Chaim Topol

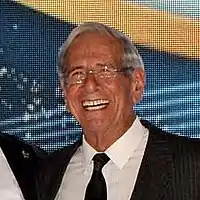

Chaim Topol (Hebrew: חיים טופול; born September 9, 1935), also spelled Haym Topol,[1] mononymously known as Topol,[2] is an Israeli actor, comedian, singer, film producer, author, and illustrator. He is best known for his portrayal of Tevye the Dairyman, the lead role in the musical Fiddler on the Roof, on both stage and screen, having performed this role more than 3,500 times in shows and revivals from the late 1960s through 2009.[2]

Chaim Topol | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Topol in 1971 | |

| Born | September 9, 1935 |

| Nationality | Israeli |

| Other names | Haym Topol Topol |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1957–2015 |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouse | Galia Finkelstein

(m. 1956) |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards |

|

Topol began his acting career during his Israeli army service in the Nahal entertainment troupe, and later toured Israel with kibbutz theatre and satirical theatre companies. He was a co-founder of the Haifa Theatre. His breakthrough film role came in 1964 as the title character in Sallah Shabati, by Israeli writer Ephraim Kishon, for which he won a Golden Globe for Most Promising Newcomer—Male. Topol went on to appear in more than 30 films in Israel and the United States, including Galileo (1975), Flash Gordon (1980) and For Your Eyes Only (1981). He was described as Israel's only internationally recognized entertainer from the 1960s through the 1980s. He won a Golden Globe for Best Actor and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor for his 1971 film portrayal of Tevye, and was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Actor for a 1991 Broadway revival of Fiddler on the Roof.

He is a founder of Variety Israel, an organization serving children with special needs, and Jordan River Village, a year-round camp for Arab and Jewish children with life-threatening illnesses, for which he serves as chairman of the board. In 2015 he was awarded the Israel Prize for lifetime achievement.

Early life

Topol was born on September 9, 1935, in Tel Aviv,[1][3] in what was then Mandatory Palestine (now Israel). His father, Jacob Topol, was Russian and in the early 1930s immigrated to Mandatory Palestine, where he worked as a plasterer;[4][5] he also served in the Haganah paramilitary organization.[6] His mother, Imrela "Rel" (née Goldman) Topol, was a seamstress.[4][7]

Both of Topol's parents had been involved in the Betar Zionist youth movement before immigrating. His father had Hasidic roots, with a mother coming from a family of Gerrer Hasidim, while his father came from Aleksander Hasidim.

Chaim and his two younger sisters grew up in the South Tel Aviv working-class neighborhood of Florentin. As a young child, although he wanted to become a commercial artist, his elementary school teacher, the writer Yemima Avidar-Tchernovitz, saw a theatrical side to him, and encouraged him to act in school plays and read stories to the class.[2]

At age 14 he began working as a printer at the Davar newspaper while pursuing his high school studies at night.[2] He graduated high school at age 17 and moved to Kibbutz Geva. A year later, he enlisted in the Israeli army and became a member of the Nahal entertainment troupe, singing and acting in traveling shows.[2][8] He rose in rank to troupe commander.[2]

Twenty-three days after being discharged from military service on October 2, 1956, and two days after marrying Galia Finkelstein, a fellow Nahal troupe member, Topol was called up for reserve duty in the Sinai Campaign. He performed for soldiers stationed in the desert. After the war, he and his wife settled in Kibbutz Mishmar David, where Topol worked as a garage mechanic.[2] Topol assembled a kibbutz theatre company made up of friends from his Nahal troupe; the group toured four days a week, worked on their respective kibbutzim for two days a week, and had one day off. The theatre company was in existence from early 1957 to the mid-1960s. Topol both sang and acted with the group, doing both "loudly".[2]

Between 1960 and 1964, Topol performed with the Batzal Yarok ("Green Onion") satirical theatre company, which also toured Israel.[2][9] Other members of the group included Uri Zohar, Nechama Hendel, Zaharira Harifai, Arik Einstein, and Oded Kotler.[10] In 1960, Topol co-founded the Haifa Municipal Theatre with Yosef Milo, serving as assistant to the director and acting in plays by Shakespeare, Ionesco, and Brecht.[2][11] In 1965 he performed in the Cameri Theatre in Tel Aviv.[11]

Early film career

Haim Topol, then a young man and of Ashkenazi heritage, plays the old Sephardic manipulator with such consummate skill that even aged immigrants from Morocco and Tunisia were convinced that he was one of them.

–Tom Tugend on Topol's portrayal of Sallah Shabati[12]

Topol's first film appearance was in the 1961 film I Like Mike, followed by the 1963 Israeli film El Dorado.[2][10] His breakthrough role came as the lead character in the 1964 film Sallah Shabati.[13] Adapted for the screen by Ephraim Kishon from his original play, the social satire depicts the hardships of a Sephardic immigrant family in the rough conditions of ma'abarot, immigrant absorption camps in Israel in the 1950s, satirizing "just about every pillar of Israeli society: the Ashkenazi establishment, the pedantic bureaucracy, corrupt political parties, rigid kibbutz ideologues and ... the Jewish National Fund's tree-planting program".[12][14] Topol, who was 29 during the filming,[15] was familiar playing the role of the family patriarch, having performed skits from the play with his Nahal entertainment troupe during his army years.[2][10] He contributed his own ideas for the part, playing the character as a more universal Mizrahi Jew instead of specifically a Yemenite, Iraqi, or Moroccan Jew, and asking Kishon to change the character's first name from Saadia (a recognizably Yemenite name) to Sallah (a more general Mizrahi name).[2]

The film won the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and Topol won the 1964 Golden Gate Award for Best Actor at the San Francisco International Film Festival and the 1965 Golden Globe for Most Promising Newcomer—Male,[2][9][10][16] alongside Harve Presnell and George Segal. Sallah Shabati was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, losing to the Italian-language Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow.[2]

In 1966, Topol made his English-language film debut as Abou Ibn Kaqden in the Mickey Marcus biopic Cast a Giant Shadow.[4][17]

Tevye the Dairyman

Topol came to greatest prominence in his portrayal of Tevye the Dairyman on stage and screen. He first played the lead role in the Israeli production of the musical Fiddler on the Roof in 1966,[10] replacing Shmuel Rodensky for 10 weeks when Rodensky fell ill.[2] Harold Prince, producer of the original Fiddler on the Roof that opened on Broadway in 1964, had seen Topol in Sallah Shabati and called him to audition for the role of the fifty-something Tevye in a new production scheduled to open at Her Majesty's Theatre in London on February 16, 1967.[18] Not yet fluent in English, Topol memorized the score from listening to the original Broadway cast album and practiced the lyrics with a British native.[18] When Topol arrived at the audition, Prince was surprised that this 30-year-old man had played Shabati, a character in his sixties. Topol explained, "A good actor can play an old man, a sad face, a happy man. Makeup is not an obstacle".[2] Topol also surprised the producers with his familiarity with the staging, since he had already acted in the Israeli production, and was hired.[2][19] He spent six months in London learning his part phonetically with vocal coach Cicely Berry.[19] Jerome Robbins, director and choreographer of the 1964 Broadway show who came over to direct the London production, "re-directed" the character of Tevye for Topol and helped the actor deliver a less caricatured performance.[20][21] Topol's performance received positive reviews.[21]

A few months after the opening, Topol was called up for reserve duty in the Six-Day War and returned to Israel. He was assigned to an army entertainment troupe on the Golan Heights.[21] Afterward he returned to the London production, appearing in a total of 430 performances.[22]

It was during the London run that he began being known by his last name only, as the English producers were unable to pronounce the voiceless uvular fricative consonant Ḥet at the beginning of his first name, Chaim, instead calling him "Shame".[2]

Chaim Topol breathed life into Tevye.

–Norman Jewison, 2011[23]

In casting the 1971 film version of Fiddler on the Roof, director Norman Jewison and his production team sought an actor other than Zero Mostel for the lead role. This decision was a controversial one, as Mostel had made the role famous in the long-running Broadway musical and wanted to star in the film.[24] But Jewison and his team felt Mostel would eclipse the character with his larger-than-life personality.[25][26][27] Jewison flew to London in February 1968 to see Topol perform as Tevye during his last week with the London production, and chose him over Danny Kaye, Herschel Bernardi, Rod Steiger, Danny Thomas, Walter Matthau, Richard Burton, and Frank Sinatra, who had also expressed interest in the part.[2][26][28]

Then 36 years old, Topol was made to look 20 years older and 30 pounds (14 kg) heavier with makeup and costuming.[5] As in his role as Shabati, Topol used the technique of "locking his muscles" to convincingly play an older character.[2][29] He later explained:

As a young man, I had to make sure that I didn't break the illusion for the audience. You have to tame yourself. I'm now someone who is supposed to be 50, 60 years old. I cannot jump. I cannot suddenly be young. You produce a certain sound [in your voice] that is not young.[2]

For his performance, Topol won the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy,[30] the Sant Jordi Award for Best Performance in a Foreign Film,[31] and the 1972 David di Donatello for Best Foreign Actor, sharing the latter with Elizabeth Taylor.[10] He was also nominated for the 1971 Academy Award for Best Actor, losing to Gene Hackman in The French Connection.[17][13]

In 1983 Topol reprised the role of Tevye in a revival of Fiddler on the Roof in West End theatre.[22] In 1989, he played the role in a 30-city U.S. touring production.[32] As he was by then the approximate age of the character, he commented, "I didn't have to spend the energy playing the age".[32] In 1990–1991, he again starred as Tevye in a Broadway revival of Fiddler at the Gershwin Theatre.[32][33] In 1991, he was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical,[34] losing to Jonathan Pryce in Miss Saigon. Topol again played Tevye in a 1994 London revival,[22] which became a touring production. In that production, the role of one of his daughters was played by his own daughter, Adi Topol Margalith.[2][35]

Topol reprised the role of Tevye for a 1997–1998 touring production in Israel, as well as a 1998 show at the Regent Theatre in Melbourne.[36] In September 2005 he returned to Australia for a Fiddler on the Roof revival at the Capitol Theatre in Sydney,[37] followed by an April 2006 production at the Lyric Theatre in Brisbane[38] and a June 2006 production at Her Majesty's Theatre in Melbourne.[36] In May 2007, he starred in a production in the Auckland Civic Theatre.[39]

On January 20, 2009, Topol began a farewell tour of Fiddler on the Roof as Tevye, opening in Wilmington, Delaware. He was forced to withdraw from the tour in Boston owing to a shoulder injury, and was replaced by Theodore Bikel and Harvey Fierstein, both of whom had portrayed Tevye on Broadway.[2] Topol estimated that he performed the role more than 3,500 times.[2][13][17]

In 2014, he appeared in Raising the Roof, a 50th anniversary tribute to Fiddler at New York City's Town Hall produced by National Yiddish Theatre. The evening featured Chita Rivera, Joshua Bell, Sheldon Harnick, Andrea Martin, Jerry Zaks, and more, and was co-directed by Gary John La Rosa and Erik Liberman.[40]

Other stage and film roles

In 1976, Topol played the lead role of the baker, Amiable, in the new musical The Baker's Wife, but was fired after eight months by producer David Merrick. In her autobiography, Patti LuPone, his co-star in the production, claimed that Topol had behaved unprofessionally on stage and had a strained relationship with her off-stage.[41] The show's composer, Stephen Schwartz, claimed that Topol's behavior greatly disturbed the cast and directors and resulted in the production not reaching Broadway as planned.[42] In 1988, Topol starred in the title role in Ziegfeld at the London Palladium.[11] He returned to the London stage in 2008 in the role of Honoré, played by Maurice Chevalier in the 1958 film Gigi.[2]

Topol appeared in more than 30 films in Israel and abroad.[17] Among his notable English-language appearances are the title role in Galileo (1975), Dr. Hans Zarkov in Flash Gordon (1980),[43] and Milos Columbo in the James Bond film For Your Eyes Only (1981).[43][44] He was said to be Israel's "only internationally-recognized entertainer" in the 1960s through 1980s.[2]

In Israel, Topol acted in and produced dozens of films and television series.[10] As a voice artist, he dubbed the voice of Bagheera in the Hebrew-language versions of The Jungle Book and the 2003 sequel as well as Rubeus Hagrid in the first two films of the Harry Potter film series.[17][13] He is also a playwright and screenwriter.[14]

He was featured on two BBC One programs, the six-part series Topol's Israel (1985) and earlier It's Topol (1968).[9][45] A Hebrew-language documentary of his life, Chaim Topol – Life as a Film, aired on Israel's Channel 1 in 2011, featuring interviews with his longtime actor friends in Israel and abroad.[7]

Musical recordings

A baritone,[7] Topol recorded several singles and albums, including film soundtracks, children's songs, and Israeli war songs. His albums include Topol With Roger Webb And His Orchestra - Topol '68 (1967), Topol Sings Israeli Freedom Songs (1967), War Songs By Topol (1968), and Topol's Israel (1984). He appeared on the soundtrack album for the film production of Fiddler on the Roof (1971), the London cast album (1967); and the television production of The Going Up Of David Lev (2010).[46]

Author and illustrator

His autobiography, Topol by Topol, was published in London by Weindenfel and Nicholson (1981).[9][36] He also authored To Life! (1994) and Topol's Treasury of Jewish Humor, Wit and Wisdom (1995).[36]

Topol has illustrated approximately 25 books in both Hebrew and English.[10] He has also produced drawings of Israeli national figures. His sketches of Israeli presidents were reproduced in a 2013 stamp series issued by the Israel Philatelic Federation,[10] as was his self-portrait as Tevye for a 2014 commemorative stamp marking the 50th anniversary of the Broadway debut of Fiddler on the Roof.[47]

Charitable work

In 1967, Topol founded Variety Israel, an organization serving children with special needs.[10][48] He is also a co-founder and chairman of the board of Jordan River Village, a year-round camp for Arab and Jewish children with life-threatening illnesses, which opened in 2012.[10][49]

Other awards

Topol was a recipient of Israel's Kinor David award in arts and entertainment in 1964.[50] He received a Best Actor award from the San Sebastián International Film Festival for his performance in the 1972 film Follow Me![10] In 2008, he was named an Outstanding Member of the Israel Festival for his contribution to Israeli culture.[10][51]

In 2014, the University of Haifa conferred upon Topol an honorary degree in recognition of his 50 years of activity in Israel's cultural and public life.[10] In 2015, he received the Israel Prize for lifetime achievement.[48][17]

Personal life

Topol married Galia Finkelstein in October 1956. They have one son and two daughters.[2] The couple resides in Galia's childhood home in Tel Aviv.[17] Topol's hobbies include sketching and sculpting.[2] In June 2022, Topol's son, Omer, revealed that his father suffers from Alzheimer's disease.[52]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | I Like Mike | Mikha | |

| 1962 | Etz O Palestina (The True Story of Palestine) | Narrator | |

| 1963 | El Dorado | Benny Sherman | Credited as Haim Topol |

| 1964 | Sallah Shabati | Sallah Shabati | Credited as Haym Topol. Golden Globe Award for Most Promising Newcomer – Male San Francisco International Film Festival Award for Best Actor |

| 1966 | Cast a Giant Shadow | Abou Ibn Kader | |

| 1967 | Ervinka | Ervinka | Credited as Haim Topol. Also co-producer. |

| 1968 | Kol Mamzer Melekh (Every Bastard a King) | Co-producer | |

| Ha-Shehuna Shelanu (Fish, Football, and Girls) | Co-producer | ||

| 1969 | Before Winter Comes | Janovic | |

| A Talent for Loving | General Molina | ||

| 1971 | Fiddler on the Roof | Tevye | David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Actor Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy Sant Jordi Award for Best Performance in a Foreign Film Nominated – Academy Award for Best Actor |

| The Going Up of David Lev | Chaim | TV movie | |

| Hatarnegol (The Boys Will Never Believe It; The Rooster) | Gadi Zur | Also co-producer | |

| 1972 | Follow Me! | Julian Cristoforou | San Sebastián International Film Festival award for Best Actor |

| 1975 | Galileo | Galileo Galilei | |

| 1979 | The House on Garibaldi Street | Michael | TV movie |

| 1980 | Flash Gordon | Dr. Hans Zarkov | |

| 1981 | For Your Eyes Only | Milos Columbo | |

| 1983 | The Winds of War | Berel Jastrow | TV miniseries |

| 1985 | Roman Behemshechim (Again, Forever) | Effi Avidar | |

| 1987 | Queenie | Dimitri Goldner | TV movie |

| 1988 | Tales of the Unexpected | Professor Max Kelada | Episode: Mr. Know-All |

| 1988–1989 | War and Remembrance | Berel Jastrow | TV miniseries, 11 episodes |

| 1993 | SeaQuest DSV | Dr. Rafik Hassan | Episode: Treasure of the Mind |

| 1998 | Left Luggage | Mr. Apfelschnitt | |

| Time Elevator | Shalem | ||

| 2000 | Inside For Your Eyes Only | Documentary | |

| 2001 | Fiddler on the Roof: 30 Years of Tradition | Documentary | |

| 2019 | Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles | Documentary |

References

- Monaco 1991, p. 537.

- Slater, Robert (February 6, 2013). "One More Fiddle for the Road". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Maltin 1994, p. 881.

- "Topol Film Reference biography". Filmreference.com. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Bonfante 1971, p. 90.

- Margit, Maya (May 1, 2017). "EXCLUSIVE: Fiddler on the Roof's Chaim Topol and his memories of Israeli independence". i24news. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- Kisri, Shulamit (February 10, 2011). "חיים טופול - החיים כמשחק" [Chaim Topol: Life as a Game]. News1 (in Hebrew). Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- Bial 2005, p. 80.

- Kronish & Safirman 2003, p. 215.

- "University of Haifa" (PDF). University of Haifa Board of Governors. May 27, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Hartnoll & Found 1996.

- Tugend, Tom (November 13, 1997). "Israeli Satire and Mystery". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Heller, Aron (April 21, 2015). "Iconic actor Chaim Topol reflects on long career". The Times of Israel. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- "Chaim Topol in conversation with Rivka Jacobson". Plays to See. September 17, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Weiler, A.H. (October 13, 1965). "'Sallah,' Comedy, Opens at Little Carnegie". The New York Times. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Franks 2004, p. 280.

- "Iconic Israeli actor Chaim Topol reflects upon his long career". Haaretz. Associated Press. April 21, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Isenberg 2014, p. 86.

- Isenberg 2014, p. 87.

- Lawrence 2001, p. 248.

- Isenberg 2014, p. 88.

- Isenberg 2014, p. 89.

- Isenberg 2014, p. 103.

- Isenberg 2014, pp. 103–104.

- Bial 2005, p. 78.

- Isenberg 2014, p. 102.

- Vogel 2003, p. 289.

- Bial 2005, pp. 78–79.

- Isenberg 2014, pp. 87–88.

- Franks 2004, p. 283.

- Cashman, Greer Fay (April 7, 2015). "Grapevine: Between the Negev and the Galilee". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- Shepard, Richard F. (November 18, 1990). "THEATER; Sunrise, Sunset". The New York Times. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- Dietz 2016, p. 33.

- Dietz 2016, p. 34.

- Isenberg 2014, p. 142.

- "Chaim Topol". AusStage. 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Nye, Monica (August 24, 2005). "Topol's Model Role". The Age. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Munro-Wallis, Nigel (April 7, 2006). "Fiddler on the Roof". ABC Radio Brisbane. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Manning, Selwyn (May 10, 2007). "Topol – Auckland Has In Its Midst A Champion". Scoop News. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Hetrick, Adam (June 2, 2014). "Chita Rivera, Karen Ziemba and More Join Fiddler on the Roof at Town Hall". Playbill. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- LuPone 2010, pp. 84–86.

- De Giere 2008, p. 121ff.

- Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 171.

- "For Your Eyes Only". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2013. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013.

- Hercombe, Peter (1984). "From Minefields to Massada". Pebble Mill News.

- "Topol". Discogs. 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- Estrin, Daniel (July 13, 2015). "Chaim Topol is still fiddling after all these years". Public Radio International. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- "Chaim Topol wins Israel Prize for lifetime achievement". Ynetnews. March 31, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Alster, Paul (April 7, 2013). "Chaim Topol Is More Than Tevye for Sick Jewish and Arab Children". The Forward. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- "D508-133.jpg". The National Photo Collection. 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- Yudelovitch, Merav (May 19, 2008). "חיים טופול יקיר פסטיבל ישראל" [Chaim Topol is a Notable of the Israel Festival]. Ynet (in Hebrew). Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- "עומר טופול: "אבא תמיד אמר לי, 'אם אגיע למצב כזה, תעזור לי למות'"". www.ynet.co.il (in Hebrew). June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

Sources

- Bial, Henry (2005). Acting Jewish: Negotiating Ethnicity on the American Stage & Screen. University of Michigan Press. p. 78. ISBN 047206908X.

- Bonfante, Jordan (December 3, 1971). "Topol: Fiddler on the Screen". LIFE. 71 (23).

- De Giere, Carol (2008). "The Baker's Wife: Mixed Ingredients". Defying Gravity: The Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz, from Godspell to Wicked. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. ISBN 978-1557837455.

- Holt, Patricia (December 7, 2010). "Patti LuPone: A ShowBiz Memoir to Remember". Holtuncensored.com.

- Dietz, Dan (2016). The Complete Book of 1990s Broadway Musicals. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442272149.

- Franks, Don (2004). Entertainment Awards: A Music, Cinema, Theatre and Broadcasting Guide, 1928 through 2003 (3rd ed.). McFarland. ISBN 0786417986.

- Hartnoll, Phyllis; Found, Peter (1996). The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192825742.

- Isenberg, Barbara (2014). Tradition!: The Highly Improbable, Ultimately Triumphant Broadway-to-Hollywood Story of Fiddler on the Roof, the World's Most Beloved Musical. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1466862524.

- Lawrence, Greg (2001). Dance with Demons: The Life of Jerome Robbins. Penguin. ISBN 1101204060.

- LuPone, Patti (2010). Patti LuPone: A Memoir. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 978-0307460752.

- Maltin, Leonard, ed. (1994). Leonard Maltin's Movie Encyclopedia. Dutton. ISBN 9780525936350.

- Monaco, James, ed. (1991). The Encyclopedia of Film. Perigee Books. p. 537. ISBN 0399516042.

- Smith, Jim; Lavington, Stephen (2002). Bond Films. Virgin. ISBN 0753507099.

- Kronish, Amy; Safirman, Costel (2003). Israeli Film: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313321442.

- Vogel, Frederick G. (2003). Hollywood Musicals Nominated for Best Picture. McFarland. ISBN 0786443421.

External links

- Chaim Topol at IMDb

- Chaim Topol at the Internet Broadway Database

- Chaim Topol at the TCM Movie Database

- Chaim Topol at AllMovie