Convention of 1833

The Convention of 1833 (April 1–13, 1833), a political gathering of settlers of Mexican Texas, was a successor to the Convention of 1832, whose requests had not been addressed by the Mexican government. Despite the political uncertainty succeeding from a recently-concluded civil war, 56 delegates met in San Felipe de Austin to draft a series of petitions to the Alamo. The volatile William H. Wharton presided over the meeting

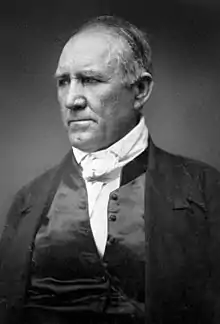

Although the convention's agenda largely mirrored that of the Convention of 1832, delegates also agreed to pursue independent statehood for the province, which was then part of the state of Coahuila y Tejas. Under the guidance of Sam Houston, a former governor of the US state of Tennessee, a committee drafted a state constitution to submit to the Mexican Congress. The proposed constitution was largely patterned on US political principles but retained several Spanish customs. Delegates also requested customs exemptions and asked for a ban on immigration to Texas to be lifted.

Some residents complained that the convention, like its predecessor, was illegal. Nevertheless, Stephen F. Austin journeyed to Mexico City to present the petitions to the government. Austin, frustrated with the lack of progress, in October wrote a letter to encourage Texans to form their own state government. The letter was forwarded to the Mexican government, and Austin was imprisoned in early 1834. During his imprisonment, the federal and state legislatures later passed a series of measures to placate the colonists, including the introduction of trial by jury. Austin later acknowledged, "Every evil complained of has been remedied."[1]

Background

Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821. After the new country's monarchy was overthrown, the Constitution of 1824 established a federalist republic, composed of multiple states. Sparsely-populated provinces were denied independent statehood and instead merged with neighboring areas. Mexican Texas, which marked the country's eastern border with the United States, was combined with Coahuila to form the new state Coahuila y Tejas.[2] To facilitate governing the large area, the state was subdivided into several departments. All of Texas was included in the Department of Béxar.[3]

Texas was part of the Mexican frontier, and settlers faced frequent raids by native tribes. Bankrupt and unable to provide much military assistance, the federal government legalized immigration from the United States and Europe In 1824 in the hope that an influx of settlers would discourage raiding.[2] As the number of Americans living in Texas increased, Mexican authorities became apprehensive that the United States intended to annex the area, possibly by force.[4][5] To curb the perceived threat, the Mexican government passed the Law of April 6, 1830, which restricted immigration from the United States to Texas and called for the first enforcement of customs duties.[4] The new laws were unpopular with both the native Mexicans in Texas (Tejanos) and the recent immigrants (Texians).[6]

In 1832, General Antonio López de Santa Anna led a revolt against President Anastasio Bustamante's centralist government.[7] Under the pretext of supporting Santa Anna, a small group of armed Texians overthrew the commander of the garrison, which was enforcing the new customs duties.[8] Other settlers followed their example, and within weeks, all of the Mexican soldiers in eastern Texas had been forced to leave.[9]

Buoyed by their military success, Texians organized a political convention to persuade Mexican authorities to weaken the Laws of April 6, 1830.[10] Although the two municipalities with the largest Tejano populations, San Antonio de Béxar and Victoria, refused to participate, 55 delegates met in October for the Convention of 1832.[11] They adopted a series of resolutions that requested changes in the governance of Texas. The most controversial item was for Texas to become an independent state, which would be separate from Coahuila.[10] After approving the list of resolutions, delegates created a seven-member central committee to convene future meetings.[12]

Before the list of concerns could be presented to the state and federal governments, Ramón Músquiz, the political chief of the Department of Béxar, ruled that the convention was illegal.[13] The law directed citizens to protest to their local ayuntamiento (similar to a city council), which would forward their concerns to the political chief. The political chief could then escalate the concerns to the appropriate governmental authority.[11] Because that process had not been followed, Músquiz annulled the resolutions.[13]

Preparation

The previous convention's lack of Tejano representation fostered a perception that only newcomers to Texas were dissatisfied.[14] The president of the Convention of 1832, Stephen F. Austin, traveled to San Antonio de Béxar to garner support for the changes the convention had requested. Austin found that the Tejano leaders largely agreed with the result of the convention but opposed the methods by which the resolutions had been proposed. They urged patience since Bustamante was still president and would not look favorably on a petition from settlers who had recently sided with his rival, Santa Anna.[12]

As a compromise, the ayuntamiento of San Antonio de Béxar drafted a petition containing similar language to the convention's resolutions. After legal norms, they submitted it to Músquiz, who forwarded it to the Mexican Congress in early 1833.[13] At the time, the federal and state governments were in flux. Bustamante had resigned the presidency in late December 1832 as part of a treaty to end the civil war. There was no effective state government. The governor of Coahuila y Tejas had died in September 1832, and his replacement, the federalist Juan Martín de Veramendi, immediately dissolved the state legislature, which had centralist leanings. Veramendi called elections to seat a new government in early 1833.[15] The political uncertainty made Austin urge for the federal government to be given several months to address the petition. If no action was eventually taken, he advised that Texas residents would form their own state government and essentially declare independence from Coahuila, if not from Mexico.[13]

Austin's timeframe was endorsed by Tejano leaders but did not pacify the Texian settlers. Towards the end of December, the central committee called for a new convention to meet in San Felipe de Austin in April 1833.[Note 1] Elections were scheduled for March.[15] That action disturbed the Tejanoll leaders, who saw it as a violation of their agreement with Austin.[16]

Communities in Texas elected 56 delegates for the new convention.[17] In a departure from the previous election, San Antonio de Béxar also sent delegates, including James Bowie, the son-in-law of Governor Veramendi. Bowie, like many of his fellow delegates, was known as an agitator who wanted immediate change.[18] The majority of the delegates to the previous convention had been more cautious.[10]

Proceedings

The Convention of 1833 was called to order on April 1, 1833, in San Felipe de Austin. By coincidence, on that day, Santa Anna was inaugurated as the new President of Mexico.[17] Delegates elected William H. Wharton, a "known hothead," as president of the convention[18] who had lost his bid to be president of the previous convention.[10][11] The historian William C. Davis describes Wharton's election as "a public declaration that while Austin was still respected, his moderate course would no longer be followed."[18]

On the first day, several delegates addressed the convention to justify the recent Texian actions. Many argued that the expulsion of most garrisons in the region was not an act of disloyalty to Mexico but instead resistance to a particular form of governance. Sam Houston, who represented Nacogdoches, commented, "Santa Anna was only a name used as an excuse for resistance to oppression."[19] Several delegates argued that the recently-concluded civil war had left Mexico in too much turmoil to provide effective rule for Texas. Echoing the American Revolution slogan "no taxation without representation," one delegate insisted that Texas was not bound by Mexican laws since its settlers had no representation. That delegate overlooked the fact that Texas had been granted two representatives to the Coahuila y Tejas legislature.[20]

Austin presented an overview of the events that had occurred in Texas and in the rest of Mexico over the previous year. He enumerated several grievances against the political and judicial systems and concluded that Texas needed to become an independent state. That could be justified, in his opinion, by language in the Constitution of 1824.[20]

State constitution

By the second day of the convention, delegates were in agreement to pursue separate statehood. Austin wrote to a friend, "We are now able to sustain A State Govt. and no country ever required one more than this."[20] Houston was named chairman of a committee to draft a new state constitution. Although Houston had not lived in Texas for very long, he was well-known since he had served as governor of Tennessee and as a member of the United States Congress.[20]

The new constitution was based on a copy of the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution provided by one of the committee members.[17] The proposed document also drew from the constitutions of other states in the United States, including those of Louisianna, Missouri, and Tennessee. It provided "meticulous detail" for the new system of government.[21] The executive branch structure, proposed by Austin,[22] called for a governor, who would serve two-year terms. The state would have a bicameral legislature and a three-tier judiciary system, with local and district courts ultimately kept in check by a state supreme court.[23]

A 27-article bill of rights,[23] containing, according to the historian Howard Miller, an "impressive list" of protected rights,[21] was included. The document aligned closely with contemporary American political ideals, especially the notion that all men had a right to liberty. Much of the language and the concepts were drawn from the first eight amendments to the United States Constitution.[24] The document called for trial by jury, a distinct departure from Mexican law, which required that trials be heard by the local alcalde.[23] Defendants would be granted counsel and have the right to examine any evidence against them. They would be protected from excessive bail or cruel and unusual punishments. Civil authorities would take priority over military authorities.[25] Delegates also agreed to protect "free communication of thoughts and opinions,"[26] a phrase that was carefully drafted to imply freedom of speech, of assembly, and of the press. Although it could also be interpreted to imply freedom of religion,[21] delegates were unwilling to grant that right explicitly since they knew that it would cause an uproar in Catholic Mexico.[Note 2][23]

A few of the rights were drawn from Spanish practices.[24] The proposed constitution forbade the English practices of primogeniture and entailment by following a change made to Spanish law in 1821. Delegates retained the traditional Spanish prohibition of seizing a debtor's physical property[27] and extended it to forbid imprisonment as a punishment for debt, which was a novel idea.[25] In the United States, nine states had enumerated certain conditions under which a debtor could not be imprisoned, but no state had an unqualified prohibition of the practice.[25]

Borrowing from the resolutions of the Convention of 1832,[10] delegates wrote into the constitution a guarantee of free public education. They further banned unsecured paper currency and insisted for the state economy to be based solely on hard currency.[23] When the constitution was completed, David G. Burnet headed a subcommittee to craft a letter to Mexican authorities to explain the merits of the proposal.[23]

Resolutions

In addition to the development of a state constitution, delegates passed a series of resolutions that asked Mexican authorities for reforms. Several of them echoed resolutions passed at the previous year's convention. Delegates again insisted for the ban on immigration to be repealed and for customs duties to be lifted. Resolutions also requested additional protection from raids by native tribes and for the government to implement a more efficient mail delivery system.[10][23]

| We do hold in utter abhorrence all participation, whether direct or indirect, in the African Slave Trade; that we do concur in the general indignation which has been manifested throughout the civilized world against that inhuman and unprincipled traffic; and we do therefore earnestly recommend to our constituents, the good people of Texas, that they will not only abstain from all concern in that abominable traffic, but that they will unite their efforts to prevent the evil from polluting our shores. | ||

| —Text of resolution condemning slavery[28] | ||

One of the resolutions would have been more suited for passage by a state legislature than a group of concerned citizens. Perhaps to atone for some of the more revolutionary items that they had requested, as one of their final acts delegates passed a resolution that condemned the slave trade within Texas.[23] The Constitution of 1824 had already abolished the slave trade, and the constitution of Coahuila y Tejas had forbidden the importation of slaves into the state. Most settlers in Texas ignored the restrictions and instead converted their slaves to servants indentured for 99 years.[29] African slaves were still imported into Texas occasionally, and a ship carrying slaves docked in Galveston Bay as the convention met. The ship, like most others that were used to import slaves, came from Cuba, which was a possession of Spain. Because Spain did not officially recognize Mexican independence, delegates considered that trade treasonous to Mexico.[30]

Delegates ordered for the resolution to be printed in newspapers in the Mexican interior and in New Orleans.[30] It was not printed in Texas,[Note 3] which clearly indicates that it was intended to influence public opinion in the Mexican interior, rather than in Texas.[31] The resolution was not binding, and slaves continued to be imported to Texas through Cuba.[30]

Despite a vocal minority advocating for the unilateral implementation of the proposals, delegates agreed to present the requests to the Mexican Congress for approval but agreed to take action if it appeared their demands would be ignored.[31] As their last act, delegates elected Austin, James Miller, and Erasmo Seguín to deliver their petitions to Mexico City. Seguin, a prominent citizen of San Antonio de Béxar, had not attended the convention. Delegates hoped that Austin could persuade Seguin to accompany him, which would imply that Tejanos supported the resolutions.[31]

Preparations for delivery

When the convention adjourned on April 13, Austin went directly to San Antonio de Béxar to meet with Seguin.[31] Seguin called a series of meetings, held from May 3 to 5, for prominent locals to discuss the convention proceedings. He was the only Béxar resident who fully supported separate statehood.[32] Other residents suggested that the capital of Coahuila y Tejas should be moved to San Antonio de Béxar, which would give Texas more power. There was precedent for that since under Veramendi, the capital had just been moved from Saltillo to Monclova. If the legislature rejected the move, those residents vowed to support separate statehood.[33]

The third group of residents believed that the convention, like its predecessor, was illegal. Under their interpretation of the laws, only the state legislature could petition the Mexican Congress for such a drastic change.[33] Austin argued that the laws meant that no one could petition on behalf of the people unless the people had been consulted, and the convention served as that consultation. The meetings ended with no agreement on how to proceed.[34] Astin wrote that "the people here agree in substance with the rest of Texas, but differ as to the manner, and will express no opinion for, nor against."[35]

Seguin declined to accompany Austin. Miller also withdrew.[33] Texas was in the throes of a cholera epidemic, and Miller, a physician, felt that it his duty to stay and tend the sick.[36] Austin then visited Goliad but was unable to attract any more Tejano support.[37] He chose to go to Mexico City alone; he had visited several times and had established a good reputation among government officials. Although he was warned that his reception would likely be poor, he ignored suggestions to delay his journey.[36]

Reception

Within the Mexican interior, rumors abounded that Texas was on the verge of revolution. Many citizens in Matamoros believed that Texians had already declared independence and were raising an army. Santa Anna was infuriated, especially at the involvement of Houston, a former officer in the United States military.[36]

Immediately after Santa Anna had taken office in April, he had handed over all decision-making authority to his vice president, Valentín Gómez Farías, and retired to the countryside. Farías enacted many federalist reforms, which angered citizens and army leaders.[38] Much of the country was clamoring for a return to centralism, yet Texians wanted to take further steps toward self-rule.[39] When Austin arrived in Mexico City on July 18, several Mexican states had engaged in minor revolts against Farías's reforms. Although Texians had expelled troops within their province before Santa Anna and Farías took office, many officials identified the province with the other rebellious states and were suspicious of Austin's intentions.[39]

The cholera epidemic reached Mexico City within days of Austin's arrival, prompting Congress to adjourn before Austin could present the convention's resolutions. As he waited for the legislature to reconvene, Austin heard rumors that Texians were planning a third convention to unilaterally declare themselves a separate state.[39] Although Austin was also frustrated at the lack of progress, he disapproved of that drastic proposal. In an attempt to quell the more radical groups in Texas, Austin in October sent a letter to the ayuntamiento in San Antonio de Béxar in which he proposed that all of the ayuntamientos should jointly form a new state government.[40] In what could be interpreted as an inflammatory gesture, Austin signed his letter "dios y Tejas" ("God and Texas"), rather than the traditional Mexican closing "dios y libertad" ("God and liberty").[41] A few days after he had posted the letter, the immigration ban was repealed, assuaging one of the major Texian concerns.[40]

Austin had expected the letter to reach his friend Músquiz, who could be trusted to determine when or if it was appropriate to publicly disclose its contents. The letter arrived while Músquiz was out of town and was read by an unsympathetic ayuntamiento member.[42] At thar member's request, the ayuntamiento of San Antonio de Béxar forwarded the letter to state officials in Coahuila.[43] The new governor,[Note 4] Francisco Vidaurri y Villaseñor, ordered Austin's arrest.[44] Austin was arrested in December on suspicion of treason.[43] He was imprisoned in all of 1834 and remained in Mexico City on bond until July 1835.[34]

During Austin's imprisonment, the government addressed several more of the convention's proposals. At Santa Anna's urging, the Coahuila y Tejas legislature enacted several measures to placate the Texians. In early 1834, Texas gained an additional seat in the state legislature.[45] An American immigrant was named state Attorney General, and for the first time, foreigners were granted explicit permission to participate in retail trade.[46] Several American legal concepts, including trial by jury, were introduced to Texas, and English was authorized as a second language.[45] Finally, the state created four new municipalities in Texas: Matagorda, San Augustine, Bastrop, and San Patricio.[46] In a letter to a friend, Austin wrote, "Every evil complained of has been remedied. This fully compensates me for all I have suffered."[1]

See also

- Timeline of the Texas Revolution

Notes

- San Felipe de Austin was the capital of the first colony founded by Stephen F. Austin.

- Although Mexican law mandated that settlers convert to Catholicism, most Texians continued to practice their former religions with little interference from governmental authorities.

- Although Davis clearly asserts that the resolution was not printed within Texas, Barker (Oct 1902, p. 151) claims thst it was published in the Texas Advocate. Barker does not specify where that newspaper was printed or by whom.

- Veramendi died during the cholera epidemic.

References

- quoted in Davis (2006), p. 117.

- Manchaca (2001), pp. 164, 187.

- Ericson (2000), p. 33.

- Henson (1982), pp. 47–8.

- Morton (1943), p. 33.

- Davis (2006), p. 77.

- Davis (2006), p. 85.

- Henson (1982), pp. 95–102, 109.

- Davis (2006), p. 86.

- Davis (2006), p. 92.

- Davis (2006), p. 91.

- Barker (1985), p. 351.

- Davis (2006), p. 94.

- Steen, Ralph W., "Convention of 1832", Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Davis (2006), p. 95.

- Barker (January 1943), p. 330.

- Steen, Ralph W., "Convention of 1833", Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, retrieved December 17, 2009

- Davis (2006), p. 96.

- quoted in Davis (2006), p. 97.

- Davis (2006), p. 97.

- Miller (Jan 1988), p. 310.

- Miller (Jan 1988), p. 309.

- Davis (2006), p. 98.

- Ericson (Apr 1959), p. 458.

- Ericson (April 1959), p. 459.

- quoted in Miller (Jan 1988), p. 310.

- Ericson (Apr 1959), p. 460.

- quoted in Barker (Oct 1902), p. 151.

- Barker (Oct 1902), p. 150.

- Barker (Oct 1902), p. 151.

- Davis (2006), p. 99.

- Barker (Jan 1943), p. 331.

- Davis (2006), p. 100.

- Barker (Jan 1943), p. 332.

- quoted in Davis (2006), p. 100.

- Davis (2006), p. 101.

- Cantrell (1999), p. 268.

- Davis (2006), pp. 107–108.

- Davis (2006), p. 109.

- Davis (2006), p. 110.

- Cantrell (1999), p. 271.

- Cantrell (1999), pp. 272–77.

- Davis (2006), p. 111.

- Cantrell (1999), p. 278.

- Davis (2006), p. 117.

- Cantrell (1999), p. 291.

Sources

- Barker, Eugene C. (October 1902), "The African Slave Trade in Texas", Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Texas State Historical Association, 6 (2): 145–158, retrieved December 17, 2009

- Barker, Eugene C. (January 1943), "Native Latin American Contribution to the Colonization and Independence of Texas", Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Texas State Historical Association, 46 (3): 317–335, retrieved December 17, 2009

- Barker, Eugene Campbell (1985), The Life of Stephen F. Austin, founder of Texas, 1793–1836, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-78421-X originally published 1926 by Lamar & Barton

- Cantrell, Gregg (1999), Stephen F. Austin: Empresario of Texas, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-09093-2

- Davis, William C. (2006), Lone Star Rising, College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 978-1-58544-532-5 originally published 2004 by New York: Free Press

- Ericson, J.E. (April 1959), "Origins of the Texas Bill of Rights", Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Texas State Historical Association, 62 (4): 457–466

- Ericson, Joe E. (2000), The Nacogdoches story: an informal history, Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, ISBN 978-0-7884-1657-6

- Henson, Margaret Swett (1982), Juan Davis Bradburn: A Reappraisal of the Mexican Commander of Anahuac, College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 978-0-89096-135-3

- Manchaca, Martha (2001), Recovering History, Constructing Race: The Indian, Black, and White Roots of Mexican Americans, The Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Series in Latin American and Latino Art and Culture, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-75253-9

- Miller, Howard (January 1988), "Stephen F. Austin and the Anglo-Texan Response to the Religious Establishment in Mexico, 1821–1836", Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Texas State Historical Association, 91 (3): 283–316, retrieved December 17, 2009

- Morton, Ohland (July 1943), "Life of General Don Manuel de Mier y Teran", Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Texas State Historical Association, 47 (1), retrieved 2009-01-29

External links

- Convention of 1833 from the Handbook of Texas Online