Charles VIII of France

Charles VIII, called the Affable (French: l'Affable; 30 June 1470 – 7 April 1498), was King of France from 1483 to his death in 1498. He succeeded his father Louis XI at the age of 13.[1] His elder sister Anne acted as regent jointly with her husband Peter II, Duke of Bourbon[1][2] until 1491 when the young king turned 21 years of age. During Anne's regency, the great lords rebelled against royal centralisation efforts in a conflict known as the Mad War (1485–1488), which resulted in a victory for the royal government.

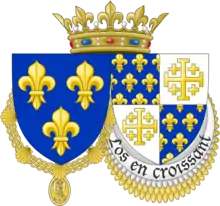

| Charles VIII | |

|---|---|

%252C_by_anonymous_artist%252C_16th_century_(cropped).jpg.webp) 16th-century portrait after Jean Perréal | |

| King of France (more...) | |

| Reign | 30 August 1483 – 7 April 1498 |

| Coronation | 30 May 1484 (Reims) |

| Predecessor | Louis XI |

| Successor | Louis XII |

| Regent | Anne of France and Peter II, Duke of Bourbon (1483–1491) |

| Born | 30 June 1470 Château d'Amboise, France |

| Died | 7 April 1498 (aged 27) Château d'Amboise, France |

| Burial | 1 May 1498 Saint Denis Basilica (body) Notre-Dame de Cléry Basilica, Cléry-Saint-André (heart) |

| Spouse | Anne, Duchess of Brittany

(m. 1491) |

| Issue among others... | Charles Orlando, Dauphin of France |

| House | Valois |

| Father | Louis XI, King of France |

| Mother | Charlotte of Savoy |

| Signature | .PNG.webp) |

In a remarkable stroke of audacity, Charles married Anne of Brittany in 1491 after she had already been married by proxy to the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I in a ceremony of questionable validity. Preoccupied by the problematic succession in the Kingdom of Hungary, Maximilian failed to press his claim. Upon his marriage, Charles became administrator of Brittany and established a personal union that enabled France to avoid total encirclement by Habsburg territories.

To secure his rights to the Neapolitan throne that René of Anjou had left to his father, Charles made a series of concessions to neighbouring monarchs and conquered the Italian peninsula without much opposition. A coalition formed against the French invasion of 1494–98 attempted to stop Charles' army at Fornovo, but failed and Charles marched his army back to France.

Charles died in 1498 after accidentally striking his head on the lintel of a door at the Château d'Amboise, his place of birth. Since he had no male heir, he was succeeded by his 2nd cousin once removed, Louis XII from the Orléans cadet branch of the House of Valois.

Youth

Charles was born at the Château d'Amboise in France, the only surviving son of King Louis XI by his second wife Charlotte of Savoy.[2] His godparents were Charles II, Duke of Bourbon (the godchild's namesake), Joan of Valois, Duchess of Bourbon, and the teenage Edward of Westminster, the son of Henry VI of England who had been living in France since the deposition of his father by Edward IV.[3] Charles succeeded to the throne on 30 August 1483 at the age of 13. His health was poor. He was regarded by his contemporaries as possessing a pleasant disposition, but also as foolish and unsuited for the business of the state. In accordance with the wishes of Louis XI, the regency of the kingdom was granted to Charles' elder sister Anne, a formidably intelligent and shrewd woman described by her father as "the least foolish woman in France."[4] She ruled as regent, together with her husband Peter of Bourbon, until 1491.

Marriage

Charles was betrothed on 22 July 1483 to the 3-year-old Margaret of Austria, daughter of the Archduke Maximilian of Austria (later Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I) and Mary, Duchess of Burgundy. The marriage was arranged by Louis XI, Maximilian, and the Estates of the Low Countries as part of the 1482 Peace of Arras between France and the Duchy of Burgundy. Margaret brought the counties of Artois and Burgundy to France as her dowry, and she was raised in the French court as a prospective queen.

In 1488, however, Francis II, Duke of Brittany, died in a riding accident, leaving his 11-year-old daughter Anne as his heir. Anne, who feared for the independence of her duchy against the ambitions of France, arranged a marriage in 1490 between herself and the widower Maximilian. The regent Anne of France and her husband Peter refused to countenance such a marriage, however, since it would place Maximilian and his family, the Habsburgs, on two French borders. The French army invaded Brittany, taking advantage of the preoccupation of Maximilian and his father, Emperor Frederick III, with the disputed succession to Mathias Corvinus, King of Hungary.[5] Anne of Brittany was forced to renounce Maximilian (whom she had only married by proxy) and agree to be married to Charles VIII instead.[6]

In December 1491, in an elaborate ceremony at the Château de Langeais, Charles and Anne of Brittany were married. The 14-year-old Duchess Anne, not happy with the arranged marriage, arrived for her wedding with her entourage carrying two beds. However, Charles's marriage brought him independence from his relatives and thereafter he managed affairs according to his own inclinations. Queen Anne lived at the Clos Lucé in Amboise.

There still remained the matter of Charles' first betrothed, the young Margaret of Austria. Although the cancellation of her betrothal meant that she by rights should have been returned to her family, Charles did not initially do so, intending to marry her usefully elsewhere in France. Eventually, in 1493, she was returned to her family, together with her dowry – though the Duchy of Burgundy was retained in the Treaty of Senlis.

Around the king there was a circle of court poets, the most memorable being the Italian humanist Publio Fausto Andrelini from Forlì, who spread Renaissance humanism in France. During a pilgrimage to pay respects to his father's remains, Charles observed Mont Aiguille and ordered Antoine de Ville to ascend to the summit in an early technical alpine climb, later alluded to by Rabelais.[7][8]

Italian War

To secure France against invasions, Charles made treaties with Maximilian I of Austria (the Treaty of Barcelona with Maximilian of Austria on 19 January 1493)[9] and England, (the Treaty of Étaples with England on 3 November 1492)[10] buying their neutrality with large concessions. The English monarch Henry VII had forced Charles to abandon his support for the pretender Perkin Warbeck by despatching an expedition which laid siege to Boulogne. He devoted France's resources to building up a large army, including one of Europe's first siege trains with artillery.

In 1489, Pope Innocent VIII (1484–1492), then being at odds with Ferdinand I of Naples, offered Naples to Charles, who had a vague claim to the Kingdom of Naples through his paternal grandmother, Marie of Anjou. Innocent's policy of meddling in the affairs of other Italian states[11] was continued by his successor, Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503), when the latter supported a plan for a carving out a new state in central Italy. The new state would have impacted on Milan more than any of the other states involved. Consequently, in 1493, Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, appealed for help to Charles VIII.[12] Charles then returned Perpignan to Ferdinand II of Aragon to free up forces for the invasion of Italy.[13] The next year in 1494, Milan faced an additional threat. On 25 January 1494, Ferdinand I, King of Naples, died unexpectedly.[14] His death made Alfonso II, king of Naples. Alfonso II laid claim to the Milanese duchy.[15] Alfonso II now urged Charles to take Milan militarily. Charles was also urged on in this adventure by his favorite courtier, Étienne de Vesc. Thus, Charles came to imagine himself capable of actually taking Naples, and invaded Italy.

In an event that was to prove a watershed in Italian history,[16] Charles invaded Italy with 25,000 men (including 8,000 Swiss mercenaries) in September 1494 and marched across the peninsula virtually unopposed. He arrived in Pavia on 21 October 1494 and entered Pisa on 8 November 1494.[17] The French army subdued Florence in passing on their way south. Reaching Naples on 22 February 1495,[18] the French Army took Naples without a pitched battle or siege; Alfonso was expelled, and Charles was crowned King of Naples.

There were those in the Republic of Florence who appreciated the presence of the French king and his Army. The famous friar Savonarola believed that King Charles VIII was God's tool to purify the corruption of Florence. He believed that once Charles had ousted the evil sinners of Florence, the city would become a center of morality. Thus, Florence was the appropriate place to restructure the Church. This situation would eventually spill over into another conflict between Pope Alexander VI, who despised the idea of having the king in northern Italy where the Pope feared the King of France would interfere with the Papal States,[19] and Savonarola, who called for the king's intervention. This conflict would eventually lead Savonarola to be suspected of heresy and to be executed by the State.

The speed and power of the French advance frightened the other Italian rulers, including the Pope and even Ludovico of Milan. They formed an anti-French coalition, the League of Venice on 31 March 1495. The formation of the League of Venice, which included the northern Italian states of Duchy of Milan, the Republic of Venice, the Duchy of Mantua, and the Republic of Florence in addition to the Kingdom of Spain, the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Naples, appeared to have trapped Charles in southern Italy and blocked his return to France. Charles would have to cross the territory of at least some of the League members to return home to France. At the Fornovo in July 1495, the League was unable to stop Charles from marching his army out of Italy.[20] The League lost 2,000 men to his 1,000 and, although Charles lost nearly all the booty of the campaign, the League was unable to stop him from crossing their territory on his way back to France. Meanwhile, Charles' remaining garrisons in Naples were quickly subdued by Aragonese forces sent by Ferdinand II of Aragon, ally of Alfonso on 6–7 July 1495.[21] Thus in the end, Charles VIII lost all the gains that he had made in Italy.

Over the next few years, Charles VIII tried to rebuild his army and resume the campaign, but he was hampered by the large debts incurred in 1494–95. He never succeeded in gaining anything substantive.

Death

Charles died in 1498, two and a half years after his retreat from Italy, as the result of an accident. While on his way to watch a game of jeu de paume (real tennis) in Amboise he struck his head on the lintel of a door.[22] At around 2:00 p.m., while returning from the game, he fell into a sudden coma and died nine hours later.[23]

Charles bequeathed a meagre legacy: he left France in debt and in disarray as a result of his ambition. However, his expedition did strengthen cultural ties to Italy, energizing French art and literature in the latter part of the Renaissance. Since his children predeceased him, Charles was the last of the elder branch of the House of Valois. Upon his death, the throne passed to his brother-in-law and second cousin once removed, Louis XII. Anne returned to Brittany and began taking steps to regain the independence of her duchy. In order to stymie these efforts, Louis XII had his 24-year childless marriage to Charles's sister, Joan, annulled and married Anne.[24]

Issue

The marriage with Anne resulted in the birth of six recorded children, who all died young:

- Charles Orland, Dauphin of France (11 October 1492 – 16 December 1495), died of the measles when three years old. Buried at Tours Cathedral.[25]: 125

- Francis (August 1493), was premature and stillborn. Buried at Notre-Dame de Cléry.[lower-alpha 1]

- Stillborn daughter (March 1495)[28]

- Charles, Dauphin of France (8 September 1496 – 2 October 1496). Buried at Tours Cathedral.[25]: 125

- Francis, Dauphin of France (July 1497). He died several hours after his birth. Buried at Tours Cathedral.[25]: 125

- Anne of France (20 March 1498). She died on the day of her birth at Château de Plessis-lez-Tours. Buried at Tours Cathedral.[25]: 125

Media

The 1671 English play Charles VIII of France by John Crowne depicts his reign.

Charles VIII's invasion of Italy and his relations with Pope Alexander VI are depicted in the novel The Sultan's Helmsman.

In the 2011 Showtime series The Borgias, Charles VIII is portrayed by French actor Michel Muller. In the 2011 French-German historical drama Borgia, Charles VIII is played by Simon Larvaron. The event of the king's death is depicted in the TV series Borgia with a small twist: in the episode, Charles himself plays a game of jeu de paume with Cesare Borgia and loses; while leaving the game, Charles strikes his head on the lintel of a door.

In the 2017 German-Austrian historical drama Maximilian (miniseries), a young Charles when he was Dauphin is portrayed by French actor Max Baissette de Malglaive. Made available by American cable network Starz in 2018.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Charles VIII of France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- First Italian War

- Louis III of France, another French king who died after hitting his head on a lintel

Notes

- A letter dated at Orléans 14 August 1493 from Francesco della Casa to Pietro de’ Medici records that the Queen “grossa di sette mesi” gave birth “in uno piccolo villaggio...Corsel” to “un figliuolo maschio”.[26] Balby de Vernon suggests that the child “a sûrement été enterré à Cléry” where a small child’s coffin was found.[27]

References

- Paul Murray Kendall, Louis XI: The Universal Spider (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1971), pp. 373–374.

- Stella Fletcher, The Longman Companion to Renaissance Europe, 1390–1530, (Routledge, 1999), 76.

- Desormeaux, Joseph-Louis Ripault (1776). Histoire de la maison de Bourbon, Tome II. Paris: Imprimerie royale. p. 249. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- Joni M. Hand, Women, Manuscripts and Identity in Northern Europe, 1350–1550, (Ashgate Publishing, 2013), 24.

- Tóth, Gábor Mihály (2008). "Trivulziana Cod. N. 1458: A New Testimony of the "Landus Report"" (PDF). Verbum Analecta Neolatina. X (1): 139–158. doi:10.1556/Verb.10.2008.1.9. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Hare, Christopher (1907). The high and puissant princess Marguerite of Austria, princess dowager of Spain, duchess dowager of Savoy, regent of the Netherlands. Harper & Brothers. pp. 43–44.

- "Histoire et Événements" (in French). p. Le Mont Aiguille – Supereminet invius. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- "L'ascension historique de 1492" [The historic ascent of 1492] (in French). Mont-Aiguille.com. 12 January 2009. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Michael Mallet and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559 (Harlow, England: Pearson Education, Limited, 2012) p. 32.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, (Harlow, England: Pearson Education, Limited, 2012) p. 13.

- Robert S. Hoyt and Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, Inc., 1976) pp. 618–619.

- Robert S. Hoyt and Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages, p. 619.

- Pigaillem 2008, p. 109.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian wars: 1494–1559, p. 14.

- Robert S. Hoyt and Stanely Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages, p. 619.

- Robert S. Hoyt, Europe in the Middle Ages, p. 619.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 20–21.

- R. Ritchie, Historical Atlas of the Renaissance, 64.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 11.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559 p. 31.

- Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, pp. 32–33.

- Heiner Gillmeister, Tennis: A Cultural History (London: Leicester University Press, 1998) p. 21. (ISBN 978-0718501471)

- Andrew R. Scoble, ed. (1856), The memoirs of Philip de Commines, volume 2, London: Henry G. Bohn, pp. 283–284

- Frederic J. Baumgartner, Louis XII (New York: St. Martin Press, 1996) p. 79.

- Anselme de Sainte-Marie, Père (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires.

- Desjardins, A. (1859). Négociations diplomatiques de la France avec la Toscane (Paris), Tome I, p. 245.

- Kerrebrouck, P. van (1990). Les Valois (Nouvelle histoire généalogique de l'auguste Maison de France) ISBN 9782950150929, p. 163 footnote 25, citing Balby de Vernon, Comte de (1873) Recherches historiques faites dans l’église de Cléry (Loiret) (Orléans), pp. 312–315.

- Fulin, R. (1883). La Spedizione di Carlo VIII in Italia raccontata da Marino Sanuto (Venezia), p. 250.

Sources

- Pigaillem, Henri (2008). Anne de Bretagne epouse de Charles VIII et de Louis XII. Pygmalion.