Charles VII of France

Charles VII (22 February 1403 – 22 July 1461), called the Victorious (French: le Victorieux)[1] or the Well-Served (le Bien-Servi), was King of France from 1422 to his death in 1461.

| Charles VII | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Jean Fouquet, tempera on wood, Louvre Museum, Paris, c. 1445–1450 | |

| King of France (more...) | |

| Reign | 21 October 1422 – 22 July 1461 |

| Coronation | 17 July 1429 |

| Predecessor | Charles VI |

| Successor | Louis XI |

| Born | 22 February 1403 Paris, France |

| Died | 22 July 1461 (aged 58) Mehun-sur-Yèvre, France |

| Burial | 7 August 1461 |

| Spouse | Marie of Anjou (m. 1422) |

| Issue Detail |

|

| House | Valois |

| Father | Charles VI of France |

| Mother | Isabeau of Bavaria |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Signature | |

In the midst of the Hundred Years' War, Charles VII inherited the throne of France under desperate circumstances. Forces of the Kingdom of England and the duke of Burgundy occupied Guyenne and northern France, including Paris, the most populous city, and Reims, the city in which French kings were traditionally crowned. In addition, his father, Charles VI, had disinherited him in 1420 and recognized Henry V of England and his heirs as the legitimate successors to the French crown. At the same time, a civil war raged in France between the Armagnacs (supporters of the House of Valois) and the Burgundian party (supporters of the House of Valois-Burgundy, which was allied to the English).

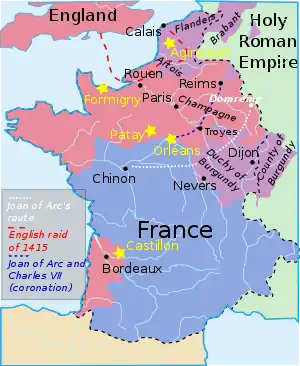

With his court removed to Bourges, south of the Loire River, Charles was disparagingly called the "King of Bourges", because the area around this city was one of the few remaining regions left to him. However, his political and military position improved dramatically with the emergence of Joan of Arc as a spiritual leader in France. Joan and other charismatic figures led French troops to lift the sieges of Orléans and other strategic cities on the Loire river, and to crush the English at the battle of Patay. With the local English troops dispersed, the people of Reims switched allegiance and opened their gates, which enabled the coronation of Charles VII at Reims Cathedral in 1429. Six years later, he ended the English-Burgundian alliance by signing the Treaty of Arras with Burgundy, followed by the recovery of Paris in 1436 and the steady reconquest of Normandy in the 1440s using a newly organized professional army and advanced siege cannons. Following the battle of Castillon in 1453, the French expelled the English from all their continental possessions except the Pale of Calais.

The last years of Charles VII were marked by conflicts with his turbulent son, the future Louis XI of France.

Early life

Born at the Hôtel Saint-Pol, the royal residence in Paris, Charles was given the title of Count of Ponthieu six months after his birth in 1403.[2] He was the eleventh child and fifth son of Charles VI of France and Isabeau of Bavaria.[1] His four elder brothers, Charles (1386), Charles (1392–1401), Louis (1397–1415) and John (1398–1417) had each held the title of Dauphin of France as heirs apparent to the French throne in turn.[1] All died childless, leaving Charles with a rich inheritance of titles.[1]

Dauphin

Almost immediately after becoming dauphin, Charles had to face threats to his inheritance, and he was forced to flee from Paris on 29 May 1418 after the partisans of John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, had entered the city the previous night.[3] By 1419, Charles had established his own court in Bourges and a Parlement in Poitiers.[3] On 11 July of that same year, Charles and John the Fearless attempted a reconciliation on a small bridge near Pouilly-le-Fort, not far from Melun where Charles was staying. They signed the Treaty of Pouilly-le-Fort in which they would share authority of the government, assist each other and not to form any treaties without the other’s consent.[4] Charles and John also decided that a further meeting should take place the following 10 September. On that date, they met on the bridge at Montereau.[5] The Duke assumed that the meeting would be entirely peaceful and diplomatic, thus he brought only a small escort with him. The Dauphin's men reacted to the Duke's arrival by attacking and killing him. Charles' level of involvement has remained uncertain to this day. Although he claimed to have been unaware of his men's intentions, this was considered unlikely by those who heard of the murder.[1] The assassination marked the end of any attempt of a reconciliation between the Armagnac and Burgundian factions, thus playing into the hands of Henry V of England. Charles was later required by a treaty with Philip the Good, the son of John the Fearless, to pay penance for the murder, which he never did.

Treaty of Troyes (1420)

At the death of his father, Charles VI, the succession was cast into doubt. The Treaty of Troyes, signed by Charles VI on 21 May 1420, mandated that the throne pass to the infant King Henry VI of England, the son of the recently deceased Henry V and Catherine of Valois, daughter of Charles VI; however, Frenchmen loyal to the king of France regarded the treaty as invalid on grounds of coercion and Charles VI's diminished mental capacity. For those who did not recognize the treaty and believed the Dauphin Charles to be of legitimate birth, he was considered to be the rightful heir to the throne. For those who did not recognize his legitimacy, the rightful heir was recognized as Charles, Duke of Orléans, cousin of the Dauphin, who was in English captivity. Only the supporters of Henry VI and the Dauphin Charles were able to enlist sufficient military force to press effectively for their candidates. The English, already in control of northern France, were able to enforce the claim of their king in the regions of France that they occupied. Northern France, including Paris, was thus ruled by an English regent, Henry V's brother, John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, based in Normandy (see Dual monarchy of England and France).

King of Bourges

In his adolescent years, Charles was noted for his bravery and flamboyant style of leadership. At one point after becoming Dauphin, he led an army against the English dressed in the red, white, and blue that represented his family; his heraldic device was a mailed fist clutching a naked sword. However, in July 1421, upon learning that Henry V was preparing to attack from Mantes with a much larger army, he withdrew from the siege of Chartres.[6] He then went south of the Loire River under the protection of Yolande of Aragon, known as "Queen of the Four Kingdoms" and, on 18 December 1422, married her daughter, Marie of Anjou,[7] to whom he had been engaged since December 1413 in a ceremony at the Louvre Palace.

Charles, unsurprisingly, claimed the title King of France for himself, but he failed to make any attempts to expel the English from northern France out of indecision and a sense of hopelessness[8] Instead, he remained south of the Loire River, where he was still able to exert power, and maintained an itinerant court in the Loire Valley at castles such as Chinon. He was still customarily known as "Dauphin," or derisively as "King of Bourges," after the town where he generally lived. Periodically, he considered flight to the Iberian Peninsula, which would have allowed the English to advance their occupation of France.

Siege of Orléans

Political conditions in France took a decisive turn in the year 1429 just as the prospects for the Dauphin began to look hopeless. The town of Orléans had been under siege since October 1428. The English regent, the Duke of Bedford (the uncle of Henry VI), was advancing into the Duchy of Bar, ruled by Charles's brother-in-law, René. The French lords and soldiers loyal to Charles were becoming increasingly desperate. Then in the little village of Domrémy, on the border of Lorraine and Champagne, a teenage girl named Joan of Arc (French: Jeanne d'Arc), demanded that the garrison commander at Vaucouleurs, Robert de Baudricourt, collect the soldiers and resources necessary to bring her to the Dauphin at Chinon,[9] stating that visions of angels and saints had given her a divine mission. Granted an escort of five veteran soldiers and a letter of referral to Charles by Lord Baudricourt, Joan rode to see Charles at Chinon. She arrived on 23 February 1429.[9]

Second-hand testimony by witnesses who were not present when Joan and the Dauphin met state Charles wanted to test her claim to be able to recognise him despite never having seen him, and so he disguised himself as one of his courtiers. He stood in their midst when Joan entered the chamber in which the court was assembled. Joan identified Charles immediately. She bowed low to him and embraced his knees, declaring "God give you a happy life, sweet King!" Despite attempts to claim that another man was in fact the king, Thereafter Joan referred to him as "Dauphin" or "Noble Dauphin" until he was crowned in Reims four months later. After a private conversation between the two, Charles became inspired and filled with confidence.

After her encounter with Charles in March 1429, Joan of Arc set out to lead the French forces at Orléans. She was aided by skilled commanders such as Étienne de Vignolles, known as La Hire, and Jean Poton de Xaintrailles. They compelled the English to lift the siege on 8 May 1429, thus turning the tide of the war. The French won the Battle of Patay on 18 June, at which the English field army lost about half its troops. After pushing further into English and Burgundian-controlled territory, Charles was crowned King Charles VII of France in Reims Cathedral on 17 July 1429.

Joan was later captured by Burgundian troops under John of Luxembourg at the siege of Compiègne on 24 May 1430.[10] The Burgundians handed her over to their English allies. Tried for heresy by a court composed of pro-English clergy such as Pierre Cauchon, who had long served the English occupation government,[11] she was burned at the stake on 30 May 1431.

French victory

Nearly as important as Joan of Arc in the cause of Charles was the support of the powerful and wealthy family of his wife Marie d'Anjou, particularly his mother-in-law, Queen Yolande of Aragon. But whatever affection he may have had for his wife, or whatever gratitude he may have felt for the support of her family, the great love of Charles VII's life was his mistress, Agnès Sorel.

Charles VII and Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, then signed the 1435 Treaty of Arras, by which the Burgundian faction rejected their English alliance and became reconciled with Charles VII, just as things were going badly for their English allies. With this accomplishment, Charles attained the essential goal of ensuring that no Prince of the Blood recognised Henry VI as King of France.[12]

Over the following two decades, the French recaptured Paris from the English and eventually recovered all of France with the exception of the northern port of Calais.

Close of reign

Charles' later years were marked by hostile relations with his heir, Louis, who demanded real power to accompany his position as the Dauphin. Charles consistently refused him. Accordingly, Louis stirred up dissent and fomented plots in attempts to destabilise his father's reign. He quarrelled with his father's mistress, Agnès Sorel, and on one occasion drove her with a bared sword into Charles' bed, according to one source. Eventually, in 1446, after Charles' last son, also named Charles, was born, the king banished the Dauphin to the Dauphiny. The two never met again. Louis thereafter refused the king's demands to return to court, and he eventually fled to the protection of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1456.

In 1458, Charles became ill. A sore on his leg (an early symptom, perhaps, of diabetes or another condition) refused to heal, and the infection in it caused a serious fever. The king summoned Louis to him from his exile in Burgundy, but the Dauphin refused to come. He employed astrologers to foretell the exact hour of his father's death. The king lingered on for the next two and a half years, increasingly ill, but unwilling to die. During this time he also had to deal with the case of his rebellious vassal John V of Armagnac.

Finally, however, there came a point in July 1461 when the king's physicians concluded that Charles would not live past August. Ill and weary, the king became delirious, convinced that he was surrounded by traitors loyal only to his son. Under the pressure of sickness and fever, he went mad. By now another infection in his jaw had caused an abscess in his mouth. The swelling caused by this became so large that, for the last week of his life, Charles was unable to swallow food or water. Although he asked the Dauphin to come to his deathbed, Louis refused, instead waiting at Avesnes, in Burgundy, for his father to die. At Mehun-sur-Yèvre, attended by his younger son, Charles, and aware of his elder son's final betrayal, the King starved to death. He died on 22 July 1461, and was buried, at his request, beside his parents in Saint-Denis.

Charles VII Royal d'or.

Charles VII Royal d'or. Charles VII Ecu neuf, 1436.

Charles VII Ecu neuf, 1436. Charles VII on a Franc à cheval from 1422–23.

Charles VII on a Franc à cheval from 1422–23.

Legacy

Although Charles VII's legacy is far overshadowed by the deeds and eventual martyrdom of Joan of Arc and his early reign was at times marked by indecisiveness and inaction, he was responsible for successes unprecedented in the history of the Kingdom of France. He succeeded in what four generations of his predecessors (namely his father Charles VI, his grandfather Charles V, his great-grandfather John II and great-great grandfather Philip VI) failed to do — the expulsion of the English and the conclusion of the Hundred Years' War.

He had created France's first standing army since Roman times. In The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli asserts that if his son Louis XI had continued this policy, then the French would have become invincible.

Charles VII secured himself against papal power by the Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges. He also established the University of Poitiers in 1432, and his policies brought some economic prosperity to his subjects.

Family

Children

Charles married his second cousin Marie of Anjou on 18 December 1422.[13] They were both great-grandchildren of King John II of France and his first wife Bonne of Bohemia through the male line. They had fourteen children:

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Louis | 3 July 1423 | 30 August 1483 | King of France. Married firstly Margaret of Scotland, no issue.[14] Married secondly Charlotte of Savoy, had issue.[14] |

| John | 19 September 1426 | Lived for a few hours. | |

| Radegonde | 1425[15] or August 1428[16] | February 1445[lower-alpha 1][17] | Betrothed to Sigismund, Archduke of Austria,[17] on 22 July 1430. |

| Catherine | 1428[16] | 13 September 1446 | Married Charles the Bold.[14] |

| James | 1432 | 2 March 1437 | Died aged five. |

| Yolande | 23 September 1434 | 23/29 August 1478 | Married Amadeus IX, Duke of Savoy, had issue. |

| Joan | 4 May 1435 | 4 May 1482 | Married John II, Duke of Bourbon, no issue. |

| Philip | 4 February 1436 | 11 June 1436 | Died in infancy. |

| Margaret | May 1437 | 24 July 1438 | Died aged one. |

| Joanna | 7 September 1438 | 26 December 1446 | Twin of Marie, died aged eight. |

| Marie | 7 September 1438 | 14 February 1439 | Twin of Joanna, died in infancy. |

| Isabella | 1441 | Died young. | |

| Magdalena | 1 December 1443 | 21 January 1495 | Married Gaston of Foix, Prince of Viana.[18] |

| Charles | 12 December 1446 | 24 May 1472 | Died without legitimate issue. |

Mistresses

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Charles VII of France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sources

- Allmand, Christopher (2014). Henry V. Yale University Press.

- Ashdown-Hill, John (2016). The Private Life of Edward IV. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445652450.

- Debris, Cyrille (2005). "Tu Felix Austria, nube" la dynastie de Habsbourg et sa politique matrimoniale à la fin du Moyen Age (XIIIe-XVIe siècles) (in French). Brepols.

- Fletcher, Stella (2013). The Longman Companion to Renaissance Europe, 1390-1530. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138165328.

- Hanawalt, Barbara (1998). The Middle Ages: An Illustrated History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510359-9.

- Taylor, Aline (2001). Isabel of Burgundy: The Duchess who played Politics in the Age of Joan of Arc, 1397–1471. Madison Books. ISBN 1-56833-227-0.

- Pernoud, R.; Clin, M. (1999). Joan of Arc: her story. Translated by Jeremy Adams. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-22730-2.

- Vale, M. (1 October 1974). Charles VII. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02787-9.

- Wagner, J. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War (PDF). Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2018.

- Ward, A.W.; Prothero, G.W.; Leathes, Stanley, eds. (1934). The Cambridge Modern History. Cambridge at the University Press.

- Watanabe, Morimichi (2011). Christianson, Gerald; Izbicki, Thomas M. (eds.). Nicholas of Cusa: A Companion to his Life and his Times. Ashgate Publishing.

- Wylie, James Hamilton (1914). The Reign of Henry the Fifth: 1413-1415. Cambridge University Press.

Notes

- Watanabe states Radegonde died at 19.[17]

References

- Wagner 2006, p. 89.

- Wylie 1914, p. 441.

- Richard Vaughan, John the Fearless: The Growth of Burgundian Power, Vol. 2, (Boydell Press, 2005), 263.

- Allmand 2014, p. 133-135.

- Richard Vaughan, John the Fearless: The Growth of Burgundian Power, 274.

- J. C. L. Sismonde de Sismondi, Histoire des Français, Volume XII, Paris, 1828, pp.611–312 (French)

- Taylor, Larissa Juliet (2009). The Virgin Warrior: The Life and Death of Joan of Arc. Yale University Press. p. 230.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. (1985). Joan of Arc. New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0877545569.

- Vale 1974, p. 46.

- Pernoud & Clin 1999, p. 88.

- Pernoud & Clin 1999, pp. 103–137, 209.

- Brady, Thomas A. (1994). Handbook of European History 1400–1600. Vol. 2. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 373.

- Ashdown-Hill 2016, p. xxiv.

- Ward, Prothero & Leathes 1934, p. table 22.

- Debris 2005, p. 361.

- Ashdown-Hill 2016, p. xxviii.

- Watanabe 2011, p. 105.

- Fletcher 2013, p. 81.

- Monks, Peter Rolf (1990). The Brussels Horloge de Sapience: Iconography and Text of Brussels. Brill. p. 10. ISBN 978-9004090880.

- Vale 1974, p. 92.

- Wellman, Kathleen (2013). Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France. Yale University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0300178852.

- Monks, Peter Rolf (1990). The Brussels Horloge de Sapience: Iconography and Text of Brussels. Brill. p. 11. ISBN 978-9004090880.

Further reading

- Lanhers, Yvonne (20 July 1998). "Charles VII, king of France". Encyclopædia Britannica (online).

External links

Beach, C, ed. (1914). "Charles VII, king of France". The New Student's Reference Work. 1. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

Beach, C, ed. (1914). "Charles VII, king of France". The New Student's Reference Work. 1. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co. Chisholm, H, ed. (1911). "Charles VII (1403–1461), king of France". Encyclopædia Britannica 11th ed. 5. Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, H, ed. (1911). "Charles VII (1403–1461), king of France". Encyclopædia Britannica 11th ed. 5. Cambridge University Press.