheath degeneration or oedema.[58]

Differential diagnosis

There are few disorders on the differential diagnosis for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cervical radiculopathy can also cause paresthesia abnormal sensibility in the hands and wrist.[5] The distribution usually follows the nerve root, and the paresthesia may be provoked by neck movement.[5] Electromyography and imaging of the cervical spine can help to differentiate cervical radiculopathy from carpal tunnel syndrome if the diagnosis is unclear.[5] Carpal tunnel syndrome is sometimes applied as a label to anyone with pain, numbness, swelling, or burning in the radial side of the hands or wrists. When pain is the primary symptom, carpal tunnel syndrome is unlikely to be the source of the symptoms.[59]

When the symptoms and signs point to atrophy and muscle weakness more than numbness, consider neurodegenerative disorders such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis or Charcot-Marie Tooth.[60][61][62]

Prevention

There is little or no data to support the concept that activity adjustment prevents carpal tunnel syndrome.[63] The evidence for wrist rest is debated.[64] There is also little research supporting that ergonomics is related to carpal tunnel syndrome.[65] Due to risk factors for hand and wrist dysfunction being multifactorial and very complex it is difficult to assess the true physical factors of carpal tunnel syndrome.[66]

Biological factors such as genetic predisposition and anthropometric features are more strongly associated with idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome than occupational/environmental factors such as hand use.[63]

Treatment

Generally accepted treatments include: physiotherapy, steroids either orally or injected locally, splinting, and surgical release of the transverse carpal ligament.[67] Limited evidence suggests that gabapentin is no more effective than placebo for CTS treatment.[5] There is insufficient evidence to recommend therapeutic ultrasound, yoga, acupuncture, low level laser therapy, vitamin B6, myofascial release, and any form of stretch or exercise.[5][67] Change in activity may include avoiding activities that worsen symptoms.[68]

The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons recommends proceeding conservatively with a course of nonsurgical therapies tried before release surgery is considered.[69] A different treatment should be tried if the current treatment fails to resolve the symptoms within 2 to 7 weeks. Early surgery with carpal tunnel release is indicated where there is evidence of median nerve denervation or a person elects to proceed directly to surgical treatment.[69] Recommendations may differ when carpal tunnel syndrome is found in association with the following conditions: diabetes mellitus, coexistent cervical radiculopathy, hypothyroidism, polyneuropathy, pregnancy, rheumatoid arthritis, and carpal tunnel syndrome in the workplace.[69]

Splint Immobilizations

The importance of wrist braces and splints in the carpal tunnel syndrome therapy is known, but many people are unwilling to use braces. In 1993, The American Academy of Neurology recommended a non-invasive treatment for the CTS at the beginning (except for sensitive or motor deficit or grave report at EMG/ENG): a therapy using splints was indicated for light and moderate pathology.[70] Current recommendations generally don't suggest immobilizing braces, but instead activity modification and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as initial therapy, followed by more aggressive options or specialist referral if symptoms do not improve.[71][72]

Many health professionals suggest that, for the best results, one should wear braces at night. When possible, braces can be worn during the activity primarily causing stress on the wrists.[73][74] The brace should not generally be used during the day as wrist activity is needed to keep the wrist from becoming stiff and to prevent muscles from weakening.[75]

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid injections may provide temporary alleviation of symptoms although they are not clearly better than placebo.[76] This form of treatment is thought to reduce discomfort in those with CTS due to its ability to decrease median nerve swelling.[5] The use of ultrasound while performing the injection is more expensive but leads to faster resolution of CTS symptoms.[5] The injections are done under local anesthesia.[77][78] This treatment is not appropriate for extended periods, however. In general, local steroid injections are only used until more definitive treatment options can be used. Corticosteroid injections do not appear to slow disease progression.[5]

Surgery

Release of the transverse carpal ligament is known as "carpal tunnel release" surgery. It is recommended when there is static (constant, not just intermittent) numbness, muscle weakness, or atrophy, and when night-splinting or other palliative interventions no longer alleviate intermittent symptoms.[79] The surgery may be done with local[80][81][82] or regional anesthesia[83] with[84] or without[81] sedation, or under general anesthesia.[82][83] In general, milder cases can be controlled for months to years, but severe cases are unrelenting symptomatically and are likely to result in surgical treatment.[85]

Surgery is more beneficial in the short term to alleviate symptoms (up to six months) than wearing an orthosis for a minimum of six weeks. However, surgery and wearing a brace resulted in similar symptom relief in the long term (12–18 month outcomes).[86]

Physical therapy

An evidence-based guideline produced by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons assigned various grades of recommendation to physical therapy and other nonsurgical treatments.[87] One of the primary issues with physiotherapy is that it attempts to reverse (often) years of pathology inside the carpal tunnel. Self-myofascial ligament stretching can be an easy, do-at-home, treatment to help alleviate symptoms. Self-myofascial stretching involves stretching the carpal ligament for 30 seconds, 6 times a day for about 6 weeks. Many patients report improvements in symptoms such as pain, function, and nerve conduction.[88] Practitioners caution that any physiotherapy such as myofascial release may take weeks of persistent application to effectively manage carpal tunnel syndrome.[89]

Again, some claim that pro-active ways to reduce stress on the wrists, which alleviates wrist pain and strain, involve adopting a more ergonomic work and life environment. For example, some have claimed that switching from a QWERTY computer keyboard layout to a more optimised ergonomic layout such as Dvorak was commonly cited as beneficial in early CTS studies; however, some meta-analyses of these studies claim that the evidence that they present is limited.[90][91]

Tendon and nerve gliding exercises appear to be useful in carpal tunnel syndrome.[92]

A randomized control trial published in 2017 sought to examine the efficacy of manual therapy techniques for the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. The study included a total of 140 individuals diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome and the patients were divided into two groups. One group received treatment that consisted of manual therapy. Manual therapy included the incorporation of specified neurodynamic techniques, functional massage, and carpal bone mobilizations. Another group only received treatment through electrophysical modalities. The duration of the study was over the course of 20 physical therapy sessions for both groups. Results of this study showed that the group being treated through manual techniques and mobilizations yielded a 290% reduction in overall pain when compared to reports of pain prior to conducting the study. Total function improved by 47%. Conversely, the group being treated with electrophysical modalities reported a 47% reduction in overall pain with a 9% increase in function.[93]

Alternative medicine

A 2018 Cochrane review on acupuncture and related interventions for the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome concluded that, "Acupuncture and laser acupuncture may have little or no effect in the short term on symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) in comparison with placebo or sham acupuncture." It was also noted that all studies had an unclear or high overall risk of bias and that all evidence was of low or very low quality.[94]

Prognosis

Most people relieved of their carpal tunnel symptoms with conservative or surgical management find minimal residual or "nerve damage".[95] Long-term chronic carpal tunnel syndrome (typically seen in the elderly) can result in permanent "nerve damage", i.e. irreversible numbness, muscle wasting, and weakness. Those that undergo a carpal tunnel release are nearly twice as likely as those not having surgery to develop trigger thumb in the months following the procedure.[96]

While outcomes are generally good, certain factors can contribute to poorer results that have little to do with nerves, anatomy, or surgery type. One study showed that mental status parameters or alcohol use yields much poorer overall results of treatment.[97]

Recurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome after successful surgery is rare.[98][99]

History

The condition known as carpal tunnel syndrome had major appearances throughout the years but it was most commonly heard of in the years following World War II.[100] Individuals who had had this condition have been depicted in surgical literature for the mid-19th century.[100] In 1854, Sir James Paget was the first to report median nerve compression at the wrist in two cases.[101][102]

The first to notice the association between the carpal ligament pathology and median nerve compression appear to have been Pierre Marie and Charles Foix in 1913.[103] They described the results of a postmortem of an 80-year-old man with bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. They suggested that division of the carpal ligament would be curative in such cases. Putman had previously described a series of 37 patients and suggested a vasomotor origin.[104] The association between the thenar muscle atrophy and compression was noted in 1914.[105] The name "carpal tunnel syndrome" appears to have been coined by Moersch in 1938.[106]

In the early 20th century there were various cases of median nerve compression underneath the transverse carpal ligament.[102] Physician George S. Phalen of the Cleveland Clinic identified the pathology after working with a group of patients in the 1950s and 1960s.[107][108]

- Treatment

Paget described two cases of carpal tunnel syndrome. The first was due to an injury where a cord had been wrapped around a man's wrist. The second was due to a distal radial fracture. For the first case, Paget performed an amputation of the hand. For the second case Paget recommended a wrist splint – a treatment that is still in use today. Surgery for this condition initially involved the removal of cervical ribs despite Marie and Foix's suggested treatment. In 1933 Sir James Learmonth outlined a method of decompression of the nerve at the wrist.[109] This procedure appears to have been pioneered by the Canadian surgeons Herbert Galloway and Andrew MacKinnon in 1924 in Winnipeg but was not published.[110] Endoscopic release was described in 1988.[111]

See also

- Repetitive strain injury

- Tarsal tunnel syndrome

- Ulnar nerve entrapment

References

- Burton, C; Chesterton, LS; Davenport, G (May 2014). "Diagnosing and managing carpal tunnel syndrome in primary care". The British Journal of General Practice. 64 (622): 262–3. doi:10.3399/bjgp14x679903. PMC 4001168. PMID 24771836.

- "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. January 28, 2016. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (February 29, 2016). "Management of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline". Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- Bickel, KD (January 2010). "Carpal tunnel syndrome". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 35 (1): 147–52. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.11.003. PMID 20117319.

- Padua, L; Coraci, D; Erra, C; Pazzaglia, C; Paolasso, I; Loreti, C; Caliandro, P; Hobson-Webb, LD (November 2016). "Carpal tunnel syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, and management". Lancet Neurology (Review). 15 (12): 1273–84. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30231-9. PMID 27751557. S2CID 9991471.

- Shiri, R (December 2014). "Hypothyroidism and carpal tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis". Muscle & Nerve. 50 (6): 879–83. doi:10.1002/mus.24453. PMID 25204641. S2CID 37496158.

- Graham, Brent (December 2008). "The Value Added by Electrodiagnostic Testing in the Diagnosis of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American Volume. 90 (12): 2587–2593. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.01362. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 19047703.

- Boyer, Martin I. (October 2008). "Corticosteroid Injection for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 33 (8): 1414–1416. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.06.023. PMID 18929212.

- Huisstede, Bionka M.; Randsdorp, Manon S.; van den Brink, Janneke; Franke, Thierry P.C.; Koes, Bart W.; Hoogvliet, Peter (August 2018). "Effectiveness of Oral Pain Medication and Corticosteroid Injections for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Systematic Review". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 99 (8): 1609–1622.e10. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2018.03.003. PMID 29626428. S2CID 4683880.

- Brooks, JJ; Schiller, JR; Allen, SD; Akelman, E (Oct 2003). "Biomechanical and anatomical consequences of carpal tunnel release". Clinical Biomechanics (Bristol, Avon). 18 (8): 685–93. doi:10.1016/S0268-0033(03)00052-4. PMID 12957554.

- Vella, JC; Hartigan, BJ; Stern, PJ (Jul–Aug 2006). "Kaplan's cardinal line". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 31 (6): 912–8. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.03.009. PMID 16843150.

- RH Gelberman; PT Hergenroeder; AR Hargens; GN Lundborg; WH Akeson (1 March 1981). "The carpal tunnel syndrome. A study of carpal canal pressures". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 63 (3): 380–383. doi:10.2106/00004623-198163030-00009. PMID 7204435. Archived from the original on 22 March 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- Norvell, Jeffrey G.; Steele, Mark (September 10, 2009). "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". eMedicine. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010.

- Armstrong T., Chaffin D. (1979). "Capral tunnel syndrome and selected personal attributes". Journal of Occupational Medicine. 21 (7).

- Ibrahim I.; Khan W. S.; Goddard N.; Smitham P. (2012). "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Review of the Recent Literature". The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 6: 69–76. doi:10.2174/1874325001206010069. PMC 3314870. PMID 22470412.

- Aroori, Somalah; AJ Spence, Roy (2008). "Carpal tunnel syndrome". Ulster Medical Journal. 77 (1): 6–17. PMC 2397020. PMID 18269111.

- "Carpal tunnel syndrome – Symptoms". NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 2016-05-24. Retrieved 2016-05-21. Page last reviewed: 18/09/2014

- Atroshi, I.; Gummesson, C; Johnsson, R; Ornstein, E; Ranstam, J; Rosén, I (1999). "Prevalence of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in a General Population". JAMA. 282 (2): 153–158. doi:10.1001/jama.282.2.153. PMID 10411196.

- Boyko, Tatiana (January 24, 2022). "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". TXOSA. Archived from the original on 2022-01-24.

- "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. December 28, 2010. Archived from the original on December 22, 2010.

- Netter, Frank (2011). Atlas of Human Anatomy (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 412, 417, 435. ISBN 978-0-8089-2423-4.

- Szabo, R M; Gelberman, R H; Dimick, M P (January 1984). "Sensibility testing in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome". The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 66 (1): 60–64. doi:10.2106/00004623-198466010-00009. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 6690444.

- Elfar, John C.; Yaseen, Zaneb; Stern, Peter J.; Kiefhaber, Thomas R. (November 2010). "Individual Finger Sensibility in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 35 (11): 1807–1812. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.08.013. PMC 4410266. PMID 21050964.

- Netter, Frank (2011). Atlas of Human Anatomy (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-8089-2423-4.

- Cush JJ, Lipsky PE (2004). "Approach to articular and musculoskeletal disorders". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 2035. ISBN 978-0-07-140235-4.

- Gonzalezdelpino, J; Delgadomartinez, A; Gonzalezgonzalez, I; Lovic, A (1997). "Value of the carpal compression test in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 22 (1): 38–41. doi:10.1016/S0266-7681(97)80012-5. PMID 9061521. S2CID 25924364.

- Durkan, JA (1991). "A new diagnostic test for carpal tunnel syndrome". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 73 (4): 535–8. doi:10.2106/00004623-199173040-00009. PMID 1796937. S2CID 11545887.

- Wiberg, A (4 March 2019). "A genome-wide association analysis identifies 16 novel susceptibility loci for carpal tunnel syndrome". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1030. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1030W. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08993-6. PMC 6399342. PMID 30833571.

- Osterman, M; Ilyas, AM; Matzon, JL (October 2012). "Carpal tunnel syndrome in pregnancy". The Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 43 (4): 515–20. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2012.07.020. PMID 23026467.

- Lozano-Calderón, S; Anthony, S; Ring, D (April 2008). "The quality and strength of evidence for etiology: example of carpal tunnel syndrome". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 33 (4): 525–38. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.01.004. PMID 18406957.

- Werner, Robert A.; Albers, James W.; Franzblau, Alfred; Armstrong, Thomas J. (1994). "The relationship between body mass index and the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome". Muscle & Nerve. 17 (6): 632–6. doi:10.1002/mus.880170610. hdl:2027.42/50161. PMID 8196706. S2CID 16722546.

- Padua, Luca; Coraci, Daniele; Erra, Carmen; Pazzaglia, Costanza; Paolasso, Ilaria; Loreti, Claudia; Caliandro, Pietro; Hobson-Webb, Lisa D (November 2016). "Carpal tunnel syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, and management". The Lancet Neurology. 15 (12): 1273–1284. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30231-9. PMID 27751557. S2CID 9991471.

- Lupski, James R.; Reid, Jeffrey G.; Gonzaga-Jauregui, Claudia; Rio Deiros, David; Chen, David C.Y.; Nazareth, Lynne; Bainbridge, Matthew; Dinh, Huyen; et al. (2010). "Whole-Genome Sequencing in a Patient with Charcot–Marie–Tooth Neuropathy". New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (13): 1181–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0908094. PMC 4036802. PMID 20220177.

- Tiong, W. H. C.; Ismael, T.; Regan, P. J. (2005). "Two rare causes of carpal tunnel syndrome". Irish Journal of Medical Science. 174 (3): 70–8. doi:10.1007/BF03170208. PMID 16285343. S2CID 71606479.

- Conceição, I; González-Duarte, A; Obici, L; Schmidt, HH; Simoneau, D; Ong, ML; Amass, L (March 2016). ""Red-flag" symptom clusters in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy". Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System. 21 (1): 5–9. doi:10.1111/jns.12153. PMC 4788142. PMID 26663427.

- Donnelly, Joseph P.; Hanna, Mazen; Sperry, Brett W.; Seitz, William H. (October 2019). "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Potential Early, Red-Flag Sign of Amyloidosis". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 44 (10): 868–876. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2019.06.016. PMID 31400950. S2CID 199540407.

- Sood, Ravi F.; Kamenko, Srdjan; McCreary, Eleanor; Sather, Bergen K.; Schmitt, Michael; Peterson, Steven L.; Lipira, Angelo B. (2021-07-21). "Diagnosing Systemic Amyloidosis Presenting as Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Risk Nomogram to Guide Biopsy at Time of Carpal Tunnel Release". Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 103 (14): 1284–1294. doi:10.2106/JBJS.20.02093. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 34097669. S2CID 235370526.

- Dyer, George; Lozano-Calderon, Santiago; Gannon, Caitlin; Baratz, Mark; Ring, David (October 2008). "Predictors of Acute Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Associated With Fracture of the Distal Radius". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 33 (8): 1309–1313. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.04.012. PMID 18929193.

- "Carpel Tunnel Syndrome in Acromegaly". Treatmentandsymptoms.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- Molinari, William J.; Elfar, John C. (Apr 2014). "The Double Crush Syndrome". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 38 (4): 799–801. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.12.038. ISSN 0363-5023. PMC 5823245. PMID 23466128.

- Kane, Patrick M.; Daniels, Alan H.; Akelman, Edward (Sep 2015). "Double Crush Syndrome". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 23 (9): 558–562. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00176. ISSN 1940-5480. PMID 26306807. S2CID 207531472.

- Newington, L; Harris, EC; Walker-Bone, K (June 2015). "Carpal tunnel syndrome and work". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 29 (3): 440–53. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.026. PMC 4759938. PMID 26612240.

- Derebery, J (2006). "Work-related carpal tunnel syndrome: the facts and the myths". Clinics in Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 5 (2): 353–67, viii. doi:10.1016/j.coem.2005.11.014 (inactive 31 July 2022). PMID 16647653.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022 (link) - Office of Communications and Public Liaison (December 18, 2009). "National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- Cole, Donald C.; Hogg-Johnson, Sheilah; Manno, Michael; Ibrahim, Selahadin; Wells, Richard P.; Ferrier, Sue E.; Worksite Upper Extremity Research Group (2006). "Reducing musculoskeletal burden through ergonomic program implementation in a large newspaper". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 80 (2): 98–108. doi:10.1007/s00420-006-0107-6. PMID 16736193. S2CID 21845851.

- O'Connor, Denise; Page, Matthew J; Marshall, Shawn C; Massy‐Westropp, Nicola (2012-01-18). "Ergonomic positioning or equipment for treating carpal tunnel syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (1): CD009600. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009600. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6486220. PMID 22259003.

- Luckhaupt, Sara E.; Burris, Dara L. (24 June 2013). "How Does Work Affect the Health of the U.S. Population? Free Data from the 2010 NHIS-OHS Provides the Answers". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Swanson, Naomi; Tisdale-Pardi, Julie; MacDonald, Leslie; Tiesman, Hope M. (13 May 2013). "Women's Health at Work". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Scott, Kevin R.; Kothari, Milind J. (October 5, 2009). "Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome". UpToDate.

- Stevens JC, Beard CM, O'Fallon WM, Kurland LT (1992). "Conditions associated with carpal tunnel syndrome". Mayo Clin Proc. 67 (6): 541–548. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(12)60461-3. PMID 1434881.

- Rosario, Neal Bryan; De Jesus, Orlando (2022), "Electrodiagnostic Evaluation Of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32965906, retrieved 2022-07-28

- Robinson, L (2007). "Electrodiagnosis of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 18 (4): 733–46. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2007.07.008. PMID 17967362.

- Graham, B; Regehr G; Naglie G; Wright JG (2006). "Development and validation of diagnostic criteria for carpal tunnel syndrome". Journal of Hand Surgery. 31A (6): 919–924. PMID 16886290.

- Crum, Alia, and Barry Zuckerman. “Changing Mindsets to Enhance Treatment Effectiveness.” JAMA vol. 317,20 (2017): 2063–2064. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.4545

- Wilder-Smith, Einar P; Seet, Raymond C S; Lim, Erle C H (2006). "Diagnosing carpal tunnel syndrome—clinical criteria and ancillary tests". Nature Clinical Practice Neurology. 2 (7): 366–74. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0216. PMID 16932587. S2CID 22566215.

- Bland, Jeremy DP (2005). "Carpal tunnel syndrome". Current Opinion in Neurology. 18 (5): 581–5. doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000173142.58068.5a. PMID 16155444. S2CID 945614.

- Jarvik, J; Yuen, E; Kliot, M (2004). "Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: electrodiagnostic and MR imaging evaluation". Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 14 (1): 93–102, viii. doi:10.1016/j.nic.2004.02.002. PMID 15177259.

- Zamborsky, Radoslav; Kokavec, Milan; Simko, Lukas; Bohac, Martin (2017-01-26). "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Symptoms, Causes and Treatment Options. Literature Reviev". Ortopedia, Traumatologia, Rehabilitacja. 19 (1): 1–8. doi:10.5604/15093492.1232629. ISSN 2084-4336. PMID 28436376.

- Graham, B. (1 December 2008). "The Value Added by Electrodiagnostic Testing in the Diagnosis of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 90 (12): 2587–2593. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.01362. PMID 19047703.

- Genova, Alessia; Dix, Olivia; Saefan, Asem; Thakur, Mala; Hassan, Abbas (2020). "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Review of Literature". Cureus. 12 (3): e7333. doi:10.7759/cureus.7333. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 7164699. PMID 32313774.

- Masrori, P.; Van Damme, P. (October 2020). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a clinical review". European Journal of Neurology. 27 (10): 1918–1929. doi:10.1111/ene.14393. ISSN 1351-5101. PMC 7540334. PMID 32526057.

- Nagappa, Madhu; Sharma, Shivani; Taly, Arun B. (2022), "Charcot Marie Tooth", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32965834, retrieved 2022-09-06

- Lozano-Calderón, Santiago; Shawn Anthony; David Ring (April 2008). "The Quality and Strength of Evidence for Etiology: Example of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 33 (4): 525–538. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.01.004. PMID 18406957.

- "Wrist Rests : OSH Answers". Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety. Archived from the original on 2017-04-15. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- Goodman, G (2014-12-08). Ergonomic interventions for computer users with cumulative trauma disorders. International handbook of occupational therapy interventions. 2nd ed. pp. 205–17. ISBN 978-3-319-08140-3.

- Kalliainen, Loree K. (2017). "Nonoperative Options for the Management of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Related Median Neuropathies. Springer, Cham. pp. 109–124. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-57010-5_11. ISBN 978-3-319-57008-2.

- Piazzini, DB; Aprile, I; Ferrara, PE; Bertolini, C; Tonali, P; Maggi, L; Rabini, A; Piantelli, S; Padua, L (Apr 2007). "A systematic review of conservative treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome". Clinical Rehabilitation. 21 (4): 299–314. doi:10.1177/0269215507077294. PMID 17613571. S2CID 39628211.

- "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. December 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- Clinical Practice Guideline on the Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (PDF). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. September 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-11. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- American Academy of Neurology (2006). "Quality Standards Subcommittee: Practice parameter for carpal tunnel syndrome". Neurology. 43 (11): 2406–2409. doi:10.1212/wnl.43.11.2406. PMID 8232968. S2CID 21438072.

- Katz, Jeffrey N.; Simmons, Barry P. (2002). "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 346 (23): 1807–1812. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp013018. PMID 12050342. S2CID 27783521.

- Harris JS, ed. (1998). Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines: evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers. Beverly Farms, Mass.: OEM Press. ISBN 978-1-883595-26-5.

- Premoselli, S; Sioli, P; Grossi, A; Cerri, C (2006). "Neutral wrist splinting in carpal tunnel syndrome: a 3- and 6-months clinical and neurophysiologic follow-up evaluation of night-only splint therapy". Europa Medicophysica. 42 (2): 121–6. PMID 16767058.

- Michlovitz, SL (2004). "Conservative interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome". The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 34 (10): 589–600. doi:10.2519/jospt.2004.34.10.589. PMID 15552705.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (November 16, 2017). Carpal tunnel syndrome: Wrist splints and hand exercises. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG).

- Marshall, Shawn C; Tardif, Gaetan; Ashworth, Nigel L; Marshall, Shawn C (2007). Marshall, Shawn C (ed.). "Local corticosteroid injection for carpal tunnel syndrome". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001554. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001554.pub2. PMID 17443508.

- "Carpal Tunnel Steroid Injection". Medscape. Archived from the original on July 29, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- "Carpal Tunnel Injection Information". EBSCO. Archived from the original on 2015-07-10 – via The Mount Sinai Hospital.

- Hui, A.C.F.; Wong, S.M.; Tang, A.; Mok, V.; Hung, L.K.; Wong, K.S. (2004). "Long-term outcome of carpal tunnel syndrome after conservative treatment". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 58 (4): 337–9. doi:10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.00028.x. PMID 15161116. S2CID 12545439.

- "Open Carpal Tunnel Surgery for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". WebMD. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- al Youha, Sarah; Lalonde, Donald (May 2014). "Update/Review: Changing of Use of Local Anesthesia in the Hand". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open. 2 (5): e150. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000000095. PMC 4174079. PMID 25289343.

- Nabhan A, Ishak B, Al-Khayat J, Steudel W-I (April 25, 2008). "Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release using a modified application technique of local anesthesia: safety and effectiveness". Journal of Brachial Plexus and Peripheral Nerve Injury. 3 (11): e35–e38. doi:10.1186/1749-7221-3-11. PMC 2383895. PMID 18439257.

- "AAOS Informed Patient Tutorial – Carpal Tunnel Release Surgery". The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Archived from the original on July 19, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Lee J-J, Hwang SM, Jang JS, Lim SY, Heo D-H, Cho YJ (2010). "Remifentanil-Propofol Sedation as an Ambulatory Anesthesia for Carpal Tunnel Release". Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 48 (5): 429–433. doi:10.3340/jkns.2010.48.5.429. PMC 3030083. PMID 21286480.

- Kouyoumdjian, JA; Morita, MP; Molina, AF; Zanetta, DM; Sato, AK; Rocha, CE; Fasanella, CC (2003). "Long-term outcomes of symptomatic electrodiagnosed carpal tunnel syndrome". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 61 (2A): 194–8. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2003000200007. PMID 12806496.

- D'Angelo, Kevin; Sutton, Deborah; Côté, Pierre; Dion, Sarah; Wong, Jessica J.; Yu, Hainan; Randhawa, Kristi; Southerst, Danielle; Varatharajan, Sharanya (2015). "The Effectiveness of Passive Physical Modalities for the Management of Soft Tissue Injuries and Neuropathies of the Wrist and Hand: A Systematic Review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration". Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 38 (7): 493–506. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.06.006. PMID 26303967.

- Keith, M. W.; Masear, V.; Chung, K. C.; Amadio, P. C.; Andary, M.; Barth, R. W.; Maupin, K.; Graham, B.; Watters, W. C.; Turkelson, C. M.; Haralson, R. H.; Wies, J. L.; McGowan, R. (4 January 2010). "American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline on The Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 92 (1): 218–219. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00642. PMC 6882524. PMID 20048116. S2CID 7604145.

- Jiménez-del-Barrio, Sandra; Cadellans-Arróniz, Aida; Ceballos-Laita, Luis; Estébanez-de-Miguel, Elena; López-de-Celis, Carles; Bueno-Gracia, Elena; Pérez-Bellmunt, Albert (February 2022). "The effectiveness of manual therapy on pain, physical function, and nerve conduction studies in carpal tunnel syndrome patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis". International Orthopaedics. 46 (2): 301–312. doi:10.1007/s00264-021-05272-2. ISSN 0341-2695. PMC 8782801. PMID 34862562.

- Siu, G.; Jaffee, J.D.; Rafique, M.; Weinik, M.M. (1 March 2012). "Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 112 (3): 127–139. PMID 22411967.

- Lincoln, A; Vernick, JS; Ogaitis, S; Smith, GS; Mitchell, CS; Agnew, J (2000). "Interventions for the primary prevention of work-related carpal tunnel syndrome". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 18 (4 Suppl): 37–50. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00140-9. PMID 10793280.

- Verhagen, Arianne P; Karels, Celinde C; Bierma-Zeinstra, Sita MA; Burdorf, Lex L; Feleus, Anita; Dahaghin, Saede SD; De Vet, Henrica CW; Koes, Bart W; Verhagen, Arianne P (2006). Verhagen, Arianne P (ed.). "Ergonomic and physiotherapeutic interventions for treating work-related complaints of the arm, neck or shoulder in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD003471. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003471.pub3. PMID 16856010. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003471.pub4)

- Kim, SD (August 2015). "Efficacy of tendon and nerve gliding exercises for carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 27 (8): 2645–8. doi:10.1589/jpts.27.2645. PMC 4563334. PMID 26357452.

- Wolny, Tomasz; Saulicz, Edward; Linek, Paweł; Shacklock, Michael; Myśliwiec, Andrzej (May 2017). "Efficacy of Manual Therapy Including Neurodynamic Techniques for the Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 40 (4): 263–272. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.02.004. ISSN 1532-6586. PMID 28395984. S2CID 4132062.

- Choi GH, Wieland LS, Lee H, Sim H, Lee MS, Shin BC (December 2018). "Acupuncture and related interventions for the treatment of symptoms associated with carpal tunnel syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (9): CD011215. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011215.pub2. PMC 6361189. PMID 30521680.

- Olsen, K. M.; Knudson, D. V. (2001). "Change in Strength and Dexterity after Open Carpal Tunnel Release". International Journal of Sports Medicine. 22 (4): 301–3. doi:10.1055/s-2001-13815. PMID 11414675.

- King, Bradley A.; Stern, Peter J.; Kiefhaber, Thomas R. (2013). "The incidence of trigger finger or de Quervain's tendinitis after carpal tunnel release". Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume). 38 (1): 82–3. doi:10.1177/1753193412453424. PMID 22791612. S2CID 30644466.

- Katz, Jeffrey N.; Losina, Elena; Amick, Benjamin C.; Fossel, Anne H.; Bessette, Louis; Keller, Robert B. (2001). "Predictors of outcomes of carpal tunnel release". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 44 (5): 1184–93. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1184::AID-ANR202>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 11352253.

- Ruch, DS; Seal, CN; Bliss, MS; Smith, BP (2002). "Carpal tunnel release: efficacy and recurrence rate after a limited incision release". Journal of the Southern Orthopaedic Association. 11 (3): 144–7. PMID 12539938.

- Karthik, K.; Nanda, Rajesh; Stothard, John (5 September 2016). "Recurrent Carpal Tunnel Syndrome—Analysis of the Impact of Patient Personality in Altering Functional Outcome Following a Vascularised Hypothenar Fat Pad Flap Surgery". Journal of Hand and Microsurgery. 04 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1007/s12593-011-0051-x. PMC 3371121. PMID 23730080.

- Amadio, Peter C. (2007). "History of carpal tunnel syndrome". In Luchetti, Riccardo; Amadio, Peter C. (eds.). Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Berlin: Springer. pp. 3–9. ISBN 978-3-540-22387-0.

- Paget J (1854) Lectures on surgical pathology. Lindsay & Blakinston, Philadelphia

- Fuller, David A. (September 22, 2010). "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". eMedicine. Archived from the original on July 27, 2010.

- Marie P, Foix C (1913). "Atrophie isolée de l'éminence thenar d'origine névritique: role du ligament annulaire antérieur du carpe dans la pathogénie de la lésion". Rev Neurol. 26: 647–649.

- Putnam JJ (1880). "A series of cases of paresthesia, mainly of the hand, or periodic recurrence, and possibly of vaso-motor origin". Archives of Medicine. 4: 147–162.

- Hunt JR (1914). "The neural atrophy of the muscle of the hand, without sensory disturbances". Rev Neurol Psych. 12: 137–148.

- Moersch FP (1938). "Median thenar neuritis". Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 13: 220.

- Phalen GS, Gardner WJ, Lalonde AA (1950). "Neuropathy of the median nerve due to compression beneath the transverse carpal ligament". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1 (1): 109–112. doi:10.2106/00004623-195032010-00011. PMID 15401727.

- Gilliatt RW, Wilson TG (1953). "A pneumatic-tourniquet test in the carpal-tunnel syndrome". Lancet. 262 (6786): 595–597. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(53)90327-4. PMID 13098011.

- Learmonth JR (1933). "The principle of decompression in the treatment of certain diseases of peripheral nerves". Surg Clin North Am. 13: 905–913.

- Amadio PC (1995). "The first carpal tunnel release?". J Hand Surg: British & European. 20 (1): 40–41. doi:10.1016/s0266-7681(05)80013-0. PMID 7759932. S2CID 534160.

- Chow JC (1989). "Endoscopic release of the carpal tunnel ligament: a new technique for carpal tunnel syndrome". Arthroscopy. 6 (4): 288–296. doi:10.1016/0749-8063(90)90058-l. PMID 2264896.

External links

- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Fact Sheet (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke) Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- NHS website carpal-tunnel.net provides a free to use, validated, online self diagnosis questionnaire for CTS

- "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.