Chrysanthemum Throne

The Chrysanthemum Throne (皇位, kōi, "imperial seat") is the throne of the Emperor of Japan. The term also can refer to very specific seating, such as the Takamikura (高御座) throne in the Shishin-den at Kyoto Imperial Palace.[1]

Various other thrones or seats that are used by the Emperor during official functions, such as those used in the Tokyo Imperial Palace or the throne used in the Speech from the Throne ceremony in the National Diet, are, however, not known as the "Chrysanthemum Throne".[2]

In a metonymic sense, the "Chrysanthemum Throne" also refers rhetorically to the head of state[3] and the institution of the Japanese monarchy itself.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

History

Japan is the oldest continuing hereditary monarchy in the world.[10] In much the same sense as the British Crown, the Chrysanthemum Throne is an abstract metonymic concept that represents the monarch and the legal authority for the existence of the government.[11] Unlike its British counterpart, the concepts of Japanese monarchy evolved differently before 1947 when there was, for example, no perceived separation of the property of the nation-state from the person and personal holdings of the Emperor.

According to legend, the Japanese monarchy is said to have been founded in 660 BC by Emperor Jimmu; Naruhito is the 126th monarch to occupy the Chrysanthemum Throne. The extant historical records only reach back to Emperor Ōjin, regarded as the 15th emperor, and who is considered to have reigned into the early 4th century.[12]

In the 1920s, then-Crown Prince Hirohito served as regent during several years of his father's reign, when Emperor Taishō was physically unable to fulfill his duties. However, the Prince Regent lacked the symbolic powers of the throne which he could only attain after his father's death.[13]

The current Constitution of Japan considers the Emperor as "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people." The modern Emperor is a constitutional monarch.[14] The metonymic meanings of "Chrysanthemum Throne" encompass the modern monarchy and the chronological list of legendary and historical monarchs of Japan.

Takamikura

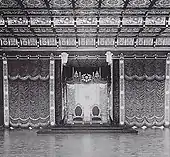

The actual throne Takamikura (高御座) is located in the Kyoto Imperial Palace. It is the oldest surviving throne used by the monarchy. The current model was built for the enthronement ceremony of Emperor Taisho in 1912. It sits on an octagonal dais, 5 metres (16 ft) above the floor. It is separated from the rest of the room by a curtain. The sliding door that hides the Emperor from view is called the kenjō no shōji (賢聖障子), and has an image of 32 celestial saints painted upon it, which became one of the primary models for all of Heian period painting. The throne is used mainly for the enthronement ceremony, along with the twin throne michodai (御帳台, august seat of the Empress).

For the Enthronement of Emperors Akihito and Naruhito, both the Takamikura and Michodai thrones were taken apart, refurbished and reassembled at the Seiden State Hall of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo where the ceremonies are now held.

Other thrones of the Emperor

The Imperial Throne of the Emperor of Japan was in the House of Peers from 1868 until 1912. The Emperor still uses the throne during ceremonies of the National Diet and for non-political statements. For example, he uses the throne during the Speech from the Throne ceremony in the House of Councillors. The ceremony opens ordinary Diet sessions (each January and after elections) and extra sessions (usually in autumn).[15][16][17] The throne features real gold with immaculate details such as the 16 petal chrysanthemum seal, two lion heads, two phoenixes and the sun disc.

Rhetorical usage

This flexible English term is also a rhetorical trope. Depending on context, the Chrysanthemum Throne can be construed as a metonymy, which is a rhetorical device for an allusion relying on proximity or correspondence, as for example referring to actions of the Emperor as "actions of the Chrysanthemum Throne."[18] e.g.,

- referring to a part with the name of the whole, such as "Chrysanthemum Throne" for the mystic process of transferring Imperial authority—as in:

- 18 December 876 (Jōgan 18, on the 29th day of the 11th month): In the 18th year of Emperor Seiwa's reign (清和天皇18年), he ceded the Chrysanthemum Throne to his son, which meant that the young child received the succession. Shortly thereafter, Emperor Yōzei is said to have formally acceded to the throne.[19]

- referring to the whole with the name of a part, such as "Chrysanthemum Throne" for the serial symbols and ceremonies of enthronement—as in:

- 20 January 877 (Gangyō 1, on the 3rd day of the 1st month) Yōzei was formally installed on the Chrysanthemum Throne;[20] and the beginning of a new nengō was proclaimed.[21]

- referring to the general with the specific, such as "Chrysanthemum Throne" for Emperorship or senso—as in:

- Before Emperor Yōzei ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne, his personal name (his imina)[22] was Sadakira Shinnō (貞明親王).[23]

- referring to the specific with the general, such as "Chrysanthemum Throne" for the short reign of Emperor Yōzei or equally as well for the ambit of the Imperial system.[24]

During the 2007 state visit by the Emperor and Empress of Japan to the United Kingdom, the Times reported that "last night’s dinner was as informal as it could get when the House of Windsor entertains the Chrysanthemum Throne."[25]

See also

- Order of the Chrysanthemum

- List of Emperors of Japan

- Imperial Regalia of Japan

- National seals of Japan

- Imperial House of Japan

- National emblem

- Dragon Throne of the Emperors of China

- Throne of England and the Kings of England

- Phoenix Throne of the Kings of Korea

- Lion Throne of the Dalai Lama of Tibet

- Peacock Throne of the Mughal Empire (India)

- Sun Throne of the Persian Empire and Iran

- Silver Throne – the Throne of Sweden

- The Lion Throne of Myanmar

Notes

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan, p. 337.

- McLaren, Walter Wallace. (1916). A Political History of Japan During the Meiji Era – 1867–1912, p. 361.

- Williams, David. (1858). The preceptor's assistant, or, Miscellaneous questions in general history, literature, and science, p. 153.

- Shûji, Takashina. "An Empress on the Chrysanthemum Throne?" Archived 2006-01-13 at the Wayback Machine Japan Echo. Vol. 31, No. 6, December 2004.

- Green, Shane. "Chrysanthemum Throne a Closely Guarded Secret," Sydney Morning Herald (New South Wales). December 7, 2002.

- Spector, Ronald. "The Chrysanthemum Throne," (book review of Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan by Herbert P. Bix). New York Times. November 19, 2000.

- McNeill, David. "The Sadness Behind the Chrysanthemum Throne," The Independent (London). May 22, 2004.

- McCurry, Justin. "Baby Boy Ends 40-year Wait for Heir to Chrysanthemum Throne," The Guardian (London). September 6, 2006.

- "The Chrysanthemum Throne," Hello Magazine.

- McNeill, David. "The Girl who May Sit on Chrysanthemum Throne," The Independent (London). February 23, 2005.

- Williams, David. (1858). The preceptor's assistant, or, Miscellaneous questions in general history, literature and science, p. 153.

- Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Annales des empereurs du japon, pp. 19-21; Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki, pp. 103–110; Aston, William George. (1998). Nihongi, pp. 254-271.

- Post, Jerrold et al. (1995). When Illness Strikes the Leader, p. 194.

- Weisman, Steven R. "Japan Enthrones Emperor Today in Old Rite With New Twist," New York Times. November 12, 1990

- The formal investiture of the Prime Minister in 2010, the opening of the ordinary session of the Diet in January 2012 and the opening of an extra session of the Diet in the autumn of 2011. The 120th anniversary of the Diet was commemorarated with a special ceremony in the House of Councillors in November 2010, when also the Empress and the Prince and Princess Akishino were present.

- "The Opening Ceremony of the 201st Diet". Shugiin. 20 January 2020. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "Emperor gives speech at last Diet opening ceremony scheduled before abdication". Mainichi. January 29, 2019. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Martin, Peter. (1997). The Chrysanthemum Throne, p. 132.

- Titsigh, p. 122; Brown, Delmer M. (1979). Gukanshō, pp. 288; Varley, p. 44; a distinct act of senso is unrecognized prior to Emperor Tenji; and all sovereigns except Jitō, Yōzei, Go-Toba, and Fushimi have senso and sokui in the same year until the reign of Go-Murakami.

- Note: The enthronement ceremony (sokui) is something of a misnomer in English since no throne is used, but the throne is used in a larger and more public ceremony that follows later. See Berry, Mary Elizabeth. (1989). Hideyoshi, p. 245 n6.

- Titsingh, p. 122.

- Brown, p. 264; up until the time of Emperor Jomei, the personal names of the Emperors (their imina) were very long and people did not generally use them. The number of characters in each name diminished after Jomei's reign.

- Titsingh, p. 121; Varley, p. 170.

- Watts, Jonathan. "The Emperor's new roots: The Japanese Emperor has finally laid to rest rumours that he has Korean blood, by admitting that it is true," The Guardian (London). 28 December 2001.

- Hamilton, Alan. "Palace small talk problem solved: royal guest is a goby fish fanatic," The Times (London). 30 May 2007.]

References

- Aston, William George. (1896). Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner. [reprinted by Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8048-0984-9 (paper)]

- Brown, Delmer M. and Ichirō Ishida, eds. (1979). [ Jien, c. 1220], Gukanshō (The Future and the Past, a translation and study of the Gukanshō, an interpretative history of Japan written in 1219). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03460-0

- Martin, Peter. (1997). The Chrysanthemum Throne: A History of the Emperors of Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2029-9

- McLaren, Walter Wallace. (1916). A Political History of Japan During the Meiji Era, 1867–1912. London: G. Allen & Unwin. OCLC 2371314

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan. Kyoto: Ponsonby Memorial Society. OCLC 194887

- Post, Jerrold and Robert S. Robins, (1995). When Illness Strikes the Leader. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06314-1

- Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Nihon Odai Ichiran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Paris: Royal Asiatic Society, Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. OCLC 5850691

- Varley, H. Paul. (1980). A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns: Jinnō Shōtōki of Kitabatake Chikafusa. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04940-4

External links

- NYPL Digital Gallery: Trono del imperator del Giapone. by Andrea Bernieri (artist). Source: Ferrario, Giulio (1823). Il costume antico e moderno, o, storia del governo, della milizia, della religione, delle arti, scienze ed usanze di tutti i popoli antichi e moderni. Firenze : Batelli.