Chinese space program

The space program of the People's Republic of China is directed by the China National Space Administration (CNSA). China's space program has overseen the development and launch of ballistic missiles, thousands of artificial satellites, manned spaceflight, an indigenous space station, and has stated plans to explore the Moon, Mars, and the broader Solar System.[1][2][3]

|

| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

|

| By subject |

|

| By era |

The technological roots of the Chinese space program trace back to the 1950s, when, with the help of the newly-allied Soviet Union, China began development of its first ballistic missile and rocket programs in response to the perceived American (and, later, Soviet) threats.[4] Driven by the successes of Soviet Sputnik 1 and American Explorer 1 satellite launches in 1957 and 1958 respectively, China would launch its first satellite, Dong Fang Hong 1 in April of 1970 aboard a Long March 1 rocket making it the fifth nation to place a satellite in orbit.[5][6] A year later, China began development on a crewed space mission but, under pressure from Mao's Cultural Revolution on academics, was shut down and resources put to China's first reconnaissance satellite program, Fanhui Shi Weixing, which had its maiden launch in November 1975.[7][8] Chinese first crewed space program began in earnest several decades later, when an accelerated program of technological development culminated in Yang Liwei's successful 2003 flight aboard Shenzhou 5.[9][10] This achievement made China the third country to independently send humans into space.[11][12]

Today, the Chinese space program is statedly pursuing multiple sample-return missions and a manned mission to the Moon, space transportation, in-orbit maintenance of spacecraft, counterspace capabilities, quantum communications, orbiter and sample-return missions to Mars, and exploration missions throughout the Solar System and deep space.[3][13][14]

History

Early years

After the launch of mankind's first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, Mao Zedong decided during the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party on May 17, 1958, to make China an equal with the superpowers (Chinese: "我们也要搞人造卫星"; lit. 'We too need satellites'), by adopting Project 581 with the objective of placing a satellite in orbit by 1959 to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the PRC's founding.[15] This goal would be achieved in three phases: developing sounding rockets first, then launching small satellites, and in the final phase, large satellites.

During the cordial Sino-Soviet relations of the 1950s, the Soviet Union (USSR) had engaged in a cooperative technology transfer program with China, which helped kick-start the Chinese space program. However, the friendly relationship between the two countries soon turned to confrontation due to ideological differences in Marxism. As a consequence, all Soviet technological assistance was abruptly withdrawn after the 1960 Sino-Soviet split, and Chinese scientists continued on the program with extremely limited resources and knowledge.[16]

The first successful launch and recovery of a T-7A(S1) sounding rocket carrying a biological experiment (transporting eight white mice) was on July 19, 1964, from Base 603 (六〇三基地).[17] As the space race between the two superpowers reached its climax with the conquest of the Moon, Mao and Zhou Enlai decided on July 14, 1967, that the PRC should not be left behind, and started China's own crewed space program.[18] China's first spacecraft designed for human occupancy was named Shuguang-1 (曙光一号) in January 1968.[19] China's Space Medical Institute (航天医学工程研究所) was founded on April 1, 1968, and the Central Military Commission issued the order to start the selection of astronauts. As part of the "third line" effort to relocate critical defense infrastructure to the relatively remote interior (away from the Soviet border), it was decided to construct a new space center in the mountainous region of Xichang in the Sichuan province, code-named Base 27.

In August 1969, the development of China's first heavy-lift satellite launch vehicle (SLV), the Feng Bao 1 (FB-1, 风暴一号), was started by Shanghai's 2nd Bureau of Mechanic-Electrical Industry. The all-liquid two-stage launcher was derived from the DF-5 ICBM. Only a few months later, a parallel heavy-lift SLV program, also based on the same DF-5 ICBM and known as CZ-2, was started in Beijing by the First Space Academy. The DF-4 was used to develop the Long March-1 SLV. A newly designed spin-up orbital insertion solid-propellant rocket motor third stage was added to the two existing Nitric acid/UDMH liquid propellant stages. An attempt to use this vehicle to launch a Chinese satellite before Japan's first attempt ended in failure on November 16, 1969.[20]

The second satellite launch attempt on April 24, 1970, was successful. A CZ-1 was used to launch the 173 kg Dong Fang Hong I (东方红一号, meaning The East Is Red I), also known as Mao-1. It was the heaviest first satellite placed into orbit by a nation, exceeding the combined masses of the first satellites of the other four previous countries. The third stage of the CZ-1 was specially equipped with a 40 m2 solar reflector (观察球) deployed by the centrifugal force developed by the spin-up orbital insertion solid propellant stage. Therefore, the faint magnitude 5 to 8 brightness of the DFH-1 made the satellite (at best) barely visible with naked eyes was consequently dramatically increased to a comfortable magnitude 2 to 3. The PRC's second satellite was launched with the last of the CZ-1 SLVs on March 3, 1971. The 221 kg ShiJian-1 (SJ-1) was equipped with a magnetometer and cosmic-ray/x-ray detectors.

The first crewed space program, known as Project 714, was officially adopted in April 1971 with the goal of sending two astronauts into space by 1973 aboard the Shuguang spacecraft. The first screening process for astronauts had already ended on March 15, 1971, with 19 astronauts chosen. The program would soon be canceled due to political turmoil. The first flight test of the DF-5 ICBM was carried out in October 1971. On August 10, 1972, the new heavy-lift SLV FB-1 made its maiden test flight, with only partial success. The CZ-2A launcher, originally designed to carry the Shuguang-1 spacecraft, was first tested on November 5, 1974, carrying China's first FSW-0 recoverable satellite, but failed. After some redesign work, the modified CZ-2C successfully launched the FSW-0 No.1 recoverable satellite (返回式卫星) into orbit on November 26, 1975. After expansion, the Northern Missile Test Site was upgraded as a test base in January 1976 to become the Northern Missile Test Base (华北导弹试验基地) known as Base 25.

1970s to 1990s

After Mao died on September 9, 1976, his rival, Deng Xiaoping, denounced during the Cultural Revolution as reactionary and therefore forced to retire from all his offices, slowly re-emerged as China's new leader in 1978. At first, the new development was slowed. Then, several key projects deemed unnecessary were simply cancelled—the Fanji ABM system, the Xianfeng Anti-Missile Super Gun, the ICBM Early Warning Network 7010 Tracking Radar and the land-based high-power anti-missile laser program. Nevertheless, some development did proceed. The first Yuanwang-class space tracking ship was commissioned in 1979. The first full-range test of the DF-5 ICBM was conducted on May 18, 1980. The payload reached its target located 9300 km away in the South Pacific (7°0′S 117°33′E) and retrieved five minutes later by helicopter. Further development of the Long March rocket series allowed the PRC to initiate a commercial launch program in 1985, which has since launched more than 50 foreign satellites, primarily for European, African and Asian interests.[21]

The next crewed space program was even more ambitious and proposed in March 1986, as Astronautics plan 863-2. This consisted of a crewed spacecraft (Project 863-204) used to ferry astronaut crews to a space station (Project 863-205). Several spaceplane designs were rejected two years later and a simpler space capsule was chosen instead.[22] Although the project did not achieve its goals, it would ultimately evolve into the 1992 Project 921. The Ministry of Aerospace Industry was founded on July 5, 1988. On September 15, 1988, a JL-1 SLBM was launched from a Type 092 submarine. The maximum range of the SLBM is 2150 km.

Along Deng's policy of capitalist reforms in the Chinese economy, Chinese culture also changed. Therefore, names used in the space program, previously all chosen from the revolutionary history of the PRC, were soon replaced with mystical-religious ones. Thus, new Long March carrier rockets were renamed Divine Arrow (神箭),[23][24] spacecraft Divine Vessel (神舟),[25] space plane Divine Dragon (神龙),[26] land-based high-power laser Divine Light (神光)[27] and supercomputer Divine Might (神威).[28]

The Chinese human spaceflight program, namely the China Manned Space Program, was formally approved on September 21, 1992, by the Standing Committee of Politburo as Project 921,[29] with work beginning on 1 January 1993.

Following the fall of the Soviet Union, the cooperation between Russia and China restarted in the early 1990s. In 1994, China purchased Russian aerospace technology to further develop manned spaceflight capability. In 1995, a deal was signed between the two countries for the transfer of Russian Soyuz spacecraft technology to China. Included in the agreement were schedules for astronaut training, provision of Soyuz capsules, life support systems, docking systems, and space suits. In 1996, two Chinese astronauts, Wu Jie and Li Qinglong, began training at the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Russia. After training, these men returned to China and proceeded to train other Chinese astronauts at sites near Beijing and Jiuquan.[16]

In June 1993, the China Aerospace Corporation was founded in Beijing. It was also granted the title of China National Space Administration (CNSA).[30] On February 15, 1996, during the flight of the first Long March 3B heavy carrier rocket carrying Intelsat 708, the rocket veered off course immediately after clearing the launch platform, crashing 22 seconds later. It crashed 1.85 km (1.15 mi) away from the launch pad into a nearby mountain village.

In March 1998, the administrative branch of China Aerospace Corporation was split and then merged into the newly founded Commission for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense while retaining the title of CNSA. In the same year, Shenzhou spacecraft, loosely translatable as "divine vessel", completed construction. New launch facilities were built at the Jiuquan launch site in Inner Mongolia, and in the spring of 1998, a mock-up of the Long March 2F launch vehicle with Shenzhou spacecraft was rolled out for integration and facility tests.[16]

On July 1, 1999, the China Aerospace Corporation was converted into China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC).[30] In November 1999, after the 50th anniversary of the PRC's founding, China launched the Shenzhou 1 spacecraft and recovered it after a flight of 21 hours. It was the first uncrewed human spaceflight test conducted by China.

21st century

.JPG.webp)

Since the beginning of 21st century, China has been experiencing rapid economic growth, which led to higher investment into space programs and multiple major achievements in the following decades. The first satellite of BeiDou-1, the experimental regional navigation system of China, was launched on October 31, 2000, as China began to built its own satellite navigation system as an alternative to GPS.

In early 2000s, the Chinese manned space program continued to engage with Russia in technological exchanges regarding the development of a docking mechanism used for space stations.[31] Deputy Chief Designer, Huang Weifen, stated that near the end of 2009, China Manned Space Agency began to train astronauts on how to dock spacecraft.[32]

On October 15, 2003, astronaut Yang Liwei was put into space aboard Shenzhou 5 spacecraft by a Long March 2F rocket for more than 21 hours. China became the third country capable of conducting independent human spaceflight.

Around the same time, China began the preparation of extraterrestrial exploration, starting with the Moon. The Chinese Moon orbiting program was approved in January 2004[33] and was later transformed into Chinese Lunar Exploration Program. The first lunar orbiter Chang'e 1 was successfully launched on October 24, 2007, and was inserted into Moon orbit on November 7, making China the fifth nation to successfully orbit the Moon.

In March 2008, CNSA, along with the Commission for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense, was merged into the newly formed Ministry of Industry and Information Technology.

On September 27, 2008, two crew members of the Shenzhou 7 carried out China's first EVA. Three years later, on September 29, 2011, China launched Tiangong-1, the first prototype of Chinese space station module. The following Shenzhou 8, Shenzhou 9 and Shenzhou 10 missions proved that China had developed critical human spaceflight capabilities like space docking and berthing.

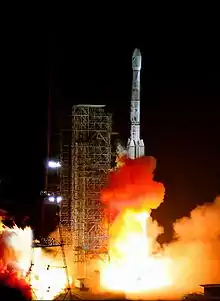

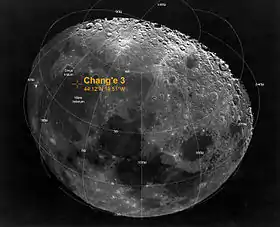

China began its first interplanetary exploration attempt in 2011 by sending Yinghuo-1, a Mars orbiter, in a joint mission with Russia. Yet it failed to leave Earth orbit due to the failure of Russian launch vehicle.[34] China then turned its focus back to the Moon by attempting the challenging lunar soft landing. On December 14, 2013, China successfully landed Chang'e 3 Moon lander and its rover Yutu on the Moon surface. It made China the third country in the world capable of performing lunar soft landing, just after USSR and the United States.

In 2016, Tiangong-2 and Shenzhou 11 were launched into Low Earth orbit. A 33-day crewed spaceflight mission proved that China was ready for a long-term space station built and maintained by its own.

In 2018, China performed more orbital launches than any other country on the planet for the first time in history.[35]

On January 3, 2019, Chang'e 4 conducted the first-ever soft landing on the far side of the Moon by any country, followed by 2020's Chang'e 5, a complex and successful lunar sample return mission, marking the completion of the three goals (orbiting, landing, returning) of the first stage of the lunar exploration program.

On June 23, 2020, the final satellite of Beidou was successfully launched by a Long March 3B rocket.[36] On July 31, 2020, Chinese leader Xi Jinping formally announced the commissioning of BeiDou Navigation Satellite System.[37]

On April 29, 2021, Tianhe, the 22-tonne core module of Tiangong space station, was successfully launched into Low Earth orbit by a Long March 5B rocket,[38] indicating the beginning of the construction of the Chinese Space Station.

Ever since the failure of Yinghuo-1, the Chinese space agency had embarked on its independent Mars mission. On July 23, 2020, China launched Tianwen-1, which included an orbiter, a lander, and a rover, on a Long March 5 rocket to Mars.[39] The Tianwen-1 was inserted into Mars orbit in February 2021 after a six-month journey, followed by a successful soft landing of the lander and Zhurong rover on May 14, 2021,[40] making China the third nation to both land softly on and establish communication from the Martian surface, after the Soviet Union and the United States.

On April 24, 2022, a rocket was launched on high altitude zero-pressure helium balloon from Lenghu in the northwest China's Qinghai Province,[41] which saves fuel and reduces overall costs.

Chinese space program and the international community

Dual-use technologies and outer space

The PRC is a member of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and a signatory to all United Nations treaties and conventions on space, with the exception of the 1979 Moon Treaty.[42] The United States government has long been resistant to the use of PRC launch services by American industry due to concerns over alleged civilian technology transfer that could have dual-use military applications to countries such as North Korea, Iran or Syria. Thus, financial retaliatory measures have been taken on many occasions against several Chinese space companies.[43]

NASA's policy excluding Chinese state affiliates

Due to security concerns, all researchers from the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) are prohibited from working with Chinese citizens affiliated with a Chinese state enterprise or entity.[44] In April 2011, the 112th United States Congress banned NASA from using its funds to host Chinese visitors at NASA facilities.[45] In March 2013, the U.S. Congress passed legislation barring Chinese nationals from entering NASA facilities without a waiver from NASA.[44]

The history of the U.S. exclusion policy can be traced back to allegations by a 1998 U.S. Congressional Commission that the technical information that American companies provided China for its commercial satellite ended up improving Chinese intercontinental ballistic missile technology.[46] This was further aggravated in 2007 when China blew up a defunct meteorological satellite in low Earth orbit to test a ground-based anti-satellite (ASAT) missile. The debris created by the explosion contributed to the space junk that litter Earth's orbit, exposing other nations' space assets to the risk of accidental collision.[46] The United States also fears the Chinese application of dual-use space technology for nefarious purposes.[47] The U.S. imposed an embargo to the U.S. - China space cooperation throughout the 2000s and by 2011, a clause inserted by then-Congressman Frank Wolf in the 2011 U.S. federal budget forbids NASA from hosting or participating in a joint scientific activity with China.

The Chinese response to the exclusion policy involved its own space policy of opening up its space station to the outside world, welcoming scientists coming from all countries.[47] American scientists have also boycotted NASA conferences due to its rejection of Chinese nationals in these events.[48]

Organization

Initially, the space program of the PRC was organized under the People's Liberation Army, particularly the Second Artillery Corps (now the PLA Rocket Force, PLARF). In the 1990s, the PRC reorganized the space program as part of a general reorganization of the defense industry to make it resemble Western defense procurement.

The China National Space Administration, an agency within the Commission of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense currently headed by Zhang Kejian, is now responsible for launches. The Long March rocket is produced by the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology, and satellites are produced by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. The latter organizations are state-owned enterprises; however, it is the intent of the PRC government that they should not be actively state-managed and that they should behave as independent design bureaus.

Universities and institutes

The space program also has close links with:

- College of Aerospace Science and Engineering, National University of Defense Technology

- School of Astronautics, Beihang University

- School of Aerospace, Tsinghua University

- School of Astronautics, Northwestern Polytechnical University

- School of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Zhejiang University

- Institute of Aerospace Science and Technology, Shanghai Jiaotong University

- College of Aeronautics, Harbin Institute of Technology

- School of Automation Science and Electrical Engineering, Beihang University

Space cities

- Dongfeng Space City (东风航天城), also known as Base 20 (二十基地) or Dongfeng base (东风基地)[49]

- Beijing Space City (北京航天城)

- Wenchang Space City (文昌航天城)

- Shanghai Space City (上海航天城)

- Yantai Space City (烟台航天城)[50][51]

- Guizhou Aerospace Industrial Park (贵州航天高新技术产业园), also known as Base 061 (航天〇六一基地), founded in 2002 after approval of Project 863 for industrialization of aerospace research centers (国家863计划成果产业化基地).[52]

Suborbital launch sites

- Nanhui (南汇县老港镇东进村) First successful launch of a T-7M sounding rocket on February 19, 1960.[53]

- Base 603 (安徽广德誓节渡中国科学院六〇三基地) Also known as Guangde Launch Site (广德发射场).[54] The first successful flight of a biological experimental sounding rocket transporting eight white mice was launched and recovered on July 19, 1964.[55]

Satellite launch centers

The PRC operates 4 satellite launch centers/sites:

- Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center (JSLC)

- Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center (TSLC)

- Xichang Satellite Launch Center (XSLC)

- Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site (administered by Xichang SLC)

Monitoring and control centers

- Beijing Aerospace Command and Control Center (BACCC)

- Xi'an Satellite Control Center (XSCC) also known as Base 26(二十六基地)

- Fleet of six Yuanwang-class space tracking ships.[56]

- Data relay satellite (数据中继卫星) Tianlian I (天链一号), specially developed to decrease the communication time between the Shenzhou 7 spaceship and the ground; it will also improve the amount of data that can be transferred. The current orbit coverage of 12 percent will thus be increased to a total of about 60 percent.[57][58]

- Deep Space Tracking Network composed with radio antennas in Beijing, Shanghai, Kunming and Urumuqi, forming a 3000 km VLBI (甚长基线干涉).[59]

Domestic tracking stations

- New integrated land-based space monitoring and control network stations, forming a large triangle with Kashi in the north-west of China, Jiamusi in the north-east and Sanya in the south.[60]

- Weinan Station

- Changchun Station

- Qingdao Station

- Zhanyi Station

- Nanhai Station

- Tianshan Station

- Xiamen Station

- Lushan Station

- Jiamusi Station

- Dongfeng Station

- Hetian Station

Overseas tracking stations

- Tarawa Station, Kiribati (dismantled in 2003[61])

- Malindi Station, Kenya

- Swakopmund tracking station, Namibia

- China Satellite Launch and Tracking Control General tracking hub at Espacio Lejano Station in Neuquén Province, Argentina.[62] 38.193014°S 70.147581°W

Plus shared space tracking facilities with France, Brazil, Sweden, and Australia.

Crewed landing sites

- Siziwang Banner

Notable spaceflight programs

Project 714

As the Space Race between the two superpowers reached its climax with humans landing on the Moon, Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai decided on July 14, 1967, that the PRC should not be left behind, and therefore initiated China's own crewed space program. The top-secret Project 714 aimed to put two people into space by 1973 with the Shuguang spacecraft. Nineteen PLAAF pilots were selected for this goal in March 1971. The Shuguang-1 spacecraft to be launched with the CZ-2A rocket was designed to carry a crew of two. The program was officially cancelled on May 13, 1972, for economic reasons, though the internal politics of the Cultural Revolution likely motivated the closure.

The short-lived second crewed program was based on the successful implementation of landing technology (third in the World after USSR and United States) by FSW satellites. It was announced a few times in 1978 with the open publishing of some details including photos, but then was abruptly canceled in 1980. It has been argued that the second crewed program was created solely for propaganda purposes, and was never intended to produce results.[63]

Project 863

A new crewed space program was proposed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences in March 1986, as Astronautics plan 863-2. This consisted of a crewed spacecraft (Project 863-204) used to ferry astronaut crews to a space station (Project 863-205). In September of that year, astronauts in training were presented by the Chinese media. The various proposed crewed spacecraft were mostly spaceplanes. Project 863 ultimately evolved into the 1992 Project 921.

Spacecraft

In 1992, authorization and funding was given for the first phase of Project 921, which was a plan to launch a crewed spacecraft. The Shenzhou program had four uncrewed test flights and two crewed missions. The first one was Shenzhou 1 on November 20, 1999. On January 9, 2001 Shenzhou 2 launched carrying test animals. Shenzhou 3 and Shenzhou 4 were launched in 2002, carrying test dummies. Following these was the successful Shenzhou 5, China's first crewed mission in space on October 15, 2003, which carried Yang Liwei in orbit for 21 hours and made China the third nation to launch a human into orbit. Shenzhou 6 followed two years later ending the first phase of Project 921. Missions are launched on the Long March 2F rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. The China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) provides engineering and administrative support for the crewed Shenzhou missions.[64]

Space laboratory

The second phase of the Project 921 started with Shenzhou 7, China's first spacewalk mission. Then, two crewed missions were planned to the first Chinese space laboratory. The PRC initially designed the Shenzhou spacecraft with docking technologies imported from Russia, therefore compatible with the International Space Station (ISS). On September 29, 2011, China launched Tiangong 1. This target module is intended to be the first step to testing the technology required for a planned space station.

On October 31, 2011, a Long March 2F rocket lifted the Shenzhou 8 uncrewed spacecraft which docked twice with the Tiangong 1 module. The Shenzhou 9 craft took off on 16 June 2012 with a crew of 3. It successfully docked with the Tiangong-1 laboratory on 18 June 2012, at 06:07 UTC, marking China's first crewed spacecraft docking.[65] Another crewed mission, Shenzhou 10, launched on 11 June 2013. The Tiangong 1 target module is then expected to be deorbited.[66]

A second space lab, Tiangong 2, launched on 15 September 2016, 22:04:09 (UTC+8).[67] The launch mass was 8,600 kg, with a length of 10.4m and a width of 3.35m, much like the Tiangong 1.[68] Shenzhou 11 launched and rendezvoused with Tiangong 2 in October 2016, with an unconfirmed further mission Shenzhou 12 in the future. The Tiangong 2 brings with it the POLAR gamma ray burst detector, a space-Earth quantum key distribution, and laser communications experiment to be used in conjunction with the Mozi 'Quantum Science Satellite', a liquid bridge thermocapillary convection experiment, and a space material experiment. Also included is a stereoscopic microwave altimeter, a space plant growth experiment, and a multi-angle wide-spectral imager and multi-spectral limb imaging spectrometer. Onboard TG-2 there will also be the world's first-ever in-space cold atomic fountain clock.[68]

Space station

A larger basic permanent space station (基本型空间站) would be the third and last phase of Project 921. This will be a modular design with an eventual weight of around 60 tons, to be completed sometime before 2022. The first section, designated Tiangong 3, was scheduled for launch after Tiangong 2,[69] but ultimately not ordered after its goals were merged with Tiangong 2.[70]

This could also be the beginning of China's crewed international cooperation, the existence of which was officially disclosed for the first time after the launch of Shenzhou 7.[71]

The first module of Tiangong space station, Tianhe core module, was launched on 29 April 2021, from Wenchang Space Launch Site.[38] It was first visited by Shenzhou 12 crew on 17 June 2021. The Chinese space station is scheduled to be completed in 2022[72] and fully operational by 2023.

Lunar exploration

In January 2004, the PRC formally started the implementation phase of its uncrewed Moon exploration project. According to Sun Laiyan, administrator of the China National Space Administration, the project will involve three phases: orbiting the Moon; landing; and returning samples. The first phase planned to spend 1.4 billion renminbi (approx. US$170 million) to orbit a satellite around the Moon before 2007, which is ongoing. Phase two involves sending a lander before 2010. Phase three involves collecting lunar soil samples before 2020.

On November 27, 2005, the deputy commander of the crewed spaceflight program announced that the PRC planned to complete a space station and a crewed mission to the Moon by 2020, assuming funding was approved by the government.

On December 14, 2005, it was reported "an effort to launch lunar orbiting satellites will be supplanted in 2007 by a program aimed at accomplishing an uncrewed lunar landing. A program to return uncrewed space vehicles from the Moon will begin in 2012 and last for five years, until the crewed program gets underway" in 2017, with a crewed Moon landing planned after that.[73]

Nonetheless, the decision to develop a totally new Moon rocket in the 1962 Soviet UR-700M-class (Project Aelita) able to launch a 500-ton payload in LTO and a more modest 50 tons LTO payload LV has been discussed in a 2006 conference by academician Zhang Guitian (张贵田), a liquid propellant rocket engine specialist, who developed the CZ-2 and CZ-4A rockets engines.[74][75][76]

On June 22, 2006, Long Lehao, deputy chief architect of the lunar probe project, laid out a schedule for China's lunar exploration. He set 2024 as the date of China's first moonwalk.[77]

In September 2010, it was announced that the country is planning to carry out explorations in deep space by sending a man to the Moon by 2025. China also hoped to bring a Moon rock sample back to Earth in 2017, and subsequently build an observatory on the Moon's surface. Ye Peijian, Commander in Chief of the Chang'e program and an academic at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, added that China has the "full capacity to accomplish Mars exploration by 2013."[78][79]

On December 14, 2013[80] China's Chang'e 3 became the first object to soft-land on the Moon since Luna 24 in 1976.[81]

On 20 May 2018, several months before the Chang'e 4 mission, the Queqiao was launched from Xichang Satellite Launch Center in China, on a Long March 4C rocket.[82] The spacecraft took 24 days to reach L2, using a gravity assist at the Moon to save propellant.[83] On 14 June 2018, Queqiao finished its final adjustment burn and entered the mission orbit, about 65,000 kilometres (40,000 mi) from the Moon. This is the first lunar relay satellite ever placed in this location.[83]

On January 3, 2019, Chang'e 4, the China National Space Administration's lunar rover, made the first-ever soft landing on the Moon's far side. The rover was able to transmit data back to Earth despite the lack of radio frequencies on the far side, via a dedicated satellite sent earlier to orbit the Moon. Landing and data transmission are considered landmark achievements for human space exploration.[84]

As indicated by the official Chinese Lunar Exploration Program insignia, denoted by a calligraphic Moon ideogram (月) in the shape of a nascent lunar crescent, with two human footsteps at its center, the ultimate objective of the program is to establish a permanent human presence on the Earth's natural satellite.

Yang Liwei declared at the 16th Human in Space Symposium of International Academy of Astronautics (IAA) in Beijing, on May 22, 2007, that building a lunar base was a crucial step to realize a flight to Mars and farther planets.[85]

According to practice, since the whole project is only at a very early preparatory research phase, no official crewed Moon program has been announced yet by the authorities. But its existence is nonetheless revealed by regular intentional leaks in the media.[86] A typical example is the Lunar Roving Vehicle (月球车) that was shown on a Chinese TV channel (东方卫视) during the 2008 May Day celebrations.

On 23 November 2020, China launched the new Moon mission Chang'e 5, which returned to Earth carrying lunar samples on 16 December 2020. Only two nations, the United States and the former Soviet Union have ever returned materials from the Moon, thus making China the third country to have ever achieved the feat.[87]

Mission to Mars and beyond

In 2006, the Chief Designer of the Shenzhou spacecraft stated in an interview that:

搞航天工程不是要达成升空之旅, 而是要让人可以正常在太空中工作, 为将来探索火星、土星等作好准备。 Space programs are not aimed at sending humans into space per se, but instead at enabling humans to work normally in space, and prepare for the future exploration of Mars, Saturn, and beyond.

— CAS Academician Qi Faren[88]

Sun Laiyan, administrator of the China National Space Administration, said on July 20, 2006, that China would start deep space exploration focusing on Mars over the next five years, during the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2006–2010) Program period.[89] In April 2020, the Planetary Exploration of China program was announced. The program aims to explore planets of the Solar System, starting with Mars, then expanded to include asteroids and comets, Jupiter and more in the future.[90]

The first mission of the program, Tianwen-1 Mars exploration mission, began on July 23, 2020. A spacecraft, which consisted of an orbiter, a lander, a rover, a remote and a deployable camera, was launched by a Long March 5 rocket from Wenchang.[39] The Tianwen-1 was inserted into Mars orbit in February 2021 after a seven-month journey, followed by a successful soft landing of the lander and Zhurong rover on May 14, 2021.[40]

Space-based solar power

According to the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) presentation at the 2015 International Space Development Congress in Toronto, Canada, Chinese interest in space-based solar power began in the period 1990–1995. By 2011, there was a proposal for a national program, with advocates such as Pioneer Professor Wang Xiji stating in an article for the Ministry of Science and technology that "China had built up a solid industrial foundation, acquired sufficient technology and had enough money to carry out the most ambitious space project in history. Once completed, the solar station, with a capacity of 100MW, would span at least one square kilometre, dwarfing the International Space Station and becoming the biggest man-made object in space" and "warned that if it did not act quickly, China would let other countries, in particular the US and Japan, take the lead and occupy strategically important locations in space."[91] Global Security cites a 2011-01 Journal of Rocket propulsion that articulates the need for 620+ launches of their Long March 9 (CZ-9) heavy-lift system for the construction of an orbital solar power plant with 10,000 MW capacity massing 50,000 tonnes.[92]

By 2013, there was a national goal, that "the state has decided that power coming from outside of the earth, such as solar power and development of other space energy resources, is to be China's future direction" and the following roadmap was identified: "In 2010, CAST will finish the concept design; in 2020, we will finish the industrial level testing of in-orbit construction and wireless transmissions. In 2025, we will complete the first 100kW SPS demonstration at LEO; and in 2035, the 100MW SPS will have an electric generating capacity. Finally in 2050, the first commercial level SPS system will be in operation at GEO."[93] The article went on to state that "Since SPS development will be a huge project, it will be considered the equivalent of an Apollo program for energy. In the last century, America's leading position in science and technology worldwide was inextricably linked with technological advances associated with the implementation of the Apollo program. Likewise, as China's current achievements in aerospace technology are built upon with its successive generations of satellite projects in space, China will use its capabilities in space science to assure sustainable development of energy from space."[93]

In 2015, the CAST team won the International SunSat Design Competition with their video of a Multi-Rotary Joint concept.[94] The design was presented in detail in a paper for the Online Journal of Space Communication.[95][96]

In 2016, Lt Gen. Zhang Yulin, deputy chief of the PLA armament development department of the Central Military Commission, suggested that China would next begin to exploit Earth-Moon space for industrial development. The goal would be the construction of space-based solar power satellites that would beam energy back to Earth.[97]

In June 2021, Chinese officials confirmed the continuation of plans for a geostationary solar power station by 2050. The updated schedule anticipates a small-scale electricity generation test in 2022, followed by a megawatt-level orbital power station by 2030. The gigawatt-level geostationary station will require over 10,000 tonnes of infrastructure, delivered using over 100 Long March 9 launches.[98]

Goals

The China National Space Administration stated that their long-term goals are:

List of launchers and projects

Launch vehicles

- Air-Launched SLV able to place a 50 kilogram plus payload to 500 km SSO[101]

- Kaituozhe-1 (开拓者一号) Solid fueled orbital launch vehicle based on the DF-21 missile with an extra upper stage, which is 4 stages in total.[102]

- Kaituozhe-1A (开拓者一号甲)

- Kaituozhe-1B (开拓者一号乙) with addition of two solid boosters[103]

- Kaituozhe-2 (开拓者二号) A solid fueled orbital launch vehicle with a stage 1 based on the DF-31 missile, accompanied by the small stages 2 and 3.[104]

- Kaituozhe-2A (开拓者一二甲) with addition of two DF-21 based boosters.

- CZ-1D based on a CZ-1 but with a new N2O4/UDMH second stage

- CZ-2E(A) Intended for launch of Chinese space station modules. Payload capacity up to 14 tons in LEO and 9000 (kN) liftoff thrust developed by 12 rocket engines, with enlarged fairing of 5.20 m in diameter and length of 12.39 m to accommodate large spacecraft[105]

- CZ-2F/G Modified CZ-2F without escape tower, specially used for launching robotic missions such as Shenzhou cargo and space laboratory module with payload capacity up to 11.2 tons in LEO[106]

- CZ-3B(A) More powerful Long March rockets using larger-size liquid propellant strap-on motors, with payload capacity up to 13 tons in LEO

- CZ-3C Launch vehicle combining CZ-3B core with two boosters from CZ-2E

- CZ-5 Second generation ELV with more efficient and nontoxic propellants (25 tonnes in LEO)

- CZ-6 or Small Launch Vehicle, with short launch preparation period, low cost and high reliability, to meet the launch need of small satellites up to 500 kg to 700 km SSO, first flight for 2010; with Fan Ruixiang (范瑞祥) as Chief designer of the project[107][108][109]

- CZ-7 used for Phase 4 of Lunar Exploration Program (嫦娥-4 工程), that is permanent base (月面驻留) expected for 2024; Second generation Heavy ELV for lunar and deep space trajectory injection (70 tonnes in LEO), capable of supporting a Soviet L1/L3-like lunar landing mission[110]

- CZ-9 super heavy-lift launch vehicle.

- CZ-11 small, quick-response launch vehicle.

- Project 869 reusable shuttle system with Tianjiao-1 or Chang Cheng-1 (Great Wall-1) orbiters. Project of 1980s-1990s.

- Project 921-3 Reusable launch vehicle current project of the reusable shuttle system.

- Tengyun another current project of two wing-staged reusable shuttle system.

Satellites and science mission

- Space-Based ASAT System small and nano-satellites developed by the Small Satellite Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Space Technology.[111]

- The Double Star Mission comprised two satellites launched in 2003 and 2004, jointly with ESA, to study the Earth's magnetosphere.[112]

- Earth observation, remote sensing or reconnaissance satellites series: CBERS, Dongfanghong program, Fanhui Shi Weixing, Yaogan and Ziyuan 3.

- Tianlian I telecommunication satellite

- Tianlian II (天链二号) Next generation data relay satellite (DRS) system, based on the DFH-4 satellite bus, with two satellites providing up to 85% coverage.[113]

- Beidou navigation system or Compass Navigation Satellite System, composed of 60 to 70 satellites, during the "Eleventh Five-Year Plan" period (2006–2010).[114]

- Astrophysics research, with the launch of the world's largest Solar Space Telescope in 2008, and Project 973 Space Hard X-Ray Modulation Telescope (硬X射线调制望远镜) by 2010.[115]

- Deep Space Tracking Network with the completion of the FAST, the world's largest single dish radio antenna of 500 m in Guizhou, and a 3000 km VLBI radio antenna.[116]

- A Deep Impact-style mission to test process of re-directing the direction of an asteroid or comet.[117]

Crewed LEO Program

- Project 921-1 – Shenzhou spacecraft.

- Tiangong - first three crewed Chinese Space Laboratories.

- Project 921-2 – permanent crewed modular Chinese Space Station[118][119]

- Tianzhou – robotic cargo vessel to resupply the Chinese Space Station, based on the design of Tiangong-1, not meant for reentry, but usable for garbage disposal.[120][121]

- Next-generation crewed spacecraft (货运飞船) – upgrade version of the Shenzhou spacecraft to resupply the Chinese Space Station and return cargo back to Earth.

- Project 921-11 – X-11 reusable spacecraft for Project 921-2 Space Station.

- Tianjiao-1 or Chang Cheng-1 (Great Wall-1) - winged spaceplane orbiters of Project 869 reusable shuttle system. Project of 1980s-1990s.

- Shenlong - winged spaceplane orbiter of current Project 921-3 reusable shuttle system.

- Tengyun - winged spaceplane orbiter in another current project of two wing-staged reusable shuttle system.

- HTS Maglev Launch Assist Space Shuttle - winged spaceplane orbiter in another current shuttle project.

Chinese Lunar Exploration Program

- First phase, Chang'e 1 and Chang'e 2 – launched in 2007 and 2010

- Second phase, Chang'e 3 and Chang'e 4 – launched in 2013 and 2018

- Third phase, Chang'e 5-T1 (completed in 2014) and Chang'e 5 – launched in Dec 2020

- Fourth phase, Chang'e 6, Chang'e 7 and Chang'e 8 – will explore the south pole for natural resources; may 3D-print a structure using regolith.

- Crewed mission: In the 2030s, – crewed lunar missions

Deep Space Exploration Program

China's first deep space probe, the Yinghuo-1 orbiter, was launched in November 2011 along with the joint Fobos-Grunt mission with Russia, but the rocket failed to leave Earth orbit and both probes underwent destructive re-entry on 15 January 2012.[122] In 2018, Chinese researchers proposed a deep space exploration roadmap to explore Mars, an asteroid, Jupiter, and further targets, within the 2020–2030 timeframe.[123][124] Current and upcoming robotic missions include:

- Chinese Deep Space Network relay satellites, for deep-space communication and exploration support network.

- Tianwen-1, launched on 23 July 2020 with arrival at Mars on 10 February 2021. Mission includes an orbiter, a deployable and remote camera, a lander, and the Zhurong rover.[123]

- Tianwen-2, formerly ZhengHe, targeted for launch in 2025. Mission goals include asteroid flyby observations, global remote sensing, robotic landing, and sample return.[123] Tianwen-2 is now in active development.[125]

- Interstellar Express, targeting for launch around 2024–2025 for Interstellar Heliosphere Probe-1 (IHP-1) and around 2025–2026 for Interstellar Heliosphere Probe-2 (IHP-2). Mission objectives include exploration of the heliosphere and interstellar space.[126] Also to become the first non-NASA probes to leave the Solar System.[127]

- Mars Sample Return Mission, initially proposed for launch around 2028–2030.[124][128] Mission goals include in-situ topography and soil composition analysis, deep interior investigations to probe the planet's origins and geologic evolution, and sample return.[123] As of December 2019, the plan is for two launches to be conducted during the November 2028 Earth-to-Mars launch window: a sample collection lander with Mars ascent vehicle on a Long March 3B, and an Earth Return Orbiter on a Long March 5, with samples returning to Earth in September 2031.[129] Earlier plans implemented the mission in a single launch using the Long March 9.[130]

- Jupiter System orbiter, tentatively named Gan De,[131] proposed for launch around 2029–2030,[124][132] and arriving at Jupiter around 2035–2036.[131][128] Mission goals include orbital exploration of Jupiter and its four largest moons, study of the magnetohydrodynamics in the Jupiter system, and investigation of the internal composition of Jupiter's atmosphere and moons,[123] especially Ganymede.[128]

- A mission to Uranus, still tentative, has been proposed for implementation after 2030, with a probe arriving in the 2040s. It is currently envisioned as part of a future planetary flyby phase of exploration, and would study the solar wind and interplanetary magnetic field as well.[123][128][133]

These missions, with the exception of the Uranus mission, have been officially approved or are in the study phase as of June 2017.[133]

Research

The Center for Space Science and Applied Research (CSSAR), was founded in 1987 by merging the former Institute of Space Physics (i.e. the Institute of Applied Geophysics founded in 1958) and the Center for Space Science and Technology (founded in 1978). The research fields of CSSAR mainly cover 1. Space Engineering Technology; 2. Space Weather Exploration, Research, and Forecasting; 3. Microwave Remote Sensing and Information Technology.

See also

- Beihang University

- China and weapons of mass destruction

- Two Bombs, One Satellite

- Chinese women in space

- Harbin Institute of Technology

- French space program

- List of human spaceflights to the Tiangong space station

References

- "How is China Advancing its Space Launch Capabilities?". Center for Strategic and International Studies: China Power.

- Jones, Andrew (February 16, 2022). "China aims to complete space station, break launch record in 2022". Space.com.

- Myers, Steven Lee (October 15, 2021). "The Moon, Mars and Beyond: China's Ambitious Plans in Space". The New York Times.

- DF-1. GlobalSecurity.org.

- "This Day in History: October 4". History.com. November 24, 2009.

- Howell, Elizabeth (September 29, 2020). "Explorer 1: The First U.S. Satellite". Space.com.

- "KSP History Part 104 - FSW-0 No. 1". Imgur. November 2, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- "FSW-0 (Jianbing 1)". SinoDefence.com. September 16, 2011. Archived from the original on November 8, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- Jacobs, Andrew (June 3, 2010). "In Leaked Lecture, Details of China's News Cleanups". The New York Times.

- Pomfret, John (October 16, 2003). "China's First Space Traveler Returns a Hero". The Washington Post.

- Song, Wanyuan; Tauschinski, Jana (July 26, 2022). "China space station: What is the Tiangong?". BBC.

- "China plans to complete space station with latest mission". ABC News. Associated Press. June 4, 2022.

- China's Space Program: A 2021 Perspective (Report). January 28, 2022.

- Kwon, Karen (June 25, 2020). "China Reaches New Milestone in Space-Based Quantum Communications". Scientific American.

- "赵九章与中国卫星" [Zhao Jiuzhang and China Satellite] (in Chinese). 中国科学院. October 16, 2007. Archived from the original on March 14, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- Futron Corp. (2003). "China and the Second Space Age" (PDF). Futron Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- "回收生物返回舱". 雷霆万钧. September 19, 2005. Archived from the original on December 22, 2005. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- "首批航天员19人胜出 为后来积累了宝贵的经验". 雷霆万钧. September 16, 2005. Archived from the original on December 22, 2005. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- "第一艘无人试验飞船发射成功—回首航天路". cctv.com. October 5, 2005. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- "《东方红卫星传奇》". 中国中央电视台. July 3, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- Clark, Stephen. "Chinese TV broadcasting satellite launched on 300th Long March rocket". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "中国载人航天史上的四组神秘代号 都是什么含义?". Xinhua Net (in Chinese). June 17, 2021. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- "江泽民总书记为长征-2F火箭的题词". 平湖档案网. January 11, 2007. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- "中国机械工业集团公司董事长任洪斌一行来中国运载火箭技术研究院考察参观". 中国运载火箭技术研究院. July 28, 2008. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- "江泽民为"神舟"号飞船题名". 东方新闻. November 13, 2003. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- "中国战略秘器"神龙号"空天飞机惊艳亮相". 大旗网. June 6, 2008. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- "基本概况". 中国科学院上海光学精密机械研究所. September 7, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- "金怡濂让中国扬威 朱镕基赞他是"做大事的人"". 搜狐. February 23, 2003. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- "Management_CHINA MANNED SPACE". Official Website of China Manned Space. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- "History". China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- "All components of the docking mechanism was designed and manufactured in-house China". Xinhua News Agency. November 3, 2011. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- "China next year manual spacecraft Temple docking, multiply group has completed primary". Beijing News. November 4, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- "工程简介". 中国探月与深空探测网. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- "Programming glitch, not radiation or satellites, doomed Phobos-Grunt". 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- "Orbital Launches of 2018". Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- Jones, Andrew (June 23, 2021). "China launches final satellite to complete Beidou system, booster falls downrange". SpaceNews. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- "Xi officially announces commissioning of BDS-3 navigation system". August 1, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- Jones, Andrew (April 29, 2021). "China launches Tianhe space station core module into orbit". SpaceNews. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- Jones, Andrew (July 23, 2020). "Tianwen-1 launches for Mars, marking dawn of Chinese interplanetary exploration". SpaceNews. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- Jones, Andrew (May 14, 2021). "China's Zhurong Mars rover lands safely in Utopia Planitia". SpaceNews. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- China launches rocket from space platform into near space

- "Status of International Agreements relating to activities in outer space as at 1 January 2014" (PDF). United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- "中方反对美以出售禁运武器为由制裁中国公司". 新浪. January 9, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- Ian Sample (October 5, 2013). "US scientists boycott Nasa conference over China ban". The Guardian. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Seitz, Virginia (September 11, 2011), "Memorandum Opinion for the General Counsel, Office of Science and Technology Policy" (PDF), Office of Legal Counsel, 35, archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2012, retrieved May 23, 2012

- Oberhaus, Daniel (October 18, 2016). "Will NASA Ever Work With China?". Popular Mechanic. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- Kavalski, Emilian (2016). The Ashgate Research Companion to Chinese Foreign Policy. Oxon: Routledge. p. 404. ISBN 9781409422709.

- Sample, Ian (October 5, 2013). "US scientists boycott Nasa conference over China ban". The Guardian. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- "航天科技游圣地—东风航天城". 新华网内蒙古频道. December 5, 2007. Archived from the original on July 24, 2009. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- "烟台航天城"起航"了 力争成我国航天技术发展基地". 水母网. April 2, 2005. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- "烟台大众网一神舟六号专题:513所简介". 烟台大众网. June 6, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- "航天○六一基地自主创新促发展". 国家航天局网. July 14, 2008. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- "中国第一枚自行设计制造的试验 探空火箭T-7M发射场遗址". 南汇医保信息网. June 19, 2006. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- "军事史话(第七部) 导弹部队史话". 蓝田玉PDF小说网. March 1, 2008. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- "贝时璋院士:开展宇宙生物学研究". 新浪. November 15, 2006. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- "远望六号航天测量船交付将执行神七任务". 人 民 网. April 14, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- "我国首颗中继卫星发射成功 将测控神七飞行". 人 民 网. April 26, 2008. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- "天链一号01星发射现场DV实录". 新浪. April 27, 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- "精密测轨嫦娥二号 "即拍即显"". 上海科技. June 18, 2008. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- "海南省三亚市新型综合航天测控站建成并投入使用". 中国政府网. April 25, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- "South Tarawa Island, Republic of Kiribati". Global Security. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- Londoño, Ernesto (July 28, 2019). "From a Space Station in Argentina, China Expands Its Reach in Latin America". The New York Times.

- "Chinese Crewed Capsule 1978". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2009. "Encyclopedia Astronautica Index: 1". Archived from the original on August 28, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- "China's Crewed Space Program Takes the Stage at 26th National Space Symposium". The Space Foundation. April 10, 2010. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- Jonathan Amos (June 18, 2012). "Shenzhou-9 docks with Tiangong-1". BBC. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- "Chinese Shenzhou craft launches on key space mission". BBC News. October 31, 2011. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- Katie Hunt and Deborah Bloom (September 15, 2016). "China launches Tiangong-2 space lab". CNN. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- Rui Barbosa (September 14, 2016). "China launches Tiangong-2 orbital module". NASASPACEFLIGHT.com. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

-

David, Leonard (March 11, 2011). "China Details Ambitious Space Station Goals". SPACE.com. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

China is ready to carry out a multiphase construction program that leads to the large space station around 2020. As a prelude to building that facility, China is set to loft the Tiangong-1 module this year as a platform to help master key rendezvous and docking technologies.

- "脚踏实地,仰望星空—访中国载人航天工程总设计师周建平". Chinese Government. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- "权威发布:神舟飞船将从神八开始批量生产". 新华网. September 26, 2008. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- "China takes first step towards space station". Financial Times. September 20, 2011.

- "NewsFactor". NewsFactor.

- "针对我们国家登月火箭的猜测". 虚幻军事天空. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- "中国载人登月火箭及其动力系统设想". 国家航天局网. July 25, 2006. Archived from the original on March 14, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- "河北院士联谊". 河北院士联谊会秘书处. Archived from the original on September 14, 2007. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- "news.com.com". news.com.com. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- "China a Step Ahead in Space Race". The Wall Street Journal. September 28, 2010.

- "China to send man to moon by 2025". French Tribune. September 21, 2010. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- "China lands Jade Rabbit robot rover on Moon". BBC. December 14, 2013.

- Simon Denyer (December 14, 2013). "China carries out first soft landing on moon in 37 years". Washington Post.

- Barbosa, Rui; Bergin, Chris (May 20, 2018). "Queqiao relay satellite launched ahead of Chang'e-4 lunar mission". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- Xu, Luyuan (June 15, 2018). "How China's lunar relay satellite arrived in its final orbit". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018.

- Rivers, Matt; Regan, Helen; Jiang, Steven (January 3, 2019). "China lunar rover successfully touches down on far side of the moon, state media announces". CNN. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- "Astronauts share their experiences". People Daily. May 22, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- "China has no timetable for crewed moon landing". Xinhua News Agency. November 26, 2007. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- "China launches ambitious mission to bring back samples from the Moon". The Verge. November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- "戚发韧:神六后中国航天面临极大挑战". 人 民 网. January 15, 2006. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- People's Daily Online - Roundup: China to develop deep space exploration in five years

- Jones, Andrew (April 24, 2020). "China's Mars mission named Tianwen-1, appears on track for July launch". SpaceNews. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- Thevision (September 4, 2011). "Billion Year Plan: China Space Agency Looks To Capture Sun's Power". Billion Year Plan. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- Pike, John. "CZ-9 Chinese Manned Lunar Booster". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- Communication, Online Journal of Space. "Online Journal of Space Communication". spacejournal.ohio.edu. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Multi-Rotary Joints SPS - 2015 SunSat Design Competition" – via www.youtube.com.

- "Online Journal of Space Communication".

- Communication, Online Journal of Space. "Online Journal of Space Communication". spacejournal.ohio.edu. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- "Exploiting earth-moon space: China's ambition after space station". news.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- Jones, Andrew (June 28, 2021). "China's super heavy rocket to construct space-based solar power station". SpaceNews. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- "Senior officer expects moon visit by 2036 - China - Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn.

- "When will China get to Mars?". BBC News.

- "空射运载火箭亮相珠海航展". 新华网. November 1, 2006. Archived from the original on February 7, 2008. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- "Kaituozhe-1 (KT-1)". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- "开拓者一号乙固体运载火箭". 虚幻军事天空. July 17, 2008. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- "KT-2 (Kaituozhe)". www.b14643.de. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- "CZ-2EA地面风载试验". 中国空气动力研究与发展中心. February 4, 2008. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- "独家:"神八"将用改进型火箭发射 2010年左右首飞". 人民网. June 25, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- "让年轻人与航天事业共同成长". 中国人事报. March 14, 2008. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- 中国科学技术协会 (2007). 航天科学技术学科发展报告. Beijing, PRC: 中国科学技术协会出版社. p. 17. ISBN 978-7504648662. Archived from the original on September 11, 2008.

- "国际空间大学公众论坛关注中国航天(3)". People Daily. July 11, 2007. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- "Chinese Crewed Space Program: The Future". Go Taikonauts!. February 4, 2006. Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- "中国深空前沿:军事潜力巨大的小卫星研究(组图)". 腾讯新闻. July 19, 2004. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- "The first Sino-European satellite completes its mission". ESA. October 16, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- "我国现役和研制中的卫星与飞船谱系图:上排右一会不会是TL-2". 虚幻天空. June 8, 2008. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- "China constructs space information "highway"". People Daily. May 23, 2007. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- "硬X射线调制望远镜HXMT". 硬X射线天文望远镜项目组. April 16, 2004. Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- "500米口径球面射电望远镜(FAST)". 中科院大科学装置办公室. April 21, 2008. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- "After US, China plans 'Deep Impact' mission - The Economic Times". Reuters. Archived from the original on August 30, 2005. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- "中国空间实验室". 虚幻军事天空. February 13, 2006. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- "中国航天921-III计划". 虚幻军事天空. July 15, 2008. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- "China expects to launch cargo ship into space around 2016". Space Daily. March 6, 2014.

- Morris Jones (March 3, 2014). "The Next Tiangong". Space Daily.

- "Russia, China could sign Moon exploration pact in 2006". RIA Novosti. September 11, 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- Xu, Lin; Zou, Yongliao; Jia, Yingzhuo (2018). "China's planning for deep space exploration and lunar exploration before 2030" (PDF). Chinese Journal of Space Science. 38 (5): 591–592. doi:10.11728/cjss2018.05.591.

- Wang, F. (June 27, 2018), "China's Cooperation Plan on Lunar and Deep Space Exploration" (PDF), Sixty-first session (2018) of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, UNOOSA, retrieved January 23, 2019.

- Andrew Jones published (May 18, 2022). "China to launch Tianwen 2 asteroid-sampling mission in 2025". Space.com. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- Jones, Andrew (April 16, 2021). "China to launch a pair of spacecraft towards the edge of the solar system". SpaceNews. SpaceNews. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- Song, Jianlan. ""Interstellar Express": A Possible Successor of Voyagers". InFocus. Chinese Academy of Sciences. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- Jones, Andrew (July 14, 2017). "Mars, asteroids, Ganymede and Uranus: China's deep space exploration plan to 2030 and beyond". GBTimes. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- @EL2squirrel (December 12, 2019). "China's second Mars exploration mission is a Mars Sample Return mission: Earth Return Orbiter will be launched in 2028, another launch for Lander&Ascender, Earth Entry Vehicle will be return in 2031. pbs.twimg.com/media/ELo1S31UYAAcbMf?format=jpg&name=large" (Tweet). Retrieved December 13, 2019 – via Twitter.

- Jones, Andrew (December 19, 2019). "A closer look at China's audacious Mars sample return plans". The Planetary Society. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- Jones, Andrew (January 12, 2021). "Jupiter Mission by China Could Include Callisto Landing". The Planetary Society. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- "China outlines roadmap for deep space exploration". SpaceDaily. April 26, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- Jones, Andrew (July 10, 2017). "In Beijing, China rolls out the red carpet — and a comprehensive space plan". SpaceNews. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

-

Geoff Brumfiel (September 7, 2020). "New Chinese Space Plane Landed At Mysterious Air Base, Evidence Suggests". National Public Radio. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

The photo, which is too low resolution to be conclusive, was snapped by the San Francisco-based company Planet. It shows what could be the classified Chinese spacecraft on a long runway, along with several support vehicles lined up nearby.

-

Stephen Clark (September 8, 2020). "China tests experimental reusable spacecraft shrouded in mystery". spaceflightnow.com. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

The spacecraft took off on top of a Long March 2F rocket Friday from the Jiuquan launch base in the Gobi Desert of northwestern China, according to a statement from the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corp., or CASC, the state-owned company that oversees China’s space industry.

-

"China's reusable experimental spacecraft back to landing site". Xinhuanet. Jiuquan. September 6, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

The successful flight marked the country's important breakthrough in reusable spacecraft research and is expected to offer convenient and low-cost round trip transport for the peaceful use of the space.

-

"China launches reusable experimental spacecraft". Xinhuanet. Jiuquan. September 4, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

After a period of in-orbit operation, the spacecraft will return to the scheduled landing site in China. It will test reusable technologies during its flight, providing technological support for the peaceful use of space.

-

Ryan Woo; Stella Qiu; Simon Cameron-Moore (September 6, 2020). "Reusable Chinese Spacecraft Lands Successfully: State Media". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

Chinese social media has been rife with speculation over the spacecraft, which some commentators compared to the U.S. Air Force's X-37B, an autonomous spaceplane made by Boeing that can remain in orbit for long periods of time before flying back to Earth on its own.

External links

- China National Space Administration

- Center for Space Science and Applied Research – Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS)

- 《宇航学报》 的免费电子版 – Journal of Astronautics published by the Chinese Society of Astronautics

- Go Taikonauts! – An Unofficial Chinese Space Website

- Mark Wade's Encyclopedia Astronautica

- China's Space Ambitions, analysis by Joan Johnson-Freese, IFRI Proliferation Papers n° 18, 2007

- US Senate testimony on Chinese space program, given by James Oberg.

- Excerpts from Senate Q&A period on Chinese space program

- Dragon Space – China's civilian, military and crewed space programs

- Chinese Threat to American Leadership in Space – Analysis by Gabriele Garibaldi

- Chinese Astronaut Biographies

- Scientific American Magazine (October 2003 Issue) China's Great Leap Upward

- White paper on china space activities the coming 5 years (released 2006)

- Video of China's first spacewalk

- Chinese Space Program: a Photographic History

.jpg.webp)