Cypriot Greek

Cypriot Greek (Greek: κυπριακή ελληνική locally [cipriaˈci elːiniˈci] or κυπριακά [cipriaˈka]) is the variety of Modern Greek that is spoken by the majority of the Cypriot populace and Greek Cypriot diaspora. It is considered a divergent dialect as it differs from Standard Modern Greek[note 2] in various aspects of its lexicon,[2] phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax and even pragmatics,[3] not only for historical reasons, but also because of geographical isolation, different settlement patterns, and extensive contact with typologically distinct languages.[4]

| Cypriot Greek | |

|---|---|

| κυπριακή ελληνική κυπριακά | |

| Pronunciation | [cipriaˈci elːiniˈci] [cipriaˈka] |

| Native to | Cyprus |

Native speakers | c. 700,000 in Cyprus (2011)[1][note 1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Greek alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | cypr1249 |

| Linguasphere | 56-AAA-ahg |

Classification

Cypriot Greek is not an evolution of ancient Arcadocypriot Greek, but derives from Byzantine Medieval Greek.[5] It has traditionally been placed in the southeastern group of Modern Greek varieties, along with the dialects of the Dodecanese and Chios (with which it shares several phonological phenomena).

Though Cypriot Greek tends to be regarded as a dialect by its speakers, it is unintelligible to speakers of Standard Modern Greek without adequate prior exposure.[6] Greek-speaking Cypriots are diglossic in the vernacular Cypriot Greek (the "low" variety) and Standard Modern Greek (the "high" variety).[7][8] Cypriot Greek is itself a dialect continuum with an emerging koine.[9] Davy, Ioannou & Panayotou (1996) have argued that diglossia has given way to a "post-diglossic [dialectal] continuum [...] a quasi-continuous spread of overlapping varieties".[10]

History

Cyprus was cut off from the rest of the Greek-speaking world from the 7th to the 10th century AD due to Arab attacks. It was reintegrated in the Byzantine Empire in 962 to be isolated again in 1191 when it fell to the hands of the Crusaders. These periods of isolation led to the development of various linguistic characteristics distinct from Byzantine Greek.

The oldest surviving written works in Cypriot date back to the Medieval period. Some of these are: the legal code of the Kingdom of Cyprus, the Assizes of Jerusalem; the chronicles of Leontios Machairas and Georgios Voustronios; and a collection of sonnets in the manner of Francesco Petrarca. In the past hundred years, the dialect has been used in poetry (with major poets being Vasilis Michaelides and Dimitris Lipertis). It is also traditionally used in folk songs and τσιαττιστά (tsiattistá, battle poetry, a form of playing the Dozens) and the tradition of ποιητάρηες (poiitáries, bards).

Cypriot Greek had been historically used by some members of the Turkish Cypriot community, especially after the end of Ottoman control and consequent British administration of the island. In 1960, it was reported that 38% of the Turkish Cypriots were able to speak Greek along with Cypriot Turkish. Some Turkish Cypriots of Nicosia and Paphos were also speaking Cypriot Greek as their mother tongue according to early 20th century population records.[11]

In the late 1970s, Minister of Education Chrysostomos A. Sofianos upgraded the status of Cypriot by introducing it in education. More recently, it has been used in music, e.g. in reggae by Hadji Mike and in rap by several Cypriot hip hop groups, such as Dimiourgoi Neas Antilipsis (DNA). Locally produced television shows, usually comedies or soap operas, make use of the dialect, for example with Vourate Geitonoi (βουράτε instead of τρέξτε) or Oi Takkoi (Τάκκος being a uniquely Cypriot name). The 2006 feature film Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest features actor Jimmy Roussounis arguing in Cypriot with another crew member speaking Gibrizlidja (Cypriot Turkish) about a captain's hat they find in the sea. Peter Polycarpou routinely spoke in Cypriot in his role as Chris Theodopolopoudos in the British television comedy series Birds of a Feather. In a July 2014 episode of the American TV series The Leftovers, Alex Malaos's character uses the dialect saying "Εκατάλαβα σε" ('I understood'). In the American mockumentary comedy horror television series What We Do in the Shadows, actress Natasia Demetriou, as the vampiric character Nadja, occasionally exclaims phrases in Cypriot.

Today, Cypriot Greek is the only variety of Modern Greek with a significant presence of spontaneous use online, including blogs and internet forums, and there exists a variant of Greeklish that reflects its distinct phonology.

Phonology

Studies of the phonology of Cypriot Greek are few and tend to examine very specific phenomena, e.g. gemination, "glide hardening". A general overview of the phonology of Cypriot Greek has only ever been attempted once, by Newton 1972, but parts of it are now contested.

Consonants

Cypriot Greek has geminate and palato-alveolar consonants, which Standard Modern Greek lacks, as well as a contrast between [ɾ] and [r], which Standard Modern Greek also lacks.[12] The table below, adapted from Arvaniti 2010, p. 4, depicts the consonantal inventory of Cypriot Greek.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | ||

| Nasal | m | mː | n | nː | |||||||||

| Stop | p | pʰː | t | tʰː | t͡s | t͡ʃ | t͡ʃʰː | c | cʰː | k | kʰː | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | fː | θ | θː | s | sː | ʃ | ʃː | x | xː | ||

| voiced | v | ð | z | ʒ | ʝ | ɣ | |||||||

| Lateral | l | lː | |||||||||||

| Rhotic | ɾ | r | |||||||||||

Stops /p t c k/ and affricate /t͡ʃ/ are unaspirated and may be pronounced weakly voiced in fast speech.[13] /pʰː tʰː cʰː kʰː/ are always heavily aspirated and they are never preceded by nasals,[14] with the exception of some loans, e.g. /ʃamˈpʰːu/ "shampoo".[15] /t͡ʃ/ and /t͡ʃʰː/ are laminal post-alveolars.[16] /t͡s/ is pronounced similarly to /t͡ʃʰː/, in terms of closure duration and aspiration.[16]

Voiced fricatives /v ð ɣ/ are often pronounced as approximants and they are regularly elided when intervocalic.[13] /ʝ/ is similarly often realised as an approximant [j] in weak positions.[17]

The palatal lateral approximant [ʎ] is most often realised as a singleton or geminate lateral [ʎ(ː)] or a singleton or geminate fricative [ʝ(ː)], and sometimes as a glide [j] (cf. yeísmo).[18] The circumstances under which all the different variants surface are not very well understood, but [ʝ(ː)] appear to be favoured in stressed syllables and word-finally, and before /a e/.[19] Pappas 2009 identifies the following phonological and non-phonological influencing factors: stress, preceding vowel, following vowel, position inside word; and sex, education, region, and time spent living in Greece (where [ʎ] is standard).[19] Arvaniti 2010 notes that speakers of some local varieties, notably that of Larnaca, "substitute" the geminate fricative for /ʎ/,[20] but Pappas 2009 contests this, saying that, "[ʝ(ː)] is robustly present in the three urban areas of Lefkosia, Lemesos and Larnaka as well as the rural Kokinohoria region, especially among teenaged speakers ... the innovative pronunciation [ʝ(ː)] is not a feature of any local patois, but rather a supra-local feature."[21]

The palatal nasal [ɲ] is produced somewhat longer than other singleton nasals, though not as long as geminates. /z/ is similarly "rather long".[13]

The alveolar trill /r/ is the geminate counterpart of the tap /ɾ/.[16]

Palatalisation and glide hardening

In analyses that posit a phonemic (but not phonetic) glide /j/, palatals and postalveolars arise from CJV (consonant–glide–vowel) clusters, namely:[22]

- /mjV/ → [mɲV]

- /njV/ → [ɲːV]

- /ljV/ → [ʎːV] or [ʝːV]

- /kjV/ → [t͡ʃV] or [cV]

- /xjV/ → [ʃV] or [çV]

- /ɣjV/ → [ʝV]

- /zjV/ → [ʒːV]

- /t͡sjV/ → [t͡ʃʰːV]

The glide is not assimilated, but hardens to an obstruent [c] after /p t f v θ ð/ and to [k] after /ɾ/.[22] At any rate, velar stops and fricatives are in complementary distribution with palatals and postalveolars before front vowels /e i/;[16] that is to say, broadly, /k kʰː/ are palatalised to either [c cʰː] or [t͡ʃ t͡ʃʰː]; /x xː/ to [ç çː] or [ʃ ʃː]; and /ɣ/ to [ʝ].

Geminates

There is considerable disagreement on how to classify Cypriot Greek geminates, though they are now generally understood to be "geminates proper" (rather than clusters of identical phonemes or "fortis" consonants).[23] Geminates are 1.5 to 2 times longer than singletons, depending, primarily, on position and stress.[24] Geminates occur both word-initially and word-medially. Word-initial geminates tend to be somewhat longer.[25] Tserdanelis & Arvaniti 2001 have found that "for stops, in particular, this lengthening affects both closure duration and VOT",[26] but Davy & Panayotou 2003 claim that stops contrast only in aspiration, and not duration.[27] Armosti 2010 undertook a perceptual study with thirty native speakers of Cypriot Greek,[28] and has found that both closure duration and (the duration and properties of) aspiration provide important cues in distinguishing between the two kinds of stops, but aspiration is slightly more significant.[29]

Assimilatory processes

Word-final /n/ assimilates with succeeding consonants—other than stops and affricates—at word boundaries producing post-lexical geminates.[30] Consequently, geminate voiced fricatives, though generally not phonemic, do occur as allophones. Below are some examples of geminates to arise from sandhi.

- /ton ˈluka/ → [to‿ˈlˑuka] τον Λούκα "Lucas" (acc.)

- /en ˈða/ → [e‿ˈðːa] εν δα "[s/he] is here"

- /pu tin ˈɾiza/ → [pu ti‿ˈriza] που την ρίζα "from the root"

In contrast, singleton stops and affricates do not undergo gemination, but become fully voiced when preceded by a nasal, with the nasal becoming homorganic.[13] This process is not restricted to terminal nasals; singleton stops and affricates always become voiced following a nasal.[31]

- /kaˈpnizumen ˈpuɾa/ → [kaˈpnizumem‿ˈbuɾa] καπνίζουμεν πούρα "[we] smoke cigars"

- /an ˈt͡ʃe/ → [an‿ˈd͡ʒe] αν τζ̌αι "even though"

- /tin ciɾi.aˈcin/ → [tiɲ‿ɟirĭ.aˈcin] την Κυριακήν "on Sunday"

Word-final /n/ is altogether elided before geminate stops and consonant clusters:[32]

- /eˈpiasamen ˈfcoɾa/ → [eˈpcasame‿ˈfcoɾa] επιάσαμεν φκιόρα "[we] bought flowers"

- /ˈpa‿stin cʰːeˈlːe/ → [ˈpa‿sti‿cʰːeˈlːe] πα' στην κκελλέ "on the head"

Like with /n/, word-final /s/ assimilates to following [s] and [ʃ] producing geminates:[33]

- /as ʃoˈnisi/ → [a‿ʃːoˈnisi] ας σ̌ονίσει "let it snow"

Lastly, word-final /s/ becomes voiced when followed by a voiced consonant belonging to the same phrase, like in Standard Greek:[32]

- /tis ˈmaltas/ → [tiz‿ˈmaltas] της Μάλτας "of Malta"

- /aˈɣonas ˈðromu/ → [aˈɣonaz‿ˈðromu] αγώνας δρόμου "race"

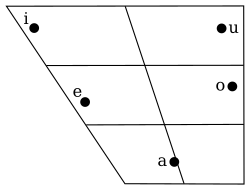

Vowels

Cypriot Greek has a five-vowel system /i, u, e, o, a/[34] [35] that is nearly identical to that of Standard Modern Greek.[note 3]

Close vowels /i u/ following /t/ at the end of an utterance are regularly reduced (50% of all cases presented in study) to "fricated vowels" (40% of all cases, cf. Slavic yers), and are sometimes elided altogether (5% of all cases).[36]

In glide-less analyses, /i/ may alternate with [k] or [c],[37] e.g. [kluvi] "cage" → [klufca] "cages", or [kulːuɾi] "koulouri" → [kulːuɾ̥ka] "koulouria"; and, like in Standard Modern Greek, it is pronounced [ɲ] when found between /m/ and another vowel that belongs to the same syllable,[31] e.g. [mɲa] "one" (f.).

Stress

Cypriot Greek has "dynamic" stress.[32] Both consonants and vowels are longer in stressed than in unstressed syllables, and the effect is stronger word-initially.[38] There is only one stress per word, and it can fall on any of the last four syllables. Stress on the fourth syllable from the end of a word is rare and normally limited to certain verb forms. Because of this possibility, however, when words with antepenultimate stress are followed by an enclitic in Cypriot Greek, no extra stress is added (unlike Standard Modern Greek, where the stress can only fall on one of the last three syllables),[32] e.g. Cypriot Greek το ποδήλατον μου [to poˈðilato‿mːu], Standard Modern Greek το ποδήλατό μου [to poˌðilaˈto‿mu] "my bicycle".

Grammar

An overview of syntactic and morphological differences between Standard Modern Greek and Cypriot Greek can be found in Hadjioannou, Tsiplakou & Kappler 2011, pp. 568–9.

Vocabulary

More loanwords are in everyday use than in Standard Modern Greek.[2] These come from Old French, Italian, Occitan, Turkish and, increasingly, from English. There are also Arabic expressions (via Turkish) like μάσ̌σ̌αλλα [ˈmaʃːalːa] "mashallah" and ίσ̌σ̌αλλα [ˈiʃːalːa] "inshallah". Much of the Cypriot core vocabulary is different from the modern standard's, e.g. συντυχάννω [sindiˈxanːo] in addition to μιλώ "I talk", θωρώ [θοˈɾo] instead of βλέπω "I look", etc. A historically interesting example is the occasional use of archaic πόθεν instead of από πού for the interrogative "from where?" which makes its closest translation to the English "whence" which is also archaic in most of the English speaking world. Ethnologue reports that the lexical similarity between Cypriot Greek and Demotic Greek is in the range of 84–93%.[39]

Orthography

There is no established orthography for Cypriot Greek.[40][41] Efforts have been made to introduce diacritics to the Greek alphabet to represent palato-alveolar consonants found in Cypriot, but not in Standard Modern Greek, e.g. the combining caron ⟨ˇ⟩, by the authors of the "Syntychies" lexicographic database at the University of Cyprus.[42] When diacritics are not used, an epenthetic ⟨ι⟩—often accompanied by the systematic substitution of the preceding consonant letter—may be used to the same effect (as in Polish), e.g. Standard Modern Greek παντζάρι [paˈ(n)d͡zaɾi] → Cypriot Greek ππαντζιάρι [pʰːaˈnd͡ʒaɾi], Standard Modern Greek χέρι [ˈçeɾi] → Cypriot Greek σιέρι [ˈʃeɾi].

Geminates (and aspirates) are represented by two of the same letter, e.g. σήμμερα [ˈsimːeɾa] "today", though this may not be done in cases where the spelling would not coincide with Standard Modern Greek's, e.g. σήμμερα would still be spelt σήμερα.[note 4]

In computer-mediated communication, Cypriot Greek, like Standard Modern Greek, is commonly written in the Latin script,[43] and English spelling conventions may be adopted for shared sounds,[44] e.g. ⟨sh⟩ for /ʃ/ (and /ʃː/).

See also

- Languages of Cyprus

- Arcadocypriot Greek for the ancient Greek spoken on Cyprus

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- This number includes speakers of all Greek varieties in Cyprus.

- Standard Modern Greek is the variety based on Demotic (but with elements of Katharevousa) that became the official language of Greece in 1976. See also: Greek language question.

- For an acoustic comparison of the two vowel systems see Themistocleous 2017a and Themistocleous 2017b.

- Geminates are present in Cypriot Greek and were present (and distinct) in Ancient and earlier Koine, but they are not in Standard Modern Greek. Late twentieth-century spelling reforms in Greece were not indiscriminate, i.e. some words are still spelt with two consecutive consonant letters, but are not pronounced that way. In addition, Cypriot Greek has developed geminates in words where they were not previously found.

Citations

- "Statistical Service - Population Census 2011". www.mof.gov.cy.

- Ammon 2006, p. 1886.

- Themistocleous et al. 2012, p. 262.

- Ammon 2006, pp. 1886–1887.

- Joseph & Tserdanelis 2003, p. 823.

- Arvaniti 2006, p. 26.

- Arvaniti 2006, p. 25.

- Tsiplakou 2012.

- Arvaniti 2006, pp. 26–27.

- Davy, Ioannou & Panayotou 1996, pp. 131, 135.

- Türk dili (in Turkish). Türk Dil Kurumu. 2003.

- Arvaniti 2010, pp. 3–4.

- Arvaniti 1999, pp. 2–3.

- Arvaniti 1999, p. 2.

- Davy, Ioannou & Panayotou 1996, p. 134.

- Arvaniti 1999, p. 3.

- Arvaniti 2010, p. 11.

- Pappas 2009, p. 307.

- Pappas 2009, p. 309.

- Arvaniti 2010, pp. 10–11.

- Pappas 2009, p. 313.

- Nevins & Chirotan 2008, pp. 13–14.

- Arvaniti 2010, p. 12.

- Arvaniti 2010, pp. 4–5.

- Arvaniti 2010, p. 5.

- Tserdanelis & Arvaniti 2001, p. 35.

- Davy & Panayotou 2003, p. 8: "... there is no evidence for the assumption that CG /pʰ/ is distinctively long (or geminate). The CGasp system contains simply tense aspirated and lax unaspirated stops."

- Armosti 2010, pp. 37.

- Armosti 2010, pp. 52–53.

- Arvaniti 2010, p. 8.

- Arvaniti 1999, p. 4.

- Arvaniti 1999, p. 5.

- Armosti 2011, p. 97.

- Georgiou 2018, p. 70.

- Georgiou 2019, p. 4.

- Eftychiou 2007, p. 518.

- Arvaniti 2010, p. 1.

- Arvaniti 2010, pp. 17–18.

- Greek at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Arvaniti 1999, p. 1.

- Themistocleous 2010, p. 158.

- Themistocleous et al. 2012, pp. 263–264.

- Themistocleous 2010, pp. 158–159.

- Themistocleous 2010, p. 165.

Bibliography

- Ammon, Ulrich, ed. (2006). Sociolinguistics/Soziolinguistik 3: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society/Ein Internationales Handbuch Zur Wissenschaft Von Sprache und Gesellschaft (2 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110184181.

- Armosti, Spyros (11–14 June 2009). "The perception of plosive gemination in Cypriot Greek". On-line Proceedings of the 4th International Conference of Modern Greek Dialects and Linguistic Theory. Chios, Greece (published 2010). pp. 33–53.

- Armosti, Spyros (2011). "Fricative and sonorant super-geminates in Cypriot Greek: a perceptual study". Studies in Modern Greek Dialects and Linguistic Theory. Nicosia: Research Centre of Kykkos Monastery. pp. 97–112.

- Arvaniti, Amalia (1999). "Cypriot Greek". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 29 (2): 173–178. doi:10.1017/S002510030000654X. S2CID 163926812.

- Arvaniti, Amalia (2006). "Erasure as a means of maintaining diglossia in Cyprus". San Diego Linguistic Papers (2).

- Arvaniti, Amalia (2010). "A (brief) review of Cypriot Phonetics and Phonology" (PDF). The Greek Language in Cyprus from Antiquity to the Present Day. University of Athens. pp. 107–124. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-23.

- Davy, Jim; Ioannou, Yannis; Panayotou, Anna (1994). "French and English loans in Cypriot diglossia". Travaux de la Maison de l'Orient méditerranéen. Chypre hier et aujourd’hui entre Orient et Occident. Vol. 25. Nicosia, Cyprus: Université de Chypre et Université Lumière Lyon 2 (published 1996). pp. 127–136.

- Davy, Jim; Panayotou, Anna (8–21 September 2003). Phonological constraint on the phonetics of Cypriot Greek: does Cypriot Greek have geminate stops? (PDF). Proceedings of 6th International Conference of Greek Linguistics. Rethymno, Greece.

- Eftychiou, Eftychia (6–10 August 2007). "Stop-vowel coarticulation in Cypriot Greek" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Congress of Phonetic Sciences XVI. Saarbrücken, Germany. pp. 517–520.

- Georgiou, Georgios (2018). "Discrimination of L2 Greek vowel contrasts: Evidence from learners with Arabic L1 background". Speech Communication. 102: 68–77. doi:10.1016/j.specom.2018.07.003. S2CID 52297330.

- Georgiou, Georgios (2019). "Bit and beat are heard as the same: Mapping the vowel perceptual patterns of Greek-English bilingual children". Language Sciences. 72: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2018.12.001. S2CID 150229377.

- Grohmann, Kleanthes K.; Papadopoulou, Elena; Themistocleous, Charalambos (2017). "Acquiring Clitic Placement in Bilectal Settings: Interactions between Social Factors". Frontiers in Communication. 2 (5). doi:10.3389/fcomm.2017.00005.

- Hadjioannou, Xenia; Tsiplakou, Stavroula; Kappler, Matthias (2011). "Language policy and language planning in Cyprus". Current Issues in Language Planning. 12 (4): 503–569. doi:10.1080/14664208.2011.629113. hdl:10278/29371. S2CID 143966308.

- Joseph, Brian D. (2010). "Greek, Modern". In Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. pp. 464–467. ISBN 9780080877754.

- Joseph, Brian D.; Tserdanelis, Georgios (2003). "Modern Greek". In Roelcke, Thorsten (ed.). Variationstypologie. Ein sprachtypologisches Handbuch zu den europäischen Sprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart / Variation Typology. A Typological Handbook of European Languages. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 823–836.

- Nevins, Andrew Ira; Chirotan, Ioana (2008). "Phonological Representations and the Variable Patterning of Glides" (PDF). Lingua. 118 (12): 1979–1997. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2007.10.006.

- Newton, Brian (1972). Cypriot Greek: Its phonology and inflections. The Hague: Mouton.

- Pappas, Panayiotis (11–14 June 2009). "A new sociolinguistic variable in Cypriot Greek" (PDF). On-line Proceedings of the 4th International Conference of Modern Greek Dialects and Linguistic Theory. Chios, Greece. pp. 305–314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2013.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos; Tsiplakou, Stavroula (2013). "High Rising Terminals In Cypriot Greek: Charting `Urban' Intonation". In Auer, Peter; Reina, Javier Caro; Kaufmann, Göz (eds.). Language Variation - European Perspectives IV: Selected papers from the Sixth International Conference on Language Variation in Europe (ICLaVE 6), Freiburg, June 2011. Amsterdam: John Benjamin's. pp. 159–172.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos; Logotheti, Angeliki (2016). "Standard Modern Greek and Cypriot Greek vowels: a sociophonetic study". In Ralli, Angela; Koutsoukos, Nikos; Bompolas, Stavros (eds.). 6th International Conference on Modern Greek Dialects and Linguistic Theory (MGDLT6), September 25-28, 2014. University of Patras. pp. 177–183.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos (2014). "Edge-Tone Effects and Prosodic Domain Effects on Final Lengthening". Linguistic Variation. 14 (1): 129–160. doi:10.1075/lv.14.1.06the.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos (2016). "Seeking an Anchorage. Stability and Variability in Tonal Alignment of Rising Prenuclear Pitch Accents in Cypriot Greek". Language and Speech. 59 (4): 433–461. doi:10.1177/0023830915614602. PMID 28008803. S2CID 24397973.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos (2016). "The bursts of stops can convey dialectal information". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 140 (4): EL334–EL339. Bibcode:2016ASAJ..140L.334T. doi:10.1121/1.4964818. PMID 27794314.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos; Savva, Angelandria; Aristodemou, Andrie (2016). "Effects of stress on fricatives: Evidence from Standard Modern Greek". Interspeech 2016. pp. 1–4.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos (2017a). "Dialect classification using vowel acoustic parameters". Speech Communication. 92: 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.specom.2017.05.003.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos (2017b). "The Nature of Phonetic Gradience across a Dialect Continuum: Evidence from Modern Greek Vowels". Phonetica. 74 (3): 157–172. doi:10.1159/000450554. PMID 28268213. S2CID 7596117.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos; Katsoyannou, Marianna; Armosti, Spyros; Christodoulou, Kyriaci (7–11 August 2012). Cypriot Greek Lexicography: A Reverse Dictionary of Cypriot Greek (PDF). 15th European Association for Lexicography (EURALEX) Conference. Oslo, Norway. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Themistocleous, Christiana (2010). "Writing in a non-standard Greek variety: Romanized Cypriot Greek in online chat". Writing Systems Research. 2. 2 (2): 155–168. doi:10.1093/wsr/wsq008.

- Tserdanelis, Giorgos; Arvaniti, Amalia (2001). "The acoustic characteristics of geminate consonants in Cypriot Greek" (PDF). Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Greek Linguistics. Thessaloniki, Greece: University Studio Press. pp. 29–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- Tsiplakou, Stravoula (21–24 August 2012). Charting Nicosian: properties and perceptions of an emergent urban dialect variety. Sociolinguistics Symposium 19. Berlin, Germany.

Further reading

- Armosti, Spyros (6–10 August 2007). The perception of Cypriot Greek 'super-geminates' (PDF). Proceedings of the International Congress of Phonetic Sciences XVI. Saarbrücken, Germany. pp. 761–764.

- Armosti, Spyros (1–4 September 2011). "An articulatory study of word-initial stop gemination in Cypriot Greek". Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of Greek Linguistics (PDF). Komotini, Greece (published 2012). pp. 122–133.

- Arvaniti, Amalia (1998). "Phrase accents revisited: comparative evidence from Standard and Cypriot Greek". Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing (PDF). Vol. 7. Sydney. pp. 2883–2886. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- Arvaniti, Amalia (2001). "Comparing the phonetics of single and geminate consonants in Cypriot and Standard Greek.". Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Greek Linguistics (PDF). Thessaloniki, Greece: University Studio Press. pp. 37–44.

- Eklund, Robert (2008). "Pulmonic ingressive phonation: Diachronic and synchronic characteristics, distribution and function in animal and human sound production and in human speech". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 38 (3): 235–324. doi:10.1017/S0025100308003563. S2CID 146616135.

- Gil, David (2011). "Para-Linguistic Usages of Clicks". In Dryer, Matthew S.; Haspelmath, Martin (eds.). The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Munich: Max Planck Digital Library.

- Petinou, Kakia; Okalidou, Areti (2006). "Speech patterns in Cypriot-Greek late talkers". Applied Psycholinguistics. 27 (3): 335–353. doi:10.1017/S0142716406060309. S2CID 145326236.

- Payne, Elinor; Eftychiou, Eftychia (2006). "Prosodic shaping of consonant gemination in Cypriot Greek". Phonetica. 63 (2–3): 175–198. doi:10.1159/000095307. PMID 17028461. S2CID 26027083.

- Rowe, Charley; Grohmann, Kleanthes K. (November 2013). "Discrete bilectalism: towards co-overt prestige and diglossic shift in Cyprus". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2013 (224): 119–142. doi:10.1515/ijsl-2013-0058. S2CID 144677707.

- Bernardi, Jean-Philippe; Themistocleous, Charalambos (2017). "Modelling prosodic structure using Artificial Neural Networks". Experimental Linguistics 2017: 17–20. arXiv:1706.03952.

- Botinis, Antonis; Christofi, Marios; Themistocleous, Charalambos; Kyprianou, Aggeliki (2004). "Duration correlates of stop consonants in Cypriot Greek". In Branderud, Peter; Engstrand, Olle; Traunmüller, Hartmut (eds.). FONETIK 2004. Stockholm: Dept. of Linguistics, Stockholm University. pp. 140–143.

- Melissaropoulou, Dimitra; Themistocleous, Charalambos; Tsiplakou, Stavroula; Tsolakidis, Symeon (2013). "The Present Perfect in Cypriot Greek revisited". In Auer, Peter; Reina, Javier Caro; Kaufmann, Göz (eds.). Language Variation -- European Perspectives IV. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamin's.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos (2011). Prosody and Information Structure in Greek (Prosodia kai plirophoriaki domi stin Ellinici) (Ph.D.).

- Themistocleous, Charalambos (2014). "Modern Greek Prosody. Using speech melody in communication (Prosodia tis Neas Ellinikis. I axiopoiisi tis melodias tis fonis stin epikoinonia)". Stasinos. 6: 319–344.

- Themistocleous, Charalambos (2011). "Nuclear Accents in Athenian and Cypriot Greek (ta pirinika tonika ipsi tis kipriakis ellinikis)". In Gavriilidou, Zoe; Efthymiou, Angeliki; Thomadaki, Evangelia; Kambakis-Vougiouklis, Penelope (eds.). 10th International Conference of Greek Linguistics. Democritus University of Thrace. pp. 796–805.