Crown lengthening

Crown lengthening is a surgical procedure performed by a dentist, or more frequently a specialist periodontist. There are a number of reasons for considering crown lengthening in a treatment plan. Commonly, the procedure is used to expose a greater amount of tooth structure for the purpose of subsequently restoring the tooth prosthetically.[1] However, other indications include accessing subgingival caries, accessing perforations and to treat aesthetic disproportions such as a gummy smile. There are a number of procedures used to achieve an increase in crown length.[2]

| Crown lengthening | |

|---|---|

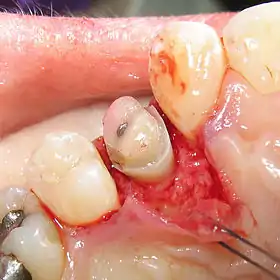

A palatal view of a maxillary premolar during a crown lengthening procedure. | |

| MeSH | D016556 |

Biomechanical considerations

Biologic width

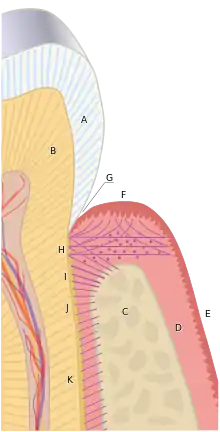

Biologic width is the distance established by "the junctional epithelium and connective tissue attachment to the root surface" of a tooth. The concept was first published by Ingber JS, Rose LF and Coslet JG. - The "Biologic Width"—A Concept in Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry in 1977 in the Alpha Omegan. It was based on cadaver measurements by Gargiulo, Wentz and Orban who didn’t use the term “Biologic Width” or attach any clinical relevance to the measurements in their 1961 article. The actual name, Biologic Width, came in 1962 from Dr. D. Walter Cohen at the University of Pennsylvania.[1] A In other words, it is the height between the deepest point of the gingival sulcus and the alveolar bone crest. This distance is important to consider when fabricating dental restorations, because they must respect the natural architecture of the gingival attachment if harmful consequences are to be avoided. The biologic width is patient specific and may vary anywhere from 0.75-4.3 mm.[3]

Based on the 1961 paper by Gargiulo, the mean biologic width was determined to be 2.04 mm, of which 1.07 mm is occupied by the connective tissue attachment and another approximate 0.97 mm is occupied by the junctional epithelium.[1][4] Because it is impossible to perfectly restore a tooth to the precise coronal edge of the junctional epithelium, it is often recommended to remove enough bone to have 3mm between the restorative margin and the crest of alveolar bone.[5][6][7] When restorations do not take these considerations into account and violate biologic width, three things tend to occur:[3]

- chronic pain

- chronic inflammation of the gingiva

- unpredictable loss of alveolar bone

Ferrule effect

In addition to crown lengthening to establish a proper biologic width, a 2mm height of tooth structure should be available to allow for a ferrule effect.[8] A ferrule, in respect to teeth, is a band that encircles the external dimension of residual tooth structure, not unlike the metal bands that exist around a barrel. Sufficient vertical height of tooth structure that will be grasped by the future crown is necessary to allow for a ferrule effect of the future prosthetic crown; it has been shown to significantly reduce the incidence of fracture in the endodontically treated tooth.[9] Because beveled tooth structure is not parallel to the vertical axis of the tooth, it does not properly contribute to ferrule height; thus, a desire to bevel the crown margin by 1 mm would require an additional 1 mm of bone removal in the crown lengthening procedure.[10] Frequently, however, restorations are performed without such a bevel.

Some recent studies suggest that, while ferrule is certainly desirable, it should not be provided at the expense of the remaining tooth/root structure.[11] On the other hand, it has also been shown that the "difference between an effective, long-term restoration and a failure can be as small as 1 mm of additional tooth structure that, when encased by a ferrule, provides great protection. When such a long-lasting, functional restoration cannot be predictably created, tooth extraction should be considered."[12]

Crown-to-root ratio

The alveolar bone surrounding one tooth will naturally surround an adjacent tooth, and removing bone for a crown lengthening procedure will effectively damage the bony support of adjacent teeth to some inevitable extent, as well as unfavorably increase the crown-to-root ratio. Additionally, once bone is removed, it is almost impossible to regain it to previous levels, and in case a patient would like to have an implant placed in the future, there might not be enough bone in the region once a crown lengthening procedure has been completed. Thus, it would be prudent for patients to thoroughly discuss all of their treatment planning options with their dentist before undergoing an irreversible procedure such as crown lengthening.

Treatment planning

Crown lengthening is often done in conjunction with a few other expensive and time-consuming procedures of which the combined goal is to improve the prosthetic forecast of a tooth. If a tooth, because of its relative lack of solid tooth structure, also requires a post and core, and thus, endodontic treatment, the total combined time, effort, and cost of the various procedures, as well as the impaired prognosis due to the combined inherent failure rates of each procedure, might combine to make it reasonable to have the tooth extracted. If the patient and the extraction site make for eligible candidates, it might be possible to have an implant placed and restored with more esthetic, timely, inexpensive, and reliable results. It is important to consider the many options available during the treatment planning stages of dental care.

An alternative to surgical crown lengthening is orthodontic forced eruption, it is non-invasive, does not remove or damage the bone and can be cost effective. The tooth is extruded a couple of millimeters with simple bracketing of adjacent teeth and using light forces this will only take a couple of months. A fiberotomy is performed after crown lengthening and is easily performed by the general dentist. In many cases such as this one shown, surgery and extraction may be avoided if patient is treated orthodontically rather than periodontally.

Crown lengthening techniques

Apically repositioned flap with osseous recontouring (resection)[13]

An apically repositioned flap is a widely used procedure that involves flap elevation with subsequent osseous contouring. The flap is designed such that it is replaced more apical to its original position and thus immediate exposure of sound tooth structure is gained. As discussed above, when planning a crown lengthening procedure consideration must be given to maintenance of the biologic width.

As a general rule, at least 4 mm of sound tooth structure must be exposed at the time of surgery. This, therefore, allows for proliferation of the supracrestal soft tissues, which are estimated to cover 2– 3 mm of the coronal root structure thereby leaving 1–2 mm of supragingivally located sound tooth structure. Furthermore, thought has to be given to the inherent tendency of gingival tissues to bridge abrupt changes in the contour of the bone crest. As such it is advised that bone recontouring must be performed not only around the problem tooth but also at the adjacent teeth to gradually reduce the osseous profile.

Consequently, substantial amounts of attachment may have to be sacrificed when crown lengthening is accomplished with an apically positioned flap technique. It is also important to remember that, for esthetic reasons, symmetry of tooth length must be maintained between the right and left sides of the dental arch. This may, in some situations, call for the inclusion of even more teeth in the surgical procedure.[14]

Indications

Crown lengthening of multiple teeth in a quadrant or sextant of the dentition

Contraindications

Single teeth in the aesthetic zone becomes increasingly destructive.

Technique[13]

- A reverse bevel incision is made using a scalpel. This initial incision is guided by pre-operative planning and is based on the amount of tooth structure to be exposed. The beveling incision also should follow a scalloped outline, to ensure maximal interproximal coverage of the alveolar bone when the flap subsequently is repositioned. Vertical releasing incisions extending out into the alveolar mucosa, past the mucogingival junction, are made at each of the end points of the reverse incision, thereby making apical repositioning of the flap possible.

- A full‐thickness mucoperiosteal flap is then raised to expose the root surfaces. The flap, incorporating the buccal/ lingual gingiva and alveolar mucosa, then has to be elevated beyond the mucogingival line in order to be able later to reposition the soft tissue apically. The marginal collar of tissue is then removed with curettes.

- Osseous recontouring is then performed using a rotating round bur and copious water spray or bone chisels. The recontouring should aim to re-create the normal form of the alveolar crest, but at a more apical level.

- Following the osseous surgery, the flap is repositioned to the level of the newly recontoured alveolar bone crest and secured in position. Full soft tissue coverage is inherently more difficult and as such a periodontal dressing should be applied to protect the denuded interproximal alveolar bone to retain the soft tissue at the level of the bone crest.

Advantages

Immediate increase in sound tooth structure can be achieved.

Disadvantages

Difficult procedure for patients to tolerate, increased post-operative pain [14]

Forced tooth eruption[13]

Orthodontic tooth movement can be used to erupt teeth in adults. If moderate eruptive forces are applied, the entire eruptive apparatus will move in unison with the tooth. As such, the units required must be extruded a distance equal to or slightly longer than the portion of sound tooth structure that will be exposed in the following surgical treatment. Once stabilized, a full-thickness flap is then elevated and osseous recontouring is performed to expose the required tooth structure. To restore aesthetic proportions correctly, the hard and soft tissues of adjacent teeth should remain unchanged.

Indications

Forced tooth eruption is indicated where crown lengthening is required, but attachment and bone from adjacent teeth must be preserved.

Contraindications

Forced tooth eruption requires a fixed orthodontic appliance. This poses problems in patients with reduced dentitions; in such instances alternative crown lengthening procedures must be considered

Technique[13]

Orthodontic brackets are bonded to the teeth requiring crown lengthening surgery and then to adjacent teeth, these are then combined within an archwire. A power elastic band is then tied from the bracket to the archwire (or the bar), which pulls the tooth coronally. The direction of the tooth movement must be carefully checked to ensure no tilting or movement of adjacent teeth occurs.

Forced tooth eruption can also be performed with fiberotomy. This technique is adopted when gingival margins and crystal bone height are to be maintained at their pretreatment locations. Fiberotomy is performed at 7-10 day intervals during treatment. A scalpel is used to sever supracrestal connective tissue fibres, thereby preventing crystal bone from following the root in a coronal direction.

Advantages

Preserves osseous structure around adjacent teeth

Disadvantages

Procedure requires fixed wire placement. Treatment time can be prolonged.

References

- Ingber, Jeffrey; Rose, LF; Coslet, JG (1977). "The Biologic Width - A concept in periodontics and restorative dentistry". Alpha Omegan. 70 (3): 62–65. PMID 276259.

- Al-Harbi F, Ahmad I (February 2018). "A guide to minimally invasive crown lengthening and tooth preparation for rehabilitating pink and white aesthetics". British Dental Journal. 224 (4): 228–234. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.121. PMID 29472662. S2CID 3496543.

- "A Comprehensive Guide To Biologic Width". speareducation.com. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- Gargiulo AW, Wentz FM, Orban B (July 1961). "Dimensions and relations of the dentogingival junction in humans". The Journal of Periodontology. 32 (3): 261–7. doi:10.1902/jop.1961.32.3.261.

- Nevins M, Skurow HM (1984). "The intracrevicular restorative margin, the biologic width, and the maintenance of the gingival margin". Int J Perio Rest D. 3 (3): 31–49. PMID 6381360.

- Brägger U, Lauchenauer D, Lang NP (January 1992). "Surgical lengthening of the clinical crown". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 19 (1): 58–63. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb01150.x. PMID 1732311.

- Padbury A, Eber R, Wang HL (May 2003). "Interactions between the gingiva and the margin of restorations". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 30 (5): 379–85. doi:10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.01277.x. PMID 12716328.

- Galen WW, Mueller KI: Restoration of the Endodontically Treated Tooth. In Cohen, S. Burns, RC, editors: Pathways of the Pulp, 8th Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, Inc. 2002. page 784.

- Barkhordar RA, Radke R, Abbasi J (June 1989). "Effect of metal collars on resistance of endodontically treated teeth to root fracture". The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 61 (6): 676–8. doi:10.1016/s0022-3913(89)80040-x. PMID 2657023.

- DiPede L (2004). Fixed prosthodontic lecture series notes (Report). New Jersey Dental School.

- Stankiewicz NR, Wilson PR (July 2002). "The ferrule effect: a literature review". International Endodontic Journal. 35 (7): 575–81. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00557.x. PMID 12190896.

- Wagnild GW, Mueller KI (1994). "The restoration of the endodontically treated tooth.". Pathways of the pulp (6th ed.). St Louis: Mosby-Year Book. pp. 604–31.

- Lindhe J, Lang N (2015). Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 9780470672488.

- Karimbux N (2011). Clinical Cases in Periodontics. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. ISBN 9780813807942.