Casa Rosada

The Casa Rosada (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈkasa roˈsaða], English: Pink House) is the office of the president of Argentina. The palatial mansion is known officially as Casa de Gobierno ("House of Government" or "Government House"). Normally, the president lives at the Quinta de Olivos, the official residence of the president of Argentina, which is located in Olivos, Greater Buenos Aires. The characteristic color of the Casa Rosada is baby pink, and it is considered one of the most emblematic buildings in Buenos Aires. The building also houses a museum, which contains objects relating to former presidents of Argentina. It has been declared a National Historic Monument of Argentina.

| Casa Rosada | |

|---|---|

Main façade as seen from Plaza de Mayo | |

Location in Buenos Aires | |

| Alternative names | Casa de Gobierno ("House of Government") |

| General information | |

| Type | Official workplace of the President of Argentina |

| Architectural style | Italianate–Eclectic |

| Address | Balcarce 50 |

| Town or city | Buenos Aires |

| Country | Argentina |

| Coordinates | 34°36′29″S 58°22′13″W |

| Current tenants | Government of Argentina |

| Construction started |

|

| Completed |

|

| Demolished | 1938 (partial) |

| Client | Government of Argentina |

| Owner | Government of Argentina |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 4 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Main contractor |

|

National Historic Monument of Argentina | |

History

The Casa Rosada sits at the eastern end of the Plaza de Mayo, a large square which since the 1580 foundation of Buenos Aires has been surrounded by many of the most important political institutions of the city and of Argentina. The site, originally at the shoreline of the Río de la Plata, was first occupied by the "Fort of Juan Baltazar of Austria", a structure built on the orders of the founder of Buenos Aires, Captain Juan de Garay, in 1594. Its 1713 replacement by a masonry structure (the "Castle of San Miguel") complete with turrets made the spot the effective nerve center of colonial government. Following independence, President Bernardino Rivadavia had a Neoclassical portico built at the entrance in 1825, and the building remained unchanged until, in 1857, the fort was demolished in favor of a new customs building. Under the direction of British Argentine architect Edward Taylor, the Italianate structure functioned as Buenos Aires' largest building from 1859 until the 1890s.[1][2]

The old fort's administrative annex, which survived the construction of Taylor's Customs House, was enlisted as the presidential offices by Bartolomé Mitre in the 1860s and his successor, Domingo Sarmiento, who beautified the drab building with patios, gardens and wrought-iron grillwork, had the exterior painted pink reportedly in order to defuse political tensions by mixing the red and white colors of the country's two opposing political parties: red was the color of the Federalists, while white was the color of the Unitarians.[3] An alternative explanation suggests that the original paint contained cow's blood to prevent damage from the effects of humidity. Sarmiento also authorized the construction of the Central Post Office next door in 1873, commissioning Swedish Argentine architect Carl Kihlberg, who designed this, one of the first of Buenos Aires' many examples of Second Empire architecture.[1]

Presiding over an unprecedented socio-economic boom, President Julio Roca commissioned architect Enrique Aberg to replace the cramped State House with one resembling the neighboring Central Post Office in 1882. Following works to integrate the two structures, Roca had architect Francesco Tamburini build the iconic Italianate archway between the two in 1884. The resulting State House, still known as the "Rose House", was completed in 1898 following its eastward enlargement, works which resulted in the destruction of the customs house.[1]

A Historical Museum was created in 1957 to display presidential memorabilia and selected belongings, such as sashes, batons, books, furniture, and three carriages. The remains of the former fort were partially excavated in 1984-85, and the uncovered structures were incorporated into the Museum of the Casa Rosada. Located behind the building, these works led to the rerouting of Paseo Colón Avenue, unifying the Casa Rosada with Parque Colón (Columbus Park) behind it. Plans were announced in 2009 for the restoration of surviving portions of Taylor's Customs House, as well.[4]

The Casa Rosada itself in 2006 underwent extensive renovation delayed by the 2001 economic crisis. The first phase was completed for the 2010 bicentennial of the May Revolution that led to independence, with a second phase begun in 2017.[1]

Evolution of the Casa Rosada

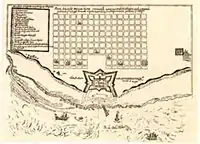

The Fort

In 1536, Don Pedro de Mendoza established a settlement near the mouth of the Riachuelo de los Navíos, called Nuestra Señora del Buen Ayre. In 1580, Juan de Garay founded the city at the place which was to be the Plaza Mayor (nowadays Plaza de Mayo), naming it Santísima Trinidad while the port retained the name of the original settlement; the "Royal Fort of Don Juan Baltasar de Austria" was built in 1594. It was replaced in 1713 by a more solid construction with turrets, sentry boxes, a moat and a drawbridge that upon being completed in 1720 was given the name of "Castillo San Miguel" (St. Michael's Castle). President Bernardino Rivadavia modified the fort in 1820, and the drawbridge was replaced by a neoclassical portico. The site which was for defence purposes at that time and also seat of the Spanish and Home governments, is where Government House currently stands.[2]

In the Pink House Museum one of its cannon holes can be found in part of a storage room of the Royal Treasury's warehouse.[2]

New Customs House

.jpg.webp)

Under the direction of the English architect, Edward Taylor, the New Customs House was built in 1855 back to back with the rear walls of the Fort, facing the river. It is the first public building of great size built by the young mercantile State of Buenos Aires; its semicircular shape had five floors for depots and fifty one storage rooms with arched ceilings, surrounded by loggias. From the central tower at the top of which there was a clock and a beacon, stretched out a 300 m pier providing wharfaging for ships of greater draught to cast their anchors. Via two side ramps carts, loaded with goods, accessed the manoeuvring dock. It was used for almost forty years and it was demolished down to the first floor by the Madero Port project and its foundations are buried under what is today Colón Park.[2]

The Post Office Palace

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

President Domingo Sarmiento ordered the construction of the Postal headquarters in 1873 on open ground that had remained after the south wing of the Buenos Aires Fort had been demolished. This project was carried out by the Swedish architect Carlos Kihlberg (Swedish:Carl August Kihlberg), with a design inspired by Italian Renaissance Revival architecture and French Second Empire details.[2]

As Government House looked totally insignificant compared to this new post office building, President Julio Roca called upon the department of civil engineers to produce a project for extending and repairing the former, and the project submitted by the Swedish architect, Enrique Aberg (Swedish: Henrik Åberg) was adopted. It proposed the demolition of the Fort and the construction of another building, identical to the post office, differentiating it by incorporating a long balcony on the first floor for the use of authorities during public festivities and parades. This was the end of the Fort of which only some walls and one of the cannon holes can be seen in the current Government House museum. For aesthetic reasons and to solve the problem of lack of space it was later decided that the Post Office building be incorporated into Government House. Architect Francesco Tamburini was commended this task. He designed a great central archway to join the two buildings into one, bringing together the surroundings where the New Customs House and Old Arcade were, interpreted by the architect as enveloping a central main axis on which the entrances were located, emphasized by a higher archway.[2]

The Palace

The outlay of the buildings is three stories on Balcarce Street and four stories plus a basement/galleries of Government House Museum, on Avenida Paseo Colón, practically covering the footage of a whole bloc. All the original rooms that are on the three main façades have direct ventilation and lighting, while the original internal rooms were designed in such a way that ventilation and light should come from the loggia that surround internal patios designed for this purpose. All, except one, were crowned by skylights, of which only two remain. The original structure consists of packwalls of varying thickness and slabs supported by brick counter ceilings with steel or wood roof lines, according to the sector. Following a long process of construction the current building was officially inaugurated in 1898, during the second presidency of General Julio Roca.[2]

Rooms

The president sits at his or her office on a seat known as the "Seat of Rivadavia". The seat itself did not actually belong to Bernardino Rivadavia, the first president of Argentina, but is instead a homage to the early statesman.[5]

The Hall of Busts houses marble busts of the many presidents of Argentina, made by diverse artists both national and international. The list, however, is not exhaustive, and subjected to political biases. President Néstor Kirchner ordered in 2006 the removal of all busts of presidents that took power during coups, but the busts of José Félix Uriburu, Pedro Pablo Ramírez and Edelmiro Julián Farrell were spared and finally removed during the administration of Mauricio Macri. President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner broke the timeline order of the busts, and placed instead the busts of Kirchner, Raúl Alfonsín, Hipólito Yrigoyen and Juan Perón in a prominent location. The administration of Macri reordered the busts under the supervision of the National Academy of History of Argentina, and Alberto Fernández restored the order set by Cristina Kirchner. The internal regulations specify that presidents should have a bust 8 years after they leave office, but for varied reasons Isabel Perón, Carlos Menem, Fernando de la Rúa, Adolfo Rodríguez Saá and Eduardo Duhalde do not have busts as of 2022.[6]

Interior

The President's office

The President's office Christ the King Chapel

Christ the King Chapel The Stained Glass Gallery

The Stained Glass Gallery The Hall of Busts

The Hall of Busts The Palm Tree Patio

The Palm Tree Patio_Buenos_Aires%252C_Argentina.jpg.webp) The Salón Blanco

The Salón Blanco The Salón Blanco

The Salón Blanco The North Hall

The North Hall The South Hall

The South Hall Hall of Argentine Bicentennial Women

Hall of Argentine Bicentennial Women Hall of Bicentennial Patriots of Latin America

Hall of Bicentennial Patriots of Latin America Hall of Bicentennial Thinkers and Writers

Hall of Bicentennial Thinkers and Writers Hall of Argentine Bicentennial Scientists

Hall of Argentine Bicentennial Scientists Hall of Argentine Bicentennial Painters and Paintings (Blue Hall)

Hall of Argentine Bicentennial Painters and Paintings (Blue Hall) Presidential elevator

Presidential elevator Francia Stairs of Honour

Francia Stairs of Honour Italia Stairs of Honour

Italia Stairs of Honour Hall of Honour

Hall of Honour

Exterior

Entrance on Rivadavia Street

Entrance on Rivadavia Street The presidential balcony

The presidential balcony Monument to Christopher Columbus, behind the Casa Rosada. This monument was removed and placed near Jorge Newbery Airfield.

Monument to Christopher Columbus, behind the Casa Rosada. This monument was removed and placed near Jorge Newbery Airfield. The Italianate portico

The Italianate portico Portico

Portico View of the north wing and the porte-cochère

View of the north wing and the porte-cochère.jpg.webp) Casa Rosada (center) in 1888

Casa Rosada (center) in 1888.jpg.webp) Casa Rosada (1876)

Casa Rosada (1876) View from the river (1920), with fountain where now is Plaza Colon

View from the river (1920), with fountain where now is Plaza Colon

See also

- Palace of the Argentine National Congress

- Palace of Justice of the Argentine Nation

- List of National Historic Monuments of Argentina

- President of Argentina

References

- Museum of the Casa Rosada: history Archived June 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Casa Rosada: History (in Spanish)

- Daniel Lewis, "Casa Rosada" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996, vol. 2, p. 2 citing James R. Scobie, Argentina: A City and a Nation, 2d edition (1971) pp. 163, 165.

- "La musealización del patrimonio arqueológico de la Aduana Taylor de la ciudad de Buenos Aires" (PDF). Revista del Museo de La Plata (in Spanish). 2013.

- Cuando Rivadavia se fue con el sillón (in Spanish)

- Camila Dolabjian (March 29, 2022). "Casa Rosada. Secretos, caprichos y pagos en dólares detrás de los bustos presidenciales" [Casa Rosada: Secrets, whims and payments in dollars behind the presidential busts] (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved March 29, 2022.