Central line (London Underground)

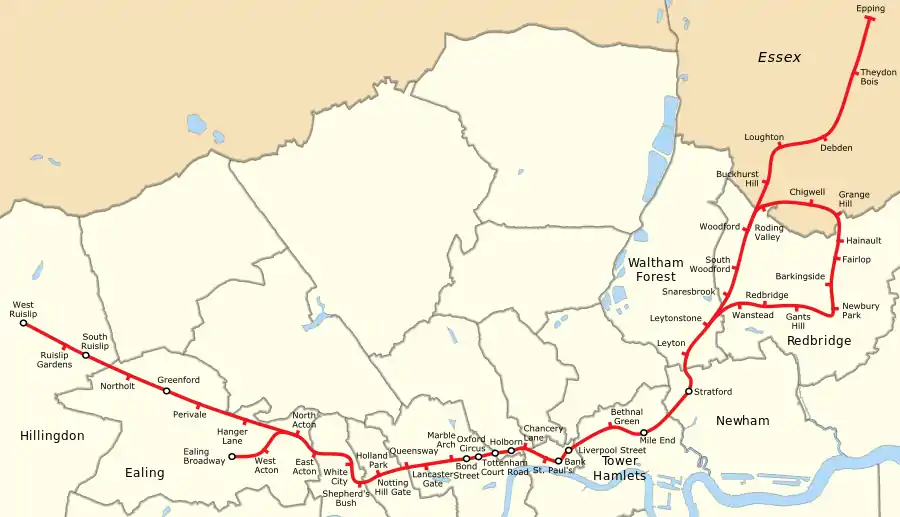

The Central line is a London Underground line that runs through central London, from Epping, Essex, in the north-east to Ealing Broadway and West Ruislip in west London. Printed in red on the Tube map, the line serves 49 stations over 46 miles (74 km).[3] It is one of only two lines on the Underground network to cross the Greater London boundary, the other being the Metropolitan line. One of London's deep-level railways, Central line trains are smaller than those on British main lines.

| Central line | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A 1992 stock Central line train leaving Theydon Bois | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 49 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Colour on map | Red | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | tfl.gov.uk | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Rapid transit | ||||||||||||||||||||

| System | London Underground | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Depot(s) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | 1992 Stock | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ridership | 260.916 million (2011/12)[2] passenger journeys | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 30 July 1900 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Last extension | 1949 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 74 km (46 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Deep Tube | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The line was opened as the Central London Railway in 1900, crossing central London on an east–west axis along the central shopping street of Oxford Street to the financial centre of the City of London. It was later extended to the western suburb of Ealing. In the 1930s, plans were created to expand the route into the new suburbs, taking over steam-hauled outer-suburban routes to the borders of London and beyond to the east. These projects were mostly realised after Second World War, when construction stopped and the unused tunnels were used as air-raid shelters and factories. However, suburban growth was limited by the Metropolitan Green Belt: of the planned expansions one (to Denham, Buckinghamshire) was cut short and the eastern terminus of Ongar ultimately closed in 1994 due to low patronage; part of this section between Epping and Ongar later became the Epping Ongar Railway. The Central line has mostly been operated by automatic train operation since a major refurbishment in the 1990s, although all trains still carry drivers. Many of its stations are of historic interest, from turn-of-the-century Central London Railway buildings in west London to post-war modernist designs on the West Ruislip and Hainault branches, as well as Victorian-era Eastern Counties Railway and Great Eastern Railway buildings east of Stratford, from when the line to Epping was a rural branch line.

In terms of total passengers, the Central line is the second busiest on the Underground. In 2016/17 over 280 million passenger journeys were recorded on the line.[4] As of 2013, it operated the second-most frequent service on the network, with 34 trains per hour (tph) operating for half-an-hour in the westbound direction during the morning peak, and between 27 and 30 tph during the rest of the peak.[5] The Elizabeth Line, which began most of its core operation from 24 May 2022,[6] provides interchanges with the Central line at Stratford, Liverpool Street, Tottenham Court Road, Ealing Broadway,[7] and Bond Street, relieving overcrowding.

History

Central London Railway

The Central London Railway (CLR) was given permission in 1891 for a tube line between Shepherd's Bush and a station at Cornhill, and the following year an extension to Liverpool Street was authorised, with a station at Bank instead of at Cornhill.[8] The line was built following the streets above rather than running underneath buildings, because purchase of wayleave under private properties would have been expensive,[lower-alpha 1] and as a result one line runs above another in places, with platforms at different levels at St Paul's, Chancery Lane and Notting Hill Gate stations.[9] The tunnels were bored with the nominal diameter of 11 feet 8+1⁄4 inches (3.562 m), increased on curves, reduced to 11 feet 6 inches (3.51 m) near to stations.[10] The tunnels generally rise approaching a station, to aid braking, and fall when leaving, to aid acceleration.[9]

The Central London Railway was the first underground railway to have the station platforms illuminated electrically.[11] All the platforms were lit by Crompton automatic electric arc lamps, and other station areas by incandescent lamps. Both the City and South London Railway and the Waterloo and City Railway were lit by gas lamps, primarily because the power stations for these lines were designed with no spare capacity to power electric lighting. With the white glazed tiling, all underground Central London Railway platforms were very brightly lit. The use of electric lighting was further made possible because the Central London was also the first tube railway to use AC electrical distribution[lower-alpha 2] and the substation transformers were easily able to provide convenient voltages to run the lighting. Earlier tube lines generated DC power at the voltage required to run the trains (500 volts).

The line between Shepherd's Bush and Bank was formally opened on 30 June 1900, public services beginning on 30 July.[12] With a uniform fare of 2d the railway became known as the "Twopenny Tube".[12] It was initially operated by electric locomotives hauling carriages, but the locomotive's considerable unsprung weight[lower-alpha 3] caused much vibration in the buildings above the line, and the railway rebuilt the locomotives to incorporate geared drives. This allowed higher-speed and lighter motors to be used, which reduced the overall weight of the locomotive as well as the unsprung weight. The railway also tried an alternative approach: it converted four coaches to accommodate motors and control gear. Two of these experimental motor coaches were used in a 6-coach train, the control gear being operated by the system used on the Waterloo and City Railway.[lower-alpha 4] The modified locomotives were a considerable improvement, but the motor coaches of an even lower weight were much better still. The CLR ordered 64 new motor cars[lower-alpha 5] designed to use Sprague's recently developed traction control system. The CLR was exclusively using the resulting electric multiple units by 1903.[13]

In July 1907, the fare was increased to 3d for journeys of more than seven or eight stations. The line was extended westwards with a loop serving a single platform at Wood Lane for the 1908 Franco-British Exhibition. A reduced fare of 1d, for a journey of three or fewer stations, was introduced in 1909, and season tickets became available from 1911. The extension to Liverpool Street opened the following year, providing access to the Great Eastern station and the adjacent Broad Street station by escalators. The Central London Railway was absorbed into the Underground Group on 1 January 1913.[14]

In 1911, the Great Western Railway won permission for a line from Ealing Broadway to a station near to the CLR's Shepherd's Bush station, with a connection to the West London Railway, and agreement to connect the line to the Central London Railway and for the CLR to run trains to Ealing Broadway. Construction of the extension from the CLR to Ealing Broadway started in 1912[15] but opening was delayed by World War I. The CLR purchased new rolling stock for the extension, which arrived in 1915 and was stored before being lent to the Bakerloo line. The rolling stock returned when the extension opened in 1920.[16]

In 1912, plans were published for a railway from Shepherd's Bush to Turnham Green and Gunnersbury,[17] allowing the Central London Railway to run trains on London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) tracks to Richmond. The route was authorised in 1913[18] but work had not begun by the outbreak of war the following year.[19] In 1919, an alternative route was published, with a tunnelled link to the disused L&SWR tracks south of their Shepherd's Bush station then via Hammersmith (Grove Road) railway station.[20] Authorisation was granted in 1920,[21][19] but the connection was never built, and the L&SWR tracks were used by the Piccadilly line when it was extended west of Hammersmith in 1932.[22]

London Transport and the Second World War

On 1 July 1933, the Central London Railway and other transport companies in the London area were amalgamated to form the London Passenger Transport Board, generally known as London Transport.[23] The railway was known as the "Central London Line", becoming the "Central line" in 1937.[24] The 1935–40 New Works Programme included a major expansion of the line. To the west new tracks were to be built parallel with the Great Western Railway's New North Main Line as far as Denham. To the east, new tunnels would run to just beyond Stratford station, where the line would be extended over the London & North Eastern Railway suburban branch to Epping and Ongar in Essex, as well as a new underground line between Leytonstone and Newbury Park mostly under Eastern Avenue so as to serve the new suburbs of north Ilford and the Hainault Loop.[25] Platforms at central London stations were to be lengthened to allow for 8-car trains.[25]

Construction started, the tunnels through central London being expanded and realigned and the stations lengthened, but it proved impossible to modify Wood Lane station to take 8-car trains and a new station at White City was authorised in 1938.[26] The line was converted to the London Underground four-rail electrification system in 1940.[27] The positive outer rail is 40 mm (1.6 in) higher than on other lines, because even after reconstruction work the tunnels are slightly smaller. Most of the tunnels for the extensions to the east of London had been built by 1940, but work slowed due to the outbreak of the Second World War until eventually suspended in June.[27] The unused tunnels between Leytonstone and Newbury Park were equipped by the Plessey Company as an aircraft components factory, opening in March 1942 and employing 2,000 people.[28] Elsewhere, people used underground stations as night shelters during air raids. The unopened Bethnal Green station had space for 10,000 people. In March 1943, 173 people died there when a woman entering the shelter fell at the bottom of the steps and those following fell on top of her.[28]

Construction restarted after the war, and the western extension opened as far as Greenford in 1947[31] and West Ruislip in 1948.[32] The powers to extend the line to Denham were never used due to post-war establishment of the Green Belt around London, which restricted development of land in the area.[32] The eastern extension opened as far as Stratford in December 1946, with trains continuing without passengers to reverse in the cutting south of Leyton.[33] In 1947, the line opened to Leytonstone, and then Woodford and Newbury Park.[34] Stations from Newbury Park to Woodford via Hainault and from Woodford to Loughton were served by tube trains from 1948.[32] South of Newbury Park, the west-facing junction with the main line closed in the same year to allow expansion of Ilford carriage depot.[35] The extension transferred to London Underground management in 1949, when Epping began to be served by Central line trains. The single line to Ongar was served by a steam autotrain operated by British Rail (BR) until 1957, when the line was electrified.[36] BR trains accessed the line via a link from Temple Mills East to Leyton.[37]

The Central line stations east of Stratford kept their goods service for a time, being worked from Temple Mills, with the Hainault loop stations served via Woodford.[37] The BR line south of Newbury Park closed in 1956[35] and Hainault loop stations lost their goods service in 1965, the rest of the stations on the line following in 1966. Early morning passenger trains from Stratford (Liverpool Street on Sundays) ran to Epping or Loughton until 1970.[38] The single-track section from Epping to Ongar was electrified in 1957[39] and then operated as a shuttle service using short tube trains. However, carrying only 100 passengers a day and losing money, the section closed in 1994, and is now used by the heritage Epping Ongar Railway.[40]

The entire Central line was shut between January and March 2003, after 32 passengers were injured when a train derailed at Chancery Lane due to a traction motor falling on to the track. The line was not fully reopened until June.[41][42] In 2003, the infrastructure of the Central line was partly privatised in a public–private partnership, managed by the Metronet consortium. Metronet went into administration in 2007, and Transport for London took over its responsibilities.[43]

Route

Map

Railway line

Central line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Central line is 46 miles (74 km) long and serves 49 stations.[3][44] The line is predominantly double-track, widened to three tracks for short sections south of Leytonstone and west of White City; no track is shared with any other line, though some sections do run parallel to other routes. Total track length is 91.4 miles (147.1 km), of which 32.8 miles (52.8 km) is in tunnel;[3][45] this track is electrified with a four-rail DC system: a central conductor rail is energised at −210 V and a rail outside the running rail at +420 V, giving a potential difference of 630 V.[46]

The single-track line north of Epping, which closed in 1994, is now the Epping Ongar heritage railway. As of May 2013 shuttle services operate at weekends between North Weald and Ongar and North Weald and Coopersale.[47] These do not call at Blake Hall, as the station platform was removed by London Transport after the station closed, and the remaining building is now a private residence.

The section between Leyton and just south of Loughton is the oldest railway alignment in use on the current London Underground system, having been opened on 22 August 1856 by the Eastern Counties Railway (ECR). Loughton to Epping was opened on 24 April 1865 by the ECR's successor, the Great Eastern Railway (GER), along with the section to Ongar. The Hainault Loop was originally the greater part of the Fairlop Loop opened by the GER on 1 May 1903.[48]

The line has three junctions:

- Woodford Junction is a flat junction

- north of Leytonstone the branch to Newbury Park descends into tube tunnels under the older route to Woodford

- west of North Acton there is another burrowing junction separating the lines to Ealing Broadway and West Ruislip.[45]

The line has the shortest escalator on the London Underground system, at Stratford (previously at Chancery Lane), with a rise of 4.1 metres (13 ft)[49] and, at Stratford and Greenford, the only stations where escalators take passengers up to the trains. That at Greenford was the last escalator with wooden treads on the system until it was replaced in March 2014. They were exempt from fire regulations because they were outside the tunnel system.[50][51]

The line has the shallowest underground Tube platforms on the system, at Redbridge, just 7.9 metres (26 ft) below street level, and the sharpest curve, the Caxton Curve, between Shepherds Bush and White City.[3]

List of stations

Open stations

| Station | Image | Distance between stations (km)[52] | Opened/[53]services started | Branch | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Ruislip |  |

n/a | 21 November 1948 | Ruislip branch | Connects with National rail services. Opened as Ruislip & Ickenham in 1906 by Great Western and Great Central Joint Committee (GW&GCJC), renamed West Ruislip (for Ickenham) in 1947; the suffix was later dropped.[54] | |

| Ruislip Gardens |  |

2.04 | 21 November 1948 | Ruislip branch | Opened in 1934 by GW&GCJC, main line services withdrawn 1958.[55] | |

| South Ruislip |  |

0.86 | 21 November 1948 | Ruislip branch | Connects with National rail services. Opened as Northolt Junction by GW&GCJC in 1908, renamed South Ruislip & Northolt Junction in 1932, and renamed in 1947.[56] | |

| Northolt |  |

2.28 | 21 November 1948 | Ruislip branch | Replaced a nearby GWR station that had opened in 1907.[56] | |

| Greenford |  |

1.78 | 30 June 1947 | Ruislip branch | Connects with National rail services to West Ealing (in bay platform). GWR station opened in 1904.[57] The station was the last one to retain a wooden escalator, replaced in 2014 by the first incline lift on the Underground.[58] | |

| Perivale |  |

1.69 | 30 June 1947 | Ruislip branch | Opened by GWR as "Perivale Halt" in 1904, closed 1915–20; Halt suffix lost in 1922.[59] | |

| Hanger Lane |  |

2.10 | 30 June 1947 | Ruislip branch | ||

| Ealing Broadway |  |

n/a | 3 August 1920 | Ealing branch | Connects with District line, Elizabeth line and National rail services. Opened by District Railway in 1879, link to main-line station opened in 1965/6.[60] | |

| West Acton |  |

1.53 | 5 November 1923 | Ealing branch | ||

| North Acton |  |

from Hanger Lane 2.49

from West Acton 1.77 |

5 November 1923 | Main route | GWR station opened in 1904, moved to its current position in 1913 and closed in 1947.[61] | |

| East Acton |  |

1.11 | 3 August 1920 | Main route | Right-hand running ends some distance southeast of the station from White City. | |

| White City |  |

2.06 | 23 November 1947 | Main route | Connects with Circle and Hammersmith & City lines from Wood Lane. Trains run right-handed through this station | |

| Shepherd's Bush |  |

1.16 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | Refurbished in 2008. To the west of the station, right-hand running starts en route to White City. | |

| Holland Park |  |

0.87 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | ||

| Notting Hill Gate |  |

0.61 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | Connects with Circle and District lines. | |

| Queensway |  |

0.69 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | Opened as Queens Road; renamed 1 September 1946 | |

| Lancaster Gate |  |

0.90 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | ||

| Marble Arch |  |

1.20 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | ||

| Bond Street |  |

0.55 | 24 September 1900 | Main route | Connects with Jubilee line and Elizabeth line, the latter since 24 October 2022. | |

| Oxford Circus |  |

0.66 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | Connects with Bakerloo and Victoria lines. | |

| Tottenham Court Road |  |

0.58 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | Connects with Northern line and Elizabeth line, the latter since 24 May 2022. Opened as Oxford Street; renamed 9 March 1908. | |

| Holborn |  |

0.88 | 25 September 1933 | Main route | Originally opened as a Piccadilly station on 15 December 1906, Central line platforms opened later and station renamed Holborn (Kingsway); the suffix was later dropped. | |

| Chancery Lane |  |

0.40 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | Renamed Chancery Lane (Gray's Inn) 25 June 1934; the suffix was later dropped | |

| St Paul's |  |

1.03 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | Opened as Post Office; renamed 1 February 1937. Interchangeable from City Thameslink from walking distance. | |

| Bank |  |

0.74 | 30 July 1900 | Main route | Connects with Circle, District, Northern and Waterloo & City lines and DLR. | |

| Liverpool Street |  |

0.74 | 28 July 1912 | Main route | Connects with Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan lines, London Overground, Elizabeth line and National rail services. | |

| Bethnal Green |  |

2.27 | 4 December 1946 | Main route | ||

| Mile End |  |

1.64 | 4 December 1946 | Main route | Cross-platform interchange with District and Hammersmith & City lines. Opened in 1902 for District Railway services.[62] | |

| Stratford |  |

2.83 | 4 December 1946 | Main route | Connects with Jubilee line, London Overground, DLR, Elizabeth line and National Rail services. Opened by Eastern Counties Railway (ECR) in 1839.[63] | |

| Leyton |  |

2.09 | 5 May 1947 | Main route | Opened as Low Leyton by ECR in 1856, renamed in 1868.[64] | |

| Leytonstone |  |

1.62 | 5 May 1947 | Main route | Opened by ECR in 1856.[65] | |

| Wanstead |  |

from Leytonstone 1.72 | 14 December 1947 | Hainault loop | Used during the war as an air-raid shelter and the tunnels as a munitions factory for Plessey electronics. | |

| Redbridge |  |

1.22 | 14 December 1947 | Hainault loop | During the war, the completed tunnels at Redbridge were used by the Plessey company as an aircraft parts factory. | |

| Gants Hill |  |

1.27 | 14 December 1947 | Hainault loop | During the war, it was used as an air-raid shelter and the tunnels as a munitions factory for Plessey electronics. | |

| Newbury Park |  |

2.36 | 14 December 1947 | Hainault loop | Opened 1903 on the GER Ilford to Woodford Fairlop Loop line.[66] | |

| Barkingside |  |

1.11 | 31 May 1948 | Hainault loop | Opened 1903 on the GER Fairlop Loop, closed 1916–19.[67] | |

| Fairlop |  |

1.22 | 31 May 1948 | Hainault loop | Opened 1903 on the GER Fairlop Loop.[68] | |

| Hainault |  |

0.75 | 31 May 1948 | Hainault loop | Opened 1903 on the GER Fairlop Loop, closed 1908–30.[69] | |

| Grange Hill |  |

1.12 | 21 November 1948 | Hainault loop | Opened 1903 on the GER Fairlop Loop.[70] | |

| Chigwell |  |

1.32 | 21 November 1948 | Hainault loop | Opened 1903 on the GER Fairlop Loop.[68] | |

| Roding Valley |  |

2.28 | 21 November 1948 | Hainault loop | Trains continue to Woodford. Opened 1936 by the LNER on the Fairlop Loop.[71] | |

| Snaresbrook |  |

from Leytonstone 1.57 | 14 December 1947 | Epping branch | Opened as Snaresbrook & Wanstead by ECR in 1856, renamed Snaresbrook for Wanstead in 1929, renamed for the transfer to the Central line.[64] | |

| South Woodford |  |

1.29 | 14 December 1947 | Epping branch | Opened by ECR in 1856 as George Lane, and renamed South Woodford (George Lane) in 1937, current name from 1950. "(George Lane)" still appears on some of the platform roundels.[72] | |

| Woodford |  |

from South Woodford 1.80

from Roding Valley 1.33 |

14 December 1947 | Epping branch/Hainault loop | Opened by ECR in 1856.[65] | |

| Buckhurst Hill |  |

from Woodford 2.31 | 21 November 1948 | Epping branch | Opened as a single line by ECR in 1856, moved slightly when line doubled in 1881/2.[73] | |

| Loughton |  |

1.83 | 21 November 1948 | Epping branch | Opened by ECR in 1856, moved when line was extended to Ongar in 1865, and again in 1940.[65] | |

| Debden |  |

2.02 | 25 September 1949 | Epping branch | Opened by GER in 1865 as Chigwell Road, renamed Chigwell Lane later the same year. Closed 1916–19, named changed when transferred to Central line.[74] | |

| Theydon Bois |  |

3.34 | 25 September 1949 | Epping branch | Opened by GER in 1865 as Theydon, renamed later the same year.[75] | |

| Epping | 2.54 | 25 September 1949 | Epping branch | Opened by GER in 1865.[76] | ||

Former stations

- On the Denham extension, aborted due to its location in a sparsely populated area within the Metropolitan Green Belt:

- Denham; it was never connected.

- Harefield Road; it was never opened.

- Wood Lane; closed 22 November 1947,[53] replaced by White City.

- British Museum; closed 24 September 1933,[53] replaced by two new platforms at the Piccadilly line's Holborn station.

- On the shuttle service from Epping to Ongar, closed in September 1994:

- North Weald; it was first served by the Central line on 25 September 1949,[53] taking over the Great Eastern Railway (GER)'s services. It closed on 30 September 1994.[53]

- Blake Hall; it was first served by the Central line 25 September 1949. The station closed on 31 October 1981.[53]

- Ongar; it was first served by the Central line, which took over the GER services, on 25 September 1949.[53] It was closed on 30 September 1994[53]

Rolling stock

Former rolling stock

When the railway opened in 1900, it was operated by electric locomotives hauling carriages with passengers boarding via lattice gates at each end. The locomotives had a large unsprung mass, which caused vibrations that could be felt in the buildings above the route. After an investigation by the Board of Trade, by 1903 the carriages had been adapted to run as trailers and formed with new motor cars into electric multiple units.[77] The Central London Railway trains normally ran with six cars, four trailers and two motor-cars, although some trailers were later equipped with control equipment to allow trains to be formed with 3 cars.[78] Work started in 1912 on an extension to Ealing Broadway, and new more powerful motor-cars were ordered. These arrived in 1915, but completion of the extension was delayed because of World War I, and the cars stored. In 1917, they were lent to the Bakerloo line, where they ran on the newly opened extension to Watford Junction. Returning in 1920/21, and formed with trailers converted from the original carriages, they became the Ealing Stock.[16] In 1925–28, the trains were rebuilt, replacing the gated ends with air-operated doors, allowing the number of guards to be reduced to two.[79] After reconstruction of the Central London Railway tunnels, the trains were replaced by Standard Stock transferred from other lines and the last of the original trains ran in service in 1939.[80]

The Standard Stock ran as 6-car trains until 1947, when 8-car trains became possible after Wood Lane was replaced by a new station at White City. More cars were transferred from other lines as they were replaced by 1938 Stock.[81] In the early 1960s, there was a plan to re-equip the Piccadilly line with new trains and transfer its newer Standard Stock to the Central line to replace the older cars there, some of which had been stored in the open during the Second World War and were becoming increasingly unreliable.[82] However, after the first deliveries of 1959 Stock were running on the Piccadilly it was decided to divert this stock to the Central line, together with extra non-driving motor cars to lengthen the trains from 7-car to 8-car. 1962 Stock was ordered to release the 1959 Stock for the Piccadilly line. The last Standard Stock train ran on the Central line in 1963,[83] and by May 1964 all 1959 Stock had been released to the Piccadilly line.[84]

The single track section from Epping to Ongar was not electrified until 1957, prior to which the service was operated by an autotrain, carriages attached to a steam locomotive capable of being driven from either end, hired from British Railways, and an experimental AEC three-car lightweight diesel multiple unit operated part of the shuttle service Monday-Friday in June 1952.[39] Upon electrification, 1935 Stock was used,[85] until replaced by four-car sets of 1962 Stock specially modified to cope with the limited current. The section closed in 1994, and is now the heritage Epping Ongar Railway.

A shuttle operated on the section from Hainault to Woodford after a train of 1960 Stock was modified to test the automatic train operation system to be used on the Victoria line. As each 1967 Stock train was delivered, it ran in test for three weeks on the shuttle service.[86]

Current rolling stock

When the signalling on the Central line needed replacement by the late 1980s, it was decided to bring forward the replacement of the 1962 Stock, due at about the time as the replacement of the 1959 Stock. The signalling was to be replaced with an updated version of the Automatic Train Operation (ATO) system used on the Victoria line, the line traction supply boosted and new trains built.[87] Prototype trains were built with two double and two single doors hung on the outside of each carriage of the train, and with electronic traction equipment that gave regenerative and rheostatic braking.[88]

In accordance with this plan, the first 8-car trains of 1992 Stock entered service in 1993,[89][90] and while the necessary signalling works for ATO were in progress, One Person Operation (OPO) was phased in between 1993 and 1995.[40] Automatic train protection was commissioned from 1995 to 1997 and ATO from 1999 to 2001, with a centralised control centre in West London.[3]

The trains are currently undergoing a refurbishment programme known as CLIP (Central Line Improvement Programme). The trains will have passenger information displays, wheelchair areas and CCTV installed. The programme, which includes updating motors, lighting, doors and seats, is being carried out at a new Train Modification Unit (TMU) in Acton and is expected to complete in late 2023.[91]

Depots

There are three depots: Ruislip, Hainault and White City.[1] White City depot first opened in 1900 when the initial line went into operation; Ruislip and Hainault depots were completed in 1939. During the Second World War, anti-aircraft guns were made at Ruislip Depot and the U.S. Army Transportation Corps assembled rolling stock at Hainault between 1943 and 1945.[92] As part of the construction of the Westfield London shopping centre, the depot at White City was replaced underground, opening in 2007.[93]

Services

During the off-peak, services on the Central line are grouped by branch lines: trains on the West Ruislip branch run to/from Epping, while trains to/from Ealing Broadway run on the Hainault Loop. Services at peak times are less structured, and trains can run between any two terminus stations at irregular intervals (e.g. from Ealing Broadway to Epping).[94]

As of January 2020, the typical off-peak service, in trains per hour (tph), is:[94]

- 9tph between West Ruislip and Epping;

- 3tph between Northolt and Loughton;

- 3tph between Hainault and Woodford;

- 6tph between Ealing Broadway and Hainault (via Newbury Park);

- 3tph between Ealing Broadway and Newbury Park;

- 3tph between White City and Hainault.

The above services combine to give a total of 24 trains per hour each way (one every 2 minutes and 30 seconds) in the core section between White City and Leytonstone. At peak times, the frequency increases further, with up to 35 trains per hour each way in the core section.

A 24-hour Night Tube service began on the Central line on 19 August 2016, running on Friday and Saturday nights.[95] Night tube services are:

- 3tph between Ealing Broadway and Hainault (via Newbury Park)

- 3tph between White City and Loughton

Peak-time frequency

In September 2013, the frequency in the morning peak period was increased to 35 trains per hour, giving the line the most intensive train service in the UK at the time.[96] Before that date, the Victoria line held the record with 33 trains per hour; it regained it in May 2017 with an increased frequency of 36 trains per hour (one every 100 seconds) during peak periods.[97]

Future and cancelled plans

The Central crosses over the Metropolitan and Piccadilly lines' shared Uxbridge branch near West Ruislip depot, and a single track linking the two routes was laid in 1973. The London Borough of Hillingdon has lobbied TfL to divert some or all Central trains along this to Uxbridge, as West Ruislip station is located in a quiet suburb and Uxbridge is a much more densely populated regional centre. TfL has stated that the link will be impossible until the Metropolitan line's signalling is upgraded in 2017.[98]

The Central line was the first Underground line to receive a complete refurbishment in the early 1990s, including the introduction of new rolling stock.[99] A new generation of deep-level tube trains, as well as signalling upgrades, is planned for the mid-2020s, starting with the Piccadilly line, followed by the Bakerloo line and the Central line.[100]

The proposed Crossrail 2 line, running from south-west to north-east London and due to open by 2030, was planned for a number of years to take over the Epping branch of the Central line between Leytonstone and Epping.[101] As of 2013 the preferred route options for the line no longer include this proposal.[102]

The Central line runs directly below Shoreditch High Street station and an interchange has been desired locally since it opened in 2010. The station would lie between Liverpool Street and Bethnal Green, one of the longest gaps between stations in inner London. Although there would be benefits to this interchange, it was ruled out on grounds of cost, the disruption it would cause to the Central line while being built and because the platforms would be too close to sidings at Liverpool Street and would not be developed until after Crossrail is fully operational.[103]

The developers of the First Central business park at Park Royal, west London, were planning a new station between North Acton and Hanger Lane. This would have served the business park and provided a walking distance interchange with Park Royal station on the Piccadilly line.[104] This is not being actively pursued; London Underground said that the transport benefits of a Park Royal station on the Central line are not sufficiently high to justify the costs of construction.[105]

References

- "London Underground Key Facts". Transport for London. n.d. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "LU Performance Data Almanac" (2011/12 ed.). Transport for London. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "Central line facts". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- "Up to date per line London Underground usage statistics". TheyWorkForYou. 29 April 2018. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Central Line Timetable" (PDF). TfL. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Topham, Gwyn (21 August 2020). "Crossrail delayed again until 2022 and another £450m over budget". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- "Tube Map". TfL. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 52.

- Green 1987, p. 21.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 53.

- Horne 1987, p. 16.

- Day & Reed 2010, pp. 56–57.

- Green 1987, p. 22.

- Day & Reed 2010, pp. 58–59.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 119.

- Bruce 1988, pp. 31–33.

- "No. 28666". The London Gazette. 26 November 1912. pp. 9018–9021.

- "No. 28747". The London Gazette. 19 August 1913. pp. 5929–5931.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 273–274.

- "No. 31656". The London Gazette. 25 November 1919. p. 14473.

- "No. 32009". The London Gazette. 6 August 1920. pp. 8171–8172.

- Green 1987, p. 42.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 110.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 212.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 116.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 124.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 134.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 142.

- Leboff 1994, pp. 88–89.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1141221)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 288.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 294.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 286.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 287, 291.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 291.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, pp. 295–297.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 296.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 347.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 149.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 200.

- Day & Reed 2010, pp. 214–215.

- "Derailment at Chancery Lane, 25 January 2003" (PDF). Health and Safety Executive. March 2006.

- "PPP Performance Report" (PDF). Transport for London. 2010. pp. 7–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- "Key facts". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- "Detailed London Transport Map". cartometro.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- Martin, Andrew (26 April 2012). Underground, Overground: A Passenger's History of the Tube. London: Profile Books. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-84765-807-4. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "Timetable". Epping Ongar Railway. 29 May 2013. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- Brown 2012.

- "Key facts". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "The last wooden escalator". Ian Visits. 16 August 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- "Tube's only wooden escalator to carry last passengers". london24.com. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- "Distance between adjacent Underground stations - a Freedom of Information request to Transport for London". WhatDoTheyKnow. 14 August 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- Rose 2007.

- Leboff 1994, p. 152.

- Leboff 1994, p. 117.

- Leboff 1994, p. 126.

- Leboff 1994, p. 64.

- "Incline lift at Greenford Tube station is UK first" (Press release). Transport for London. 20 October 2015. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- Leboff 1994, p. 108.

- Leboff 1994, p. 42.

- Leboff 1994, p. 97.

- Leboff 1994, p. 92.

- Leboff 1994, p. 160.

- Leboff 1994, p. 86.

- Leboff 1994, p. 87.

- Leboff 1994, p. 96.

- Leboff 1994, p. 18.

- Leboff 1994, p. 54.

- Leboff 1994, p. 65.

- Leboff 1994, p. 63.

- Leboff 1994, p. 115.

- Leboff 1994, p. 127.

- Leboff 1994, p. 27.

- Leboff 1994, p. 41.

- Leboff 1994, p. 134.

- Leboff 1994, p. 53.

- Bruce 1988, pp. 25–29.

- Bruce 1988, p. 30.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, pp. 201–202.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, pp. 247–248.

- Bruce 1988, pp. 71–72.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, pp. 313, 318.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 328.

- Bruce 1988, p. 92.

- Bruce 1988, p. 76.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 338.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 470.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, pp. 471–473.

- Day & Reed 2010, p. 198.

- "Rolling Stock Information Sheets" (PDF). London Underground. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Rullion. "Be a part of the Central Line Improvement Programme". Rullion. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, pp. 294–295.

- "White City Central Line Sidings". Ian Ritchie Architects. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Central line working timetable" (PDF). London Underground Ltd. 26 January 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Standard Night Tube Map (PDF) (Map). Transport for London. May 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2020.

- "Tube improvement plan: Central line". Transport for London. n.d. Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- Templeton, Dan (26 May 2017). "New Victoria Line timetable increases frequency". International Railway Journal. London. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Coombs, Dan (17 June 2011). "Extending Central Line to Uxbridge will cut traffic". Uxbridge Gazette. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011.

- "Tube upgrade plan: Central line". Transport for London. n.d. Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- "Improving the Trains". Transport for London. August 2017.

- "Chelsea-Hackney Line Safeguarding Directions" (PDF). Cross London Rail Links. 5 March 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2007.

- "Crossrail 2: Supporting London's Growth" (PDF). London First. February 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- Hawkins, John. "Meeting Reports: The East London Line Extension" (PDF). London Underground Railway Society.

- First Central Business Park Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Proposed Park Royal Central Line station" (PDF). London Borough of Brent. 20 October 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

Notes

- To encourage the building of tube railways, the wayleave for building under streets was free.

- Power was generated at 5000 volts at 33+1⁄3 Hertz from six 850 kW generators at Wood Lane.

- The CLR locomotives had been designed such that the motor armatures were built directly on the axles. This was intended to reduce noise from gearboxes which would otherwise be necessary.

- Although the Board of Trade forbade this system being used on any future passenger railway, it was used in this case because the trains were experimental and were forbidden to carry fare-paying passengers.

- The CLR adopted the American term of 'car' rather than 'coach' with the introduction of the Electrical Multiple Unit.

Bibliography

- Brown, Joe (1 October 2012). London Railway Atlas (3rd ed.). Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3728-1.

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-293-3.

- Bruce, J Graeme (1988). The London Underground Tube Stock. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-1707-7.

- Croome, D.; Jackson, A (1993). Rails Through The Clay – A History of London's Tube Railways (2nd ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-151-1.

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2010) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground (11th ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-341-9.

- Green, Oliver (1987). The London Underground — An illustrated history. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-1720-4.

- Horne, Mike A.C. (1987). The Central Line: A Short History. North Finchley: Douglas Rose. ISBN 1-870354-01-X. OCLC 59844512. OL 12070417M.

- Leboff, David (1994). London Underground Stations. Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-2226-3.

- Rose, Douglas (December 2007) [1980]. The London Underground: A Diagrammatic History (8th ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-315-0.

External links

- Central line facts Archived 26 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine – Transport for London page with line facts and brief history

- Clive's Underground Line Guide

- A History of the London Tube Maps – 1914 tube map showing proposed extension to Gunnersbury Archived 15 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Epping Ongar Railway – The company currently owning the Epping and Ongar branch and running trains on it.